Grief scrambles memory, and Flashlight by Susan Choi shows how a family spends decades trying to see in the dark. The novel tackles a problem most books only skirt: how do you trust what you remember—especially when your story begins with a vanishing?

Flashlight by Susan Choi is a multi-generational literary novel about a girl whose father disappears on a night walk by the sea, and the fractured memories, identities, and histories (Japanese, Korean, and American) that ripple from that one event.

Choi seeds the mystery with precise images—the way the “flashlight…landed almost noiselessly in sand,” repeated like a ticking metronome of doubt ; a child psychologist’s comic-ominous prop (“‘It’s to see in the dark!’”) ; and the father’s last words before the night turns. “Someday, you’ll feel thankful to your mother. But I want you to act thankful now,” the scene ends: “These are the last words he ever says to her.”

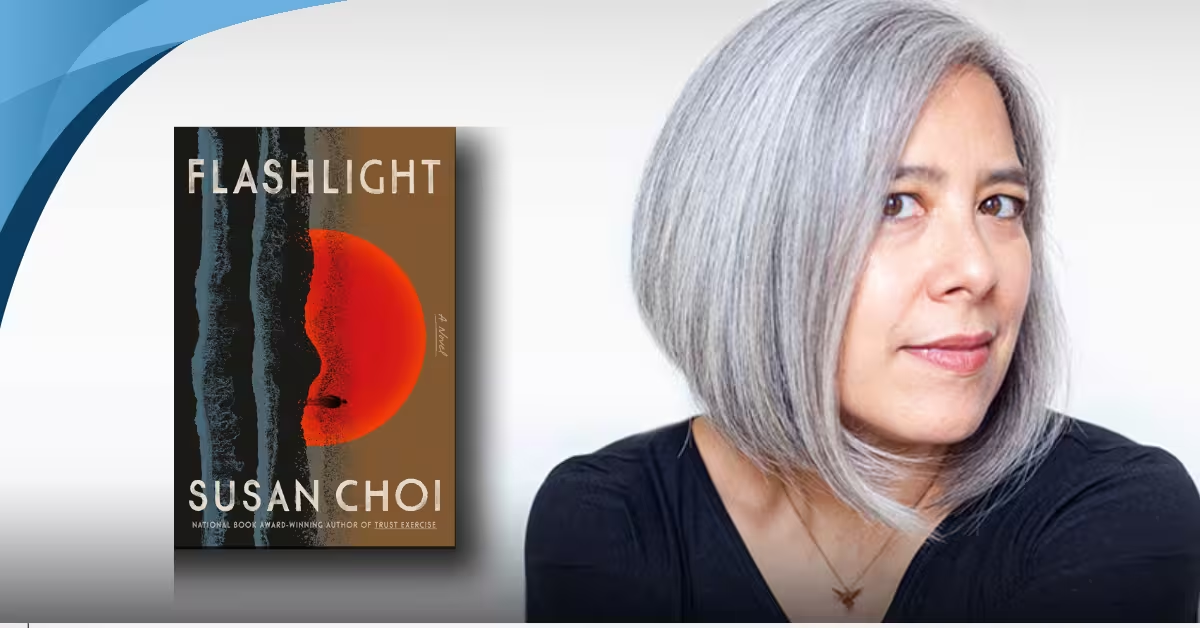

Beyond the text, reviews and prize lists situate the book: release by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on June 3, 2025 (also Jonathan Cape in the UK) and a 2025 Booker shortlist nod coverage in The Guardian, TLS, and Chicago Review of Books praises its scale and memory-core

Best for readers who love literary realism with historical reach, family sagas, and formally daring memory studies; not for those seeking a neat whodunit or a brisk thriller—Flashlight by Susan Choi is patient, digressive, and emotionally meticulous.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Flashlight (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, first edition 2025 is Susan Choi’s sixth novel, published in the U.S. by FSG and in the UK by Jonathan Cape; it later landed on the 2025 Booker shortlist.

From its opening pages, Flashlight by Susan Choi establishes an eerie clarity: ten-year-old Louisa walks the breakwater with her father while her mother stays inside, unwell.

The father admits he never learned to swim; the child pushes back; the evening pales, then darkens. “They’ll turn back soon,” the narrator says, and then he delivers the admonition that will echo for hundreds of pages: “Someday, you’ll feel thankful to your mother. But I want you to act thankful now.”

By sunrise, Louisa is found on the sand; her father is gone. Adults explain it tidily—currents, shock—but Choi keeps tilting the scene to show how story hardens too quickly into certainty: “Her father…had not been found at all…The flashlight had landed almost noiselessly in sand.”

2. Background

Choi builds Flashlight by Susan Choi on real historical crosscurrents: postwar Japan’s coastal life, the Zainichi (ethnic Koreans in Japan), and the late-1970s abduction scare tied to North Korean kidnappings.

Her acknowledgments cite key nonfiction—The Invitation-Only Zone; Nothing to Envy; Exodus to North Korea; The Aquariums of Pyongyang; and more—signaling the research spine under the fiction.

Historically, Japan officially recognizes 17 abductees but investigations and testimony point to hundreds of suspected cases, a human-rights crisis still unresolved decades later; the topic remains a live wire in Japanese politics and in UN fora.

3. Flashlight by Susan Choi Summary

The novel opens on a memory that isn’t quite a memory: ten-year-old Louisa and her father walk a breakwater in their summer town; he is cautious, dressed in slacks and hard shoes, holding her hand in one palm and “a flashlight which is not necessary” in the other—until darkness falls, the rocks turn slick, and the flashlight suddenly matters.

He tells her she should “act thankful” to her mother—“These are the last words he ever says to her”—and soon after, he is gone, presumed drowned; only later will the stray, stubborn fact return to Louisa: the dropped flashlight didn’t clatter or splash. “It landed almost noiselessly in sand.”

In Los Angeles, not long after the disaster, Louisa is taken to a school psychologist, Jerry Brickner. She parries his questions, fixates on the emergency flashlight in his office, and—after coaxing him to dim the room—pocket-steals it.

When Brickner steers gently toward the trauma (“Normal life turning strange—did that feel really real?”), Louisa drops the flashlight with a crack and goes mute. Brickner says he’s heard that, when she was found on the beach in Japan, she told rescuers her father had been “kidnapped.” Louisa denies it, insists her mother “makes everything up.”

The scene embeds two motifs that will govern the book: light and theft. Kidnapping, Brickner pointedly suggests, is a kind of stealing.

From this bright, unnerving overture, the narrative wheel clicks backward into deep history and forward into murk: Flashlight will braid the story of Louisa’s missing father—born with one name, passed through others, and known by many—as it intersects with nations, wars, borders, and the clandestine machinery of disappearance.

We move to Part I: Seok (also called Hiroshi as a child in occupied Japan), beginning in 1945 with a boy in a port slum discovering school, language, and names.

He is Korean by blood, Japanese by coercive naming, first “Hiroshi,” then told the truth of being “석”—Seok/Kang—when a street parade shouts that “Korea is free,” its Taegukgi flag streaming.

The sections build his origin: Zainichi Korean childhood amid war’s end, makeshift homes, a beloved sensei, and the revelation that Jeju, his parents’ island, isn’t one of the “many thousands” of Japanese islands after all but a Korean island hanging like a “fallen-off toenail” from the map. These pages seed the novel’s obsession with renamed people and redrawn maps.

Later sections carry Seok through postwar displacements, migration, study, and eventual life in America under yet another name.

He marries Anne in the U.S., becomes the wary, exacting father we met—one who pokes through Louisa’s food, fears traffic even on sidewalks, insists on the flashlight at dusk. “He must have feared darkness,” Louisa thinks, “always bringing that flashlight despite how long the sunset lived in the sky.” This fear becomes the hinge of fate on the breakwater night.

Then comes the disappearance. The official story is banal: her father slipped, fell, drowned; his body never found; Louisa washed up unconscious.

But the physical detail of the light—no splash, no clatter; sand—sows her lifelong counter-narrative, one she won’t admit even to Brickner: that something else happened on that rock causeway, something like an extraction. “The flashlight had landed almost noiselessly in sand”—that line pulses through her life, the book’s title turning into an epistemological riddle: what did the light actually illuminate?

The novel then swivels to a sprawling, geopolitical middle, where Choi refracts the personal mystery through activists, exiles, diplomats, and con men moving between China, South Korea, Japan, and the United States across decades. Two new presences dominate:

First, Ji-hoon, called the Fisherman, a South Korean abductees’ activist living in semi-hiding in China, who has dedicated his life to tracking people snatched across borders—among them, his own father.

He becomes caretaker to a cantankerous, half-broken old man he nicknames the Crab: a barefoot, senescent escapee who walked out of North Korea with “only the clothes on his back,” who curses in fluent English, and who sometimes raves about Anne and Louisa.

Ji-hoon initially assumes this is a foggy fantasy; then one night the Crab sobs that “even my child is gone,” and his story starts to cohere into something astonishing: he is a Zainichi Korean, born in Japan, later a U.S. permanent resident married to an American woman, abducted decades ago with his little daughter.

Ji-hoon, who has trained himself to be skeptical even of grief, test-questions the Crab; the old man vacillates, at times a vicious bigot, at times a professor scolding an invisible class (“introductory shit with these assholes who don’t know anything!”), at times a father hurrying home to Anne and Louisa because “Louisa has school tomorrow!”

The cognitive weather shifts minute to minute; Ji-hoon learns to lie tenderly (“snowed all night… classes are canceled”) to usher him to calm. The accumulation of details—“my American wife,” the classroom cadence, the names—finally convinces Ji-hoon that this “cover story” is no cover at all. The Crab is real; the past is real; Louisa is real.

Second, Roger, a retired U.S. State Department Asia hand who now conducts a kind of private, extragovernmental human-rights diplomacy. Ji-hoon meets him via a reporter and a CIA contact; Roger is dogged by a separate case—the vanished American backpacker whose witnesses “within a month… all changed their stories”—and he half believes North Korean agents still prowl far-flung borders.

Ji-hoon scoffs at the plausibility—“tigers ate him?” he suggests—but uses the opening to ask Roger’s help for his friend: an escaped DPRK prisoner who claims to be a U.S. green-card holder with an American wife and a daughter named Louisa. Roger studies the Crab’s photo far longer than the backpacker’s.

The impossible begins to look actionable.

As these back-channel connections click into place, the book pauses over a watershed in real history: September 2002, when North Korea admitted to abducting thirteen Japanese civilians decades earlier.

Five came “home” for a tightly choreographed visit; eight were declared dead. For Ji-hoon and his network, the acknowledgement was paradoxical: it proved the pattern they’d shouted about for years while also tempting the world to consider the matter “officially closed.” A photo-op “resolution” that left countless other families abandoned in silence.

Out of that silence, Louisa’s story re-enters with a jolt. Part VI: Louisa returns us to the beach with her father—“The beach quickly grows wider and wilder”—a lyrical reprise that now reads like a memory-trace guiding her back across continents.

The older Louisa travels to Seoul, taking leave from her life (and from Tobias, a friend/partner back home) for what becomes nearly twelve weeks, to meet with Roger and a Korean fixer named Miss Yi and to visit a man who sometimes knows her name. He calls her “Louisa,” asks “How is school,” and even, once, asks about “Anne,” as if the past were a room he can only crack open for a second at a time.

Louisa’s reunion is not cinematic. The Crab—now identified to us as her father—recognizes her sometimes, thinks she is “someone named Seung” other times, and often slides into a docile, wind-up mode, saying “Thank you!” with a jangly cheer that breaks Louisa’s heart.

She confides to Tobias by phone that he “was not even slightly surprised” to see her; perhaps he had held her image so long that recognition had ceased to be an event and become a weather system. The bureaucracy around him churns: Where should he go?

What name can he lawfully use? Does the United States owe him a life it helped expose and then forgot? Louisa sits with Roger in a Buddhist restaurant, looking out over a temple’s pagoda tree, and realizes the most likely outcome: “He’s going to solve this problem—of where and how he should move—by not moving.”

What happened back then? Choi never delivers a dossier’s certainty, but the web of testimony hardens into a version we can live with.

On that last summer night in Japan, agents took Seok (Louisa’s father) and also took Louisa, spiriting them toward the DPRK. Somewhere in the choreography, Louisa was separated, later found on a nearby beach in shock—hence the early report that she’d said “kidnapped”—while Seok/Serk vanished into the frozen hinterland of labor camps and administrative non-existence. Years were lost.

The Crab’s senility is less a veil than the toll of decades of coercion, hunger, and the enforced un-naming that makes a person a blank. Ji-hoon’s life’s work, Roger’s quiet conduit, and Louisa’s stubborn, private deduction (the soundless flashlight) converge to retrieve a living remnant—her father—just in time for the book to ask what “retrieval” can really mean.

The novel’s last movement is both reunion and reckoning. Louisa visits rooms where her father sits, eats, stares; she talks to Tobias about the miracle and its limits; she attends meetings with Miss Yi at various ministries and stares at the hulking U.S. Embassy in Gwanghwamun, its soot-filmed compressors exposed “as if to say” that real power doesn’t need to be tasteful.

The rainy season creeps toward its end; Louisa counts the weeks and imagines the rest of her life in the shadow of a recovered father who no longer knows time. There’s no triumph here—just paperwork, caretaking, and a soft, persistent light.

Detailed arc, end to end

The breakwater and the light. Father and daughter cross the rocks; he insists on caution, on the flashlight; his final admonition (“act thankful”) lands with the weight of a benediction.

Hours later he is gone; only the strange physics of the dropped light—sand, not stone, not sea—refuses to make sense. Louisa’s mind converts this into a private theorem that the official story cannot account for.

California: the psychologist and the stolen torch. In Los Angeles with her ailing mother and caretaking aunt, Louisa meets Dr. Brickner, who lets her play with a flashlight during their “grade-level” appointment. He knows about the Japan beach and the rumor that Louisa said “kidnapped.” Louisa denies it—but then literally steals his light, as if to keep hold of the only tool that can make sense of darkness.

Origins: Seok/Hiroshi. We plunge into Seok’s childhood in Japan at the messy end of empire. He learns that his “real” name isn’t Hiroshi; it’s 석/Seok. Jeju is not Japanese after all. The chapter foreshadows everything the novel will do with naming, nationality, and the violence of bureaucratic re-labeling—how maps can falsify a person.

Abduction as policy. Decades later, North Korea’s 2002 acknowledgment that it abducted thirteen Japanese citizens confirms the shape of a horror that’s already defined Ji-hoon’s life.

The “resolution” leaves most abductees—and many South Koreans—unaccounted for. This geopolitical background quietly validates the most far-fetched version of Louisa’s story.

China: the Fisherman and the Crab. Ji-hoon shelters a volatile, dignified wreck of a man—the Crab—whose mind toggles through languages and lives: he is a teacher (“introductory shit”), a father worried that “Louisa has school tomorrow,” an American green-card holder, and a stateless Korean who’s lost everything.

The old man breaks down weeping: “When I have nothing? When even my child is gone!” The Fisherman starts to believe.

The back-channel. A CIA acquaintance and a reporter connect Ji-hoon with Roger, who is chasing a different disappearance in China; Ji-hoon argues it’s “the least plausible explanation” that North Koreans took that particular kid, then pivots: can Roger help with a man who walked out of North Korea, claims a U.S. life, and a missing daughter named Louisa? Roger takes the Crab’s photo and doesn’t let it go.

The network begins to do what governments won’t.

Part VI: the return to Louisa. The narrative splices back to the beach, then to present-day Seoul. Louisa visits her father in a liminal care setting; sometimes he calls her name, sometimes he thinks she is “Seung.”

The reunion is oblique and real: he asks “How is school,” a gentle, unconscious parody of an American father; once he asks after Anne.

Louisa meets Roger “at the US Embassy building” and eats with him near a Buddhist temple; she concludes that the unsolvable logistics of citizenship, care, and age may be “solved” by staying put.

The ending (explained): Flashlight refuses the tidy closure of courtroom or courtroom-style revelations. Instead, it offers embodied knowledge: Louisa has found her father; the man lives; he speaks sometimes; he is and isn’t the person she lost.

The old mystery of the soundless light has been transmuted into a practical ethic—care work in the half-light—where “truth” isn’t a document but an ongoing presence.

Louisa may return home; Roger will keep nudging ministries; Ji-hoon will chase the next faint signal. But the book’s last emotional move is acceptance: of the father who stays, of a life that will be lived with him not moving, of a story that won’t resolve but can still be inhabited.

4. Flashlight Analysis

4.1. Flashlight Characters

Louisa, the bright child at the book’s heart, meets the adult world’s tidy narratives with prickly skepticism. In Dr. Brickner’s office, she mocks compliments (“I’m too smart for compliments”), questions morality (“I don’t see why [stealing is] wrong”), and tests power by stealing the titular flashlight.

Choi renders her intelligence with a razor’s edge: she watches adults as if they’re on stage, swapping pity, contempt, and pity again; the flashlight’s “pale cloud of light” becomes both toy and talisman, a portable uncertainty.

Serk (born Seok), the father, is love as vigilance. He studies tide tables, double-checks math, and teaches astronomy while policing risk: “Love, for Serk, always flowed first through authority’s channel.” He is besotted, careful, and finally swallowed by a night whose rules he thought he had mastered.

Anne, Louisa’s mother, is neither saint nor villain. In one breath she is resented; in another, she’s the parent who taught Louisa to swim—ironically, the one skill the father most feared. Choi gives her vulnerability (the wheelchair scenes) and opacity, letting the child’s perspective bruise the portrait without pinning it down.

4.2. Flashlight Themes and Symbolism

Memory vs. story: Flashlight by Susan Choi returns obsessively to the non-sound of the dropped flashlight—“no clatter,” “no splash,” only sand—as a negative image of knowledge. That void questions whether the official explanation (accident, shock) fits the facts or merely calms the adults.

Language and translation: scenes move among Japan, Korea, and the U.S.; characters translate newspapers, family lore, and themselves. Even Serk renames himself “for an American reality that resists him,” as reviewers note, aligning identity with survival in migration.

Control vs. care: Serk’s pedagogy (“spring tide,” “constellation wheel”) doubles as a spell against chaos, yet love cannot insure the world. The flashlight—a device to “see in the dark”—becomes a moral instrument that sometimes blinds: what we aim at reveals us.

5. Evaluation

Strengths / pleasant surprises. Choi’s precision is thrilling: from the “frail jellyfish of light” on a child’s ceiling to Brickner’s blinds that “screamed in protest,” every sensory cue tightens theme and plot. The novel’s structure—parts cycling through Seok/Serk, Anne, Louisa, Tobias—accumulates perspective without sacrificing momentum.

Weaknesses / friction points. Some will find the book’s deliberately unresolved questions frustrating; its metafictional shift mid-course (flagged by critics) may jar readers who want a strictly mimetic family chronicle. Yet that risk is the price of its moral scope.

Impact. As a reader, I felt my own impulse to “explain” grief slow down. The novel asks us to test every tidy sentence against the sand-softened facts: “There had been no clattering…no splash…The flashlight had landed almost noiselessly in sand.”

Comparison with similar works. If you admired the perspectival play of Trust Exercise, you’ll recognize Choi’s signature dismantling of certainty; if you gravitate to family epics like Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko for their global-historical arcs, Flashlight by Susan Choi offers a tighter, more memory-driven echo.

For readers of North-Korea-focused narratives (e.g., The Orphan Master’s Son), Choi’s approach is less geopolitical thriller, more intimate moral x-ray. (See also Choi’s research nods to abduction literature.)

6. Personal insight

Educators and book-club leaders often ask how to anchor literature to real-world inquiry without instrumentalizing the art.

Flashlight by Susan Choi is a terrific case study: it opens pathways into media literacy (how stories of disappearance are framed), migration studies (Zainichi identity), and trauma psychology (child testimony).

A short module could pair Chapters 1–2 with current summaries of the abduction issue in Japan and prize coverage that captures the book’s themes while inviting students to catalog narrative gaps in the opening breakwater scene.

7. Conclusion

Ultimately, Flashlight by Susan Choi solves the “problem” of grief-narrative not by closing the case but by teaching us how to read uncertainty. The book shines its beam through memory’s particles—dust, tide, rumor, translation—and lets us see their drift.

Recommendation. Highly recommended for readers of literary fiction who appreciate layered structure, historical texture, and moral inquiry; less suited for those who need mystery answers delivered with procedural finality.

If you like Trust Exercise or Pachinko, or you’re curious about stories that cross the Japan-Korea-U.S. triangle, Flashlight by Susan Choi earns a place on your list. (Publication details: FSG first edition, 2025.)