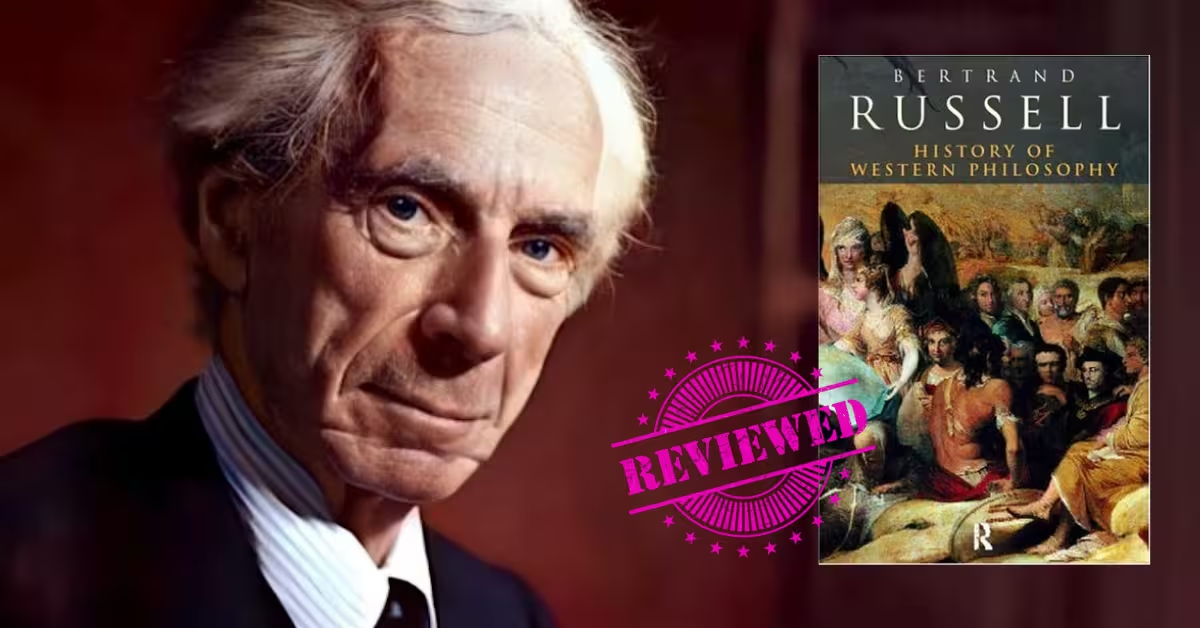

If philosophy often feels like a maze, Russell hands you a map. History of Western Philosophy compresses 2,500 years of argument into one book—and shows how ideas and power shape each other.

Russell’s thesis is that philosophy lives in a no-man’s-land between science and theology and is both a product of its age and a force that remakes that age.

Evidence snapshot:

- Written after 1941–42 Barnes Foundation lectures; composed 1944–45; published 1946 (UK) and 1947 (US); long a commercial success.

- Routledge’s modern edition lists 792 pages and calls it “the best-selling philosophy book of the twentieth century.”

- The book helped secure Russell’s 1950 Nobel Prize in Literature (named among works in the Nobel materials).

- Contemporary and later reception: widely praised for clarity and wit, faulted for overgeneralization—documented by Grayling, Boas, Copleston, Scruton, among others.

Best for / Not for:

- Best for: Curious general readers, students, journalists, and autodidacts who want a single-volume tour of Western thought with context and bite.

- Not for: Readers seeking a neutral textbook or exhaustive scholarship on, say, Kant’s Transcendental Dialectic—Russell is selective, opinionated, and sometimes unfair.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell is the one-volume classic people still reach for when they want a brisk, combative, brilliantly readable guide to Western philosophy’s big arcs. First published in two markets (UK 1946; US 1947) and repeatedly reissued, History of Western Philosophy remains in print because Russell makes arguments feel alive.

Full title: A History of Western Philosophy and Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day—the British editions dropped the initial A. Author: Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), Nobel laureate, foundational figure in analytic philosophy.

This is a narrative survey of Western philosophy written by a logician who co-authored Principia Mathematica and helped define analytic philosophy. (For Russell’s standing as a central figure in the analytic tradition, see standard references.)

Russell says philosophy sits “between theology and science” and studies questions science cannot adjudicate and theology over-answers; the historian of philosophy must show how ideas and institutions co-produce one another. He famously adds that philosophy’s modern task is “to teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralysed by hesitation.”

Russell: “There is here a reciprocal causation… the circumstances of men’s lives do much to determine their philosophy, but, conversely, their philosophy does much to determine their circumstances.”

2. Background

Russell frames the story in three great periods—ancient (Greece to late antiquity), medieval (dominated by the Church), and modern (dominated by science)—stressing the tug-of-war between social cohesion and individual liberty.

He wrote the book out of WWII-era lectures (Barnes Foundation) and openly thanks Dr. Albert C. Barnes for the platform that made the project possible. The modern Routledge edition runs 792 pages; the structure spans three books and dozens of chapters from the Presocratics to logical analysis.

3. Summary

Book I : Ancient Philosophy

Part I : The Pre-Socratics

1. The Rise of Greek Civilization (1200 BCE – 323 BCE.)

Russell frames the sudden ascent of Greek civilization as historically unique: Egypt and Mesopotamia had long supplied the infrastructure of culture—writing (c. 4000 B.C. in Egypt) and organized states—but Greece injected free philosophy, science, and history without priestly orthodoxy.

I find this profoundly significant. Unlike other ancient societies bound by tradition, Greece became a fertile ground for curiosity to expand unbounded, leading to the creation of both speculative thought and systematic reasoning.

Russell highlights that while the Greeks achieved much in the arts and literature, their intellectual strides are even more notable, especially with the rise of philosophical inquiry with figures like Thales in the 6th century B.C.

The Pre-Socratics emerge precisely when philosophy and science were “born together” with Thales’ famous eclipse prediction (585 B.C.), symbolizing the break from myth to explanation.

Geography, trade, coinage (from Lydia, before 700 B.C.), and alphabetic writing (via Phoenicians, with the critical addition of vowels) catalyzed a new civic and intellectual ecology.

Russell insists this can be explained “in scientific terms,” not by mystical “Greek genius.” The chapter’s thesis: structural conditions (commerce, the polis, contact with older cultures, and a flexible religion) created a culture where Pre-Socratic inquiry—cosmology, metaphysics, and rational debate—could flourish and become the seedbed for everything from Pythagorean mathematics to Athenian political thought.

Greek originality, then, is less a miracle and more a convergence of material conditions with a newly liberated intellectual temperament. “Philosophy begins with Thales” and with him a tradition of critical, naturalistic explanation.

Main points:

- “Philosophy begins with Thales… who predicted an eclipse in 585 B.C.” (birth of philosophy + science together).

- Writing invented in Egypt c. 4000 B.C.; alphabetic refinement via Phoenicians; Greeks added vowels.

- Coinage likely appears shortly before 700 B.C. (Lydia → Greek economy).

- Russell argues for scientific (not mystical) explanation of Greek ascent.

2. The Milesian School (Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes)

Chapter 2 History of Western Philosophy talks about the Milesian (Miletus was an ancient Greek city, was culturally the most important part of the Hellenic world) philosophers, Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, are the pioneers of Western philosophy, according to Russell.

The Milesian School inaugurates rational cosmology. Thales offers the first natural hypothesis—“everything is made of water”—and a method: bold conjecture with empirical orientation (e.g., eclipse cycles; elementary geometry tricks).

In regard to Thales Russell says, “In every history of philosophy for students, the first thing mentioned is that philosophy began with Thales, who said that everything is made of water. This is discouraging to the beginner, who is struggling—perhaps not very hard—to feel that respect for philosophy which the curriculum seems to expect. There is, however, ample reason to feel respect for Thales, though perhaps rather as a man of science than as a philosopher in the modern sense of the word.”

Anaximander goes more abstract: the apeiron (the indefinite) underwrites world-formation; life evolves from the moist; he speculates on maps, the shape of the earth, and astronomical sizes. Anaximenes shifts to air as the primary stuff, explaining change quantitatively by condensation/rarefaction (“soul is air”): a rudimentary physics connecting degrees of density to observed kinds.

Russell’s verdict: their significance lies less in correct answers than in asking good questions with explanatory ambition—stripped (for the most part) of mythic anthropomorphism. This is Pre-Socratic science before metaphysics hardens, fertile precisely because it is vigorous and revisable.

The Milesians’ cosmology links Ionia’s commerce, contact with Egypt and Babylonia, and a lightly held Olympian religion that allowed speculative freedom. Their quantitative bent sets up later Greek philosophy, mathematics, and eventually atomism.

Main points:

- Thales: eclipse (585 B.C.) and “water” as arche; “all things are full of gods” (proto-hylozoism).

- Anaximander: evolutionary hints (“man… descended from fishes”); sun 27–28× the earth (reports vary).

- Anaximenes: air; condensation/rarefaction theory; “Just as our soul, being air, holds us together…”

- Context: Ionia’s trade, Egypt/Babylonia ties, and pre-Darius cultural centrality.

3. Pythagoras (570 BC – 490 BC)

For Russell, Pythagoras fuses religion and mathematics into a paradigm that shaped European philosophy: the contemplative life gains prestige because mathematics seems certain, exact, and about reality—yet grasped by pure thought. Hence the slogan “all things are numbers” becomes a metaphysical program: order the world by ratio, harmony, and figure. The Pythagoreans’ discovery of the right-triangle theorem (3-4-5 → proof of a²+b²=c²) and their numeric theory of music seed the belief in a rational cosmos—the ancestor of the music of the spheres and later rationalist theology.

Pythagoras is often associated with the mystical and mathematical. He is best known for the Pythagorean theorem, but his influence goes beyond mathematics.

Russell emphasizes how Pythagoras and his followers linked mathematics and ethics. They believed in the immortality of the soul and that purification could be achieved through understanding mathematical harmony.

Pythagoras believed that the soul is an immortal thing, and that it is transformed into other kinds of living things; and, that whatever comes into existence is born again in the revolutions of a certain cycle, nothing being absolutely new; and that all things that are born with life in them ought to be treated as connected. Like St. Francis he is said to have had preached to animals.

Pythagorean (and Orphic) religion—transmigration, purity, initiation—casts philosophy as a way of life, not mere speculation.

Russell argues this blend of mathematics and mysticism dominates from Plato through Aquinas to Leibniz. The gain: standards of proof, structure, and aspiration to the eternal; the risk: downgrading sense in favor of intelligible forms. Still, Pre-Socratic intellectualism here reaches a new register where cosmology, ethics, and number interlock.

Main points:

- “All things are numbers” → numbers as shapes; arithmetic grounds physics/aesthetics.

- Mathematical music (harmonic means/progressions).

- Proof of Pythagorean theorem generality (beyond 3-4-5).

- Enduring synthesis: “The combination of mathematics and theology, which began with Pythagoras…” (Plato → Kant).

- Orphic legacy: “philosophy as a way of life.”

Notable figures: Pythagoras; Orphics; later heirs (Plato, Aquinas, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz).

4. Heraclitus (c. 500 BC)

Heraclitus, with his doctrine of change, proposed that the world is in a constant state of flux.

Heraclitus radicalizes Pre-Socratic metaphysics with two linked doctrines: (1) flux—“You cannot step twice into the same river,” “The sun is new every day”—and (2) the dialectic of opposites—“war is common to all… strife is justice.”

Behind change stands an ordering Fire (logos) and cosmic justice that prevents either pole from winning. Russell highlights how Heraclitus’ aphorisms anticipate later dialectics (Hegel) and modern physics’ dynamism.

The doctrine dissolves the search for anything wholly permanent in the sensible world, pushing philosophy toward questions of meaning, order, and measure amid change. Though his style is oracular, the program is philosophically sharp: explain stability as a dynamic balance, not a static substrate.

Russell also notes that what survives is largely via opponents (Plato, Aristotle), yet even through polemic Heraclitus appears “admirable”—proof of his depth. As a Pre-Socratic counter to Parmenides, Heraclitus makes cosmology historical and ethical (justice as measure) and turns philosophy into an analysis of tension, measure, and becoming.

Main points:

- Flux: “You cannot step twice into the same river… ‘The sun is new every day.’”

- Opposites: “war is common to all, and strife is justice.”

- Unity-in-opposition: “The way up and the way down is one and the same.”

- Fire as world-order: “ever-living Fire… with measures kindling and measures going out.”

Notable figures: Heraclitus (with later interlocutors Plato, Aristotle, Hegel).

5. Parmenides (c. 515 BC)

Parmenides is the Pre-Socratic arch-critic of flux. If Heraclitus says “everything changes,” Parmenides answers: nothing changes.

Sensible plurality and becoming are illusion; only the One, which is God, truly is—indivisible, without opposites, conceived as a perfect sphere, the same everywhere. Russell stresses that Parmenides pioneers a style of metaphysical argument grounded in logic—an ancestor of much later metaphysics (down to Hegel).

The poem distinguishes “the way of truth” (strict ontology) from “the way of opinion” (cosmological story fitted to appearances).

The upshot is a severe challenge: if being must be thinkable and non-contradictory, becoming collapses into not-being, which is unthinkable. This provokes successors (Empedocles, Anaxagoras, atomists) to reconcile physics with Eleatic logic—either by multiplying eternal elements, positing Nous, or introducing atoms and void.

Russell reads Parmenides as a decisive fork: he forces Greek philosophy to become self-conscious about logic, ontology, and the relation between thought and world.

Main points:

- Antithesis to Heraclitus: “Heraclitus maintained that everything changes: Parmenides retorted that nothing changes.”

- Ontology: “The only true being is ‘the One’… conceived as a sphere, without opposites.”

- Method: invents metaphysics based on logic (“way of truth” vs. “way of opinion”).

Notable figures: Parmenides; the Eleatics; Plato (strongly influenced).

6. Empedocles (c. 490 BC – 430 BC)

The mixture of philosophers, prophet and a man of science, Empedocles was a democratic politician and who claimed to be a god. Russell confirms the legend about Empedocles.

Empedocles welds Pre-Socratic science and metaphysics into a two-force cosmology: four everlasting “roots” (earth, air, fire, water) are mixed by Love and separated by Strife, cycling through phases of union and dissociation; compounds perish, only the elements and the two forces endure.

Russell stresses how this system tries to honor Eleatic logic (no creation/ex nihilo) while explaining motion and plurality—hence the famous world-sphere that alternately encloses Love or Strife before reversing again.

Alongside cosmology, Empedocles displays scientific bite: the air experiment (the clepsydra) treats air as a distinct substance; he notes centrifugal force (water in a swung cup) and sketches an early, if fanciful, evolutionary winnowing of forms where only certain assemblages survive. He also remarks that the moon shines by reflected light and that light’s travel time is real though imperceptible.

Religiously, he remains largely Orphic/Pythagorean (purification, transmigration), but Russell’s verdict is clear: Empedocles is most original in the four elements and the Love/Strife mechanics, an unusually “scientific” move among the Pre-Socratics.

Main points:

- “It was he… who established earth, air, fire, and water as the four elements… combined by Love and separated by Strife,” with alternating epochs.

- Cycle and sphere: Love within/Strife without, then the reverse; no final stasis.

- Air as a separate substance (clepsydra): “the bulk of the air inside… keeps [water] out.”

- Early evolution sketch: heads without necks, mis-matched limbs; only some forms survived.

- Astronomy: moon’s reflected light; light takes time; solar eclipses by the moon.

Notable figures: Empedocles; Orphics/Pythagoreans; Lucretius (poetic reception).

7. Athens in Relation to Culture

In this section of History of Western Philosophy, Russell discusses the cultural and intellectual environment of Athens, which became the epicenter of Greek philosophical thought.

Russell frames Athens’ cultural high-tide as a sharp crest after the Persian Wars (490; 480–79 B.C.): the Delian alliance’s finances created naval supremacy and wealth; Pericles then rebuilt the Acropolis—the Parthenon crowns a city that became “the most beautiful and splendid” in Hellas.

Figures like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides created timeless tragedies, while Aristophanes contributed his comic genius, critiquing the intellectual trends of the time, including Socrates. Athens, ravaged by Xerxes, saw its temples reconstructed under Pericles, making it the most beautiful city in the Hellenic world.

The Parthenon and other temples immortalized this period, representing the artistic and cultural zenith of Athens. This prosperity was accompanied by intellectual growth, as seen in the works of Herodotus, who chronicled the Persian Wars from an Athenian perspective.

This golden age was short-lived, however.

Despite its flourishing art and architecture, the internal tensions between democracy and aristocracy, and external conflicts with Sparta, foreshadowed a darker period for Athens. The Peloponnesian War, fueled by Athenian imperialism and economic prosperity, led to the eventual defeat of Athens.

Although politically weakened, Athens’ intellectual legacy endured. The philosophical achievements of Socrates, Plato, and later Aristotle made Athens the philosophical capital of the world for nearly a millennium. The Academy, founded by Plato, continued to be an intellectual center even as Alexandria eclipsed Athens in mathematics and science.

What I find most poignant in this narrative is the fleeting nature of Athens’ golden age—how victory and prosperity led to a flourishing of culture, yet at the same time sowed the seeds of its downfall. The philosophical supremacy of Athens remained, even as political power waned, and it is this enduring intellectual legacy that resonates.

Despite its eventual political collapse, Athens became a beacon of philosophy, influencing Western thought long after its empire faded. The closure of the Academy in A.D. 529, under Justinian’s religious rule, marked the symbolic end of classical Athens, leading to the Dark Ages, but its intellectual spirit survived, awaiting its reawakening in the Renaissance.

In population terms, the peak is strikingly small—≈230,000 (including slaves) around 430 B.C.—making the artistic output even more astonishing; indeed, “the achievements of Athens in the time of Pericles are perhaps the most astonishing thing in all history.” Tragedy (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides), comedy (Aristophanes), sculpture (Pheidias), and history (Herodotus) define the age.

Philosophically, Athens imports Anaxagoras (nous-cosmology) and later hosts Socrates, though Russell notes the city’s excellence here was “artistic rather than intellectual” in this century.

The Peloponnesian War (from 431) brings plague, the Sicilian disaster (414), the Thirty Tyrants (404), and, under a resentful restored democracy, Socrates’ trial (399 BC.)—closing a brilliant but precarious chapter of Greek civilization, politics, and philosophy.

Main points:

- From alliance to Athenian Empire via payments/ships; Pericles’ 30-year leadership.

- Parthenon and other temples rebuilt; Pheidias commissioned.

- Population ≈230,000 at peak (c. 430 B.C.).

- Cultural roster: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Herodotus.

- War, plague, Sicilian expedition, Thirty Tyrants, Socrates’ trial (399).

Notable figures: Pericles; Pheidias; Aeschylus; Sophocles; Euripides; Aristophanes; Herodotus; Socrates.

8. Anaxagoras (c. 500 – c. 428 BC)

This chapter of History of Western Philosophy is dedicated to Anaxagoras.

An Ionian transplanted to Athens, Anaxagoras exemplifies rational cosmology within Greek civilization: he posits that “everything is infinitely divisible” and that each thing contains “a portion of everything,” so what appears as fire or flesh simply preponderates in that mixture.

He denies the void via experiments (clepsydra; inflated skin), and introduces Mind (Nous) as an independent, unmixed, infinite ordering cause that sets the cosmos rotating—light things moving outward, heavy things inward.

Culturally, he becomes entangled with Athenian politics: imported (likely) by Pericles, lampooned by opponents, and prosecuted under a law against impiety for saying the sun is a red-hot stone and the moon is earth; he leaves Athens and founds a school back in Ionia.

Russell also notes characteristic provocations—e.g., that “snow is black (in part).” Overall, Anaxagoras shifts Pre-Socratic philosophy toward explanation by Mind while keeping a broadly naturalistic physics—an important bridge between Milesian materialism and later metaphysics.

Main points:

- “Mind has power over all things that have life; it is infinite and self-ruled, and is mixed with nothing.”

- Cosmic rotation sorts heavy/light; no void (clepsydra, inflated skin).

- Prosecution for teaching “the sun was a red-hot stone” and the moon was earth.

- Epistemic sting: “snow is black (in part).”

Notable figures: Anaxagoras; Pericles; Aspasia; (echoes in) Socrates, Euripides.

9. The Atomists (Leucippus & Democritus)

Chapter IX of Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy delves into the ideas of Leucippus and Democritus, the founders of atomism that proposed that the universe consists of indivisible particles (atoms) moving in a void.

Atomism, as they conceptualized it, was a revolutionary attempt to explain the nature of the universe in terms of indivisible particles, or atoms, and the void through which these atoms moved.

Their theories offered a mechanistic, rather than teleological, explanation of natural phenomena, rejecting the need for purpose or final causes in understanding the cosmos.

What strikes me immediately is Russell’s observation that Leucippus, the less-known founder of atomism, is often overshadowed by Democritus. The two philosophers are difficult to disentangle because their works were so intertwined, with many of Leucippus’ ideas later attributed to Democritus.

Leucippus and Democritus deliver the most durable Pre-Socratic metaphysics: atoms and the void.

Atoms are indestructible, physically (not geometrically) indivisible, of infinitely many kinds (shapes/sizes), always in motion in infinite space. Against teleology, they give mechanistic accounts: vortices form by collisions; worlds emerge and perish without purpose. On first motion, Russell sides with those who read the Atomists as positing random motion (kinetic-theory-like), not unequal “falling”: in an infinite void there is “neither up nor down.”

Ethically and methodologically, they are strict determinists: “Naught happens for nothing, but everything from a ground and of necessity.”

Russell’s assessment is generous: the atomists’ world is closest to modern science among the ancients, not least for its refusal of final causes; and Democritus pushes a proto-critical stance on the deceptiveness of the senses versus explanatory structure. In short, atomism anchors Greek cosmology and later physics while sharpening debates about being, causation, and knowledge within philosophy.

Main points:

- Atoms + void; infinite kinds; always in motion.

- Random motion in the void; “neither up nor down”; vortices form mechanically.

- Determinism: “Naught happens for nothing…” (Leucippus).

- Method: preference for mechanistic over teleological explanation.

Notable figures: Leucippus; Democritus; (later) Epicurus; Aristotle (critic).

10. Protagoras (c. 500 B.C)

Russell presents Protagoras, chief Sophist, as the pivotal sceptic of Greek philosophy: famous for “Man is the measure of all things”, he relocates truth to appearance and convention, dissolving objective standards when perceptions conflict.

His book On the Gods opens disarmingly—“With regard to the gods, I cannot feel sure either that they are or that they are not…”—capturing a practical agnosticism. Biographically, he’s born c. 500 B.C. at Abdera, visits Athens twice (second ≤ 432 B.C.), and drafts laws for Thurii (444–3 B.C.).

Philosophically, Plato’s Theaetetus pushes an interpretation aligned with later pragmatism (F. C. S. Schiller): some opinions are better for health or action though none is truer in an absolute sense.

Politically and ethically, Protagoras’ relativism inclines him to defend law, convention, and worship, since, in a world without objective truth, the majority effectively arbiters belief and order. In Russell’s story of Greek civilization and Pre-Socratic debate, Protagoras turns inquiry toward epistemology, rhetoric, and civic practice.

Main points:

- “Man is the measure of all things…” (truth as appearance).

- On the Gods: “I cannot feel sure either that they are or that they are not…”.

- Athenian visits (≤ 432 B.C.); Thurii law code (444–3 B.C.).

- Pragmatist reading (Schiller); better vs truer opinions (jaundice example).

- Defence of law & convention despite scepticism.

Notable figures: Protagoras; Plato (dialogues Protagoras, Theaetetus); F. C. S. Schiller.

Part II

11. Socrates (c. 470 BCE – 399 BC)

Concerning Socrates, Russell in his History of Western Philosophy writes “Socrates is a very difficult subject for the historian, and there are many men concerning whom it is certain that very little is known, and other men concerning whom it is certain that a great deal is known; but in the case of Socrates the uncertainty is as to whether we know very little or a great deal.

Socrates, as Bertrand Russell portrays, emerges not just as a philosopher but as a profound enigma of intellectual history. Socrates is portrayed as is one of the most enigmatic and influential figures in Western thought in A History of Western Philosophy. What makes Socrates particularly difficult for historians, as Russell points out, is that much of what we know about him comes from two of his students: Plato and Xenophon.

These two accounts differ significantly, leading to debates about how much of the historical Socrates we truly know.

Russell frames Socrates as a historical riddle: we know the bare facts—Athenian citizen, public disputant, executed in 399 B.C. at about 70—but beyond that we’re caught between Xenophon’s pious traditionalist and Plato’s penetrating ironist.

Russell refuses to “take sides,” extracting instead the common core: a moral and civic inquirer whose method—short, pointed questions—exposed contradictions in everyday political and ethical talk. Against the background of Athenian volatility (democracy, the Thirty Tyrants, and war), Socrates’ insistence on competence in public office and personal integrity looked simultaneously subversive and patriotic.

Russell’s philosophy here is method: a dialectic that clarifies concepts rather than discovers new empirical facts. The portrait is deliberately anti-romantic: Socrates is made less a saint than a citizen-philosopher whose ethics, politics, and knowledge claims are inseparable from the life of the polis.

In short, Socrates inaugurates a new model of intellectual responsibility—one that grounds ideas in public argument while provoking the anxieties of a city at war with itself.

Main points:

- Minimal certainties; competing witnesses (Plato vs. Xenophon).

- Method: argumentative questioning about civic competence and justice.

- Political context: oligarchy/democracy whiplash culminating in the trial.

Notable figures: Xenophon; Plato; Aristophanes; Critias (of the Thirty).

12. The Influence of Sparta

To decode Plato’s politics, Russell says, study Sparta—both the reality (military efficiency, harsh discipline) and the myth (Plutarch’s Lycurgus), which seduced later political ideas from Rousseau to Nietzsche and even National Socialism.

The reality humbled Athens; the myth shaped utopian longings for order, unity, and elite rule. Russell’s core claim: the “myth of Sparta,” more than Sparta itself, colonized the Western imagination, blending ethics with authoritarian politics and packaging power as virtue. This myth fed Plato’s philosopher-guardian ideal and kept resurfacing whenever intellectuals dreamed of rational rule without democratic messiness.

The historical statistics here are spare but telling: Sparta’s victory in the Peloponnesian War and its later decadence versus enduring prestige in literature.

The philosophical upshot is a caution: ideas about politics often travel through stories, not data, and myths can outlive facts. In Russell’s view, the import isn’t institutional minutiae but how “Sparta” became a keyword in the West for stern simplicity, unity, and civic ethics, thereby steering political philosophy toward anti-democratic “solutions.”

Main points:

- Double effect: reality (military success) vs. myth (normative ideal).

- Plutarch’s Lycurgus fixes the legend; its influence persists across centuries.

- The myth nourishes authoritarian readings of ethics and politics.

Notable figures: Lycurgus (as myth); Plutarch; Rousseau; Nietzsche.

13) The Sources of Plato’s Opinions

Russell’s analysis of Plato’s intellectual lineage is a testament to the intricate tapestry of influences that shaped his philosophy. Russell states that Plato’s ideas are derived from Pythagoras, Parmenides, Heraclitus and Socrates.

Russell situates Plato biographically (born 428–7 B.C.), socially (aristocratic links to the Thirty Tyrants), and emotionally (the democratic execution of Socrates). Unsurprisingly, Plato looked to Sparta for an outline of order, while translating metaphysical ideas into politics.

Philosophically, Russell lists four pillars: Pythagoras (mysticism, mathematics, immortality), Parmenides (timeless Being), Heraclitus (flux in the sensible), and Socrates (ethical focus, teleology). The synthesis is powerful: sensory change cannot yield knowledge; therefore, universals and mathematical structures guide the soul; therefore, well-formed ethics and politics must be designed by intellect, not appetite.

Russell’s tone is sceptical—he aims to “treat [Plato] with as little reverence as if he were… an advocate of totalitarianism”—but the genealogy stands: Plato’s theory of ideas, ethics, and civic utopia crystallize from these sources. The statistics here mark dates and social facts (428–7; the Thirty; post-war Athens), which Russell treats as causal pressures on political philosophy. The chapter is a reminder that metaphysics is never far from the city gates.

Main points:

- Biographical triggers for anti-democratic leanings (war, the Thirty, Socrates’ death).

- Four sources: Pythagoras, Parmenides, Heraclitus, Socrates—yield ideas, knowledge, ethics.

- Russell’s interpretive stance is deliberately deflationary.

Notable figures: Pythagoras; Parmenides; Heraclitus; Socrates; the Thirty Tyrants.

Plato was “born in 428–7 B.C.… related to [the] Thirty Tyrants… [and] turned to Sparta for an adumbration of his ideal commonwealth.”

14. Plato’s Utopia (Republic)

The Republic is a three-part construction: (1) the ideal State (to near end of Book V), (2) the definition of the philosopher (Books VI–VII), and (3) analysis of actual constitutions.

Justice is sought “in the large,” then read back into the soul. Citizens fall into three classes—producers, soldiers, guardians—with political power strictly reserved for the last. Education (music/culture and gymnastics) produces harmony; philosopher-kings govern because knowledge of the Good aligns ethics with politics.

The radical—and chilling—social program follows: communism of women and children, State-arranged festivals, eugenic pairings to keep population constant, age windows (mothers 20–40, fathers 25–55), compulsory abortion/infanticide for unsanctioned births.

Russell reads this as the Spartan myth in philosophical dress: order purchased by erasing private ties, with poetry censored and sentiment domesticated for civic ends. Powerful ideas, yes—but also a template for authoritarian politics masquerading as ethics.

Main points:

- Structure and purpose: justice via the State’s macro-design.

- Class division; guardians’ monopoly on power; education as formation.

- Family/sexual regulation and demographic policy, with numeric thresholds.

Notable figures: Socrates (speaker); guardians/soldiers/commoners; poet-legislator as censor.

“Friends… should have all things in common, including women and children.”

15. The Theory of Ideas

For Russell, Plato’s Ideas (Forms) are a first, flawed but epoch-making attempt to tackle universals—the backbone of knowledge beyond shifting perception.

The minimum that “remains,” even after critique, is linguistic: we cannot speak wholly in proper names; general terms (“man,” “similar,” “before”) must have meaning, which pushes us toward ideas. Still, Russell argues Plato “has no understanding of philosophical syntax,” treating universals like superior particulars (“beauty is beautiful”), and thereby eliding the gap between adjectives and things.

The Parmenides already self-criticizes the theory; later, Aristotle will formalize the objections (e.g., the “third man”). Russell’s verdict is balanced: beginnings are “crude,” but Plato put the real problem—universals—on the table, anchoring later ethics, science, and logic. In effect, knowledge must say something general; the metaphysics of ideas is a pioneering (if awkward) scaffold that made later precision possible.

Main points:

- Irreducibility of general terms to proper names; case for universals.

- Syntax mistake: treating universals as things; early self-critique in Parmenides.

- Lasting achievement: posing the universals problem for later logic and science.

Notable figures: Parmenides; Socrates (as discussant); Aristotle (later critic).

“We cannot express ourselves in a language composed wholly of proper names… [there is] a prima facie case in favour of universals.”

16. Plato’s Theory of Immortality

Plato’s arguments for the soul’s immortality, as Russell delineates, are both intricate and deeply moving. The dialogue Phaedo offers a vision of death as a liberation of the soul, a perspective that has profoundly influenced religious and philosophical thought. Russell’s skepticism—that these arguments often rely more on faith than reason—invites me to confront my own beliefs about mortality.

Russell treats Phaedo as both an ethical drama and a doctrinal brief: Socrates’ serenity is inseparable from doctrines about immortality, reincarnation, and the soul’s kinship with ideas.

The dialogue’s argumentative spine runs through the cyclical argument (from opposites), the recollection (anamnesis) proof, and the affinity argument that aligns the rational soul with the invisible and changeless. It also records Socrates’ replies to the harmony objection (the soul cannot be a mere tuning of bodily parts, since harmony does not pre-exist its instrument) and closes with the vivid myth of postmortem fates—“the good go to heaven, the bad to hell, the intermediate to purgatory.”

Russell underscores the cultural reach: “What the gospel account of the Passion and the Crucifixion was for Christians, the Phaedo was for pagan or free-thinking philosophers.” Yet his verdict is tart: Socrates’ courage is less striking because he expects bliss, and the reasoning too often aims to make the universe match ethics.

The famous last line—“Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius”—seals the stance that death is a cure, not a catastrophe.

Main points:

- Arguments for immortality: recollection, opposites, affinity; reply to the “soul-as-harmony.”

- Cultural weight of Phaedo for later philosophy and theology.

- Ethical portrait and last words: “Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius…”.

Notable figures: Socrates; Simmias & Cebes; St. Paul and the Fathers (reception).

Russell on the saint–philosopher split: “There is something smug and unctuous about him… determined to prove the universe agreeable to his ethical standards.”

17. Plato’s Cosmogony

Russell’s discussion of Plato’s cosmology in Timaeus reveals a philosopher grappling with the origins of the universe through reason and myth. The concept of a Demiurge, crafting order from chaos, reflects Plato’s attempt to reconcile the material and the ideal.

In Timaeus, cosmogony becomes moralized cosmology: a benevolent craftsman-God imposes order on pre-existent disorder, modeling the world on eternal archetypes. “God desired that all things should be good, and nothing bad, as far as possible… out of disorder he brought order.”

The result is a single living world-animal, spherical and self-moving in perfect circle; time and space appear as cosmic “copies,” with the four elements held in proportional harmony and (in Russell’s précis) correlated with regular solids.

Russell thinks this is philosophically weak but historically immense—number and purpose are imported from Pythagorean doctrine, and the dialogue shaped Hellenistic and medieval metaphysics precisely because of its teleology: a world made “to be as like [God] as possible.”

He grants that Plato seriously believes the account of creation as order from chaos, the proportion of elements, and the copy-relation to eternal patterns; and he notes the Greek blend of necessity with final cause that conveniently evades a Christian-style problem of evil. The ideas are grander than the physics, but the philosophy of Timaeus mattered by the sheer force of its integrative myth.

Main points:

- World as living animal; one cosmos; sphere; perfect rotation.

- “God desired that all things should be good…” and “out of disorder he brought order.”

- Number, proportion, and the four elements; Pythagorean inheritance.

Notable figures: Timaeus (speaker); Pythagoreans; Cicero; Neoplatonists (reception).

Russell: the dialogue is “to be studied because of its great influence… not confined to what is least fantastic.”

18. Knowledge and Perception in Plato

Against the modern drift toward empiricism, Russell presents Plato’s case that knowledge belongs to concepts rather than perceptions.

In the Theaetetus, “knowledge is nothing but perception” is proposed, then tested to destruction by tying it to Protagoras (“man is the measure”) and Heraclitus (universal flux). If what seems to me is true-for-me, and all sensible things are in becoming, truth dissolves into shifting sensations.

Plato, accordingly, stresses the comparative certainty of “2 + 2 = 4” over “snow is white,” nudging us toward ideas and their logical articulation. Russell is clear that the dialogue ends in aporia—no final definition—yet he finds in Plato the enduring insight that philosophy needs stable universals for science, logic, and ethics to be possible.

Thus the chapter maps how perception falls short, how relativism is self-defeating, and why the path to knowledge runs through things like number, sameness, and difference rather than the eye’s momentary report.

Main points:

- Theaetetus’ thesis: “knowledge is nothing but perception.”

- Tie-ins: Protagoras (relativism) and Heraclitus (flux).

- “2 + 2 = 4” as model of certain knowledge vs. “snow is white.”

Notable figures: Theaetetus; Socrates; Protagoras; Heraclitus.

“There is nothing worthy to be called ‘knowledge’ to be derived from the senses.”

19. Aristotle’s Metaphysics

Russell reads Aristotle’s metaphysics as a biological teleology: form and matter relate by potentiality and actuality; change is the gaining of form; the most actual being is God, “pure form and pure actuality,” hence changeless.

Explanation turns on the four causes—material, formal, efficient, final—with the “unmoved mover” functioning primarily as final cause, the object of desire that draws things to completion. Astronomical theory pushes Aristotle to multiply movers: there are “either forty-seven or fifty-five unmoved movers,” a number Russell relishes as a stress-test for later theology.

God’s nature is contemplative—“its thinking is a thinking on thinking”—and thus not providential in a Christian sense. A critical strand (via Zeller) notes ambiguities in hylomorphism and the apparent “hypostatizing” of forms. Russell admires the system’s reach while calling out potentiality as a too-convenient placeholder that often “conceals confusion of thought.”

Still, the architectonics—ideas domesticated into form, knowledge keyed to essence, ethics nested in teleology—set the long agenda for medieval philosophy, logic, and science.

Main points:

- Four causes; change as actualization of potential.

- God as final cause; “thinking on thinking”; non-providential.

- 47 or 55 unmoved movers (astronomical).

- Russell’s critique of potentiality; Zeller on forms.

Notable figures: Aristotle; Zeller (critic); Averroes & Dante (later debates on immortality).

“God produces motion by being loved… every other cause… works by being itself in motion.”

20) Aristotle’s Ethics

Russell calls the Nicomachean Ethics the summation of “educated and experienced” opinion—firmly civic, cool on mysticism, wary of utopian politics. The good is happiness, “an activity of the soul,” and the soul divides into rational and irrational parts, yielding intellectual and moral virtues.

Virtue is a cultivated habit (hexis) aiming at the mean relative to us; thus the legislator’s job is to make citizens good by habituation. Russell’s tone is unsentimental: the book “appeals to the respectable middle-aged” and often repels the ardent. Yet its systematic clarity—on character, practical reason, temperance, justice—fed later ethics and political philosophy. In the background, a thin metaphysics persists: reason is “purely contemplative” without appetite; action needs the alloy.

For Russell, this is both the strength (civic sobriety) and the limitation (narrow affect). Still, the project frames philosophy as education in virtue rather than speculation—a legacy as durable as any in metaphysics or logic.

Main points:

- “The good… is happiness, which is an activity of the soul.”

- Two parts of the soul ⇒ intellectual/moral virtues; reason needs appetite for action.

- Habituation and the role of the legislator in shaping ethics.

- Russell’s appraisal: middle-aged respectability vs. youthful ardor.

Notable figures: Aristotle; the “legislator”; later readers since the 17th c. (reception).

21. Aristotle’s Politics

Russell reads the Politics as a brilliant snapshot of Greek city-state assumptions and party conflicts, yet one that now feels parochial. Aristotle theorizes the State as a natural organism aimed at “the good life,” not mere security or trade; hence “a political society exists for the sake of noble actions” and the State is “the union of families and villages in a perfect and self-sufficing life.”

He begins from household relations (husband–wife, master–slave), deeming slavery “natural,” a claim Russell highlights—and rebukes—by quoting Aristotle’s own just-war rationale for enslavement.

The treatise anatomizes constitutions by ethical aim rather than form, distinguishing good (monarchy, aristocracy, polity) from bad (tyranny, oligarchy, democracy) and defending a mixed “polity” as a practical mean. He offers concrete, if chilling, social prescriptions: working men should not be citizens; citizens should own property; husbandmen should be slaves “of a different race”; Greeks alone combine spirit and intelligence.

Russell also relishes Aristotle’s incidental details—the “right age for marriage is thirty-seven in men, eighteen in women”—as revealing the complacent aristocratic ethos. Education closes the book: cultivate virtue, not utility; teach drawing and music for moral taste, not professional skill.

Main points:

- State as organism & telos: “The end of the State is the good life…”; law is possible only within the State.

- Household as basis; slavery “natural”: master–slave relations are foundational; war can “justify” enslavement—an ethical faultline.

- Regime taxonomy by ethical aim: good (monarchy, aristocracy, polity) vs. bad (tyranny, oligarchy, democracy); mixed forms common.

- Qualified case for democracy: because most actual governments are bad, democracy often proves least bad in practice.

- Civic exclusions & race theory: workers excluded from citizenship; slaves of “southern races”; Greeks, uniquely, “spirited and intelligent.”

- Education program: virtue over utility; literacy is necessary but insufficient; athletic moderation; aesthetic formation.

- Statistical figures: marriage ages 37 (men) and 18 (women).

Notable figures: Aristotle; Euripides (anecdote); Thales (olive-press monopoly anecdote).

22 . Aristotle’s Logic

Russell’s verdict is sharp: Aristotle’s supremacy in logic endured through late antiquity and the Middle Ages, but this legacy “is as definitely antiquated as Ptolemaic astronomy.” The genuine advance was the codification of the syllogism—major premise, minor premise, conclusion—organized into figures and moods, with the famous first-figure set Barbara, Celarent, Darii, Ferio.

Yet Russell stresses limitations that froze inquiry: failure to distinguish equivalent forms in “Barbara,” illicit conversions, and a semantics anchored to subject–predicate “substance.” , In a stinging summation, he calls the doctrinal core “wholly false,” except for the formal theory of the syllogism—and even that is “unimportant” for modern logic.

For Russell, two millennia of scholastic adherence turned a historical milestone into a cul-de-sac: “practically every advance… has had to be made in the teeth of opposition from Aristotle’s disciples.”

Main points:

- Enduring authority, outdated system: prestige of Aristotelian logic overshadowed its obsolescence.

- Syllogistic architecture: three figures (schoolmen add a fourth); canonical moods Barbara, Celarent, Darii, Ferio.

- Formal vs. material insight: tidy deduction but poor apparatus for mathematics, science, and relational logic. (Russell’s critique summarized from the chapter’s argument.)

- Philosophical mistake of “substance”: grammar projected onto ontology.

- Historical consequence: over 2,000 years of stagnation in logic’s mainstream reception.

Notable figures: Aristotle; the medieval schoolmen who codified a fourth figure and preserved the tradition.

23. Aristotle’s Physics

Russell, in his A History of Western Philosophy examines Physics and On the Heavens—immensely influential yet, he says, containing “hardly a sentence… [that] can be accepted in the light of modern science.”

Aristotle’s world is teleological and two-story: below the moon, changeable bodies of four elements (earth, water, air, fire) move rectilinearly by nature; above, eternal bodies composed of a fifth element (quintessence) move in perfect circles, attached to spheres.

The theory explains weight, lightness, and “natural place,” but founders on comets, projectiles, and planetary motion. Galileo’s parabolic trajectory, and later Newton’s First Law (uniform straight-line motion absent external force), overturn the Aristotelian picture in which circular motion is “natural” and needs no sustaining force.

Finally, the incorruptibility of the heavens yields to stellar birth and death: suns explode or “die of cold”—nothing visible escapes change. Russell also sketches the imaginative background: a living, animal-like cosmos that seduced reason into vitalistic explanations.

Main points:

- Two regions, five elements: sublunary four elements vs. heavenly quintessence; rectilinear vs. circular “natural” motion.

- Projectiles & parabolas: Galileo refutes the “break then fall” model; parabolic motion replaces it.

- Newton vs. Aristotle: First Law makes circular motion require centripetal force—reversal of natural-motion doctrine.

- Heavenly change: stars are born and perish—against incorruptibility.

- Russell’s verdict: the books shaped science for centuries, yet are now scientifically untenable.

Notable figures: Aristotle; Galileo; Newton; Dante (poetic afterlife of the spheres imagery).

24. Early Greek Mathematics and Astronomy

For Russell, Greek achievement in mathematics and astronomy is uncontested: “what they accomplished in geometry is wholly beyond question,” and the very art of proof is “almost wholly Greek in origin.” ,

He threads stories (Thales measuring a pyramid by equal-shadow length; the cube-duplication problem) to show how practice sparked theory, then turns to rigor: irrationals (√2) among the early Pythagoreans; Eudoxus’s proportion theory; and Euclid’s Elements—a tour de force of organization and axiomatics whose parallel-postulate strategy shows both rigor and the dubiety of assumptions. , Euclid’s cultural journey (Arabic transmission, Latin in 1120) illustrates a millennium-long arc from pure theory to later utility when Galileo and Kepler made parabolas and ellipses central to ballistics and planetary orbits.

Astronomy yields striking numbers: Eratosthenes’ earth diameter 7,850 miles (≈50 short); Ptolemy’s lunar distance 29½ Earth diameters (true ≈30.2); ancient solar distances ranging from 180 to 6,545 Earth diameters (true ≈11,726).

Russell credits Aristarchus with the heliocentric hypothesis (Seleucus adopted it), while Hipparchus—“the greatest astronomer of antiquity”—built precise star catalogs (~850 stars) and trigonometry, shaping the geocentric, epicyclic tradition later perfected by Ptolemy.

Main points:

- Origins of proof: Greek geometry creates demonstrative method; √2 and duplication of the cube drive theory.

- Euclid’s synthesis: structure, proportion (after Eudoxus), irrationals (Book X), regular solids; later non-Euclidean challenge. ,

- From pure to applied: conics become physics and astronomy tools in the 17th century.

- Astronomical numbers: Earth’s diameter (7,850 mi); lunar distance (29½ D⊕ ≈ 30.2); solar distance estimates (180/1,245/6,545 vs. 11,726).

- Heliocentrism & its eclipse: Aristarchus hypothesizes; Seleucus adopts; Hipparchus advances epicycles and catalogs ~850 stars.

Notable figures: Thales; Pythagoreans; Eudoxus; Euclid; Aristarchus; Seleucus; Hipparchus; Apollonius; Ptolemy; Eratosthenes. ,

Russell writes):

- “A political society exists for the sake of noble actions, not of mere companionship.”

- “Men who work for their living should not be admitted to citizenship.”

- “Aristotle’s most important work in logic is the doctrine of the syllogism.”

- “Hardly a sentence in either can be accepted in the light of modern science.”

- “The art of mathematical demonstration was, almost wholly, Greek in origin.”

Part III: Ancient Philosophy after Aristotle

25. The Hellenistic World

Russell’s through-line is that Alexander’s conquests (334–323 B.C.) dissolved the self-reliant polis and ushered in a cosmopolitan, expert-run world whose mood swung from scientific brilliance to private anxiety.

He notes that “three battles destroyed the Persian Empire,” opening a Greek-speaking zone from Egypt to Bactria; politics became the business of Macedonian armies and courtiers, not citizens.

In that setting, Alexandria is the showpiece: Ptolemaic patronage, the Library, and a cluster of third-century mathematicians (Euclid, Archimedes, Aristarchus, Apollonius, Eratosthenes) represent a decisive turn to specialization—“there were soldiers, administrators, physicians, mathematicians, philosophers, but there was no one who was all these at once.”

Meanwhile, religious imagination tilted toward astrology and “fate,” a fashion that Russell (following Gilbert Murray) calls a “new disease” of the age.

The result was intellectual advance paired with moral precariousness—respectable civic virtues atrophied amid uncertainty and fortune’s swings—preparing the ground for therapeutic philosophies (Epicureanism, Stoicism, Scepticism).

Main points:

- Alexander’s victories reorder the map; city-state politics become “parochial and unimportant.”

- Alexandria’s Library and sciences dominate late 3rd-century B.C. learning.

- Specialization replaces the old all-round citizen-sage.

- Astrology/magic spread; belief in fate grows.

- Moral corrosion in an age of instability.

Notable figures: Alexander; Ptolemies; Euclid, Archimedes, Aristarchus, Apollonius, Eratosthenes; Berosus.

26. Cynics and Sceptics

Cynicism (Antisthenes → Diogenes) radicalizes Socratic moral independence into a return to nature: no property, no convention, virtue through hard simplicity.

Diogenes aimed to “deface all the coinage”—to strip false social valuations—living like a “cynic” (dog) and preaching freedom from desire; “be indifferent to the goods that fortune has to bestow, and you will be emancipated from fear.”

Popular Cynicism later softened into convenient sermons in Alexandria (early 3rd c. B.C.). Scepticism (Pyrrho, then Timon) is Russell’s other thread: a school of dogmatic doubt—“nobody knows, and nobody ever can know.”

Timon’s regress argument (all deduction needs self-evident starting points, which can’t be found) undercuts Aristotelian foundations; yet ancient Sceptics still trusted phenomena (“That honey is sweet I refuse to assert; that it appears sweet, I fully grant”).

After Pyrrho’s and Timon’s deaths (275 and 235 B.C.), Arcesilaus turns the Academy skeptical. The upshot is a therapeutic ethos: Cynicism feeds Stoic ethics; Scepticism offers balm against worry in a disputatious age.

Main points:

- Antisthenes’ program: “no government, no private property, no marriage, no established religion.”

- Diogenes: virtue via indifference to fortune; anti-Promethean civilization critique.

- Popular Cynicism in early 3rd c. B.C. Alexandria.

- Scepticism defined as “dogmatic doubt.”

- Timon’s regress: proof becomes circular or infinite.

Notable figures: Antisthenes; Diogenes; Teles; Pyrrho (d. 275 B.C.); Timon (d. 235 B.C.); Arcesilaus (d. ~240 B.C.).

27. The Epicureans (342–270 BC)

A History of Western Philosophy treats Epicurus (342/1–270/1 B.C.) as a humane therapist who identifies the highest good with pleasure, understood soberly as the absence of pain and mental disturbance: “the best life is that in which pain is least.”

He founded his school in 311 B.C., lived simply, denounced political ambition and romantic entanglements, and prized friendship and study; his Atomist physics rejected teleology and freed disciples from fear of gods and death.

The portrait includes telling details: on dying (270/1 B.C.) he bequeathed his estate to Hermarchus and left 220 drachmas for yearly memorials—ritualizing philosophical community.

Russell links the Roman reception chiefly through Lucretius (99–55 B.C.), whose poem preserves Epicurean cosmology and ethics. He also notes Epicurus’s chilliness toward art and passionate love, and his counsel of quietism: the wise may “enjoy scientifically” what they cannot “enjoy emotionally.”

Overall, Epicureanism is a Hellenistic world antidote to anxiety: cultivate modest bodily needs, stable friendships, and undisturbed thought.

Main points:

- Pleasure = freedom from pain and fear; quiet life in a “Garden.”

- Founded 311 B.C.; died 270/1 B.C.; estate to Hermarchus; 220 drachmas to disciples.

- Reservations about art, marriage, sexual love.

- Roman channel: Lucretius (99–55 B.C.).

Notable figures: Epicurus; Hermarchus; Lucretius.

28. Stoicism

Stoicism absorbs Cynic hardiness and gives it a cosmopolitan, law-of-nature backbone: virtue is the only good; live “according to nature”; accept fate; all rational beings share one city.

Russell emphasizes its extraordinary social appeal—Murray even thought “nearly all the successors of Alexander professed themselves Stoics.”

In the Roman world, Stoicism becomes an ethical civil religion; by the first and second centuries A.D. there was, he writes, a school “virtually the same as Christianity in all except the miraculous.” Its scientific side (especially in Posidonius) also mattered: the Stoic estimate of Earth’s size (≈70,000 stades) helped Columbus imagine a westward route—“just by luck he found America.”

Ethically, Stoicism teaches resilience (apatheia), duty, and universal brotherhood; politically, it seeds ideas of natural law and equality that later feed Roman jurisprudence and beyond. It is the Hellenistic world’s sternest answer to instability: inner freedom under cosmic necessity.

Main points:

- Virtue alone is good; live by nature’s rational order (logos). (Overview from ch. 28.)

- Broad cultural uptake from Hellenistic monarchs to Roman elites.

- Near-Christian moral convergence in 1st–2nd c. A.D.

- Posidonius’s earth-size (70,000 stades) → Columbus’s gamble.

Notable figures: Zeno; Cleanthes; Chrysippus; Panaetius; Posidonius; Seneca; Epictetus; Marcus Aurelius. (Ch. 28 passim; see also 31:0.)

29. The Roman Empire in Relation to Culture

Russell sizes up Rome as an administrative colossus with a divided soul: efficient order and law coexisted with a “fever of blood-lust” in the arena.

At its height the empire held ~130 million people across over three million square miles—scale that stabilized trade, travel, and education, yet often flattened the brilliance of the Greek polis into prudent utility. The Roman spirit is “practical and unphilosophical”; philosophy turns inward to ethics and consolation, while literature oscillates between Augustan polish and imperial bombast.

The cosmopolitan reach spreads Greek schools (especially Stoicism and Epicureanism), but the civic engagement that birthed classical thought rarely returns. Russell’s balance sheet: Rome secures the Hellenistic world’s gains (roads, law, administration) and prepares channels for later Christian and medieval culture, even as it drains the old city-state’s oxygen that once fed speculative philosophy.

Main points:

- Sheer scale: ~130 M people; >3 M sq. miles.

- Spectacle and cruelty alongside order (“fever of blood-lust”).

- Ethically focused philosophy; diminished speculative ambition.

Notable figures: Augustus; later emperors; Seneca; Pliny; Marcus Aurelius. (Ch. 29 passim.)

30. Plotinus (A.D. 204–270)

For Russell, Plotinus (A.D. 204–270) is the Hellenistic world’s metaphysical capstone and a major ancestor of Christian Platonism. The system is a graded emanation: The One (beyond being and thought) overflows into Spirit/Nous (forms, intellect), which overflows into Soul (world-soul and individual souls).

Matter is the furthest attenuation, hence evil is “a defect, not a positive fact.” Salvation is an ascent: ethical purification, intellectual contemplation, and, at the summit, “a special knowledge… obtained by an illumination and an ineffable ecstasy.” Biographically, Plotinus studied at Alexandria and later taught in Rome; his pupil Porphyry edited 54 treatises into the Enneads, giving the most influential late-antique synthesis of Platonism.

Russell stresses both the grandeur and the distance from common reason: it is spiritualized metaphysics fit for an age seeking interior certainty—an answer to the Hellenistic craving for unity, meaning, and inward peace.

Main points:

- Triad: One → Nous → Soul; evil as privation.

- Knowledge culminates in ecstasy.

- Life and works: A.D. 204–270; 54 essays compiled by Porphyry as Enneads.

Notable figures: Plotinus; Porphyry.

Direct quotations used (sample highlights):

- Scepticism as “dogmatic doubt… ‘nobody knows, and nobody ever can know.’”

- Timon: “That honey is sweet I refuse to assert; that it appears sweet, I fully grant.”

- Diogenes: “be indifferent to the goods that fortune has to bestow.”

- Astrology “fell upon the Hellenistic mind as a new disease.”

- Plotinus: “special knowledge… by an illumination and an ineffable ecstasy.”

Book II: Catholic Philosophy

Part I: The Fathers

1. The Religious Development of the Jews

Russell’s through-line is that Christianity’s core grammar—sacred history, election, righteousness, law/creed, Messiah, and the Kingdom of Heaven—is inherited from late Judaism and then reinterpreted through Hellenistic categories.

He opens with the Jewish idea of a divinely guided story “beginning with the Creation, leading to a consummation in the future, and justifying the ways of God to man,” a frame Christianity universalizes (heaven/hell as final vindication) rather than abandons.

He itemizes six elements, including the elect (“the Chosen People” → “the elect”), practical righteousness (almsgiving), partial retention of the Law but with creed-like attachment to correct belief, the Messiah (future deliverer → historical Jesus identified with the Logos), and a concrete Kingdom of Heaven that promises everlasting bliss for the virtuous and everlasting torment for the wicked—contrasting sharply with Greek metaphysical other-worldliness.

He embeds this synthesis in brisk historical benchmarks—Ahab attested 853 B.C., Assyria’s conquest of the North in 722 B.C., Nineveh’s fall 606 B.C., and Judah’s catastrophe 586 B.C.—to show how trauma and dispersion forged apocalyptic hope and ethical intensity.

Main points:

- Six Jewish elements carried into Christianity: sacred history; election; righteousness (almsgiving); Law/Creed; Messiah; concrete Kingdom of Heaven.

- Christianity universalizes election yet retains a boundary of orthodoxy (“correct belief”).

- The Messiah shifts from future, worldly victory to a heavenly triumph through the historical Jesus, read via the Logos.

- The Kingdom of Heaven is temporal-future (reward/punishment), not Greek metaphysical timelessness—fueling popular appeal.

- Historical anchors: 853, 722, 606, 586 B.C.; Israel/Judah split; Assyrian and Babylonian shocks.

Notable figures: Prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah (Russell signals these sources and themes in his notes); Ahab as the first independently attested OT figure.

Russell encapsulates the moral psychology tersely: the future Other World “embodied revenge psychology” and was “intelligible to all and sundry.” —-A History of Western Philosophy

2) Christianity During the First Four Centuries

In A History of Western Philosophy, Russell narrates the early Church as a doctrinal crucible shaped by imperial politics and regional loyalties.

The decisive controversy is Arianism (Christian heresy that declared that Christ is not truly divine but a created being) versus Nicene orthodoxy: the Son’s relation to the Father had to avoid the twin perils of Arianism (too distinct) and Sabellianism, who unduly emphasized

the oneness of God and the Son (too identical).

“The doctrines of Arius were condemned by the Council of Nicæa (325) by an overwhelming majority,” but imperial favour oscillated;

Athanasius paid with repeated exile for his Nicene zeal. Geography mattered: Constantinople/Asia leaned Arian, Egypt was fanatically Athanasian, the West held to Nicaea—divides that eventually “impaired the unity of the Eastern Empire, and facilitated the Mohammedan conquest.”

The emperors (335–378) mostly favoured Arian positions; Julian (361–363) was pagan and neutral; Theodosius’s turn in 379 delivered complete Catholic victory—though an Arian century under Goths and Vandals followed, ended by Justinian, Lombards, and Franks.

Russell’s thesis: an embattled “orthodoxy” hardened creed and authority under pressure, setting the institutional pattern for medieval Christendom.

Main points:

- Doctrinal line-drawing: steering between Arianism and Sabellianism.

- Nicaea 325 condemns Arianism; Athanasius exiled repeatedly for orthodoxy.

- Regional “theologies”: Egypt pro-Athanasius; Asia/Constantinople Arian; West Nicene.

- Political timeline: 335–378 Arian-leaning emperors; 361–363 Julian; 379 Theodosius backs Catholics.

- Aftershock: ~100 years of Gothic/Vandal Arian rule; restored by orthodox powers.

- Strategic outcome: sectarian strife weakens the East and eases Islam’s later advance.

Notable figures: Arius, Athanasius, Julian the Apostate, Theodosius; councils (Nicaea).

3. Three Doctors of the Church

Russell spotlights Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine as the triumvirate who set the mould of Western Church-State relations, scripture, monasticism, and theology.

Russell offers a deep appreciation for the role of three figures—St. Ambrose, St. Jerome, and St. Augustine—in shaping the intellectual foundation of the Western Church. These men, known as the Doctors of the Church, each contributed to different dimensions of Christian thought. St. Ambrose articulated the relationship between Church and State, establishing the Church’s authority over secular rulers. St. Jerome provided the Western Church with the Latin Bible, the Vulgate, and played a critical role in the rise of monasticism.

“Four men are called the Doctors of the Western Church: St Ambrose, St Jerome, St Augustine, and Pope Gregory the Great,” but the chapter of A History of Western Philosophy treats the first three as a single generation, situated “between the victory of the Catholic Church … and the barbarian invasion.”

Ambrose, the bishop of imperial Milan, spoke to emperors as “an equal, sometimes as a superior,” crystallizing ecclesiastical independence that would challenge sovereigns for a millennium.

Jerome’s epoch-making Vulgate replaced Septuagint-based Latin versions; he defended a return to the Hebrew text—“Let him who would challenge aught in this translation ask the Jews”—despite initial hostility.

St. Augustine, perhaps the most important of the three. Augustine’s doctrinal architecture would dominate until the Reformation and shape Luther and Calvin. His City of God and other works were a cornerstone for centuries of theological and philosophical debate, impacting even Protestant thinkers like Luther and Calvin.

In short: Ambrose = Church over State; Jerome = text and monastic impulse; Augustine = theological system. Russell’s vignettes (Ambrose’s miracle tales; Jerome’s ascetic “tears and groans… clad in sackcloth” life) humanize their authority while underscoring their strategic roles.

Main points:

- Periodization: Catholic ascendancy (379) to Gothic/Vandal disruption; learned culture wanes for ~1,000 years before equals reappear.

- Ambrose: architect of Church autonomy vis-à-vis the State; forceful Milan bishop.

- Jerome: the Vulgate; philological turn to Hebrew sources; sparks and sustains monasticism.

- Augustine: systematizes doctrine; later animates Protestant debates.

- Color notes: Ambrose’s miracle-finding; Jerome’s desert asceticism and quarrels (Origen/Pelagius).

Notable figures: Ambrose (d. 395), Jerome (b. 345), Augustine; also Alaric, Justinian, Lombards, Franks as contextual actors.

Russell’s verdict is sweeping: “Few men have surpassed these three in influence on the course of history.”

4. St Augustine’s Philosophy and Theology

Russell organizes Augustine around three strands: pure philosophy (especially time), a Christian philosophy of history (the City of God), and soteriology (grace vs. Pelagius).

Philosophically, Augustine’s originality surfaces when he insists on creatio ex nihilo and derives a strikingly “relativistic” theory of time: the world was not created earlier because “there was no ‘sooner’”—time itself begins with creation; God stands in an eternal present (“no before and after”). Russell quotes Augustine’s famous hesitation: “What, then, is time? … if I wish to explain … I know not,” using it to show both insight and limits.

Historically, Augustine fuses Jewish eschatology, Pauline predestination, and the Roman crisis into a master narrative that allowed Christians to absorb the fall of the West without theological panic; the long-run result was a sharpened Church–State dualism and a theocratic ideal in the Latin Middle Ages.

Theologically, his anti-Pelagian stance is fierce: human nature is radically fallen; grace alone saves; and even unbaptized infants are damned—positions that later fed both medieval rigor and Reformation debates.

Main points:

- Time & creation: “Time was created when the world was created”; God is timeless.

- Signature question: “What, then, is time? … I know not.”

- City of God: not “fundamentally original,” but a decisive synthesis; underwrites Church primacy and a Church–State separation that empowered papal claims.

- Anti-Pelagian doctrine: inherited guilt, irresistible grace, predestination; Council of Orange (529) caps the semi-Pelagian fight.

Notable figures: Augustine; Pelagius; St Paul; St Ambrose.

5. The Fifth and Sixth Centuries

Russell’s survey moves from the fifth-century breakup of imperial order to the sixth-century attempts at reconstruction. After 430 (Augustine’s death) philosophy wanes; Germanic polities replace Roman bureaucracy; roads and long-distance trade decay; the Church alone retains a fragile central authority. He marks the hinge events with numbers: Alaric sacks Rome (410); the Western Empire ends (476); Attila is checked at Châlons (451); Chalcedon defines two natures in Christ (451).

Under Theodoric, Italy briefly enjoys orderly Roman administration—until fears of intrigue end with Boethius’s execution (524).

Justinian’s reconquest begins in 535, lasts eighteen years, and leaves Italy wracked: “Rome was five times captured, thrice by Byzantines, twice by Goths,” and administrative corruption turns subjects against Byzantium.

In 568, Lombards invade, and a two-century struggle ensues.

Across this turbulence, Russell isolates four culture-makers: Boethius, Justinian, Benedict, Gregory—bridges from late antiquity to medieval order.

Main points:

- Social reversion to localism; Church as sole supra-local authority.

- Chalcedon (451): one Person, two natures; papal influence decisive.

- Boethius as Platonic conduit amid Gothic politics (d. 524).

- Justinian’s wars (18 years); Rome taken five times; Lombards arrive (568).

Notable figures: Theodoric; Boethius; Justinian; Theodora; Pope Leo; Attila.

6. St. Benedict and Gregory the Great

This chapter pivots from imperial politics to institutional imagination. Benedict’s Rule supplies the durable grammar of Western monasticism—so influential that Russell calls the Dialogues our main source for Benedict’s life and notes the Rule “became the model for all Western monasteries except those of Ireland or founded by Irishmen.”

Gregory the Great, “in a very real sense the last of the Romans,” fuses aristocratic command with ecclesiastical purpose: prefect of Rome (573), monk, papal envoy (579–585), abbot (585–590), then pope. As statesman, he expands papal authority, manages diplomacy amid Lombard pressure, and drives mission: he instructs Augustine of Canterbury not to smash pagan temples in England but to cleanse and re-consecrate them as churches—practical inculturation that works.

Russell’s verdict is crisp: Roman law, monasticism, and the papacy exert their later weight largely through Justinian, Benedict, and Gregory; the sixth century’s leaders were “less civilized” than their forebears, but they forged institutions that ultimately tamed the barbarians.

Main points:

- Benedict’s Rule as Western monastic template; source: Gregory’s Dialogues.

- Gregory’s career arc (573 prefect → papal envoy → abbot → pope) and diplomatic realism.

- Mission strategy in England: “idols … destroyed” but temples consecrated as churches.

- Net effect: strengthened papal power and a monastic network that stabilizes post-Roman Europe.

Notable figures: St Benedict; Gregory the Great; St Augustine of Canterbury.

Part II: The Schoolmen

7. The Papacy in the Dark Ages

Russell frames A.D. 600–1000 as decisive for how papacy and State would negotiate power in medieval Europe.

The papacy’s position oscillates: sometimes subordinate to the Greek emperor, sometimes to the Western emperor, sometimes captured by Roman aristocracy. Yet, opportunistic popes of the 8th–9th centuries consolidate a tradition of papal power, aided less by their own arms than by political alignments—first with Lombards, ultimately with Franks under Charlemagne, birthing the Holy Roman Empire’s ideal of Pope–Emperor harmony. In practice, harmony decays with Carolingian weakness; the 10th century sees aristocratic capture of Rome and a crisis in Church governance.

Russell highlights Nicholas I (858–67) elevating papal jurisdiction (notably in marital and episcopal disputes) but admits the long-run setback of Eastern resistance.

The chapter’s through-line: scholasticism will later rationalize many of these tensions, but the institutional battlefield is set here—jurisdiction, appointment of bishops, divorce cases, and the principle that Eastern patriarchs would not submit to papal control.

Main points:

- A.D. 600–1000 “is of vital importance” for Church–State relations.

- Eastern refusal of papal jurisdiction catalyzes the East–West split.

- Alliance with Franks → Holy Roman Empire; later Carolingian decay.

- Nicholas I pushes papal supremacy, esp. on bishops and royal divorces.

- On the Byzantine quarrel: “The day of king-priests and emperor-pontiffs is past…” (Papal reply).

Notable figures: Gregory the Great; Charlemagne; Nicholas I; Photius; Basil I.

8. John the Scot (Johannes Scotus Eriugena) (A.D. 815-877)

Russell presents John the Scot as the 9th-century’s startling intellectual—so much so that the otherwise “dark” century is “redeemed” by his figure. His masterwork De Divisione Naturae elaborates a four-fold (Russell lists five modes) division of nature spanning what creates/does not create and is/ is not created—an audacious Neoplatonic metaphysic shading toward pantheism.

John argues that authentic authority flows from reason: “true authority does not oppose right reason… authority is derived from reason, not reason from authority,” anticipating scholastic appeals to ratio while risking orthodoxy.

He reworks the problem of evil (nothing is “truly evil” in God’s order) and treats creation as an eternal procession, positions that later alarm Church critics. Russell, sympathetic yet cautious, sees in John an early synthesis of Greek metaphysics with Latin theology that foreshadows scholasticism and later disputes over universals, being, and divine ideas.

The chapter is key for the keyword arc—reason and faith, metaphysics, universals—that will animate medieval philosophy.

Main points:

- John’s prestige marks a high-intellectual anomaly within the 9th century.

- Reason > Authority: authority “is derived from reason.”

- Division of Nature: multi-part schema of creating/created natures.

- Evil reinterpreted; creation as eternal procession.

Notable figures: John the Scot; (contextually) Bede, Alcuin—supports of learning that gird the period.

9. Ecclesiastical Reform in the Eleventh Century

This chapter tracks the Cluniac and papal reforms aimed at prising the Church from secular control—a precondition for later scholasticism to flourish within stable institutions.

Russell states the reformers’ goal plainly: to free the Church from kings’ control, especially in appointments. The reorganization proceeds through orders and canon law, with Cluny as “one of the chief organs.” Gregory VII (Hildebrand, 1073–85) raises the stakes: enforcing clerical celibacy, battling lay investiture, and seeking a dual unification—spiritual realm under the Pope, temporal realm under the Emperor—that “would have created a real theocracy.” Yet the settlement is mixed.

Even when popes seem to “win,” Russell is cool-eyed: “The Pope’s victory, however, was illusory; after the concordats, the kings became weaker and the emperors stronger as absolute monarchs.”

By 1122 (Concordat of Worms), formulae balance ritual and right; the “scholasticism” of church–state theory becomes a key intellectual battlefield, with papacy, bishops, and empire recalibrating power.

Main points:

- Reform = independence from secular investiture and control.

- Cluny central as organizational engine.

- Gregory VII (1073–85) pushes discipline + papal monarchy.

- Post-reform paradox: papal “victory” illusory; monarchies harden.

Notable figures: Gregory VII; Henry IV (background); the Cluniacs.

10. Mohammedan Culture and Philosophy

A History of Western Philosophy treats Arabic philosophy less as an originator than as a transmitter—indispensable in preserving and relaying Aristotle, Galen, mathematics, and astronomy to Latin Europe when “the dark ages intervened.”

The influence of Mohammedan culture and philosophy during the medieval period is often overlooked, but its impact on Western thought was profound. The Arab conquests, fueled by the unification of faith and philosophy, contributed to significant advancements in mathematics, medicine, and philosophy, all of which were transmitted to the West through scholars like Avicenna and Averroes.

Russell profiles Avicenna (980–1037), both physician and philosopher, whose nuanced account of universals—“Genera… are at once before things, in things, and after things” (in God’s mind, in nature, in our thought)—anticipates scholastic treatments.

Averroes (1126–98) becomes more influential in Christian than in Mohammedan philosophy, spurring Averroists who deny immortality and shaping university debates in Paris (notably among Franciscans).

Russell’s verdict is blunt: Arabic philosophers are “essentially commentators,” but their civilizational role as transmitters—with Jewish intermediaries like Maimonides (b. 1135)—is epoch-making for scholasticism and the rise of reason and faith discourse in the 13th century.

Main points:

- Avicenna on universals: before/in/after things.

- Averroes → strong Latin reception; early Averroists.

- Arabic thought as transmitter of Greek science and philosophy.

- Maimonides reconciles Aristotle and Jewish theology; rejects astrology; affirms creatio ex nihilo, “creation out of nothing”.

11. The Twelfth Century