If everything you trust—your senses, your memories, even mathematics—could be wrong, what could you still know for sure? Meditations on First Philosophy tackles that nightmare directly: by doubting everything, Descartes rebuilds knowledge from one indestructible point—the thinking self.

By pushing doubt to the limit, Descartes finds one certainty—“I think, therefore I am”—and uses the standard of “clear and distinct” perception (plus proofs of God and the reality of bodies) to anchor a secure framework for knowledge.

Evidence snapshot

- Primary text: Six meditations, framed as a step-by-step retreat from doubt to certainty, followed by a rich set of Objections and Replies from contemporary critics (Hobbes, Gassendi, Arnauld, et al.), which show the arguments under live fire.

- Scholarly consensus: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) treats the method of doubt, the “clear and distinct” criterion, and debates like the Cartesian Circle as central to understanding Descartes’ epistemology.

- Why it still matters: Cambridge University Press calls the Meditations “one of the most widely studied philosophical texts of all time,” a cornerstone of modern philosophy that keeps getting re-translated and taught.

- Classroom data: The Open Syllabus Project (large-scale scrape of university syllabi) ranks canonical philosophy texts among the most-assigned; Meditations regularly appears on philosophy shortlists across departments worldwide.

- Public reach: The theme—“I think, therefore I am”—is explained in popular outlets (e.g., BBC/Radio 4’s History of Ideas features), reflecting continuing cultural relevance. According to BBC-affiliated programming, the cogito remains a go-to entry point for modern philosophy.

Best for-

Readers obsessed with certainty and first principles (STEM people love the rigor).

Students in epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of mind, AI/simulation debates, or history of philosophy needing a compact primary text with centuries of commentary. Anyone wanting the cleanest formulation of methodic doubt and the origin story behind “cogito ergo sum.”

Not for–

Those wanting instant life-hacks; the Meditations is meditative, logical, and sometimes austere. Readers seeking a breezy self-help tone; Descartes is plain and lucid, but he argues carefully and expects focus.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

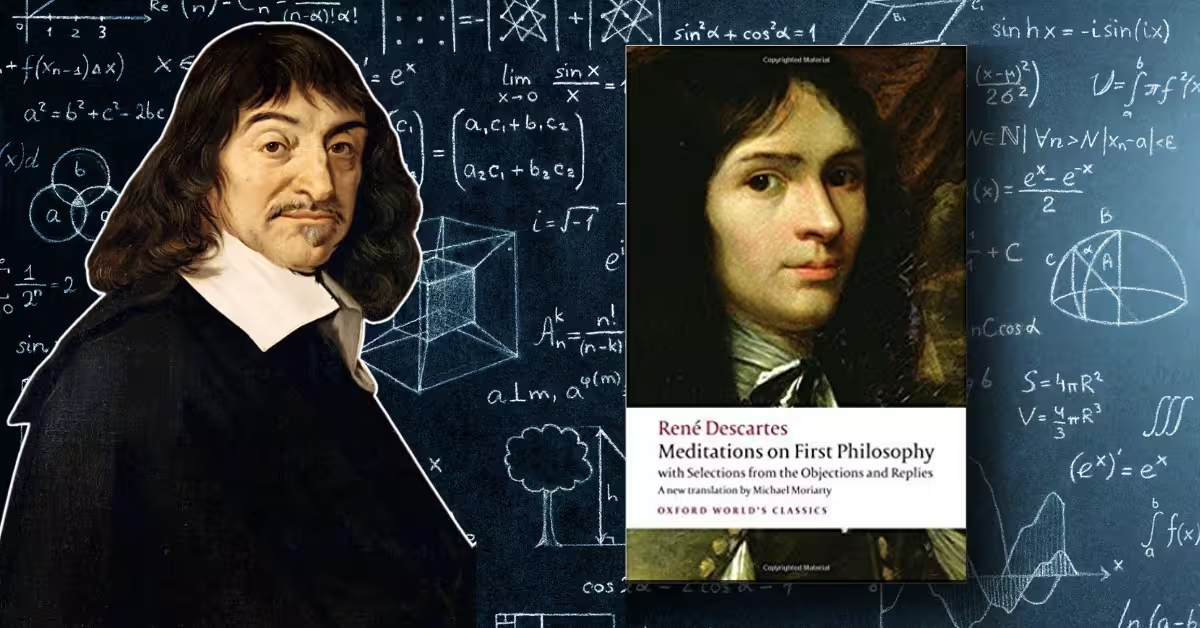

Meditations on First Philosophy (Latin: Meditationes de Prima Philosophia), by René Descartes (1596–1650), first published in 1641 (Latin; French translation 1647). It consists of six meditations and is commonly printed with the Objections and Replies from Descartes’ contemporaries.

The book is early modern metaphysics and epistemology, inaugurating a turn toward first-person certainty and rigorous foundationalism. Descartes, also a mathematician and scientist (analytic geometry, optics), brings an engineer’s precision to philosophy. The six-day meditation format mirrors spiritual exercises but is harnessed to radical philosophical doubt.

Descartes’ central project is to find a foundation for knowledge that cannot be doubted. He accomplishes this by:

- suspending belief in anything dubitable (senses, dreams, even arithmetic under a “malicious demon” hypothesis),

- discovering the indubitable thinking self, and

- arguing that clear and distinct perceptions are true, culminating in proofs of God and the real distinction between mind and body, which also secures the existence of the material world.

2. Background

Meditation structure:

- Doubt everything;

- Find the cogito (“I think—I am”);

- Trace ideas of God and the “light of nature”;

- Diagnose error;

- Re-establish mathematical truths and God’s existence;

- Demonstrate the real distinction of mind and body and the reality of bodies.

- Predecessors & resonances: The idea that self-awareness secures existence has precedents (e.g., Augustine’s “If I am mistaken, I exist”). Descartes’ version, however, is embedded in a systematic method that reboots metaphysics and science.

- Why it’s perennially recommended: Beyond being a pillar of modern philosophy, the Meditations is on “greatest” lists for nonfiction/philosophy and remains a staple in curricula worldwide (teaching data + classic lists). According to long-running canons from major outlets and syllabi analyses, Descartes’ little book reliably anchors any “top philosophy” lineup.

Summary

Synopsis of the Six Following Meditations

Descartes frames the Meditations on First Philosophy (first ed. 1641, second ed. 1642) as a sequenced inquiry—six steps toward certainty—grounded in methodic doubt, the cogito, clear and distinct truth, the existence of God (including an ontological argument), the essence of material things, and the mind–body dualism he famously defends.

Britannica captures the work’s historical profile—publication timeline and the critical Objections and Replies exchange with major contemporaries—while emphasizing that Descartes proceeds by “rejecting as though false all types of belief in which one has ever been, or could ever be, deceived,” a procedure modeled on classical skepticism and Montaigne’s reflections.

Two numerical anchors help: (1) six meditations structure the argument; (2) Descartes advances at least two proofs for God’s existence, including the Fifth Meditation ontological argument that “God necessarily exists” because the idea of a supremely perfect being entails existence. Throughout, he insists that whatever we perceive clearly and distinctly is true; otherwise even the cogito would be doubtful, which it is not.

Descartes himself stresses why this radical doubt is instrumentally valuable: it “delivers us from all prejudices,” leads us away from overreliance on the senses, and guides us to clear and distinct principles that secure truth. As he puts it in the prefatory material, the discipline of doubt helps us “avoid the precipitate judgments” that so often mislead us. In the Synopsis, he also previews pivotal doctrines—e.g., that truth tracks what is clearly and distinctly conceived, and that error arises where the will outreaches the understanding.

Descartes writes-

- “All which we clearly and distinctly perceive is true” (programmatic claim previewed in the synopsis).

- “This doubt … will deliver us from all prejudices” (raison d’être of methodic doubt).

Key takeaways (Synopsis):

- Six-part architecture: methodic doubt → cogito → God → truth & error → essence of material things/ontological argument → existence of material things & mind–body dualism.

- Historical facts: 1641/1642, and the celebrated Objections and Replies exchange.

- Strategic thesis: clear and distinct perception grounds truth; the ontological argument in V crystallizes the rationalist program.

Meditation I : About the Things We May Doubt

Aim. Descartes applies methodic doubt to purge everything that could be even slightly uncertain—sense-derived beliefs, mathematical generalities, and habitual judgments—until only indubitable foundations remain (the future cogito).

He famously dramatizes this by the dream argument and the evil demon hypothesis1. Britannica’s précis tracks the moves: sensory beliefs can mislead (“a square tower appears round from a distance”), dreams can perfectly mimic wakefulness, and even “2 + 3 = 5” might be doubtful if an all-powerful deceiver warped our faculties.

Textual core. Descartes resolves to suspend assent methodically and to keep the discipline vivid against the inertia of habit: he will “become my own deceiver, by supposing, for a time, that all those opinions are entirely false and imaginary,” so that judgment is no longer “turned aside by perverted usage from the path that may conduct to the perception of truth.”

The skeptical endpoint is stark: “there is nothing at all that I formerly believed to be true of which it is impossible to doubt,” and this is not levity but “cogent and maturely considered reasons.”

The most concentrated statement of the evil demon device appears where he imagines:

I know not what being, who is possessed at once of the highest power and the deepest cunning, who is constantly employing all his ingenuity in deceiving me. Doubtless, then, I exist, since am deceived; and, let him deceive me as he may, he can never bring it about that I am nothing, so long as I shall be conscious that I am something. So that it must, in fine, be maintained, all things being maturely and carefully considered, that this proposition (pronunciatum) I am, I exist, is necessarily true each time it is expressed by me, or conceived in my mind.”

—a device that forces even arithmetic and geometry into play as targets of methodic doubt2. And the meditative discipline also warns against relapse: old beliefs “perpetually recur—long and familiar usage giving them the right of occupying my mind.”

He says (Meditation I):

- “I suppose … that all the things which I see are false (fictitious).”

- “There is … a being … of the highest power and the deepest cunning … in deceiving me.”

- “I become my own deceiver, by supposing, for a time, that all those opinions are entirely false and imaginary, until at length, having thus balanced my old by my new prejudices, my judgment shall no longer be turned aside by perverted usage from the path that may conduct to the perception of truth..”

Key takeaways (Meditation I):

- Methodic doubt targets the senses, dreaming, and even mathematics under the evil demon scenario.

- The goal is not skepticism for its own sake but a stable route to clear and distinct truth.

- Practical discipline: resist “familiar usage” that tempts back to unexamined assent.

Meditation II : Of the Nature of the Human Mind

From doubt to the cogito. Pressing the dialectic of the evil demon, Descartes finds an unshakable point: if he is deceived, someone must be there to be deceived.

Hence the indubitable truth cogito—“I am, I exist.” The text states it with exactness: “it must, in fine, be maintained… that this proposition I am, I exist, is necessarily true each time it is expressed by me, or conceived in my mind.” (See also the run-up in the same passage and its Meditation II reprise. ) This is the archetype of a clear and distinct insight.

What the “I” is. Having secured existence, Descartes turns to essence: “What then am I? A thinking thing … that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and also senses and has mental images.” (English tradition summarizes this step crisply.)

The wax argument sharpens the priority of intellect over the senses: the same piece of material wax persists through changes of color, shape, and texture; thus it is grasped “by the intellect alone.” In consequence, “there is nothing more easily or clearly apprehended than my own mind,” because even the recognition of the wax’s identity piggybacks on intellectual judgment.

Descartes makes the point more reflexive: if I judge the wax exists “because I see it,” then a fortiori I exist, since seeing (or seeming to see) presupposes a thinker. “It cannot be that when I see… I myself who think am nothing.” The same reasoning holds if I touch the wax or imagine it—each ostensible route to material things tacitly presumes the thinking subject.

The cogito thus grounds a minimalist essence of self—res cogitans—whose clear and distinct grasp outstrips the body.

Transition to later meditations. The end of II gestures toward a methodological discipline: because it is “difficult to rid oneself” of entrenched opinions, Descartes proposes to “tarry for some time” in the new knowledge and deepen it by meditation.

That stance sets up III–VI: the inquiry into God, truth and error, the ontological argument and the essence of material things, and finally the existence of material things plus the mind–body dualism that closes the sequence.

Descartes puts (Meditation II):

- “I am, I exist … necessarily true each time it is expressed by me.”

- “Bodies … are not properly perceived by the senses … but by the intellect alone.”

- “There is nothing more easily or clearly apprehended than my own mind.”

Key takeaways (Meditation II):

- The cogito is indubitable even under the evil demon hypothesis.

- The essence of the self is thinking (doubting, willing, understanding), grasped clearly and distinctly.

- The wax analysis shows material things are known intellectually; hence the mind is known more surely than body.

Meditation III : Of God: That He Exists

In the third meditation, Descartes turns from the cogito to the source and guarantee of clear and distinct knowledge.

He inventories his ideas (a 3-fold taxonomy: innate, adventitious, and factitious) and introduces the crucial causal rule: an idea’s objective reality must be caused by something with at least as much formal reality.

Since the idea of God presents an infinite, independent, immutable, all-powerful, all-knowing substance, it cannot originate from a finite being like himself.

As he puts it: “By the name God I understand a substance infinite, independent, all-knowing, all-powerful” ; and, given the causal rule, “And thus it is absolutely necessary to conclude…..that God exists: for though the idea of substance be in my mind owing to this, that I myself am a substance, I should not, however, have the idea of an infinite substance, seeing I am a finite being, unless it were given me by some substance in reality infinite. ” . He adds that the divine idea “contains in itself more objective reality than any other” , so only God could be its cause.

Two auxiliary lines appear: (1) the preservation argument (my continued existence, moment to moment, requires a cause with sufficient power), and (2) the degrees of reality (substance › attribute › mode), which shore up the greater-than relation built into the causal principle.

The payoff is epistemic: if an infinite, non-deceiving God exists, then what I perceive clearly and distinctly is true, not by my own lights but because truth’s source is perfect.

Highlights

Three Types of Ideas

Descartes distinguishes three categories of ideas:

- Innate ideas – already present within us by nature.

- Fictitious/Invented ideas – constructed by imagination.

- Adventitious ideas – derived from sensory experiences of the external world.

He insists that the idea of God—a perfect, infinite being—is not adventitious or fictitious, but innate, placed in us by God Himself.

Argument 1: The Causal Adequacy Principle

- Premises:

- Something cannot come from nothing.

- The cause of an idea must have at least as much formal reality (actual existence) as the idea has objective reality (its representational content).

- Steps:

- I possess an idea of God—perfect, infinite, all-knowing.

- This idea has infinite objective reality.

- I cannot be its cause, since I am finite and imperfect.

- Only an infinite and perfect being can cause such an idea.

- Conclusion: Therefore, God exists as the source of this idea.

Because God is by definition perfect, He is also benevolent. Thus, God would not create us to be perpetually deceived. Errors we make must come from misusing our faculties, not from God’s will.

Argument 2: The Cause of My Existence

- Premises:

- I exist. Therefore, there must be a cause of my existence.

- Possible causes considered:

a) Myself (self-creation) – impossible, since I would have made myself perfect.

b) Eternal existence – impossible, as I am contingent and dependent.

c) Parents – leads to infinite regress, since they too need causes.

d) A being less perfect than God – cannot account for the idea of perfection I possess. - Conclusion: The only adequate cause is God.

So, God necessarily exists, sustaining my being moment by moment.

Transition into Meditation IV: The Problem of Error

With “I exist” (cogito) and “God exists” established, a new puzzle arises: If God is good and not a deceiver, how do humans fall into error?

Descartes resolves this by placing humanity on a scale of being between God (infinite perfection) and nothingness. Error is not a positive “thing” created by God but a privation—a lack or imperfection inherent in finite creatures. Our errors stem from the misuse of free will, when it outruns the limits of our understanding.

He summarizes:

- If I suspend judgment when clarity is absent, I do right.

- If I affirm or deny without clear and distinct perception, I misuse my freedom and fall into error.

✅ In essence: Meditation III establishes God’s existence through two main arguments—the causal proof from the idea of God and the proof from the cause of existence. Meditation IV then shows why error exists despite God’s perfection: it arises from our finite nature and the imbalance between limited understanding and unlimited will.

Meditation IV : Of Truth and Error

Having affirmed a non-deceiving God, Descartes confronts the fact that we still err. The diagnosis is elegant: intellect is limited; will is effectively unlimited.

Error occurs when the will outreaches the intellect—that is, when we assent or dissent beyond what we clearly and distinctly understand.

Hence the practical norm: suspend judgment when clarity is missing—“If I abstain from judging…when I do not conceive it with sufficient clearness and distinctness, I act rightly” —because “the knowledge of the understanding ought always to precede the determination of the will” . Misuse of freedom explains error as privation—a lack in us, not a defect in God: “this wrong use of freedom of the will…constitutes the form of error” .

Descartes also notes the cosmological consolation: looking at the whole of creation, apparent defects in parts may fit a perfect totality; thus I should not demand to understand divine purposes in physics , . Practically, he adopts a resolution “never to judge where the truth is not clearly known to me” .

And given that every clear and distinct conception has God as author, “it is necessary to conclude that every such conception…is true” .

Highlights

Key Problem

- If God is perfect and benevolent, why do humans still fall into error?

Great Chain of Being

- God = perfect being, infinite goodness.

- Nothingness = complete absence, ultimate evil.

- Humans = intermediaries between God and nothingness.

- Therefore, error is not a thing created by God, but a privation (a lack of correctness).

Human Position

- As creatures of God, we are not designed to be deceived.

- But because we “participate in nothingness” (limitations), we are prone to mistakes.

- Error = a lack due to our finitude, not a positive gift from God.

Two Concessions

- Limited Knowledge:

- We cannot fully grasp God’s reasons.

- If we had infinite perspective, errors might appear as part of a greater good.

- This challenges Aristotelian “final causes” (explaining things by their purpose), which Descartes rejects.

- Whole vs. Part View:

- Something imperfect in isolation may be perfect in the context of the entire universe.

- Apparent flaws may contribute to overall harmony.

Understanding vs. Free Will

- Understanding: finite, partial, incomplete.

- Will: unlimited, given in full.

- Error arises when will outruns understanding.

Rule for Assent

- If I suspend judgment until I have a clear and distinct grasp, I avoid error.

- If I affirm or deny without clarity, I misuse freedom:

- If false → I clearly err.

- If accidentally true → I am still blameworthy, since judgment lacked clarity.

- Thus, error is my misuse of will, not a fault in God’s gifts.

✅ In short: Error exists not because God deceives us, but because we, as finite beings with limited understanding and unlimited will, sometimes judge beyond what we know clearly. Error is a privation, not a positive reality.

Revision Chart — Meditation IV: Source of Error and Human Responsibility

| Category | Explanation | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Error | Error is not a “thing” created by God but a privation (absence of correctness). Humans, as intermediaries between God (perfection) and nothingness, naturally lack completeness. | Error = lack due to finitude, not deception from God. |

| Why Error is Allowed by God | 1. Limited knowledge: we cannot comprehend God’s infinite reasons. What seems like error may be good in a broader view.2. Whole vs. part: an apparent flaw in isolation may contribute to the harmony of the universe. | God remains benevolent; error is consistent with divine perfection. |

| Human Responsibility | Humans have finite understanding but unlimited free will. Error occurs when will outruns understanding. | Misuse of will causes error—not God’s design. |

| Rule for Assent | Only assent to what is clear and distinct. Suspend judgment if clarity is absent.- If I affirm what is false → clear error.- If I affirm without clarity but hit truth → still blameworthy, since judgment was rash. | Clarity first, judgment second. |

| Overall Lesson | God gave two good gifts: understanding (limited) and will (complete). Their imbalance explains error. | Use will wisely: only judge what is clear and distinct. |

Meditation V : Of the Essence of Material Things; and, Once More, of God, that He Exists

Descartes now broadens the inventory of clear and distinct content to cover the essences of material things as mathematics presents them: extension in length, breadth, depth; figure, motion, number.

Such properties and their theorems are discovered rather than invented: with a triangle, “its three angles are equal to two right [angles]…which…cannot be said to have been invented by me” . These immutable natures are “not framed by me,” but have a “fixed…essence…immutable and eternal” . That is the essence side.

Then comes the second proof of God—the ontological argument. From the innate idea of a supremely perfect being, Descartes argues that existence belongs to God’s essence as necessarily as two right angles belong to the triangle: “existence can no more be separated from the essence of God than the idea of a mountain from that of a valley” (with the triangle analogy at ). He explicitly sets the standard: the certainty of God’s existence is “at least as certain” as truths of mathematics .

By pairing geometrical essences (of material things) with the ontological necessity of God, he tightens the bridge from clear and distinct ideas to reality: mathematical content is true because what is clearly and distinctly conceived is authored by God. (Background note: later critics dub a tension here the Cartesian circle; Descartes insists the light of nature already warrants clarity, while God’s non-deception secures its infallibility. For the standard presentation, see Britannica’s synopsis .)

Highlights

Core Aim

- Purpose: Extend the scope of known truths (beyond self and God) toward material things.

- But Descartes postpones direct proof of external objects until Meditation VI; first, he considers the ideas of these objects.

Clear vs. Confused Ideas

- Clear and distinct ideas: extension, duration, motion.

- These are mathematical/geometrical in nature.

- Cannot be altered without contradiction (e.g., a triangle’s internal angles must equal 180°).

- Confused or obscure ideas: imaginative combinations (e.g., mythical creatures).

- Their properties can be arbitrarily invented.

- Insight: Mathematical truths have their own immutable essence, independent of the thinker.

Immutable Natures

- We have in ourselves innumerable ideas of things.

- Even if no such objects exist outside us, the ideas have fixed, eternal essences not produced by us.

- Example: the idea of a triangle remains eternal, immutable, and objective—even if no actual triangle exists.

Ontological Argument for God

- Realization: the idea of God is as clear as mathematical truths.

- Logical proof (adapted from St. Anselm):

- God = an infinitely perfect being.

- Perfection includes existence.

- Therefore, God necessarily exists.

- Analogy: Just as one cannot conceive of a mountain without a valley, one cannot conceive of God without existence.

Epistemic Significance

- God’s existence is confirmed not only by earlier causal arguments but also by this ontological proof.

- With a perfect God as guarantor, the criterion of clarity and distinctness is fully secure.

- Without the knowledge of a perfect God, no truth could be assured.

- Descartes: “The certainty and truth of all my knowledge derives from one thing: my thought of the true God. Before I knew Him, I couldn’t know anything else perfectly.”

✅ In short: Meditation V emphasizes that mathematical essences (extension, motion, number) are immutable and independent of the mind, and then advances the ontological argument: existence belongs to God’s essence. With this established, all clear and distinct truths—including mathematical ones—rest firmly on God’s perfection and non-deceptiveness.

Meditation VI : Of the Existence of Material Things, and the Real Distinction between Soul and Body

The final meditation secures material things and the mind–body dualism. First, Descartes argues that the faculty of imagination points toward something extended (imagination works by “turning to” images), suggesting a body-side correlate.

More decisively, God is no deceiver: my strong natural inclination to believe in an external world would be inexplicable if no material world existed. Therefore, material things exist—at least as extended substances with mathematically specifiable properties.

He then distinguishes sensation’s functional role from its representational accuracy. Color, taste, heat and the like do not necessarily resemble qualities in bodies; they are modes of thinking that register the mind–body union.

He cautions that we often mistake habit for nature (e.g., that a hot object “contains” our idea of heat, or that distant towers match their visual appearance), and clarifies what “nature teaches” in this narrower sense—what belongs to the composite of mind and body , .

On the real distinction, he argues: what can be clearly and distinctly conceived apart can exist apart. Since I clearly conceive mind (a thinking, unextended thing) without body, and body (an extended, non-thinking thing) without mind, they are really distinct. He also notes an asymmetry of divisibility: bodies are divisible; minds are not—“we are not able to conceive the half of a mind” .

Yet Descartes stresses the substantial union of the two: I am not a mere pilot in a ship. If I were, pains would be reported to me intellectually, but in fact pain, hunger, thirst are “confused modes of thinking” that disclose the union and apparent fusion of mind and body . This dual message—real distinction plus intimate union—both grounds modern mind–body dualism and anticipates later worries about interaction.

Highlights

Possibility of Material Things

- Material things are possible because God can create whatever is clearly and distinctly conceived.

- Mathematics shows such essences (extension, figure, motion) can exist, since they are grasped without contradiction.

Imagination vs. Understanding

- Imagination = mind’s eye “looking at” an image (e.g., picturing the three lines of a triangle).

- Understanding = intellectual grasp without imagery (e.g., knowing what a chiliagon is but not picturing 1,000 sides).

- Imagination requires a special mental effort, proving it is distinct from pure intellect.

- This suggests that imagination is linked to the body, while understanding belongs to the mind.

Proof of Mind–Body Distinction

- God can create whatever is clearly and distinctly conceived.

- I clearly conceive of myself as a thinking thing (res cogitans) independent of body.

- I clearly conceive of body as an extended thing (res extensa) independent of mind.

- Therefore, mind and body are distinct substances.

- Thus, I (a thinking thing) can exist without a body.

Proof of the Existence of Material Things

- I have a strong natural inclination to believe external things exist.

- God created me with this inclination.

- If no material things existed, then God would be a deceiver.

- But God is not a deceiver.

- Therefore, material things exist with the properties essential to them.

Structure of Reality (Three Parts)

- God – infinite, perfect.

- Minds – finite, thinking, non-extended substances.

- Material things – finite, extended, non-thinking substances.

Phenomena Considered

- Descartes addresses phantom limbs, dreams, and illusions (e.g., dropsy) as cases where senses mislead.

- Such errors arise not from God’s deception but from the mind–body union and the body’s physical conditions.

✅ In short: Meditation VI affirms both the real distinction between mind and body and the existence of material things. The mind is a thinking, immaterial substance; the body is an extended, divisible one.

Both are sustained by God, and reality is ultimately composed of God, minds, and material things.

Comparative Table — The Two Proofs of God (Meditations III vs. V)

| Aspect | Meditation III: Causal (Idea→Cause) Proof | Meditation V: Ontological Argument |

|---|---|---|

| Core aim | Move from the idea of an infinitely perfect being to that being’s existence via a causal adequacy principle (objective reality of the idea needs a cause with at least that much formal reality). | Show that existence belongs to God’s essence; denying God’s existence would be like denying necessary properties of a triangle—impossible by definition. |

| Key premise (what the idea contains) | “By the name God I understand a substance infinite [eternal, immutable], independent, all-knowing, all-powerful …” | “Existence can no more be separated from the essence of God than the idea of a mountain from that of a valley … or the equality of a triangle’s three angles to two right angles.” |

| Driving principle | Causal adequacy: the objective reality in an idea requires a cause with at least as much formal reality; a finite mind can’t be the adequate cause of the infinite. “It is absolutely necessary to conclude … that God exists.” | Essence–existence inseparability: just as you can’t conceive a triangle lacking its angle-sum, you can’t conceive a supremely perfect being lacking existence. “The existence [of God] is at least as certain as any truth of mathematics.” |

| What it delivers | A first proof anchoring the reality behind the clear and distinct idea of God; sets up why clear and distinct cognition can be trusted (non-deceiving cause). | A second proof showing that from essence alone (no appeal to senses) we get existence—a linchpin of rationalism and clear and distinct certainty. |

| Role in the whole | Certifies the step from cogito to a non-deceiving God; underwrites the general rule: what’s grasped clearly and distinctly is true. | Reinforces the certainty of mathematics and the essences of material things; tightens the bridge from clear and distinct grasp to truth. |

| Classic worry | The “Cartesian circle”: do we rely on clear and distinct ideas to prove God, and on God to guarantee clear and distinct ideas? (For the standard summary, see Britannica.) | |

| Numbers to remember | 1 causal proof here (III) + 1 ontological proof (V) = 2 proofs across 6 meditations (first ed. 1641, second ed. 1642). |

3. Critical analysis

3.1 Evaluation of content

Methodic doubt (Meditation I).

Descartes starts by showing how even robust beliefs can be undermined: sense illusions, dreaming, and finally the evil (or “malicious”) demon hypothesis—imagine a deceiver so powerful that even arithmetic might mislead us. This is not cynicism; it’s stress-testing the edifice of belief to locate bedrock. He famously dramatizes it (paraphrasing): if a powerful deceiver worked constantly to fool me, what would survive?

The Cogito (Meditation II).

Under maximal doubt, one truth survives: I am thinking; therefore, I exist. In Descartes’ words: “‘I am, I exist’ is necessarily true” (every time I conceive it). That certainty is self-verifying: doubting it performs the very act that confirms it.

What the “I” is (res cogitans).

From here, Descartes identifies himself essentially as a thinking thing (understanding, affirming, denying, willing, imagining, sensing), not as a bodily animal. He emphasizes that intellectual apprehension is distinct from imagination and sense.

The famous wax example shows that a piece of wax can change every sensory property (shape, smell, texture) and still be known as the same wax only by the intellect; so the mind knows more certainly than the senses. (He does not deny bodies; he clarifies what provides certainty.)

Clear and distinct perceptions.

The cogito presents a model of certainty. Descartes generalizes: whatever we clearly and distinctly perceive is true. This is not carte blanche for any hunch; “clear” contrasts with obscure and “distinct” with confused (precision matters). SEP’s analysis is still the best overview of how that standard functions and what it excludes.

God and the rebuilding of knowledge.

Descartes offers two routes (trademark and ontological arguments) for God’s existence. The point is not theological grandstanding; it’s to defeat the hypothesis that a deceiver could warp even our mathematical judgments. If God is perfect, God is not a deceiver, so our clear and distinct perceptions are reliable in the long run. (He still warns about human error as a will/intellect mismatch—Meditation IV.)

Material world and mind–body dualism (Meditation VI).

Finally, Descartes argues for the real distinction between mind (thinking, unextended) and body (extended, unthinking), and—importantly—that material things exist. He adds that nature teaches a tight mind-body union (we feel pain as embodied, not as a pilot in a ship). This combination yields dualism plus a strong embodiment insight about sensation and wellbeing.

Does the book support its claims?

- Internal support: The stepwise structure—doubt → cogito → criterion → God → world/body—shows a logical dependency among claims. Even critics who reject parts (e.g., the God proofs) typically accept the cogito and the method’s rigor.

- External probing: The Objections and Replies are an extraordinary built-in peer review, documenting sophisticated criticisms (from Hobbes, Gassendi, Arnauld, etc.) and Descartes’ counter-moves—rare for the 17th century and invaluable for readers today.

Where critics push back (e.g., the Cartesian Circle).

A classic worry: to prove God, Descartes seems to rely on the clear and distinct standard; yet the truth of that standard, he also says, depends on a non-deceiving God. Is that circular?

The scholarly debate is complex (there are nuanced responses about memory, current intuition, and levels of certainty), but it’s the most famous pressure-point in the book and appears in every serious guide, covered by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Bottom line on support:

Even if you bracket the God proofs, the cogito, the mind–body distinction, and the epistemic ideal of clarity/distinctness remain extraordinarily influential and are argued with uncommon care, fulfilling the book’s stated goal: find an unshakeable foundation for knowledge and rebuild from there.

3.2 Style and accessibility

Descartes writes in the first person, with short, lucid paragraphs, turning what could be technical metaphysics into something you can follow line-by-line—like a lab notebook for certainty. The “six days” structure (yesterday/today) gives you a narrative spine: doubt yesterday’s beliefs; examine today’s; repeat.

There’s no fluff; each image (dreams, wax, malicious demon) is carefully chosen to pressure-test a different source of belief. Readers from STEM backgrounds often find the tone unusually clean compared with other classics.

3.3 Themes and contemporary relevance

- Foundationalism & first-person authority: The idea that knowledge starts with what the mind can indubitably grasp remains foundational in epistemology.

- Skepticism & simulation: The evil demon is the ancestor of modern brain-in-a-vat and simulation arguments; it still frames discussions about whether AI-generated realities could fool us.

- Mind–body problem: Descartes gives the classic dualist picture (mind as thinking, unextended; body as extended). Even those who reject dualism use his articulation as the baseline. Britannica’s entry remains a solid neutral overview of the dualism as presented in the Meditations.

- Standards of evidence: “Clear and distinct” remains a powerful ideal—today we might say model transparency, operational definitions, replicability in science. SEP’s treatment traces how that ideal survives and where it breaks.

3.4 Author’s authority

Descartes isn’t just a philosopher; he’s the mathematician who created analytic geometry. That background explains the architectural feel: sweep away weak foundations; rebuild with axiomatic clarity. Academic resources (SEP, Cambridge Companions) routinely present the Meditations as the keystone of the modern turn.

4. Strengths and weaknesses

What I found compelling (strengths)

- Method as experience: Reading the Meditations feels like participating in a mental experiment. Even if you’ve seen the cogito in a meme, actually walking through the doubt sharpens your sense of what counts as evidence.

- Economy: Ideas we spread across entire textbooks—skepticism, foundationalism, theory of ideas, theistic guarantees, mind–body distinction—are all treated in under 100 pages.

- Intellectual honesty: The Objections and Replies format is unusually transparent for its time; Descartes lets critics land real punches, and you watch him respond.

- Staying power: From classroom data to public discourse (BBC explainer videos, general-audience pieces), the text keeps earning attention; it’s a genuine living classic.

What rubbed me the wrong way (weaknesses / fair worries)

- The God hinge: If you’re not persuaded by the God proofs, parts of the architecture (especially the move from the cogito to a guarantee on mathematics and the external world) feel more fragile. The Cartesian Circle worry doesn’t vanish easily.

- Dualism tensions: Descartes is more subtle than the caricature (he talks about mind–body union and embodiment), but the interaction issue—how an unextended mind moves an extended body—remains a friction point for scientifically minded readers.

- Translation variability: Small wording differences (“malicious demon,” “evil genius”) can color how forceful certain passages feel. That’s not a problem unique to Descartes, but it’s noticeable when you cross-read translations.

5. Reception, criticism, influence

Immediate reception: The appended Objections and Replies show how seriously peers engaged Descartes. Hobbes challenged the structure of the arguments; Arnauld pressed the circularity; Gassendi pushed empirical angles. This back-and-forth is effectively an early modern seminar transcript.

Long-term influence:

- “Father of modern philosophy” isn’t empty praise; the reorientation toward epistemic foundations and subjectivity shaped everything from Locke/Hume debates to Kant and beyond. SEP and Cambridge summaries emphasize how the Meditations inaugurates enduring themes.

- Best-of lists & pedagogy: Canon lists and syllabi analyses consistently include the Meditations, reflecting its recommended status for both general and specialist readers. (Guardian’s “100 greatest non-fiction books” includes it; syllabus data shows it perennially assigned.)

- Public thought & media: From BBC-style explainers of the cogito to countless introductions across universities, the text is still how we teach certainty. According to BBC-associated programming, the idea remains a cultural touchstone.

Why it’s one of the best and most recommended philosophy books of all time:

Because it does something few books do: it shows you how to tear down belief to one indestructible truth and rebuild carefully—while inviting critics into the same volume to fight with it.

It’s short, method-driven, and globally teachable. Cambridge calls it “one of the most widely studied” texts; syllabus and canon data back that up.

6. Quotations

“‘I am, I exist’ is necessarily true.”

(Paraphrase for context) Descartes invites us to imagine a malicious demon bent on deceiving us about everything—even mathematics—to pressure-test what can survive doubt.

(Paraphrase for context) The wax teaches that what we know is grasped by the intellect, not secured by changing sensory features.

(Paraphrase for context) Whatever is clearly and distinctly perceived is true; God, being perfect, is no deceiver, restoring mathematical certainty.

7. Comparison with similar works

- Augustine’s Confessions / City of God (si fallor, sum) vs Descartes’ cogito: Augustine offers a theological context and a precursor to self-certainty; Descartes systematizes it as a methodological foundation for modern knowledge.

- Montaigne’s Essays vs Descartes’ method: Montaigne embraces skepticism to cultivate modesty and self-knowledge; Descartes uses skepticism as a tool to defeat skepticism.

- Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason vs Descartes’ clarity/distinctness: Kant keeps the apodictic feel of rational certainty but relocates it to the conditions of possible experience, altering the project after Descartes’ dualism.

- Hume’s empiricism vs Descartes’ rationalism: Hume doubts that rational insight alone secures facts about the world; he privileges experience and habit over ideas to establish knowledge. (Reading the Meditations first makes Hume’s critique far clearer.)

8. Conclusion (recommendation)

Overall impression: Meditations on First Philosophy is short, surgical, and still startling. The methodic doubt cuts through noise; the cogito is a razor-sharp anchor; the clear and distinct ideal is a timeless standard for intellectual hygiene.

Weaknesses—especially the God hinge and dualism—are not dealbreakers; they’re educational. Watching the Objections/Replies is like an early modern peer-review drama that teaches you how philosophy improves by being challenged.

Who should read it?

- Students in philosophy, psychology, AI, cognitive science (to learn how to argue from first principles).

- Researchers & engineers who want a mental model for foundations and verification.

- General readers willing to slow down for a few evenings and think carefully.

General vs specialist: The book is short and lucid—excellent for general audiences with patience; it’s also the specialist’s perpetual starting point, because every later debate (knowledge, perception, selfhood, God, science) talks to Descartes. Highly recommended—and rightly one of the world’s most assigned and most recommended philosophy books.

9. FAQ — Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy

1) What is the “Cartesian Circle”?

Short answer: It’s the alleged circularity that Descartes uses clear and distinct ideas to prove God, while also relying on God (as non-deceiver) to guarantee the truth of clear and distinct ideas. Arnauld flagged this loop in the Objections and Replies.

Why it matters: If the circle held, the certification of mathematics and metaphysics would wobble. Descartes’ reply is that the presented clarity of a cognition is self-evident; God’s role is to secure its stability when we’re no longer attending. See Descartes’ own linkage of certainty to God’s non-deception and the persistence of knowledge after attention wanes.

2) Is the cogito a syllogism?

Short answer: No. It’s not “All thinkers exist; I think; therefore I exist.” It’s a self-verifying act: while thinking (even doubting), existence is indubitable. Descartes’ own formulation: “I am, I exist must be true whenever I state it or mentally consider it.”

Context: The cogito arises even under the evil demon hypothesis; deception presupposes a subject to be deceived.

3) Why is mind–body dualism controversial?

Short answer: Descartes argues for a real distinction: mind is an unextended, indivisible thinking substance; body is extended and divisible. The inference: what we can clearly and distinctly conceive apart can exist apart. (His divisibility remark: “we are not able to conceive the half of a mind.”)

Controversy: Critics press the interaction problem (“How do unextended thoughts move extended bodies?”) and worry about explaining sensations that seem to be world-bound. Even sympathetic summaries treat dualism as the source of the modern mind–body problem.

His closure: He also argues for a robust union of mind and body and for the existence of material things (via natural inclination + God’s non-deception).

4) What does “clear and distinct” really mean?

Short answer: It’s Descartes’ truth-test: “all that is very clearly and distinctly apprehended (conceived) is true.” He makes it a general rule after the cogito.

Security: Because God exists and is no deceiver, what we once grasped clearly remains true even when we’re not actively rehearsing the proof.

5) What is the evil demon (or “malicious deceiver”) hypothesis?

Short answer: A methodological device to push doubt to the limit—even arithmetic might be suspect if a supremely cunning deceiver manipulated our faculties. It’s how Descartes stress-tests certainty and arrives at the cogito. (Key summary + excerpt.)

Function: It motivates the need for a guarantor (a non-deceiving God) to underwrite knowledge that’s clear and distinct.

6) What’s the ontological argument (Meditation V), in one breath?

Short answer: From the essence of a supremely perfect being to existence: you can’t conceive God without existence, just as you can’t conceive a mountain without a valley. Therefore, God exists.

Descartes’ emphasis: Existence belongs to God’s essence; this certainty is “as certain” as mathematics. (See also his triangle analogy and remarks that existence “pertains” to God’s essence.)

7) What are innate, adventitious, and factitious ideas—and why do they matter?

Short answer: Innate ideas are “in us” (e.g., God, mind, extension); adventitious come from experience; factitious are invented. Descartes argues the idea of God can’t be caused by a finite mind; it has “infinite objective reality,” so its cause must have at least as much formal reality—namely, God.

Payoff: This is the causal proof of God in Meditation III and the backbone of his move beyond solipsism.

8) How does the wax argument support the priority of the mind over the senses?

Short answer: The same wax persists through changes of color, shape, and texture; what tracks identity is not sensation but intellect—we know the wax “by the intellect alone.” Therefore, we know the mind (as thinker) more certainly than bodies.

9) How does Descartes justify the existence of material things?

Short answer: Two strands:

- Natural inclination + God’s veracity: It would make God a deceiver if the powerful inclination to believe in an external world were false; so material things exist.

- Imagination faculty: Imagination operates as a “turning toward” something extended, suggesting a bodily correlate.

10) What exactly are “objective reality” and “formal reality” of ideas?

Short answer: Objective reality = the representational content of an idea (its aboutness); formal reality = actual reality of the cause. The causal adequacy principle: the cause must contain at least as much formal reality as the idea has objective reality. Descartes uses this to argue from the idea of God (infinite objective reality) to God’s existence (infinite formal reality).

11) Does Descartes think mathematics is invented or discovered?

Short answer: Discovered. He treats mathematical essences (e.g., triangle’s angle sum) as immutable and eternal—“not framed by me.” That bridges the essence of material things with the certainty of clear and distinct cognition.

12) What practical rule should I follow to avoid error?

Short answer: Let understanding lead and the will follow. Suspend assent until the content is clear and distinct—“If I suspend judgement when I don’t clearly and distinctly grasp what is true, I obviously do right.” Misuse of freedom (will outrunning intellect) is error.

Quick figures to remember

- 6 meditations (first ed. 1641, second ed. 1642).

- 2 proofs of God: causal (III) + ontological (V).

- 1 master rule: what’s clear and distinct is true.

Footnotes

- In Meditation I, Descartes introduces two powerful skeptical devices: the Dream Argument and the Evil Demon Hypothesis. Both are designed to push doubt to its extreme and test the reliability of our beliefs.

The Dream Argument

Descartes notices that there are times when he has dreamt of sitting by the fire, writing a paper, or speaking with friends, and in those moments he was wholly convinced of the reality of those experiences. From this he concludes that there are no sure signs to distinguish waking from dreaming.

As he puts it, “he is often convinced when he is dreaming that he is sensing real objects” and reflects that “often he has dreamed this very sort of thing and been wholly convinced by it”.

Even if dreams draw their imagery from waking life (like a painter combining elements of real things to create imaginary creatures), this still undermines certainty: it shows that sense-based beliefs—about sitting by the fire, seeing colors, or hearing sounds—can be false.

The Dream Argument suggests at least the possibility that at any given moment we might be dreaming, which means sensory experience is not a secure foundation for knowledge.

The Evil Demon Hypothesis

To radicalize doubt even further, Descartes imagines a deceiver more powerful than dreams: not God (who is perfectly good), but “some malignant demon, who is at once exceedingly potent and deceitful, has employed all his artifice to deceive me”. Under this hypothesis, the demon could manipulate even the simplest truths, like mathematics—so that “2 + 3 = 5” might be false if the deceiver wills it.

The point is not that such a demon exists, but that imagining it allows Descartes to doubt everything that could be doubted, including mathematics and logic, not just sensory perception. The demon hypothesis brings him to a position where he can suspend judgment entirely, guarding against falsehoods until he discovers something indubitable.

Distinction Between the Two

Dream Argument: undermines trust in the senses by showing that we cannot reliably tell waking from dreaming.

Evil Demon Hypothesis: undermines trust in all cognitive faculties (senses, memory, even reasoning), suggesting a universal deception.

As one commentator notes, the Dream Argument “suggests only that the senses are not always and wholly reliable,” while the Evil Demon Argument “does away with [them] altogether”.

In brief: The Dream Argument shows that sensory experience cannot give absolute certainty. The Evil Demon Hypothesis pushes doubt further, questioning even logic and arithmetic. Together, they clear the ground for Descartes’ famous discovery in Meditation II: that even in the face of such doubts, the cogito—“I think, I exist”—remains indubitable. ↩︎ - Descartes’ methodic doubt (sometimes called “methodological doubt”) is the central strategy of Meditations on First Philosophy. It is not a random skepticism but a deliberate procedure to identify beliefs that can be held with certainty.

What it is

Methodic doubt means systematically rejecting as false any belief that can be doubted, even slightly, until only indubitable truths remain. As Britannica summarizes: it is a “systematic procedure of rejecting as though false all types of belief in which one has ever been, or could ever be, deceived”.

How it works in the text

In Meditation I, Descartes explains that he must “once in his life rid himself of all the opinions” he had adopted and start anew from secure foundations. Rather than test every belief one by one, he reasons that if he finds grounds for doubt in their foundations, the whole structure falls.

He then applies three escalating skeptical arguments:

Sensory deception: Senses sometimes mislead (e.g., a distant tower looks round when it is square), so they cannot be completely trusted.

Dream argument: We can never be sure we are not dreaming, so sensory-based beliefs are always open to doubt.

Evil demon hypothesis: Even mathematics could be false if a powerful deceiver manipulated our reasoning.

Its purpose

Descartes emphasizes that this universal doubt, though uncomfortable, is useful:

It “delivers us from all prejudice” and frees the mind from the senses. It ensures that “it is impossible for us to doubt wherever we afterwards discover truth”.

What it achieves

Methodic doubt leads directly to the cogito in Meditation II: even if I doubt everything, the very act of doubting proves that I exist as a thinking being. Later meditations rebuild knowledge—God’s existence, the rule of clear and distinct perception, the essence of material things, and the mind–body distinction—on this foundation. ↩︎