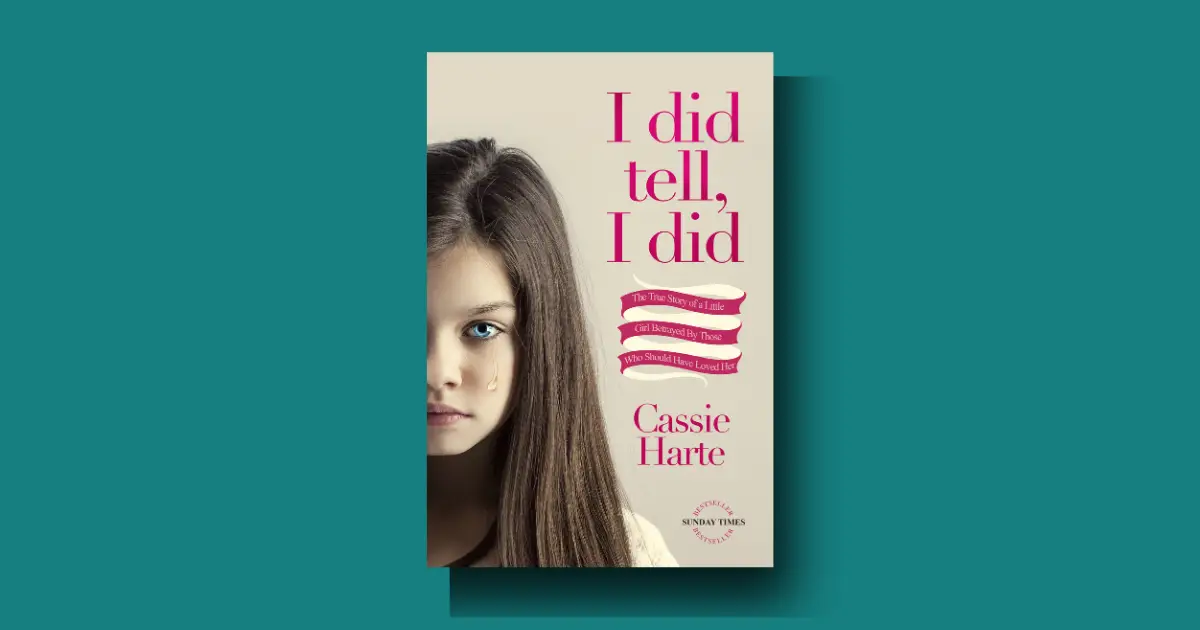

I Did Tell, I Did: The True Story of a Little Girl Betrayed by Those Who Should Have Loved Her is Cassie Harte’s memoir, first published in Great Britain in 2009. The book is structured into 23 chapters plus an epilogue, which matters because the story moves in deliberate stages rather than one continuous recollection. Harte also notes that some details (including names and places) have been changed.

I Did Tell, I Did is for the moment a child speaks up and the adult who should protect them says, “No.” It shows what that disbelief does to a mind, a body, and a whole adult life.

When a child tells the truth and nobody acts, the trauma doesn’t end—it mutates into silence, coping, and patterns that take decades to unlearn.

Proves: In England and Wales, the ONS estimates that nearly 30% of adults experienced childhood abuse (emotional, physical, sexual, or neglect), with sexual abuse reported by 9.1% overall in the year ending March 2024 data. Globally, UNICEF estimates 650 million girls and women alive today experienced sexual violence in childhood, and WHO reports 1 in 5 women and 1 in 7 men report having been sexually abused as a child.

I Did Tell, I Did is best for readers who want an unvarnished survivor memoir that names the mechanics of grooming and the lifelong fallout of being dismissed. It is not for readers who want distance, or who prefer trauma narratives with light detail and heavy abstraction.

If you are sensitive to content about child sexual abuse, neglect, and coercive control, please treat this as a serious trigger warning before you continue.

The “problem” it solves is not entertainment—it is understanding how abuse hides in plain sight and how recovery actually looks in adult years. And yes, it can be emotionally exhausting in the way only first-person testimony can be.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

At its heart, I Did Tell, I Did argues that the worst damage is often done after the abuse—when adults deny, minimize, or protect the perpetrator.

The emotional tone is established immediately by how Harte recalls being told she was unwanted, including the line, “I never wanted to have you,” and the repeated refrain that she “ruined” her mother’s life. She pairs that with a broader warning about vulnerability and predation: “Evil people target the vulnerable,” which frames the memoir as both personal and cautionary. The dedication is explicit about who she is writing for: “For every child who has ever suffered at the hands of an abuser… To every child who has ever been too scared to tell.”

On author background, public catalog copy describes Harte as a survivor who later built a family life, and Google Books describes her work in counselling while also claiming she runs a practice as a counsellor and psychiatrist, which I cannot independently verify beyond that listing. Even without credentials, the authority here comes from the granular way she documents coercion, shame, and survival choices.

What makes the memoir historically sharper is the quiet background fact she states: “Back in 1971 there was no state help for unmarried mothers.”

The purpose is not just to recount harm, but to show how institutions and families can become an abuser’s best camouflage, especially when a child’s disclosure is treated like inconvenience instead of emergency. The book’s own internal thesis is basically: telling is not the finish line; being believed is.

That emphasis matches safeguarding research that shows negative disclosure experiences are common and that belief and protective action are key to better outcomes.

It also aligns with the IICSA discussion of barriers to reporting and why abuse stays unspoken. And it sits inside a bigger public-health picture where abuse is widespread but often hidden, as WHO notes.

So while it reads as one person’s life, it also functions as a practical map of how silence is manufactured.

2. Background

Before the abuse is “a plot,” it is a home atmosphere, and Harte describes that atmosphere as cold, punitive, and humiliating.

In early chapters she introduces the family dynamics bluntly, including the violence and contempt that shaped her sense of self. She describes a particular kind of double-life parenting—how her mother could keep a respectable exterior while the children lived with fear. She also frames her own childhood as one where affection was a scarce resource that could be weaponized.

That context matters because grooming often succeeds not through force at first, but through need.

“Uncle Bill,” her mother’s lover, enters as the adult who offers attention, treats, and a confusing kind of “specialness.”

Harte describes him giving gifts and attention while her mother simultaneously labels her “an unfortunate mistake,” which is exactly the emotional gap a groomer exploits. She recalls being collected in a car and getting opportunities to be alone with him, and I Did Tell, I Did emphasizes how that access was normalized around her.

Over time, the reader watches affection become leverage, and leverage become threat. But what hits hardest is how “love” is used as a trap: “I’ll let you do it, because I love you,” she remembers thinking as a child.

The abuse begins as boundary testing and “play,” and she explicitly identifies those early touches as the start.

From here, the memoir moves into the core narrative, and I’m going to summarize it in full.

3. I Did Tell, I Did summary

I Did Tell, I Did unfolds like a slow tightening: the more Cassie tries to speak, the more the adults around her close ranks.

One of the I Did Tell, I Did’s pivotal scenes is her attempt to tell her mother, and the response is catastrophic. She describes seeing her mother kiss Bill—an image that lands like proof that the power structure is fixed—and then hearing, “I’ve had enough of your lies… It’s time for you to go,” followed by the threat of a children’s home. In that moment, the memoir’s title becomes bitterly literal: she did tell, and it still didn’t save her.

After that, Harte describes becoming watchful and strategic, because telling the truth has been redefined as the danger.

She writes about scanning for the sounds of Bill returning and the physical fear response that never really turns off. She describes being too frightened to enter her own home at times, and you can feel how a child’s world shrinks to whatever space is least unsafe.

The abuse escalates, and she states that it began when she was seven and that forced intercourse began when she was eleven.

Then the memoir shows how trauma creates “aftershocks,” including other predatory encounters and the chaos of adolescence. She describes an incident involving Phil that ends in court, where she notes he was found guilty and received a suspended sentence, which underlines how even “wins” can feel thin. She also describes the shattering twist of learning that the man abusing her was her biological father, and that a teenage relationship she had was therefore incestuous, calling Steve “the brother I never knew I had.” By that stage, I Did Tell, I Did is no longer just about what was done to her, but about what reality itself becomes when adults construct the lie around you.

If you’re wondering why survivors sometimes seem “inconsistent” or “contradictory,” the memoir answers that with lived logic: a child will do anything that keeps the day survivable.

That sets up the adult arc, where survival strategies become addictions, relationship patterns, and grief that doesn’t know where to go.

3.1. Adult life, motherhood, outcome

In adulthood, Harte shows the long-term cost of childhood sexual abuse as a chain reaction—mental health, dependence, intimacy, and identity.

She describes marriage, motherhood, and the way prescribed tranquillisers became part of her coping landscape, with public catalog descriptions also emphasizing prolonged dependence on prescribed medication across adult years.

She also describes how the need for love and safety collides with shame and hypervigilance, making “normal” relationships feel unreal. The memoir keeps returning to a painful paradox: she wants closeness, but closeness is where danger used to live.

One of the most heartbreaking sections centers on pregnancy and adoption, and she records the date of her son Jack’s birth as 6 July. She describes visiting the foster home and seeing the pram and baby items, a scene written with the stunned tenderness of someone watching their own life walk away.

Later, I Did Tell, I Did shows that reunion does not automatically equal healing, and she describes Jack ultimately saying he does not want further contact.

In contrast, her relationship with Peter is framed as a turning point because she decides to disclose fully and is met with steadiness rather than punishment.

The final movement is not a courtroom climax, but something more realistic: complicated closure, private reckonings, and the slow acceptance that you may never get the apology you deserved. She revisits the history with Gwen and insists on telling the full truth—“And this time I told!”—which reads like a reclaiming of voice rather than a neat resolution. She then describes her mother’s death and funeral, and how she finally feels a kind of release, writing, “I could go back to being happy, and I could let it all go.” It’s not a fair ending, but it’s emotionally believable. And that honesty is part of why the book lands.

Highlights (main events and dates): The memoir anchors key moments in time, including “back in 1971” as context for her mother’s situation and 6 July as Jack’s birthdate. Major turning points include the failed disclosure (“time for you to go”), the escalation by age eleven, the Phil court case outcome, the revelation about her biological father, and the later decision to tell her story fully to Peter and to Gwen.

Now that you know what happens, the real question is whether the book earns its claims and what it contributes beyond pain.

4. I Did Tell, I Did analysis

As memoir, Harte’s “evidence” is not studies or citations, but the consistency of lived experience across scenes, relationships, and consequences.

She explicitly flags that identifying details have been altered, which is a standard protective choice in trauma memoir, not a weakness. The argument is supported through pattern rather than proof: grooming, isolation, disbelief, and the long tail of coping. And because she includes humiliation, ambivalence, and “messy” outcomes (like the complicated adoption story), it avoids the polished “inspirational” arc that can feel dishonest.

Does it fulfill its purpose. Yes, because it shows exactly what the dedication promises: why children get too scared to tell, and what happens when they do.

The memoir also sits cleanly inside what research says about disclosure: children often disclose indirectly or repeatedly, and negative reactions can be common.

5. Strengths and weaknesses

The biggest strength is how I Did Tell, I Did makes grooming legible without turning the survivor into a lesson plan.

The biggest weakness is that readers looking for institutional detail—police procedure, safeguarding systems, timelines of official intervention—will find the focus stays primarily inside the home and the body.

What I found most compelling is the way Harte refuses to soften the maternal betrayal, because for many survivors that is the core wound.

The scenes are written with sensory clarity, like the mother-and-abuser kiss that lands as a private “verdict” on the child’s worth. The most innovative element is not language, but structure: the story repeatedly shows how trauma returns through new channels—relationships, medication dependence, fear—until truth is spoken in a context that can hold it. Still, there are moments where you may want more external anchoring, simply because the events are so severe that readers naturally reach for “how could this be allowed,” and the memoir answers that mostly through emotion rather than systems analysis.

When it does move toward closure, it’s refreshingly unsentimental: “I could go back to being happy” is not triumph, it’s survival finally unclenching.

So my overall experience is that it’s devastating, but it also teaches in a blunt, usable way—especially for anyone trying to understand why “just tell someone” is not simple.

6. Reception, criticism, and influence

Reader reception is strong on mainstream platforms, with Goodreads listing an average rating around 4.24 with over 1,000 ratings (counts change over time). A UK library catalog entry also shows high user ratings in its local system, though that’s a smaller sample.

Influence-wise, I Did Tell, I Did’s themes track closely with what child-protection organizations keep repeating: abuse is widespread, disclosure is hard, and responses from adults shape outcomes.

In England and Wales specifically, the scale is large enough that books like this function as public understanding tools, not just personal stories, given the ONS prevalence estimates.

7. Comparison with similar works and related reading on probinism.com

If you’ve read A Child Called It, you’ll recognize the blunt portrayal of a parent as the primary source of danger, but Harte’s memoir is more centered on sexual grooming within a family-adjacent relationship than on starvation and physical cruelty as the main axis.

If you’ve read Tara Westover’s Educated, the shared tissue is how loyalty and fear distort reality, although Harte’s book is less about institutions like school as escape and more about the intimate mechanics of coercion. And if you’ve read Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, you’ll see a similar refusal to romanticize motherhood when motherhood is weaponized.

On probinism.com, I already have thematically adjacent material that can pair well with this review, including a post summarizing Virginia Giuffre’s Nobody’s Girl (grooming, exploitation networks, and the social systems that enable abuse), plus a review of Educated (family control, trauma, and identity).

8. Conclusion and recommendation

I recommend I Did Tell, I Did to readers looking for a child sexual abuse memoir that is direct about grooming, blunt about betrayal, and honest about adulthood not magically “fixing” anything.

It is especially useful for survivors who want language for what happened, and for partners, parents, teachers, and clinicians who need to understand how a child can tell the truth and still be trapped.