Renting a spare room should solve a cash-flow problem—not ignite a psychological war at home. The Tenant solves that problem by showing how a “simple” housing fix can become the most dangerous decision of your life.

Freida McFadden turns a brownstone share into a pressure cooker where a couple, a too-perfect renter, and a pile of secrets collide in a twisty psychological thriller about trust, control, and revenge.

McFadden’s opening stakes are immediate—“Six months ago, someone stood in this exact spot… and tried to jump,” the new VP narrator recalls, before admitting, “And now I’ve got his job,” grounding the corporate and moral tension that will spill into home life.

Later, a staged “psychic” warns, “He’s going to kill you, Krista,” a manipulation that ricochets through the plot.

Publication details confirm its 2025 release through Poisoned Pen Press, with ISBNs and formats listed on the author’s official site and retailer pages.

The Tenant is Best for readers who love psychological thriller tension, domestic noir, and gasp-out-loud reversals—especially fans of The Housemaid. Not for readers who want graphic violence or explicit content; McFadden notes she keeps her thrillers “family-friendly.”

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

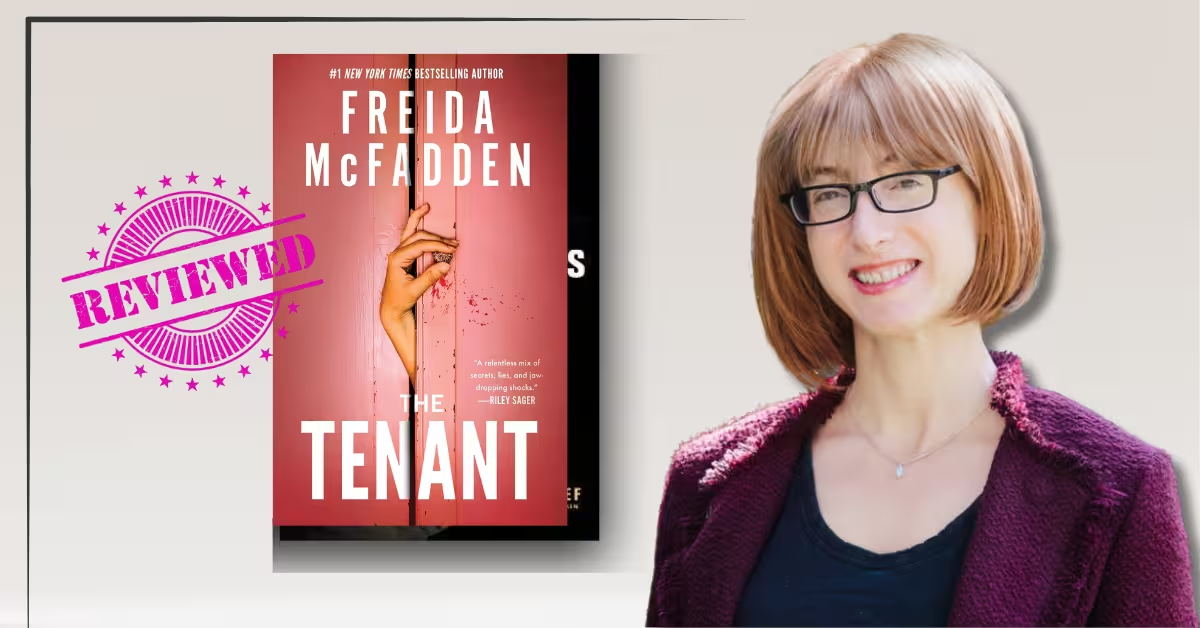

The Tenant (2025) is a psychological thriller by #1 New York Times–bestselling author and practicing physician Freida McFadden, published by Poisoned Pen Press (Sourcebooks).

McFadden—known for The Housemaid—writes with a clinician’s precision and a page-turner’s pacing, part of why her work has become a multi-list bestseller.

From the first page, The Tenant positions a work crisis (“someone…tried to jump”) alongside new power (the narrator inherits the job), then shifts home—where one “perfect” tenant becomes a wedge.

2. Background

McFadden’s author’s note signals her tonal lane: dark topics, yes, but without graphic extremes—useful context for educators or readers sensitive to explicit content.

Historically, the “tenant thriller” sits within domestic noir—Ruth Ware, Shari Lapena, and Greer Hendricks/Sarah Pekkanen have explored similar home-as-battleground setups—yet McFadden’s trademark is brisk escalation and twist engineering, sharpened by her medical background.

The 2025 publication places The Tenant alongside a wave of housing-anxiety fiction (post-pandemic relocations, rent spikes), making its brownstone rent-out premise feel viscerally contemporary rather than contrived.

3. The Tenant Summary

Blake Porter is riding high as the freshly minted VP of marketing at Coble & Roy when the novel opens: the previous VP had a breakdown and tried to jump from their twenty-fifth-floor office—and Blake got the corner chair and the nameplate to match.

He’s also newly engaged to Krista Marshall, his steady, cinnamon-cookie-baking partner in their Upper West Side brownstone. But Blake’s ascent is short-lived. Summoned by his boss Wayne, he’s abruptly accused of selling proprietary files to a competitor and fired on the spot, with threats of prosecution and no severance. “Get. Out,” Wayne says, calling security as the office watches.

Unemployment cracks Blake’s confidence and his relationship. The mortgage is brutal; the brownstone feels like a financial noose; and Krista—practical, supportive, quietly determined—presses a solution Blake hates: take in a tenant. He relents, and they start interviewing. One prospect jokes about eating their goldfish, Goldy (“beer battered” gets a laugh), but most candidates are walking red flags.

Then comes a woman who seems almost too perfect: Whitney Cross, a polite server from Cosmo’s Diner who gushes over homemade cookies, coos at Goldy, and calls a dishwasher “heavenly.” Blake is uneasy, but the background check he pays for shows “no red flags at all”—no arrests, no warrants, decent credit. The money is needed, so they offer her the room.

Trouble begins as soon as Whitney moves in. Blake, already insecure about his job loss and image, reads every small friction as an insult or conspiracy: missing cereal, a too-comfortable tone with Krista, innocent borrowing. He insists on “due diligence” like a mantra—social security number, reference checks—while confessing a nagging voice says to “get rid of her right now.”

To complicate things, a bizarre “psychic” shows up during another viewing and proclaims, in front of Blake, that he will “stab [Krista] with a kitchen knife…right here.” The woman, calling herself Quillizabeth, is so melodramatic that even Krista treats it as campy performance—until she’s outside and the woman clutches her arm, insisting the vision was real. The moment plants a seed of dread.

Domestic micro-wars escalate. Goldy the goldfish dies under suspicious circumstances, and Whitney’s consoling eulogy infuriates Blake—he’s convinced Whitney killed the fish with bleach, and his outburst only alienates Krista further. Whitney looks like a saint; Blake looks unhinged.

Then Blake’s behavior does get unhinged. He discovers a rotten fruit bag teeming with maggots (we later learn it’s part of a larger scheme) and, in a vengeful spasm, tosses maggoty apples on Whitney’s bed. Moments later, Krista finds Whitney sobbing over the mess—proof, it seems, that Blake has become dangerous. “He’s horrible,” Whitney cries; Krista, rattled, begins to wonder if the psychic might be right.

Blake spirals—no job, a tenant he mistrusts, a fiancée who keeps retreating to her best friend Becky’s place—and his paranoia shifts into detective work. He goes “deeper” on Whitney online and finds almost nothing—“not one digital footprint”—which only hardens his suspicions. Meanwhile, dinners with Becky and Malcolm (a coworker from Coble & Roy) humiliate him; even his skin breaks out in rashes that he can’t explain.

The mid-book turn: who’s playing whom?

Halfway through, The Tenant flips perspective and stakes. We learn the “psychic” was a plant, the awful interviewees were actors, and the cascade of “coincidences” weren’t coincidences at all.

The mastermind isn’t Whitney. It’s Krista. With the quiet help of a tech-savvy acquaintance named Elijah, Krista has been systematically destroying Blake’s career, sanity, and credibility—ever since she discovered he’d “slipped” with his secretary Stacie. First, she copied Blake’s client files to a flash drive and sold them to a competitor, ensuring Wayne would fire him and trash his reputation. Then she stacked the tenant pool with performers to push Whitney to the top of the list.

Why target Whitney? Because “Whitney Cross” isn’t who she says she is—she’s Amanda Lenhart, a former biology PhD who bought a new identity after borrowing from dangerous lenders to pay for her mother’s cancer treatment. Amanda confesses this to Krista in a private, teary scene—“not the kind of thing where you can go to a bank and get a loan for chemotherapy,” she explains—believing Krista will keep her secret. Krista smiles and nods…then decides both Blake and Amanda “deserve to be punished.”

In a further jolt, Krista reveals a deeper obsession: she is, in fact, the original Whitney Cross—the one whose identity Amanda “stole.” “I wasn’t murdered,” Krista scoffs internally. “I simply wasn’t using my identity for a little while.”

The theft is, to Krista, the supreme violation. Her “solution” is simple, chilling, and entirely in character: once Amanda is dead, she can “take my name back.”

From here, the novel reframes everything we’ve seen. The rash tormenting Blake? Krista quietly spiked his hypoallergenic laundry detergent with limonene, knowing he’s allergic. The rotting fruit infestation? She engineered Blake’s freak-out by planting decay in the house. The “knife” prophecy? Stagecraft designed to pre-author a future crime scene. She wants to isolate Blake, goad Whitney/Amanda into vulnerability, and orchestrate a murder in the living room that will look exactly like the psychic’s “vision.”

And one more shoe drops: Krista isn’t merely vengeful—she’s a serial killer. The press will later tally “all the dead bodies left in her wake,” not just Stacie (Blake’s secretary) and a neighbor named Mr. Zimmerly, but more, stretching back years. By the time Blake fully grasps who he’s engaged to, it’s nearly too late.

The long night: poison, prophecy, and the living room

Having weaponized rumor, rashes, and fear, Krista escalates to murder. She bakes one of her trademark cookie batches—but this time laces them with tetrodotoxin (the famed pufferfish neurotoxin). Blake eats, stumbles into the night in a slow-motion suffocation, and barely manages to ring the doorbell—“I need help,” he thinks, as the world tilts.

Inside, Krista has Whitney/Amanda on the sofa scrolling apartment listings—killing time while waiting for the “scene” to begin. She taunts Amanda about the stolen name, prods her about identity choices, and paces the living room littered with just enough of Blake’s mail to claim he’d “snapped.” Her aim is to fulfill Quillizabeth’s prophecy to the letter: a kitchen-knife death “right here.”

But when Blake collapses in the foyer, blue-lipped and barely breathing, the tableau fractures. A struggle follows—brief, vicious. Krista lunges to finish Blake while he’s helpless; Whitney/Amanda intervenes from behind with a knife; 911 is called. The scene lands in three awful lines: “I love you,” Blake tells Krista as she bleeds; a “bubble of blood” forms on her lips; her body goes still. The last words in her POV are bitter: “I knew I should have stabbed Amanda one more time.”

Blake survives the tetrodotoxin—“there’s no antidote,” the doctor says, but if you live through the first day, you have a shot—and wakes to the post-mortem: the media splashes stories on Krista’s (real name: Whitney Cross’s) body count, and investigators begin tying threads from Stacie to Mr. Zimmerly to the “psychic” ruse to the sabotage at Coble & Roy. “Krista was a psychopath,” Blake says in the grim lull afterward, then admits he still misses her. It’s messy, human, and very McFadden.

The aftershocks: identities, jobs, and one last choice

In the hospital’s hum, Blake’s life is rewritten again. With the truth exposed, Wayne offers him the VP job back; Blake refuses. He’s done. The New York grind, the office that once intoxicated him, and the nameplate he threw at the wall now feel poisoned. He decides to go home to Cleveland and take over his father’s hardware store, choosing a smaller, saner life. In the epilogue, he packs the car, says goodbye to the city, and means it.

And Whitney/Amanda? She’s wounded but alive. She saved Blake’s life, and they share a complicated tenderness in the days after—at one point they even sleep together, which both of them regret and then quietly shelf. Blake invites her to stay in the brownstone; he retracts the angry eviction order. She considers it; for now, a decent mattress beats a lumpy couch. She also hints she’s “worked something out” about her identity exposure in the media wake of Krista’s crimes.

The book leaves her path open, but her confession about the stolen name has already reframed her: not a femme fatale, but a survivor whose worst act (identity theft) was a desperate shield against violence and debt after trying to save her mother.

How all the puzzle pieces lock

What makes The Tenant click is how McFadden reverses the presumed vectors of danger. From Blake’s first page—“And now I’ve got his job”—we’re primed to read him as a brittle, maybe toxic narrator who could become violent; the psychic scene crystallizes that dread as a predictive image.

Yet the real engine is Krista, who weaponizes domestic normalcy—cookies, laundry detergent, apartment tours, even a goldfish funeral—into a meticulous campaign of isolation and believability. She understands that in an intimate triangle, optics are everything. If Blake appears unbalanced (rashes, outbursts, maggots), and Whitney appears gentle (tears, careful sympathy, cash for rent), then the final “prophecy come true” will require no straining of the audience’s imagination. She almost gets her perfect ending.

The twist that Krista is the original Whitney Cross adds a nasty, elegant loop: the “tenant” didn’t invade Krista’s home; Krista believes the tenant invaded her self. It retrofits every earlier beat—her fixation on Whitney’s politeness, the time-buying apartment search, the hostility at any hint that Amanda might like Blake—into a single motive: reclaim the name, reclaim the narrative, erase the witness. “Once Whitney/Amanda is dead, I can take my name back,” she thinks, the cruelty tucked in a matter-of-fact future tense.

Finally, the ending earns the psychic’s prophecy by subverting it: a stabbing does happen in the living room, but not the one foretold. Amanda’s knife prevents murder, not commits it. Blake is saved; Krista dies; the vision turns out to be theater after all—even as the apartment floor is, indeed, “all over” with blood.

Ending Explained

- Who is the villain? Krista (whose real identity is Whitney Cross). She’s a serial killer who has long “solved” problems by eliminating people—Stacie, Mr. Zimmerly, and more (as later reported by the press).

- What was her plan? Ruin Blake’s career (selling his files), isolate him socially, seed the house with staged events (maggots, “psychic”) to establish an unhinged pattern, then poison him with tetrodotoxin so he can’t fight back. She meant to fulfill the “vision”: Blake stabs Krista—except the real thrust was that Krista would make it look that way after killing Amanda and letting Blake die.

- What about Whitney? “Whitney” is Amanda Lenhart, who bought the identity after borrowing from criminal lenders to pay for her mother’s chemo; her mother died anyway. She isn’t faultless, but she isn’t the predator Blake feared. When the moment comes, she stabs Krista from behind to stop her—saving Blake’s life and calling 911.

- Does Blake survive? Yes. There’s no antidote to tetrodotoxin, but survival odds improve after 24 hours; he pulls through and later rejects his old job to take over his father’s hardware store in Cleveland.

- What’s the final status of Amanda? She recovers, contemplates staying in the brownstone, hints she has handled the identity issue created by the news coverage, and shares a bittersweet, bounded closeness with Blake. The novel ends with Blake leaving New York for good.

Too long, didn’t read?

A laid-off VP (Blake) and his fiancée (Krista) rent a room to a sweet server named “Whitney Cross” who has no digital footprint and perfect manners. Blake suspects Whitney; a “psychic” foretells a living-room stabbing; the goldfish dies; maggots appear; and Blake seems to unravel.

Midway, the book flips: Whitney is actually Amanda, a former PhD who bought a new identity to escape lenders; the real danger is Krista, the original Whitney Cross, a practiced killer who sabotaged Blake’s job, staged the psychic’s warning, and plans to murder Amanda and let Blake die after poisoning him with tetrodotoxin—all to reclaim her name and erase witnesses.

In the climactic scene, Amanda stabs Krista from behind to save Blake; Blake survives; the press exposes Krista’s killings; Blake rejects his old life and leaves New York, while Amanda navigates her future with her complicated secret in the open.

4. The Tenant Analysis

4.1 The Tenant Characters

Blake Porter (our initial narrator) embodies competence curdling into paranoia—he’s freshly promoted after another man’s breakdown (“And now I’ve got his job”), a detail that loads every later insecurity.

Krista, his fiancée, is practical until fear (and manipulation) nibbles at her resolve, especially after a “psychic” theatrically insists, “He’s going to stab you with a kitchen knife…right here.”

Enter Whitney Cross, the tenant whose background check shows “no red flags at all,” yet whose too-eager charm (“Very interested”) and missing furniture hint at deeper design.

Between them, McFadden threads ambiguity: Blake’s unreliability (jealous, controlling, newly unemployed), Krista’s susceptibility to staged “omens,” and Whitney’s strategic innocence (“I don’t have any of my own stuff”).

A memorable running bit—the beloved fish Goldy—becomes an emblem of domestic stakes; when Goldy dies, Blake’s rage (“I wish I could bury her in the ground”) exposes how thin the household peace really is.

4.2 The Tenant Themes and Symbolism

Trust vs. Control.

Routine “due diligence” (“Social Security number…credit check…reference”) reads as smart adulting—until it doesn’t protect against what really matters: motive.

Performance and Belief.

The “psychic” episode literalizes the novel’s obsession with performance—Krista initially treats it as theater, then shivers when belief creeps in: “I get a chill down my spine.”

Home as Battleground.

The brownstone tour—dishwasher envy, laundry relief, closet inventory—reads cozy, then curdles; McFadden turns every domestic convenience into a surveillance point and power node.

Identity and Reinvention.

Online footprints (or their absence) become plot levers: Blake’s “deeper dive” finds “not one digital footprint,” amplifying paranoia and the theme of curated selves.

5. Evaluation

1) Strengths (pleasant/positive).

McFadden’s pacing is propulsive: short scenes, cliffy beats, and textured domestic details.

She seeds red flags early—“Why does this voice…keep telling me to get rid of her right now?”—so reveals feel earned.

Dialogue is slyly funny (the goldfish-eating applicant; “beer battered”), humanizing characters before the screws turn.

2) Weaknesses (negative experiences).

Some readers may find the psychic set-piece on-the-nose, even if meta-thematically apt; it loudly telegraphs a murder tableau that the book then toys with. Occasionally, coincidence stacks high (job loss, tenant timing, secrets), and one late-game turn requires generous suspension of disbelief—par for the psychological thriller course but worth noting.

3) Impact (my resonance).

Because the home is the battlefield, small gestures—cookies, laundry, a shared sofa—sting; I came away aware of how easily logistics mask leverage. Also, the book’s restraint (no graphic scenes) paradoxically makes the dread feel closer to real life.

4) Comparison with Similar Works.

Readers who devour The Housemaid (film adaptation underway) will feel at home with McFadden’s psychological gears—secrets, class friction, unreliable intimacy—even as The Tenant stays self-contained.

5) Adaptation.

As of now, no TV or film adaptation of The Tenant has been announced; most media focus is on The Housemaid’s forthcoming film. If it were adapted, the book’s compact set (the brownstone) begs for a limited-series treatment, leaning into visual motifs—the tilted office window, the kitchen knife, the goldfish bowl.

6. Personal Insight

Landlord-tenant relationships are spiking in pop culture because the economics are spiking in life: post-pandemic rent increases, roommate dependence, and credit-check gatekeeping define urban survival. The Tenant uses those mundane levers (“credit check…reference”) as plot keys, making it an excellent anchor text for media-literacy or sociology modules on power in domestic arrangements.

For further reading on adaptation culture and how source material morphs on screen (helpful when discussing McFadden’s broader franchise presence), see this analysis of another canon text’s film shift, which models how to map book-to-screen changes.

In classroom settings, pair The Tenant with news on the Housemaid film to explore why some narratives jump mediums faster—star packages, fan communities, and social media momentum.

7. Conclusion

On balance, The Tenant is a tightly wound, domestically scaled psychological thriller that turns rent, rooms, and routines into weapons—very Freida McFadden, very now.

Recommended for fans of psychological thrillers, domestic noir, and readers who prefer dread to gore; less ideal for those seeking literary stylization over high-concept suspense.

Its significance lies in how it captures the economics of intimacy—the way financial strain (a mortgage, a room to let) can invite a stranger into your plot and make your home your most dangerous setting.

Final take

If your search history is full of “best psychological thriller 2025,” “Freida McFadden new book,” or “tenant book review,” The Tenant is your next one-sitting read.

And if you’re contemplating renting out a room to ease your mortgage, consider this your cautionary tale—because, as McFadden reminds us, the most dangerous secrets often sign a lease and move in.