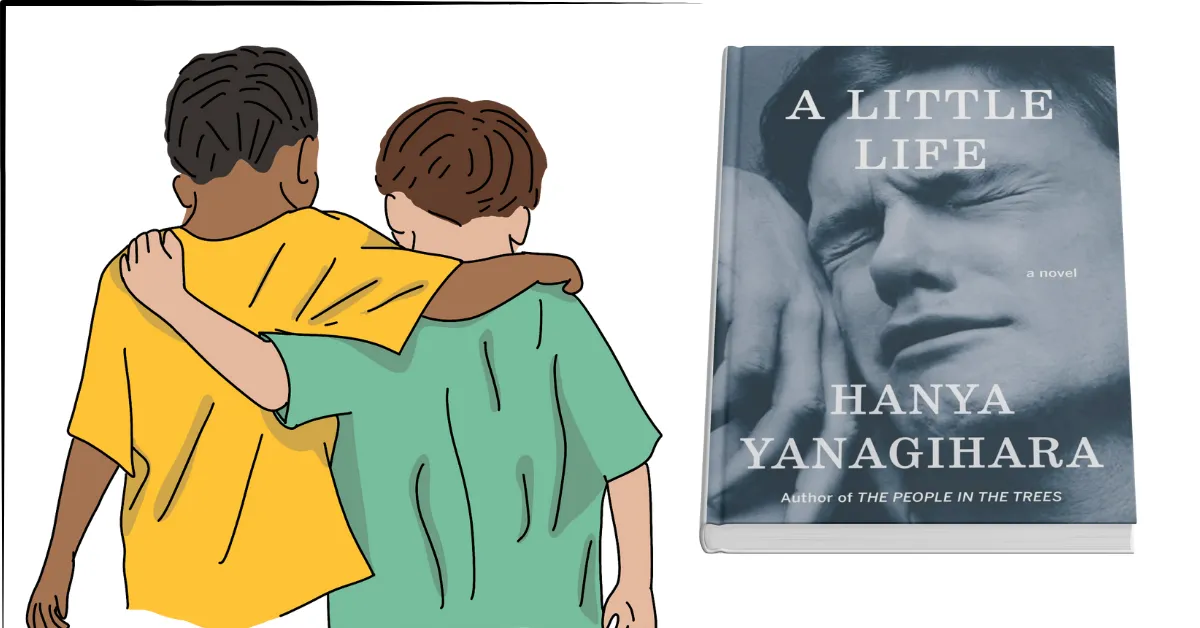

Published in 2015 by Doubleday in the United States and Picador in the United Kingdom, A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara quickly became one of the most discussed works of contemporary literary fiction. At over 700 pages, this monumental novel is both a deeply intimate character study and a searing depiction of trauma, friendship, and the fragile boundaries of human endurance.

In the years since its release, it has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the National Book Award, and the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, cementing its status as a modern classic.

The book’s reception has been polarising—praised for its emotional intensity and criticised for its relentless portrayal of suffering. But whether lauded or contested, A Little Life has entered the cultural conversation as one of the most haunting works of the 21st century.

A Little Life belongs to the genre of literary fiction but incorporates elements of psychological realism and tragic epic. It spans several decades, tracing the intertwined lives of four college friends—Willem, JB, Malcolm, and Jude—against the vibrant backdrop of New York City’s cultural, artistic, and professional landscapes.

Hanya Yanagihara, a Hawaiian-born American novelist and editor, is known for her fearless narrative ambition.

Before A Little Life, she published The People in the Trees (2013), which already displayed her interest in morally complex characters and intricate timelines. With A Little Life, she created a work that transcends conventional storytelling by shifting between perspectives, collapsing time frames, and immersing readers in the emotional and psychological worlds of her characters.

Reading A Little Life is less like following a plot and more like living inside the minds and hearts of its characters. It is a novel about the devastating weight of past trauma, the life-saving power of chosen family, and the limits of love’s ability to heal. Its significance lies in its emotional authenticity—an unflinching reminder that life is at once unbearably cruel and achingly beautiful.

As one character reflects:

“Wasn’t friendship its own miracle, the finding of another person who made the entire lonely world seem somehow less lonely?” (Yanagihara, A Little Life)

The book’s strengths—its depth of characterisation, lyrical prose, and thematic richness—are also what make it emotionally demanding. And yet, for many readers, that emotional demand is precisely what makes A Little Life unforgettable.

Table of Contents

1. Summary of the Book

Part 1: Beginnings and Bonds

A Little Life begins with four young men—Willem Ragnarsson, Jude St. Francis, JB Marion, and Malcolm Irvine—sharing a modest apartment in New York City after graduating from a prestigious Massachusetts college.

Each carries dreams as distinct as their personalities: Willem, the kind and grounded aspiring actor; JB, the flamboyant and ambitious painter; Malcolm, the architect navigating identity and family pressures; and Jude, the brilliant but secretive lawyer whose mysterious past and physical limitations intrigue yet distance him from the others.

From the outset, Yanagihara sets the tone: the narrative is less about external events and more about the slow, immersive excavation of character. The early chapters establish their camaraderie and the small rituals that define young adulthood in the city—cheap dinners, shared bills, and debates over art, politics, and ambition.

Yet it is Jude who quietly becomes the gravitational center of the story. His limp, chronic pain, and occasional disappearances hint at a traumatic past he refuses to discuss.

As the others move forward in their careers—Willem landing stage roles, JB breaking into the New York art scene, Malcolm joining a prestigious architecture firm—Jude’s guardedness deepens. Despite his professional brilliance, he carries an unshakeable sense of unworthiness.

Hints of the Unseen Past

The novel gradually reveals that Jude’s life before college was marked by severe abuse, neglect, and exploitation—though Yanagihara withholds explicit details at first. This withholding creates an atmosphere of persistent tension: the reader senses the enormity of Jude’s suffering long before it is named. His physical scars and worsening health are constant reminders that the past is never truly past.

Willem, perhaps more than anyone, sees through Jude’s attempts at concealment. Their friendship grows into a quiet partnership, grounded in Willem’s steady loyalty and Jude’s cautious trust. JB and Malcolm, though important, begin to drift in and out of the narrative, as the emotional core increasingly focuses on the bond between Jude and Willem.

A City as a Character

New York City is not just a backdrop—it’s a living, breathing presence that shapes the friends’ journeys.

From cramped lofts in SoHo to sleek apartments overlooking the Hudson, the changing geography of their lives mirrors their shifting fortunes. The city’s art galleries, courtrooms, theaters, and brownstones become stages on which ambition, intimacy, and heartbreak play out.

“In New York, he felt the city was a collection of private worlds, all orbiting each other, colliding in ways both deliberate and accidental.” (A Little Life)

Part 2: Success, Secrets, and the Deepening Shadows

As years pass, the four friends achieve varying levels of professional success. Willem’s acting career blossoms, JB’s art gains recognition, Malcolm designs significant projects, and Jude rises to become a respected litigator at a top New York law firm.

Outwardly, they embody the dream of youthful ambition fulfilled. Yet, beneath this success, Jude’s internal battles grow more acute.

The Unraveling of JB’s Friendship

JB, whose art increasingly draws from his circle of friends for inspiration, crosses a line when he paints Jude in a moment that feels cruelly exploitative. This betrayal creates a permanent rift between Jude and JB, foreshadowing the fragility of even the strongest friendships when trust is breached. JB’s struggles with substance abuse compound the distance.

Jude’s Past Emerges

Through flashbacks and fragmented recollections, Yanagihara begins to reveal the contours of Jude’s traumatic childhood—a life marked by abandonment, abuse by those entrusted with his care, and years of exploitation at the hands of Brother Luke, a monk who initially rescued him from an abusive orphanage but later subjected him to prolonged sexual abuse and forced prostitution.

The narrative’s restrained, matter-of-fact tone in these sections makes them even more devastating.

His chronic pain and self-harming habits are not only physical legacies but also manifestations of deep psychological wounds. Jude’s refusal to seek help—medical or emotional—becomes a central tension in the story. Even when surrounded by love and friendship, he cannot fully believe he deserves them.

“He had no right to ask for anything, no right to expect anything—he was lucky to have anything at all.” (A Little Life)

The Deepening Bond with Willem

Willem remains Jude’s anchor, offering unwavering loyalty without demanding full disclosure of his past. Over time, their relationship deepens beyond friendship into a romantic and physical partnership.

This shift is tender and understated, marked by Willem’s patience and Jude’s slow, cautious acceptance of intimacy. Yet even in love, Jude’s trauma shapes every interaction; he is unable to escape the belief that he is irreparably damaged.

The Role of Harold and Julia

Jude’s law professor, Harold, and his wife Julia become parental figures, eventually adopting him as an adult. This act of unconditional love offers Jude a form of family he never had, though his capacity to accept it remains limited. Harold, narrating some chapters, offers insight into Jude’s quiet generosity and brilliance, but also his profound self-loathing.

Part 3: Loss, Love, and the Final Descent

The Height of Connection

In the middle years of the narrative, A Little Life offers brief periods of warmth and stability for Jude. His romantic partnership with Willem becomes a central source of emotional sustenance. They buy a house together in the country, creating a quiet refuge away from the intensity of New York City.

For the first time, Jude experiences a semblance of domestic peace—cooking meals with Willem, walking in the gardens, and sharing mornings without urgency.

But even here, the shadow of his past persists. Jude’s physical condition worsens, with his mobility increasingly impaired and his pain escalating. His inability to fully open up to Willem about the depth of his trauma strains their intimacy, though Willem refuses to abandon him.

“There were times when he looked at Willem and thought: this is what love is, and it will kill me.” (A Little Life)

Tragedy Strikes

The most devastating turning point comes when Willem dies suddenly in a car accident, along with their friend and Harold’s son, Malcolm. This catastrophic loss shatters Jude’s fragile stability. The grief is overwhelming, and without Willem’s constant presence, Jude’s world begins to collapse. His sense of worthlessness deepens into a conviction that life without Willem is unbearable.

JB, now sober and regretful, attempts reconciliation, but Jude cannot fully return to the old friendship. Harold continues to love and support him, but Jude retreats further into isolation.

The Final Decline

As the novel moves toward its close, Jude’s health deteriorates dramatically. His chronic pain becomes nearly unmanageable, and his mental state grows more fragile. Despite Harold’s constant reassurances and attempts to give him reasons to live, Jude’s self-destructive impulses intensify.

In one of the book’s most heart-wrenching turns, Jude takes his own life, leaving behind letters to Harold and a legacy of both brilliance and unimaginable suffering. Harold’s closing narration reflects on Jude’s life with a mix of love, grief, and anger at the cruelty he endured.

“He was my son, and he was my life. And I miss him so much I can’t bear it.” (A Little Life)

2. Setting

The novel’s primary setting—New York City—is as much a character as any of the people in it. The city’s artistic, legal, and social milieus form the backdrop for the characters’ ambitions and struggles.

From cramped apartments in lower Manhattan to countryside escapes, each location mirrors the characters’ internal landscapes: bustling, chaotic, aspirational, and sometimes suffocating.

3. Analysis

3.1 Characters

Jude St. Francis – The Emotional Core

Jude is the axis around which A Little Life turns. Brilliant, disciplined, and fiercely private, he embodies both resilience and fragility. His professional success as a lawyer contrasts starkly with his private world of chronic pain, self-harm, and emotional withdrawal. The layers of Jude’s character are revealed gradually—each memory, scar, and relationship peeling back the protective shell he maintains.

Motivations:

- Survival: Jude’s early life taught him to endure, not to thrive. His achievements are less about ambition and more about proving his right to exist.

- Control: His perfectionism in work and relationships is a coping mechanism against a life once governed by chaos and abuse.

- Self-negation: Despite external success, he believes he is undeserving of love or happiness.

Key Relationship: His connection with Willem is the most transformative—offering moments of genuine joy, though never fully erasing the damage of the past.

“You were the only thing that made life worth enduring.” (A Little Life)

Willem Ragnarsson – The Anchor

Willem is Jude’s closest friend and later, romantic partner. Kind, patient, and unassuming, Willem provides the emotional stability that Jude cannot give himself. His life as an actor mirrors Jude’s in its external glamour and internal modesty.

Complexity: Willem’s loyalty is unwavering, but it comes at personal cost. His refusal to push Jude into revealing his trauma stems from respect, yet it also allows Jude to remain trapped within it.

JB Marion – The Flawed Friend

JB is flamboyant, ambitious, and often self-absorbed. His art, which draws heavily from his friendships, becomes a point of betrayal when he uses Jude’s image without consent in a way that feels mocking. JB’s journey through substance abuse, estrangement, and eventual sobriety shows a man capable of reflection and regret, but whose reconciliation with Jude remains incomplete.

Malcolm Irvine – The Quiet Observer

Malcolm, the architect, is less emotionally central than Jude or Willem but plays a key role in grounding the group in its early years. His death alongside Willem marks one of the novel’s most devastating losses, underscoring the fragility of life and relationships.

Harold Stein – The Chosen Father

Harold, Jude’s law professor turned adoptive father, offers the unconditional parental love Jude never had. His patience and acceptance contrast sharply with the cruelty of Jude’s biological family and childhood caretakers. Harold’s grief-stricken narration in the closing chapters provides the novel’s final, wrenching emotional note.

Supporting Figures

- Brother Luke – A symbol of betrayal and predation, his exploitation of Jude marks the beginning of his lifelong mistrust of intimacy.

- Caleb – A later abusive relationship that mirrors Jude’s earlier victimization, reinforcing the cyclical nature of trauma.

- Julia – Harold’s wife, who extends warmth and maternal care to Jude, though always through Harold’s mediation.

Alright — here’s Section 3.2: Writing Style and Structure for A Little Life.

3.2 Writing Style and Structure

Hanya Yanagihara’s writing in A Little Life is deliberate, immersive, and unflinching. The prose refuses to shy away from emotional or physical pain, yet it also allows space for quiet, tender moments. The style itself is part of the book’s impact—its density and precision force the reader into intimate proximity with the characters’ inner lives.

Narrative Perspective

The novel primarily uses a third-person omniscient narrator with occasional first-person interjections from Harold. This choice allows Yanagihara to oscillate between a panoramic view of the friends’ shared world and an intensely close lens on Jude’s private suffering.

- Harold’s first-person sections humanize the narrative further, offering a voice of compassion that counters the relentless harshness of Jude’s inner monologue.

- The shifting perspectives give the reader both emotional distance and emotional immersion—a tension that mirrors Jude’s own reluctance to let others fully in.

Structure

The book’s structure is non-linear but purposeful.

- Flashbacks emerge without warning, blending into present-day scenes, creating a layered psychological portrait.

- Yanagihara reveals Jude’s past gradually, withholding key events until late in the narrative, which builds both suspense and dread.

- The narrative spans decades, yet maintains a sense of intimacy by focusing on domestic, professional, and interpersonal details.

Language and Tone

Yanagihara’s language is meticulous and often lyrical, particularly when describing relationships, physical spaces, or moments of quiet connection:

“There were stretches of time, days sometimes, when he felt almost normal, when the ache and the damage felt distant.” (A Little Life)

Tone shifts from clinical restraint—especially in depicting abuse—to emotional saturation in moments of love, grief, or beauty. This tonal duality intensifies the reader’s experience, making the moments of relief feel like hard-earned respites.

Use of Literary Devices

- Repetition: Certain phrases and motifs recur (“You’re safe now,” “I’m sorry”), underscoring Jude’s ongoing internal battles.

- Symbolism: Physical spaces—apartments, the country house—often represent emotional states, while Jude’s damaged legs become a living metaphor for the scars of trauma.

- Foreshadowing: Hints of tragedy, particularly regarding Willem’s fate, appear subtly throughout, lending the book a quiet inevitability.

Pacing

The pacing is intentionally uneven:

- Slow-burning stretches dwell on domestic routines, work projects, or shared meals, mirroring the endurance of everyday life.

- Sudden accelerations occur in crisis moments—accidents, revelations, or deaths—mirroring how trauma disrupts life’s continuity.

This rhythm deepens the realism of the novel’s emotional landscape, while also challenging the reader’s stamina and willingness to sit with discomfort.

3.3 Themes and Symbolism

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is thematically dense, weaving together ideas of friendship, love, trauma, identity, and endurance. The novel’s power lies in its refusal to reduce these themes to simple resolutions—each exists in tension with the others, creating a narrative that is both devastating and deeply human.

Friendship as Chosen Family

One of the novel’s most enduring messages is that friendship can be as binding and profound as blood ties. For Jude, whose biological family and early caretakers were abusive or absent, his friends—Willem, JB, Malcolm—become the foundation of his emotional survival.

- Willem’s steadfast loyalty and Harold’s paternal love challenge Jude’s belief that he is unworthy of care.

- The group’s shared history, from college days to middle age, mirrors the ebb and flow of family life—complete with conflicts, reconciliations, and irrevocable losses.

Trauma and Its Echoes

Perhaps the most central theme, trauma in A Little Life is portrayed as lifelong and deeply physical.

- Jude’s abuse leaves him with chronic pain, limited mobility, and self-destructive behaviors such as cutting.

- Yanagihara resists the narrative of total “healing,” instead depicting trauma as a permanent part of identity—something one can live with, but not erase.

“He had been so determined, all his life, to keep moving, to keep running away from the past, and yet the past was still there, waiting for him.”

Love in Its Many Forms

Romantic love, platonic love, and parental love all feature prominently. The love between Jude and Willem is one of mutual care, though marked by Jude’s inability to fully accept it. Harold’s adoption of Jude as an adult underscores that it is never too late to find family, though the scars of earlier neglect remain.

Self-Worth and Identity

Jude’s professional success as a lawyer stands in stark contrast to his private self-loathing. The tension between external achievement and internal emptiness is a recurring motif, inviting readers to question societal assumptions about success as a measure of personal worth.

Symbolism

- Jude’s Legs: His damaged legs, the result of severe childhood abuse, become a physical manifestation of his trauma—visible to others yet carrying a history only he fully knows.

- The Country House: Purchased by Jude and Willem, it symbolizes fleeting peace and the possibility of safety, yet ultimately becomes another site of grief after Willem’s death.

- Cutting Implements: Represent both control and destruction—Jude’s attempt to manage emotional pain through physical expression.

Hope vs. Despair

The novel never offers a fully hopeful ending, but moments of connection, art, and beauty emerge throughout. These moments do not erase suffering, but they coexist with it, acknowledging the complexity of real life.

4. Evaluation

Strengths

- Deep Characterization – The emotional depth of Jude, Willem, Harold, and the supporting cast is extraordinary. Yanagihara commits to developing them over decades, allowing readers to witness their transformations, regressions, and moral complexities.

- Emotional Authenticity – The book’s power lies in its unflinching honesty about trauma, love, and the limits of healing. It doesn’t sugarcoat the long shadow of abuse, which makes its moments of tenderness all the more impactful.

- Prose Style – Lyrical yet precise, Yanagihara’s sentences linger in the mind, often balancing beauty and brutality in the same paragraph.

- Exploration of Chosen Family – The portrayal of friendship as an enduring life force feels both radical and universal.

- Narrative Ambition – Spanning more than thirty years, the novel’s scale is impressive without losing sight of intimate details.

Weaknesses

- Graphic Content – The relentless depictions of abuse and self-harm have been criticized for being excessive and, for some, emotionally overwhelming.

- Length and Pacing – At over 700 pages, the novel can feel slow in certain stretches, particularly for readers expecting more plot-driven pacing.

- Emotional Toll – While intentional, the book’s heaviness means it demands significant emotional resilience from its audience.

- Limited Perspective Diversity – Although the characters are richly drawn, the central narrative remains heavily Jude-focused, which some critics argue narrows the thematic scope.

Impact

Reading A Little Life is often described as a transformative experience. It leaves an emotional residue that lingers long after finishing—eliciting tears, reflection, and sometimes a need for recovery time.

- The novel has sparked discussions about how literature should portray trauma, with debates in literary circles about whether the book is empathetic or exploitative.

- According to Goodreads data (as of 2024), it maintains an average rating above 4/5 with over 400,000 ratings, a testament to its passionate readership despite its polarizing nature.

Comparison with Similar Works

- Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch – Shares a focus on trauma, found family, and the long arc of life, though A Little Life is more emotionally relentless.

- Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels – Similar in scope and intimacy, but Ferrante’s work emphasizes socio-political context alongside personal drama, whereas Yanagihara keeps the focus tightly on interpersonal relationships.

- Toni Morrison’s Beloved – Both novels confront the lasting legacy of trauma, though Beloved weaves more historical and communal dimensions.

Reception and Criticism

Upon release in 2015:

- Praise – Many critics lauded its ambition, emotional power, and rich character development. The New Yorker called it “relentlessly compelling” and “a modern epic of friendship.”

- Criticism – Some reviewers accused it of “trauma porn,” questioning whether the extremity of Jude’s suffering was necessary.

- Shortlisted for the 2015 Booker Prize and a finalist for the National Book Award, the book also won the Kirkus Prize for Fiction.

Adaptations

- In 2022, A Little Life was adapted into a stage play in London’s West End, directed by Ivo van Hove and starring James Norton as Jude. The production received strong reviews for its acting, but also warnings about its harrowing content.

Notable Information

- The novel is frequently included on lists like “Books That Will Break Your Heart” or “Most Devastating Modern Novels.”

- It has inspired numerous online support groups and reading communities where people process the emotional weight together.

5. Personal Insight with Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading A Little Life feels less like consuming a fictional narrative and more like confronting a profound human case study in resilience, identity, and the long-term consequences of trauma. It is, at its core, a psychological and sociological text disguised as a novel—its emotional punch amplified by Hanya Yanagihara’s refusal to grant easy answers.

In recent years, global awareness of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) has grown significantly. According to a 2023 CDC study, 1 in 6 adults report experiencing four or more ACEs, which is strongly linked to lifelong mental health struggles, chronic disease, and early mortality.

Jude’s journey reflects these realities:

- Chronic pain as a result of early abuse mirrors findings in trauma medicine linking severe childhood abuse to somatic disorders.

- Difficulty trusting relationships aligns with attachment theory research showing that early neglect disrupts the brain’s capacity for secure bonds.

By embedding these truths in fiction, A Little Life makes statistical abstractions painfully real, giving readers a deeply personal entry point into otherwise clinical data.

Chosen Family in the LGBTQ+ Context

The novel’s portrayal of chosen family resonates particularly within LGBTQ+ communities, where biological family rejection is disproportionately high.

A 2022 Trevor Project survey found that 45% of LGBTQ+ youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, with family acceptance as one of the most significant protective factors.

Willem, Harold, and the others function as Jude’s protective factors—his lifeline, even when he struggles to believe he deserves them.

Self-Harm and Mental Health Stigma

Yanagihara addresses self-harm without romanticizing it, portraying it as compulsive, shame-laden, and rooted in deep psychological pain.

- In 2021, the WHO reported that nearly 700,000 people die from suicide annually, with millions more engaging in self-harming behaviors.

- The book’s raw depiction serves as a conversation starter for destigmatizing mental health struggles and encouraging early intervention.

Educational and Psychological Applications

This novel is valuable in:

- Clinical psychology training, as a fictional but authentic-seeming case study of complex PTSD.

- Literature courses, for discussions on the ethics of depicting suffering.

- Social work education, to explore concepts of resilience, support networks, and the long tail of trauma.

Why It Matters Now

In an age of digital overstimulation and bite-sized storytelling, A Little Life demands sustained attention, patience, and emotional openness.

It reminds us that literature can still serve as a moral reckoning—not merely entertainment. It asks readers to carry Jude’s story beyond the page, into advocacy, awareness, and personal reflection.

6. Conclusion

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life is not a novel one simply “reads”—it is an emotional immersion that challenges, devastates, and ultimately expands the reader’s capacity for empathy.

Across more than 700 pages, it refuses to flinch from the darkest realities of abuse, chronic pain, and mental illness, yet it equally refuses to understate the sustaining power of love, loyalty, and chosen family.

The book’s literary ambition lies in its duality: on one hand, it is an unrelenting portrayal of suffering; on the other, it is a sweeping testament to the endurance of human connection. Its complexity is not merely in the narrative structure but in its moral positioning—it neither condemns nor redeems fully, leaving space for readers to wrestle with their own interpretations.

I would recommend A Little Life to:

- Readers who value deep, character-driven narratives.

- Those prepared for emotional intensity and unfiltered depictions of trauma.

- Academics and book clubs willing to engage with questions about the ethics of storytelling and the representation of marginalized experiences.

In a literary landscape often driven by market trends and formulaic arcs, A Little Life stands out as a monumental work of psychological fiction, one that will be remembered not for how easy it was to read, but for how impossible it was to forget. It is a book that insists on staying with you—long after the last page is turned.