I still remember the first time City of God film (2002) pinned me to my chair like a sudden squall—urgent, propulsive, and impossibly alive.

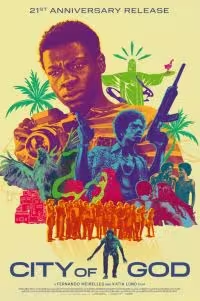

It’s a Brazilian crime drama directed by Fernando Meirelles (with co-direction by Kátia Lund), released in 2002, adapted from Paulo Lins’ novel, and famous for its kinetic storytelling, non-professional cast, and Oscar-nominated craftsmanship; the film opened out of competition at Cannes, grossed over $30.6M worldwide on a ~$3.3M budget, and later earned four Academy Award nominations for Director, Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, and Editing.

For me, its significance isn’t just historical or statistical—it’s visceral; City of God film (2002) reconfigured my sense of what cinematic time can do, how a camera can sprint and still see, and how a narrator can be both witness and survivor.

And right away, that opening knife-on-steel rhythm—chicken, blade, drum—signals a movie that cuts into memory like a scar.

Now, after two decades, the story’s ripples keep widening, with renewed lists and sequel-series conversations reminding us why City of God film (2002) still matters today.

City of God is one of the “101 Best Films You Need to See” on my list

Background

City of God film (2002) adapts Paulo Lins’ semi-autobiographical novel about Cidade de Deus, a Rio de Janeiro housing project seeded in the 1960s; the film tracks how petty hustling metastasized into organized drug warfare across the ’70s and early ’80s, focusing on the divergent paths of the shy, lens-loving Rocket (Buscapé) and the ruthless Li’l Zé (Zé Pequeno).

The production famously recruited a large non-professional cast through acting workshops to capture local cadence, movement, and social texture, and it was shot on 16mm to keep the image grain and speed as nervy as the streets themselves.

As the film traveled, acclaim hardened into canon: Oscar nominations followed in 2004, BAFTA’s win for Editing underscored Daniel Rezende’s dizzying precision, and over the years the film has ranked among the best of the 21st century in BBC, Rolling Stone, and (in 2025) The New York Times critical surveys.

And yes, debate endured as well; some residents and artists argued that global fascination with violence deepened stigma—a conversation any honest reading of City of God film (2002) must keep in frame.

Table of Contents

Plot Summary

A knife clacks, oil spits, and a chicken bolts—that’s the fuse City of God film (2002) lights in its very first minutes.

Then the camera hurtles after it, through alleyways and chords, until the bird lands in a narrow no-man’s-land between a semi-circle of teenage gunmen and a scrawny, wide-eyed boy with a camera; I now know him as Rocket, narrating how he arrived at this absurd, lethal standoff, and why the chicken—like everyone in this neighborhood—has nowhere safe to run.

We cut back to the 1960s, when Cidade de Deus is still new concrete and bright, baked streets—poor, yes, but not yet ruled by cocaine economics; Rocket is a kid with a brother in the semi-legendary Tender Trio—Goose, Shaggy, and Clipper—small-time thieves who rob gas trucks and split the bounty with neighbors as a kind of criminal social welfare.

The Trio’s careful code—no killing, share with the block—doesn’t survive contact with Li’l Dice, a preteen hanger-on whose eyes already glow with predatory calculation; he goads them into a motel stick-up and, in the off-screen chaos that follows, everyone inside is slaughtered, revealing a boundary Dice will never respect and a future violence the Trio never wanted to own.

After the police clamp down, the Tender Trio disintegrates; Shaggy gets shot, Clipper finds religion, and Goose—Rocket’s brother—tries to go straight, only to be gunned down by Li’l Dice in a nighttime ambush that feels both random and grimly inevitable in Cidade de Deus.

By the early 1970s, Li’l Dice has leveled up to Li’l Zé, now running dope corners with a feral smile and a best friend/consigliere named Benny, whose warmth and style make him beloved even as Zé’s sadism makes him feared; together they consolidate power, cleansing rival spots with bullets and fire until drug business maps to Zé’s moods.

But even tyrants need a mirror, and Zé’s comes in the form of Knockout Ned, a handsome, even-tempered bus worker whose life is shredded by Zé’s gang in one spiraling encounter—robbery, assault, the death of a family member—pushing Ned across the Rubicon from civilian to avenger.

From there, City of God film (2002) jumps between rising stakes and ricocheting viewpoints—Rocket’s hustling for a camera and a way out, Ned is training with Carrot (a rival dealer) and learning how vengeance tightens into its own prison, and Benny begins to dream of exit ramps, of a life not measured in turf or corpses.

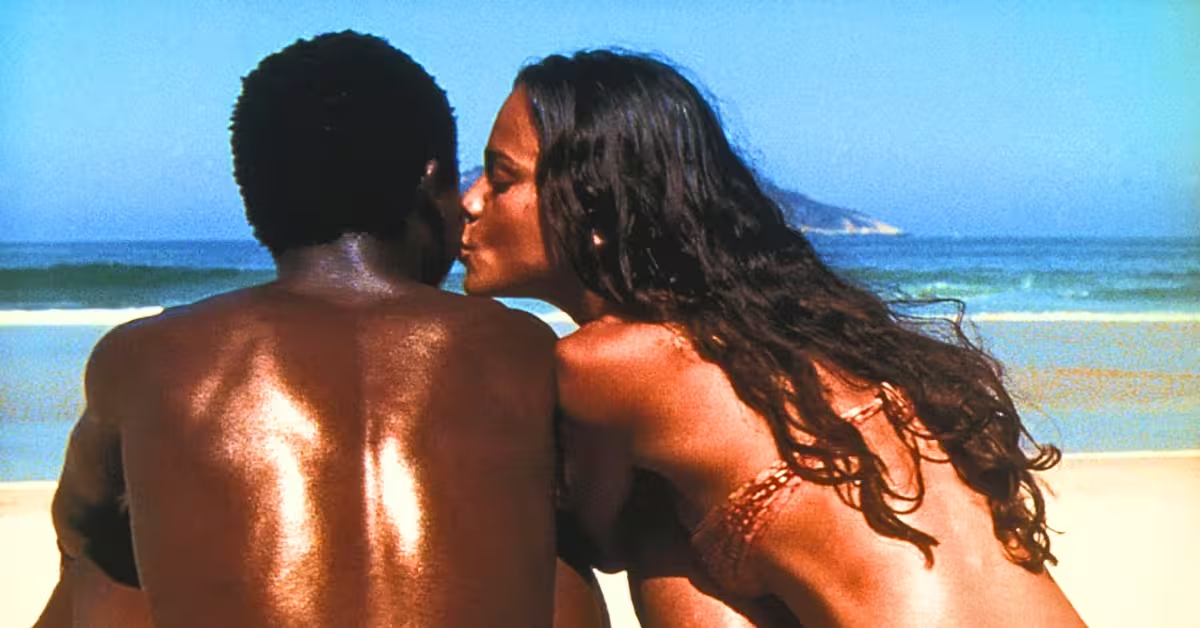

The film’s most bittersweet set-piece hinges on Benny’s farewell party—an orange-gold night swollen with music, dancing, and fragile hope; Zé, drunk on control and jealousy, picks a fight that ends with Benny mistakenly shot dead, and in that instant the City loses its last pressure valve—the one person who could laugh Zé out of his worst impulses.

Grief curdles into a full-scale gang war; Ned’s militia grows, Carrot maneuvers, and the neighborhood becomes a charred chessboard where children patrol with guns nearly as tall as they are—“Runts” who mimic the swagger they see and absorb the rules adults have abandoned.

Parallel to this, Rocket stumbles into journalism almost by accident; when he photographs Zé and his crew, a newspaper publishes his pictures, and instead of being marked for death, Rocket realizes Zé likes the celebrity effect—likes seeing himself mythologized in print, likes the idea that the city beyond the favela whispers his name.

Thus City of God film (2002) pulls off something rare: it shows how media exposure can both protect and endanger, how the gaze of the outside world feeds power even as it documents abuse; Rocket’s “big break” is also a moral crucible—what images will he make public, whom will they wound, what responsibility does he carry once a photo can tilt the balance of fear?

The war crescendos with tactical hits and escalating reprisals—Ned prefers soldierly rules, Zé relishes terror as branding—and the police, corrupt and opportunistic, treat Cidade de Deus not as citizens to protect but as a cashable commodity; payoffs buy time, confiscations bleed gangs of cash, and records vanish in back offices that never learned to keep honest books.

The final movement returns to the opening chicken chase, completing the circle as Rocket gets the shot—the kind of front-page image that could vault him into a newsroom job; he also captures something more explosive: evidence of police corruption, the officers skimming Zé’s stash before quietly releasing him to ensure the cycle continues and the bribe stream flows.

In the public street, a cluster of Runts—kids we’ve watched practicing cruelty on each other—execute Li’l Zé with dozens of shots, a startlingly banal end to a mythic monster; as Zé’s body bleeds into the dirt, Rocket must decide which negatives to print—the dead king that will secure his career or the dirty cops that could end it before it starts.

He chooses the corpse; City of God film (2002) refuses to sanctify or condemn him—Rocket’s choice reads as survivor logic, not sainthood, and in the last beats we see the Runts immediately draft their own kill list, tiny hands already tracing a new map of power.

I’ve always found that closing image—kids planning in a giggly, serious line—more terrifying than Zé’s smile, because it turns a biopic of a tyrant into a portrait of a system, and it leaves me wrestling with the same question every time: how do you break a cycle that keeps recruiting tomorrow’s soldiers from today’s children?

When I revisit City of God film (2002) now, I also notice the way it embeds social detail in throwaway lines and passing shots: the crowded bus routes, the matchbox apartments, the rickety football games, the shirts dyed by dust—all of it textured by César Charlone’s jittery, sun-bleached 16mm palette and Daniel Rezende’s pulse-syncopated edits that make time itself feel elastic and predatory.

To put it simply, the plot of City of God film (2002) is the story of a boy who learns to see—to see danger before it arrives, to see beauty even in the seams of a broken place, and to see a way out that is neither heroic nor pure, merely possible.

And alongside him run the stories of boys who learn to shoot, smile, and command fear before they ever learn to shave, which is why the movie still feels less like fiction and more like a memory someone entrusted to you—messy, breathless, and too urgent to ignore.

Citations used in Installment 1

- Box office and worldwide gross; release context.

- Film overview, awards, production facts (non-professional cast; 16mm), and plot anchors.

- Canonical rankings (BBC, Rolling Stone, NYT 2025) and continuing cultural presence.

- Guardian contemporary review context.

- Community critique (MV Bill).

- Miniseries sequel (2024) note.

Analysis

I think City of God film (2002) remains a masterclass in how style can clarify, not obscure, social reality.

The director Fernando Meirelles, with co-director Kátia Lund, builds a story engine that constantly rewinds and fast-forwards, letting one character’s memory crash into another character’s destiny; that shuffling isn’t a gimmick, it’s the way survival actually feels in a place where yesterday’s grudge is tomorrow’s war.

The editing by Daniel Rezende makes time tactile—cutting faster in moments of panic, loosening when Rocket finds a sliver of quiet—and it’s no accident the film later won the BAFTA Award for Best Editing and scored an Oscar nomination for Rezende’s work.

Meanwhile, César Charlone’s cinematography is jittery and sun-bleached, alive with 16mm grain that doubles as moral texture; the camera runs because the characters run, but it also stops to notice a look, a wall, a child’s tiny hand still gripping a too-big gun. The result is that City of God film (2002) feels both documentary-raw and meticulously composed—an approach that earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography.

1. Direction and Cinematography

Meirelles’ vision, as I read it, is to transfer narrative control to the neighbourhood, letting Rocket narrate like a street historian while the camera treats alleys and courtyards as arteries where information, rumor, and rage circulate.

Charlone’s palette toggles between sweaty daylight and electric nightlife, with practical bulbs flaring in the frame and whip-pans that land as hard as gunshots.

And when the film slows down—Rocket testing a camera, Benny flirting with exit—the compositions square up, as if the world briefly remembers how to breathe before chaos calls it back.

This is why City of God film (2002) doesn’t just “depict” violence; it maps it, shot by shot, showing how power flows through corners, doorways, and faces.

2. Acting Performances

What moves me most is the mixture of non-professional freshness and character specificity: Alexandre Rodrigues plays Rocket with wary curiosity; Leandro Firmino makes Li’l Zé’s grin a weapon; Phellipe and Jonathan Haagensen, Douglas Silva, and Seu Jorge round out a world that feels observed rather than cast.

Because the ensemble is so rooted, small beats—Benny’s laugh, Ned’s reluctant rage—hit like turning points, not just scenes.

And the chemistry works laterally: fear reads on extras’ bodies, awe registers in kids’ eyes, and the camera catches it because City of God film (2002) is always already looking for those changes.

In short, performances in City of God film (2002) convince you you’re not watching actors but neighbors caught between hunger and hope.

3. Script and Dialogue

Bráulio Mantovani’s adaptation takes Paulo Lins’ sprawl and condenses it without flattening; the script nests micro-stories (the Tender Trio, the Runts) inside macro-arcs (Zé’s consolidation, Rocket’s escape), then uses Rocket’s voice to stitch them together.

The dialogue doesn’t chase quotability; it chases cadence—slang, teasing, threats that pivot mid-sentence—so the pacing feels musical even when the content is brutal.

If there’s a “weakness,” it’s only that the structure’s constant momentum can feel relentless, but that relentlessness is the point: City of God film (2002) insists on the moral cost of living in a system that won’t let a sentence end before the next crisis begins.

I never feel the screenplay lecturing me; it shows the logic of each choice until I’m the one asking what I would have done at that corner.

4. Music and Sound Design

The soundtrack swings—samba, funk, parties that grin against poverty—and the sound design is surgical: pans slap, motorbikes buzz, bullets crack dry in the heat.

When City of God film (2002) wants to celebrate, the mix swells; when it wants to scare, it tightens, bringing us closer to breath and footsteps.

That dynamic range makes the big sequences—the motel aftermath, Benny’s farewell—land as emotion, not spectacle, because the sound world has taught us how the favela actually listens to itself.

I love how the score keeps rescuing moments from despair by insisting there’s still music in this place.

5. Themes and Messages

For me, City of God film (2002) is a film about systems—how economics hardens into ethics, how a police ledger becomes a death sentence, how kids inherit roles the way others inherit family silver.

It’s also about seeing: Rocket learns to see as a photographer and as a moral agent, while Zé learns to see himself as legend, which is why the camera and the newspaper become characters in their own right.

And finally, it’s about the recruitment machine—those final Runts drawing up a kill list—asking whether visibility (press, awards, even reviews like this) changes anything downstream or merely feeds the myth until the next boy steps into the crosshairs.

That last image still chills me more than any shootout, because City of God film (2002) closes not with closure but with inheritance.

Comparison

If I line City of God film (2002) up alongside Goodfellas or Gomorrah, the kinship is obvious—propulsive narration, institution-level crime, kinetic cameras—but the divergence is just as clear: this film’s scale is smaller in riches and larger in stakes because children are its raw material.

Compared to Meirelles’ later The Constant Gardener, the visual language overlaps (Charlone’s handheld nerve), but City’s cut-and-thrust is wilder, more collage-like, because the neighborhood isn’t an investigation—it’s a storm you live inside.

And against TV’s The Wire, City of God film (2002) is like a compressed season: the war economy, the politics, the corners, only here the edits do some of the sociology the script doesn’t have time to spell out.

What sets it apart is its moral velocity—how quickly choices calcify into destinies, and how the film refuses to be comforted by its own brilliance.

Audience Appeal / Reception

I’d point crime-drama enthusiasts, world-cinema fans, and cinephiles toward City of God film (2002) in a heartbeat, but I also think casual viewers can ride its momentum; the storytelling is built for human curiosity first, film-school analysis second.

It’s intense, violent, sometimes harrowing; if a friend needs a gentler entry point, I’d steer them to Pixote or La Haine first—then hand them this and say, “Okay, now hold on.”

In terms of reception, the film earned four nominations at the 76th Academy Awards—Director (Meirelles), Adapted Screenplay (Mantovani), Cinematography (Charlone), and Film Editing (Rezende)—and won the BAFTA for Best Editing; box-office totals reached ~$30.7M worldwide, a striking return for a non-English language title, and it continues to rank on 21st-century ‘best of’ lists from BBC, The New York Times (No. 15 in June 2025), and Rolling Stone.

In 2024 the legacy even extended to a sequel miniseries, City of God: The Fight Rages On, set two decades later, which premiered on Max and received mixed-to-average critical scores—an echo that proves how City of God film (2002) keeps generating conversation.

If you ask me whether it’s “for everyone,” I’d say it’s for anyone willing to look squarely at how power grows—and how a camera can be both exit door and mirror.

Personal Insight, today’s lesson

I keep circling back to the journalist’s dilemma in City of God film (2002): What do you publish when publishing changes people’s lives, including your own.

Rocket’s choice—printing the corpse shot, not the police-corruption shot—has always struck me as the film’s quietest and most devastating turn.

Two things make it stick: first, he isn’t sanctified or damned by the movie; second, the system barely notices, because the system is designed to survive both revelation and silence.

When I step out of the theater, I think about how often we confuse exposure with justice, as if seeing were the same as repairing, as if trending were the same as changing.

And then I think of those kids—inheritors of a headline, not beneficiaries of a reform—who will never read the paper Rocket works for and will forever be read by others as statistics.

So what’s the lesson today, outside the screen.

For me it’s this: outcomes require structures, not just stories; yes, stories move us, but unless a story unplugs the way money, guns, and impunity circulate, the machine resets by nightfall.

It also reminds me that craft is ethical, not only aesthetic; when City of God film (2002) chooses to jolt us with a cut or seduce us with a party track, it’s calibrating our attention so we can hold two truths at once—joy persists and danger compounds.

And finally, it’s a reminder to look for exit ramps—people like Benny who dream of leaving and people like Rocket who build a skill that can carry them out; every community has them, and any policy worthy of the word “solution” should multiply them.

On a personal level, I ask myself where I have treated visibility as victory, and where I could invest instead in the quiet, durable reforms—mentors, jobs, clinics, safe transit—that turn “plot twists” into paths.

Quotations

“If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you”—the film’s tagline is melodramatic only until you notice how many characters wake up already cornered.

“You need a photo, kid?” might as well be the movie’s thesis; the camera is both passport and provocation, proof that in City of God film (2002) the act of seeing is never neutral.

Pros and Cons

Pros

- Stunning, kinetic visuals that still serve story and place.

- Gripping performances from a largely non-professional cast.

- Editing that turns time into theme and tension.

- A soundtrack that keeps human joy audible amid fear.

Cons

- Relentless pace can exhaust some viewers.

- Violence and bleakness may overwhelm casual audiences.

Conclusion

When I weigh its craft against its courage, City of God film (2002) still feels necessary.

It’s not “perfect” in the glossy sense; it’s better than that—it’s honest about the cost of survival and precise about how a neighborhood manufactures both heroes and ghosts.

And if you care about cinema that does more than entertain—cinema that argues with you while it dazzles you—this is a must-watch.

Rating

4.5/5 stars—because City of God film (2002) not only changed how I watch crime movies; it changed how I listen to the spaces they happen in.