If your heart rate spikes at a “50% OFF” sign and your budgeting app gathers dust, Confessions of a Shopaholic by Sophie Kinsella is the friendly, hilarious nudge that shows how smart people make silly money choices—and how they grow out of them.

Sophie Kinsella turns debt, denial, and designer cravings into a rom-com about self-awareness: Confessions of a Shopaholic proves that learning to manage money (and identity) is messier—and funnier—than any spreadsheet.

Evidence snapshot: Compulsive buying isn’t a punchline; pooled prevalence sits near 5% of adults across representative studies (4.9%, 95% CI ~3.4–6.9%), with strong heterogeneity across measures, and classic U.S. survey work estimates 5.8%—buyers were far less likely to pay off cards monthly and showed more maladaptive consumer behaviors.

Best for fans of witty, character-driven rom-coms, “chick-lit” with bite, and readers curious about the psychology of spending.

Not for readers seeking gritty literary realism or hard-technical finance manuals—this is warm, satirical fiction with real-world bite.

Introduction

Title and Author Information

- Book: The Secret Dreamworld of a Shopaholic (retitled Confessions of a Shopaholic in the U.S./India)

- Author: Sophie Kinsella (pen name of Madeleine Sophie Wickham)

- Publisher / Pub. details: First UK edition Black Swan / Transworld, 14 September 2000 ; U.S. release under the Confessions title followed in 2001.

Kinsella began as a financial journalist before turning to fiction—useful DNA for a novel poking at the absurdity of money talk.

Filed under comedy / chick lit (literature that appeals mainly to young women), the book landed in the early-2000s wave where female-led, workplace-romcom narratives spoke to ambition, consumption, and identity. Even years later, Kinsella is described as a “quintessential chick-lit writer.”

Confessions of a Shopaholic succeeds because it’s deeper than a spree: beneath the sparkle, it’s a precise social comedy about debt culture and self-deception— buoyed by quotable lines, epistolary bank letters, and a heroine who’s both “irresistibly daft” and painfully relatable.

Table of Contents

1. Background

Set in turn-of-the-millennium London—a time when household debt and consumer credit climbed steeply—Becky Bloomwood’s world reflects a UK economy where household debt and house prices rose substantially from 1987 to 2006; more simply, debt as a share of income surged leading into the 2008 crisis.

Within that culture, Confessions of a Shopaholic follows a financial journalist who can analyze money professionally yet rationalizes purchases personally—exactly the real-world paradox research sees in compulsive buying: high functioning on the surface, problematic outcomes under the hood.

2. Summary of the Book

Plot Overview (spoiler-rich, self-contained)

Rebecca “Becky” Bloomwood lives in Fulham, works at Successful Saving (a consumer-finance magazine), and has a talent for rationalizing purchases she doesn’t need. Kinsella captures this from the jump with irresistible set-pieces and letters from banks that puncture the glamour.

An iconic early image: Becky treats the Financial Times like a fashion accessory—“The FT is by far the best accessory a girl can have,” she declares, extolling its color and the way people “take you seriously” when you carry it. She heads to a Brandon Communications press conference (Luke Brandon’s PR firm), FT tucked under her arm, and is derailed by a siren call in the Denny & George boutique window: a discreet sign—“sale.”

Inside, a shimmering grey-blue scarf—“Reduced from £340 to £120”—rewires her brain in real time. “I have to have this scarf. I have to have it… People will refer to me as the Girl in the Denny and George Scarf.” The card? Back at her desk. Cue frantic bargaining to hold the item until six o’clock and a plan to dash back after the presser.

These scenes rhyme with a deeper cycle: euphoric shopping highs vs. cold-sweat letters from Endwich Bank. A typical missive: “Your unauthorized overdraft is now £3794.56…” signed by Derek Smeath—part bureaucrat, part Greek chorus. Becky tells herself she’ll sort it out “soon”—after a raise that doesn’t come (she’s sent to a unit trust presser instead), after one more “unmissable” deal, after one more white lie.

Kinsella layers set-pieces that build both comic momentum and real stakes: Becky improvises expertise in rooms where jargon outweighs ethics, then flips to heartfelt clarity at unexpected moments. The shopping euphoria is rendered with sensuous accuracy—“That moment… when your fingers curl round the handles of a shiny, uncreased bag… It’s pure, selfish pleasure.” Yet on the way out, a flicker of guilt intrudes: maybe the cash should have gone to something more meaningful.

Orbiting Becky are constants: Suze, her wealthy, warm best friend; Luke Brandon, sharp PR operator whose integrity surprises her; and the relentless paper trail from banks and stores.

The plot arcs toward Becky confronting her rationalizations—the same cycle research on compulsive buying describes: tension, trigger, purchase, temporary relief, negative consequences, renewed tension. (See the 5.8% prevalence study for parallel patterns in repayment and maladaptive behaviors.)

Without stepping beat-by-beat through every comic disaster, the through-line is clear: Becky’s iconic “cut back vs. make more money” dance, her media moments where she accidentally tells the truth beautifully, and a push toward owning her mess in front of people who matter.

If you only read one chapter to “get” the book’s voice, make it the early Denny & George sequence (sale sign → compulsion → logistics farce) and any of the Endwich letters from Derek Smeath—they’re mini-masterclasses in tone and structure.

Setting

London, with its glossy windows and financial districts, isn’t just backdrop—it’s a pressure cooker. Shops like Denny & George and media spaces like Brandon Communications tether Becky’s identity to consumption and image, mirroring a real-world period of surging household credit.

3. Analysis

3.1 Characters

- Becky Bloomwood — a bundle of charm, denial, and genuine moral intuition. She’s not dumb; she’s human, with cognitive dissonance in neon. Her justifications (“it goes with everything,” “investment piece”) are painfully familiar. Her voice spikes with breathless interiority—“I’ll be able to wear it with everything… People will refer to me as the Girl in the Denny and George Scarf.”

- Luke Brandon — not merely a rom-com checkbox; he’s the professional foil whose choices complicate Becky’s worldview (PR gloss vs. substance).

- Suze — the patiently exasperated best friend, a moral mirror.

- Derek Smeath — the personified consequence; his letters punctuate chapters like metronome ticks.

Complexity score: Kinsella writes big comic beats without flattening people. Becky’s arc is incremental, with backslides that feel honest—exactly how behavior change occurs in the literature on compulsive buying.

3.2 Writing Style and Structure

Kinsella blends first-person confessional with epistolary inserts (bank letters, reminders). The humor is observational—“The FT is by far the best accessory a girl can have… people take you seriously”—and the pace alternates sprinting scenes (window-shopping → purchase → fallout) with quieter reckonings.

3.3 Themes and Symbolism

- Identity through consumption: The scarf isn’t cloth; it’s “the Girl in the Denny and George Scarf,” a self she longs to inhabit.

- Pleasure & guilt: The bag-handle moment equated with “the better moments of sex” is comic and true about dopamine.

- Language as camouflage: The FT as “accessory” satirizes both finance and fashion.

- Denial → acceptance: The drumbeat of Derek Smeath letters choreographs Becky’s journey from avoidance to accountability.

3.4 Genre-Specific Elements & Recommendation

As chick lit / rom-com, the book delivers sparkling dialogue, a lovable mess of a heroine, and situational comedy rooted in work and relationships. World-building here is social: shops, brands, TV studios, and PR rooms form a believable ecosystem for status and desire.

Recommend to: readers who enjoyed Bridget Jones’s Diary or The Devil Wears Prada and want humor + heart with a consumer-culture twist. (And to anyone who’s ever justified a “bargain.”)

4. Evaluation

Strengths:

- Voice: Becky’s interior monologue is vivid and quotable.

- Structure: The recurring bank letters are ingenious pacing devices and tonal counterpoints.

- Insight: The book nails the psychology of “I deserve this,” better than many pop-finance guides.

Weaknesses:

- Repetition risk: Some readers may feel the spend-regret cycle repeats one time too many.

- Lightness: Those seeking a darker exploration of addiction might find the comic register too forgiving.

Impact:

Emotionally, you wince because you recognize yourself (or someone you love). Intellectually, it prods reflection: What story do I tell myself when I tap the card?

Comparison with Similar Works

Compared with Bridget Jones’s Diary (social foibles) or The Devil Wears Prada (workplace power), Confessions of a Shopaholic is more explicitly about consumer identity and the math we avoid.

Reception and Criticism

The series has enjoyed broad popularity over time; even later youth-facing reviews cite the books’ “utterly addictive” humor.

Adaptation (Book → Film) & Box Office:

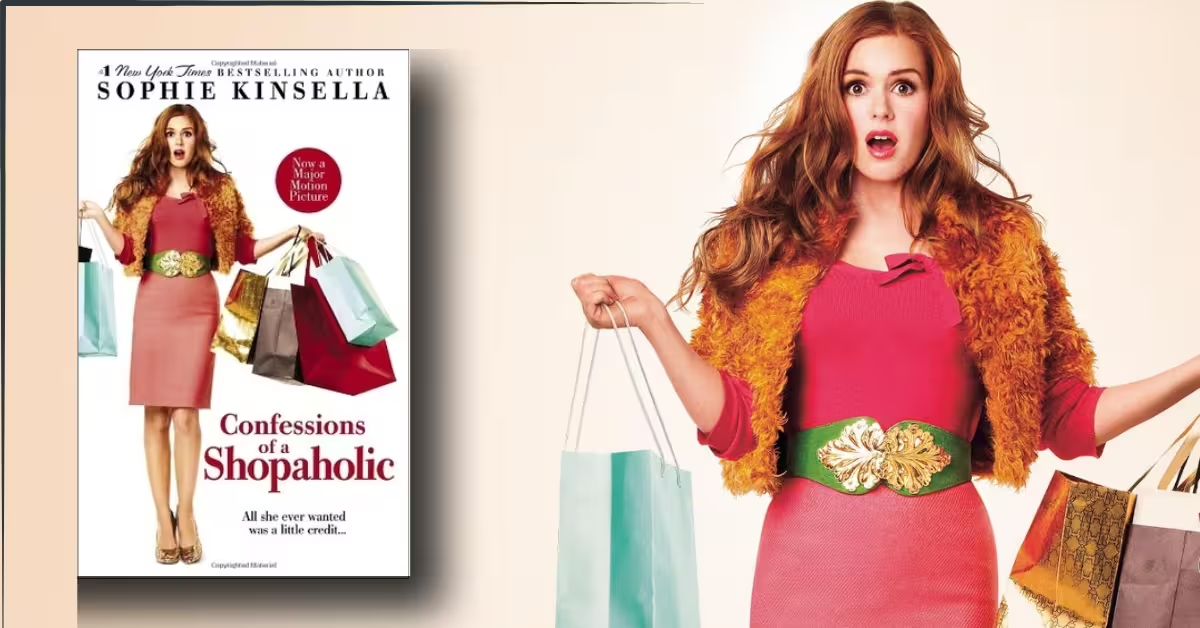

Disney’s 2009 film Confessions of a Shopaholic (dir. P.J. Hogan; Isla Fisher, Hugh Dancy) merges material from the first two books and relocates the story to New York. It earned ~$106.9M worldwide, with critical scores of 26% on Rotten Tomatoes and 38 on Metacritic.

Book vs. film: The novel’s London setting and blue-gray Denny & George scarf become a green scarf in the movie; several side characters are omitted; and the tone is broader, with more overt rom-com beats.

Any notable extras readers may value:

- The book’s chapter-opening bank letters are both a structural gimmick and a thematic drumbeat—an element the film can’t replicate at the same frequency.

- Kinsella shared in 2024 that she has been undergoing treatment for glioblastoma since 2022—a human context that has sparked renewed attention to her body of work.

5. Personal insight and contemporary relevance

Why this matters now:

- Prevalence & behavior: Robust evidence puts compulsive buying near 5% in representative samples; these individuals are far less likely to clear monthly balances and more prone to maladaptive consumer patterns—exactly what Becky dramatizes.

- Macro context: UK data show household debt ballooning from the late 1990s to 2008; reading Confessions of a Shopaholic alongside such trends is a lively way to teach personal finance and behavioral economics (present bias, social signaling).

In a classroom or workshop: Pair excerpts (below) with a quick discussion of the “dopamine loop” of shopping, and ask students to rewrite Becky’s purchase script with a cool-off rule (e.g., 48-hour wait) and a “future self” note. The literature suggests habit change is incremental and cue-based, so design frictions that interrupt the “see-want-tap” chain. Then, map consequences (fees, interest) to narrative beats.

6. Quotable lines

- “The FT is by far the best accessory a girl can have… people take you seriously.”

- “In the window of Denny and George is a discreet sign… sale.”

- “Reduced from £340 to £120.”

- “I have to have this scarf. I have to have it… People will refer to me as the Girl in the Denny and George Scarf.”

- “Your unauthorized overdraft is now £3794.56…” (Endwich Bank, Derek Smeath).

- “That moment… when your fingers curl round the handles of a shiny, uncreased bag… It’s pure, selfish pleasure.”

7. Conclusion

Confessions of a Shopaholic endures because it’s generous to human weakness. It laughs with Becky, not at her, and it quietly suggests that self-knowledge—not shame—is what changes behavior. You get romance, satire, and a behavioral-finance parable in one glossy bag.

Recommendation:

- Definite read for fans of bright, witty, character-first fiction and anyone curious about how money stories shape identity.

- Maybe skip if you need gritty realism or unflinching addiction narratives; this keeps its touch light.

(Side-by-side: Book vs. Film quick table)

- Locale: London (book) → New York (film).

- Signature object: Blue-gray Denny & George scarf (book) → Green scarf (film).

- Structure: Epistolary bank letters drive chapters (book) → Rom-com set-pieces dominate (film).

- Reception: Film scores 26% (RT), 38 (Metacritic) yet crosses $100M worldwide.

8. FAQ

- Why read Confessions of a Shopaholic now?

It’s a funny, humane case study of everyday money psychology that matches modern research on compulsive buying (~5% prevalence). - Is it just about shopping?

No. It’s about identity, self-talk, and how we perform competence while hiding chaos—timeless and relatable. - Series order?

This is Book 1 of the Shopaholic novels, launching Becky’s arc.