What happens when a decent man convinces himself that the No Other Choice title is not a metaphor but a moral alibi?

Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice (2025)—a satirical, black-comic thriller adapted from Donald Westlake’s The Ax—arrives with 139 tight minutes of nerve and nerve-ending comedy, a Venice world premiere on 29 August 2025, an opening-night slot at Busan on 17 September, and a strong commercial lift-off in South Korea from 24 September.

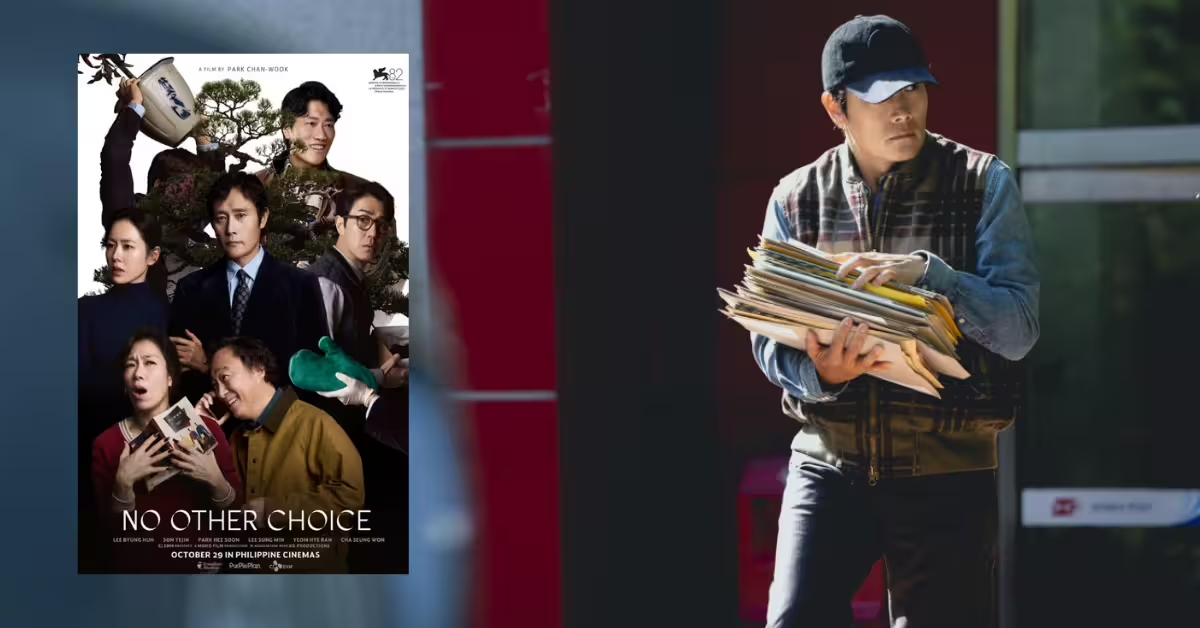

It stars Lee Byung-hun as Yoo Man-su (aka You Man-soo, depending on romanization), Son Ye-jin as his wife Mi-ri, with Park Hee-soon, Lee Sung-min, Yeom Hye-ran, Cha Seung-won and more rounding out a stacked ensemble. The film has been selected as South Korea’s official submission for the 98th Academy Awards’ International Feature category and secured global distribution across key territories.

My first impression, leaving the cinema a little dazed and grinning, is that No Other Choice film feels like Park’s tartest, most lived-in middle-class nightmare: a movie that weeps for dignity even as it laughs at the little tyrants of work, status, and “providing.”

It’s not Park’s best—that bar is planet-high—but it might be his most painfully now.

Background

Park reportedly carried this story for roughly two decades, waiting for a moment when its satire of layoffs and ruthless hiring would sting with full force in an AI-automated economy; 2025 turned out to be that moment.

Venice greeted it as a “state-of-the-nation” shard of glass, and Busan chose it to open their 30th anniversary edition—symbolically crowning a film about work, worth and the cost of “being useful.” Meanwhile distributors moved quickly: NEON took North America; MUBI grabbed the U.K./Ireland and multiple regions; CJ ENM says presales topped 200 countries, breaking a company record.

Then the home audience spoke with their wallets: opening-day admissions crossed ~331,000; within five days it cleared 1 million; by early October, KOBIZ tracked well over 2.3 million admissions, keeping the No Other Choice film firmly in the top slots of the national chart. That’s a remarkable bounce for a caustic satire.

If you’re new to Park Chan-wook, picture an auteur who mixes luscious compositions with moral vertigo. Think Oldboy’s operatic cruelty, The Handmaiden’s clockwork sensuality, and Decision to Leave’s romantic fog—now poured over a layoff thriller that keeps asking: how far would you go to stop falling? (Yes, that question hangs over the No Other Choice film (2025) like a barometer.)

No Other Choice Plot

A man receives an eel for 25 years of loyal service and a termination notice the same week.

That’s Yoo Man-su—paper engineer, father, neighbor, the guy who can fix a feeder jam with his eyes closed—played with exhausted brightness by Lee Byung-hun.

When he’s pushed out of the mill by a cheerful corporate euphemism, he keeps the family serene, promises a new job in three months, and takes whatever temp work will hold the house together. Time slips. The mortgage ticks loud. The No Other Choice film shifts tones—satire to farce to horror—like a seamstress snapping threads.

He becomes a pilgrim of interviews. Each HR foyer is a chapel to youthful productivity; each algorithmic aptitude test another silent insult.

He studies his field like a general studies terrain, and he identifies one fortress that, if taken, would restore his honor: Moon Paper. Inside, a smug foreman treats him as a quaint relic—good at paper, bad at optics—and Man-su walks out with cheeks humming and a notion forming in the back of his skull. The No Other Choice film (2025) doesn’t blare the idea; it lets it congeal.

The idea is murder dressed as meritocracy. He combs trade publications, alumni groups, and rumor to assemble a shortlist of rivals whose résumés mirror his. Then he invents a fake recruitment process—an elegant trap—and social-engineers his targets into private meetings.

The bait is respect; the hook is hope; the line is held by a man who keeps telling himself that he is simply accelerating a decision the market has already made.

Park stages the first “interview” like a corporate training video inverted: the fluorescent glow, the laminated lies, the camera floating just off the moral center.

Bodies and jokes accumulate in a queasy ratio.

What keeps you watching, horrified but complicit, is how tenderly the No Other Choice film keeps faith with Man-su’s home life. Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin) suspends disbelief because she must; she narrates school schedules and dinner prep with the brittle cheer of someone who has memorized a fire drill. The kids sense the air pressure shift but lack the vocabulary. Even the dogs start glancing at doors a beat before bells ring.

The movie understands that economic fear travels like an odor through drywall. Park’s editor, Kim Sang-bum, makes that dread musical, slipping us across days without relief, and the cinematography bathes everything in industrial creams and pale blues, turning kitchens into provisional break rooms.

The murders themselves are masterclasses in tonal whiplash. One rival dies in a scene blocked like a slapstick routine with a fatal prop; another encounter edges into a pathetic confession that detonates the script’s moral charge: Man-su keeps finding mirrors, not monsters. The No Other Choice film (2025) uses these episodes to fracture his self-image. He starts dressing for interviews that don’t exist. He pilfers corporate swag. He rehearses acceptance speeches in car-park reflections.

He makes a spreadsheet titled “Stability Plan” that is just a list of names crossed out. The black comedy never erases sorrow; it frames it.

Moon Paper’s second brush-off pushes him to the brink. He leverages his dead rivals’ expertise in grotesque ways—absorbing jargon like a contagion—and the satire blooms into full, bruised color: taking “competitive edge” literally, Park has his hero eliminate the theoretical “stack ranking” one body at a time.

Here, the film riffs on Westlake’s premise but gestures toward a different endgame, one attuned to 2025’s AI-screened hiring and precarious middle age. Reviewers noted a darker, more ambiguous ending than the novel, and they’re right: Park refuses to hand us catharsis.

In the final stretch, Man-su’s mask slides. A small family ritual—no spoilers on the exact act—collapses into a tableau that feels like a wake for the worker he used to be.

The film’s last movement is a quiet howling: Park steps back from the killings to show the machine that made them thinkable. Lee Byung-hun’s face, so gifted at registering fractions of shame, carries the last five minutes like a fragile bridge between “I had” and “I did.”

You don’t leave thinking “serial killer.” You leave thinking “severance.”

No Other Choice Analysis

1. Direction and Cinematography

Park’s vision here is satirical scalpel, not grand guignol hammer.

The camera glides as if giving HR a tour—wry, composed, and just a little proud of the facility. In crowd scenes, he blocks Man-su at the edge of frames, half-obscured by glass partitions or signage; in home scenes, he shoots from counters and corridors at a child’s height, miniaturizing the adults’ authority. The color palette drifts from entropic beige to cold steel as Man-su slides from embarrassment to decision, with a few delirious, dreamlike inserts that critics rightly latched onto at Venice. The result is a visual language of being “out-processed” by your own life.

The No Other Choice film also indulges Park’s love of transitions: smash-cuts that land like HR memos, match-cuts that tie bodies to machinery, and an occasional slow, ironic dolly into office equipment treated like religious relics. It’s funny until it isn’t. The Guardian called it a “sensational state-of-the-nation satire,” which is accurate; the images do more diagnosing than the dialogue ever could.

Kim Woo-hyung’s cinematography goes for lens choices that slightly over-dignify banal rooms, a trick that reads as empathy: the film keeps offering Man-su beautiful frames he can’t quite deserve anymore.

This is Park staging the tragedy of competence in a world that has automated its appreciation.

2. Acting Performances

Lee Byung-hun is devastating because he never begs you to like him.

He builds Man-su from tiny management habits—aligning pens, pre-filling forms, writing “action items” in the margins of family life—and lets panic seep in through humor. Son Ye-jin matches him beat for beat as Mi-ri, especially in those small domestic scenes that prove how hard it is to confess failure in a home you are trying to keep upright. Their chemistry is the sound of two people pretending today is fine so tomorrow can happen.

Supporting turns from Park Hee-soon, Lee Sung-min, Yeom Hye-ran, and Cha Seung-won give the No Other Choice film (2025) its textured social world: rivals who are not monsters, managers who are not villains—just participants in the same faith system. That’s the horror and the joke. The Daily Beast’s “funniest satire” tag makes sense here: performances modulate to let cruelty play as etiquette.

I kept flashing back to Lee’s on-stage moment at TIFF’s Tribute Awards—first South Korean actor so honored—which now reads like a sly preface to this performance’s control. He turns middle-aged employability into a thriller. (tiff.net)

3. Script and Dialogue

The screenplay (Park Chan-wook with collaborators including Lee Kyoung-mi) takes Westlake’s premise and translates it into the 2025 cadence of layoffs, dashboards, and “culture fit.”

Dialogue is office-grade unsentimental; even the jokes feel like things people would mutter in break rooms. The pacing is Park’s usual high-wire act: long setup, brutal middle, elegiac finale. If there’s a weakness, it’s that a couple of mid-film “interviews” echo each other beat-wise—but the repetition reads as a structural bit (competitors blend when a machine ranks them). As a viewing experience, I found the repetition productive: it turns murder into a work routine, which is the point.

A small masterstroke: the No Other Choice film keeps giving Man-su lines that are perfectly reasonable one micrometer to the left of where he’s standing.

That’s how it sells his self-deception.

4. Music and Sound Design

Jo Yeong-wook’s score slides between sly metronome and melancholy hymn.

You hear little pulses under fluorescent scenes—office music by other means—and then warm, almost home-movie cues around the children that feel, in context, like memories refusing eviction. The sound design turns printers, laminators, and press rollers into percussion; when violence punctures the soundscape, the effect is comic until the ring of a dropped tool empties the room. (Technical credits and music team listings corroborate the film’s polished sound pipeline).

The No Other Choice film (2025) keeps the mix clean, a choice that amplifies dread: the quiet after the gag is where your stomach drops.

Silence, here, is headcount.

5. No Other Choice Themes and Messages

This is a film about usefulness as identity—and what happens when usefulness is repossessed.

Layoffs recode virtue as redundancy; HR recodes character as “fit”; ATS algorithms turn a life into a few green ticks. Park layers in satire of masculinity too: Man-su’s “provider” script becomes his self-harm. The family doesn’t need a hero; they need honesty, but our hero is fluent only in competence. The No Other Choice film thus dramatizes a very contemporary sin: outsourcing ethics to the market and then claiming the market made you do it.

Is it social realism? Not exactly. It’s fable-realism—exaggeration with receipts. Reuters reports Park explicitly tying the project’s urgency to the AI era; that’s the film’s timeline and its thesis. The ending (no spoilers) offers an image that feels like a eulogy for agency under mechanization.

In other words: “no other choice” is a spell, and spells work because people agree to be enchanted.

Breaking it hurts.

Comparison

Think Costa-Gavras’ The Axe (2005) but angrier at systems, gentler with people.

Where The Axe stayed closer to satirical procedural, Park’s No Other Choice film (2025) absorbs the past decade’s churn—platform capitalism, quantized CVs, domestic precarity—and lets it leak into every frame.

Compared with Park’s own Decision to Leave, this is less baroque romance, more broken-hearted sociology; compared with Oldboy, it swaps operatic revenge for office-grade rationalization. The result is uniquely 2025: both funnier and sadder about how ordinary cruelty becomes policy.

If you loved Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite or Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, the No Other Choice film sits in that neighborhood, though its comedy is blacker, its camera more fetishistic about process.

Park is diagnosing class anxiety with a smile sharp enough to cut a feed roller.

No Other Choice Audience Appeal

Who is this for? Anyone who’s filled out an online application and felt smaller afterward.

Cinephiles will savor the craft; casual viewers will recognize the jokes and the dread. Early critical response at Venice was widely positive, with UK press particularly taken by the film’s tonal balancing act; at home, admissions data show strong word-of-mouth legs during the Chuseok window. The selection as South Korea’s official Oscars submission gives it a clean awards-season runway; TIFF’s Tribute spotlight on Lee Byung-hun adds international heat.

On the distribution front, NEON is lining up a stateside push (trailer drops have begun), and MUBI is primed for a tasteful arthouse roll-out across multiple territories—signals that the No Other Choice film (2025) will enjoy both prestige and platform support.

Quick stat check for the box-office-minded: ~331k opening day; ~1.07M in five days; ~2.34M+ admissions by early October; 139-minute runtime. These figures help you triangulate both the film’s scope and its stamina.

If your taste tilts to acidic workplace comedies with philosophical aftertaste, this is a must-see.

6. Personal Insight

I watched No Other Choice film in a week when a friend’s mid-career layoff surprised exactly no one—not because he was underperforming, but because the company’s “strategic realignment” required a certain number on a slide.

We grab our worth from whatever’s closest: a KPI, an inbox, a title that makes our parents nod at weddings. When that scaffolding jerks away, many of us do what Man-su does in act one—not kill people, but build a beautiful “later” to stop a present from collapsing.

The No Other Choice film (2025) makes that self-talk visible. It’s unkind to the story we tell about “being a good provider”: how it smuggles in hierarchy, silence, and a willingness to externalize pain as policy.

I didn’t see a “villain origin story”; I saw a social script that turns normal aftershocks—shame, fear, pride—into violence when a person can’t admit loss out loud. That is a contemporary problem dressed in thriller clothes.

The film also updates the “job killer” narrative for the algorithmic age. There’s a difference between a boss firing you and a dashboard de-prioritizing you. The second is cleaner; it’s hard to hate a bar chart. Park’s satire understands that in 2025, violence often wears the smile of frictionless process.

Man-su’s fake hiring funnel is a grotesque parody of the real thing: ghost postings, ATS black holes, interview loops with no center. Watching him mimic the machine felt like watching a body reject a transplant—the immune system goes to war with the self. The laugh lines hurt because we recognize the inputs.

What, then, is the counter-story? For me, it was Son Ye-jin’s Mi-ri. In a handful of scenes, she models a different grammar of love: tell me what is true, and we will budget reality together. It’s cinema’s old wisdom—honesty before heroism—rehearsed in a kitchen. I wish the culture of work taught that lesson as explicitly as the No Other Choice film does. We ritualize career victories so loudly that confession feels like failure.

Park’s ending (again no spoilers) refuses a neat redemptive loop; instead it gives us the image of a man who ran out of language for loss.

A practical takeaway? If you’re in a season of precarity, postpone the performance of competence. Schedule embarrassment with a friend. Build a vocabulary of okay to be ordinary in your home, so your job can be a job, not a judge. I left the movie thinking less about villains and more about safety instructions for dignity. That’s a strangely hopeful place to land after 139 minutes of satirical despair. The No Other Choice film (2025) won’t fix the market, but it might fix the mirror: it asks you to replace “no other choice” with “say the hard thing sooner.”

And if you’re curating a film-and-reading lineup around this theme, pair Park’s film with Bong’s Parasite and Han Kang’s The Vegetarian—and then read my deep dive on Apocalypto to see how survival stories mutate across cultures and centuries. (Related internal reads: The Vegetarian, Apocalypto.)

Pros and Cons

Pros

- Stunning visuals and sly, precision-engineered blocking.

- Gripping performances, especially Lee Byung-hun and Son Ye-jin.

- A tonal tightrope—funny until it hurts; then it still makes you laugh.

- Sound design that turns office machinery into percussion.

- Timely themes: layoffs, ATS anxiety, performative masculinity.

Cons

- Slow pacing in parts as mid-film “interviews” echo (deliberate, but you feel it).

- Some viewers may want a cleaner catharsis than Park will allow.

Conclusion

I think the No Other Choice film (2025) is Park Chan-wook working at full diagnostic power: less operatic than Oldboy, less romantic than Decision to Leave, but perhaps more socially surgical than either.

It’s a must-watch for thriller enthusiasts and anyone who has ever refreshed a jobs portal at 2 a.m.—a satire that understands why “no other choice” is a lie that feels like a lullaby.

Rating

4.5/5 stars.