Trauma, addiction, and regret can feel like life sentences, and We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is a rare celebrity book that shows how a flawed human being quietly commutes his own.

The central idea of We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is that you can’t rewrite the past, but you can refuse to let shame run the rest of your life, and that stubborn decision quietly re-organises everything from work to love.

If you’ve ever replayed old mistakes at 3 a.m., the memoir feels like an eighty-seven-year-old sitting beside you at the kitchen table, confessing his worst moments and then saying, almost shyly, that he somehow survived.

In that sense, *We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir * is less a victory lap than an instruction manual for living with the parts of yourself you’d rather disown.

That claim isn’t airy self-help: Hopkins anchors his story in hard numbers – nearly fifty years of sobriety since joining Alcoholics Anonymous in 1975, two Academy Awards for The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and The Father (2020), and a career that spans more than ninety film and television roles, with Guinness noting that his Silence performance is the shortest ever to win Best Actor and that his 2021 win made him the oldest acting Oscar winner.

We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is best for readers who want an unsentimental, slightly jagged conversation about art, addiction, and aging, and not for anyone expecting neat gossip or a chronological “and then I did this film” highlight reel.

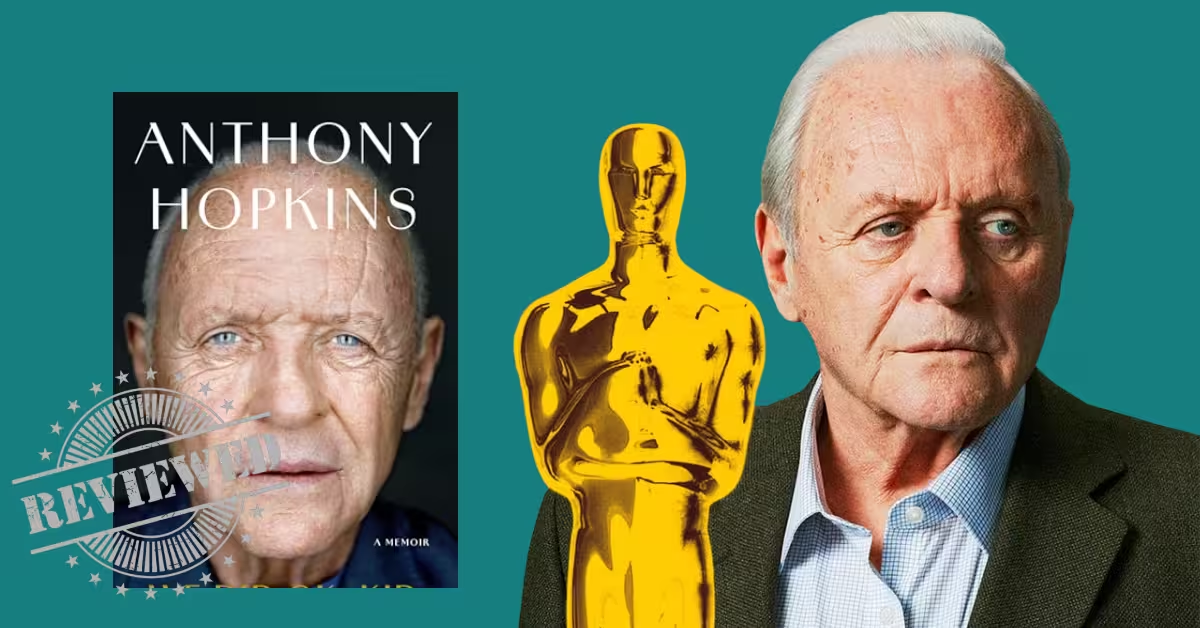

Published on 4 November 2025 by Summit Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, and running 368 pages, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is marketed as a “raw and passionate” life story that finally lets the man behind Hannibal Lecter speak in his own voice.

He revisits his childhood in the war-shadowed Welsh steel town of Port Talbot, the men who drowned feeling in alcohol, a long stage apprenticeship, the shock of global fame after The Silence of the Lambs, and the quieter late-life joys of painting and marriage.

Unlike many celebrity autobiographies, there is no ghostwriter named on the cover; critics in The New Yorker and elsewhere have pointed out how much the book sounds like Hopkins thinking out loud, in fragments that jump from past to present as if you’re listening to an extended monologue.

The purpose that emerges from that loose structure is simple but heavy: to understand how a bewildered boy who never felt “with it” grew into a man who caused damage, got sober, and is now trying to make peace with what he calls the mystery of his own life.

Formally, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is a memoir that doubles as a meditation on craft, because Hopkins can’t talk about life without talking about acting, and vice versa.

As publisher copy and early reviews underline, he moves between memories of tiny Welsh theatres and Leicester repertory companies, seismic roles in film and television, and interior turning points like winning a scholarship to drama college, entering AA in 1975, and meeting his third wife Stella, whose no-nonsense loyalty – friends call her “the Boss” – becomes an emotional anchor in his eighties.

His underlying argument, stated more in stories than in slogans, is that loneliness, anxiety, and addiction can be turned into fuel for art and for a more honest, if imperfect, adulthood.

When I read We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins for the first time, I kept feeling as if an older relative was muttering his way through stories at the kitchen table, occasionally wincing at himself and then shrugging, “Well, that’s how it went.”

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The memoir opens not with Hollywood but with a black-and-white photograph on Aberavon Beach in 1941, where three-year-old Tony drops a rare wartime sweet in the sand, bursts into tears, and is frozen on film beside his father.

From there, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins sketches a childhood of rationing, school failure, bullying, and a father who was emotionally distant yet fiercely practical, a baker-turned-publican whose world taught boys to work, drink, and keep quiet about feelings – a pattern that later interviews and biographies confirm across working-class Port Talbot.

Against that backdrop, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins traces the unlikely path from local scholarship winner – the Prince Littler Scholarship for Cardiff College of Music and Drama, announced in a tiny newspaper box – to professional training, repertory work, and eventually international cinema.

Along the way he remembers early mentors, humiliating auditions, and small acts of rescue: a Nottingham stage manager who notices a lost young man outside a Wimpy bar and steers him toward a badly needed backstage job, or a director who backs him after a furious outburst and tells him, in mock Latin, not to let the bastards grind him down.

Structurally, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is not a neat A-to-B timeline but a string of short, jagged sections that feel like monologues – critics in The New Yorker and The Independent both comment on its “stop–start rhythms” and “patchy” coverage, which skip entire films while dwelling intensely on childhood humiliation or a single AA meeting.

At the very centre of that structure stands Hopkins’s father, whose no-nonsense mantra – “Just get on with it… life is rough… never give in” – becomes the steel rod through the book, shaping both his fierce resilience and his lifelong habit of emotional evasion.

2. Background

In the wider cultural context, We Did OK, Kid arrives at an odd moment: Hopkins is approaching fifty years of sobriety, widely celebrated in interviews and on social media, and he’s one of the very few actors of his generation still working at the top level in his late eighties, with two Best Actor Oscars, dozens of nominations, and roles that run from Shakespeare to superhero movies.

The book also lands in a media climate fascinated by addiction stories; according to Newsweek and other outlets, Hopkins’s candour about driving blackout drunk from Arizona to Beverly Hills in 1975, realising he “could have killed somebody”, and then walking into AA gives his memoir a built-in hook that goes beyond ordinary celebrity confession.

Within that background, the title We Did OK, Kid – drawn from what he says to the little boy in the beach photograph – carries extra weight: it’s a verdict not of perfection but of survival after a life that statistics suggest should have ended in a ditch or in a hospital decades ago.

Against this real-world frame, the book’s interior world feels more intimate: Hopkins writes about his volatile temperament, his bouts of anger and depression, and the patterns of self-sabotage that damaged his first two marriages, including the decades-long estrangement from his daughter Abigail, which recent coverage in People and Entertainment Weekly has highlighted as one of the memoir’s rawest threads.

He also positions his craft against that inner chaos, echoing interviews where he downplays acting as “just a job”: in the book, painstaking accounts of learning lines, controlling stillness on camera, and designing Hannibal Lecter’s chillingly polite presence show how he built an external discipline strong enough to contain a mind that often felt like it was falling apart.

3. We Did OK, Kid Summary

We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins reads like one long, looping conversation between an 87-year-old actor and the frightened little boy he once was, stitching together war-time Wales, West End stages, Hollywood sets, blackouts, AA basements and late-life calm into one jagged but ultimately gentle life story.

From the very first image—a three-year-old Anthony on Aberavon Beach in 1941, sobbing because he’s dropped a precious cough lozenge during wartime rationing, then later looking back at that photo and telling the boy, “We did OK, kid”—the memoir establishes its frame: an anxious child who never quite feels “with it,” yet somehow survives and even thrives.

It then follows him through the industrial town of Port Talbot, where his no-nonsense baker father, Richard, and tough, unsentimental grandfather Fred drill into him a simple creed—“Life is rough. So what? Never give in,” as his father likes to say, while insisting that people should “just bloody get on with it” rather than agonise over the meaning of life.

Across the book, Hopkins keeps circling back to that early mixture of bewilderment and grit, using it as the emotional compass that explains his isolation, his explosive temper, his alcoholism, and his relentless work ethic.

As a reader you’re taken next into the brick-red “prison” of West Mon boarding school in 1949, where eleven-year-old Anthony is dumped on a hill above Pontypool and immediately branded “Elephant Head” by the headmaster, J. Idwal Rees, whom he nicknames “the Crow.”

Rees publicly calls him “totally inept,” sneers at his “shovel hands,” and literally slaps him while demanding whether anything goes on “in that thick skull” of his; Hopkins describes how he takes this humiliation and turns it into an identity, going to the public library to look up inept in Webster’s and feeling perversely proud to “own the page” listing synonyms like “incompetent” and “unfit.”

Those scenes lay the groundwork for a lifelong sense of being the outsider in every room, even when he’s later standing on Oscar stages.

Soon after, the memoir shifts to the more hopeful refuge of Port Talbot YMCA and the terrazzo floor where he first steps onstage, playing Pontius Pilate in an Easter play.

That little amateur drama, he later realises, is the hinge on which the whole life swings: the first place where words, audiences, and escape from himself all line up.

From there, We Did OK, Kid moves through a drifting adolescence in which Hopkins fails exams, wanders the Welsh hills, and clowns around doing impressions of Bela Lugosi, Bugs Bunny and Boris Karloff to impress schoolmates, discovering that he can copy any voice he hears and even make animals’ sounds convincingly.

He lands, almost by fluke and family lobbying, at Cowbridge Grammar School, whose elite atmosphere and hyper-classical headmaster only deepen his feelings of stupidity and clumsiness, but where he also falls in love with libraries, notebooks and words.

The background of World War II permeates these chapters: American soldiers billeted at Margam Castle, GIs blowing up mines near Porthcawl—“OK, step back! … Boom!”—and house-guest soldiers like Cooney and Durr who matter-of-factly admit their fear that they may never see their children again, giving young Anthony his first glimpse of adult mortality.

All of this childhood material builds toward one central point: he feels like a misfit and a “brainless cart horse,” but he’s quietly loading up on voices, images and sensations that will later become raw acting material.

The middle third of the memoir tracks the uncertain, almost chaotic slide from those Welsh days into a professional acting life that, on paper, looks linear—drama school, repertory theatre, National Theatre, films—but in Hopkins’s telling is messy, full of sackings, self-sabotage and sudden rescues.

We watch him, still wild and undisciplined, crash through early repertory jobs in places like Manchester, where director Henry Scase finally fires him for dangerous stage-fighting and lack of technique, bluntly telling him he has presence but “no technique” and needs proper training at RADA or LAMDA if he’s ever going to amount to anything.

Hopkins accepts this with his characteristic monosyllabic “OK,” then impulsively sneaks out of the theatre without collecting his last week’s pay, boards a train to Nottingham with a small suitcase and ten pounds in his pocket, and reframes it all in his head as a film scene—himself as a convict escaping prison, the whistle blowing on a new reel of life.

Those years also include National Service in the late 1950s, where he proves equally hopeless at military life, fails at marching, and ends up typing in the regimental office while dodging the wrath of a sergeant major, adding another layer to the theme that he’s always in the wrong uniform, the wrong role, until acting gives him one that fits.

Gradually the narrative widens to his entry into serious theatre: drama school in London, early Shakespeare productions, and his crucial audition for Laurence Olivier that leads to a place at the National Theatre in the mid-1960s, where he understudies and sometimes replaces the great man himself in roles like Othello and King Lear.

Here, Hopkins alternates awe with irritation, recalling Olivier’s brilliance onstage and his sharp, often cruel remarks offstage, and reflecting on how much he learned about preparation—rehearsing lines like “picking up stones from a cobblestone street one at a time” until the whole road is memorised.

Parallel to the professional ascent, We Did OK, Kid lays out the breakdown of his personal life: early marriages, constant affairs, and the painful estrangement from his daughter, Abigail, whom he left as a baby when he abandoned his first marriage in the early 1970s.

He writes about this with a mixture of shame and numbness, comparing himself to his grandfather who refused to speak about a dead child because “the memory is too painful,” and confessing that he has sometimes spoken coldly about Abigail in interviews as a way of armouring himself against grief, even as he insists that his “door is always open to her” and that he will never forget seeing her laughing in her crib.

As the narrative reaches the 1970s, the book’s emotional centre of gravity shifts decisively to alcohol and what it almost cost him.

Even before fame truly hits, Hopkins is drinking heavily in London and New York, staying late at bars after performances and building a reputation as both a fierce actor and a chaotic colleague.

In January 1975, during his Broadway run in Equus, he collapses with agonising pain in his calf and is diagnosed with thrombosis at Mount Sinai Hospital; the doctor coolly informs him that a stray clot could kill him and gently raises the question of whether his nightly drinking at Charlie’s bar might have something to do with his condition.

Hopkins recalls this with black humour but also sees it, in hindsight, as one of the early warning bells he ignored.

The real bottom arrives the following year in Los Angeles, after a cross-state drive from Arizona in a drunken blackout, when he’s informed by his agent that he was found on the road and could easily have killed a family or ended up in jail, an episode that leaves him staring up at eucalyptus trees and hearing an internal voice ask, “Do you want to live or do you want to die?”

He answers silently that he wants to live, hears another inner voice tell him, “It’s all over now. You can start living,” and notes with almost clinical amazement that “the craving to drink left me” at eleven o’clock on December 29, 1975, a moment of grace he still can’t fully explain nearly fifty years later.

The very next day he is taken by friends Bob and George to his first AA meeting, where he recognises himself in a truck driver’s story and realises with relief that the room is full of fellow “misfits” who feel they never belong and are eaten up by self-hatred, and he adopts Bob’s simple advice: “Keep it simple. Go to meetings. Stay in contact,” a rhythm he maintains for decades.

From this point on, the memoir is as much about sobriety as about stardom.

Hopkins recounts how sobriety allows him, for the first time, to apologise properly to his parents when they visit California in 1977, taking them to Disneyland, film sets and Beverly Hills, where his father tears up when John Wayne shakes his hand and calls his son “a heck of an actor,” a moment that symbolically redeems years of mutual disappointment between father and son.

Professionally, the late 1970s and 1980s become the era of his key screen work: he plays King Richard in The Lion in Winter (1968), the haunted magician in Magic (1978), and Dr. Frederick Treves in The Elephant Man (1980), a black-and-white film shot in the crumbling docklands of East London, where he finds himself unexpectedly moved when his character first discovers John Merrick in a nightmarish cellar.

Interestingly, as several reviewers have noted, Hopkins often glides over the technical details of his movie career, offering sharp vignettes rather than exhaustive production histories, a choice that has led outlets like The Independent to observe that the memoir “is hesitant to really discuss his film career much at all,” focusing instead on personal wounds and recoveries.(The Independent)

Still, some iconic roles do get close attention, especially Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), for which he won his first Academy Award at age 53, and which he explains partly through his childhood impressions of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula and the icy, penetrating gaze of his RADA teacher Christopher Fettes, as well as his insistence that Lecter be “extremely civilized,” standing perfectly still in a tailored jumpsuit when Clarice Starling first meets him in his cell.

In these chapters, We Did OK, Kid quietly links his childhood strategies of “dumb insolence”—the decision to stay mute and unreadable in the face of bullying—to the crafted stillness of characters like Lecter or the butler Stevens in The Remains of the Day (1993), which he plays by making rooms feel “even emptier” when the butler is present and by minimising his speech and movement to almost nothing.

The later chapters, written from the vantage point of an octogenarian with dual UK–US citizenship and two Oscars (1991, 2021), become more reflective, even meditative.

Hopkins describes marrying his third wife, Stella Arroyave, in a small Malibu ceremony where a pastor and a Buddhist monk jointly officiate, his mother unexpectedly bonding with Mickey Rooney at the party, and then, not long after, his mother’s death at 89, which he meets with his familiar, flat “Oh… OK” before later acknowledging how deeply her long, hard life shaped him.

He moves between anecdotes of film sets and quiet domestic scenes—Stella encouraging his painting and music, his growing comfort with solitude, his fascination with death as “just another fact” that will arrive when it arrives, the mantra that gives its title to a chapter called “Death Will Come When It Comes.”

He also writes about kindness and professionalism, describing how he now makes a point of talking to crew members on set, reminding younger actors that the people “plugging in the lights” and “driving the trucks” are the ones who actually put their “stupid faces” on the screen, and that arrogance towards them is intolerable.

Late in the book, he even experiments with filmmaking himself through the surreal, stream-of-consciousness movie Slipstream (2007), which he co-creates with Stella, acknowledging that it baffled many viewers but cherishing it as a playful, personal project that mirrors the non-linear way his own mind works.

By the closing pages, We Did OK, Kid has looped back to where it started: a man in his late eighties glancing at an old black-and-white photograph of a crying toddler in the dunes and realising, with some surprise, that the confused, lonely boy who once dropped a sweet in the sand survived war, bullying, self-loathing, addiction, regret and global fame, and somehow turned it into a life that—while far from tidy—feels, in his own understated phrase, like “OK” was more than good enough.

4. We Did OK, Kid Analysis

In terms of content, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins is at its strongest when Hopkins uses precise, sometimes brutal scenes to support his reflections rather than drifting into aphorism; he describes the blackout drive in 1975 that could have killed someone, the doctor who quietly lists evidence of organ damage, the childhood verdict that he was “bloody useless”, and the night his anxiety nearly derailed him before stepping into Hannibal Lecter’s skin for the first time.

Those episodes are backed up by decades of journalism: according to The Guardian and other outlets, Hopkins entered AA at the end of December 1975, has remained sober for almost fifty years, and still marks 29 December as the day his life turned – a detail the memoir returns to with almost religious awe.

Industry statistics also underline what his self-deprecating tone skims over; he has appeared in more than ninety screen projects, won two Oscars out of six nominations, and piled up BAFTAs, Emmys, and knighthood, so when he mutters that acting “sure beats working”, it reads as the gallows humour of someone who has quietly dominated his field for half a century.

The book’s thesis – that early damage can be transformed into art and, more importantly, into a liveable late life – is therefore not just memoir logic but is corroborated by these external numbers: without that 1975 turning point, there is no Remains of the Day, no Nixon, no late-career triumph in The Father.

From a critical point of view, We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins contributes meaningfully to both addiction writing and actor memoirs by showing, in almost case-study detail, how a self-destructive pattern can be interrupted and replaced with a disciplined, nearly obsessive devotion to craft and routine, something recovery literature and Alcoholics Anonymous histories often emphasise as crucial for long-term change.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

My own reading experience was that the strengths of We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins lie in its emotional honesty and its refusal to flatter either reader or author: he admits to infidelity in his twenty-year marriage to Jennifer Lynton, to failing Abigail as a father, and to retreating into rage or icy withdrawal when things became difficult, and he does so without tacking on easy absolution or inspirational spin at the end of each chapter.

The weaknesses are real too – the narrative can lurch abruptly, leaving out entire eras of work, some iconic films are mentioned only in passing, and Hopkins sometimes leans on cryptic musings about fate or “the big skedaddle” instead of digging further into his psychology, so readers who want a tidy, chronological filmography or a fully resolved therapeutic arc may feel frustrated, a point echoed by reviewers in outlets like The Independent even as others praise the book’s candour and eccentric charm.

6. Reception

Early reception of We Did OK, Kid has been broadly positive but intriguingly split, with review aggregators noting a “Positive” overall score while individual critics diverge between calling it searingly honest and mildly disappointing in its coverage of his storied career.

Some, like Newsweek and The Guardian, highlight the book’s influence as a sober, late-life testimony: they point to his nearly fifty years without alcohol as a kind of cultural lighthouse, especially when he posts annual Instagram messages urging people struggling with addiction to seek help, and they argue that the memoir will be read not only as film history but as a manual of survival.

Others, such as The Independent and The New Yorker, are more reserved, observing that the book is “patchy” and omits whole swaths of his achievement, but they still admit that its stop-start, Beckett-like rhythms capture something true about a mind that has always felt ambushed by its own doubts and “Welsh saboteurs”.

Comparison with similar works

When I place We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins alongside other contemporary creative memoirs, it feels like a rougher, more self-questioning cousin to Matthew McConaughey’s Greenlights and Bryan Cranston’s A Life in Parts – less neatly structured than either, but more haunted by guilt and by the question of whether success can ever compensate for the people you’ve hurt.

7. Conclusion

Overall, if I had to recommend We Did OK, Kid: A Memoir by Anthony Hopkins to someone, I would say it belongs to anyone who is curious about how a human being can be both deeply broken and quietly functional, and that what you’ll find here is not a glossy Wikipedia-style summary but a living, uncomfortable, strangely consoling voice that keeps repeating to a bewildered child on a wartime beach – and, by extension, to us – that despite everything, we did OK.