The Old Man and the Sea is a short novel written by the American author Ernest Hemingway, first published in 1952 by Charles Scribner’s Sons in New York. At just over 27,000 words, it became one of Hemingway’s most celebrated works, earning him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and contributing significantly to his Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.

The novella has since been translated into dozens of languages and is regarded as a modern literary classic.

Categorized as literary fiction and often aligned with the modernist movement, the The Old Man and the Sea is a prime example of Hemingway’s minimalist style—direct, economical, yet profoundly layered in meaning. The story was inspired partly by Hemingway’s own time in Cuba and his observations of local fishermen in the Gulf Stream.

Historically, it also reflects the post-World War II period, when Hemingway, struggling with his reputation after mixed reviews of earlier works, sought to reassert himself in the literary world. The setting—mid-20th century Cuba—anchors the narrative in a specific socio-economic reality where fishing was both livelihood and metaphor.

At its core, The Old Man and the Sea is not merely a story about an aging fisherman’s struggle to catch a giant marlin—it is a meditation on endurance, dignity, and the human spirit’s capacity to find meaning in suffering.

In my reading, the novella’s strength lies in its deceptively simple narrative that masks an ocean of symbolic depth. Its weaknesses, if any, are tied to its brevity, which leaves some thematic questions tantalizingly unresolved. Yet, this conciseness is also its artistic power: every line carries weight, and every scene has purpose.

Table of Contents

1. Background

Author’s Context

Ernest Hemingway wrote The Old Man and the Sea during a period of personal and professional resurgence. By the late 1940s, his reputation had declined somewhat after the lukewarm reception of Across the River and Into the Trees (1950).

Critics felt he had lost the concise vigor that defined his earlier work. Determined to prove them wrong, Hemingway returned to a style and theme that had always been his strength—stories of resilience, man versus nature, and the dignity found in struggle.

Hemingway was living in Cuba at the time, in a house called Finca Vigía, and he spent many days fishing in the Gulf Stream aboard his boat Pilar. Local Cuban fishermen, particularly Gregorio Fuentes, are believed to have inspired the novella’s protagonist, Santiago.

Historical and Geographical Setting

The story unfolds in a small Cuban fishing village near Havana during the mid-20th century, a time when the fishing economy was central to many coastal communities. The Gulf Stream—teeming with marlin, sharks, and other large fish—serves as both the literal and symbolic arena of Santiago’s epic struggle.

Hemingway’s portrayal reflects the harsh realities of subsistence fishing: the unpredictability of the sea, the economic precariousness of relying on daily catches, and the intimate relationship between fisherman and ocean.

Cultural Significance

Published in 1952, The Old Man and the Sea resonated strongly with Cold War-era audiences. Santiago’s unwavering fight against overwhelming odds mirrored a broader human condition—standing one’s ground despite an uncertain world. The novella was quickly hailed as a return to form for Hemingway, solidifying his literary legacy and reaffirming the values of perseverance, humility, and quiet heroism.

2. Summary of the Book

Plot Overview

Santiago, an aging Cuban fisherman, has gone 84 consecutive days without catching a fish—a streak that has made others in his village consider him salao, the worst kind of unlucky. Once, a young boy named Manolin used to fish with him, but Manolin’s parents have ordered him to work with more successful fishermen.

Still, the boy remains devoted to Santiago, visiting him daily, helping him carry his fishing gear, and bringing him food. Their conversations are peppered with talk of baseball—especially Santiago’s admiration for Joe DiMaggio—offering a glimpse into the old man’s optimism despite hardship.

On the 85th day, Santiago resolves to sail farther into the Gulf Stream than usual. Alone in his skiff, he hooks a massive marlin—a fish so large and strong that it begins to tow the boat out to sea. What follows is a three-day and three-night battle between man and fish, a contest of endurance, skill, and willpower. Santiago respects the marlin deeply, calling it “brother,” and sees it as a worthy adversary rather than just prey.

As the days pass, Santiago’s hands cramp, his back aches, and exhaustion sets in. Yet he refuses to let the line go slack. Hemingway’s minimal but vivid descriptions capture every moment: “Fish,” he says aloud, “I’ll stay with you until I am dead.”

On the third day, Santiago finally kills the marlin with his harpoon, lashing it alongside his skiff. The fish is over 18 feet long, and Santiago calculates that it will fetch a high price at the market. However, blood from the marlin attracts sharks. Santiago fights them with his harpoon, an oar, and even the boat’s tiller, but the relentless attacks strip the marlin to its skeleton.

Santiago returns to the village utterly exhausted, carrying his mast like a cross—an image echoing Christ’s crucifixion. The marlin’s enormous skeleton, still tied to the boat, stirs awe among the villagers. Manolin, moved by Santiago’s perseverance, vows to fish with him again, regardless of his parents’ orders.

Setting

The primary setting is the small Cuban fishing village and the vast waters of the Gulf Stream. The village scenes are intimate and grounded in the realities of rural coastal life—modest homes, tight-knit communities, and a shared dependence on the sea’s bounty. In contrast, the Gulf is a vast, isolating expanse where man’s struggle against nature becomes elemental.

The setting is not merely a backdrop; it functions as a character in itself. The sea shifts between friend and foe—at times providing sustenance, at others challenging Santiago to his physical and emotional limits. The shifting currents, scorching sun, and unpredictable creatures underscore the novel’s themes of resilience, respect for nature, and the inevitability of loss.

3. Analysis

3.1 Characters

Santiago

Santiago is the heart of the narrative—a proud, skilled fisherman whose body has aged but whose spirit remains unbroken. Hemingway portrays him as a man of discipline, humility, and endurance. His relationship with the marlin is one of mutual respect; he calls it hermano (“brother”) and acknowledges its dignity.

Santiago’s suffering—his bleeding hands, the deep pain in his back, the sheer fatigue—becomes symbolic of humanity’s struggle against forces beyond control. His perseverance is not driven by greed but by a desire to prove his worth to himself.

Manolin

The young boy represents loyalty, hope, and the passing of tradition. Although removed from fishing with Santiago by his parents, Manolin never abandons the old man emotionally. He brings him food, coffee, and newspapers about baseball, and in doing so, preserves Santiago’s dignity.

His decision to fish with Santiago again at the novel’s end symbolizes generational continuity and the endurance of mentorship.

The Marlin

The marlin is not a one-dimensional prize but a fully realized presence in the novel. Santiago admires its size, strength, and determination. The marlin mirrors Santiago—both are seasoned, resilient creatures fighting with honor. Its eventual death is bittersweet, signifying victory and loss in equal measure.

The Sharks

The sharks are nature’s opportunists, representing forces of destruction that inevitably follow triumph. They are relentless, indifferent, and serve as a stark reminder that no victory is permanent.

3.2 Writing Style and Structure

Hemingway employs his trademark Iceberg Theory—a minimalist style where the deeper meaning is implied rather than explicitly stated. The prose is direct, stripped of ornamentation, yet loaded with subtext. Dialogue is sparse but revealing, and the narrative alternates between external action and Santiago’s interior monologue.

The novel’s structure is tightly compressed, unfolding over a few days but drawing on a lifetime’s worth of wisdom and struggle. The pacing mirrors Santiago’s ordeal—slow and tense during the marlin’s pull, frenetic during the shark attacks, and meditative in moments of exhaustion.

3.3 Themes and Symbolism

Perseverance and Endurance

The central theme is the dignity of struggle. Santiago’s journey illustrates that worth lies in effort and resilience, not merely in the outcome.

Man vs. Nature

Nature is both adversary and partner. The marlin’s majesty demands respect, while the sharks embody nature’s brutal, uncontrollable side.

Pride and Personal Redemption

Santiago’s pride is not arrogance but a personal standard of excellence. His battle with the marlin becomes a test to reaffirm his identity as a fisherman.

Symbolism

- The Marlin: Nobility, achievement, the ultimate challenge.

- The Sharks: Loss, inevitability of decay, the forces that diminish triumph.

- The Mast: Echoes of the cross, linking Santiago’s suffering to Christ-like endurance.

- The Sea: The eternal stage for human endeavor, unpredictable and vast.

3.4 Genre-Specific Elements

As a literary novella, The Old Man and the Sea excels in tight focus, character depth, and thematic richness. The world-building is subtle but immersive, anchored in authentic depictions of fishing life and the Gulf Stream’s ecosystem. Hemingway’s dialogue is economical yet vivid, and his adherence to realism keeps the story grounded.

Recommended for: Readers interested in literary fiction, maritime adventure, philosophical tales of endurance, and those exploring Nobel Prize-winning literature.

4. Evaluation

Strengths

- Emotional Depth in Simplicity – Hemingway’s sparse language belies the emotional intensity of Santiago’s journey. The novella resonates deeply without the need for complex plot twists.

- Symbolic Richness – From the marlin to the mast, symbols are layered yet accessible, offering multiple interpretations for readers of different backgrounds.

- Universal Themes – Struggle, pride, dignity, and the passage of knowledge from one generation to another make The Old Man and the Sea timeless.

- Authentic Detail – The fishing techniques, ocean currents, and weather patterns are portrayed with a level of detail that grounds the narrative in reality.

- Compact Narrative – At around 27,000 words, the story’s brevity enhances its intensity, making it both approachable and impactful.

Weaknesses

- Minimalist Style Not for Everyone – Readers who prefer lush, descriptive prose or complex subplots might find the style overly plain.

- Limited Supporting Cast – Aside from Santiago, Manolin, and symbolic presences like the marlin and sharks, there is little character variety.

- Pacing Challenges – The prolonged battle with the marlin, while deliberate, may feel slow to readers accustomed to fast-moving narratives.

Impact

Reading The Old Man and the Sea is less about the suspense of “what happens next” and more about the emotional resonance of the journey. Santiago’s struggle becomes a mirror for our own battles in life—against circumstances, time, or inner doubts.

The novella’s enduring popularity is reflected in its sales and academic adoption. It was a major factor in Hemingway being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. Its narrative of perseverance continues to be cited in motivational contexts, sports psychology, and leadership training.

Comparison with Similar Works

Thematically, the novella can be compared to:

- Moby-Dick by Herman Melville – Both pit a man against a great sea creature, though Melville’s is more about obsession and fate, while Hemingway’s focuses on dignity and endurance.

- To Build a Fire by Jack London – Another tale of man vs. nature, emphasizing survival, resilience, and humility before nature’s power.

- Life of Pi by Yann Martel – Shares a spiritual and symbolic dimension in a survival-at-sea setting.

Reception and Criticism

Upon release in 1952, the novella was hailed as a return to form for Hemingway after mixed reviews of his previous works. Critics praised its clarity, moral weight, and humanity, while some argued its allegorical layer was too direct. Nonetheless, it quickly became a bestseller and remains one of the most taught works in literature classes globally.

Adaptation

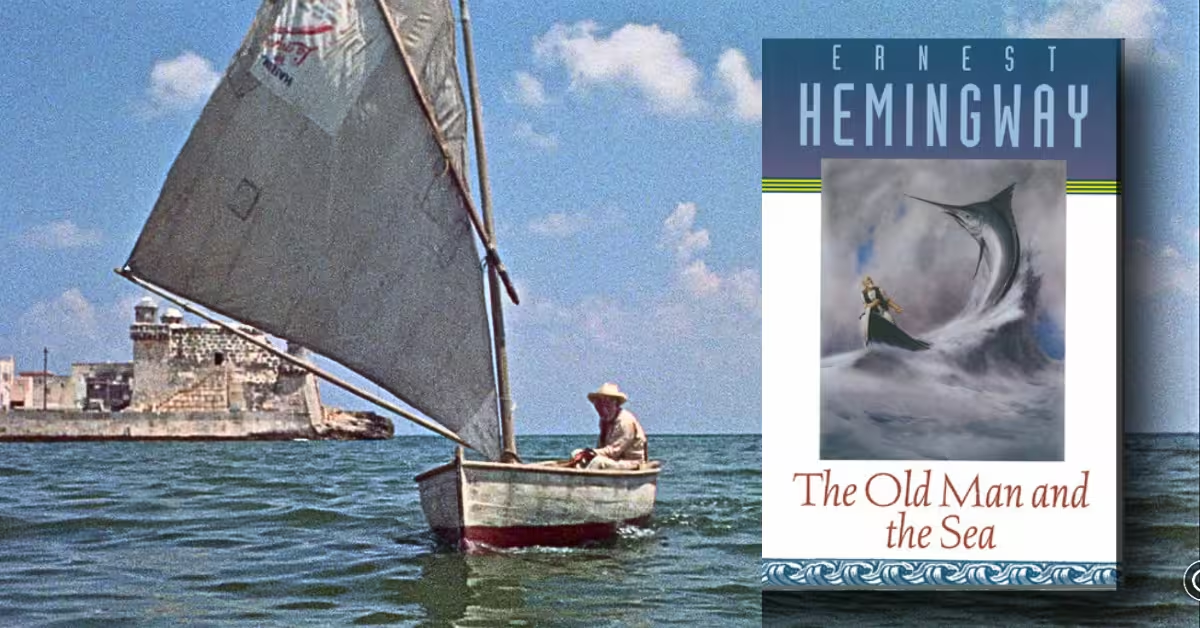

The novella was adapted into films, including the 1958 version starring Spencer Tracy, which earned Academy Award nominations. Animated versions and stage adaptations have also brought Santiago’s story to new audiences.

Notable and Useful Information

- In Cuba, where Hemingway lived for two decades, Santiago is seen as a symbol of the Cuban fisherman’s spirit.

- Many fishing veterans have attested to the authenticity of Santiago’s techniques.

- In sports, the novella is often referenced in relation to the “last stand” of legendary athletes.

5. Personal Insight with Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading The Old Man and the Sea today is more than revisiting a mid-20th-century literary classic — it’s engaging with a living metaphor for perseverance, skill mastery, and personal dignity in a rapidly changing world.

5.1 Lessons in Perseverance and Resilience

Santiago’s battle with the marlin over three grueling days mirrors the resilience gap many face in our time. According to a 2023 World Economic Forum report, 56% of employees globally feel “burned out” due to work demands, yet resilience training and mental health literacy programs are still underutilized in most educational settings.

Santiago’s story offers a narrative framework for teaching grit and long-term goal focus — skills identified by psychologist Angela Duckworth as critical for achievement.

5.2 Intergenerational Learning

The bond between Santiago and Manolin showcases the apprenticeship model of skill transfer — an approach that is losing ground in the digital era. UNESCO data (2022) shows that hands-on vocational learning in fishing, farming, and crafts has dropped by 32% globally in the last two decades.

This novella can be used in classrooms to inspire mentorship culture in industries where generational skill loss is becoming a crisis.

5.3 Respect for Nature

Hemingway’s portrayal of Santiago’s respect for the marlin reflects ecological consciousness far ahead of its time. In an era of overfishing — with the FAO reporting that 34.2% of global fish stocks are overexploited — literature like this can foster marine stewardship values.

For environmental education, Santiago’s ethos (“I love you and respect you very much. But I will kill you dead before this day ends.”) creates a powerful paradox about coexistence and survival.

5.4 Educational Use in Leadership Programs

In leadership courses, Santiago’s journey can be dissected as a case study in ethical leadership — pursuing excellence without arrogance, and accepting loss without self-pity. Business schools increasingly adopt storytelling in leadership training, and The Old Man and the Sea provides a text rich in discussion points: risk assessment, endurance, and post-victory humility.

5.5 Socioeconomic Reflection

Santiago’s poverty reflects the lived reality of many small-scale fishers today. The World Bank (2021) estimates that 90% of the world’s 120 million fisheries-related workers are small-scale, often in precarious economic conditions.

This offers a discussion bridge for economics, sociology, and environmental science classes, blending literary analysis with real-world development challenges.

10 Life Lessons from Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea

Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea is more than just the story of an aging fisherman battling a giant marlin in the Gulf Stream.

First published in 1952 and awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953, this short novel distills a lifetime of wisdom into a simple but powerful narrative. Through Santiago’s courage, endurance, and humility, Hemingway gifts readers timeless insights into the human condition.

Below are ten profound life lessons from The Old Man and the Sea that resonate just as strongly today as they did over seventy years ago.

1. Persistence is Power

Santiago, the “old man,” hasn’t caught a fish in 84 days, yet he sets out again with quiet determination. His mindset teaches us that persistence is not about instant success—it’s about refusing to quit when the odds seem impossible. As Hemingway writes, “A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”

2. Respect Your Adversary

The marlin is not just a fish; it becomes Santiago’s worthy rival. He admires its beauty, strength, and dignity. In life, this reminds us to respect our challenges and even our competitors, as they bring out our best qualities.

3. True Success Requires Sacrifice

The old man’s body is pushed to its limits—bleeding hands, aching muscles, sunburned skin—yet he continues. Every worthwhile goal comes with a price, and sacrifice is often the currency of achievement.

4. Solitude Can Build Strength

While isolation can be difficult, Santiago’s time alone at sea forces him to confront his fears and limitations. Modern life may be noisy and crowded, but carving out moments of solitude can help us reconnect with our inner resilience.

5. Nature is Both Ally and Opponent

Hemingway’s descriptions of the sea show it as beautiful yet merciless. The lesson: nature doesn’t play favorites. We must adapt, respect, and work with it, whether in fishing, farming, or our broader environment.

6. Pride Can Be Noble—If Controlled

Santiago’s pride is not arrogance; it’s a quiet, internal force that keeps him striving. He says, “I must hold him all the night and be strong and never let him go.” Pride, when rooted in self-respect, can be a powerful motivator.

7. Loss Doesn’t Erase the Value of the Struggle

Despite his victory over the marlin, sharks strip it to the bone before he returns to shore. The world often measures success in tangible results, but the journey and the growth it brings are equally valuable.

8. Mentorship is a Lifelong Legacy

The relationship between Santiago and the boy, Manolin, symbolizes the passing of wisdom. Investing in others—especially the next generation—is a way to ensure that our struggles and victories continue to have meaning.

9. Physical Limits Can Be Overcome by Mental Strength

Santiago is old, frail, and physically exhausted, but his willpower keeps him going. This is a reminder that mental toughness often determines how far we can truly go.

10. Dignity Exists Even in Defeat

Though he returns with only the marlin’s skeleton, Santiago holds his head high. Defeat in the eyes of others does not mean defeat in your own heart. Maintaining dignity in loss is one of the purest forms of victory.

Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea is more than a fishing tale—it’s a blueprint for perseverance, humility, and the quiet power of the human spirit. Santiago’s story encourages us to face our own “marlins” in life with courage, respect, and unwavering resolve.

As readers, we carry away not just an image of a man in a skiff battling a fish, but the enduring truth that effort, character, and dignity are victories in themselves.

Personal Reflection

From my reading, Santiago’s solitude resonated most deeply during the long, silent stretches of the sea.

It reminded me of the emotional stamina needed in modern personal and professional life — moments when no one is watching, when validation is absent, and yet we must still row forward. It’s this interior victory, often invisible to the world, that makes Santiago’s journey timeless.

6. Quotable Lines

Hemingway’s prose in The Old Man and the Sea is deceptively simple yet rich with layers of meaning.

6.1 On Perseverance

“But man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”

This is arguably the most quoted line from The Old Man and the Sea and has become a universal mantra of resilience. It encapsulates Santiago’s indomitable spirit.

6.2 On Love for Nature

“Fish, I love you and respect you very much. But I will kill you dead before this day ends.”

A paradoxical declaration that reflects Santiago’s reverence for life even in the act of taking it — perfect for discussions on sustainability and moral dilemmas.

6.3 On Solitude

“He was comfortable but suffering, although he did not admit the suffering at all.”

This line captures the quiet stoicism that defines Santiago’s journey and resonates deeply with readers enduring private struggles.

6.4 On Dreams and Symbolism

“He no longer dreamed of storms, nor of women, nor of great occurrences, nor of great fish, nor fights, nor contests of strength, nor of his wife. He only dreamed of places now and of the lions on the beach.”

A poetic insight into Santiago’s inner world, connecting youth, memory, and hope through recurring dream imagery.

6.5 On Determination

“I may not be as strong as I think, but I know many tricks and I have resolution.”

A testament to skill, experience, and mental endurance over sheer physical power.

6.6 On Endurance

“It is silly not to hope. Besides I believe it is a sin.”

This brief but profound reflection emphasizes hope as a moral and spiritual necessity.

6.7 On Human Dignity

“Now is no time to think of what you do not have. Think of what you can do with what there is.”

A philosophy of resourcefulness and adaptability — applicable beyond the sea to business, education, and life.

6.8 On Respect Between Man and Nature

“You did not kill the fish only to keep alive and to sell for food, he thought. You killed him for pride and because you are a fisherman.”

Highlights the intertwined motives of survival, identity, and personal pride.

6.9 On Wisdom from Experience

“Every day is a new day. It is better to be lucky. But I would rather be exact. Then when luck comes you are ready.”

Blends the concepts of preparation and fortune — a valuable lesson for any field.

6.10 On the Essence of the Struggle

“A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”

Repeated for emphasis, as this line embodies the novella’s philosophical core and remains Hemingway’s gift to motivational literature.

7. Conclusion

Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea is not merely a story about an old fisherman battling a marlin — it is a distilled parable of human endurance, dignity, and the quiet heroism found in perseverance against overwhelming odds. Through Santiago’s solitary struggle, Hemingway delivers a narrative where every wave, every pull on the fishing line, and every fleeting dream carries symbolic weight.

The novella’s strength lies in its economy of language and depth of meaning. It resonates universally because it taps into timeless truths: the inevitability of struggle, the necessity of hope, and the bittersweet victories that define a life well-lived.

Santiago’s journey is one where loss is inseparable from triumph — the marlin is won through skill and resolve, but ultimately consumed by sharks, leaving only its skeleton as a testament to the fisherman’s courage. In this, Hemingway reframes victory: it is not in the possession of the prize, but in the nobility of the effort.

For readers, The Old Man and the Sea remains an essential literary experience. It is equally a meditation on man’s place in nature and a guide to living with integrity when confronted with defeat. The novella’s enduring appeal, recognized with the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and contributing to Hemingway’s Nobel Prize in 1954, is proof of its literary immortality.

I recommend The Old Man and the Sea to students of literature, aspiring writers, and anyone seeking a philosophical yet accessible reflection on resilience. For educators, it offers an opportunity to discuss themes of courage, environmental ethics, and existential meaning. For the casual reader, it is a short yet unforgettable journey into the heart of human endurance.

fiction, Nobel Prize, classic literature, inspirational novels, man vs nature, Pulitzer Prize winner, resilience, literary symbolism