Stories don’t only explain a life—they assemble one. Margaret Atwood’s Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts shows readers how to turn scattered memories into meaning without sanding off their edges. A practical problem it solves: how to narrate a complicated, public, creative life truthfully—without pretending the writer has only one self.

Atwood argues that a writer’s life is never a single, seamless thread but a chorus of selves—“the one who lives” and “the one who writes”—and her memoir teaches us how to hold both at once.

Book of Lives is best for readers of literary memoirs; fans of The Handmaid’s Tale/The Testaments; writers craving a candid, witty craft-adjacent autobiography; Canadian literature enthusiasts; anyone fascinated by how childhood ecologies (in Atwood’s case, the Quebec bush) sculpt a voice.

Not for: readers who want a conventional cradle-to-triumph narrative or a step-by-step craft manual; those who prefer linear timelines over layered prequels; readers averse to long books or to autobiographies that debate their own terms.

Table of Contents

1 : Introduction

Margaret Atwood’s Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts (Doubleday, 2025; hardcover ISBN 9780385547512) is the first full memoir from the two-time Booker Prize winner, published in the U.S. by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House.

The book is literary nonfiction—an unconventional, essayistic autobiography—whose chapters often carry “prequel” titles to Atwood’s own novels (Cat’s Eye, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin, The Testaments, and more). The contents list underscores the project’s structure: for instance, “CHAPTER 13 The Handmaid’s Tale, The Prequel,” “CHAPTER 31 Cat’s Eye,” and “CHAPTER 36 The Testaments.”

From the opening pages, Atwood discloses the governing thesis: writers possess a “body double”—a second self that appears the moment writing begins—and any honest memoir has to account for this doubling. “There’s the daily you, and then there’s the other person who does the actual writing. They aren’t the same.”

Atwood sharpens this claim later with the line quoted above—“Every writer is at least two beings”—before detailing how “flow state” and “characters seizing the initiative” complicate simple autobiographical tellings.

2 : Background

Atwood grounds her origin story in a resolutely Canadian setting: a childhood split between Ottawa and remote research stations in the northwestern Quebec forest, where her entomologist father’s work took the family.

The book’s early chapters reconstruct that landscape with diarist precision (“the second-coldest capital city in the world … the first being Ulan Bator,” she notes of Ottawa) and with field-naturalist detail (spruce-bough mattresses, Hudson’s Bay blankets, screened porches to survive blackfly season).

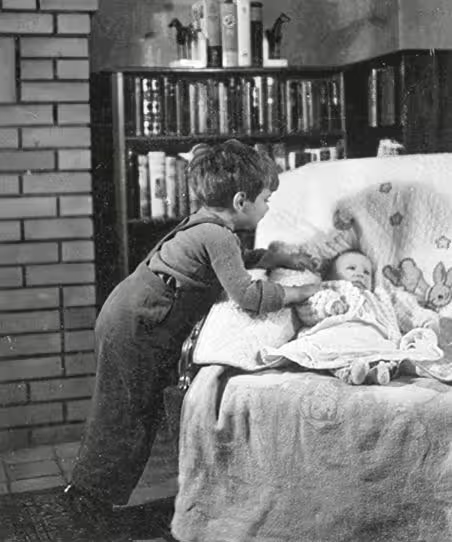

Her mother Margaret’s pragmatic bravery—hauling a newborn into the woods in 1937, cheerfully ignoring city friends who thought she was mad, and preferring “the woods because there was less housework”—becomes part of the book’s thesis about agency and gendered expectations.

Atwood also recounts pre-NHS1-style realities: after her brother’s 1936 birth in Montreal, “they wouldn’t let you out of the hospital until the bill had been paid,” so her father pawned his fountain pen to bring mother and baby home—an anecdote that nails down class, era, and temperament in a few concrete strokes.

3. Book of Lives Summary

Atwood’s memoir is less a straight line than a constellation: each star is a scene, an argument, or a “prequel” to one of her books, and together they map how a writer’s many selves make a life and a literature.

She begins by naming the tension at the core of life-writing—the daily self versus the writing self—and then threads that double helix through childhood in the Quebec bush, the maturation of Canadian publishing, feminist persona-making, craft notes on dystopia, and late-career debates about fairness and due process.

“Every writer is at least two beings: the one who lives, and the one who writes,” she insists, and the entire book shows how those two share one memory but not one voice.

Highlights

• Memoir as doubleness. Atwood formalizes the split between “the one who lives” and “the one who writes,” warning that Q&A sessions engage the former while books emerge from the latter’s deeper “memory bank.”

• Origin scenes → novels. Chapters labeled as “prequels” show how real textures—blackflies, Hudson’s Bay blankets, “franglais,” a baby in a cheesecloth-covered crate—seeded fiction from Cat’s Eye to The Handmaid’s Tale.

• Persona and press. She catalogues caricatures of herself (the “Medusa” hair, the witch, the terrifying interviewer) and flips them with humor: “She writes. Like a man.”

• Becoming a writer, Canadian-style. From hand-glued pamphlets (Double Persephone) to an era when a single journal could review every Canadian poetry/novel title in one roundup, Atwood documents how the country’s literary ecosystem scaled up after 1961.

• How dystopias are built. She coins/rehabilitates “ustopia” (utopia+dystopia), roots The Handmaid’s Tale in American Puritan antecedents, and states why Gilead is a theocracy that distorts scripture.

• Ethical through-line. Even when controversy swirls (e.g., the UBC/Galloway affair), she argues for evidence and process: “there needs to be evidence, and trials, and cross-examinations.”

Detailed Summary

CHAPTER 1 — Farewell to Nova Scotia

The book opens with Atwood looking backward to the East Coast roots that shaped her parents and, through them, her own life. She describes a line of practical, stubborn, wry people and sets the tone for the whole memoir: she won’t draw a single family tree so much as a family “shrub,” with branches that fork, recur, and loop back.

The mood is affectionate but unsentimental; the coast is a place of departures and hard choices. This launching point matters because much of her resilience, humor, and skepticism comes from these people and that place.

CHAPTER 2 — Bush Baby

We move to the woods of Quebec and northern lakes where her entomologist father worked. Water heated in zinc tubs, birds listed by sound, and snakes under stove grates: childhood here is practical, observant, and full of creatures.

Atwood shows how living far from a city sharpened her attention to detail and to the food chain—skills that later feed her fiction and poetry. This chapter builds an origin story for her curiosity: the bush taught her to watch closely and store what she saw.

CHAPTER 3 — Gemini Rising

Atwood is born in 1939, and she has some fun with her horoscope—Gemini with a Scorpio undertow—while acknowledging she’s also shaped by time, place, and family. A page reproduces her natal chart, which she treats both as a joke and a prompt for thinking about doubleness, secrecy, and the split between outer and inner selves—motifs that recur throughout the book.

CHAPTER 4 — Mischiefland

“Mischiefland” is Atwood’s name for that energetic, prank‑filled space of childhood and early teens when rules bend. The chapter gathers stories of DIY theatricals, camp capers, and sly jokes that show her discovering staging, timing, and audience—key tools for a future performer‑writer. It also hints that being playful is a way to test power and manage fear.

These memories foreshadow both her comic streak and her cool eye for consequences. (The memoir later shows this camp‑theatre energy in full bloom.)

CHAPTER 5 — Cat’s Eye, The Prequel

The family finally moves into muddy, half‑finished postwar Toronto. School is a mix of rich and poor; the city is still blue‑law buttoned. The chapter is the seed bed for Cat’s Eye: girlhood hierarchies, awkward friendships, and a watchful, artistic child trying to decode social signals.

She also notes the physical Toronto—brickworks pits, thorny lots—that will reappear as settings in her novels.

CHAPTER 6 — Hallowe’en Baby

This chapter blends memory and motif: Hallowe’en as a family season, a home‑made costume world, and a taste for the uncanny that never quite leaves her work.

In one vivid memory she and her brother craft “Boo Sticks” to scare their mother when conventional trick‑or‑treating isn’t possible—an example of make‑your‑own theatre and myth‑making in miniature.

CHAPTER 7 — Synthesia

Atwood’s teenage years brim with student shows, posters, and the home‑economics operetta Synthesia, in which she plays “Orlon.” The point isn’t self‑glory; it’s that she learns production—how to write, design, and perform as a team. A later photo caption anchors the memory, and the index rows back up how formative these school theatricals were.

CHAPTER 8 — First Snow

A lyric pause: learning to read winter the way her father read tracks—by markings, sounds, and signs. “First Snow” is also a page‑turn toward the private poetry voice: crisp images, loneliness edged with wonder. The chapter shows how seasonal cycles in the bush carved a template for the stripped‑down clarity in her poems.

CHAPTER 9 — The Tragedy of Moonblossom Smith

Summer work at a boys’ camp leads to Atwood’s first original stage confection: an operetta with in‑jokes, broom‑ballets, and a send‑up of tragic romance. It ends like Shakespeare—with the dead popping up for a chorus. The performance teaches her about audience appetite (they loved it) and about how far parody and pastiche can go. It also cements the lifelong habit of channeling a serious subject through comic form.

CHAPTER 10 — Snake Woman

The snakes of her childhood (including those her brother once took to bed) become symbol and story. She later writes a poem called “Snake Woman”; here she connects all the meanings snakes carry—fear and knowledge, danger and transformation—to the way she learned to look inside dark places and keep steady. The theme: what scares you can also teach you.

CHAPTER 11 — The Bohemian Embassy

Toronto’s 1960s coffee‑house scene—steam hissing, toilet flushing mid‑stanza—gives Atwood her first lessons in public reading: hold the room, keep going through interruptions, finish your line. She picks up ballads and bawdy folklore, studies the crowd, and discovers that performance is part of the writer’s job. The chapter doubles as a social snapshot of a pre‑glam literary city making itself up in real time.

CHAPTER 12 — Double Persephone

Atwood’s first book is born the handmade way: she designs, sets, prints, and assembles the poetry chapbook Double Persephone, with collage‑era visual flair. The work is half calling‑card, half apprenticeship—she learns what publishing costs and what it asks. This DIY beginning also forms a habit of caring about covers and typography, which the book’s illustration credits later confirm.

CHAPTER 13 — The Handmaid’s Tale, The Prequel

Decades before The Handmaid’s Tale appears, seeds are already in the ground: a mock‑Latin school joke (“Nolite te bastardes carborundorum”), Puritan reading, dystopias and utopias, and the question of who gets to control women’s lives.

Atwood shows how ideas percolate for years before a novel finds its form. The prequel chapter maps her influences, not plot, and shows how jokes, scripture, and politics simmer together.

CHAPTER 14 — Up in the Air So Blue

Her first novel—unpublished—takes its title from a children’s poem and oscillates between “Then” and “Now.” It’s moody, plot‑light, and ends with the narrator wondering whether to push a boy off a roof—an ending an editor gently advises her to change.

She refuses. The novel never comes out, and she’s grateful later; but writing it teaches structure and stamina, and shows how failure trains a writer’s judgment.

CHAPTER 15 — The Circle Game, The Prequel

As the poems that will become The Circle Game “ooze toward publication,” Atwood falls into a circle of poets and generous mentors. She watches how a creative household runs—children, dock swims, and poems—and realizes a writer’s life can include both work and love. The title idea—games that loop without going anywhere—becomes a way to talk about social patterns, advertising, and gender scripts.

CHAPTER 16 — The Edible Woman

Now comes the first published novel. The office work, the “Men Upstairs” and their surveys, the careful fictions of consumer life—she mines her Canadian Facts job for plot and atmosphere, and sits at the typewriter making both statistics and story.

A woman’s engagement loosens her sense of self until she bakes and eats a cake in her own shape: a sly, comic image of consumption and identity.

CHAPTER 17 — Alias Grace, The Prequel

Before Alias Grace the novel, there is Susanna Moodie and the “red flowers growing out of stones” that poetry opened for her in The Journals of Susanna Moodie. She traces how prose often grows from poetry’s “break,” and how decades of reading about nineteenth‑century Canada, crime, and domestic labor eventually gather into a quilt of voices—Grace Mark’s among them.

CHAPTER 18 — The Animals in That Country

A return to poems: animals as neighbors, warnings, mirrors. The chapter shows how naming and watching animals trains a moral lens—how we treat non‑human life reveals what we are. From child‑time field notes to adult poems, she keeps linking biology to feeling and myth, and the book’s later index confirms the collection’s place in her arc.

CHAPTER 19 — Graeme, The Prequel: Part One

We meet Graeme Gibson before he meets Atwood: a charming Leo with Scorpio rising, a restless mind, a taste for words and woods, and a social world thinly separated from power. These pages read like a novelistic backstory written with love and comic bite. By the end we understand why he and Atwood will fit—shared curiosity, wilderness hunger, and the same appetite for making cultural infrastructure.

CHAPTER 20 — Surfacing

Out of all that comes Surfacing: a novel about wilderness, memory, and shedding false selves. She sketches its editing struggles and the way the north—so central to her upbringing—turns into a story of returning and reckoning. The chapter sits at the pivot where the early books and a lifelong partnership with Graeme tip into a fuller, public author’s life.

CHAPTER 21 — Graeme, The Prequel: Part Two

Gibson moves from young manhood into a writer‑organizer who helps shape Canadian letters; we see the beginnings of his birding passion and the habits of conviviality that later blossom into organizations and observatories. The tone is warm but clear‑eyed—romantic, yes, but also practical about the compromises a literary couple makes.

CHAPTER 22 — The Edibles

“The Edibles” gathers the edible‑image threads from the earlier novel into life: parties, cakes, the way women’s bodies are talked about like desserts, and the way domestic craft can be both pleasure and critique. It’s not a recipe chapter so much as a meditation on how eating, gender, and performance blur.

CHAPTER 23 — Graeme, The Prequel: Part Three

Atwood narrates courtship folding into partnership, and the logistics of two writers living together—money, houses, work rooms, and the timing of a baby. There’s frankness about the complications of previous marriages and divorce delays, but the chapter’s arc points toward a shared creative life anchored by patience and stubbornness.

CHAPTER 24 — Survival

She tells how Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature came to be and how it caught a national nerve. The book’s central image—a survival mindset shaped by climate and history—becomes a way to recognize patterns across Canadian writing. Atwood shows the odd afterlife of criticism that gets taken up as a national mirror.

CHAPTER 25 — Monopoly

This is a story about the short story “Monopoly,” but also about the games of power and chance in publishing, teaching, city life, and relationships. The title doubles as commentary: some people want to corner the board, but the stories show how luck, rules, and players all change mid‑game.

CHAPTER 26 — Lady Oracle

The comic‑gothic novel Lady Oracle arrives amid marriage, moves, and motherhood. Atwood plays with identity masks—costume, romance formulas, and the business of self‑invention—while also managing the very real dailiness of diapers, a farm, and burst‑roof weather. The chapter shows how farce and sincerity can live side by side.

CHAPTER 27 — Days of the Rebels

Her nonfiction Days of the Rebels, 1815–1840 grows from the same appetite for history found in Alias Grace and Survival. She frames political unrest as story: how rebellions shape countries, how documents shape what survives, and how the past constantly interrupts the present.

CHAPTER 28 — Life Before Man

In Life Before Man, she explores fossil rooms, museums, and the chilled interiors of adult relationships. The chapter aligns writing with cataloging—how people store grief and habit like specimens, and how life keeps wriggling under the glass. It’s also about how settings—Toronto neighborhoods, galleries—become characters.

CHAPTER 29 — Bodily Harm

A travel novel about danger and politics becomes a meditation on fear. Atwood explains how experience abroad and news of coups and street violence enter the fiction, but also how writing it clarified the limits of “voyeur” travel. It’s a book about risk—bodily and moral.

CHAPTER 30 — The Handmaid’s Tale

Atwood lays out how Offred got her name (owned “of‑” plus a man’s first name, with a chilling echo of “offered”), why the story is a secret journal smuggled forward, and how speculative fiction works like Verne rather than Wells—what could happen here.

She traces origin sparks from early 1980s politics and conversations with friends who understood authoritarian drift. She also ties settings to Harvard’s bricks and gates—a reinvented Puritan space.

CHAPTER 31 — Cat’s Eye

Returning to Toronto childhood through the painter Elaine, Atwood writes about memory’s traps: what we do to each other as girls, what we forgive, what we can’t. There’s a wry bit on book prizes (the Booker), but the chapter’s heart is the art metaphor—how a painting, like a life, is layers, scrapes, and re‑seeing.

CHAPTER 32 — The Robber Bride

This novel, The Robber Bride, studies female friendship as a gothic caper. Atwood explains Zenia’s magnetism and menace and why the book’s energy is predatory but comic, too. It’s also about the 1990s city—its restaurants, offices, and gossip streams—and about how a trickster figure tests people’s self‑stories.

CHAPTER 33 — Alias Grace

The novel’s patchwork structure—quilts, testimony, rumor—comes into focus. Atwood maps how victorian sources, Susanna Moodie’s pages, and nineteenth‑century medical ideas fed the book. She stresses the moral point that we don’t know the whole truth about Grace Marks; the novel reproduces that uncertainty on purpose.

CHAPTER 34 — The Blind Assassin

A story‑within‑a‑story‑within‑a‑story, this novel, The Blind Assassin, grows out of Atwood’s fascination with pulp sci‑fi, family money, and the unreliable narrator. The chapter links the book’s nested voices to the way memory works—what we tell, what we stage, what we stash. It’s also candid about the oddities of reception and prizes.

CHAPTER 35 — The MaddAddam Trilogy

Origin scene: a 2001 trip to Australia prompts an invasive‑species aha moment; add biotech, climate change, and corporate hubris, and Oryx and Crake begins.

Atwood describes building out Year of the Flood and MaddAddam, even down to cover battles (flying pigoon, open‑beaked raven) and the real people who lent traits to characters. The trilogy is speculative but rooted in what labs can actually do.

CHAPTER 36 — The Testaments

How to return to Gilead decades later? Atwood explains Aunt Lydia’s voice, manuscript theft scares, and editing scrapes. The chapter also remembers the TV era—the handmaids’ red cloaks as protest image—and the uneasy way current politics made the books feel less like warnings and more like mirrors.

CHAPTER 37 — Dearly

Grief enters. After Graeme’s illness and death, Atwood writes Dearly, a poetry book that faces loss with candor, black humor, and tenderness. She quotes or paraphrases lines from “Mr. Lionheart” and other poems that hold the beloved and the absurd at once. The chapter is about love as companionship and about writing when the house is suddenly quiet.

CHAPTER 38 — Old Babes in the Wood

Short stories, Old Babes in the Wood, gather decades of themes—marriage, memory, science, myth—into a late style that is spare and sly. The paired Nell‑and‑Tig stories are the work of someone who has lived long with another mind and is learning to say goodbye. The title nods to fairy tale and forest paths, but the tone is lucid and adult.

CHAPTER 39 — Paper Boat

The closing chapter returns to poetry with Paper Boat. A poem like “Lucky” acknowledges hazard and rescue; the paper boat itself is modest craft—fragile, brave, and buoyed by breath and hands.

Atwood ends on making: even in late life, you fold a page, you set it on the water, and you let it go. It’s a quiet, fitting farewell in which play and peril coexist.

Becoming an Entomologist” (written by Atwood’s father, Carl E. Atwood, and transcribed by Harold Atwood).

Carl sketches his family’s maritime-and-woods lineage—both grandfathers left the sea to farm and log—then his own childhood in rural Nova Scotia: a one-room school, slates, and long walks through forest country.

The turning point is small but decisive: as a barefoot schoolboy he found a giant green cecropia caterpillar, kept it, and watched it become a moth. That single metamorphosis fixed his attention on insects and nudged him toward science—and, as Margaret notes elsewhere, toward the marriage that produced her.

Originally aiming to teach, Carl entered the normal school in Truro, but summer work in field biology and scholarships moved him straight into university: Acadia and then Macdonald College of McGill. He scraped by—plant collecting, tent living, odd jobs—yet kept building scientific skill (he even later donated his duplicate herbarium after a college fire).

A pivotal mentor, Dr. Brittain, shifted Carl from apple-pollen microscopy to the pollinators themselves. In blooming orchards he counted bees, then dug into ground-nesting species (Andrenidae, Halictidae), documenting two forms—queen and worker—sharing the same tunnel in a North American species, a behavior previously unrecorded on this continent.

He published on the observation and on how to distinguish species, and completed his B.Sc. in 1931—the real launch of his life as an entomologist.

In short, the essay is a modest origin story: curiosity, hardship, and mentorship turning a boy’s chance encounter with a caterpillar into a lifelong vocation.

A few cross‑threads that help the whole book “click”

- Childhood attention becomes an adult method. The bush, the birds, the snakes, the careful lists of what lives near the dock—these train the habit of observation that shows up in her fiction’s precise detail and her poems’ sharp images.

- Performance is practice for authorship. From camp operettas to the Bohemian Embassy’s noisy washroom, Atwood learns to hold an audience, improvise, and finish the story even when the espresso machine hisses. Public readings aren’t afterthoughts; they are part of the craft.

- Poetry breaks open; fiction grows from the break. She says this plainly about The Journals of Susanna Moodie and Alias Grace; the pattern repeats elsewhere. Poems work like wedges; novels grow into the wedge’s opening.

- Speculative fiction as “eminently possible.” The Handmaid’s Tale and the MaddAddam books aren’t wild fantasies but thought‑experiments built from what we have already done or could do—technically, legally, or politically. Hence their sting.

- The visuals matter. Atwood designs covers early on and keeps an eye on later ones; the photo section shows her as maker as well as writer (for example, the teen opera Synthesia, the Circle Game cover shoot, and handmaids as protest image).

Final shape of the memoir

Book of Lives refuses a straight “I wrote a book… then another” timeline. Instead, it gives us “prequels” to major works, braided with family stories, jokes, and behind‑the‑scenes episodes.

It reads like the backstage tour of a long theatre run: we see how props (snakes, cakes, pop jingles, Latin mottos) are made, how scenes are blocked (camp stages, coffee houses, book tours), and how a writer keeps her eye on both the world’s cruelties and its absurdities.

The last pages turn back to poems—small boats you fold and release—implying that the making itself is the point, and that a life in words is a life of launching one page after another.

A central corridor in the memoir is the construction of dystopia. She defines “ustopia” as the fusion where every utopia hides a dystopic cost and every dystopia contains a utopian glimmer; she then answers the design question behind The Handmaid’s Tale: if the U.S. went totalitarian, which flag would it wave? Her answer—“a supposedly Christian theocracy” that cherry-picks scripture—is grounded in Puritan continuities: “Nothing comes from nothing.”

Across later chapters, the public figure meets the private ethic. In the UBC/Galloway controversy, she stands on the square of due process, arguing that replacing courts with online pile-ons damages the very people justice is meant to protect; the memoir supplies the key sentence: “there needs to be evidence, and trials, and cross-examinations.”

Finally, by closing with recent books (Dearly, Old Babes in the Wood) and reflective chapters (“Paper Boat”), the memoir loops back to its opening claim: that a writer’s life is a series of threshold crossings—domestic, cultural, imaginative—and that the writing self is the one who keeps the ledger accurately enough to make art and ethically enough to face readers.

Book of Lives Thematic Map

1) Two Selves → One Memory.

Atwood makes a practical claim for how to read an autobiography: treat it as a dialogue between the self who lived and the self who wrote. She explains why the latter cannot stand behind a podium (“no writing is being done at that moment”) and why it can reach further back than the living you.

2) Childhood as Workshop.

The bush-city pendulum and bilingual “border country” produce an ecology of attention: “franglais,” forest fires where “you don’t worry too much about grammar,” and a father learning names for “la machine.” These details aren’t just colorful; they model how to convert material reality into narrative fuel.

3) Feminist Persona, Played with a Wink.

By re-staging sexist optics (hair, witchiness, “bat-flying”), she demonstrates how a writer can refuse a caricature without forfeiting humor. The line “She writes. Like a man.” is both a punchline and a media lesson.

4) Making a National Literature.

The micro-economics of early Canadian writing—in which $0.50 pamphlets sell ~200 copies and one journal surveys all titles—prefigure a decade of rapid institution-building. The memoir thus doubles as cultural history.

5) Designing Dystopia with Receipts.

Atwood’s ustopia framework and Puritan “origin story” explain why Gilead reads as eerily plausible: because it’s layered on older structures (“no country arises from a blank slate”). That design principle—new regimes poured into old molds—recurs throughout.

6) Ethics When the Room is Loud.

Her human-rights instinct (PEN/Amnesty) leads her to press for process even when it costs reputation points. In doing so, she distinguishes courage from tribal loyalty and insists on standards that protect true complaints.

Everything is prequel

Introduction.

A mischievous opening catalogs “images” of Atwood—terrifying interviewer, angel of doom—and proposes a chase scene with her doppelgänger. The joke sets up the serious claim about doubleness that governs the book.

Chs. 1–4: Family formation.

Pre-NHS Montreal: a pawned fountain pen to pay the maternity bill; the move to Ottawa; the pact that he cooks in the bush, she in the city; and the first May 1937 trek into the woods. These mini-epics chart competence, partnership, and appetite for risk.

“Double Persephone,” “The Circle Game,” “The Edible Woman.”

She ties early books to myth and publishing realities: Persephone’s two faces mirror her two selves; the shoestring press run shows the DIY beginnings of a career in a country that told young writers to go elsewhere.

“The Handmaid’s Tale—prequel and after.”

Origin notes, Berlin and Tuscaloosa drafts, the ustopia toolkit, and the decision that an American autocracy would style itself a Bible-quoting theocracy (a point carefully distinguished from “core Christianity”).

Later clusters (“Dearly,” “Old Babes in the Wood,” “Paper Boat”).

Grief, care, and creative stamina are treated without sentimentality; the voice is flinty, funny, alert to cultural noise, and faithful to evidence.

4. What you can take away

- Name your doubles early. If you’re writing about your life, decide when the living self is speaking and when the writing self is—Atwood’s clarity prevents both coyness and confessional overreach.

- Let scenes do the arguing. A cheesecloth-screened baby, an Ottawa museum, a marshaling of “la machine” in a fire—these images are analysis in disguise.

- Treat persona as material, not fate. When culture labels you witch or angel, rewrite the caption. (“She writes. Like a man.”)

- Build worlds on real timbers. Ustopias persuade because they’re poured into old forms; they don’t come from nowhere.

- Hold the ethical line. Popular causes do not eliminate the need for due process; the standard protects truth-tellers and the truth itself.

5 : Critical Analysis

4.1 Evaluation of Content

Atwood’s evidence is lived and archival, but it is also reflexively processed—she shows you the memory and then shows you the literary machine that reshapes it. In the introduction’s hockey-goalie stunt, she uses a body double to dramatize memoir’s fundamental problem: the distance between the performer and the performance, the life and the writing. “The body double appears as soon as you start writing… They aren’t the same.”

That claim is not merely asserted; it structures the entire book. Content chapters function as prequels to earlier works, making a case—sometimes gently, sometimes mischievously—that fiction’s source code is personal history filtered through art.

When a man insists at a reading that “The Handmaid’s Tale is autobiography,” Atwood parries with a paradox that becomes the memoir’s method: outwardly false (she never wore the red robe), inwardly true (everything on the page has “travelled through your head”).

Her style of support is multi-modal. She mixes family lore (the Ottawa apartment smelling of floor wax), sociological observation (Ottawa as bilingual “border country,” the code-switching “franglais”), and macro-cultural history (public schooling and Christian literacy rates in 1961) to contextualize the making of a Canadian writer.

And she advances a gendered media-critique of literary persona with comic bite—cataloguing the hair-based shaming of women writers and the absurd swing between “cookie-baking mum” and “witch.” (“My Medusa eyes go with my Medusa hair,” she quips.) This argument—about how a culture scripts the woman writer—is illustrated with pointed mini-scenes and a tidy one-liner: “She writes. Like a man.”

Finally, Atwood the cultural actor appears: the Oberon Zell-Ravenheart anecdote—copyright, Wiccans, and The Handmaid’s Tale launch optics—reads like a case study in soft power and practical ethics, showing how a world-famous author leverages celebrity to correct a small wrong without fanfare.

Does the book fulfill its purpose?

Yes—because it refuses to pretend memoir is a deposition. Atwood repeatedly tests the line between fact and narrative, and she tells you she’s doing so. The result is an autobiography that treats memory as both evidence and metaphor, which is exactly what a “memoir of sorts” promises

How the argument is supported (logic & evidence):

- Dual-self model (thesis) stated and dramatized—first via the goalie/body-double anecdote, then through the “two beings” passage, and throughout by chapter design.

- Lived data from the 1930s–1970s bush/city oscillations: logistics (trains, tents, mattresses, blackflies), national language policy felt at the family level (“franglais”), and public-education scripture literacy framing 1961 readers—grounding cultural arguments in material specifics.

- Persona analysis backed by period media habits—hair, “witchy” tropes, and 1970s feminist blowback—delivered with verifiable quotes and a satirist’s ear.

Where the book contributes meaningfully:

- To life-writing studies: a working model for writing the self without flattening it.

- To Canadian cultural history: a firsthand account of literary institution-building (the 1960s pivot when Canadian publishing matured), with telling stats and social texture. (“There were so few [books] … it was still possible” for a journal to review every Canadian poetry/novel title in one round-up issue.)

- To feminist criticism: a vivid ledger of how a woman writer is seen, named, policed—and how she jokes back.

6. Reception, criticism

The critical temperature is high. Book Marks aggregates an overall rating of Rave based on early professional reviews, a useful snapshot pointing to consistent praise for wit, candor, and structural play.

The Guardian calls it “less a traditional literary memoir and more a sweeping autobiography,” stressing the tenderness with which she writes about Graeme Gibson and the way childhood bullying channels into fiction like Cat’s Eye.

The Washington Post highlights a humble, unsensational tone and connects the memoir to Atwood’s decades of public engagement (from the LongPen device to environmental activism), reading the book as a study in sustained curiosity and agency.

The Week dubs it “deliciously naughty,” emphasizing its meandering, anecdotal structure and its refusal of tidy redemptive arcs—precisely the feature some readers will love and others might find frustrating.

Canadian and U.K. publishing announcements fix the timeline and scale: February 11, 2025 announcement (McClelland & Stewart, Canada) and November 4, 2025 pub date; U.K. listings confirm Atwood’s recent titles and position the memoir alongside Burning Questions and Old Babes in the Wood in her late-career nonfiction/short-story run.

7 : Comparison with similar other works

If you admired the self-curating candor of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking but wanted more humor and mythic play, Atwood’s Book of Lives will feel like kin. Compared with Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood, Atwood spends less time on pure sensory recall and more time mapping how memories fuel books (those “prequel” chapters).

Readers who loved Karl Ove Knausgård’s maximalist candor may recognize the appetite for totality here, but Atwood’s tone is drier, slyer, and more performatively skeptical of memoir’s truth-claims—she repeatedly reminds you of the body double at work.

Within Atwood’s own oeuvre, it pairs naturally with Burning Questions (essays) and the personal echoes inside Cat’s Eye and Alias Grace. Several chapters explicitly stage those connections—e.g., “Cat’s Eye, The Prequel” and “Alias Grace, The Prequel”—giving longtime readers the source-map they’ve suspected for years.

“From a personal point of view…”

I came to Book of Lives already steeped in Atwood’s world—the dystopias, the backstage essays, the drawings. Reading this memoir felt like walking a familiar city with the author as a slightly wicked tour guide: she points out the alleys you missed, tells you which building used to be a forest, and then admits that sometimes she is not the “she” you think is speaking.

At several points I put the book down just to savor a single, clean sentence—the kind of line that undoes an old assumption with a raised eyebrow. And then, crucially, she brings receipts: dates, places, institutions, even the logistics of tent life and logging booms.

It’s hard to read this book and not feel, in your bones, how a country, a family pact (who cooks in the woods, who in the city), and a set of stubborn curiosities can become literature.

8 : How this book “teaches” memoir

Atwood doesn’t offer a classroom; she offers procedures you can repurpose.

First, name your doubles. By acknowledging the body double early, she frees both selves to speak: the daily one to report, the writing one to shape.

Second, let structure argue. The prequel chapters declare that fiction often starts as a real-life itch, then changes species. The skeptic in the front row who says a dystopia must be autobiography is both wrong (no bonnet) and right (the mind’s materials are yours).

Third, measure culture with small instruments. A pawnbroker’s counter, a screened porch, a franglais phrase in a crisis—precise artifacts anchor sweeping claims about class, climate, and Canadian bilingualism.

Fourth, use humor as x-ray. The Medusa-hair riffs and Oberon Zell mini-saga crack jokes to reveal the power dynamics beneath them (gendered criticism; corporate risk-calculus).

Finally, admit the era’s noise. Whether it’s the 1960s expansion of Canadian publishing or contemporary campus scandals, Atwood refuses storylines that flatter a tribe; she presses for evidence and due process even when it’s inconvenient, which is itself a literary-ethical stance.

9 : What the book feels like to read

Reading Book of Lives is like walking a series of backstage corridors that open into the sets of Atwood’s novels. One door reads “Bush Baby” and you’re suddenly watching a biologist father build a lab of logs while a baby clutches caterpillars; another says “Cat’s Eye, The Prequel” and you’re staring down the origin of a bullying scene disguised as art criticism.

Those scenes are followed—crucially—by explanations of how such moments mutate into fiction or public image. Atwood’s droll inventory of “images” projected onto her—terrifying interviewer, Medusa, feminist scold—shows the persona pressures any woman writer confronts, then flips the script with punchlines that are anecdotes and arguments.

She also logs the domestic contracts and shared labor that underwrote her career (who cooks, where, under what pact), reminding readers that literary history is built from breakfast and firewood as much as from book deals and prizes.

10 : Conclusion

I’d hand Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts to any reader who wants to watch a mind assemble a life honestly—and with mischief.

It’s ideal for general audiences who can enjoy a large, witty story about writing, loving, caregiving, and surviving; it’s also a gift to writers and scholars, because Atwood articulates the split-screen of authorship—how life becomes story, and how story changes life.

When she writes, “The one doing the writing has access to everything in the memory bank,” you feel the exhilaration and the risk of that access—and the book shows her using it responsibly.

If you want to see how a world-famous writer makes a self—out of tents and typewriters, grief and jokes, forests and greenrooms—read this. If you prefer a single voice telling a straight line, this memoir may frustrate you.

But if you want a mind in motion, skeptical of its own stories, delighted by the world’s oddities, and determined to be fair even when it would be easier not to be, you’ll likely finish Book of Lives with a fuller sense of literature—and of life.

Note/s

- The period before the founding of the National Health Service (NHS) in Britain, which was established in 1948 ↩︎