What does it mean to be truly unstoppable? Is it a quality reserved for mythic heroes and legendary figures, or can it be found in the most unassuming among us? Manjhi The Mountain Man, directed by the visionary Ketan Mehta, answers this question not with grand special effects or hyperbolic dialogue, but with the relentless, heart-wrenching, and ultimately triumphant true story of one man’s defiance against nature and apathy.

This 2015 biographical film is more than a cinematic experience; it is a profound meditation on love, loss, and the sheer, unadulterated power of human resolve. From the moment I began watching, I was not merely a viewer but a witness to a testament of spirit that left an indelible mark on my perception of struggle and achievement.

The film transforms the legend of Dashrath Manjhi from a folk tale into a palpable, emotionally charged reality, making it one of the most significant and moving Indian biopics of the last decade.

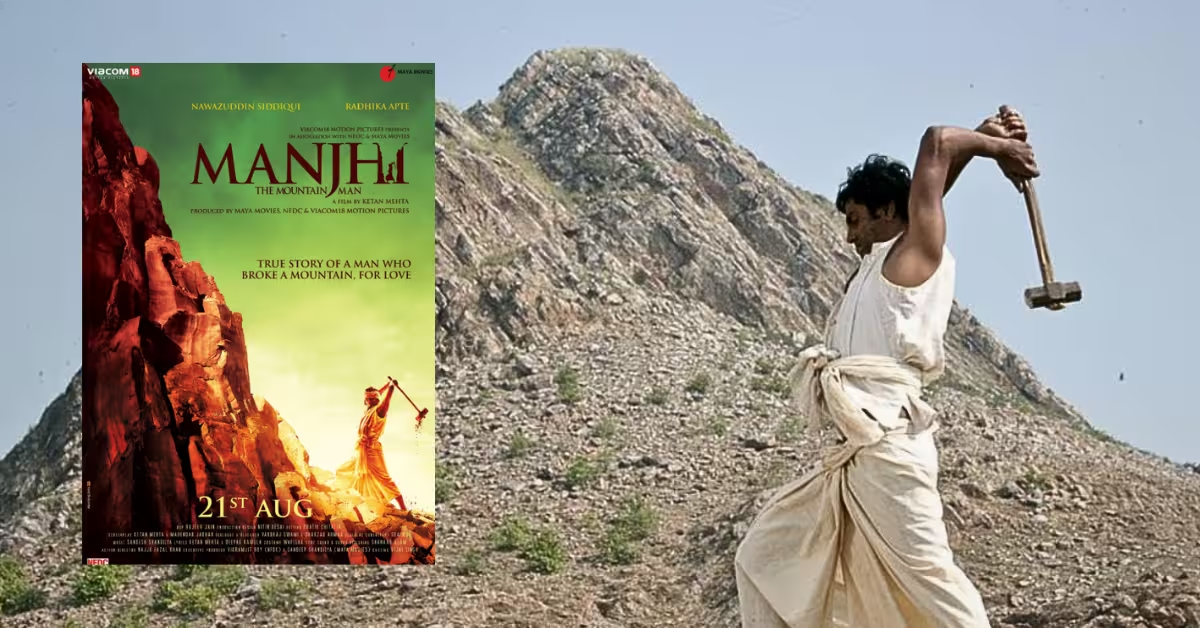

Starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Radhika Apte, the film premiered on 21 August 2015, runs on the fuel of grief turned into purpose, and closes with the humble revelation that sometimes history is written not in ink but in blisters.

The film’s subject is extraordinary; the cinema around him is passionate, flawed, and frequently stirring—an affecting movie review subject if you love human-scale epics. Basic production facts (director, cast, release date) and public reception figures in this film analysis draw on published summaries and reviews.

Table of Contents

Plot Summary

Set against the harsh, sun-baked landscape of 1960s Bihar, Manjhi The Mountain Man introduces us to Dashrath Manjhi (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), a landless labourer from Gehlaur village, whose life is defined by the gruelling daily struggle for survival. The narrative’s heart lies with his deep, tender love for his wife, Phaguniya (Radhika Apte). Their relationship is portrayed not with grand romantic gestures, but through quiet moments of shared hardship and unwavering support, making its foundation feel authentic and strong.

The central conflict of the film, and of Manjhi’s life, is a formidable mountain that separates his village from the town of Wazirganj. This geological monolith is not just a physical barrier; it is a symbol of systemic neglect, social inequality, and the fatal distance between poverty and basic necessities like healthcare, education, and opportunity. The villagers are forced to undertake a perilous and time-consuming journey around it for every essential need.

The catalyst for the extraordinary saga that follows is a moment of devastating tragedy. Phaguniya, pregnant and in need of help, attempts to cross the mountain and suffers a terrible fall.

Because the nearest hospital is an impossible 55 kilometers away due to the mountain’s obstruction, she succumbs to her injuries, leaving Dashrath shattered. In his profound grief, a seed of mad, revolutionary resolve is planted. He makes a vow that seems delusional to everyone around him: he will single-handedly carve a road through the mountain so that no one else in his village would ever have to suffer the same fate.

What follows is a 22-year odyssey of back-breaking labour. Armed with nothing but a hammer, a chisel, and an iron will, Manjhi begins his quixotic task.

The film meticulously chronicles this journey, showing him being ridiculed as a “lunatic” by his own community, facing ostracization, and battling starvation, exhaustion, and the sheer physical impossibility of his mission. He endures the cyclical cruelty of nature, working through blistering summers and drenching monsoons.

He faces opposition from a cynical and exploitative village landlord (Tigmanshu Dhulia) who sees Manjhi’s act of defiance as a threat to the established social order.

The narrative doesn’t shy away from the personal cost of his obsession. We see his relationship with his daughter strain, his body age prematurely, and his spirit be tested to its absolute limit.

Yet, through it all, the memory of Phaguniya and the faces of his fellow villagers fuel his determination. The film’s most powerful moments are often silent, focusing on the rhythmic, metronomic clang of hammer on chisel, a sound that becomes the score of his life—a persistent beat against the silence of indifference.

Manjhi’s body is a ledger of the years. Fingers split and heal; shoulders knot; knees buckle. But the grooves in the rock are deeper, long cuts that gradually stitch into a corridor. The film insists on the arithmetic: he is carving a path roughly 30 feet wide and about 360 feet long, chipping through rises that drop 25 feet in places (the film’s epilogue distills these measurements, linking labor to tangible result).

The long project—22 years of it—presses the story toward allegory. A dozen monsoons later, villagers begin to use the widening cut to ferry the sick and the elderly.

By then, the ridicule has stalled; practical gratitude takes its place. Manjhi’s “madness” passes a checksum in the collective mind: it works. (These core facts about scale and duration are part of the public record and appear in standard references on the film and its subject. )

After decades of solitude and struggle, a shift occurs. The very people who mocked him begin to see the tangible progress. The mountain is being conquered. The film beautifully captures this transition from ridicule to reverence, culminating in a community that finally rallies behind its once-mad prophet. The final act is one of cathartic victory. Manjhi The Mountain Man shows us the moment he breaks through, creating a path 360 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 25 feet deep—a monument not of stone, but of love.

The film’s poignant epilogue reveals that it took the government 52 years after he started and 4 years after his death in 2011 to finally pave a proper road to Gehlaur, a stark reminder that while one man can move a mountain, moving a bureaucracy is often a far more Herculean task.

Manjhi The Mountain Man ends without sermonizing. A life has been spent, and a geography has changed. In my movie review, that is the victory the film refuses to vulgarize. The mountain is smaller now; the love is not.

Analysis

1. Direction and Cinematography

Ketan Mehta directs the film as a humanist parable with mud on its shoes. He avoids miracle staging; there is nothing miraculous about repetitive labor, and the film wisely resists turning chiseling into spectacle. Instead, Mehta leans on the poetry of routine—of tools lifted and lowered, of sweat beading and dust sticking.

That decision gives this its spine: we watch a man flirt with futility and then teach futility to sit.

Cinematographer Rajiv Jain photographs the landscape as both antagonist and altar. Close-ups live in a tight palette of earth tones; wides stretch to heat-shimmer horizons. The camera favors hand-held intimacy in domestic scenes and sturdy, horizon-level frames against the mountain—man as a vertical stroke against a horizontal sentence. Sunlight is a motif: dawns soft, noons punishing, dusks forgiving. When monsoon arrives, the rock bleeds darker.

2. Acting Performances

Nawazuddin Siddiqui renders Dashrath Manjhi with that particular Nawazuddin sorcery: a small man who expands to fill a frame.

His gait is anxious early on, then deliberate; his eyes carry mischief when Phaguniya is alive, then narrow into long-distance focus after. Grief is in his jaw; hope is in his knuckles. If this movie review repeats admiration, it’s because the performance earns it. Radhika Apte gives Phaguniya warmth and wit; she is not just a muse but a co-author of Manjhi’s purpose. Tigmanshu Dhulia and Pankaj Tripathi leave sharp fingerprints as landlord and son, personifying the laziness of inherited power.

Supporting turns (Gaurav Dwivedi as the journalist, others around the village) play mostly as conscience-bearing observers. Cast information is consistent with published listings.

3. Script and Dialogue

The screenplay (credited to Ketan Mehta, Anjum Rajabali, Mahendra Jhakar, Varadraj Swami, Shahzad Ahemad) is lean in vocabulary and heavy in ritual. That suits the premise. Repetition becomes the text: the same resolve re-spoken ten thousand times. When melodrama appears, it’s in the villagers’ chorus or in a politician’s flourish, not in Manjhi himself.

Pacing occasionally sags in the mid-sections—an almost inevitable risk in a film whose arc is measured in decades—yet the structure anchors us with flashbacks that refill the emotional well. (Writer credits: )

For purists, the dialogue walks the fine line between colloquial grit and aphoristic punch. There are slogans you can carve on a wall and grins that carry a line’s weight without words. The verdict: the script’s simplicity is a feature, not a flaw; it lets the mountain do the talking.

4) Music and Sound Design

The score splits duties between Sandesh Shandilya and Hitesh Sonik, with songs like “Gehlore Ki Goriya,” “O Rahi,” and “Dum Kham.” The music understands loneliness: sparse instrumentation, percussive cues that rhyme with hammer-on-rock, and folk-tinged melodies that feel at home in the dust. Sound design emphasizes tactility—metal biting stone, grit underfoot, rain drumming on bare back. This is not a wall-to-wall score; silence earns as much screen time as strings.

For Manjhi movie review readers, note that the soundtrack released 9 August 2015 under Zee Music Company, with a total listed length of about eleven minutes across principal tracks.

5. Themes and Messages

Grief as architecture. The film argues that sorrow can be direction, not just weight.

Love as infrastructure. Phaguniya doesn’t vanish; she reappears as purpose.

Caste and neglect. The mountain stands in for bureaucracy, extractive feudalism, and the casual cruelty of distance.

Public recognition vs. public good. The timeline—decades to cut, years to pave—reads as commentary on how institutions ratify what citizens already solved.

In my film analysis, the most resonant message is painfully current: access is policy. A one-man road is not a miracle; it’s a verdict on what the state failed to deliver. The lens catches hope shining through the crack.

Comparison

Within Indian biopics, Manjhi The Mountain Man sits between the athletic mythmaking of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag and the insurgent realism of Paan Singh Tomar. It doesn’t chase kinetic montage or gun-barrel tension; it pursues endurance.

Compared to international “lone-against-the-world” dramas (The Pianist, 127 Hours, Cast Away), this story is less about survival in extremis and more about ordinary extremity—grief in a village, chiseling in a field. For movie review purposes, what sets it apart is scale: a project so slow that cinema has to learn patience to depict it.

Audience Appeal & Reception

Who will love it?

- Viewers drawn to character-first stories; those who favor of social context; students of development and public policy; admirers of Nawazuddin Siddiqui.

Who might bounce?

- Viewers expecting constant plot “events” may find the middle stretch slow; those allergic to earnestness may wish for more irony.

Reception snapshot:

- Hindustan Times called it “an inspiring, touching tale of a common man,” rating it 4.5/5; NDTV gave 3/5; Times of India 3/5; Bollywood Hungama 2.5/5; Indian Express 2/5. The film’s estimated box office is around ₹18 crore. It was declared tax-free in Bihar prior to release, and an early leak of a preview copy prompted a cyber-police case—facts that colored its commercial arc. (Reception, figures, and notes as compiled in standard references on the film. )

Awards:: Major national awards aren’t prominently listed in common summaries. The state tax-free status functioned as a form of governmental recognition, signaling cultural value even as the film’s award shelf remained modest.

Personal Insight: Why Manjhi Matters Now

I watched Manjhi The Mountain Man with that familiar ache: the sense that the hardest problems in our neighborhoods do not announce themselves as crises; they accumulate as distances. A school two hills away becomes a dropout; a clinic across a ridge becomes a funeral. In my personal movie review, Manjhi’s hammer isn’t just grief management; it’s civic imagination.

Watching Manjhi The Mountain Man in today’s world feels more relevant than ever. We live in an age of instant gratification, where obstacles are expected to be solved with a quick fix, a new app, or a viral tweet. Dashrath Manjhi’s story is a stark, beautiful antithesis to this. His life is a lesson in the profound power of delayed gratification and unwavering focus. His mountain was literal, but ours are metaphorical: procrastination, self-doubt, societal pressures, the overwhelming scale of global problems.

Manjhi’s tale teaches us that change is never instantaneous. It is the cumulative result of showing up every day, even when no one is watching, even when everyone is laughing. It’s about chipping away, bit by bit, at the things that separate us from a better world—whether that’s personal improvement, professional goals, or social change. In a society that often celebrates the loudest voice in the room, Manjhi’s story is a quiet reminder that the most powerful force can be the consistent, silent, relentless application of will.

He didn’t wait for permission, resources, or a committee meeting. He saw a problem and, with the tools he had, began to solve it. That is perhaps the most vital lesson for our time: to start chipping away at our own mountains, however insurmountable they may seem.

Today’s language for change is crowded with frameworks: design thinking, public–private partnerships, smart cities. They matter. But the film shaves the jargon down to one proposition: identify the friction that steals dignity and remove it, blow by blow if you must.

The lesson isn’t that we should literally take up hammers; it’s that we should locate the mountain in our context—an inaccessible legal aid center, a digital divide, a predatory landlord, a broken road—and then choose persistence over spectacle.

The movie also challenges our dopamine economy. I think of how often I seek progress I can screenshot. Manjhi works for 22 years without a like, a retweet, or a viral arc. He is not “building an audience.” He is building a road. The film invites a different scoreboard: did someone get to the hospital faster? Did the pregnant woman make it over safely? If “impact evaluation” sounds too clinical, Manjhi translates it into a single question: who crossed because you tried?

There’s a tenderness in how the story refuses cynicism. When the paved road arrives after his death, I felt rage—and then recognition. Sometimes outcomes are delayed beyond the lifespan of their authors. In a contemporary setting—climate adaptation, sanitation, public transit—that’s the reality. You might start a thing that another handsomely ribbon-cuts. If that prospect robs you of motivation, Manjhi suggests you were in it for the wrong parade.

Finally, there is the love story. Not just husband and wife, but citizen and place. Love of land is often manipulated for politics; here, it is re-imagined as maintenance. Loving where you live means refusing to let a mountain—literal or structural—decide your child’s odds.

If I had to compress this movie review into a practice: keep a small hammer at the desk, metaphorical or otherwise. Ask each morning, what stone can I chip today? The answer is rarely glamorous. The road is still the road.

Pros and Cons

Pros

- Stunning location work and elemental visuals

- Gripping central performance by Nawazuddin Siddiqui

- Emotionally coherent arc from grief to purpose

- Sound design that honors silence and tactility

- A thematically rich film analysis playground (caste, state, access)

Cons

- Slow pacing in parts, especially mid-section

- Occasional melodramatic flourishes around secondary characters

- Expository political scenes that feel schematic

Conclusion

As a movie review subject, Manjhi The Mountain Man carries a simple dare: sit with a human being as he converts loss into infrastructure. Ketan Mehta’s biopic is not flawless—few are—but it is faithful to the physics of change.

One hammer tap does nothing; a hundred thousand change a map.

The performances hum with life, the craft refuses shortcuts, and the story holds a lantern to a truth we keep forgetting: dignity often begins with the shortest road to help. For cinephiles, students of development, and anyone nursing a private mountain, this recommends the journey.

Recommendation: A must-watch if you believe endurance can be cinematic.