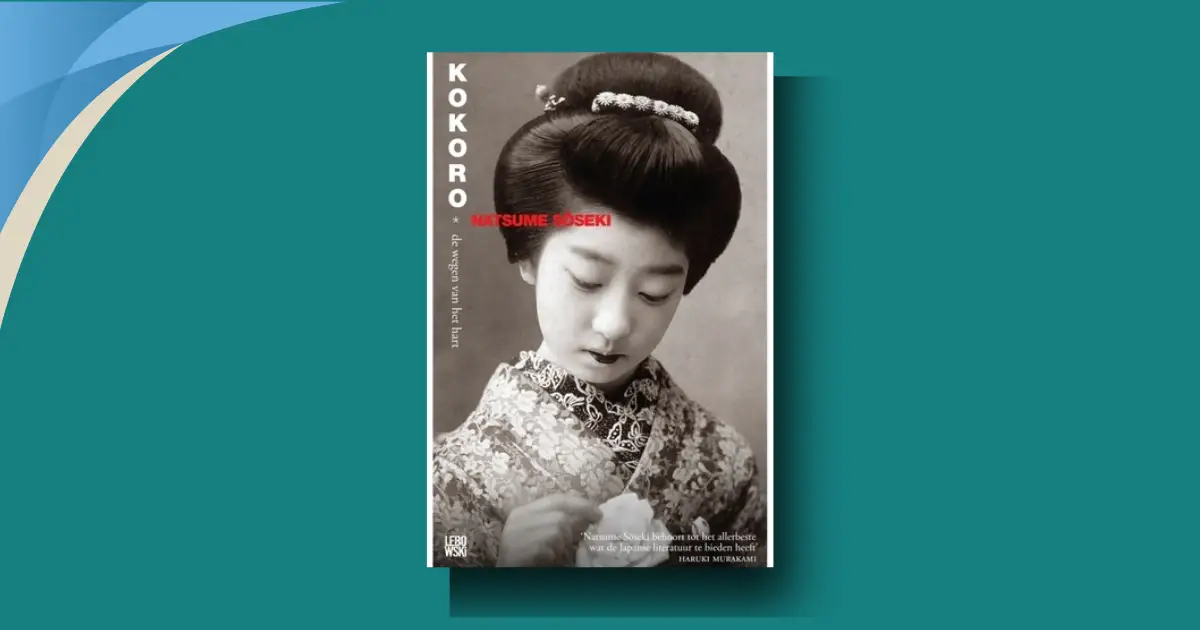

If you’re searching for a timeless Japanese novel that delves into the depths of human emotion, Kokoro by Natsume Sōseki stands as an enduring masterpiece.

Often hailed as one of the best Japanese books of all time, this 1914 classic explores themes of isolation, guilt, and the clash between tradition and modernity in Meiji-era Japan. In this in-depth Kokoro review, I’ll cover everything from a summary to a detailed analysis, character breakdowns, and its relevance in 2025. Whether you’re a fan of literary fiction, seeking Natsume Sōseki books recommendations, or curious about Kokoro themes, this guide will provide valuable insights.

Published over a century ago, Kokoro (meaning “heart” or “the heart of things” in Japanese) continues to resonate with readers worldwide.

It’s one of Japan’s best-selling novels, alongside Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human, and has been translated into multiple languages, including notable English versions by Edwin McClellan and Meredith McKinney. As we revisit it in 2025, amid a world grappling with mental health and social disconnection, Kokoro feels more pertinent than ever.

Let’s dive into why this book remains a cornerstone of modern Japanese literature.

Table of Contents

Natsume Sōseki: The Author Behind the Masterpiece

Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), born Natsume Kinnosuke, is widely regarded as one of Japan’s foremost novelists of the Meiji era (1868–1912). His life bridged the traditional and modern worlds, much like the themes in his works.

Sōseki graduated from Tokyo University in 1893 with a degree in English literature and taught high school before traveling to England on a government scholarship. This experience profoundly influenced him, exposing him to Western individualism while deepening his appreciation—and critique—of Japanese traditions.

Upon returning, Sōseki lectured at Tokyo University and began his writing career with satirical novels like I Am a Cat (1905) and Botchan (1906).

He produced 14 novels, haiku, Chinese-style poems, essays, and literary theory papers. Kokoro, his final completed novel, forms the last part of a trilogy following To the Spring Equinox and Beyond (1912) and The Wayfarer (1912). Sōseki’s works often grapple with alienation, a theme rooted in his own struggles with health issues and cultural dislocation.

In 2025, Sōseki’s legacy endures. His portrait once graced Japan’s 1,000-yen banknote, symbolizing his cultural impact. For readers exploring Natsume Sōseki biography, Kokoro exemplifies his shift from humor to profound psychological introspection.

Publication History and Background of Kokoro

Kokoro was first serialized in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper from April 20 to August 11, 1914, under the title Kokoro: Sensei no Isho (“Kokoro: Sensei’s Testament”). Later published as a book by Iwanami Shoten, the title was shortened, and the kanji for “kokoro” (心) changed to hiragana (こころ) for accessibility.

Sōseki originally planned Kokoro as a collection of short stories, but the core narrative—”Sensei’s Testament”—grew into a three-part novel. Set during the Meiji era’s end, it reflects Japan’s rapid modernization and the emotional toll on individuals. The novel’s title evokes multiple meanings: heart, spirit, affection, resolve, or courage—capturing the story’s emotional core.

By 2025, Kokoro has sold millions in Japan, with over 7 million copies of the Shincho Bunko edition alone. It’s a staple in school curricula and has inspired adaptations, solidifying its status as essential Japanese literature classics.

Kokoro Plot Summary

Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki is a profound Japanese novel exploring themes of isolation, guilt, betrayal, and the tension between tradition and modernity during the Meiji era.

The story is told retrospectively by an unnamed young narrator and is divided into three parts: “Sensei and I,” “My Parents and I,” and “Sensei’s Testament.”

The narrative builds slowly, focusing on introspection and emotional depth rather than action. Below is a complete, detailed retelling of the plot.

Part I: Sensei and I

The story begins with the unnamed narrator, a young university student, on summer vacation in Kamakura near Tokyo. While swimming at the beach, he notices an older, enigmatic man accompanied by a Westerner.

Intrigued by the man’s aloof demeanor, the narrator strikes up a conversation after the Westerner leaves. They bond over swims, and the narrator starts calling him “Sensei” (meaning “teacher” or “master”), though Sensei shows little enthusiasm for their growing friendship.

Sensei warns the narrator that getting too close will lead to disappointment, hinting at his own self-loathing and unsuitability as a friend.

Back in Tokyo after vacation, the narrator visits Sensei’s home unannounced but finds him absent.

On a second visit, he meets Sensei’s kind wife, Shizu (referred to as “Okusan” or “the lady” in some contexts), who reveals that Sensei visits a friend’s grave in Zōshigaya Cemetery every month. This piques the narrator’s curiosity about Sensei’s mysterious past.

Over the following months and years, the narrator becomes a regular visitor, growing close to the couple.

Sensei remains distant, refusing to discuss his deceased friend or explain his reclusive, unemployed lifestyle. He philosophizes about loneliness, love, and human flaws, cautioning the narrator that admiration often turns to disdain.

Despite this, Sensei promises to one day reveal his full story when the time is right.

During this period, the narrator briefly returns home to his rural family, where his father is suffering from kidney disease.

He plays chess with his father but feels disconnected and bored, realizing his emotional allegiance lies more with Sensei.

Back in Tokyo, the narrator discusses inheritance with Sensei, who shares a vague story of being cheated by relatives after his parents’ death, advising the narrator to secure his own affairs.

The narrator presses for more details about Sensei’s life, but Sensei deflects, saying the revelation will come later.

After graduating, the narrator celebrates with Sensei and Shizu, then heads home for summer, feeling guilty about his ambivalence toward his father’s impending death. Throughout this part, the narrator idolizes Sensei’s wisdom but senses a deep, unspoken sorrow.

Part II: My Parents and I

The narrator returns to his provincial hometown, where his father’s health has stabilized temporarily, but their worldviews clash.

The narrator finds his parents’ naive, traditional attitudes irritating and feels out of place. Plans for a graduation celebration are postponed when Emperor Meiji falls ill and dies in July 1912, an event that deeply affects the family and symbolizes the end of an era. The narrator’s mother urges him to find a job in Tokyo to ease his father’s worries, but the father’s condition deteriorates rapidly—he becomes bedridden, loses vigor, and suffers delusions.

Desperate for advice, the narrator writes to Sensei requesting help finding employment, but receives no reply for months.

In September, the narrator plans to return to Tokyo but delays after his father faints. His elder brother and brother-in-law arrive to assist with caregiving as the father grows increasingly frail and incoherent.

The family is shocked by news of General Nogi’s junshi (ritual suicide to follow his emperor in death), which prompts reflections on loyalty and tradition.

Amid this, a cryptic telegram from Sensei arrives, summoning the narrator to Tokyo immediately.

Unable to leave his dying father, the narrator declines by telegram and letter, explaining his situation. Days later, a thick, registered letter from Sensei arrives.

Sneaking away from his father’s bedside, the narrator opens it and skims to the end, discovering a chilling line: “By the time this letter reaches you, I’ll be gone from this world. I’ll have already passed away.”

Realizing Sensei intends suicide, the narrator rushes to the station, abandons his family, and boards the first train to Tokyo. En route, he reads Sensei’s letter in full, which forms the novel’s third part.

Part III: Sensei’s Testament

Sensei’s lengthy confessional letter, written as a “testament,” reveals his entire life story, explaining his reclusiveness and decision to die. He instructs the narrator to keep it secret until after Shizu’s death, as he cannot bear to burden her with the truth.

Sensei hopes his story will serve as a cautionary tale for the young man.

Sensei grew up in a rural area as an only child. His parents died of illness when he was a teenager, leaving him a substantial inheritance managed by his uncle during his university studies in Tokyo.

Each summer, Sensei returned home, where his uncle pressured him to marry and settle down, but Sensei declined. Eventually, he discovered his uncle had embezzled most of his fortune through failing businesses. Devastated and distrustful, Sensei salvaged what remained, sold his family home, visited his parents’ graves one last time, and cut all ties with his relatives, fostering a deep cynicism toward humanity.

Back in Tokyo, Sensei left his rowdy student lodgings for quieter quarters, boarding with a widow (Okusan) and her beautiful daughter, Ojosan (who is Shizu).

He falls instantly in love with Ojosan but hesitates due to his uncle’s betrayal, suspecting ulterior motives. Okusan treats him like family and subtly encourages a match.

Meanwhile, Sensei’s university friend K—a passionate, ascetic student disowned by his adoptive family for pursuing philosophy and religion instead of medicine—struggles financially and becomes withdrawn.

Feeling obligated, Sensei invites K to board with them, hoping the stable environment will help K’s “spiritual betterment.”

K adapts well, becoming more sociable, but also falls in love with Ojosan. During a walking tour on the Bōshū Peninsula, Sensei grows tormented by jealousy, suspecting mutual affection between K and Ojosan.

Back home, K confesses his love to Sensei, torn between his spiritual ideals and newfound passion. Sensei, hiding his own feelings, manipulates K by reminding him of his vows of discipline, shaming him for hypocrisy.

Fearing K will propose first, Sensei secretly asks Okusan for Ojosan’s hand; she and Ojosan accept joyfully. K learns from Okusan and withdraws into silence. That night, K commits suicide by slashing his throat, leaving a brief note: “Why did I wait so long to die?” Sensei is wracked with guilt, realizing his betrayal makes him no better than his uncle—he prioritized self-interest over friendship.

Sensei notifies K’s family, arranges his burial at Zōshigaya Cemetery (explaining the monthly visits), and relocates with Okusan and Ojosan.

He marries Ojosan six months later but remains haunted, unable to confess. Their marriage suffers; Sensei withdraws into idleness, reading, and drinking, losing faith in himself and humanity. Okusan dies, leaving Ojosan (Shizu) alone with him.

Sensei resolves to be a better husband but frequently contemplates suicide, held back only by concern for her.

Emperor Meiji’s death in 1912 convinces him he’s a relic of the era, outliving his time. Inspired by General Nogi’s junshi, Sensei decides to end his life, viewing it as atonement for K’s death—not just from lost love, but from profound alienation and self-disappointment.

He writes the testament to fulfill his promise to the narrator, hoping it prevents similar mistakes.

Ending and Resolution

The novel concludes with the narrator arriving in Tokyo too late—Sensei has already committed suicide, fulfilling his plan.

The narrator is left to reflect on Sensei’s tragic life, the weight of betrayal, and the inescapable loneliness of modern existence.

He grapples with his own choices, including abandoning his dying father, and inherits Sensei’s story as a burdensome legacy. The book ends on a somber note, emphasizing how guilt and isolation persist across generations, with no neat resolution.

Kokoro Themes in Kokoro: Isolation, Guilt, and Modernity

Kokoro masterfully weaves themes that define modern existence. Central is isolation (kodoku), not just physical but philosophical.

Sensei embodies this, withdrawing after K’s death, believing “loneliness is the price we have to pay for being born in this modern age.” Scholar Edwin McClellan argues psychological guilt is secondary to this isolation, tracing it through Sōseki’s works.

Guilt and betrayal drive the plot. Sensei’s betrayal of K leads to lifelong penitence—monthly graveside visits, refusal of happiness. He views suicide as atonement, aligning with Confucian ideals of responsibility. As he writes, he feels punished by heaven.

The clash between tradition and modernity reflects Meiji Japan’s Westernization. Sensei, influenced by both, feels alienated. Jun Etō links this to Sōseki’s London crisis, where Western individualism shattered his Confucian roots.

Emperor Meiji’s death symbolizes this era’s end; Sensei’s suicide follows Nogi’s junshi, a traditional act in a modern context.

Takeo Doi offers a psychological reading, seeing Sensei’s paranoia as schizophrenic delusions, culminating in homoerotic loyalty to K. Meredith McKinney notes the “intellectually erotic” bonds among men.

In 2025 reviews, themes resonate with post-pandemic isolation. One calls it a “haunting tale of loneliness,” another praises its “relentless examination of duty.” Kokoro themes analysis reveals its timeless critique of egoism and human frailty.

Kokoro Analysis: Depth and Complexity

The unnamed narrator represents youth’s idealism. His admiration for Sensei evolves into disillusionment, mirroring generational shifts. He abandons his dying father for the dead Sensei, symbolizing “father transference.”

Sensei is the tragic core—a man of intellect haunted by past actions. His letter reveals vulnerability: “I have nobody but you.” Excerpts show his torment, like warning the narrator against intimacy.

K embodies spiritual purity, torn between ideals and passion. His suicide stems from alienation, not just lost love.

Secondary characters like Sensei’s wife and the narrator’s father highlight contrasts—loyalty vs. egoism, tradition vs. progress.

Sōseki’s characters aren’t heroic; they’re flawed, making Kokoro character analysis a study in human imperfection.

Literary Style: Subtlety and Psychological Depth

Sōseki’s prose is understated, relying on introspection over drama. The three-part structure builds tension, with Sensei’s letter as a confessional climax. Symbolism abounds: gravesites for guilt, the sea for isolation.

In McKinney’s translation, the language flows poetically, capturing nuances like “mono no aware” (pathos of things). A 2025 review lauds its “quiet, devastating” impact. For Kokoro literary style, it’s a masterclass in restraint.

Cultural and Historical Context

Set at Meiji’s end, Kokoro critiques Japan’s Westernization. Emperor Meiji’s death (1912) marks tradition’s decline; Nogi’s junshi evokes samurai loyalty amid industrialization.

Sōseki, having studied in England, infuses personal conflict. The novel questions individualism’s cost, resonating in 2025’s globalized world.

Translations and Adaptations

English translations include Ineko Kondo (1941), McClellan (1957), and McKinney (2010). McKinney’s is praised for evoking “intellectually erotic” tensions.

Adaptations: Films by Kon Ichikawa (1955) and Kaneto Shindō (1973); TV series; anime (Aoi Bungaku); manga. A comic satire in Step Aside Pops (Kate Beaton) shows its pop culture reach.

Kokoro Quotes

On Loneliness and the Modern Era

- Sensei to the narrator (Chapter 13, Page 36):

“I’m a lonely man… I’m lonely, but I’m guessing you may be a lonely man yourself. I’m older, so I can withstand loneliness without needing to take action, but for you it’s different—you’re young.” - Sensei (Chapter 13, Page 36):

“No time is as lonely as youth. Why else should you visit me so often?” - Sensei (Chapter 14, Page 50):

“We who are born into this age of freedom and independence and the self must undergo this loneliness. It’s the price we pay for these times of ours.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 238):

“Eventually, I began to wonder whether it was not the same unbearable loneliness that I now felt that had brought K to his decision.”

On Passion and Love

- Sensei (Chapter 14, Page 49):

“You’re being carried along by passion. Once the fever passes, you’ll feel disillusioned.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 199):

“It seems to me that this kind of jealousy is perhaps a necessary part of love.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 199):

“I no longer feel that early fierce passion of love.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 206):

“Why had his passion reached such a pitch that he felt he must confess it to me?” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 217):

“No matter how fierce was the passion that gripped him, the fact is he was paralyzed, transfixed by the contemplation of his own past.”

On Self-Reflection and Guilt

- Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 236):

“Others were already repulsive to me, and now I was repulsive even to myself.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 153):

“Perhaps because these guilty thoughts had robbed me of a natural response…”

On Revealing One’s Heart and Legacy

- Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 136):

“Now I will wrench open my heart and pour its blood over you. I will be satisfied if, when my own heart has ceased to beat, your breast houses new life.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 244):

“My past, which made me what I am, is an aspect of human experience that only I can describe. My effort to write as honestly as possible will not be in vain, I feel, since it will help both you and others who read it to understand humanity better.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 244):

“My aim has been to present both the good and bad in my life, for others to learn from.” - Sensei (Sensei’s Testament, Page 244):

“I want her told nothing. My one request is that her memory of my life be preserved as untarnished as possible.”

Modern Relevance and 2025 Reviews

In 2025, Kokoro speaks to mental health crises. Reviews highlight loneliness: “A slow exploration of isolation and depression.” Another: “Thought-provoking… explores the essence of loneliness.” Goodreads users rate it 4.05/5, praising its emotional depth.

Comparisons to Murakami or Dazai underscore its influence. As one analysis notes, it’s about “the virtue of melancholy.”

Reading Kokoro in 2025, I was struck by its quiet power. Sensei’s guilt mirrors modern regrets; the narrator’s indecision echoes millennial anxieties. Excerpts like “If you were suddenly to die, could Sensei go on living?” (Chapter 17) probe love’s fragility.

It’s not uplifting but cathartic—a reminder that isolation is universal. Rating: 4.8/5. Essential for best Japanese novels lists.

Conclusion

Kokoro is more than a novel—it’s a mirror to the soul. For Kokoro book review 2025, it earns top marks for depth and relevance. Dive into this classic; its heart will linger.