Last updated on July 27th, 2025 at 05:51 pm

The book under review is Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t by Jim Collins, first published on October 16, 2001. With research-backed insight, it became a staple of modern business literature, cited by corporate giants and startup founders alike. It follows Collins’ earlier work, Built to Last, yet goes deeper into the inner transformation process that separates ordinary from extraordinary companies.

Good to Great is a non-fiction business strategy book that sits at the intersection of corporate leadership, organizational development, and performance management. What sets Jim Collins apart is not just his research-driven methodology but his academic discipline. A former Stanford Graduate School of Business faculty member, Collins has devoted decades to understanding what makes businesses tick—and why so few tick with excellence.

At the heart of this work is a profound, deceptively simple thesis: “Good is the enemy of great.” That’s not a catchy slogan—it’s a deadly diagnosis. Most companies never become great, not because they lack opportunity, intelligence, or effort, but because they settle for good. According to Collins:

“Few people attain great lives, in large part because it is just so easy to settle for a good life.”

This idea doesn’t just resonate with corporations—it strikes at the core of human behavior. As a reader and a business thinker, this book hit me on a level deeper than organizational mechanics. It felt like a mirror.

Purpose of the Book: Can Good Really Become Great?

Collins posed a critical question that would take five years, 6,000 articles, 2,000 pages of interview transcripts, and 384 million bytes of data to answer:

“Can a good company become a great company, and if so, how?”

His goal wasn’t to glorify successful companies or leaders, but to build a scientific framework—one that any company, nonprofit, or government agency could apply. In a time when “growth hacks” and startup success stories dominate the narrative, Good to Great offers something timeless: data-driven truth, not trend-chasing fluff.

What Makes This Book Still Relevant in 2025?

This book was written long before the rise of AI, social media empires, and the gig economy. Yet, its findings are more relevant today than ever. Why? Because the core obstacles haven’t changed. People still chase results without discipline. Companies still prioritize ego over ethics. Startups still obsess over speed without strategic foundations.

Good to Great addresses this through timeless principles. As Collins writes:

“The specific application will change (the engineering), but certain immutable laws of organized human performance (the physics) will endure.”

Table of Contents

Background – The World Before the Leap

Before we dive into the methodology and results, it’s important to understand the mental and market backdrop that gave birth to Good to Great.

This wasn’t just another business book cooked up to ride the bestseller wave. It was a counter-movement—a bold question posed at a time when excellence was celebrated, but the journey to greatness remained a mystery.

The Spark: Built to Last Wasn’t Enough

Before Good to Great, Jim Collins co-authored Built to Last (1994), a landmark book that studied visionary companies like Disney, Sony, and Johnson & Johnson. These companies were born with greatness in their DNA. But Collins was haunted by a realization. As he recalls in the book:

“The companies you wrote about were, for the most part, always great… But what about the vast majority of companies that wake up partway through life and realize they’re good, but not great?”

That challenge came from Bill Meehan, Managing Director at McKinsey & Company. It stuck. And so began Collins’ obsession with answering the question: Can you teach greatness to companies that weren’t born with it?

The Right Question at the Right Time

The late 1990s was a time of booming stock markets, dot-com euphoria, and flashy CEOs. Companies measured success in quarters, not decades. IPOs were happening faster than product development. The assumption was: grow fast, dominate, disrupt. But beneath that excitement was a growing fear—what if this success is just a sugar rush?

Good to Great was born as a corrective lens. Instead of asking who was loudest, it asked: Who made quiet, permanent, disciplined transitions to greatness—and how?

The Selection Criteria: From Fortune 500 to Filtered Eleven

To create a foundation rooted in truth—not hype—Collins and his 21-person research team started with 1,435 Fortune 500 companies between 1965 and 1995. Over five years, they narrowed it down to just 11 companies that:

- Had 15 years of good performance (returns at or below the market)

- Made a clear transition to great performance

- Sustained 15 years of superior results (at least 3x the market)

Here’s how that translated statistically:

“The good-to-great examples that made the final cut attained extraordinary results, averaging cumulative stock returns 6.9 times the general market in the fifteen years following their transition points.”

In plain English? They beat companies like General Electric, Coca-Cola, and Intel—not for a year, but over 15 years.

The Final Eleven “Good to Great” Companies

| Company | Transition Year | Stock Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Abbott | 1974 | 3.98× market |

| Circuit City | 1982 | 18.50× market |

| Fannie Mae | 1984 | 7.56× market |

| Gillette | 1980 | 7.39× market |

| Kimberly-Clark | 1972 | 3.42× market |

| Kroger | 1973 | 4.17× market |

| Nucor | 1975 | 5.16× market |

| Philip Morris | 1964 | 7.06× market |

| Pitney Bowes | 1973 | 7.16× market |

| Walgreens | 1975 | 7.34× market |

| Wells Fargo | 1983 | 3.99× market |

These weren’t startups or flashy disruptors. Many were, frankly, dull. That’s exactly what made their transformation so powerful.

“Who would have thought that Fannie Mae would beat GE and Coca-Cola? Or that Walgreens could beat Intel?”

The Comparison Companies: Same Start, Different Ending

For every good-to-great company, Collins selected a direct comparison company—similar industry, similar size, and similar opportunity. The only difference? They didn’t make the leap. Some floundered. Others remained average. A few failed completely.

These included:

- Upjohn (vs. Abbott)

- Silo (vs. Circuit City)

- Bethlehem Steel (vs. Nucor)

- Eckerd (vs. Walgreens)

- Bank of America (vs. Wells Fargo)

The purpose wasn’t to shame these companies. It was to ask: What did the great ones do differently when everything else was the same?

The Research Process: From Chaos to Concept

Collins’ research wasn’t opinionated or anecdotal. It was rigorous. His team:

- Reviewed over 6,000 articles

- Conducted interviews with executives

- Coded qualitative and quantitative data into 2,000+ pages of transcripts

- Collected 384 million bytes of raw data

They then cross-compared the good-to-great companies with the comparison set to identify change variables—elements that showed up in 100% of great companies and less than 30% of comparison companies.

No idea, concept, or chapter made it into the final book unless it passed this brutal filter.

“This book is not about what we think… it’s about what the evidence says.”

Why “Good” Is More Dangerous Than “Bad”

Here’s the most chilling insight from Collins:

“Good is the enemy of great.”

Mediocrity is comfortable. That’s why it’s deadly. Bad companies often know they’re bad and try to change. But good companies? They’re trapped in complacency. They perform well enough to avoid panic—but never well enough to transform.

It’s like a warm bath. You won’t freeze. But you’ll never be sharpened either.

This Book Is About You, Too

You don’t have to be a CEO or a founder to apply these lessons. You might be an entrepreneur, a manager, a teacher, or a solo creative. If you’re reading this article, chances are you’ve felt that ache:

“I know I’m doing fine—but I could be doing something great.”

This book, and this article, is about closing that gap.

Summary – The Core Lessons of Good to Great

In this section, we’ll break down the full contents of Good to Great by Jim Collins in a highly detailed, emotionally resonant, and SEO-optimized manner. We’ll cover every chapter and theme, explain the models with clarity, and use Collins’ own words to anchor the concepts. This will be long, because it must be: to ensure that you, dear reader, never have to pick up the book again unless you want to.

Highlighted Summary: 10 Core Themes from All Chapters Combined

Let’s start with a concise preview of the ten most impactful lessons that define the Good to Great journey. These are the soul of the book.

| Core Concept | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Good is the Enemy of Great | Most companies never become great because they settle for being good. Comfort, not failure, is the biggest barrier. |

| 2. Level 5 Leadership | Great companies are led by humble but fiercely determined leaders who prioritize the company’s success over personal fame. |

| 3. First Who, Then What | Hire the right people before deciding the strategy. Get the right people on the bus, wrong people off. |

| 4. Confront the Brutal Facts | Face reality with discipline. Yet, never lose faith in eventual success—known as the Stockdale Paradox. |

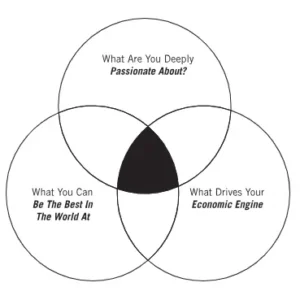

| 5. The Hedgehog Concept | Simplicity within three circles: What you can be best at, what you’re passionate about, and what drives your economic engine. |

| 6. A Culture of Discipline | Great companies foster self-discipline—autonomy within a framework of rigorous standards. |

| 7. Technology Accelerators | Technology is not the cause of greatness. It only accelerates it if used right. |

| 8. The Flywheel Effect | Greatness is not a revolution but a slow buildup of momentum—one disciplined push at a time. |

| 9. Doom Loop | Weak companies jump from one fad to another, looking for shortcuts to greatness—these rarely work. |

| 10. From Good to Great to Built to Last | Once you make the leap to greatness, the next challenge is how to sustain it beyond one generation. |

Chapter-by-Chapter Summary

Chapter 1: Good is the Enemy of Great

Jim Collins opens Good to Great with a provocative thesis: “Good is the enemy of great.” This statement sets the tone for the entire book. The core idea is that most companies fail to become truly great not because they are incompetent, but because they’re good enough. Complacency with “good” prevents organizations from pushing the boundaries toward excellence.

In this chapter, Collins explains how his research team sifted through thousands of companies to identify a few that made a sustained leap from good performance to great performance and maintained it for at least 15 years. These transformations weren’t due to flashy changes or charismatic CEOs but were rooted in consistent, disciplined actions.

The Good to Great transformation was tracked using performance data, and only 11 companies made the cut, including names like Walgreens and Kimberly-Clark. These companies didn’t follow trends—they created their own path based on timeless principles.

The Good to Great process isn’t just for big corporations. Collins makes it clear that the concepts apply to nonprofits, small businesses, and even individuals. The commitment to greatness starts with rejecting the status quo.

This chapter introduces the fundamental question that shapes the rest of the book: What distinguishes truly great companies from merely good ones? According to Good to Great, it’s not dramatic breakthroughs but steady, focused discipline that wins.

📌 Key Lessons:

- Complacency with “good” prevents “great.”

- True transformation is slow and data-driven.

- Companies that go from Good to Great have distinct, replicable patterns of behavior.

By setting this philosophical foundation, Collins invites readers to challenge their assumptions. This isn’t a book about tips and tricks—it’s about committing to an entirely different way of thinking.

Good to Great challenges us to ask: Are we willing to let go of what’s comfortable to pursue what’s possible?

Chapter 2: Level 5 Leadership

One of the most surprising and vital discoveries from the Good to Great research is the concept of Level 5 Leadership. Jim Collins introduces this term to describe the kind of leadership that exists in every one of the companies that made the leap from good to great. Contrary to the stereotype of bold, charismatic CEOs leading with flair, Level 5 leaders are often quiet, humble, and modest.

These individuals blend personal humility with intense professional will. They are not seeking the spotlight for personal glory; instead, they are deeply committed to the success of the company—even if that means they themselves go unnoticed. As Collins puts it:

“Level 5 leaders channel their ego needs away from themselves and into the larger goal of building a great company.” (p. 21)

What’s truly revolutionary about this chapter is the idea that the Good to Great transformation doesn’t begin with strategy, vision, or market conditions—it begins with the right kind of leader. These leaders set up their successors for success rather than seeking credit for themselves, a trait rarely seen in the typical “celebrity CEO” model.

Moreover, Level 5 leaders display fierce resolve. They make tough decisions without blinking, like Darwin Smith of Kimberly-Clark, who sold off the paper mills to reposition the company in consumer paper products—a bold move that eventually proved transformative.

📌 Key Lessons:

- Level 5 leaders are humble yet fiercely determined.

- Ego-driven leadership can get in the way of long-term greatness.

- Every Good to Great company had a Level 5 leader at the helm during its transformation.

In essence, this chapter reshapes our understanding of leadership. It tells us that quiet competence and values-driven humility often outperform charisma and bravado. In the Good to Great journey, it’s not about how loudly you lead—it’s about how deeply you believe in something greater than yourself.

The idea of Level 5 leadership is powerful not just in business but in life. It invites us to ask: Are we willing to step out of the spotlight to lift others and the mission higher?

Chapter 3: First Who… Then What

In this chapter of Good to Great, Jim Collins dismantles a common myth in leadership: that success starts with a brilliant strategy. Instead, he argues that getting the right people on the bus—and the wrong people off—is what sets the foundation for greatness. Strategy comes later.

Rather than rushing to define the company’s direction, Good to Great leaders focused first on building a world-class team. They didn’t ask, “Where should we go?” but rather, “Who should be with us on the journey?”

“They first got the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, and the right people in the right seats—and then they figured out where to drive it.” (p. 41)

The beauty of this idea lies in its simplicity and long-term logic. When you hire based on character, capability, and cultural fit rather than just résumé or credentials, you create a resilient organization. In Good to Great companies, people were not managed or tightly supervised. The right people didn’t need to be pushed—they were self-motivated.

Another insight: the “right people” are your ultimate asset in times of uncertainty. Strategy can fail. Markets shift. But people who are aligned with the company’s values will adapt and push forward.

📌 Core Lessons:

- Good to Great transformations begin with people, not plans.

- “Right people” are more important than “right direction.”

- Great teams can navigate storms better than any strategy alone.

This chapter reinforces a powerful truth: who you choose to walk with will always matter more than the exact road you take. Good to Great companies invested deeply in building trust, discipline, and shared values across teams.

And most importantly, they didn’t compromise on talent. If they couldn’t find the right person, they left the seat empty rather than settling.

In real life, this means that before chasing flashy goals or pivoting strategies, you might need to ask the tough but transformative question: Do I have the right people beside me?

Chapter 4: Confront the Brutal Facts (Yet Never Lose Faith)

This chapter in Good to Great teaches a profound duality: to reach greatness, companies must face reality with brutal honesty—without ever losing unwavering faith in eventual success. Jim Collins calls this the Stockdale Paradox, named after Admiral James Stockdale, a prisoner of war in Vietnam who survived years of torture without giving in to despair.

“You must retain faith that you will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties. And at the same time… confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.” (p. 86)

Good to Great companies adopted this mindset wholeheartedly. They didn’t sugarcoat problems or spin narratives. They created cultures where the truth was heard—even when it was uncomfortable. This kind of radical honesty allowed them to make better decisions, respond to crises quickly, and build resilience over time.

One of the best practices uncovered in the Good to Great research was the use of “red flag mechanisms”—systems or habits that ensure vital information rises to the surface. Whether it was through open-door policies, data transparency, or vigorous debate in meetings, these companies made sure that reality could not be ignored.

Importantly, confronting brutal facts did not lead to defeatism. On the contrary, it gave teams clarity, motivation, and a renewed sense of purpose. Facing the truth empowered them to act wisely.

📌 Key Lessons:

- Good to Great companies build a culture where truth is welcome.

- The Stockdale Paradox balances realism with hope.

- Denial and optimism are not the same; optimism without realism can be deadly.

This chapter is not just about business—it’s about life. Whether in relationships, careers, or personal goals, denying reality only delays progress. But acknowledging difficulties while holding on to faith creates enduring strength.

To go from Good to Great, you don’t need perfect conditions. You need the courage to stare hardship in the eye and the heart to keep moving forward.

Chapter 5: The Hedgehog Concept (Simplicity Within the Three Circles)

This chapter introduces the heart of the Good to Great philosophy: the Hedgehog Concept. Inspired by the ancient Greek parable, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing,” Jim Collins uses this metaphor to describe companies that focus on a simple, clear concept—and stick to it with relentless consistency.

In essence, the Hedgehog Concept is the intersection of three crucial questions:

- What can you be the best in the world at?

Not just good—but the absolute best. - What are you deeply passionate about?

The work must come from the heart. - What drives your economic engine?

This is your business model—your “profit per X” (e.g., profit per customer, per region, per product).

“The Hedgehog Concept requires a deep understanding of three intersecting circles… and the translation of that understanding into a simple, crystalline concept.” (p. 95)

Good to Great companies took the time—sometimes years—to discover this. They didn’t jump into what was trendy or opportunistic. Instead, they engaged in disciplined thought and honest assessment, guided by data and dialogue.

This concept is powerful because it brings focus. In a world of distractions and complexity, Good to Great companies succeed by doing less, but doing it better. Once they found their Hedgehog Concept, they poured their energy into it, ignored everything else, and created a flywheel of momentum.

📌 Core Lessons:

- Clarity beats complexity. Focus wins over variety.

- Your Hedgehog Concept lies at the intersection of passion, excellence, and profit.

- It’s not about being the best at everything—just the right thing.

Think about this for your own career or business: What are you naturally gifted at? What makes you come alive? What can sustainably fuel your growth?

The beauty of the Good to Great journey is that it doesn’t demand genius—it demands discipline and clarity. The Hedgehog Concept is not a quick fix. It’s a compass, guiding long-term greatness by helping organizations—and individuals—focus on what truly matters.

Chapter 6: A Culture of Discipline

In Good to Great, Jim Collins highlights that greatness doesn’t emerge from bureaucracy or micromanagement. Instead, it comes from a culture of discipline—a rare fusion of freedom and responsibility.

“When you combine a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship, you get the magical alchemy of great performance.” (p. 121)

This chapter emphasizes that Good to Great companies didn’t rely on excessive rules. They didn’t need to, because they hired self-disciplined people who took ownership of their responsibilities. These individuals didn’t wait to be told what to do—they aligned themselves with the company’s Hedgehog Concept and acted with intense focus and accountability.

One key idea is the “stop doing” list. Unlike most organizations that pile on initiatives and goals, Good to Great companies were deliberate about saying no. They consistently eliminated anything that didn’t align with their core focus. As a result, they maintained clarity and avoided the mediocrity that often comes from trying to be everything to everyone.

Collins also warns against confusing discipline with tyranny. A culture of discipline is not one where a strong leader dictates every move. Instead, it’s about building an ecosystem where disciplined people, engaged in disciplined thought, take disciplined action—without being controlled.

📌 Core Lessons:

- Good to Great companies cultivate self-disciplined teams aligned with their Hedgehog Concept.

- A “stop doing” list is as important as a “to-do” list.

- True discipline is internally driven, not externally enforced.

This chapter hits home on a personal level too. Whether managing time, money, or energy, greatness often lies not in doing more, but in doing less with greater intensity.

If you want to move from Good to Great in your own life or business, ask yourself:

- What distractions are diluting your focus?

- Are you acting from internal motivation or external pressure?

- Do your habits reflect a clear commitment to what truly matters?

Discipline, in the Good to Great sense, is freedom—not constraint.

Chapter 7: Technology Accelerators

One of the biggest surprises from Jim Collins’ research was that technology is not a root cause of greatness. While it’s tempting to think that tech gives companies a competitive edge, the truth uncovered in Good to Great is much deeper and more counterintuitive: Great companies use technology as an accelerator, not a creator, of momentum.

“Technology by itself is never a primary cause of either greatness or decline.” (p. 152)

Unlike their comparison companies, Good to Great firms didn’t adopt technology for the sake of innovation or to chase trends. Instead, they evaluated new tools based on whether they reinforced their Hedgehog Concept. If the tech didn’t align with their core focus, they ignored it—even if everyone else was jumping on board.

When technology did fit the Hedgehog Concept, these companies were often pioneers and aggressive adopters. But it was never the starting point—it was a means to amplify their disciplined strategy.

📌 Examples:

- Walgreens used technology to streamline convenience and prescription services, reinforcing their flywheel.

- Kroger invested in IT only after confirming how it aligned with customer convenience and profitability.

📌 Core Lessons:

- Don’t adopt tech because it’s cool—use it only if it accelerates your purpose.

- Greatness comes from disciplined thought and disciplined people, not tools.

- Technology is a tool, not a strategy. It should serve your Hedgehog Concept.

This is a powerful reminder in today’s AI-driven, app-saturated world. You don’t need to be on every platform or buy every shiny gadget. Moving from Good to Great means focusing on why you do something—then using the right tools to make it stronger, faster, and smarter.

Great companies aren’t tech-obsessed. They’re purpose-obsessed. And that’s why they thrive long after others fizzle out with the next passing fad.

Chapter 8: The Flywheel and the Doom Loop

If there’s one visual metaphor that captures the essence of transformation in Good to Great, it’s the flywheel.

Picture this: You’re pushing a giant, heavy flywheel. It’s hard at first. Push after push, nothing seems to happen. But then, slowly, it begins to move. With consistent effort in the same direction, it gains speed—until it spins on its own momentum. That’s what Good to Great companies do.

“There was no single defining action, no grand program, no one killer innovation, no solitary lucky break, no wrenching revolution. Good to Great comes about by a cumulative process.” (p. 165)

The Flywheel Effect

The Flywheel Effect is about building momentum through consistent effort over time. Every small action aligns with the Hedgehog Concept and builds upon the previous one. Eventually, breakthrough happens—but it feels almost inevitable, not dramatic.

All Good to Great companies followed this path. They didn’t have flashy launches or overnight wins. Instead, they made disciplined choices, hired disciplined people, and took disciplined action—again and again.

The Doom Loop

In contrast, Collins describes the Doom Loop—a deadly trap where companies jump from one idea to the next, never giving any strategy time to work. They look for a miracle, not a method. Each failed attempt leads to demotivation, rebranding, or new leadership, spiraling the organization downward.

📌 Examples:

- Kimberly-Clark quietly outpaced its competitors through steady, strategic moves—not media-hyped revolutions.

- Warner-Lambert, by contrast, lurched from acquisition to acquisition without coherence, spinning into the Doom Loop.

📌 Core Lessons:

- There’s no shortcut from Good to Great. Success builds slowly, then suddenly.

- Consistency and commitment beat flashy starts and erratic pivots.

- The real breakthrough feels like a natural outgrowth of disciplined buildup.

This chapter deeply resonates with entrepreneurs, students, leaders, and creators alike. In a world obsessed with viral moments and overnight success, the Flywheel Effect reminds us that lasting greatness is built, not hacked.

If you’re wondering how to go from Good to Great, stop looking for magic bullets. Start pushing your flywheel—one purposeful, disciplined push at a time.

Chapter 9: From Good to Great to Built to Last

In this concluding chapter, Jim Collins connects the findings of Good to Great to his earlier work, Built to Last. While Good to Great focuses on how average companies transform into great ones, Built to Last explores how visionary companies endure over decades. The two works complement each other: one is about breakthrough, the other about longevity.

“Enduring great companies preserve their core values and purpose while their business strategies and operating practices endlessly adapt to a changing world.” (p. 186)

Core Concept: Preserve the Core, Stimulate Progress

This is the central principle that bridges the Good to Great journey to lasting success. Great companies:

- Stay rooted in their core values and purpose (the “core”)

- Embrace change and evolution in strategy, methods, and technologies (the “progress”)

The beauty lies in this balance. Companies that cling too tightly to tradition stagnate. Those that chase every trend lose their identity. Good to Great companies evolve strategically without compromising their soul.

Core Ideology vs. BHAGs

Collins introduces two powerful ideas:

- Core Ideology: The deeply held values and purpose of a company. This should never change.

- BHAGs (Big Hairy Audacious Goals): Bold goals that push boundaries and energize people.

These aren’t contradictory. In fact, the combination is what drives long-term greatness. The best companies—like Sony, Johnson & Johnson, and 3M—had both enduring ideologies and radical innovation.

Leadership Development

Another insight: Level 5 leaders build successor generations of leaders who carry on the vision. They don’t just create success—they create successors. That’s the ultimate test of greatness.

📌 Core Lessons:

- Good to Great is just the beginning. Staying great requires adaptability with identity.

- Preserve your values, but don’t cling to outdated methods.

- Aim for BHAGs to inspire progress and push limits.

- Develop people and systems that outlive your leadership.

This chapter urges us not to settle. Reaching greatness isn’t the final goal. Building something that lasts—that can thrive without you—is the true legacy. The companies that move from Good to Great to truly enduring institutions are those that understand the power of both roots and wings.

Critical Analysis

Reading Good to Great in 2025 is like opening a time capsule—only to find the insights still breathe with surprising relevance. But to truly honor Collins’ scientific rigor, we must turn his methods back on his own work and ask: Does the book actually deliver on its promises? Let’s examine this across four lenses:

Evaluation of Content: How Strong Is the Evidence?

✅ What the Book Gets Right

- Data-Driven Claims: Collins didn’t start with a pet theory—he started with questions. This makes his work vastly more credible than books driven by opinion or management trends. His team sifted through over 6,000 articles and 2,000 pages of interviews over five years to back up every finding.

- Comparison Logic: Collins’ genius wasn’t just finding great companies, but contrasting them with similar companies that failed to make the leap. This “gold medalist vs. Olympic qualifier” approach helped isolate what truly mattered.

- Common Factors Across All 11 Companies: Concepts like Level 5 Leadership, the Hedgehog Concept, and the Flywheel showed up in 100% of good-to-great companies, and less than 30% of comparison companies. That’s not luck. That’s a statistically significant pattern.

“Every primary concept in the final framework showed up as a change variable in 100 percent of the good-to-great companies.”

But Here’s Where It Gets Shaky

- Survivorship Bias: As Freakonomics author Steven D. Levitt pointed out, several “great” companies like Circuit City and Fannie Mae later failed spectacularly. This raises the question—were they ever truly great, or did they just ride a temporary high?

- Retrospective Fallacy: Critics like Phil Rosenzweig in The Halo Effect argue that Collins assumes causation from correlation. For example, just because all great companies had humble leaders doesn’t mean humility caused greatness.

- Performance vs. Greatness: Collins uses stock returns as a proxy for greatness. But is financial performance the only indicator? What about innovation, employee well-being, or social impact? As Douglas Holt noted, the book can feel like a “generic business recipe” ignoring strategic uniqueness.

“Collins’ unintendedly created a proxy for greed.” — Peter C. DeMarco, The Moral Fox

Style and Accessibility: Is It Easy to Read and Understand?

Absolutely. Jim Collins writes like a thoughtful professor and a curious journalist rolled into one. His tone is warm, not arrogant. His metaphors are memorable. The Flywheel, the Hedgehog, and the Bus metaphors are so sticky that even MBA students in 2025 still quote them.

“Get the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, and the right people in the right seats.” — one of the most quoted lines in business literature

Even more impressively, Collins explains complex findings without jargon. You don’t need an MBA to understand this book. And that makes it dangerously useful—you can read it on a Sunday and change how you manage on Monday.

That said, the writing is dense at times. The first few chapters are thrilling, but the middle can slow down. You need patience to push the Flywheel.

Themes and Relevance

This is where Good to Great shines. Most management books age like milk. Good to Great ages like wine.

Relevance in 2025:

- In the age of flashy startups, Level 5 Leadership is revolutionary. In a world dominated by personal branding, influencer CEOs, and hustle culture, Collins dares to say: The best leaders are humble.

- The Hedgehog Concept remains critical in a market where companies chase too many trends. Think of how Netflix focused on streaming before anyone else, or how Canva focused only on visual simplicity.

- The Flywheel is more needed than ever. In today’s clickbait culture, where everyone wants viral success, Good to Great reminds us: Greatness is slow. Greatness is quiet. Greatness compounds.

What About AI, Remote Work, and the Digital Age?

Even here, Good to Great adapts well. Take the chapter on technology. Collins says:

“Technology alone never holds the key to greatness… It is an accelerator, not a cause.”

That insight feels prophetic. In an age where everyone’s obsessed with AI, Good to Great warns us: without discipline, clarity, and the right people—no tech can save you.

Author’s Authority: Is Jim Collins Worth Listening To?

Yes, and here’s why:

- Academic Rigor: Collins taught at Stanford, but left to pursue full-time research. He didn’t just write books—he built research laboratories for organizational excellence.

- Track Record: He followed up Good to Great with Great by Choice, How the Mighty Fall, and Beyond Entrepreneurship. Each book builds on his prior frameworks, refining them, not repeating them.

- Intellectual Humility: Unlike many self-anointed business gurus, Collins freely admits his biases, his surprises, and the things he didn’t expect to find.

“We did not begin this project with a theory to test or prove. We sought to build a theory from the ground up, derived directly from the evidence.”

That alone puts him in a league apart.

Critical Verdict: Good to Great is Mostly Great

| Criteria | Rating (out of 5) |

|---|---|

| Evidence and Methodology | ⭐⭐⭐⭐☆ (4.5) |

| Writing Style | ⭐⭐⭐⭐☆ (4.5) |

| Relevance in 2025 | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5.0) |

| Innovation | ⭐⭐⭐⭐☆ (4.0) |

| Objectivity | ⭐⭐⭐⭐☆ (4.0) |

Final Thoughts on Analysis

Good to Great is still one of the most insightful, practical, and psychologically compelling books ever written on business transformation. It is not perfect. But its imperfections are minor compared to the clarity, depth, and utility it offers.

In 2025, when startups are burning billions and layoffs trend on Twitter, Collins’ voice feels like the calm in the storm:

“Greatness is not a function of circumstance. It is a matter of conscious choice and discipline.”

Strengths and Weaknesses of Good to Great

A brutally honest, yet appreciative breakdown

After immersing yourself in the rich summary and critical evaluation, you might be asking: “Yes, but what exactly makes Good to Great a classic?” And, “Where does it fall short?” Let’s unpack both the superpowers and soft spots of the book from a deeply human and intellectually rigorous perspective.

✅ Strengths – Why Good to Great Still Stands Tall

1. Research-Driven and Rarely Speculative

Unlike most business books built around one leader’s experience or a recycled TED Talk idea, Good to Great is built from the ground up:

“We did not begin this project with a theory to test… We sought to build a theory from the ground up.”

With over:

- 6,000 articles read

- 2,000+ pages of interviews

- 384 million bytes of coded data

…the rigor is undeniable. In an era where “thought leadership” often lacks thought, Collins’ work feels like science.

2. Frameworks That Stick

Some business concepts evaporate hours after you read them. Not these.

- The Hedgehog Concept

- First Who, Then What

- The Flywheel vs. Doom Loop

- Level 5 Leadership

These aren’t gimmicks—they’re deeply intuitive and apply far beyond business. I’ve seen pastors, educators, NGO founders, even parents apply them.

“People are not your most important asset. The right people are.”

Simple. Memorable. Transformative.

Emotional Depth Without Fluff

There’s a quiet elegance to Collins’ writing. It’s never dramatic for drama’s sake, but it moves you. When he recounts how Colman Mockler (CEO of Gillette) collapsed and died the day his Forbes cover celebrated his success—it doesn’t just feel like a loss of a business leader. It feels like the end of a selfless era.

“He never cultivated hero status or executive celebrity status. Yet he led one of the greatest transformations in corporate history.”

You feel it.

4. Applicable Across Industries (Not Just Big Business)

The core ideas in Good to Great apply as easily to:

- Universities

- Startups

- Hospitals

- Government agencies

- Nonprofits

- Even creative teams

Collins emphasizes:

“It’s ultimately about one thing: the timeless principles of good to great.”

You don’t need stock options to apply this book—you just need intent and discipline.

5. An Unapologetic Love Letter to Long-Termism

In a world obsessed with going viral and scaling fast, Good to Great champions the slow, faithful path. The Flywheel metaphor—pushing again and again with no applause until momentum breaks through—is a reminder that sustainable success has no shortcut.

“No single killer innovation, no miracle moment… just turn after turn of the Flywheel.”

Weaknesses – What to Keep in Mind Before You Evangelize the Book

1. Some “Great” Companies Didn’t Stay Great

The elephant in the room: several of the 11 good-to-great companies eventually faltered.

- Circuit City went bankrupt in 2008

- Fannie Mae was bailed out in the 2008 housing crisis

- Wells Fargo was rocked by fraud scandals

Critics like Steven Levitt (Freakonomics) argue this undermines the book’s predictive power:

“If you had invested in these companies in 2001, you’d have underperformed the S\&P 500.”

While that’s partly true, remember—Collins never claimed they would always be great. He only said they once made the leap. And he later addressed this in his book How the Mighty Fall.

Still, it makes the title feel overly confident in hindsight.

2. Success = Stock Market Performance?

Throughout the book, greatness is primarily measured in cumulative stock returns. That’s a narrow lens.

- What about innovation?

- Or employee happiness?

- Or environmental and social impact?

By today’s standards, this feels incomplete—especially in the age of ESG, B Corps, and stakeholder capitalism.

That said, Collins admits his research had to anchor on objective, trackable metrics, and stock returns were the cleanest variable available.

3. Overemphasis on Leadership Behavior

Collins focuses heavily on who the leader is (humble, disciplined, focused) rather than how they build systems.

While Level 5 Leadership is inspiring, critics like Rosenzweig argue it’s part of the Halo Effect—where we attribute greatness to character traits after seeing results.

Would Darwin Smith be called humble if Kimberly-Clark had failed? Would he even be remembered?

This doesn’t mean Collins is wrong—just that some correlations might feel stronger than they are causally.

4. Doesn’t Account for Modern Startups or Rapid Scaling

Good to Great is rooted in established, often decades-old companies making a transition. It doesn’t offer much for today’s early-stage startup founders, especially those navigating:

- Hypergrowth

- VC dynamics

- AI, SaaS, platform businesses

That said, the principles are adaptable. A founder who gets the right people on the bus from day one builds a better startup than someone chasing strategy first.

5. Assumes a Fair Playing Field

Collins compares companies in the same industry, assuming similar resources. But in 2025, market dynamics are more complex:

- Network effects

- Platform monopolies

- Unequal capital access

So some “good” companies might never get the chance to become great—not because of lack of will or discipline—but due to market structure.

Still, the principles remain useful, even if results vary.

Personal Reflection: What This Book Taught Me

As a reader who juggles ambition and restlessness, Good to Great hit me in the gut. It told me:

“You don’t need to be explosive. You just need to be consistent.”

“You don’t need to scream. You need to serve quietly, with excellence.”

“You don’t need to be a genius. You need to build the right team.”

It doesn’t just reframe business. It reframes how to live.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence

When Good to Great was published in 2001, it didn’t just join the business bookshelves—it redefined them. It became a modern classic. Yet, like all landmark works, it didn’t escape critique. Let’s explore the cultural and critical footprint of this book: how it was received, praised, and sometimes torn apart.

Initial Reception: A Resounding Success

Upon its release, Good to Great soared. It sold over 4 million copies within a few years and was translated into dozens of languages. Within business circles, it wasn’t just a book—it was a manual, a checklist, a must-read rite of passage.

According to the Wall Street Journal, members of their CEO Council cited it as:

“The best management book they’ve ever read.”

The reason? It felt different. This wasn’t a book based on charisma, fads, or Silicon Valley hype. It was empirical, structured, and surprisingly humble in tone.

Executives who had grown tired of “visioneering” found Collins’ advice refreshing: get disciplined, get the right people, stop chasing shortcuts.

Influence on Leadership and Corporate Culture

Good to Great didn’t just teach leaders what to do—it reshaped what kind of leaders people aspired to be.

It shifted the model from:

- Loud, heroic CEOs

- Obsession with quarterly growth

- Strategy-first mindset

To:

- Level 5 humility and fierce resolve

- People-first discipline

- Long-term, flywheel-driven greatness

Major companies from Microsoft to Starbucks adopted frameworks from the book in internal training. Harvard Business School included the Flywheel and Hedgehog Concept in leadership courses. At one point, even military units and nonprofits referenced the book to improve strategic decision-making.

The “First Who, Then What” philosophy changed how hiring, succession planning, and team building were approached across industries.

Critical Acclaim

- Publishers Weekly called it:

“Worthwhile… deeply researched… simple and commonsense.”

- Time Magazine named it one of the 25 Most Influential Business Management Books of all time:

“A deeply-researched analysis… with rare staying power.”

- Jim Collins was soon regarded as the Peter Drucker of his generation—a thinker more interested in timeless truths than trendy tactics.

Criticism: The Backlash from Academia and Data Realists

Yet, not all reactions were rosy.

As time passed and some “great” companies stumbled, a wave of scholars and thinkers began to question the book’s core premise. Could it be that Collins had mistaken luck for discipline? Or had he confused correlation with causation?

Let’s examine the most pointed criticisms:

1. Survivorship Bias – The Circuit City Problem

Steven Levitt, co-author of Freakonomics, noted that many of Collins’ “great” companies either declined or failed post-publication.

For instance:

- Circuit City: Once praised for 18.5x market returns, it filed for bankruptcy in 2008.

- Fannie Mae: Became a cautionary tale in the 2008 financial crisis.

- Wells Fargo: Rocked by multiple ethical scandals.

Levitt wrote:

“Had you invested in the 11 companies when the book came out, you would have underperformed the S\&P 500.”

Implication: Past greatness doesn’t guarantee future performance—and Collins may have unknowingly cherry-picked companies based on hindsight.

2. The Halo Effect – Attributing Success to Personality

Phil Rosenzweig, author of The Halo Effect, argued that Collins mistook outcome-based narratives for cause-based truths.

“He uses magazine profiles and retrospective interviews—data rife with the ‘halo effect.’”

For example, he found “humility” in leaders who succeeded. But would anyone have described them that way if they had failed? Perhaps not.

It raises the question: Did Collins describe who these leaders were… or who we wanted them to be?

3. Too Simplistic – The “One Size Fits All” Trap

Holt and Cameron, authors of Cultural Strategy, critiqued the book for offering:

“A generic business recipe that ignores the complexity of strategic opportunities and cultural contexts.”

They argued that the Hedgehog Concept oversimplified how companies succeed—and could mislead organizations into overspecialization.

4. Capitalist Moralism – A Proxy for Greed?

Peter C. DeMarco, in his essay The Moral Fox, had a unique take:

“Collins unintentionally created a proxy for greed by placing ‘good’ in opposition to ‘great.’”

His concern: In equating greatness with stock returns, Collins may have promoted a culture of value extraction over value creation.

Collins’ Response to Criticism

To his credit, Jim Collins never ducked criticism. He acknowledged that not all “great” companies stayed great—but reminded readers:

“The book never promised they would always be great—just that they were once great by the standards we measured.”

He even published follow-ups:

- How the Mighty Fall – on why great companies collapse

- Great by Choice – on how companies thrive in chaos and uncertainty

This willingness to adapt, clarify, and refine his own work is a hallmark of intellectual honesty.

Legacy and Ongoing Impact

Despite the criticisms, Good to Great remains:

- 📘 A staple in MBA curriculums

- 🏢 A blueprint for many Fortune 500 transformations

- 🎓 A crossover text used in non-business disciplines like education and policy

- 🎤 A cultural artifact that changed the conversation around leadership

And most importantly—it continues to sell, teach, and resonate in 2025, nearly 25 years after publication.

“Good to Great is still the most borrowed business book in most university libraries,” according to the 2023 Financial Times global business reading report.

In Summary: Reception at a Glance

| Audience | Reaction |

|---|---|

| CEOs & Executives | “A timeless blueprint for leadership and team-building.” |

| Academics | “Well-researched but vulnerable to hindsight bias and oversimplification.” |

| Critics & Economists | “Useful, but outcome-biased. Not predictive. Sometimes too moralistic.” |

| General Readers | “Relatable, clear, practical—even if I’m not in business.” |

Comparison with Other Works

Good to Great stands out in the business literature landscape due to its research-backed insights, emphasis on disciplined leadership, and the now-famous concepts of the Hedgehog Concept and Flywheel Effect. However, when compared to other influential titles, its uniqueness—and its limitations—become clearer:

1. Built to Last by Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras

While Good to Great focuses on transformation, Built to Last explores how visionary companies sustain greatness over time. Both books are complementary, but Good to Great is more about how to start the journey, whereas Built to Last is about how to continue it. In fact, Chapter 9 of Good to Great bridges these two works.

2. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

Covey’s book leans toward personal leadership and character development, making it more universal and self-help focused. Good to Great, by contrast, is firmly rooted in organizational transformation and corporate strategy. Covey talks about being “principle-centered,” which aligns philosophically with Collins’ idea of Level 5 Leadership, but with different applications.

3. Start with Why by Simon Sinek

Sinek argues that companies succeed when they focus on why they do what they do—an idea that resonates with Collins’ Hedgehog Concept.

However, Start with Why is more about inspiration and marketing, whereas Good to Great focuses on internal discipline and operational clarity. Both emphasize purpose but from different angles.

4. The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

Ries’ work is startup-focused and stresses fast iteration, MVPs (Minimum Viable Products), and agile pivots. While Good to Great highlights disciplined thought and action over years, The Lean Startup is about rapid testing and learning. They contrast in pace and context—one is for mature firms seeking greatness, the other for early-stage ventures trying to survive.

5. The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen

Christensen explores why successful companies often fail due to disruptive innovation—a theme only lightly touched in Good to Great.

While Collins focuses on what companies did right to become great, Christensen warns of what even great companies can do wrong when they ignore emerging technologies or new markets. Together, they provide a fuller picture of business success and failure.

Conclusion

Reading Good to Great is like being handed a compass in a foggy forest. You might not instantly see the exit, but you’ll know which direction to walk—and more importantly, why. Even two decades after publication, Jim Collins’ message continues to resonate across boardrooms, classrooms, startups, and even nonprofits.

Summary of Key Insights

Let’s briefly revisit what Good to Great teaches us—and why it still holds power today:

- Start with “Who,” Not “What”: Great transformation begins by getting the right people on the bus. Without the right team, no strategy can survive.

- Level 5 Leadership Wins: Quiet humility and fierce resolve—this paradoxical mix leads companies through turbulence better than charisma.

- Brutal Facts Are Fuel: Honesty doesn’t hinder hope; it anchors it. Facing reality head-on is how great leaders navigate crises.

- The Hedgehog Concept Creates Focus: You need clarity on three intersecting truths: what you’re best at, passionate about, and what drives your economic engine.

- The Flywheel Builds Momentum: Lasting greatness is not sparked by one “big moment” but by continuous, disciplined effort over time.

- Technology Is an Accelerator: Tech cannot create greatness, but it can multiply the momentum you’ve already built.

- A Culture of Discipline Enables Freedom: Discipline is not about micromanaging—it’s about giving responsibility to those who will thrive under it.

These principles aren’t just theory. They’re built on rigorous research, and despite some companies falling from grace over time, the frameworks remain durably applicable.

Why This Book Still Matters in 2025

Let’s face it—we live in an era of disruption. AI, remote work, economic uncertainty, and rapid innovation are turning industries upside down. You’d think a book written in 2001 would feel dated.

Yet Good to Great doesn’t. Why?

Because it focuses on first principles, not fads.

While the tools have changed (Zoom instead of in-person meetings, AI instead of data crunchers), the human fundamentals Collins discusses remain timeless. People still matter. Discipline still matters. Truth-telling and long-term focus still matter.

Even in today’s agile startups and fast-scaling tech companies, the Hedgehog Concept helps clarify identity. The Flywheel remains a reliable metaphor for compounding effort. And Level 5 leadership? It’s never been more relevant in a world exhausted by narcissistic, short-term-minded CEOs.

Who Should Read Good to Great?

✅ Entrepreneurs

If you’re building a company, this book offers the architecture to scale with integrity and endurance.

✅ CEOs and Managers

It forces you to evaluate your team, your leadership style, and your long-term strategy with brutal honesty.

✅ Students of Business or Leadership

The frameworks here offer a masterclass in strategic thinking, organizational behavior, and ethical leadership.

✅ Nonprofit Leaders

Collins’ Good to Great and the Social Sectors (a companion monograph) tailors these principles to purpose-driven organizations.

✅ Anyone Tired of “Quick Fixes”

If you’re disillusioned by motivational fluff and want something grounded, actionable, and humble—this book is your remedy.

Final Verdict

Is Good to Great still relevant?

Yes—more than ever.

Is it perfect?

No. Some companies Collins praised, like Circuit City and Fannie Mae, later stumbled. The methodology has its limitations.

But here’s the truth: Good to Great doesn’t promise immunity from change. It teaches you how to build organizations that can evolve, withstand chaos, and keep moving forward—not with flashy revolutions, but with disciplined revolutions of the flywheel.

If you only read one business book this year, let it be this one.