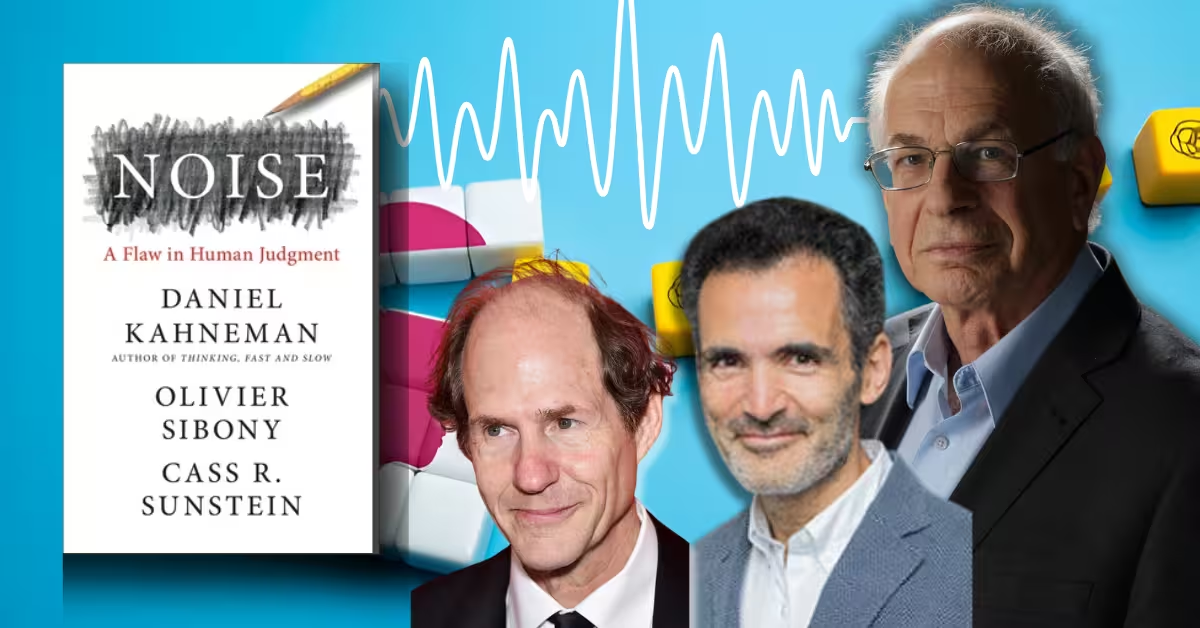

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment is a 2021 nonfiction masterpiece co-authored by the legendary psychologist and Nobel Prize laureate Daniel Kahneman, the management expert Olivier Sibony, and the legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein. The book was published by Little, Brown Spark, an imprint of Hachette Book Group.

Belonging to the genre of behavioral science and cognitive psychology, Noise takes a bold step beyond the domain of biases that Kahneman famously explored in Thinking, Fast and Slow. It dives into the underappreciated yet pervasive flaw in human judgment: “noise.” While biases represent systematic deviations in thinking, noise is about the unwanted variability that clouds decisions—even among experts. The book’s three authors bring a powerful synergy of psychology, management science, and law, giving them the unique vantage point to tackle this multifaceted problem.

The central theme of Noise is that while bias in human judgment has long captured our attention, we have severely underestimated the damage caused by noise—random scatter in judgments that leads to gross injustices, health risks, and financial losses. Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein define noise as “undesirable variability in judgments of the same problem,” and they argue that “wherever there is judgment, there is noise, and more of it than you think”.

This concept is no mere theoretical fancy. In a striking example from their research, the authors describe how underwriters at an insurance company produced median premium estimates for the same fictitious customers that varied by a staggering 55%—five times more than what the company’s executives expected. This shocking revelation underpins the authors’ call to action: to make our institutions and organizations less noisy by adopting what they call “decision hygiene” and noise audits.

100 Best Psychology Books of All Time You Should Try Before Death

By unpacking both the psychological roots and the statistical properties of noise, this book aspires to empower decision-makers—whether in law, business, medicine, or everyday life—to become more consistent, fair, and effective. It aims to open our eyes to a hidden but powerful force that shapes our world and challenges our understanding of what it means to make sound judgments.

Table of Contents

Background

Understanding the significance of Noise requires us to appreciate its intellectual lineage and the fertile ground from which it emerged. Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist, first made his name by challenging the rational agent model in economics with the seminal work Thinking, Fast and Slow, where he famously introduced the world to systematic cognitive biases.

Olivier Sibony, a management consultant and professor, built on this foundation by exploring strategic decision-making under uncertainty. Cass R. Sunstein, a leading legal scholar and co-author of Nudge (with Richard Thaler), has spent decades analyzing how laws and regulations can be structured to improve societal outcomes by gently steering human behavior.

Together, these authors bring a diverse yet complementary set of perspectives to the problem of noise. The book is grounded in both rigorous academic research and compelling real-world examples, revealing how even highly trained professionals—from judges to doctors to underwriters—can make wildly inconsistent decisions when faced with identical information.

The term “noise” itself is not new to statistics or measurement theory. In fact, Kahneman and his colleagues had already explored the concept in earlier research on decision-making variability. But the authors argue that the human mind is particularly ill-suited to recognize randomness; instead, we are pattern seekers, prone to inventing explanations for discrepancies that may, in fact, be nothing more than noise.

One of the most memorable illustrations in the book involves a shooting range analogy: imagine multiple shooters aiming at a target. Some shooters consistently miss the bullseye in the same direction (that’s bias), while others scatter shots all over the target (that’s noise). The latter problem, often overshadowed by discussions of bias, results in a systematic waste of resources and a betrayal of fairness in real-world judgments.

Crucially, the book underscores that noise is not merely a theoretical annoyance. It is a pervasive issue in modern institutions, leading to inconsistent judicial sentences, medical misdiagnoses, and erratic hiring decisions—problems that are not just academic but have profound implications for justice, health, and efficiency.

By identifying noise as an urgent challenge for society, Noise invites us to rethink our confidence in experts and calls for systematic approaches—like noise audits and decision hygiene—to reduce this hidden but costly flaw.

Summary

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment is meticulously structured into six parts, each building on the last to unravel the problem of noise in human decision-making.

Part I: Finding Noise

In the opening section of Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein introduce the concept of noise—a type of error that, unlike bias, is characterized by inconsistency rather than systematic deviation. They vividly illustrate how noise infiltrates judgment through real-world examples like criminal sentencing and insurance decisions, revealing a deeply unsettling insight: even professionals who aim for fairness and accuracy often produce wildly varying judgments under similar circumstances.

One powerful example sets the stage: a study of criminal sentences showed that “the same crime often results in different punishments, depending on which judge hears the case”. This stark inconsistency challenges our assumption that legal systems—or any human judgment system—function predictably. The authors emphasize that variability itself, not just consistent errors (bias), undermines fairness and efficiency.

The authors introduce a compelling analogy: imagine a shooting range where participants aim at a target. “Team B is biased because its shots are systematically off target… Team C is noisy because its shots are widely scattered”. This illustration clarifies how noise differs fundamentally from bias, yet can be equally destructive.

Kahneman and colleagues highlight the invisibility of noise compared to the highly visible bias. They write, “The invisibility of noise is a direct consequence of causal thinking. Noise is inherently statistical: it becomes visible only when we think statistically about an ensemble of similar judgments”. This highlights a central problem: while bias invites causal explanations, noise remains hidden unless systematically analyzed.

Furthermore, the authors introduce the concept of a “noise audit”—a method to systematically measure judgment variability. For example, if multiple insurance underwriters assess the same case but reach different premiums, the scatter in their results reveals the presence of noise. The authors suggest that organizations need to adopt such audits to identify and, eventually, reduce judgment noise.

A particularly thought-provoking passage reads, “The result is a marked imbalance in how we view bias and noise as sources of error”. Here, Kahneman et al. challenge our cognitive habits, emphasizing that while we’re naturally drawn to narrative explanations for errors, statistical noise often evades detection—even though its consequences can be equally harmful.

The authors’ tone is one of gentle yet firm guidance: they push us to confront an uncomfortable reality—that noise is pervasive, hidden, and consequential. They encourage readers to think statistically, adopting what they term the “outside view,” which looks at variability across many judgments rather than focusing narrowly on individual cases.

By the end of Part I, the authors have established a clear thesis: noise is not only ubiquitous but also dangerously overlooked. They argue that reducing noise is essential for improving the fairness and effectiveness of judgments across a wide range of domains, from the courtroom to the boardroom.

Part II: Your Mind Is a Measuring Instrument

In this deeply thought-provoking section, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein deftly unravel how the human mind functions analogously to a measurement device, albeit one riddled with imperfections. They introduce the crucial idea that judgments—whether about guilt, risk, or potential success—are, at their core, acts of measurement. “Judgment can therefore be described as measurement in which the instrument is a human mind,” they assert, highlighting the essential yet error-prone role humans play in assigning values to phenomena.

This part underscores that the aim of judgment is accuracy—akin to getting as close as possible to the bull’s-eye on a target.

However, unlike a finely calibrated machine, human minds are susceptible to both bias (systematic error) and noise (random error). The authors distinguish between the two with precision: “Bias is a systematic deviation; noise is variability”. This distinction is crucial because noise, despite being harder to detect, is often just as damaging.

To make this point tangible, they invite the reader to a simple exercise: using a stopwatch to time five consecutive intervals of exactly ten seconds each, without looking. The result, predictably, is variation—some intervals are longer, some shorter—a concrete demonstration of noise inherent in human cognition. “The variability you could not control is an instance of noise,” they conclude, illustrating how even the most mundane tasks are permeated by variability.

The authors then delve into the more technical dimensions of judgment error. They propose a conceptual framework to analyze noise using statistics. “Noise in their judgments implies error,” they write, drawing a direct line between variability in human judgments and mistakes in decision-making. This insight is especially crucial in fields like medicine, law, and finance, where decisions have profound consequences.

Crucially, the authors introduce the concept of “occasion noise”—the variability in a person’s judgment of the same case depending on irrelevant factors like mood or time of day. They explain that “occasion noise” is often invisible because it’s embedded in the very structure of human cognition. Yet it can have devastating effects. For instance, a doctor might diagnose the same patient differently on different days, introducing dangerous inconsistency into medical care.

The authors also reveal that groups, rather than reducing noise through collective wisdom, can actually amplify it. “Groups often amplify noise in judgments,” they lament, drawing on empirical evidence that group dynamics can introduce further variability rather than consistency. This is a powerful indictment of the common belief that collaboration always leads to better decisions.

Throughout this section, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein emphasize that understanding noise is not just an academic exercise—it’s a moral imperative. They argue that, “Like a measuring instrument, the human mind is never perfect. We need to understand and measure its errors”. This call to action encourages readers to adopt a more scientific, empirical approach to their own judgments, fostering humility in the face of inevitable human fallibility.

In sum, Part II establishes that the mind, while remarkable, is an imprecise measuring device that introduces both systematic and random errors into judgment.

By unpacking the interplay of noise, bias, and occasion noise, the authors lay the groundwork for the subsequent sections, where they will explore how to mitigate these flaws. This part serves as both a warning and a guide: the path to better decisions begins with recognizing that the human mind is as prone to error as any faulty instrument—and that rigorous analysis, rather than intuition, is essential for improvement.

Part III: Noise in Predictive Judgments

In Part III, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein shift their analytical lens to the domain of predictive judgments—a realm where human error can have profound real-world consequences. Here, the authors reveal how noise infiltrates the process of forecasting, affecting everything from financial projections to clinical diagnoses.

They begin by highlighting the inherent challenges of prediction: “A judgment is predictive when it aims to anticipate an unknown outcome,” they explain.

Whether it’s a judge predicting the likelihood of recidivism, a doctor forecasting a patient’s prognosis, or a banker estimating a loan default rate, the human mind is constantly tasked with guessing the future. Yet, as the authors stress, the future is inherently uncertain—and noise only compounds this uncertainty.

A pivotal insight in this section is the authors’ distinction between judgment-based forecasts and algorithmic predictions. Drawing on decades of research, they demonstrate that simple algorithms consistently outperform human experts in predictive tasks. “Rules outperform human judges not because they are smarter but because they are noiseless,” they write, challenging the hubristic belief in human intuition. This insight is both humbling and transformative: it suggests that even the most seasoned professionals are vulnerable to noise, which simple algorithms can sidestep.

The authors illustrate this point with a powerful case study: insurance underwriting. They recount a noise audit in which underwriters assessed identical cases, producing wildly different premium quotes—a classic example of predictive judgment gone awry. This variation is not only inefficient but also costly, leading to financial losses and customer dissatisfaction. The authors assert, “Noise in predictions leads to errors that are systematically costly”.

Another compelling example emerges from medicine. Predictive judgments about patient outcomes—such as survival rates or disease progression—are notoriously noisy. Kahneman and his co-authors highlight how algorithms, trained on large datasets, outperform even the most experienced doctors. “The advantage of rules is that they are noise-free,” they argue, driving home the point that consistency often trumps even the most expert intuition.

A particularly thought-provoking concept introduced here is “objective ignorance”—the idea that even the best prediction models are ultimately limited by the inherent unpredictability of the future. “Objective ignorance puts a ceiling on the accuracy of predictions,” the authors caution. In other words, no matter how sophisticated our models become, there is a fundamental limit to how precisely we can forecast events. This insight compels humility: we must acknowledge that some degree of error—and thus noise—will always persist.

The authors also explore why humans persist in noisy predictions despite evidence favoring algorithms. They identify psychological factors such as overconfidence, the illusion of validity, and a preference for narratives that create a false sense of certainty. “Human forecasters often believe they can see what others miss,” they observe, underscoring how this cognitive bias leads us to favor intuition over statistical reasoning.

This section concludes by challenging readers to confront a sobering truth: wherever there is prediction, there is noise—and it often goes unnoticed. “If you have not noticed noise, it is not because it is absent,” they warn. Rather, it is because the human mind struggles to detect random variability in its own judgments.

In summary, Part III is a clarion call for embracing statistical tools and algorithms as essential allies in reducing noise in predictive judgments. By unpacking the human mind’s inherent limitations, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein urge professionals to relinquish their illusions of infallibility and adopt more systematic approaches to forecasting. The message is clear: acknowledging noise is the first step toward building more reliable—and ultimately fairer—systems of judgment.

Part IV: How Noise Happens

In Part IV, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein dive deep into the psychological and organizational mechanisms that generate noise in human judgment. They peel back the layers of the mind to expose how, even in well-meaning professionals, noise arises from a multitude of hidden sources.

At the outset, they remind us that noise emerges not from malicious intent but from the subtle interplay of factors—individual differences, context, and random chance—that shape every judgment we make. As they put it, “Noise often occurs because different people give different weights to different considerations, even when the situation is the same”. This highlights that variability in weighting factors is a key driver of judgmental inconsistency.

One of the central concepts introduced in this section is heuristics—the mental shortcuts that simplify complex decisions. While heuristics help us navigate a world of uncertainty, they also introduce noise. The authors emphasize that “heuristics can vary from one individual to another”. This variability in shortcuts is not a systematic bias but rather an unpredictable source of scatter in judgments.

They also analyze scales—the mental frameworks we use to rate or rank things, from job candidates to risk levels. Even when two professionals use the same rating scale, they often interpret it differently. For instance, one judge’s “7 out of 10” might consistently differ from another’s, even in identical cases. This misalignment is a major contributor to noise, as highlighted in the line: “Different people use the same scale in different ways”.

Pattern noise—another potent source of variability—arises when different judges emphasize different factors in the same decision. For example, in a hiring decision, one manager might prioritize experience, while another focuses on cultural fit. This divergence in emphasis means that even consistent application of personal standards can produce substantial noise at the organizational level.

A fascinating psychological dynamic the authors explore is the illusion of validity—our tendency to believe that our judgments are accurate simply because they feel right. This illusion blinds us to the presence of noise in our own decisions. As they note, “People are usually oblivious to the degree to which noise contaminates their judgments”. This insight underscores the challenge of detecting noise: because it feels random and invisible, it is easily overlooked.

Moreover, the authors explore how group dynamics can amplify noise rather than reduce it. While groups are often thought to bring wisdom through diverse perspectives, they can also bring variability in emphasis, disagreement about facts, and inconsistent weighting of factors. “Groups often amplify noise,” they caution, challenging the conventional wisdom that collective decision-making is always superior.

The authors also address occasion noise, which is the variability in an individual’s judgments due to transient factors like mood, hunger, or even the weather. For instance, studies show that judges are more lenient after lunch than before. This reinforces the disturbing conclusion that human judgment is subject to factors that should, in principle, have no influence on decisions.

In the concluding chapters of this part, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein highlight that noise is not an anomaly—it is an expected feature of human judgment systems. They stress that organizations need to recognize noise as a systematic problem, not just as a collection of isolated errors. “Noise is part of the human condition,” they assert, and the challenge is to manage it rather than pretend it doesn’t exist.

By the end of Part IV, readers are left with a sobering realization: noise is woven into the fabric of human judgment, arising from our mental shortcuts, inconsistent scales, subjective emphasis, group dynamics, and even our fluctuating moods. To fight noise effectively, one must first understand its many faces—a task that demands humility, self-awareness, and, ultimately, a commitment to rigorous analysis and systematic intervention.

Part V: Improving Judgments

In Part V, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein turn their analytical lens to the crucial question: how can we reduce noise and improve the quality of human judgment? Having shown that noise is pervasive and often invisible, they now offer a suite of pragmatic solutions designed to make decisions more consistent, accurate, and fair.

The authors introduce the concept of decision hygiene, a systematic approach to reducing both noise and bias. They compare decision hygiene to physical hygiene: just as washing your hands reduces the spread of infection, applying decision hygiene techniques can significantly lower judgment errors. They write, “Decision hygiene is a set of procedures that aims to reduce noise in judgment, in much the same way that physical hygiene reduces infections”.

One key technique they highlight is structuring judgments. This involves breaking complex decisions into smaller, more manageable components and assessing them separately before integrating them into an overall judgment. For example, in hiring decisions, instead of asking interviewers to give a single holistic rating of a candidate, they can separately evaluate specific traits like communication skills, technical knowledge, and leadership potential. “Breaking down judgments into separate components improves consistency,” they emphasize.

Another powerful tool is aggregating multiple judgments—a method that taps into the wisdom of crowds. By combining independent assessments from multiple judges (or even from the same judge at different times), organizations can smooth out random variability and produce a more reliable decision. The authors assert, “Aggregating multiple independent judgments is a proven method of reducing noise”.

The authors also explore guidelines and algorithms as noise-reducing strategies. They acknowledge that guidelines are sometimes criticized for being too rigid or mechanical, but they counter that structured decision aids often outperform human intuition precisely because they are consistent and immune to irrelevant fluctuations. They reference studies showing that algorithmic predictions consistently outperform human experts in fields like medicine, finance, and law. “Guidelines reduce noise by making judgments more consistent,” they declare, urging professionals to embrace structure even if it means sacrificing some flexibility.

Debiasing—the effort to counteract known biases—is also a part of decision hygiene. However, the authors caution that debiasing efforts alone are often insufficient. They note, “Debiasing efforts often fail because they target bias without addressing noise”. They argue that noise-reduction strategies should complement, not replace, debiasing efforts.

In a series of fascinating case studies, the authors demonstrate how noise-reduction methods have improved decisions in diverse domains. For example, in medicine, structured diagnostic protocols have reduced variability in doctors’ judgments, leading to more accurate diagnoses. In hiring, structured interviews and scoring rubrics have minimized the influence of irrelevant factors and improved the reliability of candidate assessments. In forensic science, standardized procedures have helped reduce inconsistencies in expert testimony and case evaluations.

One particularly compelling example is the Mediating Assessments Protocol (MAP)—a systematic method the authors designed to structure complex decisions. MAP involves defining the key attributes of the decision in advance, scoring each attribute independently, and then combining the scores to reach a final judgment. They emphasize that MAP helps decision-makers avoid the pitfalls of intuition and overconfidence, leading to more reliable and fair outcomes. “MAP exemplifies the principles of decision hygiene,” they conclude.

Part V is not just a technical manual but a passionate plea for organizations to take noise seriously. The authors urge leaders to conduct noise audits—systematic assessments of judgment variability within their organizations. By measuring noise, organizations can diagnose the scope of the problem and target interventions effectively.

Ultimately, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein convey a sense of optimism. They acknowledge that noise cannot be eliminated entirely but argue persuasively that systematic efforts—like structuring judgments, aggregating opinions, and applying guidelines—can substantially reduce noise and improve the fairness and effectiveness of human judgment. The message is clear: with the right tools and commitment, we can build systems that are not only more consistent but also more just.

Part VI: Optimal Noise

In the concluding section of Noise, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein tackle an intriguing question: is it always desirable to eliminate noise completely? The authors argue that while noise reduction is vital, there are practical, ethical, and psychological reasons why some level of noise might be optimal. “The right level of noise is rarely zero,” they remind us, urging readers to balance the ideal of consistency with the realities of human judgment.

The authors first examine the costs of noise reduction. Implementing strict guidelines, algorithms, or standardized protocols requires time, effort, and resources. In some contexts, these costs may outweigh the benefits. For example, a highly structured process might slow down decision-making or alienate skilled professionals who value their discretion. As they put it, “Reducing noise is not free. Efforts to reduce noise involve investments of time and resources”.

Moreover, they explore the potential trade-offs between noise reduction and human dignity. A system that rigidly standardizes every judgment might feel dehumanizing, reducing people to mere cogs in a machine. This concern is particularly acute in contexts like criminal sentencing or medical care, where individuals rightly expect to be treated as unique cases. The authors caution that “a zero-noise system might be seen as cold and mechanical”. This highlights a tension between fairness through consistency and fairness through individualized consideration.

Another nuanced issue is the rules vs. standards debate. Rules are clear, consistent, and reduce noise, but they can be inflexible and insensitive to context. Standards, by contrast, allow decision-makers to exercise judgment and adapt to specific situations, but they invite noise because different people apply standards differently. The authors note that “Rules reduce noise but at the cost of flexibility; standards preserve flexibility but invite noise”. The challenge, then, is to strike a balance that respects both the need for consistency and the need for human judgment.

They also acknowledge that even efforts to eliminate noise can generate resistance. Professionals often value their autonomy, and guidelines or algorithms may be perceived as threats to their expertise. “Some people may feel that reducing noise undermines their professional identity,” the authors write, recognizing that psychological ownership of one’s decisions is a powerful motivator.

Despite these complexities, Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein remain steadfast in their core message: noise reduction should be a priority for any organization that cares about fairness and accuracy. They urge organizations to conduct noise audits, assess the magnitude of noise in their systems, and experiment with noise-reduction interventions. Yet they also counsel wisdom and pragmatism, reminding readers that “some residual noise may be acceptable or even desirable”.

In the end, the authors emphasize that the goal is not to eliminate human judgment but to improve it. “Noise is not destiny,” they declare. Instead, by understanding the sources of noise, organizations can design better systems, promote fairer decisions, and reduce costly errors—while still respecting the human element that makes judgment meaningful.

Part VI closes with a note of humility and hope: acknowledging that perfect consistency is an illusion, but that even small reductions in noise can yield significant benefits. The authors leave readers with a profound insight: “Noise is a part of human judgment, but it need not be a flaw we simply accept. We can work to contain it, and in doing so, create a more just and effective world”.

Throughout the book, the authors weave in memorable examples:

- The random variability in judges’ decisions, with one judge sentencing a bank robber to five years and another to 18 years.

- Radiologists’ diagnoses of breast cancer that vary between zero and 50% for false negatives.

- Admissions officers favoring different applicant qualities depending on the weather.

The book’s structure is both thematic and argumentative, moving from introducing noise to analyzing its psychological sources, and finally to offering solutions—a masterful design that guides readers from awareness to action.

Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Noise is a tour de force of interdisciplinary thinking, weaving together psychology, management science, law, and behavioral economics into a cohesive argument. Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein convincingly demonstrate that noise—unwanted variability in human judgment—is not just an academic curiosity but a pervasive and costly problem across virtually every domain where humans make decisions.

The authors support their thesis with rigorous empirical evidence, including the striking example from an insurance company where underwriters’ estimates for the same client varied by an average of 55%—a finding that left the company’s executives stunned. They also reference well-documented studies of judges giving wildly different sentences for identical cases, even after controlling for relevant factors. This consistency of evidence across disciplines underscores the robustness of their argument: noise is everywhere, and it’s more serious than most people realize.

The book’s strongest contribution is its call for “decision hygiene,” a compelling suite of techniques designed to reduce noise, including structured judgment protocols, guidelines, and even algorithmic support. The authors argue persuasively that noise audits should be standard practice in any organization that values consistency and fairness.

Style and Accessibility

The prose is characteristically lucid, especially considering the technical nature of the subject. Kahneman’s gift for clear explanation shines, even when discussing abstract concepts like occasion noise or stable pattern noise. Anecdotes—like the variability in radiologists’ breast cancer diagnoses—make the content relatable without sacrificing intellectual depth.

Yet the book occasionally succumbs to repetitiveness; some examples feel overused, particularly the insurance case study, which is referenced multiple times throughout the book. Still, the authors’ skillful use of real-world stories and analogies, such as the shooting range metaphor to distinguish noise from bias, makes even dense sections accessible to a wide audience.

Themes and Relevance

The central theme—wherever there is judgment, there is noise—resonates profoundly in today’s world, where decisions made by humans can carry life-altering consequences. The book is especially timely given increasing debates about algorithmic decision-making. Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein deftly balance the benefits of reducing noise with the caution that too much rigidity can stifle human dignity and flexibility—a nuanced take that strengthens the book’s credibility.

Noise is particularly dangerous because it is invisible. We are often blind to it unless we actively measure it. For instance, in judicial sentencing, similar defendants committing similar crimes may receive vastly different sentences based purely on the random assignment of judges. That inconsistency is noise. Similarly, in fields such as medicine, insurance, hiring, or even simple forecasting, noise can cause organizations to make wildly divergent decisions based on factors that should not matter.

1: Noise vs. Bias – Two Sides of Error

A major lesson from the book is the distinction between noise and bias, and how both contribute to judgment errors. Bias is more frequently discussed and understood—it reflects a consistent deviation from the correct decision. Noise, on the other hand, is the random scatter of decisions. The book powerfully illustrates this with the metaphor of target shooting: while bias might consistently hit off-center, noise appears as a wide spread of shots across the board.

What makes this distinction so critical is that reducing bias doesn’t necessarily reduce noise. For example, if two doctors receive the same patient file and one diagnoses depression while the other leans toward anxiety, the disagreement isn’t due to bias—it’s noise. The lesson here is that addressing only bias gives a false sense of security; organizations must measure and address noise as well.

2: System Noise and Occasion Noise

The authors break down noise into components, with “system noise” and “occasion noise” being two key types. System noise arises when different professionals within the same organization make inconsistent decisions. Occasion noise refers to the variability in judgment within the same person across different times or contexts. For example, a judge might grant parole before lunch but deny it after, based purely on mood or hunger.

This theme exposes how personal factors—such as mood, weather, fatigue, or even recent sports results—can have irrational impacts on supposedly objective decisions. One lesson here is that even experts can’t reliably detect when they are affected by noise. Therefore, organizations must design systems that protect against this kind of variability.

3: The Human Mind as a Measuring Instrument

Kahneman and his co-authors treat human judgment as a form of measurement. Just like rulers or thermometers can be imprecise, so too can human judgments. Every decision we make—whether it’s estimating risk, evaluating performance, or making a diagnosis—is a kind of measurement. The issue is that humans are inherently noisy instruments. Two people using the same information may generate different results, which is deeply problematic in professions that rely on consistency.

A takeaway here is the importance of humility. If even experienced professionals—judges, doctors, executives—cannot consistently make similar judgments in similar circumstances, then overconfidence in human judgment is a flaw, not a virtue. Recognizing this encourages the use of tools that help reduce subjectivity.

4: The Cost of Noise

Another major lesson is the practical cost of noise. It’s not just a theoretical problem—it leads to financial waste, unfairness, and reputational damage. In one example, the authors discuss a noise audit in an insurance company. Executives believed that their underwriters varied by around 10% in setting premiums. In reality, the variation was around 55%. That kind of inconsistency can cost a company millions.

Whether it’s pricing risk, deciding whom to hire, or assessing creditworthiness, inconsistent judgments due to noise can lead to lost revenue, customer dissatisfaction, and inequality. The book emphasizes that identifying and measuring noise (via noise audits) is a necessary first step in any serious attempt to improve decision quality.

5: Decision Hygiene

One of the most actionable themes in the book is the introduction of “decision hygiene.” This refers to a set of practices designed to reduce noise in decision-making. Just like hygiene doesn’t guarantee perfect health but helps prevent disease, decision hygiene can’t eliminate all error but dramatically reduces noise.

Some strategies include:

- Structuring judgments: Using clear scales, criteria, and steps.

- Independent assessments: Getting multiple opinions before group discussion.

- Sequencing information: Presenting decision-relevant data in the same order for all judges.

- Noise audits: Measuring variation to identify inconsistencies.

This theme carries a key lesson: small procedural changes—like standardizing interview questions or separating assessment from discussion—can make a big difference in reducing noise.

6: Rules vs. Intuition

The book advocates for rules, algorithms, and structured guidelines over unaided human judgment, especially in high-stakes contexts. This can be a controversial theme, as many professionals prefer to trust their experience and intuition. But the authors show that statistical models are generally less noisy and more accurate than human judgments.

The lesson here is not to eliminate human decision-making but to augment it with tools that bring consistency. Structured rules, even when not perfect, tend to outperform experts over time because they reduce both bias and noise.

7: The Psychological Blind Spot to Noise

A particularly striking insight from the book is how little people recognize noise in their judgments. While we can often spot bias, we are blind to the variability of our own decisions or those of our colleagues. This creates an “illusion of agreement.” People in the same role may believe they are aligned because they share values and frameworks, yet when asked to make the same decision, their judgments differ significantly.

This theme teaches us the importance of self-skepticism. It urges decision-makers and organizations to challenge their assumptions about internal consistency and to routinely test for noise.

8: The Ethical Implications of Noise

Noise isn’t just inefficient—it’s unfair. When decisions like sentencing, hiring, or medical diagnoses vary depending on who’s judging or when they’re judging, individuals are not being treated equally. This can erode trust in institutions and cause real harm.

The ethical lesson is profound: justice, fairness, and equality are not only about eliminating bias; they are also about eliminating noise. Any system that allows large disparities in outcomes for similar cases is ethically flawed.

9: Acceptable Levels of Noise

Interestingly, the authors acknowledge that not all noise should be eliminated. Some variability may reflect genuine differences in values or context. Also, total standardization can make people feel dehumanized. There’s a trade-off between fairness, dignity, and efficiency.

The key lesson here is balance. Decision-makers must be clear about where noise is unacceptable—such as in legal sentencing or insurance pricing—and where some discretion is necessary or even desirable.

10: Collective Action to Reduce Noise

Finally, the book promotes a collective approach to reducing noise. It’s not enough for individuals to be aware of the problem—systems must be built to support better judgments. This includes everything from redesigning hiring processes to reforming legal sentencing to developing better medical guidelines.

The concluding lesson is that reducing noise is not just a technical fix—it’s a cultural shift. It requires institutions to prioritize fairness, transparency, and accountability in decision-making.

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment is a compelling call to action. It reveals a hidden dimension of human error that we’ve long ignored. By distinguishing noise from bias and showing its pervasiveness and cost, the authors make a strong case for taking it seriously. The themes of structured judgment, decision hygiene, ethical fairness, and system-level reform provide a roadmap for individuals and organizations alike.

In the end, the book teaches us that acknowledging our flaws—our noisy thinking—is not a weakness but a strength. It is the first step toward wiser, fairer, and more consistent decisions in a complex world.

Author’s Authority

There’s little doubt that the authors are authorities in their respective fields. Kahneman’s groundbreaking work on biases in human judgment earned him the Nobel Prize, and his earlier book Thinking, Fast and Slow became a modern classic. Sibony’s background in management consulting and decision science adds practical gravitas, while Sunstein’s experience in legal scholarship and public policy lends institutional weight to the discussion of regulation and organizational reform.

The combination of these perspectives gives the book unparalleled authority. However, some readers might wish for more concrete, step-by-step guidance on implementing noise-reduction techniques, as the book sometimes feels more diagnostic than prescriptive.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

One of the book’s most compelling strengths is its clear demonstration that noise is a neglected yet omnipresent flaw in human judgment. By illustrating this with powerful, real-world examples—such as the 55% variability among insurance underwriters estimating premiums for identical clients—the authors make the abstract concept of noise concrete and urgent.

The authors’ interdisciplinary approach is another standout feature. Combining Kahneman’s psychological expertise, Sibony’s management science insights, and Sunstein’s legal acumen, the book presents a holistic view of how noise affects decisions across diverse fields. This synthesis ensures that the lessons apply equally to judges, doctors, executives, and even everyday people.

Moreover, the introduction of “decision hygiene” as a practical toolkit for reducing noise is both innovative and actionable. Techniques like structured judgment processes, mediating assessments protocols (MAPs), and noise audits provide organizations with concrete strategies to improve their decision-making processes.

The authors’ transparent acknowledgment of the trade-offs involved in reducing noise is another strength. They wisely caution that the goal is not to eradicate noise entirely—which might dehumanize decision-making—but to bring it to an acceptable level that balances consistency with fairness.

Weaknesses

Despite its many strengths, the book occasionally suffers from repetitiveness. Some examples—particularly the insurance case study—are revisited multiple times, which can give parts of the book a circular feel.

Another shortcoming is the somewhat uneven balance between diagnosis and prescription. While the authors excel at identifying the problem and offering general solutions, readers may be left wanting more concrete, step-by-step guidance on implementing noise-reduction measures in specific contexts.

Furthermore, some critiques have emerged regarding the novelty of the concept itself. While the authors argue that noise has been overlooked, scholars familiar with measurement error or variability in decision-making might see the book as a repackaging of existing ideas rather than a groundbreaking new theory.

Lastly, the book’s emphasis on statistical approaches to noise—like noise audits and structured decision processes—might be off-putting to readers less comfortable with quantitative analysis. While the authors strive for accessibility, some sections might still feel dense to those without a background in statistics or behavioral economics.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence

Since its publication in May 2021, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment has garnered widespread acclaim, securing spots on both The New York Times Bestseller list and several other prominent lists. Critics have praised its rigorous scholarship and the urgency of its core message. As Bryan Appleyard of the Sunday Times put it, the book is a “monumental, gripping” exploration of how human judgment systematically fails in ways we have largely ignored.

The Financial Times lauded the book for its humbling lesson in inaccuracy, while The Times described it as a “rigorous approach to an important topic,” highlighting its ability to surprise and entertain as well as inform. Influential authors and academics, including Adam Grant and Angela Duckworth, have recommended it as essential reading for professionals seeking to improve decision-making.

However, not all responses have been unreservedly positive. Some critics have argued that the book’s core concept—that human judgment is noisy—was already well-known in fields such as measurement theory, where the problem is typically called “measurement error.” As a result, they question whether Noise offers genuinely new insights or simply repackages existing ideas in a more accessible form.

Moreover, the book’s emphasis on decision hygiene and structured processes has drawn some criticism from those who fear that such approaches might dehumanize decision-making, reducing complex human judgments to mechanical checklists. This tension is particularly evident in discussions about judicial sentencing, where critics worry that reducing noise could strip away important individual discretion and context.

Nonetheless, the authors acknowledge these trade-offs, emphasizing that the goal is not to eliminate all noise but to bring it to a manageable level that still allows room for human dignity and flexibility. They argue that organizations must prioritize noise audits and structured decision protocols to avoid the unacceptable human and economic costs that noise imposes.

In terms of influence, Noise has already sparked a new wave of interest in organizational decision-making, with many companies and public institutions beginning to adopt noise audits and structured judgment processes. The authors’ call for a new sub-science dedicated to analyzing and reducing noise may well shape the future of decision science for decades to come.

Quotations

To bring the insights of Noise to life, here are some of the book’s most compelling quotes that capture its essence and provide memorable takeaways:

“Wherever there is judgment, there is noise—and more of it than you think.”

This powerful statement encapsulates the central message of the book, reminding us that no matter the domain—law, medicine, business, or everyday life—human judgment is rarely as consistent as we’d like to believe.

“Noise in human judgment is a thoroughly prevalent and insufficiently addressed problem in matters of judgment.”

This quote reflects the authors’ core argument: that while bias has long been studied and managed, noise remains the overlooked flaw undermining decisions and fairness.

“The general property of noise is that you can recognize and measure it while knowing nothing about the target or bias.”

This observation highlights one of the book’s key practical points: even when the “correct answer” is unknown or unknowable, it’s still possible to measure noise by comparing different judgments of the same case.

“A defendant’s sentence should not depend on which judge the case happens to be assigned to.”

This quote underscores the moral urgency of addressing noise, especially in contexts like criminal sentencing where human lives are profoundly affected by inconsistency.

“Reducing noise does not mean eliminating it entirely—some level of noise is inevitable and sometimes even desirable to preserve human dignity and flexibility.

This balanced perspective is one of the book’s strengths, acknowledging the trade-offs involved in making judgments more consistent.

“Decision hygiene is like washing your hands: it may not be glamorous, but it is essential to avoiding the hidden threats that can undermine your decisions.”

This memorable metaphor captures the practical spirit of the book, encouraging readers to adopt systematic, preventive measures to reduce the impact of noise.

These quotations are not just rhetorical flourishes—they encapsulate the authors’ rigorous research, their practical recommendations, and their deep concern for the human and social costs of inconsistent decision-making.

Comparison with Similar Works by Other Authors

To fully appreciate Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, it’s helpful to place it in the broader landscape of behavioral science and decision-making literature. While Noise zeroes in on the underappreciated problem of unwanted variability in judgments, other works have explored related issues from different angles.

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Before Noise, Daniel Kahneman’s magnum opus Thinking, Fast and Slow revolutionized our understanding of cognitive biases. That book examined how humans systematically deviate from rationality due to mental shortcuts and intuitive judgments (System 1), contrasting with deliberate, analytical thinking (System 2). While Thinking, Fast and Slow focused on bias as the main source of judgment error, Noise complements it by highlighting inconsistency as another hidden, yet equally pervasive, flaw.

Nudge by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein

Cass Sunstein’s earlier collaboration with Richard Thaler in Nudge explored how subtle changes in choice architecture can steer people toward better decisions without restricting freedom.

Nudge emphasized predictable biases and designed solutions (nudges) to counteract them. By contrast, Noise broadens the lens to consider the variability in decisions even when choice architecture is consistent—a problem that nudges alone cannot fix. In this sense, Noise represents an evolution in Sunstein’s thinking, expanding from managing biases to managing noise as well.

Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner

Superforecasting delves into the art and science of making better predictions, highlighting the traits and techniques of exceptional forecasters.

Tetlock and Gardner emphasize calibration, accountability, and continuous updating to improve judgment. Noise, on the other hand, zooms in on the inconsistency between forecasters (and within the same forecaster over time) even when they follow best practices.

While Superforecasting suggests that better training and feedback can reduce judgment errors, Noise argues that systematic noise audits and decision hygiene protocols are essential for consistent improvements.

Blindspot by Mahzarin R. Banaji and Anthony G. Greenwald

This book tackles the hidden biases that shape our thinking and actions, often without our conscious awareness. Blindspot is primarily concerned with implicit biases that influence decisions in consistent, predictable ways. Noise distinguishes itself by showing that even when biases are absent, decisions can still vary randomly due to factors like mood, context, and interpersonal differences.

The two books together underscore that both bias and noise undermine the fairness and accuracy of human judgment.

Algorithms to Live By by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths

Christian and Griffiths explore how algorithms can inform and improve everyday decision-making. While Algorithms to Live By celebrates the power of structured, rule-based thinking, Noise emphasizes the problem of inconsistency in human judgment and the potential benefits of incorporating algorithms to reduce that noise.

Both books highlight the value of structured approaches, but Noise offers a more direct critique of human judgment’s inherent variability and the need for organizational solutions.

What sets Noise apart from these works is its singular focus on variability in judgment—the random scatter that makes even experienced professionals unreliable.

By proposing systematic tools like decision hygiene and noise audits, Noise provides a blueprint for addressing a dimension of human error that often flies under the radar. While other books have illuminated the cognitive biases and predictable errors that shape our thinking, Noise reveals the hidden chaos that emerges even in the absence of bias.

Together, these books provide a comprehensive roadmap for improving human judgment by addressing both the biases that steer us off course and the noise that makes our decisions scattershot.

Conclusion

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment is a profound and timely examination of one of the most neglected flaws in human decision-making. Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass Sunstein have crafted a compelling narrative that exposes how noise—unwanted variability in judgment—permeates every aspect of our lives, from courtrooms to hospitals, boardrooms to classrooms.

The book’s greatest strength lies in its meticulous presentation of empirical evidence. Through shocking examples like the 55% variation in insurance underwriters’ premium estimates and the striking differences in judicial sentencing, the authors drive home the point that noise is not a theoretical nuisance but a real-world problem with profound implications for fairness, health, and financial well-being.

Equally compelling is the authors’ prescription: decision hygiene. By adopting structured judgment processes, noise audits, and even algorithmic support, organizations can significantly reduce noise, leading to more consistent, equitable, and effective decisions. Yet, the authors wisely caution against eliminating noise entirely, recognizing the trade-offs involved—particularly the risk of dehumanizing judgment processes or undermining flexibility.

Among the book’s few weaknesses are occasional repetitiveness and a relative lack of step-by-step implementation guidance. Some readers might also argue that the concept of noise is not entirely novel; however, the authors’ unique synthesis of psychological, legal, and organizational perspectives gives the book a fresh and powerful voice.

In terms of audience, this book is essential reading for leaders, policymakers, judges, doctors, educators, and anyone who makes consequential decisions that affect others’ lives. It is also suitable for general readers interested in understanding how human judgment works—and often fails.

Ultimately, Noise is more than a book; it’s a call to action. By recognizing and addressing noise in our decisions, we can create fairer, more effective, and more humane institutions. It challenges us to rethink our confidence in human judgment and to embrace systematic approaches that enhance both consistency and justice. For anyone who values good decision-making, Noise is not just recommended—it’s indispensable.