Many of us feel like outsiders in the communities that claim us—and Angela Buchdahl’s Heart of a Stranger shows, step by careful step, how to turn that ache into belonging. In a world that sorts people by boxes and bloodlines, this memoir offers a usable blueprint for wholeness—religious, cultural, and deeply human.

It begins with a game-show clue and ends with a covenant you can practice in daily life. The problem it quietly solves is this: how do you lead—and love—when you feel you don’t fully “qualify”?

Because identity is rarely pure, and belonging is almost always built.

Belonging isn’t inherited or gatekept; it’s chosen and practiced—through courage, covenant, and the everyday work of seeing the stranger as kin.

Snapshot

The book grounds its claims in lived experience—e.g., the Jeopardy! clue that cheekily defines “rabbi” with Buchdahl’s photograph and firsts, “the first Asian American to be ordained a cantor1 as well as [a] leader of a Jewish congregation,” which she recounts in her Introduction.

It situates that moment in American legal and social history (her parents’ 1968 interracial marriage one year after Loving v. Virginia), then braids spiritual midrash with autobiographical detail.

Externally, demographic research anchors the wider story: Pew estimates ~7.5 million Jewish adults and children in the U.S., a community increasingly diverse by race and background.

Institutionally, Central Synagogue—where Buchdahl serves—reaches “more than 3,000 member families” with “a livestream community numbering in the hundreds of thousands,” offering a public test case for her inclusive rabbinate.

Heart of a Stranger is best for readers wrestling with mixed identities, interfaith families, leaders of faith or civic communities, and anyone who’s ever felt “not enough” for the room they’re in.

Not for readers demanding strict gatekeeping or partisan polemics; this is a pastoral, text-rich memoir-sermon hybrid, not a culture-war screed.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

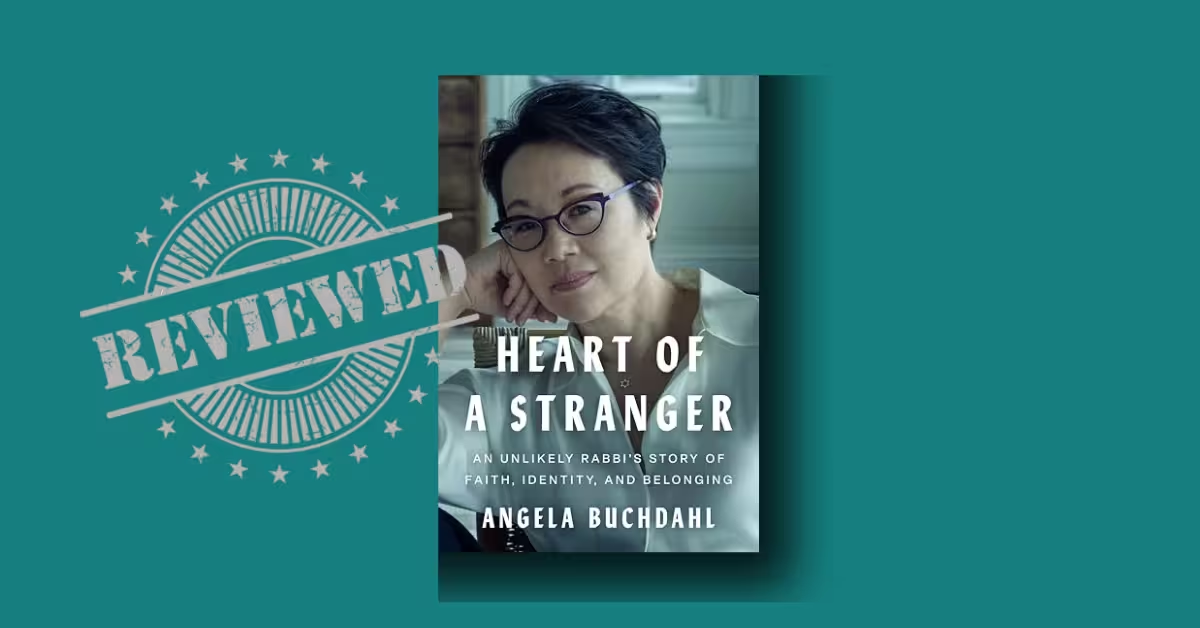

Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging by Angela Buchdahl.

The book opens with a now-famous scene: on December 29, 2021, Jeopardy! champion Amy Schneider selects the $800 clue in “I Am Woman,” and up pops a photo of Buchdahl in a purple-striped tallit; the clue reads, “Korean-born Angela Buchdahl is the first Asian American to be ordained a cantor as well as this leader of a Jewish congregation.”

It’s a wry setup for a serious project: a memoir that is also a set of sermon-essays pairing life stories with Hebrew keywords—Echad (Oneness), Zehut (Identity), Tikkun (Repair)—so that narrative and liturgy illuminate each other.

Buchdahl’s credentials are singular: first Asian American ordained a cantor (1999) and a rabbi (2001), now senior clergy at New York’s Central Synagogue; external histories corroborate these milestones and her leadership profile.

Context. Genre-wise, this is literary spiritual autobiography braided with public theology—call it “memoir-with-midrash.” The chapters alternate between granular scenes (Tacoma potlucks, Shabbat rice when challah wasn’t available) and theological reflections (why Shema2 is recited at deathbeds).

Her background—Korean Buddhist mother, Jewish American father—animates her reading of Echad (“God is One”), reframing monotheism as wholeness and interdependence rather than supremacy: “‘God is One’ was never about preeminence or dominance, but rather wholeness… if everything is one, then we all belong to this mountain, to the earth, and to each other.”

Purpose. The purpose is explicit: Judaism’s most ancient command is to love the stranger—and the most Jewish thing about a Jew of mixed background might be precisely the experience of strangeness. “Feeling like the stranger might be the most Jewish thing about me.”

2. Background

Buchdahl’s Introduction links her life to a larger American timeline: “A story that could only happen in America… when I entered the world, in the seventies, thanks to its pioneers and revolutions.”

Her parents’ 1968 marriage in Seoul occurred just after Loving v. Virginia (1967) lifted interracial bans nationwide, a hinge she cites to show how law creates space for new families—and new rabbis.

Arriving in Tacoma in 1977, her childhood synagogue (Temple Beth El) became home; there, a father’s refrain jammed against community ambivalence: “There is no such thing as half-Jewish… You are all of it.”

This home was textured and specific—gold-star Sunday school charts and rice standing in for challah—demonstrating how practice, not pedigree, builds peoplehood.

3. Heart of a Stranger Summary

This is the one-stop, no-looking-back, broad extended summary of Angela Buchdahl’s Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging—braiding its scenes, teachings, dates, and arguments into one flowing narrative, with key lines quoted exactly where it matters.

The memoir begins with a pop-culture jolt: on December 29, 2021, Jeopardy! flashed a photo of Buchdahl and asked, “Korean-born Angela Buchdahl is the first Asian American to be ordained a cantor as well as this leader of a Jewish congregation,” a clue that frames her story as an “unlikely rabbi” whose path “could only happen in America.”

From there the book unfolds as a sequence of vivid life chapters paired with Hebrew key-words—Echad (Oneness), Zehut (Identity), Shabbat (Rest), Dimah (Tears)—so that scenes from Tacoma, Jerusalem, and New York become living commentaries on scripture and community.

And through that braid Buchdahl advances her central argument: belonging is covenantal and practiced, not racial or gatekept—a thesis she grounds in autobiography, rabbinic sources, and the real-time pressures of leading a large American synagogue through pandemic, racial reckoning, and the aftershocks of October 73.

Highlights at a glance

Buchdahl’s parents marry in 1968, one year after Loving v. Virginia—she calls her trajectory “a story that could only happen in America,” tying her very existence to legal and social openings.

Her signature theological lens—Echad (Oneness)—is taught not in a classroom but on a mountain hike above Tacoma as her mother says, “Feel the rock under you… Be one with the mountain,” which she translates into “God is One” as wholeness rather than dominance.

Her adolescent and college years sharpen the ache of otherness: a chapter asks “Which Box Do I Check?” as she confronts shibboleths4 —literal and figurative—that keep her “Jewish to [her] core” from “get[ting] past the guards.”

In 1983 the Reform movement’s patrilineal descent policy becomes a turning point in how others see (and contest) her Jewishness; years later a summer in Israel and a conversation with Rabbi Elliot Dorff recast giyur (conversion) as “an acknowledgment and embrace of the Jewish soul that has always been in you.”

At the mikvah in Seattle—during a winter break in college—she ritualizes that inner belonging with a Reform beit din, naming it a “reaffirmation ceremony,” not a negation of who she already was; she emerges claiming the “many threads” that make up her Judaism.

As a rabbi, she narrates pandemic pivots in 2020—“our online Shabbat community grew exponentially,” virtual funerals, and a daily meditation that starts with >150 people and swells to >400—and then moves into terrains of race, security, and war with chapters like “Reckoning with Race,” “He Has a Gun,” and “October 7.”

Detailed summary

The thread starts at a trailhead—literally.

In the opening section “The Mountain,” Buchdahl recalls a family hike in Washington State where her Korean Buddhist mother stages a picnic as pedagogy: “Be one with the mountain,” she says, and suddenly Shema’s “Adonai Echad” is no longer “our God is number one,” but “wholeness”—a metaphysic of interdependence she will later preach at hospital bedsides as families whisper the Shema at life’s thresholds. “Oneness is about unity, interconnectedness; if everything is one, then we all belong to this mountain, to the earth, and to each other.”

That wholeness stands against the slicing forces of identity policing. Through school, camp, and Yale, she remembers the coded passwords of cultural insiderism—“shibboleth”—and how even praise (“you just look Jewish to me now”) could erase the Korean face her friend no longer saw.

She translates the ache into teaching: Zehut (“identity”) literally derives from zeh (“this”), so your Jewishness is your thisness, not a comparison to someone else’s mold. “We won’t be asked why we weren’t that. We will be asked why we weren’t this.”

A Jerusalem summer thickens the crisis. Seeking to interview an Orthodox songwriter for her senior thesis on women in the cantorate, she is rebuffed because the artist “can only teach Torah to Jews”—ironic, she notes, because that songwriter is herself a convert. The sting propels her into what she calls “hitting the wall.”

And then a conference in New York offers grace. In a CAJE session nicknamed “Choir,” the late Debbie Friedman says, “We are all broken… once we acknowledge that, we can start the healing,” and a young Angela feels the cracks open into catharsis. Another teacher, Rabbi Elliot Dorff, reframes giyur not as repudiation but recognition—“not as a total transformation but as an acknowledgment and embrace of the Jewish soul that has always been in you”—allowing Buchdahl to see conversion as a ritual seal on a lifelong reality. “I could now understand giyur not as turning into something new but as a reaffirmation of the Jew I always was.”

Her decision culminates at the Sephardic Bikur Holim mikvah in Seattle, accompanied by a Reform beit din. She enters “wearing glasses rather than contact lenses,” stripped of adornment, speaks gratitude for a Jewish father’s inheritance and a Buddhist mother’s spiritual vocabulary, and names a larger American truth: “we are all, in a sense, ‘Jews by choice.’” The immersion becomes an exclamation point rather than a change of species.

From here the book arcs into vocation. Early rabbinic years carry the loneliness of being the “child” of a community that struggles to see you as fully grown; the chapters on mentorship, music, and motherhood show a clergy life knit together by friends (chaver), song (shira), and humility (anavah).

In a set-piece at the 2013 Reform Biennial—six thousand attendees—her mother confronts a gatekeeper at the convention center: “Is this the Jewish convention? … Well, then, this is where I belong. My daughter is leading services… She is the rabbi!” The line lands as both punchline and thesis.

Then the world stops. In March 2020, days before her planned sabbatical, Covid shutters the city and Buchdahl’s small team constructs a Franken-sanctuary of ring lights, art books, and green screens to stream Shabbat to an empty room. “Our online Shabbat community grew exponentially… a reimagined congregation… spanning time zones,” she writes; Zoom funerals begin; April–May 2020 sees “three times the number of deaths” of a normal two-month stretch.

Yet care adapts: volunteers call the homebound, colleagues pickle on “What’s the Dill?” and music fills Facebook Live.

Out of pastoral triage she seeds a daily morning meditation. Expecting almost no one, she’s stunned when >150 people dial in day one; within weeks >400 stay for ten minutes of teaching and twenty of silence.

Together they count the Omer (“numbering our days” in quarantine), mourn George Floyd in May 2020, and practice teshuvah. “This six-month experiment changed my spiritual practice,” she writes; the communal sabbatical teaches her how to rest.

“Reckoning with Race” arrives not as theory but as a congregant’s email. A Black member writes that “on a weekly basis this Jewish community makes me feel like an outsider,” recounting being followed by security and peppered with “Are you Jewish?”

The wound reopens, and Buchdahl preaches against the false race story—“it’s time, once and for all, to stop seeing Jewish Peoplehood as a race… we are a family connected by something stronger than blood; we are bound by our covenant with God”—anchoring the claim in Exodus’s erev rav, the “mixed multitude” that left Egypt with Israel.

Security and vulnerability collide in “He Has a Gun.” During Shabbat, she receives a voicemail from Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker in Colleyville—“This is not a joke. There is an actual gunman here and he wants to speak to you”—a chilling reminder that the rabbi’s role is both spiritual and tactical, and that the stranger’s heart includes fear.

Then October 7. The war’s grief threads through every subsequent sermon as Buchdahl wrestles publicly and personally. She writes of tears—dimah, cognate with dam (blood) and ayin (eye)—and of learning again that “to cry is literally to be human,” tracing Joseph’s eight weeping episodes before he reconciles with his brothers.

She admits avoiding the “thorniest moral questions” at first, then voices the rabbi’s task: not omniscience but the stubborn pursuit of peace, “trusting in an outcome for which there is no other alternative.”

Her empathy is sharpened by a mother’s testimony: Rachel Goldberg-Polin, whose son Hersh was held hostage for 328 days, speaks of tears that taste the same “over there,” and Buchdahl lets that salt breach her own one-sided grief so that compassion can widen, even amid war.

Across these late chapters the old thesis returns with historical heft: Pharaoh first racialized the Hebrews to justify oppression; Spain’s Inquisitors counted “impure” blood; Nazis forged pseudoscience; and still today some insist on “a look.”

The corrective is ancient—erev rav, a “mixed multitude”—and contemporary: Jews in Israel are majority non-Ashkenazi; American Jews include many who are Black, Brown, Asian, adopted, descended from Iraq and Yemen, or who “became Jews by Choice.” The book therefore argues for covenantal belonging: “Every Jew who feels responsible to this covenantal relationship should be counted as an equal.”

By the end, the memoir circles home. The “unlikely rabbi” is no longer unlikely; she is inevitable—a product of pioneers and revolutions, a mother’s mountain and a father’s synagogue, a mikvah in Seattle and a sanctuary held together with Scotch tape. “Feeling like the stranger might be the most Jewish thing about me,” she writes, not as resignation but as vocation: a blueprint for building communities where the question “Are you Jewish?” is met—like in her famous anecdote—with an unflinching “YES.”

Thematic spine

Identity is this, not a test you can fail—because zehut comes from lived distinctiveness and covenantal responsibility, not bloodline purity or accent; as she teaches B-Mitzvah students, “There has never been another person exactly like you, and there never will be again.”

Belonging is practiced in community—e.g., virtual Shabbat rising out of crisis, daily meditation that unexpectedly gathers hundreds, and pastoral innovation when funerals must move to Zoom, all of which demonstrate that a people bound by time-hallowed rituals can still improvise fidelity.

Peoplehood is not race—it is a “mixed multitude” project from Exodus onward, and American synagogues must unlearn reflexive border-guarding (the modern “shibboleths”) if they want everyone who shoulders the covenant to be “counted as an equal.”

Sorrow does not cancel empathy—the long year after October 7 demands tears with eyes (dimah: blood + eye), and the road to peace requires what she calls faith’s stubbornness: to keep uttering the word, and making the smallest steps, when it feels naive to hope.

And woven through: a mother’s line about finding your monk; a congregation that becomes a testing ground for inclusion; and a lifetime of “boundary crossing” that starts, factually, in 1968 and becomes theology on every page.

Chapter-constellation

“Introduction”: “On December 29, 2021… ‘Korean-born Angela Buchdahl is the first Asian American to be ordained a cantor as well as this leader of a Jewish congregation.’… This is the story of an unlikely rabbi.”

“The Mountain — Echad (Oneness)”: “The verse we repeat—‘God is One’—was never about preeminence… but rather wholeness… we all belong to this mountain, to the earth, and to each other.”

“Which Box Do I Check? — Zehut (Identity)”: “I couldn’t pronounce ‘shibboleth’… Jewish to my core, I still wouldn’t get past the guards.” And: “We won’t be asked why we weren’t that. We will be asked why we weren’t this.”

“Don’t Call It Conversion — Shevarim (Brokenness)”: Dorff’s reframing: “Judaism sees giyur… as an acknowledgment and embrace of the Jewish soul that has always been in you.”

“Mikvah” (Seattle, senior year winter break): “I affirmed that in America today, we are all, in a sense, ‘Jews by choice’… I was not a ‘new Jew’… this ancient ritual became the exclamation point.”

“Pandemic 2020 — Shabbat (Rest)”: “Our online Shabbat community grew exponentially… a reimagined congregation that… spanned time zones.” And: morning meditation grows to “more than four hundred” daily.

“Reckoning with Race — Erev Rav (Mixed Multitude)”: “The idea of Judaism as a ‘race’ is a construct… Jews have never been just one color… in 2019… Jews of Color… at least 12 to 15 percent… about a million.” And: “We are bound by our covenant with God.”

“October 7 — Dimah (Tears)”: “To cry is literally to be human… In the months after October 7, weeping became routine.” Then the pastoral turn toward peace: “God wants us to work toward a path to peace.”

The practical takeaways

You can practice Echad by noticing how ritual and world, grief and gratitude, are not separate categories: say the Shema at the hospital bed and feel the “circle around him” that will be the dying man’s real legacy.

You can practice Zehut by asking “What makes you you?” and refusing borrowed yardsticks—this is why, she tells 12-year-olds, your job is to discover “the particular job that you’re on this earth to do.”

You can practice Shabbat by building “a palace in time,” not just a life of rooms—letting sacred time rehabilitate purpose when productivity’s staircase leads nowhere.

You can practice Erev Rav by welcoming difference as founding DNA, not a problem to solve—that’s true of Jews and, she adds, of America: “a mixed multitude… bound by a striving for liberty… for all its citizens.”

You can practice Dimah by letting tears (yours and others’) be the doorway to moral imagination, the first step back toward saying “peace” without irony.

4. Heart of a Stranger Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Buchdahl supports her argument with layered evidence: autobiographical scenes that ring true, textual readings that open scripture, and institutional data points that show impact beyond the page.

Consider the Echad chapter: a mother’s mountain lesson (“Be one with the mountain”) reframes the Shema from competition to communion; the meditation extends seamlessly into bedside pastoral care where the Shema is the braid that binds a dying man to his family and his people.

That’s memoir and midrash, not proof-texting; it’s lived hermeneutics.

Then there’s the Identity arc: the book doesn’t paper over gatekeeping; it puts it on the page. The line “There is no such thing as half-Jewish” sits beside the ache of being treated as a lifelong “resident alien” (ger toshav), welcomed yet never fully counted.

The chapter “Don’t Call It Conversion” deepens the argument with rabbinic ethics: giyur, she learns, is best understood not as repudiation but as recognition—an embrace of the Jewish soul you already live.

This matters because it reorients policy debates toward dignity: set the bar of belonging at covenantal responsibility, not phenotype or maternal lineage alone.

On scope and contribution, the book is timely and concrete. External evidence corroborates the stakes: the American Jewish population is large (≈7.5 million) and diverse; gatekeeping that overlooks Jews of Color risks social self-harm. (Buchdahl herself estimates “about a million are Jews of Color,” then argues to “stop seeing Jewish Peoplehood as a race.”)

Meanwhile, her pulpit is both literal and global: Central Synagogue’s member base and livestream reach indicate that her teachings are field-tested in one of the country’s most visible congregations.

Does the book fulfill its purpose?

Yes, because it converts biography into practice.

The practical ethic surfaces in micro-commandments that read like life liturgy: “You can only love as much as you feel lovable… Get quiet enough to hear your heart. Remember you are worth hearing. You are worth loving.”

This is not a hallmark-card aside; it’s the baseline spiritual psychology that enables her larger claim: a people called to love the stranger cannot do so from self-contempt.

The teaching lands beyond synagogue walls. Her Yom Kippur sermon—“Yes! I am Jewish”—went “viral (by sermon standards),” adopted in college syllabi and even a Nordstrom training; the resonance included those far outside her demographic.

We see how a single leader’s clarity can unfreeze a communal posture.

5. Reception, criticism, and influence

Mainstream coverage frames the memoir as “eloquent” and inclusion-forward: Kirkus emphasizes its braided form—story plus sermons—and its insistence that a calling is inseparable from inclusion.

The Jewish Book Council likewise highlights the structure—part memoir, part sermon collection—recognizing it as both intimate and portable for study groups.

Not all commentary is celebratory; one recent polemical Substack essay objects that Buchdahl is “selectively silent” about urban antisemitism, an example of the political cross-pressure visible clergy face.

Yet the broad, popular-cultural imprint is real: when Jeopardy! used her as a clue during Amy Schneider’s historic run, a mass audience learned that an Asian American woman could be the face of “rabbi.” News outlets documented that moment’s symbolism—and its humor.

Within religious leadership circles, Central Synagogue’s scale and broadcast infrastructure mean her sermons function as national touchpoints—what happens in that sanctuary seeds adult education curriculums elsewhere.

6. Comparison with similar works

Place Heart of a Stranger beside other rabbinic memoirs and public-theology texts and a pattern emerges.

Like Rabbi Sharon Brous’s The Amen Effect (communal repair via attention) or Abby Pogrebin’s interview-driven portraits, Buchdahl writes a book you can bring to a living room or a beit midrash: narrative first, practice next. (A recent podcast lineup that pairs these authors shows the shared ecosystem.)

Unlike purely academic treatments of identity, her book is heavy with scenes—rice for challah, a mountain in Tacoma as a Buddhist-Jewish temple—so that theory descends into gesture. “Use chopsticks to take the hot bulgogi off the grill… Be one with the mountain.”

And unlike memoirs that resolve into individual triumph, this one keeps circling back to covenant—a we that includes converts, adoptees, and ancestral insiders alike: “We are a family connected by something stronger than blood… bound by our covenant with God.”

7. Conclusion

Read this if you crave a spiritually serious, emotionally honest account of how identity is formed by practice, not purity.

General readers will appreciate the storytelling; clergy and educators will mine the chapter-word pairs (Echad, Zehut, Tikkun, Dimah) for teaching; interfaith families will feel seen; leaders in any tradition will find a model for widening the tent without collapsing its spine.

If you come looking for polemics, you’ll be frustrated; if you come looking for wisdom that can be lived, you’ll leave with a handful of rituals and a heart trained to see the stranger.

And if you’ve ever answered “Are you Jewish?” with a startled “YES!,” this book will feel like home.

8. Heart of a Stranger Quotes

- “Korean-born Angela Buchdahl is the first Asian American to be ordained a cantor as well as this leader of a Jewish congregation.” (Jeopardy! clue as quoted in the book’s Introduction.)

- “A story that could only happen in America… when I entered the world, in the seventies, thanks to its pioneers and revolutions.”

- “‘God is One’ was never about preeminence or dominance, but rather wholeness… if everything is one, then we all belong to this mountain, to the earth, and to each other.”

- “There is no such thing as half-Jewish… You are one hundred percent Jewish… Korean… American. You are all of it.”

- “Feeling like the stranger might be the most Jewish thing about me.”

- “We are a family connected by something stronger than blood; we are bound by our covenant with God.”

- “You can only love as much as you feel lovable… Get quiet enough to hear your heart.”

Notes

- A religious official who leads congregational singing and prayer in a synagogue ↩︎

- Refers to the central Jewish prayer, a declaration of faith beginning with the Hebrew words “Shema Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad ↩︎

- On October 7, 2023, Israel was struck by terrorist attacks of an unprecedented scale and brutality in the worst anti-Semitic massacre since the Holocaust. These barbaric attacks, which were carried out by Hamas and other affiliated terrorist groups, took the lives of at least 1,219 people and led to the taking of 251 hostages, most of them Israeli civilians ↩︎

- A custom, principle, or belief distinguishing a particular class or group of people, especially a long-standing one regarded as outmoded or no longer important ↩︎