Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History is more than a graphic novel—it’s a memory machine that solves the problem of how to tell atrocity without numbing the reader.

Spiegelman’s innovation answers a century-old dilemma: how do we carry the Holocaust into the present so people feel it, learn from it, and do not forget it, even as living witnesses fade from view.

It works by fusing a father’s meticulously narrated survival story with a son’s searching, sometimes exasperated, sometimes tender, attempt to understand trauma, inheritance, and the ethics of representation.

History textbooks often flatten horror into dates, numbers, and dull summaries—Maus I makes the Holocaust intimate, visible, and ethically complicated.

It solves the problem of “distance” by drawing it, forcing us to watch memory and meaning get argued, revised, and lived between father and son in kitchens, on stationary bikes, and in cramped Queens apartments.

It also solves the problem of denial and distortion by embedding personal evidence and intergenerational consequences into a form readers actually finish.

A son turns his father’s survival into a graphic narrative that proves memory is messy, love is hard, and history bleeds into the present whether we like it or not.

The book is a documented life-history (Vladek Spiegelman’s) serialized in the avant-garde magazine RAW and then expanded into two volumes; it earned Art Spiegelman a 1992 Pulitzer Prize Special Citation, was canonized by TIME among essential nonfiction, and—decades later—shot to #1 on Amazon when a school board tried to ban it, demonstrating both cultural impact and enduring relevance.

Best for / Not for

Best for readers who want a complete, emotionally honest understanding of the Holocaust’s facts and aftershocks, who appreciate literary nonfiction, memoir, and visual storytelling, and who are ready to see cats, mice, and pigs used to portray moral systems, power, and fear without trivializing the stakes.

Not for readers seeking escapism, simple heroes/villains, or tidy uplift—or those who prefer not to engage depictions of death, suicide, and intergenerational conflict in frank, historically precise terms.

Table of Contents

A Brief Introduction

Maus I: My Father Bleeds History (Art Spiegelman) is a landmark Holocaust graphic novel and Pulitzer-recognized work that changed how we read history, memoir, and comics, and this guide—grounded in careful reading and fresh research—offers a complete, human-voiced overview so you don’t need to go back to the book to understand its story, structure, themes, evidence, and impact.

It centers on Vladek Spiegelman’s survival in Nazi-occupied Poland and Auschwitz, told to his son Art in late-1970s New York, while also documenting the fraught father-son relationship and the ethics of turning trauma into art.

It is also a case study in why Holocaust education needs emotionally credible narratives: with approximately six million Jews murdered, and most remaining survivors in their late eighties and nineties, we urgently need forms like Maus that keep witness alive.

1. Introduction

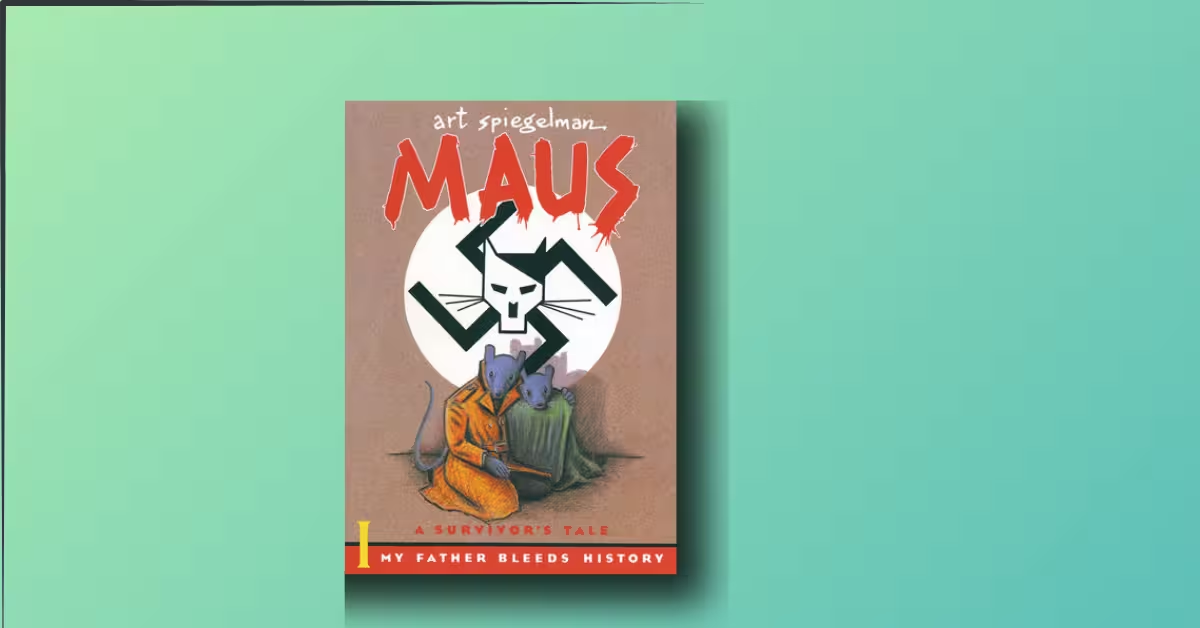

Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History by Art Spiegelman was published by Pantheon Books on August 12, 1986 (159 pp.), the first of two volumes later collected as The Complete Maus.

The book belongs to literary nonfiction and the graphic memoir; its chapters were first serialized in RAW, the avant-garde comics magazine Spiegelman edited with Françoise Mouly, before Pantheon published the collected Book I.

Spiegelman—an artist from the underground comix milieu and co-founder of RAW—would receive a 1992 Pulitzer Special Citation for Maus, a landmark in recognizing comics as serious literature.

At heart, Maus I argues two things: first, that bearing witness to the Holocaust is a moral obligation demanding formal innovation, and second, that memory’s transmission is relational and contested—an ongoing negotiation between survivor and child, evidence and imagination, love and anger.

2. Background

The Holocaust’s scope is historically uncontested: about six million Jews were murdered by the Nazi regime through gas chambers, mass shootings, deliberate starvation, and terror, with other groups (Roma, Poles, Soviet POWs, people with disabilities) also targeted.

By the 1970s and 1980s—when Art interviews Vladek and publishes Maus I—a new challenge had emerged: how to sustain accurate, affectively powerful memory as survivors aged and denialists spread misinformation; this is even more urgent today as most survivors will die within 10–15 years.

Spiegelman’s formal answer was to blend documentary testimony with a self-conscious frame narrative that lets readers watch the telling get made: tape recorders click, drawings are revised, tempers flare, and errands interrupt history; in short, the process of memory becomes part of the story.

He also uses the controversial animal allegory—Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs—not to dehumanize but to signal constructed identities, predator–prey dynamics, and the absurd racialization that underwrote Nazi ideology; the simplicity of design sharpens rather than softens horror.

The result is a hybrid text: a survivor testimony, an artist’s memoir, and a meta-history of how trauma gets archived and inherited, chapter by chapter, disagreement by disagreement, panel by panel.

3. Summary

The frame opens in Rego Park in the late 1970s, where Art (“Artie”) visits Vladek, now remarried to Mala after Anja’s suicide, and begins recording his father’s wartime story; what follows alternates between Vladek’s Poland—courtship, marriage, business, occupation, ghettoization, hiding, betrayal, and transport—and Art’s present-tense negotiations with a prickly, traumatized parent whose frugality, suspicion, and controlling habits are the sediment of survival.

Vladek’s early life, wooing Anja (intellectual, depressive, beloved), and the birth of their first son Richieu play out against a Poland tightening under antisemitic laws, surveillance, and violence; work and connections matter, luck matters more, and small choices—what to trade, whom to trust—become life and death.

As deportations accelerate, Vladek hustles “on the Aryan side” with forged papers, trading, bargaining, and hiding in attics, bunkers, and barns; the couple sends Richieu away to relatives in hopes of safety, a decision that later curdles into a grief that is both unspeakable and inescapable, shaping Anja’s lifelong depression and Vladek’s bone-deep vigilance.

Eventually, betrayals and roundups culminate in Auschwitz, the end point of Book I’s arc and the beginning of Book II’s; the last chapters compress into railroad cars and the sick recognition that “this was 1944… we knew everything… and here we were,” a line whose flat affect terrifies more than any scream.

In the New York frame, Art quarrels with Vladek over casual racism, parsimoniousness, and control (throwing out Art’s jacket; hoarding nails and food; distrusting new people), while Mala fumes about money and emotional stinginess; these small domestic abrasions are the moral fallout of systems designed to humiliate and starve.

Highlighted takeaways

- Witness, then form: The frame (1970s interviews) and the war narrative (1930s–45) are braided; this architectural choice is the argument that memory is collaborative, fallible, negotiated.

- Animal allegory is strategy, not gimmick: Mice/cats/pigs/dogs map power and ideology; the device makes readers notice how identities are forced, not chosen.

- Trauma is intergenerational: Anja’s suicide, Vladek’s controlling thrift, and Art’s guilt/impatience show how survival morphs into habits that estrange loved ones.

- Chance and cunning co-author survival: Vladek’s bargaining intellect helps, but he insists survival wasn’t proof of virtue; randomness ruled.

- Ending of Book I: The transport to Auschwitz closes the volume starkly; the “we knew everything” acknowledgment crushes the illusion of ignorance and implicates readers in the psychological weight of foreknowledge.

Crucially, Maus I includes one embedded short comic (“Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” appearing in the complete work) about Anja’s suicide, in scratchy expressionist style, which interrupts the animal allegory to show raw grief and implicate the artist himself in the book’s emotional economy; while its most discussed placement is in Complete Maus, the effect remains: Spiegelman makes his own pain exhibit A, refusing to stand above the story.

(Note: the piece is usually referenced within the combined edition; readers should know it is part of the Maus project’s core testimony about family grief.)

4. Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content: Evidence & Reasoning.

Spiegelman grounds Vladek’s reminiscences in concrete chronology (courtship, Sosnowiec, Srodula ghetto, hiding, black markets, transports), corroborates them with survivor commonalities (barter networks, forged papers, informers, camp systems), and he also shows the limits of any single witness by keeping the tape-recorder and disputes in frame; this is exemplary historiographic honesty.

The narrative never asks you to worship the survivor or the artist: Vladek can be heroic in one panel and infuriating in the next, while Art depicts himself as impatient, exploitative, and ashamed about making a “blockbuster” from his parents’ agony, thus pre-empting the common critique that trauma art is parasitic.

And the book’s emotional thesis is articulated in a line that has become emblematic: “To die, it’s easy… but you have to struggle for life,” a survivor ethic that is not triumphalist but stubborn, insisting on effort without promising redemption.

Does it fulfill its purpose / contribute to its field?

Yes: Maus I helped establish the graphic memoir as a serious literary form, taught in schools and universities, recognized by the Pulitzer Board’s Special Citation in 1992, and canonized by TIME among all-time nonfiction; the work’s ban in 2022 paradoxically demonstrated its continuing pedagogical power as sales spiked and public conversation shifted toward the necessity of confronting historical violence honestly.

It also contributes method: by showing the making of testimony, Spiegelman arms readers against distortion, giving future educators a model for how to teach evidence, bias, and memory’s construction alongside the facts of genocide.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

What compelled me.

First, the braid of present-tense bickering and past-tense terror makes the history stick in my nervous system; I didn’t just learn facts—I watched consequences unfold across decades, and it altered how I interpret immigrant thrift, family fights, and sudden anger.

Second, the animal allegory recalibrated my eye: I started seeing how categories (Jew/Gentile, German/Polish/American) get drawn and weaponized, how masks protect and trap, and how a few visual strokes can teach structural analysis better than a paragraph.

Third, the book’s willingness to make me uncomfortable—especially around Anja’s suicide and Vladek’s racism—kept it honest; it refuses the easy comfort of “good survivor = good person,” and insists that survival is morally messy.

Where I struggled.

Sometimes the frame quarreling felt so abrasive I wanted to look away, and yet I realized that was the point: generational pain is inheritable, and avoidance would be a lie.

At moments, the animal metaphors risk essentializing national groups (e.g., Poles as pigs), which educators must contextualize to avoid misreadings, though Spiegelman’s own meta-commentary helps guide interpretation.

6. Reception / Criticism / Influence

Upon publication in 1986, Maus I expanded the perceived reach of comics, with the full project recognized by the Pulitzer Special Citation in 1992—an institutional watershed often cited as a turning point for graphic literature’s mainstream legitimacy.

It remains on TIME’s lists of essential nonfiction/graphic novels, taught widely, and re-surged to bestseller lists in 2022 when a Tennessee school board banned it for “language” and a “naked mouse,” a move that critics—Spiegelman included—called demented and authoritarian; sales spiked, proving Streisand-effect dynamics in cultural memory battles.

Influence threads outward: contemporary graphic memoirs (from Persepolis to Fun Home) cite Spiegelman as precedent in fusing the personal and political, offering readers a way to process historical violence without losing the specificity of one family’s life. (General canon point; TIME and Pulitzer sources indicate the lineage.)

7. Quotations

“No, darling! To die, it’s easy… but you have to struggle for life! Until the last moment we must struggle together! I need you! And you’ll see that together we’ll survive.” (Vladek to Anja, after Richieu’s death)

“This was 1944… we knew everything. And here we were.” (Vladek on arriving at Auschwitz)

“Friends? Your friends? If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week… then you could see what it is, friends!” (Vladek to young Art in the opening)

“I feel so inadequate trying to reconstruct a reality worse than my darkest dreams.” (Art on the ethics of representation)

8. Comparison with similar works

Compared to Night (Elie Wiesel), Maus I externalizes the ethics of telling by keeping the artist in the frame, showing how testimony is made, argued, and edited; Wiesel’s memoir aims for stripped lyrical gravity, while Spiegelman uses visual metaphor to hard-code memory into the eye. (Comparative method, grounded in the formal features described above.)

Compared to Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi), Maus is darker in palette and colder in panel rhythm, but both use a child/young narrator’s closeness to history to make geopolitics legible at human scale; both also demonstrate how the graphic form invites new readers to history who might otherwise avoid “war books.” (General comparison; reception history shows both are canonical.)

9. 7 Reasons This Unforgettable Book Changed Everything.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus (specifically the first volume, Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History) is not merely a book; it is a cultural and literary watershed moment. Published in the 1980s, this work defied categorization, broke down literary barriers, and fundamentally altered how we understand both the Holocaust and the potential of the comic book medium.

Here are seven powerful reasons why this unforgettable book irrevocably changed literature, history, and art:

1. It Elevated the Comic Book to Literary Art with the Pulitzer Prize

Before Maus, the comic book format was widely dismissed as juvenile entertainment. Spiegelman’s win of the 1992 Pulitzer Prize Special Citation for Maus shattered this perception forever. By honoring a work told entirely in sequential art, the Pulitzer acknowledged the form’s ability to handle the gravitas of historical and human tragedy. This single award legitimized the graphic novel as a serious literary medium, paving the way for future masterpieces and validating the entire field of comics study.

2. It Created a Groundbreaking New Language for the Holocaust

How do you represent the “unspeakable,” as the text itself refers to the Holocaust? Spiegelman chose anthropomorphism. By depicting Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs, he approached the terrifying events “through the diminutive,” shocking the reader out of any sense of familiarity (as noted in the book’s synopsis). This visual metaphor serves several complex purposes:

- It literally embodies the Nazi dehumanization of Jews as vermin (mice).

- It creates a necessary distance, allowing the reader to process the horrific reality through an allegorical lens.

- It highlights the absurdity of racial categorization by reducing national identity to a simple mask.

3. It Pioneered the Story of the “Second Generation” and Inherited Trauma

Maus is just as much about the present as it is about the past. The book weaves two powerful stories: Vladek’s harrowing tale of survival in Hitler’s Europe and Artie’s tortured relationship with his father in Rego Park, New York. This dual narrative structure focused the literary world on the concept of post-Holocaust trauma—the guilt, anxiety, and impossible legacy inherited by the children of survivors. It opened the door for countless subsequent literary works exploring intergenerational trauma.

4. It Revolutionized the Memoir Genre by Fusing Fact and Form

Maus is a memoir, a biography, and a historical account, yet it presents itself as a graphic novel. This blend proved that non-fiction could thrive in the comic format. Spiegelman was meticulously dedicated to Vladek’s eyewitness testimony, but the graphic form allowed him to inject meta-commentary, use abstract visual symbolism, and address his own struggle with the creative process of documenting history. It created a subjective, fragmented, and intensely honest form of historical documentation.

5. It Introduced the Complicated, Flawed Survivor (Vladek Spiegelman)

Vladek Spiegelman is a brilliant, resourceful, and deeply flawed protagonist. Spiegelman refused to sanitize his father, presenting him not as a saintly hero but as a complicated, stingy, racist, and sometimes maddening old man—all traits attributed, in part, to his survival mechanism and trauma. This portrayal challenged the conventional, often romanticized narrative of the Holocaust survivor, asserting that survival is messy, moral, and morally compromising.

6. It Forced a Crucial Conversation on Ethics and Representation

The use of anthropomorphism, while groundbreaking, sparked intense ethical debate: Is it appropriate to use “cartoons” to depict the Holocaust? The controversy only amplified the book’s importance. It forced critics and readers alike to analyze the ethics of artistic representation, the nature of memory, and the limits of the comic medium. Maus proved that controversy, when rooted in moral sincerity, is a powerful engine for cultural change.

7. Its Enduring Topicality in the Face of Censorship

The book’s recent history—specifically its banning in certain school districts—further cemented its revolutionary status. When a book about the Holocaust, a historical fact, is challenged, it underscores the fragility of memory and the continuous relevance of its themes. Maus became a global symbol for the fight against censorship and a reminder that its lessons on racism, persecution, and historical memory remain vitally important today.

10. Conclusion

Overall, Maus I: My Father Bleeds History succeeds because it refuses easy consolation: it shows survival, not sainthood; love, not sentimentality; memory, not myth.

Its strengths—formal honesty, emotional precision, and historical lucidity—far outweigh its discomforts, which are integral to its pedagogy and ethical stance.

I recommend it to general readers, students, and educators seeking a rigorous, accessible entry into Holocaust testimony, intergenerational trauma, and the power of graphic narrative to carry the weight of history without breaking under it.

And I recommend pairing it with survivor statistics and contemporary news about remembrance, because Spiegelman’s book is not a museum piece—it’s an alarm clock that keeps going off as witnesses fade and distortion rises.