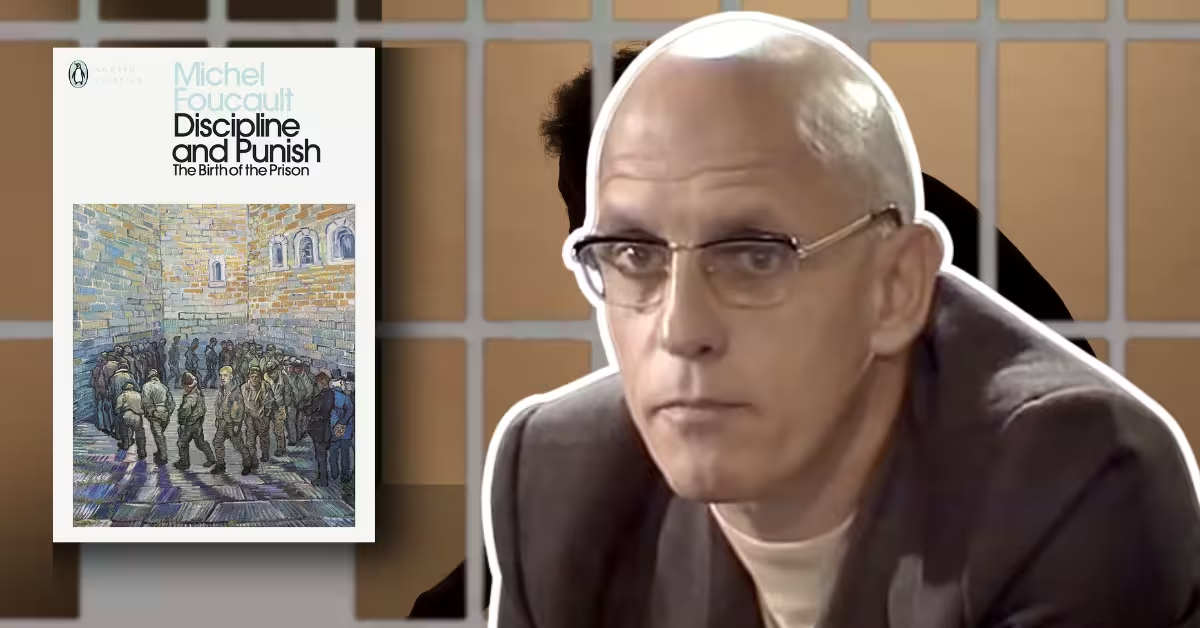

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison is a seminal work by Michel Foucault, one of the most influential philosophers and historians of the 20th century. Originally published in French in 1975 as Surveiller et punir, it was later translated into English by Alan Sheridan and released in the U.S. in 1977 by Pantheon Books.

Foucault, a professor at the Collège de France and an intellectual giant within postmodern and post-structural thought, held significant academic and cultural sway in the mid-to-late 20th century. He was known for his deep dives into the relationship between knowledge, power, and social institutions. Discipline and Punish belongs to a genre blending historical sociology, philosophy, and criminology, effectively dismantling the evolution of modern disciplinary mechanisms within Western society.

The core thesis of Discipline and Punish is chillingly clear: modern systems of punishment have shifted from the body to the soul, not out of humanism, but to exert more efficient control. Foucault argues that punishment moved from public torture to hidden incarceration not because of moral progress, but due to the rise of disciplinary power, which is more pervasive, invisible, and internalized.

In his own words:

“The body as the major target of penal repression disappeared. The body now serves as an instrument or intermediary: if one intervenes upon it… it is in order to deprive the individual of a liberty that is regarded both as a right and as property.“

Table of Contents

Background

Before diving into the prison, Foucault situates punishment in a long genealogy, moving from monarchical sovereignty, where the king’s power was expressed in spectacular public executions, to disciplinary society, where power is diffuse, systemic, and internalized. The historical background he traces spans from 18th-century Europe’s criminal justice reform to the development of surveillance-based institutions like schools, hospitals, and military barracks.

This transition reflects a deeper philosophical argument: modernity has not erased oppression—it has refined and concealed it. With the abolition of torture came rationalized, scientific methods of control, embedded in everyday life. For Foucault, this transformation doesn’t signify progress but rather a new regime of “docility” and submission.

Summary

Foucault divides Discipline and Punish into four parts, each structured thematically:

Part I: Torture

Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison begins with a searing juxtaposition: the graphic 1757 execution of Damiens, a regicide, against the regimented, minute-by-minute schedule of a 19th-century prison for young offenders. This striking contrast is not merely historical curiosity. Rather, it is emblematic of a profound shift in the logic and structure of punishment—one that transitioned from the theatrical and violent targeting of the body to a regulated, bureaucratic disciplining of the soul. Part I, titled Torture, introduces this transformation and sets the philosophical stage for what Foucault calls the “birth of the prison.”

From Scaffold to Schedule: A Paradigm Shift

Foucault opens with the execution of Robert-François Damiens, whose public torture was not only state-sanctioned but ritualized. This “ceremonial of punishment” reveals a justice system grounded in visibility, brutality, and divine authority. Foucault writes:

“The body of the condemned man was the place where the vengeance of the sovereign was applied, the anchoring point for a manifestation of power” (Foucault, p. 34).

Public torture was more than just retribution—it was a theatre of power. The sovereign’s body had been violated, and only by desecrating the criminal’s could power be reaffirmed. The execution was thus a political spectacle, designed to instill fear and awe in the masses. The king’s justice was seen, heard, and felt in the tearing of flesh, the cries of agony, and the community of spectators.

However, by the early 19th century, this vivid pageantry gave way to regulated time-tables and architectural confinement. In 1837, chain-gangs in France were replaced by black-painted prison carts. The executioner was replaced by bureaucrats, chaplains, and wardens. Where once the scaffold stood central in the town square, justice now receded into the silent corridors of prisons.

This shift, according to Foucault, is not merely a humanistic reform—as it is often portrayed—but a change in the technology of power. In other words, modern punishment does not abandon power; it relocates and refines it.

Supplice and the Body: The Ritual of Power

A crucial term in Part I is “supplice,” inadequately translated as “torture.” It encapsulates the elaborate ritual of physical suffering designed not only to punish but to demonstrate power. The executioner was not merely an agent of justice but a performer in a sacred drama. Foucault explains:

“The public execution is now seen as a hearth in which violence bursts again into flame” (p. 9).

Yet this ritual of power held dangers. Spectators could begin to identify with the condemned rather than the sovereign. The scaffold could invert roles, turning executioners into murderers and criminals into martyrs. Foucault cites Beccaria, who critiqued such executions for reenacting the very violence they condemned:

“The murder that is depicted as a horrible crime is repeated in cold blood, remorselessly” (p. 10).

In response, modern justice retreats from the public eye. Punishment becomes hidden, abstracted, and internalized. This is a strategic withdrawal. As Foucault notes:

“It is the certainty of being punished and not the horrifying spectacle of public punishment that must discourage crime” (p. 11).

The Soul Takes Center Stage

As the state’s grip on the physical body lessened, its reach into the soul expanded. The spectacle was replaced with introspection; the torment of the flesh, with correction of the self. A crucial line from Mably illustrates this transformation:

“Punishment, if I may so put it, should strike the soul rather than the body” (p. 16).

The criminal was no longer merely a lawbreaker to be physically broken, but a subject to be known, classified, and ultimately reformed. Foucault reveals the emergence of new disciplines—psychiatry, pedagogy, medicine—that intervened in justice, constructing a knowledge of the criminal:

“The criminal’s soul is not referred to in the trial merely to explain his crime… it too, as well as the crime itself, is to be judged and to share in the punishment” (p. 19).

This redirection is not, as Foucault warns, a softer justice. Instead, it is more insidious—more total. The body may no longer be whipped, but the soul is now examined, diagnosed, and shaped. The apparatus of judgment multiplies: experts, psychologists, educationalists—all become agents of the penal process.

Technologies of Control

This new economy of punishment heralds the birth of what Foucault calls “technologies of control.” The prison becomes a laboratory where the individual is observed, classified, and normalized. One notable transformation is in the structure of punishment itself. Public dismemberments are replaced by solitary confinement; shame by introspection; the gallows by the timetable.

Even death—the most final of penalties—is stripped of spectacle. The guillotine, adopted in 1792, enforces equality in death: quick, bloodless, and anonymous. One is reminded of the chilling efficiency Foucault describes:

“The guillotine takes life almost without touching the body… It is intended to apply the law not so much to a real body capable of feeling pain as to a juridical subject” (p. 13).

This is not progress in a moral sense; it is optimization. Modern punishment becomes about regulation, not revenge; management, not morality.

The Persistence of the Body

Despite this ostensible retreat from corporeality, Foucault argues that the body never fully disappears from punishment. Imprisonment, though touted as humane, carries its own bodily degradations: hunger, isolation, sleep deprivation, surveillance. The prison, with its panopticonic gaze, may not tear flesh, but it fragments subjectivity.

Foucault notes this residual torture:

“Imprisonment has always involved a certain degree of physical pain… It is difficult to dissociate punishment from additional physical pain. What would a non-corporal punishment be?” (p. 20)

Thus, modern punishment cloaks its violence in the language of care. Doctors monitor executions, tranquilizers precede death sentences, and psychological reports determine sentencing lengths. It is in this veneer of benevolence that modern power hides its greatest mastery.

A New Politics of the Body

Part I of Discipline and Punish thus lays the groundwork for Foucault’s larger thesis: modern society does not relinquish power over the body; it merely recalibrates it. The sovereign’s spectacular violence gives way to the diffuse control of institutions. The criminal becomes a subject—not of divine vengeance—but of psychological scrutiny and bureaucratic normalization.

What emerges is not a more just system, but a more effective one. A system that, rather than punishing crimes, manages risks; that, rather than disciplining acts, disciplines desires.

Foucault’s challenge to the reader is not to see this shift as progress but as transformation. What we call reform, he warns, may be nothing more than the fine-tuning of domination.

Part II: Punishment

In Part II of Discipline and Punish , titled Punishment, Michel Foucault maps the reconfiguration of punitive power from the 18th century onwards.

Following the grimly theatrical punishments of the Ancien Régime, the state transitions to a more restrained but insidiously pervasive penal regime. The spectacle disappears, but punishment does not. It becomes rationalized, internalized, and diffused through new institutions and epistemologies. Foucault’s central claim is unmistakable: the goal of modern punishment is not merely retribution, but the construction and normalization of obedient subjects.

This section unfolds in two major chapters: “Generalized Punishment” and “The Gentle Way in Punishment.” Together, they demonstrate how sovereignty gave way to legality, how the body yielded to the soul, and how justice became increasingly an apparatus of surveillance, classification, and control.

1. From Sovereignty to Legality: Redefining the Right to Punish

Foucault begins by situating the transformation of punishment within a political context: the decline of sovereign power and the rise of representative democracy and bourgeois legalism. The king’s body once stood as both symbol and instrument of justice. But with the Enlightenment came a demand for legality, transparency, and universality. The law was no longer divine; it was social. The power to punish had to be redistributed accordingly.

As Foucault notes:

“The power to punish… must be founded not on the right of the sovereign to punish, but on the need to defend society against the criminal” (p. 73).

The law began to present itself as a rational mechanism, a social contract aimed at protecting collective interests. Crimes were no longer violations against the sovereign’s body, but transgressions against a shared social code. This shift justified a new kind of punishment—less about pain, more about correction.

But Foucault warns: this was not a humanitarian awakening. Instead, it was a political realignment. The bourgeois class, emerging as the new hegemon in 18th-century Europe, required a stable legal system to protect property and manage social unrest. The penal system evolved accordingly.

2. Generalized Punishment and the Extension of Control

Rather than becoming more humane, punishment became more generalized. Foucault argues that instead of disappearing, punitive power now infiltrates all sectors of life. He writes:

“Punishment had to be channelled through a whole series of subsidiary authorities… These disperse mechanisms of punishment functioned beneath the visible forms of justice” (p. 80).

A constellation of institutions—schools, factories, hospitals, military barracks—began to replicate the structures of penal control. They produced “docile bodies,” disciplined and habituated to authority. What had once been spectacular and episodic became mundane and continuous.

In this “carceral continuum,” punishment is no longer restricted to the courtroom or the scaffold. It becomes a daily mechanism of observation, evaluation, and regulation. The power to punish is exercised by teachers, doctors, factory supervisors, and social workers. The result is a disciplinary society where everyone is both the object and subject of surveillance.

“Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?” (p. 228)

This famous line encapsulates Foucault’s argument: punishment is no longer exceptional. It is systemic. It is structural. It is everywhere.

3. The “Gentle” Way: Rationalizing Pain

The second chapter in Part II, “The Gentle Way in Punishment,” interrogates the ideology of penal reformers who argued for milder, more “enlightened” forms of punishment. Thinkers like Beccaria and Bentham are often seen as moral pioneers, but Foucault reveals a more complex dynamic.

The move from scaffold to cell was not just about kindness. It was about efficiency, predictability, and control. Public torture was unpredictable: it could incite sympathy, provoke riots, and fail to produce desired confessions. It depended on spectacle. Reformers sought something more scientific.

Foucault explains:

“The reformers wanted to allocate punishment in a manner that was calculable, inevitable, and capable of producing useful effects” (p. 88).

Thus, punishment had to be:

- Quantified (clear sentences),

- Internalized (through guilt and self-monitoring),

- Rehabilitative (aligned with economic productivity).

This was not an abandonment of punitive power but its rationalization. The penal system became a site of knowledge-production: it classified criminals, predicted recidivism, and administered rehabilitation programs. Punishment became a scientific domain.

4. The Birth of Criminal “Character”

Another major development in this period was the invention of the criminal subject. In older systems, it was enough to punish an act. But the modern penal system began to concern itself with the actor. Who is the criminal? What are his motivations, pathology, background?

Foucault notes:

“It is no longer simply the offence, but also the offender that is judged” (p. 91).

This shift introduced new professions into the penal sphere: psychiatrists, criminologists, psychologists, and social workers. These figures provided the knowledge necessary for personalized punishment. The law now asked not just “What was done?” but “Who did it?” and “What can be done to change him?”

As a result, punishment became indeterminate and extensible. Sentences could be extended if reform was not achieved. Parole became contingent on behavior. The line between treatment and punishment blurred.

This represents a fundamental change in the nature of justice. Punishment no longer ends with the sentence. It begins a “correctional career”—a continuous process of assessment, rehabilitation, and surveillance.

5. Punishment as Political Technology

At the heart of Part II is Foucault’s claim that punishment is a political technology. It is not simply a legal tool, but a method by which society shapes and organizes itself. The penal system is one node in a vast network of disciplinary mechanisms.

This political function is evident in the ways punishment reproduces class relations. The crimes most often punished—theft, violence, disorder—are those associated with the working class. Meanwhile, bourgeois crimes—financial fraud, political corruption—are treated more leniently or invisibly.

Foucault writes:

“The prison functions as a filtering, concentrating mechanism: a mechanism that converts illegalities into delinquencies and distributes them hierarchically” (p. 112).

Thus, the penal system is not simply reactive; it is productive. It produces the category of the “delinquent”—a figure who can be watched, studied, corrected, and reinserted into the system. In this way, punishment becomes a means of population management.

6. The Illusion of Reform

Despite appearances, reform has not diminished punishment—it has refined it. The reformist agenda of the 18th and 19th centuries cloaked a deeper expansion of punitive power. By cloaking itself in the language of science, morality, and care, the state made punishment more total, more hidden, and more effective.

Foucault’s tone is skeptical of liberal narratives of progress:

“One should not be surprised that the prison resembles the factory, the school, the barracks. These institutions reproduce the carceral continuum of modern society” (p. 228).

What modernity achieved was not mercy, but optimization. The “gentle way” did not abolish cruelty—it relocated it. Instead of being inflicted on the body in public, it is inflicted on the soul in private. Instead of visible scars, it leaves internal marks—of shame, of guilt, of normalization.

A New Logic of Punishment

Part II of Discipline and Punish reveals a radical transformation in the mechanisms and rationalities of punishment. The sovereign’s sword has been replaced by the administrator’s file, the psychologist’s chart, and the warden’s report. The body has been spared, only for the soul to be colonized.

This is not a story of progress, but of mutation. The modern penal system does not abolish power—it perfects it. It replaces direct violence with surveillance, and public spectacle with quiet coercion. As such, punishment becomes not an endpoint, but a process—one that continues long after the crime is forgotten.

Foucault leaves us with a haunting insight: modern punishment is not less violent; it is simply more precise.

Part III: Discipline

If Torture unveils the sovereign’s brutal power over the condemned body, and Punishment explains the transition to a more veiled, bureaucratic form of justice, then Part III of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish , titled Discipline, is the most philosophically expansive. It develops the theoretical heart of Discipline and Punish. Here, Foucault introduces one of his most influential ideas: the concept of disciplinary power, which creates “docile bodies”—human beings conditioned to be productive, compliant, and self-regulating.

Foucault’s key argument is that the emergence of modern institutions (prisons, schools, factories, hospitals, military barracks) is inseparable from the rise of disciplinary technologies designed to manage bodies, gestures, movements, and even time itself. Discipline is not merely about punishment; it is a technique of power that operates silently, efficiently, and pervasively. It is not just repressive but productive—it produces identity, knowledge, and subjectivity.

This section is divided into three chapters: “Docile Bodies,” “The Means of Correct Training,” and “Panopticism.” Together, they reveal how modern power no longer strikes the body in theatrical fashion, but enters the body through routines, spaces, and gazes that shape how individuals live and think.

1. The Body as Target: Producing Docility

Foucault opens the chapter Docile Bodies with a fundamental premise: the body is not a neutral, biological object, but a political and economic one. The aim of disciplinary power is to make the body “docile”—that is, easily manipulated, trained, and optimized for work, warfare, and learning.

He writes:

“Discipline produces subjected and practiced bodies, ‘docile’ bodies. Discipline increases the forces of the body (in economic terms of utility) and diminishes these same forces (in political terms of obedience)” (p. 138).

This dual movement—maximizing utility while minimizing resistance—is the essence of discipline. It is a power that does not destroy, but shapes. Unlike sovereign power, which displays strength through brutality, disciplinary power functions quietly, at the level of micro-relations.

Three major techniques underpin this disciplinary economy:

a) The Art of Distributions

Discipline begins by organizing space. It divides and assigns bodies to specific places: the school desk, the hospital bed, the prison cell. This spatial ordering, called “partitioning,” is not just architectural; it encodes hierarchies and surveillance. For example, students are separated in rows for easier observation. Foucault notes:

“Disciplinary space tends to be divided into as many sections as there are bodies or elements to be distributed. One must eliminate the effects of imprecise distributions, the uncontrolled disappearance of individuals, their diffuse circulation, their unusable and dangerous coagulation” (p. 143).

Space becomes a grid in which individuals are classified, made visible, and measurable.

b) The Control of Activity

Discipline manipulates time. Every gesture is scheduled, repeated, and assessed. Time-tables structure daily life: rise, pray, work, eat, sleep. This “temporal discipline” produces habits, and through habit, obedience. As Foucault notes:

“Discipline organizes an analytical space-time; it assures the elaboration of a meticulous control of operations, a detailed control of the body and its movements” (p. 149).

What looks like a simple routine is in fact a mechanism of power.

c) The Organization of Geneses

Discipline shapes development. It sequences training over time, with a beginning, middle, and end. Think of the military drill or classroom instruction: each stage prepares for the next, and failure to conform at any stage reflects personal inadequacy. Progress is thus both regulated and moralized.

d) The Composition of Forces

Lastly, discipline combines individuals into collective units—armies, classes, factories—while still differentiating their roles. The goal is not simply mass coordination, but the strategic multiplication of forces. Foucault states:

“The carefully measured combination of individual bodily movements turns into collective force” (p. 164).

Discipline, in this way, is both atomizing and collectivizing: it isolates individuals while making them function within systems.

2. Techniques of Training: Observation, Judgment, and Examination

The next chapter, The Means of Correct Training, outlines the specific instruments through which discipline is imposed. These are not acts of violence, but rituals of surveillance and assessment.

a) Hierarchical Observation

Disciplinary power depends on the ability to observe. The observer—teacher, warden, supervisor—does not need to act to exert control. The mere fact of being watched induces conformity. Foucault notes:

“Disciplinary power is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on those whom it subjects a principle of compulsory visibility” (p. 187).

This asymmetry of vision—being seen without seeing—internalizes power within the subject.

b) Normalizing Judgment

The second technique is judgment against a norm. Individuals are measured not simply by what they do, but by how closely they approximate an ideal. This concept of “the norm” replaces the old binary of lawful/unlawful with a continuous spectrum of evaluation. As Foucault writes:

“The perpetual penalty that traverses all points and supervises every instant… compares, differentiates, hierarchizes, homogenizes, excludes. In short, it normalizes” (p. 183).

Grading, ranking, and performance reviews are all manifestations of this logic.

c) The Examination

The examination unites observation and judgment. It is a ritual that produces knowledge and power simultaneously. Through the exam, individuals are rendered as cases—objects of study, measurement, correction. This knowledge is archived, forming dossiers and records that follow the individual through life.

“The examination is at the center of the procedures that constitute the individual as effect and object of power and knowledge” (p. 192).

This is perhaps the most important insight in this section: disciplinary power is epistemological. It does not just dominate—it produces truth about the subject. The individual becomes both the object of knowledge and the subject of subjection.

3. Panopticism: The Architecture of Power

In Panopticism, Foucault introduces the most iconic image in Discipline and Punish: Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a circular prison where inmates are constantly visible to an unseen observer. For Foucault, the Panopticon is not just a building—it is a metaphor for modern power.

“The Panopticon is a machine for dissociating the see/being seen dyad: in the peripheric ring, one is totally seen, without ever seeing; in the central tower, one sees everything without ever being seen” (p. 201).

The genius of the Panopticon lies in its internalization of surveillance. Prisoners modify their behavior as if they are always being watched. The result is voluntary obedience, not through fear of punishment, but fear of visibility.

This principle extends beyond prisons. Schools, factories, hospitals—all adopt the panoptic logic. Foucault writes:

“A generalized model of functioning: a way of defining power relations in terms of the everyday life of men” (p. 205).

The Panopticon becomes a political technology—a model for managing populations through continuous, impersonal observation.

4. From Discipline to Disciplinary Society

What emerges in Part III is the thesis that discipline is the dominant technology of modern power. It is not a side effect of reform, but the very condition of modern governance.

“Discipline ‘makes’ individuals; it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise” (p. 170).

We are not simply governed by laws or economic interests, but by regimes of normalization—invisible systems that mold our bodies, behaviors, and beliefs. Through discipline, power becomes diffuse, continuous, and productive.

Foucault ends this section by reminding us that these technologies are not inherently evil or benevolent. They are efficient. They serve political and economic needs, often invisibly. The danger lies not in punishment per se, but in how we do not notice that we are being shaped.

Part III of Discipline and Punish is one of the most influential texts in 20th-century philosophy. It offers a new framework for understanding power—not as a top-down force, but as a network of micro-relations embedded in everyday institutions. Power is not just repressive; it is constitutive. It creates categories, identities, and norms.

Discipline, then, is the grammar of modern life. It teaches us how to sit, speak, work, and think. It is a power we feel not as force, but as structure. And in that quiet efficiency, it may be more absolute than any sovereign’s sword.

“Discipline ‘makes’ individuals; it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise.“

The infamous Panopticon—a circular prison designed by Jeremy Bentham where inmates can always be seen but never know when they are being watched—serves as the metaphor for modern surveillance. Foucault extends this idea to schools, factories, hospitals, and beyond.

Part IV: Prison

In the final section of Discipline and Punish , Michel Foucault completes his genealogical journey through Western penal systems by uncovering the logic of the modern prison. Part IV, titled simply Prison, is not a conclusion in the traditional sense, but a culmination—a synthesis of the preceding chapters on torture, punishment, and discipline. It shows how the prison institutionalizes disciplinary power and how it becomes the linchpin of what Foucault calls the carceral system, a dispersed, pervasive network of control.

Foucault’s central thesis is both historical and political: the prison is not merely a response to crime, nor a neutral solution to the problems of justice. It is, instead, a product and producer of the very conditions it claims to combat. Rather than correcting or rehabilitating criminals, prisons serve to manage, observe, and reproduce deviance.

They do so by integrating multiple disciplines—law, medicine, psychology, and education—into a coordinated apparatus of surveillance and normalization.

1. The “Complete and Austere Institutions”: The Rise of the Carceral

Foucault opens this section by examining the genealogy of penitentiary institutions. He discusses the prison-colony of Mettray, established in 1840, as a paradigmatic example of disciplinary enclosure. Mettray was not just a prison—it included a school, a chapel, a workshop, and agricultural labor units. It epitomized the fusion of carceral and corrective ambitions.

Foucault writes:

“It was the most famous example of what was then called a ‘prison without walls,’ a kind of semi-open institution whose aim was not only to punish, but to form, reform, and transform” (p. 265).

Mettray marks the point at which disciplinary technologies converge: surveillance, normalization, and labor. The prison becomes a “total institution,” in Erving Goffman’s sense—a place where every aspect of life is controlled and regimented.

Here, Foucault offers a key insight: the modern prison does not isolate criminality—it produces it. Through classification, repetition, and stigmatization, the prison system constructs the identity of the “delinquent.” This identity is then studied, categorized, and managed.

2. The Delinquent: Birth of a New Subject

Central to Foucault’s argument is the idea that delinquency is not a natural category. It is a constructed subjectivity—one produced by the intersection of legal, psychological, and administrative discourses.

He writes:

“Delinquency… appears as a natural phenomenon, but it is in fact the effect of a tactical construction—an object of knowledge and a target of power” (p. 277).

Unlike the criminal, who merely violates the law, the delinquent is pathologized—diagnosed, treated, and observed. The discourse around delinquency integrates the judiciary with psychiatry, pedagogy, and social work. Thus, the prison no longer punishes acts—it manages individuals.

This fusion of power and knowledge is a continuation of themes developed in Part III: the examination, the dossier, the archive. But in the prison, these become institutionalized and perpetual. Foucault explains:

“The perpetual surveillance of the convict produces knowledge; and this knowledge justifies and perpetuates the surveillance. The prison is both the object and the source of criminological knowledge” (p. 281).

This recursive logic creates a self-fulfilling system. The more the prison observes, the more it “knows”; the more it knows, the more justified it feels in continuing to observe. The delinquent becomes not only an object of punishment but a career path—an identity reinforced by repetition.

3. The Prison as Normative Apparatus

One of Foucault’s most biting critiques is aimed at the ideology of reform. From its inception, the prison was justified as a humane alternative to corporal punishment. It was supposed to be rational, corrective, and tailored to the individual.

Yet as Foucault shows, reform has always been part of the prison’s mechanism of power—not a response to its failure, but a strategy of its success:

“The prison has always been a double operation: to punish and to transform… but this transformation is not towards freedom, it is towards normalization” (p. 232).

Indeed, the prison rarely achieves its purported goal of rehabilitation. Recidivism rates remain high, and former prisoners often face institutional and economic marginalization. However, this failure is itself productive: it justifies further surveillance, additional programs, and new scientific studies. The prison becomes an engine of continuity, not closure.

Foucault adds:

“The prison does not disappear despite its repeated failures. On the contrary, it is this failure that gives it legitimacy. Every reform opens a new space for control” (p. 241).

4. The Carceral Continuum

Perhaps the most expansive and haunting idea in Part IV is the carceral archipelago—a metaphor for how prisons are not isolated institutions but part of a “carceral continuum.”

Foucault writes:

“The carceral is not a perimeter that closes off and excludes; it is a distribution of surveillance techniques that run through the social body” (p. 303).

This carceral logic extends to:

- Schools, with their standardized testing, seating charts, and behavioral assessments;

- Hospitals, where patients are observed and documented under medical gaze;

- Military institutions, with drill, order, and obedience;

- Factories, with time discipline, quotas, and supervision;

- Even urban planning, where streets and surveillance cameras create panoptic visibility.

In short, the prison is not the origin of discipline—it is the node where all disciplinary practices intersect and become visible. It functions as a kind of epistemological epicenter: the place where power, knowledge, and subjectivity collide.

5. Theoretical Implications: Power, Knowledge, and Subjectivity

The carceral system, according to Foucault, should not be seen simply as a mechanism of repression. It is a productive force, creating subjects, circulating norms, and manufacturing truths. What appears as punishment is in fact a form of governance.

This is the significance of Foucault’s concept of “biopower” and governmentality, which he develops more fully in later works. In Discipline and Punish , he lays the groundwork: prisons exemplify a new modality of power that is not sovereign but disciplinary—not centered on the king or the state, but diffused across institutions and embedded in daily life.

“The carceral network… imposes on everyone a compulsion for self-control, a perpetual accounting of the self, and submission to norms whose origins remain hidden” (p. 306).

We begin to monitor ourselves, internalize expectations, and conform—not out of fear of violence, but in anticipation of observation.

6. Final Reflections: The Inescapable Machine

Foucault does not conclude with a call to abolish prisons—he offers no utopia. Instead, he exposes the deep-rooted mechanisms of normalization that make the prison inevitable in modern society. The final pages are a warning: the prison persists not because it works, but because it embodies the logic of a society obsessed with order, productivity, and control.

He writes:

“The carceral archipelago extends its networks across the entire social body. It is no longer the law or the sovereign that punishes, but the norm that disciplines” (p. 308).

In this final shift, we see Foucault’s argument in full: we have moved from a society of spectacle to a society of surveillance; from the sword of the king to the gaze of the warden; from the visible brutality of torture to the invisible violence of normalization.

Beyond the Prison

Part IV of Discipline and Punish is not simply about prisons—it is about modernity itself. The prison, for Foucault, is a lens through which we can view the entire disciplinary society. It reveals the hidden structure of power: not loud and tyrannical, but silent and productive; not localized in the state, but embedded in institutions, routines, and selves.

To read Foucault here is to understand that freedom itself may be conditioned by unseen systems of control. The challenge he leaves us with is not to ask how we can make prisons better, but how we might live differently—outside the logic of normalization, discipline, and judgment.

Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Foucault marshals an immense range of historical data, case law, institutional records, and architectural designs to support his claims. However, his style—richly layered, theoretical, often nonlinear—demands patient reading.

His central argument is not just that prisons are oppressive, but that they are logical extensions of a society obsessed with order, visibility, and control. His critique is both radical and unsettling, undermining liberal notions of justice and rehabilitation.

Style and Accessibility

Foucault’s prose, while intellectually rigorous, is not always accessible to general readers. His use of historical anecdotes (like Damiens’ execution) offers visceral entry points into his abstract arguments. Still, his academic density may deter casual readers.

Themes and Relevance

- Surveillance and control (precursors to modern digital surveillance)

- Power and knowledge (how institutions define what is “true” or “normal”)

- Normalization and discipline (especially relevant in today’s debates on policing, education, and workplace surveillance)

Author’s Authority

Michel Foucault was an acknowledged authority on philosophy, sociology, and the history of ideas. His research was deeply interdisciplinary, drawing from archival records, criminology, philosophy, and political theory. His credibility is unmatched in this space.

Strengths and Weaknesses

What Makes Discipline and Punish Compelling and Innovative?

One of the Discipline and Punish’s most striking innovations is its panoramic view of punishment as a cultural and political practice, rather than just a legal or moral one. Foucault brilliantly contextualizes how forms of punishment are historically specific, always entangled with larger systems of economic production, political governance, and ideological control.

His vivid juxtaposition of Damiens’ torture in 1757 with the prison schedule of 1838 offers a haunting metaphor for the shift from spectacle to surveillance, from the body to the soul:

“The condemned man is no longer to be seen… punishment had gradually ceased to be a spectacle.“

Foucault’s concept of “docile bodies” revolutionized the way scholars think about institutional power. His notion that modern punishment isn’t merely about stopping crime, but about producing obedient, efficient individuals, is not only relevant—it’s prophetic.

In the era of AI surveillance, biometric databases, social media scoring systems, and predictive policing, the mechanisms Foucault described are no longer theoretical—they’re daily realities.

Shortcomings and Limitations

However, Discipline and Punish is not without flaws. Critics have pointed out several limitations:

- Lack of empirical grounding: Foucault’s historical references can be sweeping. Though rich in archival data, his book sometimes lacks footnoted precision. Readers seeking detailed statistical validation may find the book frustrating.

- Limited engagement with resistance: While he outlines how systems discipline, Foucault doesn’t offer robust accounts of how individuals or communities resist these systems.

- Obscure prose: His dense, metaphor-laden writing style—though intellectually rewarding—often alienates general readers or newcomers to critical theory.

As historian Peter Gay noted, Foucault’s work “severely damaged, without wholly discrediting, traditional Whig optimism,” but may overemphasize control at the expense of human agency.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence

Contemporary Reception

Upon its release in France in 1975, Discipline and Punish was reviewed across prominent cultural outlets such as Le Nouvel Observateur and Le Monde. It attracted wide attention among intellectuals, scholars, and political theorists.

When translated into English in 1977, it garnered mixed reactions:

- Praised for its originality and breadth,

- Critiqued for its gloomy determinism and lack of attention to real-life complexities.

Still, its academic and cultural impact is monumental. According to law professor David Garland, the most enduring critique has been that Foucault’s model of power is too totalizing—offering little space for human agency or unpredictable variables.

Enduring Influence

Despite this, Foucault’s ideas are deeply embedded in modern scholarship:

- Sociology: Especially studies of surveillance, institutions, and deviance.

- Criminology: Reassessment of the prison-industrial complex.

- Education: Understanding classrooms as spaces of surveillance and conformity.

- Public Health and Psychiatry: Analyzing how bodies are medicalized and normalized.

The concept of panopticism alone has become a powerful metaphor for contemporary society. From CCTV cameras to smartphone data tracking, we now live in what many call “digital panopticons”—echoing Foucault’s insight that “visibility is a trap.”

Key Quotations

Here are some of the most quoted and powerful excerpts from Discipline and Punish:

- On surveillance and control:

“Visibility is a trap.“

This line encapsulates the essence of panopticism—where being seen, or the threat of being seen, becomes a method of control.

- On the shift in punishment:

“The body is caught up in a system of constraints and privations, obligations and prohibitions.“

- On the panopticon:

“The major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.“

- On disciplinary power:

“Discipline ‘makes’ individuals; it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise.“

- On modern prisons:

“The prison functions as an apparatus of normalization.“

Each of these quotations reflects the central thesis of Discipline and Punish: that disciplinary institutions shape individuals not through violence, but through normalization and internalization of societal expectations.

Comparison with Similar Works

Foucault vs. Beccaria

While Foucault dismantles the moral narrative of reform, Cesare Beccaria’s On Crimes and Punishments (1764) is seen as foundational in modern penal reform. Beccaria argued for rational, proportionate punishment. Foucault, by contrast, suggests that even these reforms are new tools of control, not steps toward justice.

Foucault and Bentham

Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon is central to Foucault’s argument. While Bentham viewed it as a humane innovation, Foucault sees it as a symbol of pervasive, internalized control. The same structure celebrated by utilitarians becomes, in Foucault’s eyes, a chilling architectural metaphor for modern power.

Foucault and Marx

Although both critique capitalism, Marx focuses on class struggle, whereas Foucault zeroes in on micro-levels of power and control, including surveillance and normalization. Marx examines economics; Foucault interrogates institutions and epistemes—the systems of knowledge that define what is “true” and “normal.”

Conclusion

Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish is far more than a history of prisons. It’s a philosophical autopsy of modern society, exposing how institutions condition, surveil, and normalize individuals. He compels us to question the very frameworks we associate with justice and progress.

Overall Impressions

Strengths:

- Groundbreaking theoretical framework

- Rich historical and philosophical insight

- Enduring relevance to 21st-century issues

Weaknesses:

- Opaque language

- Sparse engagement with resistance

- Overly deterministic portrayal of power

Who Should Read This Book?

- Academics and scholars in philosophy, sociology, criminology, political science

- Educators rethinking authority and surveillance in learning environments

- General readers with a strong interest in justice, ethics, and institutional critique

For general audiences, a guide or companion read might be helpful, but Discipline and Punish offers a deep, thought-provoking journey into the invisible mechanics of modern power.