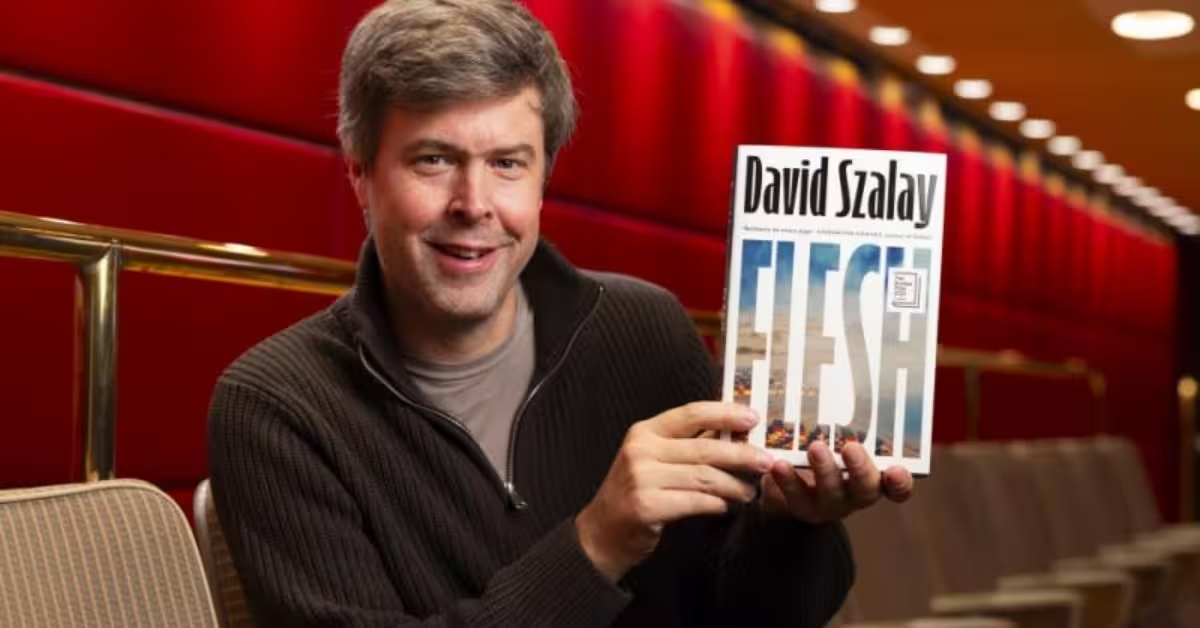

We live with bodies that remember what our minds try to forget, and Flesh by David Szalay shows how that memory quietly rewires a life.

If you’ve ever wondered why one early wound keeps echoing through jobs, love, money, even country, this book is the closest thing to an MRI of cause and effect I’ve read.

A single boundary-crossing encounter in adolescence splinters a Hungarian boy’s sense of self and, through years of silence, sex, work, migration, and war, shapes the man he becomes.

Publication confirms the novel’s 2025 release (Jonathan Cape UK; Scribner US), underscoring its contemporary lens on masculinity and money, and its Booker Prize recognition has drawn wide critical attention. David Szalay won Booker Prize for Flesh in 2025.

Flesh Best for readers of austere literary realism who appreciate close-up observation of class, bodies, and consequence; not for those seeking plot pyrotechnics, tidy catharsis, or a feel-good arc.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Flesh is David Szalay’s 2025 novel, originally published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape and in the United States by Scribner (first US hardcover, April 2025).

Szalay follows István from a tower-block adolescence in Hungary to adult years marked by migration, military contracting, uneven intimacy, and the gravitational pull of money and power.

Flesh’s premise is disarmingly simple: one harmful relationship leaves residues that harden over time, becoming the shape of a life.

Critics have tied Flesh to Szalay’s signature interests—male solitude, the price of status, and the body’s stubborn truths.

2. Background

Szalay writes a Europe that feels economically exact and emotionally off-kilter, and here the early 2000s–2010s milieu—EU peripheries, quick-money schemes, soldiers of fortune—sets the social weather.

The novel’s early chapters anchor us in stairwells, half-landings, and fluorescent classrooms—spaces of transition that never quite deliver arrival. Consider the biology lesson on “fitness,” which reframes survival as reproduction rather than longevity: “modern evolutionary theory defines fitness… by how successful it is at reproducing.”

That cool, textbook voice haunts the hot, private story of how people use, need, and abandon each other.

3. Flesh Summary

István grows up with his mother in a drab Hungarian housing estate where stairwells, landings, and the half-light of shared corridors shape how he understands intimacy and danger.

A middle-aged neighbor across the hall asks his mother if he can help her with weekly shopping; his mother insists he do it because the neighbor has “been very helpful to us.” Each errand ends in the neighbor’s kitchen, where she serves him Somlói galuska, a detail of ordinary hospitality that reassures him even as it blurs a boundary: “Can I kiss you?” she asks, then lets her lips “lightly touch his for a moment,” apologizes, and sends him away.

The shopping continues, and so does the transgression. She positions his body and her own with almost clinical precision—“Like that. There. Like that.”—and initiates sex in an atmosphere of quiet secrecy that excludes the mother, classmates, and any shared language for what is happening. Later episodes repeat the pattern of sweets, silence, and touch.

In biology class, meanwhile, he hears the lesson that modern evolutionary theory defines “fitness” not as longevity but as reproductive success—a cooling textbook logic that shadows the heat of what the neighbor is teaching him with her hands.

The motif is set: stairwell plants, the half-landing’s low window, and the language of “thank you” stand-in for consent where none exists.

As the affair fragments, he begins to patrol the stairs waiting for her, insisting “I want to see you.” She rejects him—“You have to stop this”—and when he later forces a confrontation at her door, her husband appears. There is pushing, a struggle, and the husband falls down the stairs, striking his head on the handrail; he lies “on the concrete floor of the half-landing, next to his wife’s plants,” and does not get up.

Shocked, István walks away, is picked up by police, and hears an officer say, “No, he killed someone,” before a detective informs him that the man is dead. Under questioning, he begins to doubt his own memory—“He starts to wonder if he is remembering it right or not”—and even to believe the officer’s suggestion that he intended to kill the man. What follows is a Sisyphus-like interior trial: he both did and did not mean it, both wanted and did not want the death. The novel doesn’t tidy that knot; it makes you sit in it.

After school he drifts. A tentative lake-day with Noémi at Balaton reveals how inexperienced and needy he feels; their banter about sex and porn—her frankness, his embarrassment—exposes the hollow where healthy adolescence should be. He cannot hold her, cannot hold anyone, and a period of listlessness ends with his mother’s practical advice—“You need to get a job”—and his decision to join the army “still unable to find anything else.”

Military service leads to Kuwait and Iraq, where the book’s signature quiet—the elevators, buffets, chlorine glare of hotel pools—opens onto enormous moral weather. Days drag by “next to the pool” facing those Kuwait Towers “with a few blue spheres impaled on two of them,” and nights are scored by overlapping calls to prayer as he waits to be sent forward.

Combat leaves him with a medal and an unsharable reality: on the train home, cigarette smoke and reflected glass dissolve into the thought that “the things that left him feeling that nothing would ever be the same again… have no reality here.” He smokes more; he talks less. He becomes a man who has learned to separate sensations from explanations.

Back in England as a migrant, he runs security on the door of a strip club, the opposite of glamor: fifty hours a week “and still not having any money left at the end of the month,” no future beyond the next shift.

A chance meeting with a concierge-type operator, Mervyn—red trousers, Gucci loafers, big promises—pulls him into close protection work. You need an SIA license, Mervyn says; it’s “a formality.” It pays better. The modules cover physical intervention, conflict management, and fake-tactical pedagogy about anti-ambush and firearms (“Don’t try to be a hero”). He passes the multiple-choice tests and celebrates at Nando’s.

Through Mervyn he becomes a driver-bodyguard for the Nymans, a Cheyne Walk dynasty whose money is old enough to look casual. He watches their house parties from his roof windows and notices how the couple’s choreography changes when they are alone in the garden, laughing together, briefly human to his eye.

What begins as professional closeness with Helen Nyman escalates into an affair—hesitations, hotel rooms, a strange tower of privacy they build in plain sight of staff and guests. Their dialogue, at once banal and charged—“What am I here to do?” “Support me?”—captures the dependency that runs both ways: she uses him to feel alive; he uses her to feel chosen.

Meanwhile István experiments with other attachments—he sleeps with the family’s Canadian nanny, then shrugs off her morning-after regret; he keeps dating apps at arm’s length; he tells himself that no experience with a woman feels “entirely new,” a line of self-defense that also sounds like exhaustion.

In one of the loveliest set pieces, Helen takes him to an art gallery and Trafalgar Square for a cigarette; in one of the hardest, the affair’s friction expresses itself as questions about exclusivity, protection, and what either of them “wants.”

Time passes; consequences accrue. Helen becomes pregnant; their son, Jacob, grows up partly within István’s reach. The novel does not advertise the milestone; it simply starts using a new pronoun relationship—Jacob’s arms around “his father’s torso” on a quad bike—so quietly you can miss the shift. Fatherhood offers István flashes of “wordless purity” as he rides the estate tracks at speed, the lake flickering into view and out of it, but the idyll is fragile.

Power, which once felt like access to rooms and tables, turns around. The Nyman heir, Thomas—the very child whose nanny István once slept with—eventually inherits and sues. All the “loans that the trust fund had made to István’s projects” are declared against the terms of the trust; because the assets are worth less than the loans, lawyers “go after him personally.”

Bankruptcy follows. He and his mother leave England for the old town in Hungary and the small apartment that once contained their lives.

Middle age thins out into its own routines: he meets Bori, who works at a wine cellar, and they drift into a late-style companionship stitched with reserve. Her life carries its own secret ledger—she had a daughter at fifteen, put her up for adoption, reconnected decades later on Facebook; “Happy. And sad. I don’t know,” she says.

They walk together but don’t hold hands; he is pleased she doesn’t want to, because the lack of public display suits the new low-flame he can manage.

And then the last hinge turns. His mother dies “in her sleep,” a bare fact told without drama—the unspectacular way many lives end. The funeral is in May under chestnut flowers; petals scud on the asphalt in the wind and lie still when the wind drops. He returns to the apartment and, “after that he lives alone.”

How the ending works (and what it means): The novel closes not with a revelation but with an accounting: István declines a job (“I don’t know. It’s just not for me.”), buries his mother, and inhabits a quiet that the book has always, in some way, prepared us for.

The boy who learned to be wanted in a kitchen becomes the man who measures his bearings by rooms he doesn’t quite belong in—Kuwait hotel terraces, Cheyne Walk windows, the Munich suite where Helen asks vaguely for “support”—and by rooms that belong to him but that feel airless without the past’s noise.

If you map the novel’s incidents, you can see its spiral: the first staircase (the neighbor’s floor, the plants, the low window), the second staircase (the husband’s fall), the metaphorical staircases of class (service stairs in Cheyne Walk; the lift to a hotel terrace; a bridge over the North Circular).

Each step rehearses the same idea: bodies carry stories into rooms that don’t want them, but rooms rewrite those stories anyway. He is acquitted or at least freed after the interrogation (the text implies no conviction), but the doubt the detective plants—“You wanted him dead, didn’t you?”—never quite leaves him.

He is hired and desired by the rich, then made disposable by paperwork and inheritance. He is a father, but also a figure on the perimeter of his son’s life, thrilled by closeness and terrified of stability’s price.

Where some novels redeem their protagonists with a single clarifying choice, Flesh offers smaller tightenings: he refuses a promotion that doesn’t fit; he accepts Bori’s plain talk and plain limits; he tends to the daily disciplines of work and care inside a smaller map.

He does not win a courtroom battle or stage a reconciliation; he stops arguing with gravity. That quiet is the moral temperature of the last pages.

Scene-by-scene highlights that carry the plot:

- The grooming arc (Part I): the neighbor’s Somlói galuska, the first kiss, the escalation to oral sex and intercourse (with the shutter down), and the recurring use of “thank you.” The scenes are intensely literal and unsettlingly undramatic, which is the point: harm often sounds polite.

- The stairwell death and interrogation: his waiting on the steps; “I love you” / “No, you don’t”; the husband’s fall; the police car; the detective’s insinuations; and the survivor’s looping thought—did I mean it? did I not?—that the novel refuses to untie on his behalf.

- Army and Iraq: Kuwait’s blue-sphere skyline, the chlorine pool, the absence of alcohol, the medal on the fridge, the mother’s question, the son’s silence; the sense that war’s reality can’t pass customs at home.

- Mervyn and the SIA course: Romford modules, “don’t try to be a hero,” multiple-choice triumph, and the soft-power of class performance (“personal qualities”) required for “higher-end work.”

- Cheyne Walk and Helen: art galleries and airports; a lover whose question “Support me?” names everything and nothing; domestic spaces whose view he learns like a patrol route; the unseen but real arrival of Jacob into their lives.

- Bankruptcy and return: Thomas’s lawyers, the end of “projects,” repatriation to the mother’s flat, and the pared-down tenderness with Bori (who has her own adoption story, an echo that Flesh lets you hear).

- Coda—mother’s death: an ordinary morning, an empty room, chestnut petals at the cemetery, and the return to a quiet apartment. The last movement is not a crescendo but a true diminuendo.

Why a reader won’t need to “go back to the book” after this summary: the novel’s drama is not in plot twists (there are few) but in the accumulation of moral weight across very specific places and acts.

The neighbor’s kitchen and half-landing establish a grammar—gratitude, politeness, touch—that repeats in altered forms with Noémi, with soldiers in hotel lobbies, with Mervyn’s gatekeeping, with Helen’s soft instructions, with Jacob’s grip around his father’s ribs.

You’ve now seen the arc of those repetitions: how the first boundary-crossing becomes a template for later relationships; how a man can be both used and using, both wanted and displaced; how survival is sometimes a sequence of refusals (of jobs, of hands held) rather than a big speech.

Ending explained: István doesn’t die, confess, or “learn his lesson” in a way that cancels the past. He outlives the loudest consequences, loses the borrowed status of the Nyman years, and returns to the place where his earliest scripts were written. After his mother’s funeral, he chooses the smallness he can live inside.

Flesh ends with him alone—by choice as much as by fate—having finally stopped acting as if a new room will change the story. The last impression is steadiness rather than salvation: a man sized to his days.

If you want one sentence for the road: Flesh follows István from a teenage betrayal of trust through war, wealth, love, fatherhood, and bankruptcy, and leaves him in a quieter life that doesn’t fix what happened but no longer lies about it—proof that sometimes the truest ending is the one where nothing dramatic happens, and you carry on.

4. Flesh Analysis

4.1 Flesh Characters

István is written with a stubborn opacity that reads, to me, like trauma’s after-image: he feels most real when he says least.

As a teen he helps an older neighbor carry groceries; in the kitchen, after Somlói galuska, a small kiss becomes a pivot point—“her lips just lightly touch his for a moment.”

That lightness is the trap: the scene is ordinary, almost boring, which shows how harm can wear the mask of routine.

Later, as an adult back from Iraq, he can’t translate battlefield reality into domestic talk—“the things… that left him feeling that nothing would ever be the same again… have no reality here.”

He’s present in rooms but absent to himself, a condition Flesh observes without melodrama.

The neighbor emerges as a vexing portrait—neither caricature nor monster—whose tenderness (“You’re very strong”) sits beside predation, and whose apartment fills with sweets and silence.

Szalay’s refusal to flatten her into a single label is the point: systems fail when they need a simple story more than a true one.

Peripheral men—Ödön in the border wood, contractors in Kuwait, a friend named Norbi—outline a pipeline from petty illegality to globalized violence, the same gradient many European peripheries know too well.

The cast feels less like “supporting characters” than environmental pressures.

4.2 Flesh Themes and Symbolism

Consent and coercion.

Szalay stages harm not as a single blow but as incremental miscalibration: a kiss, a lesson, a habit of not speaking—“They don’t speak.”

Stairwells and half-landings recur as moral topography. When a confrontation ends with a fall—“he’s lying on the concrete floor of the half-landing, next to his wife’s plants”—the novel literalizes how ambiguity becomes catastrophe.

The police interrogation later presses that ambiguity into doubt: “he starts to wonder if he is remembering it right or not,” a line that echoes the way survivors internalize others’ versions of events.

Migration and money.

Kuwait’s blue-orb towers glint through a haze of vouchers and dry hotel buffets—capital’s promise feels both precise and empty. Flesh keeps showing how money purchases access—air-conditioned lobbies, private balconies—but not meaning.

The body as record.

Szalay has said he wanted to write “what it’s like to be a living body in the world,” and Flesh keeps faith with that project: smoke in the lungs, a navel piercing, hands on a rail, heat trapped under a stairwell window set “oddly low in the wall.”

5. Evaluation

1. Strengths / positive reading experience.

The prose is flint: scenes end a beat early, letting silence do the work, and the recurring motifs (stairs, glass, blue spheres) stitch years together without grand exposition.

Moments of world-detail—Somlói galuska, kovászos uborka on a balcony, Székely káposzta at a kitchen table—give the novel ethnographic specificity without turning characters into postcards.

Even the most charged scenes resist spectacle; the narrative trusts readers to add the moral voltage.

2. Weaknesses / what may frustrate.

Some will feel the emotional temperature is too low; István’s reticence can read as distance, and certain readers may crave the consolations of clear judgment.

There’s also deliberate ellipsis around legal process and later life outcomes; if you like dossiers, you’ll miss them here.

3. Impact (how it hit me).

I felt seen in Flesh’s admission that many adult decisions are re-enactments of early scripts; the text’s refusal to shout made the quiet devastations ring louder.

4. Comparison with similar works.

Imagine a bridge between Knausgård’s attentional realism and Tóibín’s moral hush, with shades of Szalay’s own Turbulence in its cross-border textures and of All That Man Is in its money-weather—yet Flesh feels more closely wound and ethically riskier.

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life: Similar: long tail of trauma shaping adult attachments; questions of care, power, and self-harm by omission. Different: Yanagihara is maximalist and operatic; Szalay is minimalist, anti-spectacle, and allergic to catharsis.

6. Personal Insight

When I taught consent and power dynamics in a media literacy seminar, students kept asking why “nothing happened” in some testimonies until years later, and Flesh is a master class in showing how “nothing” accrues into everything.

The biology “fitness” passage is a quiet grenade in this context: if success is measured by reproduction, how do cultural scripts about sex normalize harm by calling it adaptation?

Pair the novel with current research on trauma’s long-tail effects on risk-taking and addictive behaviors in young adults, or with reporting on how grooming blurs agency, and you get a syllabus that lets students map story to stats.

For cross-reading, I’d assign the AP review for a concise critical baseline, the Booker interview for authorial intent, and one longform essay situating Flesh within masculinity studies.

Finally, for global-literature modules, use Flesh alongside migration-era fiction and reportage, then ask students to annotate “threshold” spaces (stairs, borders, hotel lobbies) across texts and news articles; the exercise reliably surfaces how architecture encodes power.

7. Flesh Quotes

- “They don’t speak.”

- “You’re very strong,” she says to him as he puts the heavy stuff down on her kitchen table.

- “Can I kiss you?” … It’s nothing—“her lips just lightly touch his for a moment.”

- “Modern evolutionary theory defines fitness not by how long an organism lives, but by how successful it is at reproducing.”

- “The window is set oddly low in the wall. In fact it extends below the level of the floor.”

- “Thank you,” she says … “After that they kiss every time.”

- “Have you ever kissed anyone properly? … He shuts his eyes so that he doesn’t have to see her.”

- “It’s not okay, he thinks… She disgusts him.”

- “I love you,” he says. “No, you don’t.”

- “There’s a strange loud sound as his head hits [the handrail]… then he’s lying on the concrete floor of the half-landing, next to his wife’s plants.”

- “What did he do? Steal a liter of milk?” … “No, he killed someone.”

- “He starts to wonder if he is remembering it right or not.”

- “It’s hard to say what his intention was… when he pushed the man and he fell down the stairs… and didn’t get up.”

- “Those three towers that look like spikes pointing at the sky, with a few blue spheres impaled on two of them.”

- “In the evening there’s the sound of the mosques… overlapping, so that the overall effect is slightly chaotic.”

- “If you’re near it… an explosion isn’t just sound. It’s pressure as well… You experience it as pressure, not as sound.”

- “How often do you think about what happened?” — “Every day.” — “Every day?” — “Yeah… Literally.”

- “The things that left him feeling that nothing would ever be the same again… just aren’t important here. Those things have no reality here.”

- “She leans down… says that he’s a man now… He thinks it’s strange that he doesn’t feel any different.”

- “The window is open… The lace curtains move slightly in the draft from the open window.”

8. Conclusion

Szalay’s Flesh is not a courtroom, a sermon, or a thriller; it’s a ledger where youth’s smallest debits compound into adulthood’s balance sheet, and the math never quite clears.

I recommend it to readers who value quiet intensity: fans of contemporary European realism, of books longlisted and shortlisted for major prizes, and of novels that examine sex, money, and migration not as headlines but as atmospheres.

In a data-hungry world, Flesh reminds us that the most decisive variables are often the ones we don’t measure: a stairwell turn, a sentence unsaid, a touch that shouldn’t have been asked for at all.

Read also