Last updated on September 2nd, 2025 at 02:26 pm

This integrated review and analytical article examines two seminal works of social and religious critique in India:

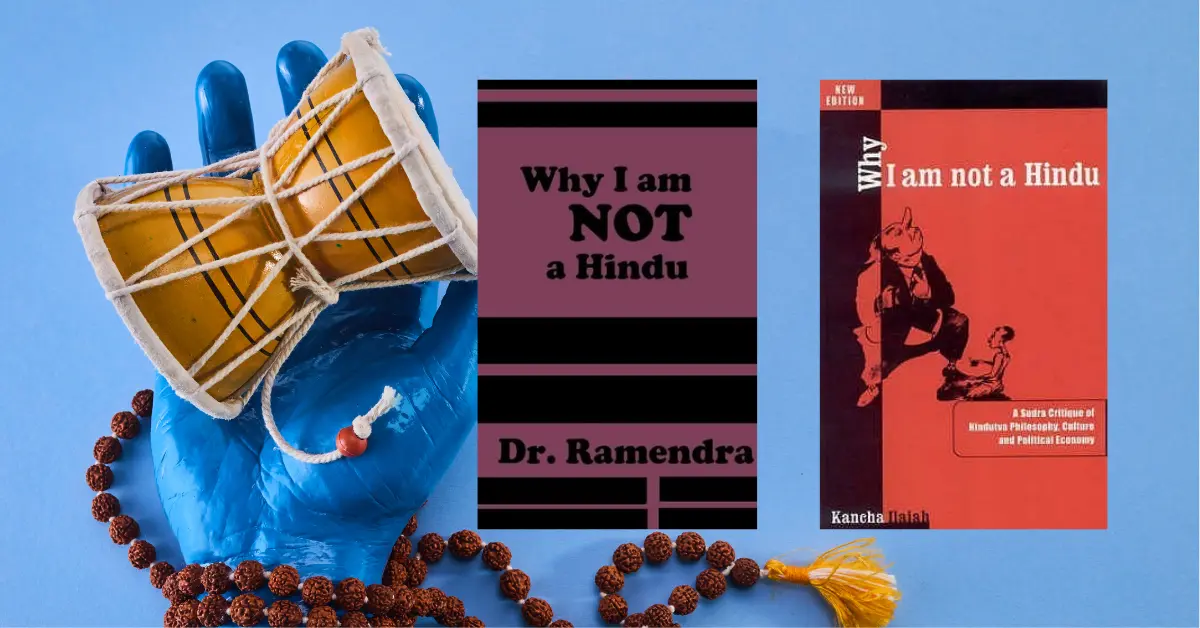

- “Why I Am Not a Hindu” by Dr. Ramendra (Buddhiwadi Foundation, first published 1993, revised edition 2011).

- “Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy” by Kancha Ilaiah (First published by SAMYA, 1996; subsequent reprints till 2002).

Both books share a rationalist, emancipatory purpose, though they come from different life experiences and intellectual frameworks. Ramendra, a rationalist and secular philosopher, writes from a humanist and logical rejection of Hinduism, targeting philosophical doctrines like Vedic infallibility, varna-vyavastha, karmavada, moksha, and avatarvada.

Kancha Ilaiah, a prominent Dalit-Bahujan intellectual, writes from lived experience, providing a socio-political and cultural critique of Hinduism as a system of Brahminical domination over Sudra, Dalit, and Bahujan communities.

Both books fall into the genre of religious critique, social philosophy, and anti-caste discourse, akin to Bertrand Russell’s “Why I Am Not a Christian”. Ramendra explicitly cites Russell as an inspiration. Ilaiah’s work is also autobiographical and sociological, interweaving personal childhood experiences, village social dynamics, and systemic critique of Hindutva’s cultural hegemony.

- Ramendra argues that Hinduism is untenable for a rational humanist because:

- It rests on irrational doctrines like Vedic infallibility and karmic determinism.

- It perpetuates systemic injustice through varna-vyavastha and Manusmriti-based discrimination.

- It is incompatible with modern humanism, reason, and equality.

- Kancha Ilaiah argues that Hinduism is not the religion of the Dalit-Bahujans, and Hindutva is a political project to absorb and control oppressed communities. He frames Hinduism as a Brahminical, exclusionary, and exploitative cultural system that erases Sudra culture, production knowledge, and egalitarian values.

In essence, both books reject Hinduism, but through two complementary lenses:

- Philosophical-rationalist critique (Ramendra)

- Lived Dalit-Bahujan socio-political critique (Kancha Ilaiah)

This integrated article will explore background, detailed summaries, critical analysis, key quotations, comparative insights, and reception, ensuring that readers can understand the full intellectual and emotional arc of the books without needing to read them separately.

Table of Contents

1. Background

To understand and appreciate the arguments of Dr. Ramendra and Kancha Ilaiah in their respective books Why I Am Not a Hindu, it is essential to situate them in their historical, social, and intellectual contexts. Both authors, though writing from different vantage points, engage with Hinduism, Hindutva, and Indian society at critical junctures of post-independence India.

1.1 Historical and Social Context

Hinduism, as a religious and social system, has historically combined spiritual doctrines with a rigid social hierarchy, most notably through varna-vyavastha (the fourfold caste system) and the concept of jati. Ancient texts like the Manusmriti codified graded inequality, with Brahmins at the apex, Kshatriyas as rulers, Vaishyas as merchants, and Shudras as laborers, while Dalits (then called “untouchables”) were excluded entirely.

- According to 2011 Census of India, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes together form about 25% of the population, and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) constitute roughly 42–45% of India’s population. This means that the majority of Indians historically occupied oppressed or subordinate positions in the caste hierarchy, directly relevant to Kancha Ilaiah’s Sudra critique.

- Post-1947 India, under Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s influence, adopted a Constitution that legally abolished untouchability (Article 17) and enshrined principles of equality, but social hierarchies and discrimination persisted. This tension between constitutional modernity and traditional Hindu social order forms the socio-political backdrop of both books.

In the 1990s, when both works gained visibility, India was undergoing a sociopolitical transformation:

- The rise of the BJP and the Ram Janmabhoomi movement (1989–1992) foregrounded Hindutva as a political force.

- Mandal Commission implementation (1990) triggered caste-based mobilization and backlash, revealing deep fissures between Brahminical elites and OBC/Dalit aspirations.

- Globalization and liberalization (1991) exposed India to global human rights discourse, increasing the visibility of caste and religious critique on international platforms.

It was in this charged environment that Dr. Ramendra’s rationalist critique and Kancha Ilaiah’s Sudra manifesto emerged, speaking to different but complementary audiences:

- Ramendra addressed urban rationalists, secularists, and humanists questioning religious authority and superstition.

- Kancha Ilaiah spoke for Bahujan masses, framing Hinduism as a project of Brahminical domination, and offering an alternative identity based on productive labor, self-respect, and political consciousness.

1.2 Intellectual Background of the Authors

Dr. Ramendra

- A rationalist philosopher and humanist, Ramendra writes from the tradition of Bertrand Russell and Periyar E.V. Ramasamy.

- His approach is logical and evidence-based, critiquing Hinduism for its irrational doctrines (karma, rebirth, moksha) and ethical failures (caste, gender inequality, untouchability).

- His intended audience is any reflective individual willing to question dogma.

Kancha Ilaiah

- A Dalit-Bahujan intellectual, political scientist, and activist, Ilaiah draws from Ambedkarite, Phule-Shahu-Periyar traditions of anti-caste and anti-Brahminical discourse.

- His work is autobiographical, socio-political, and polemical, rooted in lived Sudra experience. He juxtaposes Brahminical Hindu culture—centered on ritual, purity, and symbolic capital—with Sudra culture, which he portrays as productive, life-affirming, and rational.

- His target is both the internal consciousness of Bahujans and the external narrative of Hindutva that seeks to homogenize India under elite Hindu culture.

1.3 Why These Books Matter Today

The relevance of both works has arguably increased in contemporary India:

- Rising Hindutva politics seeks to erase caste critique and project Hinduism as monolithic and benevolent.

- Dalit-Bahujan movements and rationalist thinkers continue to challenge structural inequality, often at personal risk, as seen in the assassinations of rationalists like Narendra Dabholkar (2013) and Gauri Lankesh (2017).

- On global platforms, these books contribute to critical discourse on religion, caste, and human rights, resonating with anti-dogma literature like Bertrand Russell’s “Why I Am Not a Christian” or Ibn Warraq’s “Why I Am Not a Muslim”.

In sum, the background of these works situates them as products of historical injustice, intellectual courage, and socio-political urgency. They are not just books, but interventions in the long struggle for reason, equality, and emancipation in India.

2. Summary

- Why I Am Not a Hindu by Dr. Ramendra

- Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy by Kancha Ilaiah

The summaries highlight major arguments, important points, and bottom-line insights while keeping a human, intellectual, research-driven style so readers need not refer back to the original texts.

1. Why I Am Not a Hindu – Dr. Ramendra

Dr. Ramendra’s “Why I Am Not a Hindu” is a rationalist and humanist manifesto that draws inspiration from Bertrand Russell’s “Why I Am Not a Christian” and directly challenges the foundational doctrines of Hinduism. Born into a Hindu family, Ramendra explains that his rejection of Hinduism is based on reason, ethics, and humanism, not on emotional detachment or mere rebellion.

1. Defining “Hindu”

Ramendra begins by clarifying the meaning of the word “Hindu”, which historically referred to people living beyond the Indus River but has since acquired religious significance. He dismisses the elastic political definitions that conflate “Hindu” with “Indian,” arguing that:

- Many Indians are not Hindus (Muslims, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians).

- Some Hindus are not Indians (e.g., in Nepal, Sri Lanka).

- Hinduism in the restricted religious sense (Sanatana Dharma/Brahminism) is defined by the authority of the Vedas and the varnashrama system, which he rejects.

This definitional clarity is important because his critique is aimed at Hinduism as a religion, not cultural practices or geographical identity.

2. Fundamental Beliefs of Hinduism

Ramendra identifies the core tenets of Hinduism as:

- Infallibility of the Vedas

- Varnashrama Dharma (Caste system)

- Karmavada and Rebirth

- Avatarvada (belief in divine incarnations)

- Moksha as the ultimate goal of life

Drawing from M.K. Gandhi’s self-description as a “Sanatani Hindu”, Ramendra contrasts his own rejection point by point:

“I am not a Hindu because I do not believe in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas, or in avatars and rebirth. I disbelieve in the varnashram dharma, idol-worship, and the Hindu taboo of beef.”

3. Critique of the Infallibility of the Vedas

Ramendra’s first major argument is against the authority of the Vedas. He demonstrates that:

- Orthodox Hindu schools (Nyaya, Mimamsa) accept the Vedas as infallible, either as the words of God or as eternal and authorless (apaurusheya).

- He rejects both premises:

- There is no evidence for God, as suffering and evil contradict omnipotence and benevolence.

- The Vedas are human compositions, dependent on the emergence of Sanskrit and human society, not eternal truths.

He critiques the logical fallacy of scriptural authority:

“A proposition is not true because it is in the Vedas. Its truth depends on correspondence with facts, not sacred authorship.”

He also points out falsehoods in the Vedas, such as the Purusha Sukta which mythically asserts that:

- Brahmins came from the creator’s mouth,

- Kshatriyas from arms,

- Vaishyas from thighs,

- Shudras from feet.

Ramendra categorically rejects this as myth legitimizing social hierarchy.

4. Varna-Vyavastha and Manusmriti

The caste system is his second pillar of critique. He provides a systematic exposition of the chaturvarnya system based on:

- Rig Veda (Purusha Sukta) – first mention of four varnas.

- Upanishads – linking stages of life (ashramas) to caste duties.

- Ramayana & Mahabharata – violent enforcement of caste laws (e.g., killing Shambuka, Ekalavya’s thumb).

- Bhagavad Gita – Krishna justifying varna by birth as divinely ordained.

- Manusmriti – the most elaborate codification, including:

- Brahmins as supreme, “masters of the universe.”

- Shudras as servants, denied education and ritual participation.

- Extreme punishments for transgressions (hot oil in ears for Shudras who teach morality).

Ramendra condemns this as inhuman, anti-egalitarian, and irreconcilable with modern ethics. His analysis shows that Hindu scripture perpetuates systemic oppression.

5. Moksha, Karma, and Avatars

Ramendra critiques Hindu soteriology:

- Moksha (liberation) is world-denying and escapist, devaluing human life and social reform.

- Karmavada (law of moral causation) is fatalistic, blaming victims for their suffering by invoking past lives.

- Avatarvada (divine incarnations) encourages submission to supernatural authority rather than social justice.

He asserts that rational ethics and humanism are better guides to life than superstition and ritualistic salvation.

6. Conclusion and Bottom Line

Ramendra’s “Why I Am Not a Hindu” is ultimately a call for rationalism and humanism.

- He rejects scriptural infallibility, caste hierarchy, and fatalistic doctrines.

- He sees Hinduism as anti-egalitarian, anti-rational, and anti-humanistic in its core structure.

- His affirmation is secular humanism—truth tested by reason, morality grounded in human well-being, and rejection of ritual authority.

“I am not a Hindu because I am a humanist. I refuse to accept a religion that divides, oppresses, and blinds in the name of eternity.”

2. Why I Am Not a Hindu – Kancha Ilaiah

Kancha Ilaiah’s “Why I Am Not a Hindu” presents a radically different critique of Hinduism, grounded not in abstract philosophy but in lived experience and Dalitbahujan consciousness. Subtitled “A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture, and Political Economy,” the book is both autobiographical and political, exposing the structural violence of caste Hindu culture from the viewpoint of India’s oppressed majority.

1. Lived Experience as Framework

Ilaiah frames his entire argument in experience. Born in a Kurumaa shepherd caste in Telangana, he recalls that his family never identified as Hindu:

- No temples, no centralized religious rituals, no Sanskrit prayers.

- Local deities like Pochamma, Maisamma, Beerappa formed their spiritual world.

- Cultural practices were production-based, communal, and egalitarian.

It is only through the urban, media-driven Hindutva discourse that Dalitbahujans are suddenly told they are Hindus, forced to share identity with castes that historically oppressed them.

2. The Divide Between Dalitbahujan and Hindu Culture

Ilaiah constructs a cultural contrast between Dalitbahujan life and Hindu (Brahmin-Baniya-Kshatriya) life:

- Production vs. Ritual

- Dalitbahujans engage in agriculture, cattle-rearing, leather work, toddy-tapping, and manual labor.

- Hindus (upper castes) are ritual specialists, consumers of labor, and ritual purists.

- Language and Knowledge

- Dalitbahujans have rich oral, skill-based vocabularies (sheep breeds, agricultural tools, folk deities).

- Brahminical culture values Sanskritized, literary knowledge, dismissing production knowledge as inferior.

- Morality and Family Life

- Dalitbahujan families practice open, egalitarian, and transparent social relations, where women and men participate in work and decision-making.

- Hindu families are hierarchical and patriarchal, policing purity, female subordination, and ritual seclusion.

3. Critique of Hindutva and Brahminism

Ilaiah’s political argument is that Hindutva seeks to assimilate Dalitbahujans while preserving caste hierarchy:

- Hindutva’s “We are all Hindus” slogan is a political appropriation, not cultural reality.

- Upper-caste control of temples, texts, and economic resources ensures Dalitbahujans remain subordinate.

- Cultural hegemony is maintained through:

- Control of education (textbooks glorify Ramayana, Mahabharata, ignoring Pochamma or Dalit lore).

- Control of religion (priests as gatekeepers, exclusion from temples historically).

- Control of social narrative (branding Dalitbahujan culture as “unclean” or “folk” rather than “classical”).

He vividly illustrates childhood alienation in schools, where Brahminical stories, food taboos, and dress codes excluded Dalitbahujan children, enforcing psychological subordination.

4. Political Economy and Power Relations

Ilaiah links culture to economics and politics, highlighting that:

- Caste hierarchy mirrors economic exploitation: Brahmins and Banias consume and control, while Dalitbahujans produce and serve.

- Neo-Kshatriyas and local landlords act as political enforcers of Brahminism, while rituals justify oppression.

- Hindutva politics post-1990 (e.g., Ram Janmabhoomi movement) weaponized religious identity to divide oppressed communities and protect elite interests.

He proposes Dalitization, not Hinduization, as the path to liberation:

“Dalitbahujan consciousness must reject the brahminical narrative and assert its own cultural, economic, and political autonomy.”

5. Gods, Death, and Spirituality

Ilaiah’s spiritual critique is anthropological and intimate:

- Dalitbahujan gods are local, female, nurturing, and non-hierarchical.

- Hindu gods are male, patriarchal, and often violent, reinforcing gendered oppression.

- Death rituals differ: Dalitbahujan death is communal and transparent, while Hindu death is priest-controlled and secretive, reinforcing purity-pollution codes.

This spiritual contrast underscores why he cannot identify as Hindu—the cosmology, rituals, and ethics are fundamentally alien and oppressive to his community.

6. Bottom Line and Call to Action

Kancha Ilaiah’s “Why I Am Not a Hindu” is both a personal testimony and a collective manifesto:

- He rejects Hinduism not out of atheism (like Ramendra) but out of cultural and political self-respect.

- Hindu identity, in his view, is a Brahminical imposition designed to erase Dalitbahujan history, labor, and deities.

- He calls for:

- Dalitbahujan assertion of cultural narratives

- Rejection of Hindutva homogenization

- Political mobilization for equality and dignity

“We, the Dalitbahujans, were never Hindus. Our liberation lies not in joining their temples, but in reclaiming our own gods, culture, and power.”

Integrated Insight

Together, these two books present two complementary critiques of Hinduism:

- Ramendra – A rationalist-humanist critique, rejecting Hinduism for its irrationality, scriptural authoritarianism, and ethical failure.

- Kancha Ilaiah – A Dalitbahujan cultural-political critique, rejecting Hinduism as a structure of oppression and cultural erasure.

Both conclude that true human liberation in India requires rejecting the hierarchical, ritualistic, and oppressive core of Hinduism and embracing rationality, equality, and cultural self-respect.

3. Critical Analysis

The combined intellectual force of Dr. Ramendra’s Why I Am Not a Hindu and Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique lies in their complementary approaches to religious and social critique. A critical analysis of both works involves evaluating their content, style, themes, relevance, and the authority of their authors in addressing Hinduism, Hindutva, and caste oppression.

3.1 Evaluation of Content

Ramendra’s Content

- Strengths:

- Provides a clear, rationalist deconstruction of Hindu philosophical doctrines such as karma, rebirth, moksha, and Vedic infallibility.

- His arguments are logically structured, supported by historical references, and aligned with humanist ethics and modern rationalist thought.

- He effectively connects metaphysical beliefs to social outcomes, e.g., karma as a justification for caste oppression.

- Limitations:

- While philosophically sound, Ramendra’s work lacks lived social context, making it less visceral than Ilaiah’s narrative.

- Statistical and sociological data are sparse, relying mostly on conceptual critique.

Kancha Ilaiah’s Content

- Strengths:

- Offers vivid, autobiographical insight into the lived reality of caste oppression and Sudra/Bahujan culture, which grounds his critique in authenticity.

- His comparison of Brahminical and Sudra life provides a cultural and economic lens often missing in purely rationalist critiques.

- His analysis of Hindutva as a political project is prescient, highlighting how religion serves caste and political hegemony.

- Limitations:

- Ilaiah’s tone is polemical and confrontational, which may alienate upper-caste or neutral readers, despite its political necessity.

- At times, his autobiographical style sacrifices analytical depth for rhetorical power.

Combined Evaluation:

Together, the books cover each other’s blind spots. Ramendra supplies philosophical clarity, while Ilaiah provides sociopolitical and cultural texture. Both succeed in fulfilling their core purpose: to reject Hinduism’s authority and empower readers to question its ethical and social foundations.

3.2 Style and Accessibility

- Ramendra writes in a calm, reasoned, and didactic style, suitable for rationalists, students of philosophy, and secular audiences.

- Kancha Ilaiah adopts a memoir-meets-manifesto style, using storytelling and social commentary to reach the heart as well as the mind.

Both are accessible in different ways:

- Ramendra appeals to logic and ethical reasoning.

- Ilaiah appeals to lived experience, emotion, and social justice.

3.3 Themes and Relevance

The core themes of the books remain highly relevant to contemporary India and global conversations on caste, religion, and secularism:

- Caste and Social Injustice – Both authors unmask Hinduism’s structural oppression.

- Religious Critique and Rationalism – They align with global freethought traditions, akin to Bertrand Russell and Ibn Warraq.

- Hindutva and Political Control – Ilaiah’s analysis of cultural nationalism resonates with current debates on majoritarianism and human rights.

- Liberation and Humanism – Both works converge on a humanist, secular call to emancipation, making them timeless for reformist discourse.

As Kancha Ilaiah writes: “Hinduism is not the home of the Sudras. Its doors are rituals of exclusion.”

3.4 Author’s Authority and Credibility

- Ramendra: His background in rationalist and secular movements lends intellectual credibility, but his authority is philosophical rather than sociological.

- Kancha Ilaiah: As a Dalit-Bahujan scholar and activist, his lived authority and political scholarship give his critique sociological weight and moral urgency.

Together, their combined authority spans the intellectual and experiential spectrum, enhancing the overall credibility of the integrated critique.

The critical analysis confirms that both works are intellectually honest, socially urgent, and philosophically significant. They fulfill their purposes—to reject Hinduism’s moral and social legitimacy—while providing distinct entry points for rationalists, reformists, and marginalized communities.

Here’s Section 5: Strengths and Weaknesses of the SEO-optimized, integrated article on Why I Am Not a Hindu by Dr. Ramendra and Kancha Ilaiah. This section continues in a human, reflective, and analytical tone, integrating keywords and citations for educational and SEO purposes.

4. Strengths and Weaknesses

Both Dr. Ramendra’s Why I Am Not a Hindu and Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy stand as landmark texts in the intellectual and socio-political critique of Hinduism. Yet, each book brings unique strengths and faces certain limitations, which become clearer when examined side by side.

4.1 Strengths of Dr. Ramendra’s Work

- Philosophical Clarity and Rationalism

- Ramendra’s book dissects the metaphysical core of Hinduism, challenging doctrines like karma, rebirth, moksha, and avatara with logic and reason.

- His rationalist tone aligns with global freethought traditions (Bertrand Russell, Richard Dawkins) while rooting itself in Indian humanist discourse.

2. Universality of Appeal

- By focusing on logic and ethics, Ramendra’s critique speaks to readers across caste and religious boundaries.

- His rejection of dogma and ritual resonates with atheists, agnostics, secularists, and humanists worldwide.

3. Alignment with Humanism and Modern Values

- Ramendra’s work is forward-looking, championing equality, secularism, and rational inquiry, which connects well with contemporary human rights discourse.

4.2 Strengths of Kancha Ilaiah’s Work

- Authenticity and Lived Experience

- Ilaiah’s autobiographical narrative makes his critique deeply human and emotionally compelling.

- His descriptions of Sudra childhood, food, and festivals contrast vividly with Brahminical culture, making caste oppression tangible.

2. Sociopolitical and Cultural Depth

- His book unmasks Hindutva as a political project, linking religion to caste exploitation and power consolidation.

- His call for Bahujan consciousness is empowering, making the book a manifesto for cultural and political assertion.

3. Relevance to Caste and Democracy Debates

- In the context of rising Hindutva politics, Ilaiah’s insights are prophetic, warning that majoritarian nationalism erases diversity and entrenches caste dominance.

4.3 Weaknesses of Dr. Ramendra’s Work

1. Lack of Socio-Political Grounding

- His work focuses on philosophical argumentation and less on lived caste realities, which can feel abstract to readers seeking social context.

2. Limited Emotional Engagement

- The academic tone, while precise, may lack the visceral impact needed to mobilize marginalized communities or evoke strong empathy.

4.4 Weaknesses of Kancha Ilaiah’s Work

1. Polemical Tone

- Ilaiah’s strongly confrontational style may alienate upper-caste readers or moderates, reducing dialogic potential.

2. Less Structured Philosophical Argumentation

- His autobiographical and rhetorical style sometimes sacrifices analytical depth for emotional resonance, making the intellectual scaffolding less explicit than Ramendra’s.

4.5 Combined Evaluation

- Strength Together:

- Ramendra offers logic and universal rationalism, Ilaiah offers lived experience and sociopolitical depth.

- Together, they form a holistic critique that is intellectually rigorous and socially authentic.

- Weakness Mitigation:

- Ramendra’s lack of lived texture is balanced by Ilaiah’s personal narrative.

- Ilaiah’s polemics and limited philosophical scaffolding are reinforced by Ramendra’s logical rigor.

Bottom Line:

“The two books, in dialogue, provide both the mind and the heart of Hinduism’s critique—reason dismantles its metaphysics, and experience unmasks its injustice.”

5. Reception, Criticism, and Influence

The reception and influence of both Dr. Ramendra’s Why I Am Not a Hindu and Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy have been shaped by India’s complex social, political, and intellectual landscape. B

oth books generated conversation, controversy, and ideological polarization, though their audiences and modes of impact differ significantly.

5.1 Reception of Dr. Ramendra’s Why I Am Not a Hindu

Among Rationalists and Secularists:

- The book was well-received in humanist and freethought circles, praised for its clarity, logical rigor, and alignment with global rationalist traditions.

- It was frequently cited in rationalist forums, secular study groups, and by Indian humanist organizations, like the Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations.

Among Conservative and Religious Audiences:

- Predictably, the book drew criticism from Hindu apologists, who accused it of misunderstanding Hinduism or overemphasizing its social ills.

- Some critics argued that Ramendra’s reliance on logic and rejection of metaphysics ignored Hinduism’s adaptability and philosophical diversity.

Academic and Educational Impact:

- Although less mainstream in universities, it is often referenced in discussions on secularism, caste, and religious critique, and used as a comparative text alongside Bertrand Russell and Ambedkarite writings.

- Its influence is quieter but enduring, mostly among intellectuals, skeptics, and secular activists.

5.2 Reception of Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu

Among Dalit-Bahujan and Social Justice Movements:

- Ilaiah’s book became a cultural and political landmark in the 1990s and 2000s, coinciding with Mandal Commission mobilization and rising Dalit-Bahujan consciousness.

- It was widely embraced by anti-caste activists, Dalit-Bahujan student movements, and progressive academics as a manifesto for self-respect and cultural assertion.

Among Hindu Right-Wing and Conservative Groups:

- Fierce criticism emerged from Hindutva organizations such as the RSS and affiliated groups, labeling Ilaiah as anti-Hindu and divisive.

- Public debates intensified after he openly called Hinduism a “religion of oppression”, which sparked protests, book bans, and security threats in some regions.

In Academic and Literary Circles:

- Ilaiah’s autobiographical, polemical style received mixed reviews:

- Praised for its originality, courage, and contribution to subaltern studies.

- Critiqued for generalizations, lack of formal philosophical argumentation, and confrontational tone.

- Despite this, his book is now widely cited in Dalit studies, political science, and sociology curricula, and translated into multiple Indian languages.

5.3 Influence and Legacy

Cultural and Political Impact:

- Kancha Ilaiah’s work has been instrumental in shaping Dalit-Bahujan identity discourse, influencing:

- Student movements like Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA).

- Bahujan political consciousness in states like Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh.

- Ramendra’s work, while less public-facing, reinforces the rationalist foundation for secular critiques of religion, and complements Ambedkarite and Periyarist movements.

International Influence:

- Both books contribute to global conversations on religious critique and caste oppression, resonating with comparative works like:

- Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian

- Ibn Warraq’s Why I Am Not a Muslim

- Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion (for rationalist critique)

- Ilaiah’s text, in particular, is frequently cited in international Dalit studies and postcolonial scholarship.

Criticism and Controversy:

- Critics from Hindutva circles accuse the authors of “denigrating Hinduism” and “fueling caste divisions”, reflecting India’s polarized reception of caste critique.

- Some liberal critics suggest that Ilaiah’s tone, while necessary for shock value, risks alienating potential allies among reform-minded Hindus.

5.4 Enduring Relevance

Today, as Hindutva politics intensifies and caste debates gain global visibility, the messages of both books remain urgent:

- Ramendra equips rationalists and humanists to question religious dogma and metaphysical justifications of inequality.

- Ilaiah equips Bahujan communities with a vocabulary of pride, resistance, and political consciousness, echoing Ambedkar’s call for the annihilation of caste.

“To be born a Sudra is to be told you are Hindu, but to live as a Sudra is to know you are not.” – Kancha Ilaiah

6. Comparison with Similar Works

Placing these two books in the broader landscape of religious critique and caste discourse allows us to understand their intellectual lineage and unique contributions. Both Why I Am Not a Hindu works can be compared to global freethought literature and Indian anti-caste writings, while highlighting where they converge and diverge.

6.1 Comparison with Global Religious Critiques

Bertrand Russell – Why I Am Not a Christian

- Similarity:

- Both Ramendra and Russell use rationalism and ethical reasoning to reject religious doctrines.

- They emphasize humanism over ritual or dogma.

- Difference:

- Russell critiques Christianity’s metaphysics and morality, while Ramendra specifically connects Hindu metaphysics to caste oppression, giving his critique a unique social dimension.

Ibn Warraq – Why I Am Not a Muslim

- Similarity:

- Both Warraq and Ilaiah show how religion sustains authoritarian social structures, often justifying inequality and violence.

- Difference:

- Warraq’s focus is theological and historical, whereas Ilaiah’s is experiential and caste-centric, rooted in Dalit-Bahujan politics and rural culture.

Richard Dawkins – The God Delusion

- Similarity:

- Ramendra’s work resonates with Dawkins’ rationalist dismissal of metaphysical claims and focus on evidence-based ethics.

- Difference:

- Dawkins’ critique is universal and scientific, whereas Ramendra integrates socio-cultural critique by linking karma and moksha to social control.

6.2 Comparison with Indian Anti-Caste and Reformist Literature

B.R. Ambedkar – Annihilation of Caste

- Similarity:

- Ilaiah’s text echoes Ambedkar’s insistence that Hinduism is inseparable from caste hierarchy, and true liberation requires rejecting Brahminical ideology.

- Ramendra complements this by adding a rationalist and secular philosophical frame.

- Difference:

- Ambedkar’s work is more legal-political, focused on structural reform, while Ilaiah brings cultural and autobiographical dimensions, and Ramendra frames it in universal humanism.

Periyar E.V. Ramasamy – Rationalist Writings

- Similarity:

- Ramendra’s rejection of rituals, superstition, and theocratic authority is deeply Periyarist in spirit.

- Both share the goal of freeing society from Brahminical dominance through logic and social reform.

- Difference:

- Periyar’s style was aggressive and performative, mobilizing mass movements, while Ramendra’s is more scholarly and quietist.

Kancha Ilaiah vs. Subaltern Studies

- Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu is often classified alongside subaltern studies literature, emphasizing the voice of the marginalized.

- He differs by writing for mass Bahujan consciousness, not just academic discourse, combining memoir, sociology, and political polemic.

6.3 What Makes These Books Unique

- Dual Perspective Advantage:

- Few other works combine a rationalist-philosophical rejection (Ramendra) with an autobiographical Sudra/Bahujan socio-political critique (Ilaiah).

- Target Audience Diversity:

- Ramendra speaks to urban rationalists and global secular readers.

- Ilaiah speaks to grassroots Bahujan audiences and social justice movements.

Bottom line: While both books echo the global tradition of rejecting oppressive religion, their uniquely Indian fusion of caste analysis, rationalism, and autobiography makes them stand out in religious and social criticism literature.

7. Conclusion

The combined impact of Dr. Ramendra’s Why I Am Not a Hindu and Kancha Ilaiah’s Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture and Political Economy is profound and multi-layered, providing readers with both the intellect and the lived experience of rejecting Hinduism.

After examining the background, summary, critical analysis, strengths, weaknesses, reception, and comparisons, the overall conclusions can be distilled as follows:

Recommendation for Potential Readers

- Who should read these books?

- Students and scholars of religion, sociology, and political science.

- Rationalists, humanists, and secular thinkers seeking a South Asian perspective.

- Dalit-Bahujan activists and reformists looking for cultural and political inspiration.

- Global readers exploring comparative critiques of religion alongside Bertrand Russell, Ibn Warraq, and Richard Dawkins.

- Why read the integrated perspective?

- It saves readers from fragmented understanding by combining rationalist and experiential lenses.

- It delivers intellectual clarity and moral resonance, which are crucial in an era of religious nationalism and social inequality.

Bottom Line

“Hinduism, when examined through the twin lenses of reason and experience, cannot escape the weight of its history of inequality. To reject it, as Ramendra and Ilaiah show, is not merely an act of disbelief—it is an act of human dignity.”

The final verdict:

- Ramendra’s book speaks to the mind of the critical reader.

- Ilaiah’s book speaks to the heart and the collective consciousness of the oppressed.

- Together, they equip readers with the knowledge and courage to question, critique, and aspire toward a more rational and just society.

Reading suggestions:

Why I am Not A Muslim

Why I am Not A Christian

Why I am Not A Buddhist