E.M. Forster’s 1924 novel, A Passage to India, stands as a landmark of 20th-century English literature, a work that delves into the intricate and often painful dynamics between colonial rulers and the colonized.

This article undertakes a comprehensive analysis of the novel, exploring its historical context, complex characters, and profound philosophical questions.

As a work of modernist and post-colonial literature, it was written during a period of burgeoning Indian independence movements, a time when the British Raj was facing increasing challenges to its authority.1

Forster’s personal experiences and friendships with Indian men, to whom the book is dedicated, deeply influenced its central inquiry into whether genuine human intimacy can survive in an environment of systemic racial and cultural prejudice.

A Passage to India‘s ultimate tragedy lies not in the failure of individual kindness but in the overwhelming, almost metaphysical, power of institutionalized prejudice and the deep cultural divisions that permeate society.

The narrative demonstrates that while personal connection is possible, it is ultimately unsustainable when society itself is fundamentally structured to divide, a truth that the main characters, Adela Quested and Dr. Aziz, learn at great personal cost.

Table of Contents

1. Overview

A Passage to India delivers a potent critique of colonial ideology by dismantling the illusion of a monolithic, easily governed world. The novel solves the problem of how to explore the fragile hope for human connection in the face of insurmountable cultural and political divides.

At its heart, the book’s profound idea is that genuine friendship between a colonizer and the colonized is impossible, not due to a lack of individual will, but because the very foundation of their society, the colonial state, actively works to make it so.2

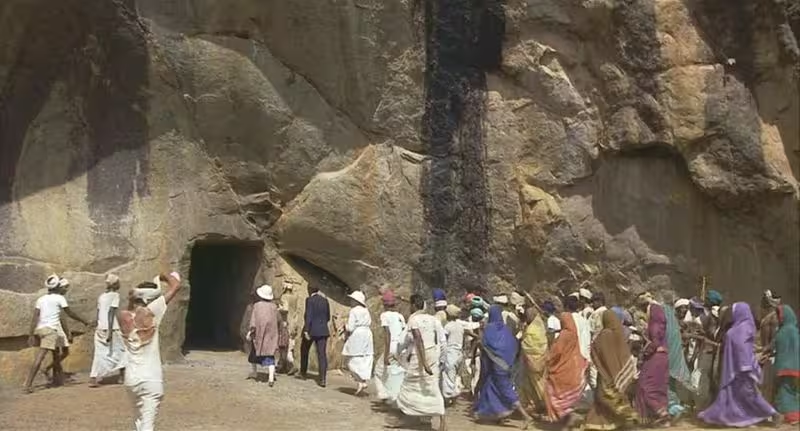

This is powerfully demonstrated when a simple, well-intentioned picnic to the Marabar Caves spirals into a full-blown international incident, revealing how personal relationships are irrevocably compromised by the power structures and racial prejudices of the British Raj.

The legal and social systems of the British administration are shown to be inherently biased, transforming a simple misunderstanding into a widespread “prejudice” and a formal “trial”.3

Critiques from post-colonial theorists like Edward Said affirm this perspective, noting that A Passage to India exposes the West’s “paternalistic control” over an exoticized and inferior “Other” India.4 A Passage to India is highly recommended for readers who appreciate deep psychological analysis and a nuanced critique of power dynamics.

The book is less suited for those seeking a straightforward, action-driven plot or a simplistic solution to complex social and political issues, as Forster’s narrative deliberately resists easy answers.

2. Background

The British Raj and the Stirrings of Nationalism

A Passage to India is set during a tumultuous and pivotal era in British India. The 1920s witnessed a significant rise in Indian nationalism, with influential figures like Mahatma Gandhi leading movements for self-rule and economic independence.5

The British, in turn, often responded with a combination of repressive measures and limited reforms. The introduction of acts like the “Rowlatt Acts,” which extended wartime restrictions on civil liberties, created an atmosphere of profound unrest and resentment among the native population. The novel’s plot is not merely situated against this historical backdrop but is a direct consequence of it. The characters’ actions and reactions, from Ronny Heaslop’s rigid adherence to colonial protocol to Dr. Aziz’s growing disillusionment and eventual embrace of nationalism, are all causally linked to the political and social climate of the time.

This period was marked by a deep and growing schism between the British and Indian populations, which A Passage to India explores with incisive detail.6

Colonial Power Structures: The Divide-and-Rule Strategy

The foundation of British rule, or “Raj,” was built on an intricate system of racial classification and social hierarchy, a strategy of “divide-and-rule” that ensured British control over the diverse Indian populace.7 Forster masterfully illustrates this through his depiction of the fictional city of Chandrapore, which is sharply divided into two distinct worlds. The Indian city, described as “mean” and “monotonous,” with inhabitants who seem “made of mud,” contrasts starkly with the British civil station, a “totally different place” that is “sensibly planned” with houses “disposed along roads that intersect at right angles”.

This physical separation symbolizes the deep social and psychological divisions that the colonial system enforced, and which Forster suggests are far more potent than any individual’s desire for connection.

The Role of the English Club

The English club in Chandrapore serves as a powerful symbol of this colonial power structure. It is a social enclave and an imperial institution, a “microcosm of Britain” where the British elite socialized, played games, and reinforced their national identity.

The club’s race-selective policies, which exclude Indians even as guests, function as a tangible manifestation of a hegemonic ideology built on “white solidarity”. The club is a place where British officials, feeling “in exile,” find strength in their shared identity and are “fused into a prayer unknown in England”.

Cyril Fielding’s eventual ostracization from this community, following his decision to support Dr. Aziz during the trial, is not merely a social slight but a profound and symbolic rejection of the entire imperial ideology that the club represents. The club’s members view his actions as a betrayal of their collective values, proving that a person who deviates from the “line” weakens the entire system.

3. Summary of A Passage to India

Plot Overview

The narrative of A Passage to India unfolds in three distinct sections—”Mosque,” “Caves,” and “Temple”—each representing a different phase of the characters’ spiritual and psychological journeys.

In the first part, “Mosque,” the reader is introduced to Dr. Aziz, a sensitive and romantic young Muslim physician who, along with his friends, often debates the possibility of genuine friendship with Englishmen.

This section also introduces the elderly Mrs. Moore and her son’s fiancée, Adela Quested, two Englishwomen who have recently arrived in Chandrapore and harbor a naive desire to see the “real India” beyond the confines of the civil station. A chance meeting between Aziz and Mrs. Moore at a mosque sparks an unlikely, and for Aziz, deeply significant, friendship.

Their mutual respect and openness stand in stark contrast to the failed “Bridge Party,” an awkward social gathering hosted by the British to “bridge the gulf” between the two communities. This failure leads to a more private plan: a picnic to the Marabar Caves, arranged by Aziz himself.

The second part, “Caves,” is the narrative’s dramatic and unsettling core. The picnic, initially a chaotic but well-intentioned affair, takes a fateful turn when Mrs. Moore, feeling unwell after visiting the first cave, decides to rest alone.

Adela and Aziz, accompanied by a guide, continue to a higher set of caves. It is here, in the claustrophobic darkness of one of the chambers, that Adela is overwhelmed by a psychological crisis. The experience, which some critics have interpreted as a panic attack triggered by her repressed anxieties about her engagement and her lack of love for Ronny, culminates in an “hallucination” of a sexual assault.

She flees the caves in terror, lacerating herself on thorn bushes. Back in Chandrapore, her panicked and bloodied state is misconstrued by the English community, which quickly falls into a “mob mentality” and a “racial” mindset.8 Aziz is arrested and charged with attempted rape. The subsequent trial becomes a symbolic battleground for the entire colonial system, with Cyril Fielding, the head of the local college, standing as a lone voice of reason in defense of Aziz, a decision that leads to his immediate ostracization from the British community.

In the final part, “Temple,” the fallout from the trial is explored. Adela, driven by her intellectual honesty and a newfound clarity, withdraws her accusation in court, leading to Aziz’s acquittal.

However, the damage is already permanent. The elderly Mrs. Moore, her spirit broken by a profound spiritual crisis in the caves, dies on her voyage back to England. Her influence, however, does not end with her death, as she becomes a local legend known as “Esmiss Esmoor” in the Indian imagination.

Two years later, Aziz, now a doctor in a Hindu state, has embraced his nationalism and is convinced that Fielding has betrayed him by marrying Adela.

In a final, poignant scene, the two friends are reunited by chance. The misunderstanding about Fielding’s marriage is cleared up—he has married Mrs. Moore’s daughter, Stella—but their friendship cannot be fully renewed. Their final ride together concludes with a bittersweet acknowledgment that while they may wish to be friends, the deep-seated divisions of colonial rule, like the very earth and sky, will not permit it..

Setting

The novel’s setting is a crucial element of its symbolic and thematic depth. The city of Chandrapore is presented as a city of two halves: the “mean” and “monotonous” Indian town and the “sensibly planned” but sterile British civil station.

This duality mirrors the social and racial divide of the British Raj. The Marabar Caves, in stark contrast, are ancient and mysterious, predating all human civilization and its divisions.

They are described as a “void in the earth” that reveals the meaninglessness of human constructs, whether colonial or personal.9 The final section of A Passage to India, set in the Hindu state of Mau, offers a different kind of “muddle”—a religious chaos that is nevertheless unifying and free from the rigid divisions of British influence.

4. Analysis of Characters and Themes

1. Characters

Dr. Aziz

Dr. Aziz is introduced as a romantic, sensitive, and hospitable young man who, despite his frustrations with the British, initially yearns for genuine connection with them.

He is an emotional individual, a poet who finds solace in Persian verses and who, despite his Western medical training, is not entirely rational. His character’s development is one of the novel’s central tragedies. The trial, with its public humiliation and violation of his personal life, irrevocably transforms him from an anglophile into a fervent nationalist.

His perceptions of the English, and particularly his generalization that Englishwomen are “haughty and venal,” are not unfounded but are born of his own painful experiences and disappointments within the colonial system. This emotional nature, as opposed to a purely rational one, drives his relationships and, ultimately, his final disillusionment with Fielding.

Adela Quested

Adela’s defining characteristic is her intellectual honesty, a trait that is paradoxically intertwined with a certain psychological and emotional “short-sightedness”.10 She arrives in India with the naive, almost academic, goal of “seeing the real India” and forming a rational opinion about it. Her journey, however, is derailed by the Marabar Caves, which force her to confront a part of herself that is irrational and repressed. The “hallucination” she experiences is the climax of this inner conflict, forcing her to realize her lack of love for her fiancé, Ronny, and to confront her own sexual anxieties in a raw, unmediated way.

Her ultimate act of recanting her testimony in court is a courageous act of justice, but it is one born of a cold, intellectual realization of the truth rather than a passionate affection for Aziz. This cold, honest act is why the Indian community, and even Aziz himself, cannot fully appreciate or accept it.

Mrs. Moore

Mrs. Moore initially acts as A Passage to India’s moral and spiritual center. Her gentle, compassionate nature and her belief in universal love are what initially draw her to Dr. Aziz at the mosque, a friendship of great significance for him. However, this faith is tested and then annihilated by the “echo” of the Marabar Caves.

The “boum” echo, which reduces all sounds and spiritual utterances to the same meaningless noise, causes a profound spiritual apathy in her. She becomes cynical and detached from human relationships, unable to offer her vital testimony at the trial and ultimately abandoning her responsibilities to her son and Adela. Her death at sea, a physical departure from India, is not an end but a transformation, as she becomes a legendary figure, “Esmiss Esmoor,” in the Indian imagination.

This tragic descent serves as a critique of the limitations of a simplistic, inherited faith in the face of an indifferent and chaotic universe.

Cyril Fielding

Cyril Fielding is the archetypal humanist, a man who believes in the power of reason, education, and individual relationships to transcend the cultural divide. As a renegade who defies the social norms of the British club to support Aziz, he embodies the liberal, progressive ideal of a colonizer.

His actions, which include sacrificing his social standing and career to stand with the colonized, are a testament to his belief in personal justice over group loyalty.11 However, his rationalism has its limits. He is blind to the spiritual and emotional depths of India, as symbolized by his preference for the ordered “form and proportion” of Venice over India’s “muddle”.

The final section of A Passage to India, where his friendship with Aziz ultimately fails, demonstrates that even a well-meaning humanist cannot overcome the overwhelming forces of history and colonialism.12

2. Writing Style and Structure

Three-Part Structure

The novel’s tripartite structure—”Mosque,” “Caves,” and “Temple”—is not merely a chronological progression but a deeply thematic and symbolic one. It begins in the “Mosque,” a space of human connection and faith where Aziz’s and Mrs. Moore’s friendship blossoms.

It then moves to the “Caves,” a place of utter nihilism, chaos, and psychological collapse that shatters the possibility of connection. It concludes in the “Temple,” a space of all-encompassing, confusing, and non-Western spirituality that, while seemingly uniting everyone, also confirms the impossibility of true East-West friendship.

This structure reflects the different phases of the characters’ spiritual and psychological journeys, moving from individual hope to metaphysical despair and finally to a form of non-linear, collective spirituality.

Literary Devices

Forster’s use of literary devices is masterful and central to the novel’s power. He employs rich symbolism with the Marabar Caves, the echo, the sky, and the wasp. He uses biting irony to highlight the hypocrisy of the British, as seen in the failed “Bridge Party” meant to unite the races.

The narrative is driven by a detached, omniscient voice that offers a sense of both realism and profound metaphysical depth. This narrative approach, combined with a keen ear for character and dialogue that feels “overheard,” allows Forster to create a world that is both personal and universal.

3. Themes and Symbolism

The Unknowable: “Muddle” vs. “Mystery”

This is the central philosophical debate of A Passage to India, personified by Fielding’s rationalism and Mrs. Moore’s and Adela’s spiritual crises. Forster suggests that India is not a “mystery” to be solved (as the English might wish) but an unfathomable “muddle,” a chaos that defies Western logic and categories. 12

This distinction is critical: the novel’s power derives from its refusal to neatly define India. This “muddle” is a chaos that can be confusing and disorienting but also a source of life and an alternative to the rigid, form-driven rationalism of the West. It is the backdrop against which the characters’ individual dramas play out, and it is a force that ultimately proves stronger than any of them.

The Marabar Caves and the Echo

The Marabar Caves are the novel’s central symbol, representing the “nothingness and emptiness” at the heart of the universe, a literal “void in the earth” that predates all human history and civilization.13 They are ancient, indifferent, and alien, serving as a metaphysical force that strips away the veneer of human constructs and exposes the deepest psychological truths. The “boum” echo within the caves is a manifestation of this indifference, an anti-sound that negates all moral, religious, and spiritual distinctions, leaving no room for a value system.

For Mrs. Moore, the echo is a spiritual force that “annihilated all sorrow” but also her faith, leading to a profound “spiritual apathy” that consumes her.

For Adela, it is a source of intense psychological trauma that she eventually overcomes by realizing the innocence of Aziz. This contrast symbolizes the distinction between a spiritual collapse and a psychological one, and A Passage to India uses the caves to explore the complex relationship between the two.

4. Genre-Specific Elements

Dialogue as Social Commentary

Dialogue in A Passage to India is not merely a tool for plot advancement; it is a primary vehicle for social and racial commentary. The English characters’ language often reflects their hierarchical and prejudiced worldview. They “pose as gods” and deliver their opinions with a “self-satisfied lilt,” as seen in Ronny Heaslop’s rigid pronouncements on British justice.

In contrast, Aziz’s “impertinent” yet “affectionate” chatter and his frequent use of poetry reveal a character that is romantic and emotionally-driven, traits that are often misunderstood by the English. The clipped, condescending tone of the Anglo-Indians reveals their deep-seated biases, proving that even their casual conversations are infused with the ideology of colonial power.

Subverting Colonial Narratives

While Forster’s A Passage to India has been critiqued for its “Modern Orientalist” tendencies and its portrayal of India as an “Other” , it also subverts traditional colonial narratives that preceded it. Unlike works that presented India as a “savage, disorganized” land in need of British domination, Forster’s novel offers a more nuanced and sympathetic portrayal of the colonized experience.

By focusing on the rich inner lives of his Indian characters and openly critiquing the prejudices and rigidities of the British administration, he challenges the very foundations of the colonial enterprise.14 However, A Passage to India‘s ambivalent stance on Indian nationalism, as noted by critics, suggests that Forster, while sympathetic to the colonized, ultimately fell short of fully condemning either nationalism or colonialism itself.

5. Evaluation, Adaptation, and Personal Insight

1. Evaluation

Strengths/Pleasant/Positive Experiences with Book

The novel’s enduring appeal stems from its profound psychological depth, its unflinching critique of imperial ideology, and its creation of a fictional world that feels both hyper-realistic and metaphysically charged.

The character of Mrs. Moore, in particular, is a literary triumph, embodying a spiritual journey from a simplistic faith to a kind of profound nihilism. The narrative is a powerful examination of the limits of human understanding and the pervasive nature of prejudice.

Weaknesses/Negative Experiences with Book

A contemporary reading, informed by post-colonial theory, reveals some of the novel’s limitations.

Certain Indian characters, like Professor Godbole, can at times feel like “caricatures,” and the novel’s emphasis on India as an inexplicable “muddle” has been criticized as a form of “mystification”.

This perspective suggests that by portraying India as unknowable, Forster neglects to explore its “long traditions of mathematics, science and technology, history, linguistics and jurisprudence,” and instead presents an image of India as a chaos that defies Western logic. It is a vital critical point that should be acknowledged without diminishing the novel’s overall greatness.15

Impact

A Passage to India‘s profound impact is intellectual, emotional, and social. It forces readers to confront how invisible social and political structures shape and constrain personal relationships. The story is a timeless lesson in the dangers of unexamined power, the limitations of rationality, and the enduring human need for connection in a world that is constantly pulling people apart.

It has become a foundational text for post-colonial studies, serving as a benchmark against which other works on the subject are measured.

2. Comparison with Similar Works

A Passage to India stands out from other works of colonial literature, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, by subverting the exoticism and overt racial hierarchies of its contemporaries.

While Conrad and Kipling often exoticized or vilified the colonized “Other,” Forster’s novel focuses on the inner lives of both English and Indian characters, exploring the complex dynamics of their interactions with a rare degree of nuance and sympathy.

It challenges the reader to look beyond simplistic racial and cultural stereotypes and to question the very ideology that underpins the colonial enterprise.

3. Reception and Criticism

Contemporary Reception

Upon its publication in 1924, A Passage to India was an immediate critical success and was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.16 Early critics lauded Forster’s “fairness,” “imagination,” and unique ability to “see and hear internally” the lives of his characters, praising the novel for its sensitive portrayal of a world defined by deep racial divisions.

These critics celebrated the novel as a groundbreaking and highly realistic account of life in British India, written with a “personal impression” that was unburdened by a conscious effort to be fair.6

Modern Criticism

Modern literary critics, however, have re-evaluated the novel through a post-colonial lens. Using the theories of Edward Said, they have analyzed the novel’s portrayals of India as being rooted in “Orientalist” and “hegemonic” discourse.1 Said’s critique, in particular, suggests that while Forster subverted certain colonial views, he ultimately reinforced the idea of a mysterious, unknowable Orient that required the paternalistic control of the West.

The novel’s ambivalent stance on Indian nationalism and its tendency to frame Indians as “the Other” are key points of discussion in modern criticism.

4. Adaptation

Film Adaptation – Comparisons

David Lean’s 1984 film adaptation is widely considered a “faithful” interpretation of the novel’s plot.3 However, the film necessarily struggles to capture the book’s intricate psychological and philosophical dimensions.

For instance, the film must make a definitive choice about what happened in the Marabar Caves, a question that A Passage to India deliberately leaves ambiguous. The psychological collapse of Adela and the profound spiritual crisis of Mrs. Moore, both central to the novel’s core, are inevitably simplified for a visual medium.17

Box Office Information

The 1984 film version of A Passage to India was a modest commercial success. A table of its worldwide box office performance is provided below.

Table 1: Worldwide Box Office Performance: A Passage to India (1984)

| Category | Amount |

| Domestic Gross | $27,187,653 |

| International Gross | $5,818,452 |

| Worldwide Gross | $33,006,105 |

| Production Budget | $27,500,000 |

| Infl. Adj. Dom. BO | $86,859,092 |

The film’s worldwide gross of approximately $33 million against a production budget of $27.5 million indicates a respectable commercial performance for a historical drama released at the time.The domestic opening weekend was modest at $84,580 but its performance grew over its theatrical run, showing strong legs.18

6. Essential Elements and Conclusion

1. Quotable lines/Passage/quotes

- “Because India is part of the earth. And God has put us on earth in order to be pleasant to each other. God… is love.”

- “I do so hate mysteries… I like mysteries but I rather dislike muddles. A mystery is a muddle.”

- “The whole weight of my authority is against it. I have had twenty-five years’ experience of this country… intimacy–never, never.”

- “The sound had spouted after her when she escaped, and was going on still like a river that gradually floods the plain.”

- “The human race would have become a single person centuries ago if marriage was any use.”

- “Nothing embraces the whole of India, nothing, nothing, and that was Akbar’s mistake.”

- “The English are out here to be pleasant.”

- “I have not seen the right places… I have not seen the real India.”

- “Is emotion a sack of potatoes, so much the pound, to be measured out? Am I a machine?”

- “All unfortunate natives are criminals at heart, for the simple reason that they live south of latitude 30.” 25

7. Conclusion

A Passage to India is a powerful and disquieting masterpiece that continues to resonate with readers today. A Passage to India challenges the very idea of a single, unifying truth, suggesting that the human experience is a perpetual negotiation between competing realities.

It is a work of immense intellectual and emotional courage that refuses to offer a simple “passage” to understanding. It is a profound meditation on the legacy of colonialism, a timeless exploration of the human condition, and a literary benchmark against which other works on the subject are measured.

The novel’s greatness lies in its enduring relevance; its themes of racial prejudice, cultural misunderstanding, and the search for identity in a fractured world are as urgent today as they were in 1924. Forster’s masterful portrayal of the complex, contradictory, and often tragic relationship between East and West ensures that A Passage to India will continue to be read, debated, and admired for generations to come.

Works cited

- A Passage to India – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Passage_to_India ↩︎

- A Passage to India by E.M. Forster – Lonesome Reader, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://lonesomereader.com/blog/2024/3/1/a-passage-to-india-by-em-forster ↩︎

- A Passage to India – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Passage_to_India ↩︎

- How does Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism manifest in “The Sign of Four” and “A Passage to India”? – eNotes, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.enotes.com/topics/orientalism/questions/how-edward-saids-theory-orientalism-manifest-1565233 ↩︎

- A Passage to India | British Empire, Colonialism & India | Britannica, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/A-Passage-to-India-novel ↩︎

- do ↩︎

- [Essay] British India: Empire, Ideology & Race — Joseph Barker – New Critique, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://newcritique.co.uk/2015/10/20/essay-british-india-empire-ideology-race-joseph-barker/ ↩︎

- A Passage to India | Classics | The Guardian, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/books/1924/jun/20/classics ↩︎

- A Passage to India: Symbols – SparkNotes, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/passage/symbols/ ↩︎

- A Passage To India Trial and Caves | PDF – Scribd, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/493230839/a-passage-to-India-trial-and-caves ↩︎

- A Passage to India | Classics | The Guardian, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/books/1924/jun/20/classics ↩︎

- How does Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism manifest in “The Sign of Four” and “A Passage to India”? – eNotes, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.enotes.com/topics/orientalism/questions/how-edward-saids-theory-orientalism-manifest-1565233 ↩︎

- Forster’s Vision of the Marabar Caves – Stamford Journal of English, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.banglajol.info/index.php/SJE/article/view/13488/9700 ↩︎

- A Passage to India | Classics | The Guardian, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/books/1924/jun/20/classics ↩︎

- A Passage to India – Wikipedia, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Passage_to_India ↩︎

- do ↩︎

- “A Passage to India”: What is your theory about what truly happened between Adela Quested (Judy Davis) and Dr. Aziz (Victor Banerjee)? : r/movies – Reddit, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/movies/comments/19du3po/a_passage_to_india_what_is_your_theory_about_what/ ↩︎

- A Passage to India (1984) – Box Office and Financial Information – The Numbers, accessed on September 7, 2025, https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Passage-to-India-A ↩︎