What if a heist didn’t steal a thing but planted it—right in your sleeping mind?

Christopher Nolan’s Inception film is a 2010 science-fiction heist epic that I keep returning to not just for its puzzle box, but for its pulse—its grief, its guilt, its love, and that maddeningly wobbling top.

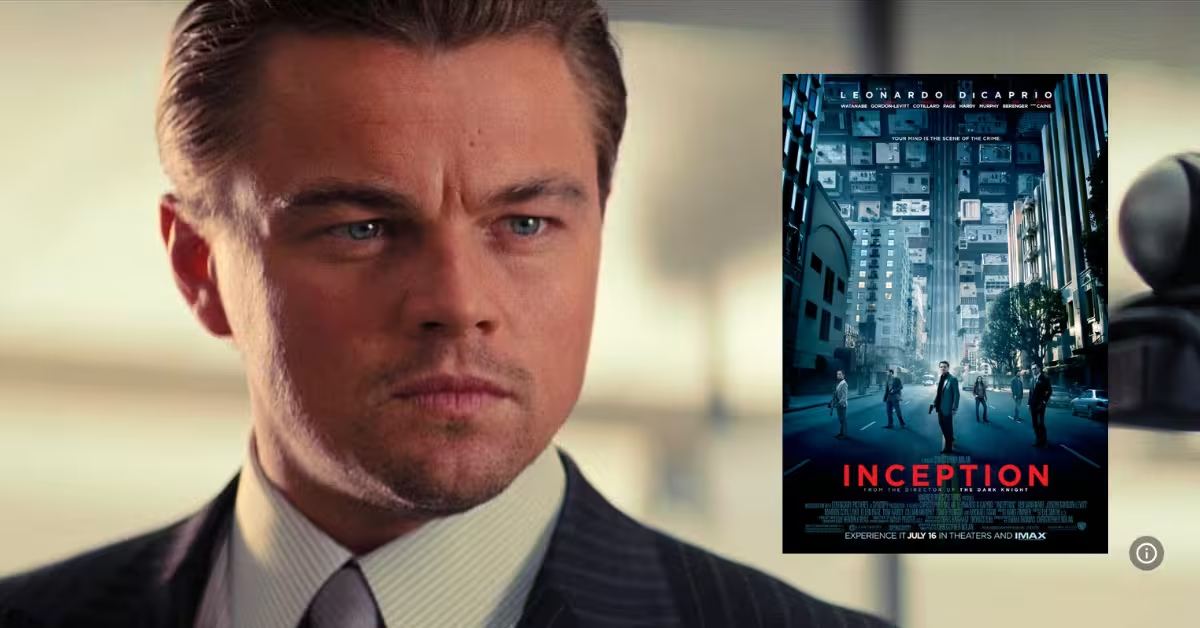

Released worldwide in mid-July 2010, directed and written by Nolan, shot by Wally Pfister, scored by Hans Zimmer, and fronted by Leonardo DiCaprio, the Inception film doesn’t simply depict dreams—it choreographs them like architecture under pressure, a caper threaded through memory’s fault lines.

From the first time I watched the Inception film, I felt its stealth move: it sells you a spectacle, but quietly leaves you with a question about reality that lingers in the body long after the credits.

So here’s my deliberately human take—plain English, personal, and structured section by section—on why the Inception film still matters, what exactly happens (spoilers galore), and how it speaks to how we live, work, and dream now.

Table of Contents

Background

Nolan conceived the Inception film over nearly a decade, sketching a labyrinthine heist set inside shared dreaming while insisting the story anchor to one man’s unresolved grief.

Warner Bros. backed the production with a reported $160 million budget and an extensive international shoot; the Inception film ultimately earned more than $830 million worldwide and won four Oscars (cinematography, sound editing, sound mixing, visual effects), with four more nominations including Best Picture and Original Screenplay.

Critics and audiences embraced the Inception film as a rare blockbuster that’s both cerebral and propulsive—87% on Rotten Tomatoes, a 74 Metascore, and a “B+” CinemaScore—cementing it as one of the enduring hits of the 2010s.

Its cultural footprint widened through endless debates about that final shot, think-pieces on dream science, and interviews where Nolan defended “satisfying ambiguity” rooted in a coherent authorial intent rather than trollish uncertainty.

Plot Summary of Inception

Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) washes onto a beach, dragged before an aged tycoon named Saito, who toys with a spinning top and murmurs about “a half-remembered dream.”

Flash back: Cobb and his partner Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) are expert thieves in an underground trade—extraction—who infiltrate a target’s subconscious during sleep to steal secrets.

They test Saito inside a constructed dream to prove their skill, only for Saito to reveal he engineered the test to recruit them for something harder: inception—planting an idea so the victim believes it’s their own.

The target is Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy), heir to a global energy empire; Saito wants Fischer to break up his late father’s conglomerate to prevent monopoly power.

Cobb agrees because Saito promises to clear his criminal charges in the U.S., where Cobb longs to return to his children.

We learn Cobb is haunted by the projection of his wife Mal (Marion Cotillard), whose volatile presence sabotages missions, because Cobb’s guilt keeps summoning her like a booby-trap from his own subconscious.

To build a crew, Cobb and Arthur recruit Eames (Tom Hardy), a sardonic forger who can assume other identities in dreams; Yusuf (Dileep Rao), a chemist capable of concocting a sedative strong enough for multi-layered dreaming; and Ariadne (Elliot Page), an architect prodigy whom Cobb plucks from a Paris studio to design impossible mazes that can contain Fischer’s defenses.

The rules arrive as brisk, lucid exposition that the Inception film turns into action: dreamers share a portable PASIV device; an architect builds the world; a kick (a sudden drop) wakes you; totems help verify reality; projections are the subject’s subconscious immune system; and if you die under heavy sedation, you don’t wake—you fall into limbo, a raw, unconstructed subconscious space.

Ariadne quickly perceives that Cobb’s secret—Mal—isn’t merely a memory but the residue of a catastrophic earlier experiment; she confronts Cobb after a training run where Mal stabs her, and Cobb finally confesses.

Years ago, he and Mal went too deep for too long, lived decades in shared limbo, built a beautiful city, and grew old together until they killed themselves to return—but not before Cobb committed an unforgivable sin.

To convince Mal to leave limbo, Cobb incepted her with the idea that her world was not real by placing her totem—the spinning top—inside her mental safe so it would never topple.

Back in real life, the idea metastasized: Mal became convinced reality was still a dream and believed only death would wake them; she framed Cobb for her “suicide” to force him to jump, but he refused, and she threw herself from a building.

That guilt—“I was the one who planted the idea in her mind”—is why Mal stalks him as a hostile projection; Ariadne insists she must come along on the real job to keep Cobb honest.

The plan is audacious: stage a three-layer dream within a dream within a dream to “resolve” Fischer’s inherited daddy issues and make him believe disbanding the company is his own liberation.

Layer 1 (the city): Yusuf drives a van through rainy downtown as the team kidnaps Fischer; Eames impersonates Fischer’s godfather, Peter Browning (Tom Berenger), to sow distrust.

But Fischer has been militarized with dream-defense training, so his projections attack; in the firefight, Saito is shot and begins dying, which under the heavy sedative will send him to limbo for an eternity.

The Inception film escalates via physics and timing—Yusuf must keep the van moving to time the kick, while deeper levels must coordinate their own kicks to sync with that falling sensation.

Layer 2 (the hotel): Arthur guides Fischer through a gravity-deaf corridor where the first layer’s van tumble renders the hallway weightless, staging one of cinema’s great action scenes as Arthur tapes everyone together and improvises an elevator-shaft kick.

Here Eames “plays” a helpful advisor who convinces Fischer that Browning is the saboteur, steering Fischer to the idea that his father wanted him to be his own man, the seed that will flower as “break up the empire.”

Layer 3 (the mountain fortress): In a Hoth-like snow citadel, the team storms a high-security vault, with Cobb fighting off Mal’s intrusion—she shoots Fischer in the vault antechamber, jeopardizing everything as a dead Fischer will plummet to limbo.

Ariadne urges a risky pivot: she and Cobb dive to limbo to retrieve Fischer while the others stage synchronized kicks—Yusuf’s van drop, Arthur’s elevator collapse, and Eames’ fortress charges.

Limbo: an endless coastline and a crumbling metropolis Cobb once built with Mal; time dilates to a near-infinite exile, where one can live lifetimes between heartbeats of the top layer.

Cobb finds Saito dying in this wasteland and confronts Mal’s projection in the apartment where they once celebrated an anniversary; Mal begs Cobb to stay, accusing him of choosing a ghost over their “real” marriage, while Ariadne pushes him to let go.

Cobb finally admits his guilt out loud—he planted the fatal doubt inside Mal—and chooses to release her, telling her she’s not real; he allows Ariadne to kick Fischer back up to the snow vault, where Fischer witnesses an imagined, tender scene with his father that reframes the bequest not as domination but as permission.

In the vault, Fischer sees a pinwheel, a childhood token, and hears an internalized benediction: “I was disappointed you tried to be me.” The idea crystallizes as self-definition, not sabotage.

The kicks cascade: the fortress detonates, Arthur’s elevator drops, Yusuf’s van hits the river, and the team surges back through layers like divers breaching into light; Eames revives Fischer, who now believes dissolving the company is the key to freedom.

But Cobb stays behind to honor a promise: find Saito in limbo and remind him they are dreaming so Saito can die there and wake on the plane.

We return to the opening image: an aged Saito spinning the top, recognizing Cobb’s totem, remembering a “leap of faith,” and choosing to pull the trigger so both men can wake.

On the transpacific flight, everyone stirs—Fischer dazed but resolved, Saito calmly dialing a phone, Cobb watching, exhausted and hopeful as they pass through LAX customs unimpeded.

Home at last, Cobb sees his children in the backyard; he places the top on the table and goes to them as the camera lingers on the spinning totem—wobbling—before cutting to black.

The Inception film ends with a paradox both generous and mischievous: not “Is it real?” but “Does it matter?”—Cobb stops checking because he’s chosen his reality.

And that’s the trick—Nolan’s version of an ethical magic act—where the mechanics are available, the path is consistent, but the meaning is left precisely where it should be: with us.

Analysis

1) Direction & Cinematography

Nolan directs the Inception film like a cross-disciplinary architect: narrative time interlocks like Escher stairs, while set-pieces demonstrate rules rather than merely decorate them.

Wally Pfister’s cinematography—a 2011 Oscar winner—balances sleek urban realism (Los Angeles, Tokyo) with grandeur (the snow fortress; the collapsing Paris fold) to keep our bodies believing even when logic bends.

The famously practical rotating hallway fight is more than a stunt; it’s a thesis about physical stakes inside a metaphysical frame, and why the Inception film still feels tactile in an era of weightless CG.

2) Acting Performances

Leonardo DiCaprio grounds the Inception film with a clenched, inward performance—Cobb is all control on the surface, all panic underneath, and the movie’s rhythm follows his guilt.

Marion Cotillard weaponizes warmth into menace; as Mal she’s not a “villain” but a grief-echo, and the chemistry in their limbo scenes gives the heist a tragic undertow.

Around them, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s precision, Tom Hardy’s rakish improvisation, Elliot Page’s moral clarity, and Cillian Murphy’s fragile awakening form the ensemble texture that keeps the Inception film human.

3) Script & Dialogue

Nolan’s screenplay wears its exposition proudly—characters explain as they act—so that the Inception film can sprint without shedding viewers along the way.

If there’s a weakness, it’s the occasional stiffness in quippy exchanges and a schematic neatness in how Fischer’s epiphany arrives; but the clarity is the price of precision, and the trade feels fair.

The pacing, often criticized as relentless, is actually modular: each layer inherits time from the one above, so cross-cutting accelerates emotion even as diegetic time dilates—one of the Inception film’s sly pleasures.

4) Music & Sound Design

Zimmer’s score—in particular “Time”—is the film’s bloodstream, a simple ascending progression swelling like a held breath that finally exhales in the last reel, marrying longing to momentum.

Sound editing and mixing (both Oscar-winning) make the kicks visceral: the slam of the elevator, the plosive shock of the van drop, the muffled crunch of snowfall firefights—each cue becomes a metronome across layers.

The slowed-down Édith Piaf cue is both plot device and meta-joke about time dilation, an aural signature that helps the Inception film synchronize emotion with structure.

5) Themes & Messages

At heart, the Inception film is about authorship: who writes your life—parents, partners, corporations, or you—and what idea you let in as your defining sentence.

It’s also a film about filmmaking: the architect (production designer), the forger (actor), the chemist (projectionist), the extractor (director), and the mark (viewer) entering a dark room to share a constructed dream.

Ambiguity isn’t coyness; it’s empathy—Nolan aligns us with Cobb’s subjective doubt, not to trick us but to honor how perception and desire fuse in grief’s afterglow.

Underneath the spectacle, the Inception film whispers a modern anxiety: that our realities—media feeds, corporate narratives, family legacies—are persistently incepted, and we must build better totems.

Comparison

Among Nolan’s films, the Inception film sits between the moral knottiness of The Dark Knight and the temporal bravura of Dunkirk: less cynical than the former, more emotionally barbed than the latter, and arguably his most complete fusion of blockbuster form with philosophical itch.

Within sci-fi heist cinema, it stands apart from sleek cousins like Heat (procedural rigor) and The Matrix (reality questioning) by insisting that the masterplan is a therapy session; it’s as if Rififi were conducted inside a Jungian lab.

If you’re mapping influences, critics often point to Paprika (dream infiltration), Solaris (grief projections), and even Don Rosa’s Scrooge comic (A Dream of a Lifetime), but the Inception film alchemizes rather than imitates.

Audience Appeal

The Inception film thrills sci-fi fans and cerebral puzzle-solvers, yet it’s surprisingly accessible to casual viewers thanks to clean stakes (go home to your kids) and muscular set-pieces.

Awards followed: four Oscars (with eight total nominations) and significant BAFTA recognition, alongside stout box-office legs—evidence that big-canvas, brainy cinema can crowd the multiplex.

Critics at Rotten Tomatoes call it “smart, innovative, and thrilling,” while Metacritic’s weighted score reflects “generally favorable” consensus—an alignment of prestige and popcorn rare in the 2010s.

Totems, Limbo, Dream Layers, and the Truth About Cobb’s Reality

Inception Ending Explained: The Cruel Ambiguity Debunked — Finally Unravel the Spinning Top’s True Fate

I don’t think the last shot asks “Is it a dream?” so much as “Why does Cobb stop checking?” The camera abandons him to stare at the spinning top—wobbling, yes—but Nolan cuts to black before a verdict. That’s the point: Cobb finally chooses his children over verification. The cruelty isn’t that we don’t know; it’s that certainty was never the prize.

If you need textual evidence, look at how totems are personal. The top belonged to Mal, not Cobb; a totem only works if no one else knows its weight and balance. Cobb co-opts it as a grief ritual, not a reliable instrument. When he walks away, he’s letting the past go. Whether the top falls is less important than the fact that he no longer lets it rule him.

Dreams Within a Dream: The Mind-Bending Layers of Inception Clarified — Master Nolan’s Complex Structure

Think of the movie as a synchronized dive with different time dilations. Level 1 (city/van) runs in minutes, Level 2 (hotel) stretches to hours, Level 3 (mountain) to days, and limbo to near-eternity. Each deeper layer inherits “mass” from the level above, so a single jolt in the van becomes a corridor rotating in the hotel and avalanches in the fortress.

Cross-cutting is the metronome. Kicks must stack—music cue, weightlessness, impact—so the edit can braid parallel climaxes into one coherent crescendo. Once you read the layers as a tempo map, the “confusing” structure snaps into clean cause-and-effect.

Spinning Top Totem: Don’t Be Fooled — Discover the Shocking Clues That Prove Cobb’s Reality

Here’s the heresy: the top can’t prove Cobb’s reality because it’s Mal’s. Totems are only trustworthy if their quirks remain private; everyone, including Cobb, knows how Mal’s top behaves. The more revealing clue is Cobb’s wedding ring—present in dream scenes, absent in waking life—quietly toggling states while the top distracts us.

There’s also the plane landing. Notice the unshowy, practical beats: immigration stamp, father’s friend at arrivals, kids’ slightly older voices. Nolan strips away dream grammar (no impossible geography, no hard cuts through space) to ground the homecoming. The film still withholds certainty, but the mise-en-scène subtly favors reality.

Limbo & Mal’s Story: The Tragic Secrets Behind Cobb’s Guilt — An Emotional and Deep Dive Analysis

Limbo isn’t hell; it’s infinity without architecture. Cobb and Mal colonize it with decades of shared life, then poison it with one “helpful” deception: he plants the idea that their world is fake. Back in reality, the seed keeps growing, and Mal—still convinced she must wake—jumps. Cobb isn’t hunted by a villain; he’s haunted by a consequence.

That’s why Mal’s projection is so fierce. She isn’t a ghost; she’s Cobb’s weaponized self-blame, the saboteur he carries into every mission. In the vault confrontation, releasing Mal is less exorcism than confession: he owns the inception he regrets and accepts he can’t fix the past, only choose differently now.

Christopher Nolan’s Inception: The Visionary Masterpiece That Challenges Everything You Believe About Reality

Nolan stages a philosophical question like a heist because ideas land best when they move. The film’s “real or dream?” hook is a Trojan horse for a kinder challenge: what standards do you use to validate your life, and what happens when those standards become cages?

By insisting on practical effects—the rotating hallway, wire work, location photography—Nolan keeps our bodies convinced while our minds get scrambled. That friction is the miracle: we feel the rules even as we question them.

Reality vs Dream: Afraid You Missed the Truth? Find the Definitive Answer to the Film’s Core Question

Definitive answer: the film denies one. But it gives you a definitive framework. Reality in Inception isn’t proven by props; it’s chosen through commitments. Cobb’s arc moves from compulsive verification to intentional presence. When he stops watching the top, he stops outsourcing meaning to a mechanism.

If you prefer breadcrumbs: the ring theory, the grounded airport sequence, and the absence of dream “tells” in the finale lean real. Still, Nolan preserves a sliver of air—enough for debate, not enough to break the story’s integrity.

Hans Zimmer Inception Music: How the Iconic Score Perfectly Captures the Urgency of The Kick

Zimmer’s score is built like a tide. Tracks such as “Time” ascend by degrees—simple harmony, massive orchestration—mirroring the film’s multi-layer build. The brass swells don’t just decorate action; they compress it, turning cross-cutting into a single held breath.

The famous slowed-down Piaf cue is a structural joke and a serious device: rhythmic markers become wake-up calls. When the kicks stack, percussion tightens and low strings churn, so your pulse syncs to the edit. That’s why the last minutes feel both inevitable and overwhelming.

Ariadne and the Architects: The Untold Power of Creating Worlds — Explore the Brilliant Dream Team

Ariadne isn’t the “sidekick”; she’s the conscience and the engineer. By mapping paradoxes (Penrose stairs, folding Paris) and policing boundaries (“You can’t use memories”), she keeps the mission from collapsing into Cobb’s unresolved grief. Architecture here is ethics with blueprints.

Eames, Arthur, and Yusuf complete the craft guild. Forgery (performance), planning (rules), and chemistry (state control) translate moviemaking into dream-heist mechanics. The subtext couldn’t be clearer: creation is collaborative or it isn’t creation at all.

Corporate Espionage: The Dangerous Game of Inception — Learn the Real-World Threat of Idea Planting

Inception literalizes what branding, propaganda, and disinformation attempt every day: nudge beliefs until the target thinks the conclusion is self-authored. Fischer’s transformation isn’t hypnosis; it’s curated context—framing his father’s legacy so the “break up the empire” idea reads as liberation.

The film’s caution is practical. Guard your “totems” (habits that test reality), audit your inputs, and be skeptical of narratives that slot too perfectly into your desires. If a thought flatters you while asking for nothing, treat it like a forged dream—beautiful, persuasive, and potentially dangerous.

Personal Insight

I return to the Inception film as a manual for living in an attention economy.

Ideas arrive disguised as ours—slogans, memes, survival scripts—and the movie reminds me to audit my inner voice: which thoughts are truly mine, which are inherited, which were planted by well-meaning ghosts.

Cobb’s totem is supposed to prove reality, yet he abandons it at the end, and that’s the lesson I carry—reality isn’t only what can be measured but what you’re willing to stand inside of with your whole self.

The Inception film also reframed creativity for me: a team entering a dream is a filmmaker’s crew invading a blank page, each specialist shaping a world that must withstand scrutiny from hostile projections—doubt, fatigue, deadlines—and the only way out is a synchronized leap.

In a year when attention feels liminal and feeds blur waking from sleeping, I watch the Inception film and treat its rules as hygiene: limit the hostile projections (curate inputs), pick honest architects (collaborators who build constraints), practice kicks (rituals that wake you from spirals), and when faced with the wobble of uncertainty, choose your children—your real commitments—over the seduction of endless verification.

Quotations

“Smart, innovative, and thrilling… the Inception film is that rare summer blockbuster that succeeds viscerally as well as intellectually,” as aggregated at Rotten Tomatoes, gets the balance right.

Peter Travers called it a “wildly ingenious chess game,” while Variety praised “a conceptual tour de force”—phrases that capture both its playful math and its emotional torque.

And Nolan himself has argued that ambiguity must rest on a sincere interpretation, aligning audience uncertainty with Cobb’s own perspective—why the ending lands as earned, not evasive.

Pros and Cons (Bullet Points)

Pros

- Stunning visuals and tactile set-pieces that make the Inception film feel physically real even in fantasy.

- Gripping performances led by DiCaprio and Cotillard, with scene-stealing support from Hardy and Gordon-Levitt.

Cons

- Occasional slow pacing or expository heaviness for viewers craving looser, more character-driven beats.

- Emotional resolution for Fischer can feel schematic despite its elegance.

Conclusion

The Inception film still plays like a dare: believe in a blockbuster smart enough to respect you, brave enough to haunt you, and generous enough to let you decide what’s real.

If you love genre cinema that thinks and feels—thrillers built on ideas as much as impacts—the Inception film is a must-watch, and a must-revisit, because the dream only gets richer when you know the map.

Rating

4.5/5 stars — the Inception film remains a model of mainstream ambition fused with personal obsession.