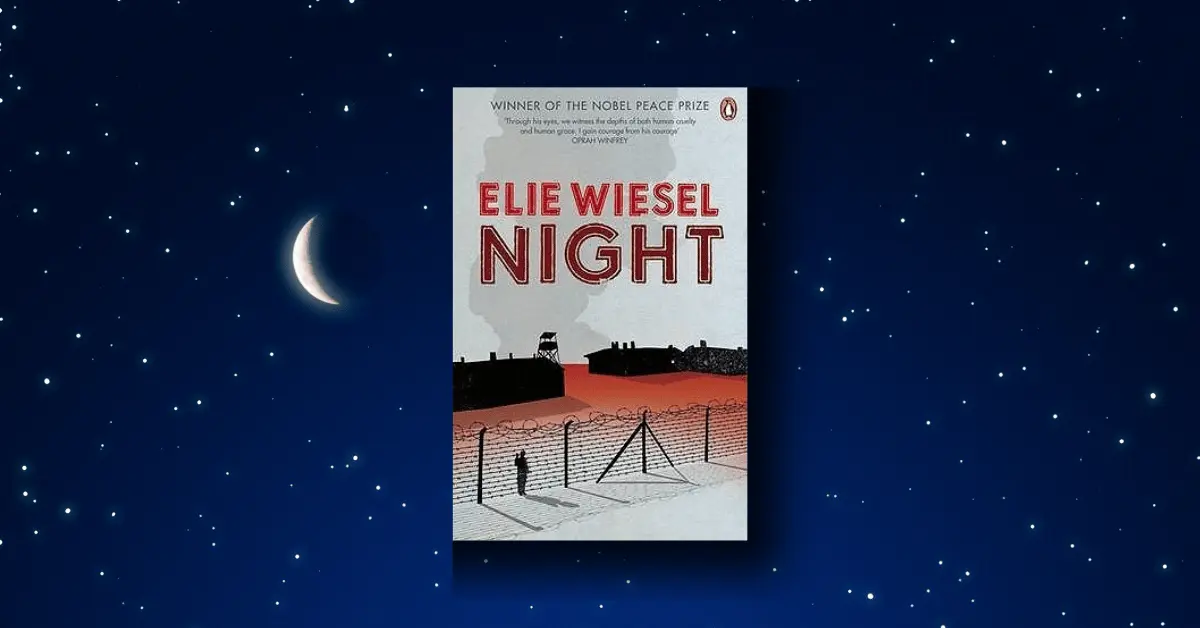

The book is Night, written by Elie Wiesel, a Romanian-born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, and Holocaust survivor. First published in 1956 in Yiddish under the title Un di velt hot geshvign (“And the World Remained Silent”), it was later abridged and translated into French (La Nuit, 1958) and English (Night, 1960) by Wiesel himself, with the help of French writer and Nobel Laureate François Mauriac.

Night is a Holocaust memoir, a piece of autobiographical literature that defies classification—it is a document, a testimony, and a work of literary craft, all in one. The narrative follows Wiesel’s harrowing journey through Auschwitz, Buna, and Buchenwald, where he witnessed inhumanity that tested the limits of human endurance, faith, and sanity.

Elie Wiesel was 15 when he and his family were deported to Auschwitz in 1944. His mother and younger sister were killed upon arrival. Wiesel and his father endured forced labor and starvation until the latter’s death shortly before liberation. The events Wiesel recounts are more than personal; they stand as symbols of collective trauma.

He would go on to become a voice for Holocaust remembrance, warning against silence and indifference. His Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 was awarded for speaking out “against violence, repression and racism.”

Night argues that memory is resistance—a moral obligation. It is a chronicle of spiritual devastation, but also a tribute to the dignity of survival. The core argument is best summarized in Wiesel’s words:

“To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.” (Wiesel, Night)

Table of Contents

Who Was Elie Wiesel?

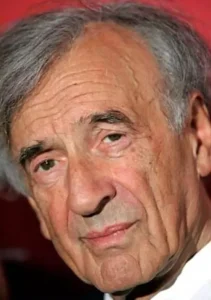

Elie Wiesel was a Holocaust survivor, writer, teacher, and Nobel Laureate who dedicated his life to bearing witness to the horrors of genocide and championing human rights. Best known for his memoir Night, Wiesel became a powerful voice for Holocaust remembrance and moral responsibility.

Early Life in Sighet

Elie Wiesel was born on 30 September 1928 in Sighet, a small town in the Carpathian Mountains of northern Transylvania, which was then part of Romania. He was raised in a deeply religious, Orthodox Jewish household. His father, Chlomo, was a shopkeeper and community leader, while his mother, Sarah, nurtured a home grounded in faith and tradition. The community of Sighet’s Jews ranged from 10,000 to 20,000, and Wiesel spent his youth immersed in religious studies, particularly the Talmud and Kabbalah.

During the early years of World War II (1941–1943), Sighet remained relatively untouched. But everything changed in March 1944 when Nazi Germany invaded Hungary. This began a swift and brutal campaign of Jewish deportation.

Auschwitz and Buchenwald: The Holocaust Years

Wiesel, just 15 years old, was deported along with his family in May 1944. They were forced into cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the Nazi extermination camp in occupied Poland. Upon arrival, Wiesel was separated from his mother and youngest sister, Tzipora, who were murdered in the gas chambers. He remained with his father, Chlomo, as they endured unimaginable suffering in several camps, including Buna (Monowitz) and Buchenwald.

Their experiences were filled with starvation, forced labor, beatings, and the constant threat of death. Wiesel witnessed his father’s gradual physical decline. In January 1945, just before the camp was liberated by the U.S. Army, Chlomo died of dysentery and exhaustion. Elie Wiesel survived, but the trauma marked him for life.

Night: From Silence to Testimony

After the war, Wiesel lived in a French orphanage and began to rebuild his life. In 1954, he completed a powerful Yiddish manuscript titled Un di Velt Hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent), which detailed his Holocaust experience. This was later condensed and translated into French (La Nuit, 1958) and then English as Night in 1960.

Night is not just a memoir—it is a haunting cry from the depths of human suffering. In stark, spare language, Wiesel recounts his transformation from a devout boy to a hollow survivor, wrestling with his loss of faith, identity, and hope.

Moral Witness and Global Voice

Wiesel’s journey from trauma to testimony made him one of the most respected voices on genocide and injustice. Over the decades, he wrote more than 50 books, including Dawn and Day, which, along with Night, form his Holocaust trilogy. His work spans fiction, essays, and theology, all exploring themes of memory, faith, suffering, and resilience.

In 1986, Elie Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee praised him as a “messenger to mankind” who, despite unimaginable suffering, “delivered a message of peace, atonement, and human dignity.”

Educator, Activist, Humanitarian

Wiesel didn’t confine his advocacy to the Jewish experience. He became a prominent human rights activist, speaking out against atrocities in places like Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur, and Cambodia. In 1978, he was appointed chairman of the Presidential Commission on the Holocaust by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, which led to the creation of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

He also taught at Boston University, where he held the title of Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, inspiring generations of students with his ethical vision.

Legacy and Death

Elie Wiesel passed away on July 2, 2016, at the age of 87. His death marked the loss of one of the last living voices of the Holocaust generation, but his words live on.

His legacy is etched not just in literature, but in the moral compass he offered the world: to never be silent in the face of injustice, to remember the past so it may never be repeated, and to honor the dignity of every human life.

In His Own Words

“For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

— Elie Wiesel

Background: A Chronicle Born in Silence

Elie Wiesel did not initially intend to publish Night. For nearly a decade after liberation, he remained silent. Encouraged by François Mauriac, he finally wrote over 800 pages in Yiddish, later condensed into the slim but searing version we read today.

The world in which Night emerged was, ironically, not entirely receptive. In post-war Europe and America, people were eager to “move on.” Holocaust literature was still rare. As Wiesel later recalled:

“The world did know and remained silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever human beings endure suffering and humiliation.”

The book’s title, Night, encapsulates its central metaphor—the descent of humanity into darkness. This night is physical, spiritual, moral, and cosmic. It is the night when a 15-year-old lost his God, his family, and his illusions about mankind.

Summary of Night

Main Events by Chapter Highlights:

Night by Elie Wiesel, first published in 1956 in Yiddish and translated into English in 1960 by Stella Rodway, is more than just a Holocaust memoir—it’s a piercing, personal account of faith, loss, survival, and silence in the face of evil. Elie Wiesel, who later became a Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1986, wrote Night not just to recount events but to ensure memory triumphs over denial.

The memoir spans Eliezer’s journey, the narrator’s younger self, from Sighet (a town in Transylvania) to Auschwitz, Buna, Gleiwitz, and Buchenwald. Through a blend of stark narrative and poetic restraint, Wiesel confronts the horrors of genocide, the collapse of humanity, and the quiet death of God in the barracks of Auschwitz.

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed.” — Night, p. 34

Part I: Life in Sighet and the Foreshadowing of Horror

The memoir opens in Sighet, Romania, in 1941. Eliezer is deeply spiritual, devoted to studying the Talmud and Kabbalah, despite his father’s discouragement of mysticism. His mentor, Moshe the Beadle, guides him. After Moshe is deported and returns with horrifying tales of mass executions in Poland, no one believes him. The denial runs deep.

This false sense of security is haunting. Even when foreign Jews disappear, and German officers arrive, the Jewish population of Sighet remains hopeful. The ghettoization begins quietly—Jews are moved into cramped quarters, forbidden from leaving homes, attending synagogue, or owning valuables.

“The ghetto was ruled by neither German nor Jew; it was ruled by delusion.” — Night, p. 12

Eventually, deportation trains arrive. Crushed into cattle cars, with 80 people per carriage, Jews are given little water and almost no food.

Part II: Arrival at Auschwitz and the First Night

The train arrives at Birkenau, part of the Auschwitz complex. The scene is chaotic—babies thrown into flames, families split by SS officers. Eliezer and his father are separated from his mother and sisters (whom he never sees again). This is where the night of horrors begins.

“Men to the left! Women to the right!” — Night, p. 29

An inmate tells them to lie about their ages to survive—Eliezer says he’s 18, his father 40. Another inmate threatens them to work or perish: “Here, there are no fathers, no brothers, no friends. Everyone lives and dies for himself alone.”

That night, they see babies burned alive, something that breaks Eliezer’s faith:

“Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the small faces of the children…” — Night, p. 34

They are shaved, disinfected, and tattooed. Elie becomes A-7713. That number is now his identity.

Part III: Life in Buna and the Slow Death of Faith

Buna is where daily life becomes mechanical and hopeless. The prisoners work at a warehouse, and beatings are routine. Elie and his father manage to stay together. They witness a child hanged — a “sad-eyed angel”, whose death lasts painfully long.

“Where is God now?” someone behind me asked.

“Where is He? Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows.” — Night, p. 65

Elie begins to lose his belief in a just, merciful God. Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur come and go with silence and starvation. The boy who once fasted with passion now questions:

“Why should I bless His name? What had I to thank Him for?” — Night, p. 67

This part of Night by Elie Wiesel reflects how the Holocaust not only stripped people of life, but also of identity, dignity, and faith.

Part IV: March to Gleiwitz – Snow, Death, and the Loss of Self

In the winter of 1944–45, the camp is evacuated. Thousands are forced to march through the snow for over 40 miles with no food, under extreme conditions. Prisoners fall and are shot. Elie’s foot is infected, yet he limps with his father to Gleiwitz.

This march is among the most harrowing sections of Night by Elie Wiesel:

“We were masters of nature, masters of the world. We had transcended everything—death, fatigue, our natural needs. We were stronger than cold and hunger…” — Night, p. 83

In Gleiwitz, prisoners are piled into a shed. Many are already dead. Elie saves his father repeatedly, while others trample one another for air.

Part V: Final Journey to Buchenwald and Death of the Father

From Gleiwitz, they’re transported in open cattle cars. Only 12 survive out of 100. The scenes are apocalyptic—bodies thrown from cars, men killing each other over crumbs.

“I watched other hangings. I never saw a single victim weep. These withered bodies had long forgotten the bitter taste of tears.” — Night, p. 85

In Buchenwald, Eliezer’s father becomes extremely ill. Elie watches his father wither, beg for water, and suffer beatings from SS officers and fellow inmates. One night, Elie awakes to find his father gone—likely taken to the crematorium.

“I did not weep, and it pained me that I could not weep. But I was out of tears.” — Night, p. 106

Elie survives only for food now. He becomes numb, void of hope, faith, or emotion.

Part VI: Liberation and the Final Reflection

In April 1945, the camp is liberated by American forces. Elie is too weak to move. After liberation, he gazes into a mirror for the first time since the ghetto.

“From the depths of the mirror, a corpse was contemplating me. The look in his eyes, as they stared into mine, has never left me.” — Night, p. 109

The memoir ends with a haunting image—not of celebration or closure, but of trauma etched in a boy’s hollow gaze.

Key Themes in Night by Elie Wiesel:

- Dehumanization: Systematic stripping of identity.

- Loss of Faith: God’s silence haunts the narrative.

- Father-Son Bonds: Their relationship offers one of the few emotional anchors.

- Silence and Memory: The book is Wiesel’s protest against forgetting.

Main Arguments, Themes, and Lessons:

Here are the central lessons Night leaves us with:

- The Fragility of Faith: Elie loses his belief in a just and benevolent God.

- The Death of Innocence: The memoir charts his transformation from a devout boy to a hollow survivor.

- The Silent World: Wiesel blames not only the Nazis, but also the world that stayed quiet.

- The Father-Son Bond: A rare flame of human love that resists total extinction.

- The Ethics of Memory: Remembering becomes a sacred act, a shield against repetition.

This structure is linear and chronological, but it also mirrors a spiritual descent—from community to camps, from identity to anonymity, from belief to silence.

Evaluation of Content

Elie Wiesel never sets out to write a thesis-driven book in Night. Instead, what he offers is a moral witnessing, an existential questioning of whether human life retains any dignity or meaning when placed under extreme conditions. In doing so, he doesn’t argue his point—he lives it on the page.

Through tightly packed vignettes, Wiesel offers a stunning counterargument to any sanitized version of history. The narrative’s power lies in its brevity and emotional force. For instance, in the now-iconic line from a Nazi execution scene, he writes:

“That night, the soup tasted of corpses.” (Ch. 4)

In just eight words, Wiesel does what many writers take pages to do—convey the total collapse of normalcy, appetite, and life.

There is no analytical detachment in Night. Wiesel is both the subject and the lens, and that proximity to pain makes his voice irrefutable. When Wiesel describes watching the hanging of a child:

“For more than half an hour he stayed there, struggling between life and death, dying in slow agony under our eyes.” (Ch. 4)

We are not asked to feel pity. We are forced to stand in that crowd and witness—which is precisely his purpose. As Wiesel would later say in speeches:

“The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.”

“Because I remember, I despair. Because I remember, I have the duty to reject despair.”

So, does Night by Elie Wiesel fulfill its purpose? Unquestionably, yes. Night is one of the most important personal accounts of the Holocaust ever written. It turns memory into a weapon against apathy.

Style and Accessibility: How Wiesel Writes What Can’t Be Spoken

Wiesel’s prose is minimalist, sparse yet loaded with emotional weight. Each sentence cuts like a scalpel. He resists the temptation to romanticize or philosophize excessively. Instead, he chooses raw honesty, even when it implicates him or shows emotional numbness.

Here’s how he describes his reaction after seeing his father struck by a Kapo:

“I had watched and kept silent. Only yesterday, I would have dug my nails into this criminal’s flesh. Had I changed that much?” (Ch. 4)

This question—“Had I changed that much?”—haunts the entire narrative. It encapsulates the theme of moral erosion, how survivors often lose not only their families and faith but also their sense of self.

Night by Elie Wiesel is very accessible in terms of language. Even young readers can follow it, but the emotional toll makes it a profoundly adult text.

Themes and Their Relevance Today

Let’s unpack the central themes and see how they resonate in 2024 and beyond.

1. Loss of Faith

Wiesel was once a devout Jewish boy who studied the Talmud. But in Auschwitz, he confronts a silent God:

“Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.” (Ch. 3)

His spiritual breakdown mirrors a broader existential crisis. In a world riddled with genocide, war, and systemic racism, Wiesel’s questions are still ours.

2. The Human Capacity for Evil

The Nazis’ dehumanization process—shaving heads, assigning numbers, public hangings—is a horrifying lesson in how ordinary people become executioners. As Hannah Arendt would later call it, it’s “the banality of evil.”

3. Survival vs. Humanity

Perhaps the most tragic lesson is how survival sometimes comes at the cost of moral decay. The scene where a son beats his father for a crust of bread shows this bitter truth.

4. Silence and Indifference

Wiesel’s most repeated warning is against silence:

“I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation.”

In today’s climate of refugee crises, political silence on genocides, and social media apathy, Night remains heartbreakingly urgent.

Author’s Authority: Why Elie Wiesel Deserved the World’s Ears

Wiesel’s authority is not academic; it’s lived. But he wasn’t “just a survivor.” After the war, he became one of the leading moral voices of the 20th century. He was awarded:

- The Nobel Peace Prize (1986)

- The Presidential Medal of Freedom

- The Congressional Gold Medal

- Numerous honorary doctorates and literary awards

But more than titles, Wiesel’s moral compass never bent. He used his fame to speak for victims in Darfur, Bosnia, and Rwanda, urging the world to remember:

“To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

Strengths of Night by Elie Wiesel

1. Raw Emotional Authenticity

Perhaps the most powerful strength of Night by Elie Wiesel is that it feels real. There’s no artistic polish to soften the brutality. It’s not a dramatized memoir—it’s a wound, left open for the world to see.

When Elie Wiesel describes his father’s slow death, he doesn’t cry. He doesn’t dramatize. He simply says:

“I did not weep, and it pained me that I could not weep.” (Ch. 8)

That emotional numbness says more about trauma than any tear ever could. His honesty in showing both strength and shame is what makes Night by Elie Wiesel universal.

2. Universal Themes Beyond the Holocaust

While Night is rooted in the Shoah (Holocaust), it transcends it. Night by Elie Wiesel speaks to:

- Any oppressed population

- Any refugee forced to abandon identity

- Anyone who has watched injustice unfold and felt helpless

Its simplicity and universality make it required reading in over 100 countries, and it has been translated into more than 30 languages.

3. Educational Power

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Wiesel’s work, particularly Night, is one of the top 5 most frequently assigned Holocaust memoirs in U.S. high schools. In fact, after Oprah Winfrey chose it for her Book Club in 2006, sales of Night by Elie Wiesel jumped over 500%, reaching new generations of readers.

❌ Weaknesses or Limitations

Even masterpieces aren’t without their critiques, and a fair analysis of Night by Elie Wiesel must include its challenges.

1. Sparse Character Development

Since Night is largely about Elie and his father, Night by Elie Wiesel doesn’t dwell on secondary characters. Some critics argue that this makes the world feel narrow. But Wiesel intentionally avoids distractions—he wants us focused not on individuals, but on the experience.

2. Lack of Historical Framing

Night by Elie Wiesel doesn’t offer background on World War II, Nazism, or the politics of genocide. It’s not meant to be a history textbook. But that absence can confuse readers unfamiliar with the context.

Still, as Elie Wiesel once explained:

“I wanted to show the face of the victim, not the ideology of the killers.”

And that’s what he does—brilliantly.

Reception, Impact & Global Influence

From its first publication in 1956 (as La Nuit in French) to its English translation in 1960, Night by Elie Wiesel has undergone a transformation—from a quiet testimony to a global moral compass.

Literary Reception

- The New York Times called it “a slim volume of terrifying power.”

- The Guardian noted that it “remains one of the most powerful accounts of the Holocaust ever written.”

- The Nobel Peace Prize committee honored Wiesel in 1986, stating:

“Wiesel is a messenger to mankind. His message is one of peace, atonement and dignity.”

Cultural Reach

- Sold over 10 million copies worldwide

- Translated into 30+ languages

- Became part of U.S. common core curriculum

- Sparked documentaries, plays, and tributes globally

In Media

In Oprah’s landmark visit with Elie Wiesel to Auschwitz (aired in 2006), she said:

“You cannot read Night and remain the same.”

Iconic Quotes from Night by Elie Wiesel

Here are some of the most haunting and unforgettable lines, each of which has become a timeless warning:

- “Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp… which turned my life into one long night…” (Ch. 3)

- “Where is God now?” someone asked. And I heard a voice within me answer: “Where is He? Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows…” (Ch. 4)

- “To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

- “Human suffering anywhere concerns men and women everywhere.”

- “There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest.”

These quotations are regularly cited in UN remembrance ceremonies, Holocaust education programs, and academic journals, emphasizing their enduring resonance.

Comparison with Similar Works

| Work | Author | Similarity | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Man’s Search for Meaning | Viktor Frankl | Also Holocaust memoir | More philosophical and psychological |

| Survival in Auschwitz | Primo Levi | First-person Nazi camp experience | More analytical and less emotionally driven |

| The Diary of Anne Frank | Anne Frank | Eyewitness testimony of persecution | Ends before the worst horrors begin |

| Schindler’s List (film) | Steven Spielberg (based on Keneally’s book) | Holocaust visual narrative | Focuses on rescuers, not survivors |

What sets Night apart is the power of silence, the role of spiritual loss, and the father-son bond that holds until the very last breath.

10 Shocking Lessons from Night by Elie Wiese

1. Silence Can Be More Terrifying Than Violence

Wiesel writes, “Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live.” This isn’t just about the absence of sound—it’s about the world’s horrifying silence while millions perished. The lesson is clear: when good people say nothing, evil triumphs. Silence becomes complicit.

2. Dehumanization Happens Gradually—And Completely

From the moment Elie and his family arrive at Auschwitz, the systematic stripping of identity begins. “A truck drew close and unloaded its hold: small children. Babies! Yes, I did see this, with my own eyes… children thrown into the flames.”

The Nazis didn’t just kill bodies—they dismantled souls. The lesson? Injustice often starts small. By the time it’s visible, it might be too late.

3. Faith Is Not Immune to Despair

One of the most harrowing transformations in Night is Elie’s spiritual disintegration. After witnessing the hanging of a child, he writes:

“Where is God now? … Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows.”

This is the moment faith collapses—not just in God, but in meaning. Wiesel teaches us that faith is fragile in the face of overwhelming cruelty—and sometimes, it must be rebuilt from ashes.

4. Hunger Can Erode Humanity

Starvation recurs like a haunting drumbeat. At one point, a father is beaten to death by his own son for a scrap of bread.

“I watched other hangings. I never saw a single victim weep. These withered bodies had long forgotten the bitter taste of tears.”

Wiesel doesn’t blame them. He shows how hunger can override moral instincts. The lesson? Extreme conditions reveal what we’re capable of—not always nobly.

5. Father-Son Bonds Are Sacred—But Vulnerable

Elie’s relationship with his father sustains him throughout. But even that bond is tested by exhaustion.

“If only I didn’t find him! If only I were relieved of this responsibility… I could use all my strength to fight for my own survival…”

This moment shocks with its honesty. Even the deepest love can buckle under unthinkable pressure. But Wiesel still honors it as one of the few lights in the darkness.

6. Memory Is a Form of Resistance

The entire Night by Elie Wiesel is, at its core, an act of remembering. Wiesel tells us:

“To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

The Nazis tried to erase Jews not only from life, but from history. Wiesel’s words fight that erasure. Memory, he insists, is sacred—and revolutionary.

7. The Worst Suffering Is When Hope Dies

When the prisoners are forced to run in the freezing night, Wiesel writes:

“The idea of dying, of ceasing to be, began to fascinate me.”

It’s not pain that defeats him—but hopelessness. The lesson here is brutally honest: physical suffering is endurable. Hopelessness is not.

8. Evil Can Look Ordinary

The SS officers aren’t monsters in appearance. Some smile. Others play music. Wiesel notes:

“They were our first oppressors. They were the first faces of hell and death.”

This subtle observation reminds us: Evil wears human faces. It speaks softly. It often looks like bureaucracy, uniforms, neighbors. That’s what makes it so dangerous.

9. Survival Often Involves Guilt

Survivor’s guilt runs through Night like a deep wound.

“I was afraid of finding myself alone that evening… How good it would be to die here!”

Even surviving Auschwitz doesn’t feel like triumph. Many live haunted by the question: Why me? Wiesel teaches us that surviving trauma doesn’t mean escaping it.

10. We Must “Imagine the Fire” to Prevent the Fire

At the end, Wiesel stares into a mirror and sees “a corpse contemplating me. The look in his eyes as he gazed at me has never left me.”

That look is our responsibility now.

The final, shocking lesson? This isn’t just a Jewish story. It’s a human one. And if we don’t actively remember, actively resist, history is doomed to burn again.

These 10 shocking lessons from Night by Elie Wiesel aren’t just about the Holocaust—they’re about the human condition. About how quickly civilization can unravel, how easily good people can become silent, and how critical it is to remember, to speak, and to feel.

If you’ve never read Night, this is your nudge. And if you have—go back. Not to relive the horror, but to renew the promise: Never Again.

Conclusion: Why Night Still Matters Today

Night by Elie Wiesel is not just a book. It is a scar, a memory, and a mirror. It teaches us that the worst cruelty is not death, but forgetting. In an age where antisemitism is rising again, and where refugee children die nameless in detention camps, Night is no longer just a story of the past—it is a warning to the present.

If you are a human being who still believes in the dignity of others, this book is essential reading.

Recommendation

- For general readers: You will walk away shaken but wiser.

- For students: You’ll gain a firsthand understanding of the Holocaust.

- For scholars or activists: It remains a central ethical and literary touchstone.