A Clockwork Orange (1971) still feels like a dare—less “watch me” than “what will you do with what you’ve just seen?”

I first met Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) the way many people do: with a mix of curiosity and a little dread.

It’s a dystopian crime film, written and directed by Kubrick, adapted from Anthony Burgess’s novel, and it premiered in late 1971 before rolling into wider release in 1972. What makes it endure isn’t just its notorious violence, but the cold intelligence behind it—an argument disguised as a nightmare.

If you’re here for a simple verdict, mine is this: A Clockwork Orange (1971) is brilliant, disturbing, and weirdly funny in the bleakest way. It’s also one of those films that changes shape depending on your age, your politics, and your tolerance for moral discomfort. Even when I disagree with its emotional distance, I can’t deny how sharply it slices.

It’s no accident that A Clockwork Orange (1971) became a cultural reference point rather than a normal “classic.”

Table of Contents

Background

A Clockwork Orange (1971) was made on a comparatively small budget—about $1.3 million—and went on to gross roughly $114 million worldwide, which still amazes me given how confrontational it is.

It runs 136 minutes, stars Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge, and features music credited to Wendy Carlos that helps give the film its eerie, synthetic elegance.

If you want a shorthand description, the BBFC calls it a dystopian science-fiction story about a violent gang leader, but the film’s real subject is power: personal power, state power, and the sick bargain between them.

The film’s afterlife is almost as famous as the film itself. It was controversial on release, and Kubrick later had it withdrawn from UK circulation; whether people label that “banned” or “withdrawn,” the key point is the same: A Clockwork Orange (1971) became “the movie you couldn’t see,” and that scarcity only sharpened its legend. You can feel that history humming underneath modern rewatches, like a second soundtrack made of headlines and arguments.

Critically, it sits in that rare space where institutions and troublemakers both claim it. In 2020, the Library of Congress selected A Clockwork Orange (1971) for the National Film Registry, marking it as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

On the canon side, it has also appeared in the wider gravitational field of “greatest films” conversations, including the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound ecosystem.

Awards-wise, the most concrete headline is that it earned four Academy Award nominations at the 44th Oscars: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Film Editing. That recognition matters to me because it confirms something I often forget while watching: the industry did understand it as major art, not just scandal, even in the heat of its controversy.

If you’re exploring Kubrick on probinism.com, an internal pairing I genuinely recommend is my piece on Lolita—another Kubrick work where desire, control, and censorship collide in uncomfortable ways, just with a very different temperature.

A Clockwork Orange Plot Summary

A Clockwork Orange (1971) opens by staring straight back at you through Alex DeLarge’s eyes.

He’s young, charismatic, and already corrupted in the way only a teenager can be—performatively, gleefully, like evil is a fashion choice he’s convinced will never go out of style. Alex lounges in the Korova Milk Bar with his “droogs,” drinking drug-laced milk and talking in that stylised slang that turns cruelty into a kind of sing-song.

Kubrick makes the place feel like a museum exhibit for a future that hates itself: white, clinical, and decorated with bodies as furniture.

From the beginning, Alex narrates as if he’s the hero of his own private opera.

His voice is charming, but it’s also a warning: you’re about to be seduced into following someone you shouldn’t follow. Alex and his droogs roam the night hunting for entertainment, and their entertainment is domination—over strangers, over rivals, over anyone unlucky enough to be nearby.

The violence comes in bursts that feel choreographed, and that’s part of what unsettles me: it’s not chaos, it’s performance.

They assault a homeless man, then brawl with a rival gang in a derelict theatre, like street brutality staged as a parody of art.

It doesn’t stay “impersonal” for long.

In one of the film’s most infamous sequences, Alex leads an invasion of a writer’s home and commits sexual violence while singing “Singin’ in the Rain,” twisting a cheerful cultural artefact into a weapon.

Kubrick’s choice to associate horror with a tune people once trusted is deliberate—it’s how the film shows contamination spreading, not just in society but in the audience’s memory. I can’t hear that song the same way after this film, and I don’t think Kubrick wants me to.

After the spree, ordinary life intrudes in a way that almost feels like satire. Alex has a probation officer who scolds him, as if the problem is his attitude rather than the wreckage he leaves behind. At home, his parents are small, tired figures, outmatched by their son’s appetite for cruelty and by the society that produced him. Even the domestic scenes feel sterile, like the whole culture has become a waiting room where nobody is being treated.

Then comes the first major shift: betrayal from within the gang.

Alex’s droogs begin to resent him, partly because he bullies them and partly because he insists on being the star of every crime.

They want bigger jobs and more equal spoils, and Alex responds the way he always does: with violence that reasserts his authority.

When they target a wealthy woman—often remembered as the “cat lady”—the crime spirals into murder, and Alex’s escape fails because the boys he led decide they’re done following.

Dim strikes Alex, leaves him behind, and the police catch him in the aftermath.

Alex is sentenced to prison, and the film becomes, briefly, a different kind of story: not about roaming freedom, but about caged power.

In prison, he’s still Alex—still smug, still performing—but now the performance is survival. He tries to ingratiate himself with authority, learns how to look “reformed,” and even finds a perverse comfort in routines, as if structure can replace conscience.

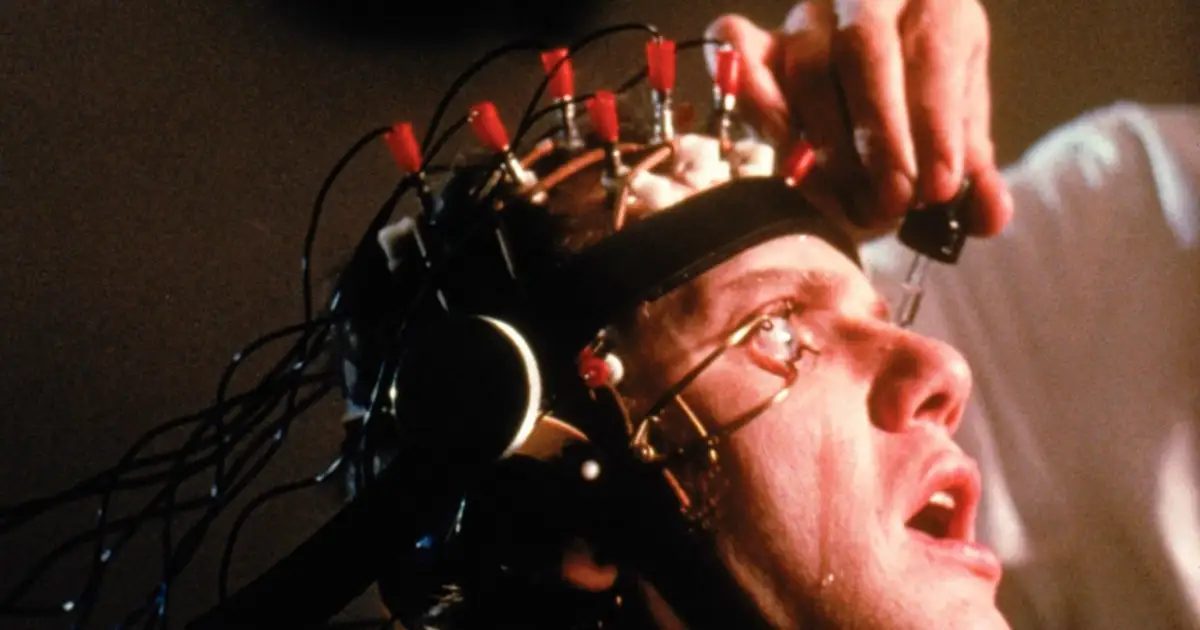

Two years into his sentence, the state offers him a deal dressed up as salvation: the Ludovico Technique.

This is the film’s central pivot, and it’s where A Clockwork Orange (1971) stops being “just” a story about a violent delinquent and becomes a story about what governments do when they get tired of messy human beings.

Alex volunteers because he wants out, not because he understands what he’s trading. The treatment is simple in concept and monstrous in application: he’s drugged, strapped to a chair, his eyes forced open, and he’s made to watch images of sex and violence until his body learns to associate those impulses with nausea and terror.

The cruelty is clinical, which is Kubrick’s point.

Here, the state doesn’t look like a thug in the street; it looks like professionals in white coats, taking notes while a human being is reduced to a mechanism.

Alex’s love of Beethoven becomes collateral damage when the therapy pairs his beloved music with the images, so that beauty itself becomes unbearable to him. Watching it, I’m struck by how the film refuses easy alignment: Alex deserves punishment, but what’s happening to him is also a violation, and the film forces you to hold both truths at once.

When the government demonstrates the “cure,” it’s staged like theatre.

An actor provokes Alex, even hits him, and Alex cannot fight back—his body locks into sickness when he tries.

A topless woman is presented as temptation, and again he becomes nauseated, humiliated in front of officials who clap for the success of their technique.

The prison chaplain objects on moral grounds, arguing that goodness without choice is not goodness at all, but the Minister doesn’t care; he speaks in the language of efficiency—reduced crime, reduced prison crowding, reduced problems.

Then Alex is released, and the film becomes cruel in a new way: the world he terrorised is waiting to terrorise him back.

His parents have effectively replaced him, renting out his room, treating him like a shameful inconvenience rather than a son.

His possessions are gone, sold to compensate victims, and the city feels suddenly hostile because he no longer has the power that once made him fearless.

A homeless man—one of his earlier victims—recognises him and gathers others to beat him, and for the first time Alex experiences what it’s like to be on the receiving end with no exit and no strength.

The bleak joke continues when the police arrive, because the police are his former droogs.

Dim and Georgie have traded gang uniforms for badges, and the film practically underlines its own argument: society hasn’t eliminated violence, it has just rehoused it inside institutions. They beat Alex, nearly drown him, and abandon him, not as a “lawful consequence” but as personal revenge with official cover.

This is one of the moments that always makes my stomach drop, because it reveals how thin the line is between criminal brutality and sanctioned brutality when the same people can pass through both doors.

Half-dead, Alex collapses on the doorstep of a house that turns out to belong to the writer from the earlier home invasion.

The writer—now wheelchair-bound—doesn’t recognise him at first, and that delay is crucial: it allows Alex to be cared for as a suffering human being before he’s reclassified as a monster again.

The writer and his circle are political dissidents who already oppose the government’s Ludovico program, and Alex—unwittingly—looks like a perfect symbol for their cause. They feed him, shelter him, and plan to use his story to embarrass the state.

But the past comes back through something as small, and as poisonous, as a song.

Alex sings “Singin’ in the Rain” while bathing, and the writer suddenly recognises him as the attacker who destroyed his life and killed his wife.

The hospitality curdles into revenge almost instantly. Alex is drugged, locked in a room, and the writer plays Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at full volume from below—weaponising the very trigger the Ludovico Technique implanted. Alex’s body reacts with unbearable sickness and panic, and the “cure” becomes a lever someone else can pull whenever they want.

Desperate to escape the sensation, Alex throws himself out of the window in a suicide attempt.

He survives, wakes in hospital with severe injuries, and the politics snap into place like a trap: the government doesn’t want a scandal, especially not one involving a rehabilitated poster-boy attempting suicide under dissident care. During recovery, Alex discovers the conditioning has been reversed—he can think about sex and violence again without sickness.

The Minister arrives, apologises with a politician’s smile, and offers Alex a deal: cooperate with government publicity, and you’ll be rewarded with comfort, status, maybe even a job.

This is where the ending of A Clockwork Orange (1971) lands its final, icy punch.

Alex imagines violent, sexual fantasies while the Ninth Symphony plays, and he thinks the film’s famous closing line: “I was cured, all right!”

The words are sarcastic, triumphant, and horrifying at the same time, because the “cure” the state wanted was never moral reform; it was control and optics, and now they’ve found a way to keep Alex close, useful, and smiling for cameras.

Kubrick ends on that grin because it’s the most honest image in the film: a monster welcomed back into society, not because he’s changed, but because he can be managed.

If you’ve read Burgess’s novel, it’s worth noting that Kubrick’s ending is darker than the book’s original final chapter, which offers a more explicit turn toward maturity. Kubrick’s screenplay was influenced by an edition that omitted that last chapter, and the film leans into the bleak implication that Alex remains Alex—only now he’s been absorbed into the system.

For me, that choice is why A Clockwork Orange (1971) still stings: it refuses to reassure us that time, or therapy, or punishment automatically produces goodness.

Cast

- Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge – the iconic antihero whose charm, violence, and loss of free will define the film

- Patrick Magee as Frank Alexander – the writer whose personal tragedy fuels political manipulation and revenge

- Adrienne Corri as Mary Alexander – a pivotal victim whose assault becomes central to the film’s moral argument

- Carl Duering as Dr. Brodsky – the lead scientist behind the Ludovico Technique, symbolizing cold state control

- Madge Ryan as Dr. Branom – the clinical overseer of Alex’s conditioning, representing detached psychology

- Anthony Sharp as Frederick, Minister of the Interior – a satirical portrait of political power and propaganda

- Aubrey Morris as P. R. Deltoid – Alex’s manipulative parole officer, blurring guidance and coercion

- Godfrey Quigley as Prison Chaplain – the moral voice warning against punishment without free choice

- Michael Bates as Chief Guard Barnes – the embodiment of institutional cruelty and abuse of authority

- Warren Clarke as Dim – Alex’s former droog, later an agent of state violence, showing power’s rotation

A Clockwork Orange Analysis

Whenever I revisit A Clockwork Orange (1971), I’m struck by how Kubrick turns style into a moral interrogation rather than decoration.

Stanley Kubrick directs A Clockwork Orange (1971) like a composer, building movements that rise from playful swagger to institutional horror.

BFI notes that with A Clockwork Orange (1971) he was trying to deconstruct classic Hollywood narratives and make cinema behave like music, and you can feel that rhythm in the way scenes snap from seduction to punishment. That approach also makes the film perfect for my 101 must-watch films list on probinism.com, because it’s not just a story—it’s a controlled experiment on the viewer.

Visually, A Clockwork Orange (1971) feels both recognisable and wrong, as if modern Britain has been rearranged into a threat. BFI describes how Kubrick “morphed” London by splicing locations—often brutalist concrete backdrops—into an ominous futuristic maze.

Even if you’ve never seen A Clockwork Orange (1971), you probably know the droogs’ white uniforms and bowler hats, which BFI argues have become an enduring style template rather than a period detail.

Acting Performances

Malcolm McDowell’s Alex is the engine of A Clockwork Orange (1971), and the performance is so charismatic that it practically implicates you.

McDowell plays Alex with a boyish grin that can flip into predator stillness in a blink, which is exactly how the film keeps you off balance.

Patrick Magee’s Frank Alexander brings a different kind of menace—educated, articulate, and eventually consumed by revenge—so the film can argue that cruelty isn’t owned by one class or one ideology.

Michael Bates, as Chief Guard Barnes, embodies the everyday bureaucratic sadism of the prison system, which makes the later “treatment” feel like an extension of routine rather than a shocking exception.

What I find most chilling is how the supporting cast often mirrors Alex back at him: the state uses his theatricality when it needs publicity, and the victims become violent once they get their chance.

BFI’s credits list underlines how tightly Kubrick chose these faces and voices—McDowell, Magee, Bates and others—like parts in a grim symphony.

Script and Dialogue

Kubrick’s adapted screenplay (nominated at the Oscars) keeps Burgess’s Nadsat slang as a kind of poetic camouflage, so brutality arrives wrapped in wordplay. Sometimes the pacing feels deliberately repetitive—like the film is daring you to get bored before it shocks you again—but that repetition also supports the theme of conditioning.

That same push-pull between pleasure and punishment is even clearer once you listen to how A Clockwork Orange (1971) uses music.

Music and Sound Design

The score of A Clockwork Orange (1971) weaponises beauty, especially through electronic reworkings of Beethoven that make the sublime feel slightly sick.

Wendy Carlos and producer Rachel Elkind built a soundscape where classical pieces are filtered through early synthesizer technology, so the future sounds both familiar and alien.

In Carlos’s own notes, she describes experimenting with a “spectrum follower” device that could translate vocal sound into electronic signals—part of how the film’s choral textures become uncanny.

For me, that blend matters because it turns Alex’s beloved Beethoven into a control mechanism, not just a soundtrack choice.

Kubrick also corrupts pop memory by pairing violence with cheerful tunes like “Singin’ in the Rain,” a tactic BFI links to his habit of perverse musical retooling.

BFI has even traced how A Clockwork Orange (1971) helped set the scene for punk—partly because its sound-and-style package made rebellion look like a uniform you could buy.

A Clockwork Orange Themes and Messages

All of this sound and image funnels into the film’s central question: is a person still human if goodness is forced onto them?

A Clockwork Orange (1971) is basically a debate about free will versus social order, staged with the confidence of a nightmare that knows it’s right.

The Ludovico Technique is the film’s sharpest metaphor, because it shows a state that would rather manufacture obedience than wrestle with the messy roots of violence. BFI frames the film as a powerful essay on the pleasures and consequences of physical and psychological violence, and I read it as a warning about how easily “public safety” becomes an excuse for moral shortcuts.

The irony is that the world outside Alex is already sick: the police can become thugs, political dissidents can become torturers, and the victim-vs-villain categories collapse into a circle.

When I watch A Clockwork Orange (1971) now, it also feels like a story about optics—how governments sell solutions, how media sells outrage, and how the public often accepts any cure as long as it’s quick.

BFI’s wider look at British dystopias argues that changing nightmares about the future reflect the pressures of the present, and this film’s nightmare is that we’ll trade choice for comfort and call it progress.

Comparison

If you’re mapping A Clockwork Orange (1971) among dystopias, it sits in the same anxious family as Orwell-adjacent futures like 1984, but it’s far more interested in pleasure—how violence seduces before it destroys.

Within Kubrick’s own filmography, it shares Dr. Strangelove’s darkly comic cynicism and anticipates the institutional cruelty of Full Metal Jacket, yet BFI’s Sight & Sound listing shows it remains a singular provocation rather than a repeatable formula.

Audience appeal and reception

If you’re drawn to cinema that refuses to soothe you, A Clockwork Orange is aimed squarely at your nerves.

It’s best suited to adult viewers who can handle graphic sexual violence and cruelty without confusing discomfort for “the film endorses it.” The experience rewards cinephiles—especially anyone interested in how form (lenses, staging, sound) can make a moral argument—more than casual viewers looking for a conventional crime story. On release it split critics, but it later built a long afterlife as a cult classic.

Today, aggregators still reflect that mix of admiration and unease: Rotten Tomatoes shows an 86% critics score (with review count displayed on the page), and Metacritic lists a 77 metascore.

One practical warning: the film’s notoriety isn’t just marketing history—it was linked in public debate to copycat violence and was withdrawn from UK release for decades at Kubrick’s request.

Awards

It received four Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture.

Those nominations (as commonly listed) include Best Picture, Best Director (Stanley Kubrick), Best Writing—Adapted Screenplay, and Best Film Editing.

In the US, it was also selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2020.

And yes—on my own site’s long watchlist logic, it earns its place: it’s included in my “101 Best Films You Need to See” list.

Personal insight and lessons today

Some films shock you once; A Clockwork Orange keeps rearranging the furniture in your head every time you return to it.

The older I get, the less I see it as “a movie about violence,” and the more I see it as a movie about permission—who gets to hurt, who gets to punish, and who gets to call it progress.

Kubrick makes Alex unbearable, but he also makes him useful to people with cleaner suits and dirtier hands. The film’s political sting is that both “sides” are willing to manipulate the same human body for power.

That feels painfully current in an age when we’re constantly being nudged—by governments, institutions, platforms, and even our own social circles—toward the “right” reactions.

Two parties can argue all day about morality while quietly agreeing on one thing: the citizen should be predictable. The film’s world doesn’t just fear crime; it fears unmanaged people.

The Ludovico Technique is the film’s most famous invention, and it still lands because it turns a philosophical debate into a physical horror.

The story openly links what happens to Alex to behaviourism and conditioning—reward, punishment, and the dream of engineering human choice. It’s not subtle about how that dream can slide into authoritarian control.

In 2025, I can’t watch those scenes without thinking about how often we confuse “less visible harm” with “real reform.”

We love solutions that are neat, measurable, and quick, especially when we’re scared. But the film insists that if you remove agency—if you make someone “good” by force—you haven’t built morality; you’ve built a puppet that can’t resist anyone.

That’s the nightmare behind the title: a living thing turned mechanical, bright on the outside and broken within.

There’s another lesson that bites even deeper: public outrage can be sincere and still become a tool. The film’s history—its controversy, the fear of copycat violence, the UK withdrawal—shows how easily art gets drafted into moral panic, then used as evidence for wider control.

Kubrick’s own pushback is worth sitting with because it refuses the comforting simplicity of “one film caused one crime.” Even if you disagree, the point stands: blaming art can become a shortcut that avoids confronting the harder causes underneath.

So my takeaway isn’t “this is what humans are,” or “this is what society does.”

It’s that brutality and control can share the same language—safety, order, rehabilitation—until you’re applauding the cage because it’s painted nicely. And once you see that trick, you start noticing smaller versions of it everywhere.

A Clockwork Orange Quotes

- Frank Alexander’s warning about the “thin end of the wedge” toward totalitarianism: “Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police… techniques of conditioning… the full apparatus of totalitarianism.”

- Roger Ebert’s first-pass verdict—brutal, memorable, and still debated: he called it an “ideological mess.”

- Vincent Canby, praising the craft while admitting the danger: “McDowell is splendid… it is always Mr. Kubrick’s picture.”

- Kubrick on the temptation to blame art for life (excerpt): “Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life.”

Pros and cons

Pros

- Bold, unmistakable direction with image-and-sound ideas that stay with you

- Malcolm McDowell’s performance is magnetic in the most unsettling way

- Themes about control, “rehabilitation,” and political exploitation still feel sharp

Cons

- The sexual violence is extreme and can feel unbearable (and that may be a deal-breaker)

- Its coldness can read as detachment; some viewers experience it as empty provocation

Conclusion

I don’t “enjoy” A Clockwork Orange so much as I endure it—and then think about it for days.

As a piece of filmmaking, it’s disciplined, inventive, and perversely elegant; as a moral experience, it’s intentionally destabilising. If you want a safe watch, skip it, but if you want a film that argues with you—about free will, punishment, and the state’s hunger for tidy solutions—this is essential.

Recommendation: a must-watch for serious cinephiles and dystopian-crime film lovers, with strong content cautions.

Rating

4.5/5 — not because it’s “pleasant,” but because it’s relentlessly purposeful.