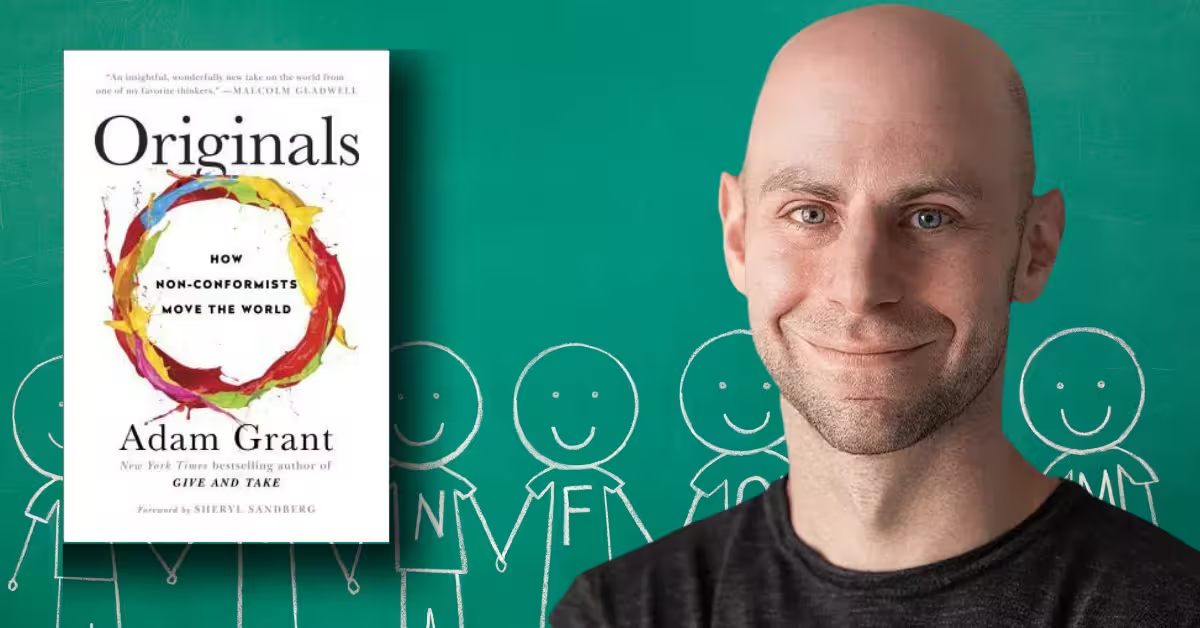

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World is a compelling exploration of creativity, innovation, and leadership by renowned organizational psychologist Adam Grant. First published in 2016, the book dives into the power of non-conformity and how individuals who break away from the norm make lasting impacts across industries, societies, and cultures.

Drawing upon Grant’s extensive research, the book merges real-world examples with psychology, sociology, and business strategy, making it a must-read for anyone interested in the mechanics of innovation.

This book is part of a growing body of work by Adam Grant, whose previous publications, including Give and Take, have challenged traditional thinking about success and leadership. In Originals, Grant challenges the myth that creative people are born, not made, and shows how anyone can foster originality.

The book targets entrepreneurs, managers, creatives, and individuals across the professional spectrum who are eager to make a difference by embracing unique ideas. Originals is a blend of storytelling, scientific research, and practical advice, presented in a clear and engaging manner.

Grant’s central thesis is that originality is not reserved for the chosen few, but can be cultivated by anyone willing to defy convention, challenge norms, and take calculated risks.

He dismantles the myth that non-conformists are simply born different and demonstrates how people can cultivate their own originality through specific behaviors and choices. From this, readers are encouraged to embrace their creativity and use it strategically to make an impact, both professionally and personally.

Table of Contents

Background

In this section, we explore Adam Grant’s academic background, which includes a Ph.D. in Organizational Psychology from the University of Michigan.

He has worked as a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and is a leading authority on the study of motivation, creativity, and leadership.

His research has been published in top journals, and he is also a TED speaker with millions of views. His books have shaped the way modern businesses approach culture, leadership, and success.

Grant’s work is deeply rooted in the application of psychological principles to real-world scenarios, and in Originals, he blends his expertise in organizational behavior with fascinating stories of cultural and technological innovation. His insights are backed by empirical evidence, making his arguments not only compelling but also actionable for individuals and organizations looking to foster innovation.

Summary

I found relevant content from the book you uploaded. I’ll now provide comprehensive summaries of the chapters you requested, starting with Chapter One and continuing in subsequent responses. Let’s begin with Chapter One:

Chapter One: Creative Destruction – The Risky Business of Going Against the Grain

Adam Grant opens Originals by examining the transformative power of creative destruction and the necessity of defying the status quo.

The chapter begins with a compelling example: the inception of Warby Parker, a company that revolutionized the eyewear industry by selling affordable glasses online, a concept that initially seemed impractical.

This entrepreneurial venture, led by a group of students burdened by loans and outdated eyewear, highlighted the risk of challenging a dominant industry player like Luxottica, which controlled over 80% of the market. Their journey exemplifies the central theme of the chapter: non-conformists take calculated risks to create meaningful change in industries resistant to disruption.

Grant uses this example to explore the broader concept of “creative destruction,” borrowing from economist Joseph Schumpeter’s idea that economic progress often requires breaking existing norms and conventions.

The founders of Warby Parker were criticized by their peers for their bold idea, but their determination to reject conventional wisdom ultimately led to success, with the company surpassing its sales expectations within its first year .

The chapter also addresses a common misconception about risk-taking. People often assume that entrepreneurs and innovators are risk-takers by nature. However, Grant presents research showing that successful non-conformists often practice a form of “calculated risk-taking” rather than sheer recklessness.

For example, studies show that entrepreneurs tend to be more risk-averse than investors or the general population, suggesting that their successes stem from careful preparation and strategic risk management .

In the latter part of the chapter, Grant reflects on the psychological challenges faced by original thinkers. Non-conformists often struggle with the emotional toll of being perceived as outliers, especially when their ideas face initial rejection. He argues that successful innovators are not immune to fear and self-doubt but rather learn to persevere despite it. By confronting their insecurities, these individuals can develop groundbreaking ideas that challenge existing paradigms .

The key takeaway from this chapter is that originality requires both courage and resilience. Grant emphasizes that creative destruction—upsetting the balance of an entrenched industry or system—is not for the faint of heart, but it is essential for progress. Innovators, by standing firm in the face of skepticism and adversity, pave the way for future advancements.

In the case of Warby Parker, their willingness to challenge the norms of eyewear retail disrupted an industry and introduced a new business model that redefined consumer expectations .

Chapter Two: Blind Inventors and One-Eyed Investors

In the second chapter of Originals, Adam Grant delves into the complexities of recognizing original ideas, highlighting the inherent challenges faced by both inventors and investors when evaluating innovation.

The title of the chapter, “Blind Inventors and One-Eyed Investors,” metaphorically refers to the cognitive biases that can cloud judgment, preventing people from accurately assessing novel ideas.

Grant begins by exploring the limitations of innovators when they are too emotionally invested in their ideas.

He uses the example of Dean Kamen, the inventor of the Segway, a product that was hailed as a game-changer in personal transportation. Despite the initial excitement and backing from industry giants like Steve Jobs and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the Segway ultimately failed to meet expectations. Grant explains that Kamen, much like many inventors, was too attached to his vision and unable to objectively assess whether the product was actually aligned with market demand.

Kamen’s overconfidence in the Segway led to the product’s failure, even though it was technologically groundbreaking.

The chapter introduces the concept of “cognitive bias,” specifically focusing on how inventors and entrepreneurs can fall prey to overconfidence in their ideas. Grant argues that inventors are often “blind” to the flaws in their own creations because they are so emotionally attached to them. They tend to overestimate the potential success of their products and overlook the market realities that might indicate otherwise. This overconfidence is often a result of an emotional connection to their work, making it difficult to recognize the shortcomings that others may easily see.

Similarly, Grant addresses the role of investors, who are often described as “one-eyed” in their ability to assess opportunities. Investors frequently rely on intuition and gut feelings when making decisions, which can lead to poor judgment, as seen with the example of Segway.

Despite the substantial investment from seasoned venture capitalists, the product’s success was far from guaranteed because of a misalignment between the technology and actual consumer needs. This highlights the difference between a good idea and a successful one — the latter requires more than just innovation; it demands a thorough understanding of the market and consumer behavior.

To navigate these biases, Grant introduces the importance of “outside perspectives.” He explains how investors and inventors can improve their decision-making processes by soliciting input from individuals who are not emotionally involved in the idea.

This “outside perspective” helps to bring a more realistic assessment to the table, allowing for a more accurate evaluation of the idea’s potential. For example, he discusses how one venture capitalist, who did not initially understand the comedic value of Seinfeld, was willing to take a risk on the show despite its initial poor reception in test audiences.

This decision ultimately paid off, as Seinfeld went on to become one of the most successful and influential TV shows in history.

Grant also discusses the role of “productive friction” in the process of idea selection. He suggests that when ideas face critical evaluation and challenge, they are more likely to succeed in the long run. The ability to embrace dissent and differing opinions from both investors and inventors is crucial for identifying the truly original and viable ideas.

This concept of productive friction is essential to counteracting the overconfidence that can cloud judgment and to ensure that ideas are rigorously tested before they are brought to market.

Through the examination of various case studies, including the rise and fall of the Segway, Grant illustrates that recognizing original ideas is not simply about having a good product. It’s about understanding the limitations, seeking diverse feedback, and being willing to adjust based on objective evaluations. Investors and inventors alike must be willing to question their assumptions and challenge their biases in order to identify truly revolutionary ideas.

The chapter closes with a powerful reminder: that true originality is not just about the ideas themselves, but about the rigorous, often uncomfortable process of selecting which ideas are worth pursuing.

Inventors need to detach themselves from their emotional attachment to their creations, while investors must learn to look beyond gut feelings and base their decisions on a broader understanding of the market and consumer needs. The combination of introspection, outside perspectives, and healthy debate is key to recognizing and nurturing truly original ideas.

Chapter Three: Out on a Limb

In Chapter Three of Originals, Adam Grant explores the theme of speaking truth to power, the courage to stand up for one’s beliefs, and the risks involved in advocating for original ideas within organizations or society at large.

The chapter, titled “Out on a Limb,” focuses on the personal and professional challenges that come with challenging authority, questioning the status quo, and promoting original, often controversial, ideas.

Grant opens the chapter with the story of a professor who stood up to a powerful academic institution and challenged established norms.

This professor, in the face of considerable pushback, advocated for a new way of thinking that had the potential to benefit both students and faculty. This example underscores one of the main points of the chapter: that to bring about meaningful change, individuals must often take personal and professional risks. The professor, despite knowing the likely consequences, was willing to go out on a limb and risk their reputation to push for progress.

The chapter highlights the psychological and social dynamics that make it difficult for individuals to speak up, especially when they feel their ideas may be unpopular or may provoke strong opposition.

Grant explains that one of the greatest barriers to originality is not the lack of ideas, but the fear of rejection or retaliation for proposing something that goes against the prevailing mindset. This fear often prevents people from taking the risks necessary to voice their original thoughts.

Grant introduces the concept of “courageous dissent,” explaining that standing out and speaking up often involves pushing back against not just authority figures but also the collective culture or norms within a group or organization. He discusses how leaders and innovators throughout history have often faced rejection and resistance for their beliefs, from political activists to scientists to business entrepreneurs. The chapter emphasizes the necessity of dissent in fostering progress and creating change, noting that those who bring about new ideas often face resistance from both their peers and superiors.

Through various case studies, Grant demonstrates how individuals who have spoken up at critical moments—despite the potential costs—have led to significant advancements in their respective fields.

For example, he examines the story of one of the earliest whistleblowers in the tech industry who, by daring to challenge the company’s practices, prevented widespread damage that could have harmed both consumers and the business in the long term.

Similarly, Grant reflects on the ways in which corporate whistleblowers and activists can influence policy change, despite the social and professional costs.

The chapter also discusses how people in positions of power are often resistant to hearing opposing viewpoints, even when those viewpoints are grounded in fact and logic. This resistance stems from both personal and institutional biases, as individuals in power often have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Grant draws upon research in social psychology, showing that those in authority positions are more likely to dismiss or downplay dissenting opinions, especially when they challenge long-standing beliefs or practices.

This can create an environment in which conformity is encouraged, and original ideas are suppressed.

Grant also delves into the practical strategies that individuals can use to voice original ideas and dissent without incurring significant professional risks. One such strategy is “preaching to the choir.”

Grant suggests that those advocating for new ideas should first seek support from allies within the organization or group—those who are more open to innovation and change. By gathering a coalition of like-minded individuals, innovators can build a more persuasive case and present a unified front, making it harder for their ideas to be dismissed outright. Grant emphasizes the importance of finding supportive allies in positions of influence, as these allies can help amplify the original idea and shield the innovator from backlash.

Another strategy discussed is “framing.” Grant explains how the way in which an idea is presented can significantly affect its reception.

Rather than simply challenging the status quo head-on, innovators can frame their ideas in a way that appeals to the values and goals of the audience. For example, instead of directly criticizing an organization’s policies, an innovator could frame their proposal as a means of improving efficiency or reducing costs. This approach allows the original idea to be seen not as a threat but as a solution to existing problems.

The chapter concludes by reflecting on the idea that speaking truth to power is not a one-time event but an ongoing process. Original thinkers must be prepared to continually challenge the norms and beliefs of their organizations and society, even when faced with adversity. The key to success, Grant argues, lies in persistence, strategic thinking, and the ability to navigate the social and professional risks that come with advocating for originality.

Grant’s central argument in Chapter Three is that originality often requires stepping outside of one’s comfort zone and challenging authority, whether it be within a professional setting, an academic environment, or society at large.

Those who have the courage to speak truth to power, to dissent against the norm, and to stand firm in their beliefs are the ones who drive innovation and progress. However, as the chapter makes clear, this is not without its risks. Original thinkers must be prepared to face resistance, both from individuals in positions of authority and from the broader culture.

Yet, as history shows, those who are willing to go out on a limb and challenge the prevailing norms are often the ones who create the most significant and lasting change.

Chapter Four: Fools Rush In

In Chapter Four of Originals, titled “Fools Rush In,” Adam Grant delves into the concept of timing when it comes to pursuing original ideas.

While many assume that being the first mover is the key to success, Grant argues that often it is not the boldest individuals who win, but those who are strategic in their timing. The chapter explores how being too quick to act can be as detrimental as waiting too long, highlighting the importance of patience and thoughtful decision-making in the process of bringing original ideas to life.

Grant begins with the example of two companies: one that rushed into the market with a new product without fully testing the waters and another that waited until the market conditions were just right. The first company, despite its innovative product, failed because it launched too soon, while the second company succeeded because it took the time to understand the market, gather feedback, and refine its offering. This dichotomy demonstrates one of the key themes of the chapter: that while speed can sometimes give a competitive advantage, it can also lead to mistakes and missed opportunities if not handled with care.

The chapter builds on the idea of “strategic procrastination.” Grant introduces research showing that procrastination is often unfairly stigmatized, when, in fact, it can sometimes be a powerful tool for achieving success.

He explains that individuals who delay their decisions, allowing time to gather more information and refine their ideas, are often more successful than those who rush to act.

By taking a more deliberate approach, innovators can avoid the common pitfalls associated with acting hastily, such as making premature decisions, missing key details, or misjudging market readiness. Strategic procrastination, in essence, allows people to weigh the pros and cons, gather feedback, and make better-informed decisions.

Grant also touches on the notion of the “first-mover advantage,” which is often celebrated as a hallmark of success in the business world. While it’s true that early entrants can sometimes dominate a market, Grant points out that being the first mover can come with significant disadvantages.

Pioneers are often forced to educate the market and incur high costs while figuring out what works. In contrast, followers can learn from the mistakes of the pioneers, avoid costly missteps, and enter the market with a more refined, tested product. Grant cites the example of Google, which entered the search engine market long after competitors like AltaVista and Yahoo!, but succeeded because it offered a superior user experience.

Google’s success was not due to being the first, but to the fact that it improved upon the existing product and understood what users wanted more effectively than its predecessors.

One of the critical points Grant makes in this chapter is that timing is often more important than being first.

By waiting for the right moment to act, innovators can capitalize on their competitors’ mistakes and enter a market with a stronger offering. This can be especially valuable in fast-moving industries, such as technology, where products and services evolve quickly.

Grant suggests that rather than rushing in with a half-baked idea, successful innovators tend to take their time to refine their product, seek out the right partnerships, and wait for the market to catch up with their vision.

To further emphasize the importance of timing, Grant draws on historical examples. He examines the cases of major innovators like Steve Jobs, who was famously not the first to introduce the personal computer or the smartphone, but succeeded by entering those markets at the right time with products that were superior to what already existed. Similarly, he discusses the success of Facebook, which grew to dominate social networking not by being the first social platform but by understanding the timing and needs of its audience more effectively than its predecessors like MySpace.

Grant also highlights the benefits of “waiting for the second wave” rather than rushing to be the first to market. He refers to the concept of “early adopters” and how they can be a double-edged sword. Early adopters often embrace new technologies and ideas, but they also tend to be more forgiving of flaws and imperfections. The majority of consumers, however, are more cautious and prefer to wait until a product has been proven in the market. Grant explains that successful innovators understand that they don’t need to cater to early adopters exclusively.

Instead, they can wait for the broader market to become interested, thereby reducing their risk and increasing their chances of success.

The chapter concludes by reiterating that while speed and boldness can sometimes be beneficial, they should be tempered by a willingness to delay action when necessary. Innovators who rush to market without considering the timing are often the ones who make avoidable mistakes.

On the other hand, those who practice strategic procrastination and wait for the right moment to act can make smarter, more impactful decisions. The ability to wait for the right time, assess the market, and refine an idea before launching is often the key to success.

Grant emphasizes that the best timing isn’t always about being the first to act but knowing when to act. The key is to be patient, gather enough information, learn from others’ experiences, and wait for the market to be ready for the idea.

Those who master this art of timing can avoid the pitfalls of premature action and set themselves up for long-term success.

Chapter Five: Goldilocks and the Trojan Horse

In Chapter Five of Originals, titled “Goldilocks and the Trojan Horse,” Adam Grant explores the dynamics of creating and maintaining coalitions to support original ideas.

The chapter examines how individuals with unconventional ideas can succeed by building alliances, especially when they face opposition from entrenched powers. The title refers to the well-known story of Goldilocks, where Goldilocks tests things until she finds the “just right” balance, and the Trojan Horse, symbolizing the subtle strategies used to infiltrate and influence groups from within.

Grant begins by introducing the idea that original thinkers rarely succeed on their own. Instead, they must gather support from others who can help them bring their ideas to life. The challenge, however, lies in persuading people who are resistant to change or uncomfortable with new ideas. In this context, Grant focuses on the power of coalition-building and the importance of making allies out of adversaries.

One key strategy Grant explores is the concept of “the Trojan Horse.” He uses the example of how leaders with original ideas can sometimes “sneak” their ideas into an organization or group by framing them in ways that align with existing goals, values, or ideologies.

This strategy can be particularly effective when proposing a radically different vision or approach. Rather than confronting the opposition head-on, the innovator can introduce their idea in a way that feels non-threatening and familiar, gradually winning over others who may have initially been skeptical.

This approach allows for the successful integration of original ideas without triggering immediate resistance.

The chapter also discusses the importance of finding “goldilocks” conditions—the perfect balance between being too radical or too conservative. Grant explains that ideas that are either too extreme or too safe tend to face rejection. To build a coalition, innovators must find a way to pitch their ideas that feels “just right” to a broad audience. They need to frame their proposals as reasonable and feasible while still offering something fresh and innovative. This balance is crucial in convincing others that the idea is worth supporting, especially when the idea challenges deeply ingrained beliefs or practices.

Grant highlights several examples of how effective coalition-building and the “Goldilocks principle” can lead to success.

He discusses how various social movements and corporate initiatives have flourished by framing their messages in ways that resonate with a diverse range of people. For example, the civil rights movement in the United States was able to gain widespread support by framing its goals as a fight for justice and equality, values that were deeply ingrained in American society.

Similarly, business leaders who proposed disruptive changes within their companies often found success by presenting their ideas in a way that aligned with the company’s broader mission and goals.

The chapter also touches on the role of strategic alliances in overcoming resistance to innovation. Grant discusses how, at times, it’s not enough to simply persuade a few key individuals to support an idea. Innovators must also be able to leverage the power of social networks and collective action. By building a broad coalition of supporters, individuals can amplify their message and create momentum for their ideas. Successful coalition-building requires empathy, understanding the concerns of others, and framing ideas in a way that addresses those concerns.

Grant also explores the notion of “strategic silence.” Innovators don’t always need to speak out or advocate for their ideas directly. Sometimes, it’s more effective to let others champion the idea for them. This approach can reduce the risks of backlash and increase the likelihood of gaining broader support.

Grant cites several examples of individuals who successfully influenced change by remaining in the background and allowing others to take the lead in advocating for the original idea.

The chapter concludes by emphasizing that coalition-building is an essential skill for anyone who wishes to bring about meaningful change. The ability to build alliances, to persuade others to support an original idea, and to find the right timing and approach is critical for success. Grant argues that, in many cases, the success of original ideas depends less on the ideas themselves and more on the social networks and coalitions that surround them. Innovators who are able to navigate the complex dynamics of group behavior, build trust, and gain support from a wide range of people are the ones who are most likely to succeed in making their visions a reality.

In summary, Chapter Five of Originals stresses the importance of coalition-building and strategic framing in achieving success for original ideas.

Innovators who can find the “Goldilocks” balance between radical and conservative approaches, frame their ideas in non-threatening ways, and build strong, diverse alliances are more likely to succeed in overcoming resistance and effecting meaningful change.

By using strategies like the Trojan Horse and strategic silence, individuals can subtly introduce their ideas and gain the support they need to bring them to fruition.

Chapter Six: Rebel with a Cause

In Chapter Six of Originals, titled “Rebel with a Cause,” Adam Grant delves into the influence of early life experiences—particularly family dynamics—in shaping the originality and rebelliousness of individuals.

Grant explores how having a supportive environment that nurtures curiosity and encourages non-conformity can lead to the development of original thinkers who challenge societal norms and inspire change. The chapter focuses on the role of siblings, parents, and mentors in fostering the rebellious spirit that drives innovation.

Grant begins by discussing the notion of “rebellion with a cause.” He emphasizes that not all rebels are created equal.

While some individuals rebel against authority or tradition for the sake of personal gain or attention, the most impactful originals are those who rebel with a clear sense of purpose—those who challenge the status quo not for the sake of defiance but in the pursuit of a higher ideal or a desire to create positive change.

This “rebel with a cause” mentality is often cultivated in childhood, where children are encouraged to think independently, challenge authority, and explore new ideas.

One of the central themes of the chapter is the influence of siblings on the development of originality.

Grant discusses how birth order can have a significant impact on a person’s likelihood to become a rebel or original thinker. He draws on research showing that firstborns tend to be more conscientious, responsible, and conformist, while later-born children often develop a more independent, rebellious streak. Later-born children are more likely to question established norms and seek novel solutions, which can foster creativity and innovation. This phenomenon is often referred to as “the sibling effect,” where the dynamics between siblings—such as competition or encouragement—shape the way individuals approach problem-solving and their willingness to challenge authority.

Grant also highlights the importance of parents and mentors in nurturing originality. He emphasizes that parents who encourage curiosity, exploration, and independent thinking are more likely to raise children who grow up to be original and creative.

Grant contrasts this with parents who prioritize obedience and conformity, as these children are less likely to develop the confidence and independence required to challenge the status quo. Mentors also play a critical role in this process.

A mentor who encourages critical thinking, allows space for experimentation, and provides guidance can significantly influence the development of an individual’s originality.

In addition to family dynamics, Grant discusses the impact of early exposure to diverse experiences. He argues that individuals who are exposed to a wide range of ideas, cultures, and disciplines during their formative years are more likely to develop the creativity and cognitive flexibility needed to think outside the box. This exposure allows individuals to draw connections between seemingly unrelated ideas, which is often the hallmark of originality.

The ability to integrate diverse perspectives and knowledge is essential for creating innovative solutions to complex problems.

Grant also explores how the concept of rebellion plays out in professional and academic settings. He examines the stories of several individuals who were able to disrupt industries or academic fields because they were willing to challenge prevailing theories or business models. These individuals, while often facing significant resistance and criticism, succeeded because they were not afraid to go against the grain and stand firm in their convictions.

They were rebels with a cause, driven by a deep sense of purpose and a commitment to making a meaningful impact.

The chapter concludes by emphasizing that rebellion, when channeled effectively, can be a powerful force for positive change. Grant argues that originality is not about rejecting authority for the sake of rebellion, but about questioning the status quo and striving to create something better. Those who rebel with a cause—who challenge norms in the service of innovation and progress—are the ones who shape the future.

In summary, Chapter Six of Originals highlights the role of family dynamics, mentorship, and early exposure to diverse experiences in shaping individuals who are capable of challenging the status quo and driving change.

The chapter emphasizes that the most impactful rebels are those who are motivated by a higher purpose—those who are not just defying authority, but seeking to create something new and better.

By fostering a spirit of curiosity, independence, and critical thinking, families, mentors, and experiences can play a crucial role in cultivating the next generation of original thinkers who will transform the world.

Chapter Seven: Rethinking Groupthink and Rocking the Boat and Keeping It Steady

In Chapter Seven of Originals, titled “Rethinking Groupthink and Rocking the Boat and Keeping It Steady,” Adam Grant explores the complexities of organizational culture and the interplay between conformity and originality within groups.

This chapter dives deep into the challenges and opportunities that arise when individuals attempt to introduce new ideas and challenge the status quo within a collective environment. The chapter is built around the concepts of groupthink, the desire for harmony and consensus within groups, and the need for dissent to foster creativity and innovation.

Grant begins by dissecting the common phenomenon of groupthink, where the desire for consensus in a group leads to poor decision-making and the suppression of dissenting opinions.

He explains that while harmony and cohesion are often valued in teams, they can come at the cost of original thinking. In highly cohesive groups, members tend to conform to the dominant view or the loudest voice in the room, even if it isn’t the best course of action. This phenomenon can be particularly dangerous when it stifles creativity and innovation. Grant suggests that organizations need to recognize the risks of groupthink and actively create spaces for dissent and diverse perspectives.

To illustrate the dangers of groupthink, Grant draws on the example of NASA’s decision-making process prior to the Challenger disaster.

The tragedy, where the space shuttle exploded shortly after launch in 1986, was the result of a failure to listen to dissenting opinions from engineers who had concerns about the O-rings in the cold weather. The engineers had warned that the shuttle’s components might not perform well in the low temperatures, but their concerns were dismissed in favor of maintaining the launch schedule and sticking to the status quo.

This failure to encourage dissenting voices and critically assess the risks led to a catastrophic outcome. Grant uses this example to underscore the critical importance of fostering an environment where dissent is not only tolerated but encouraged.

Next, Grant explores how dissent can be managed effectively within groups. He introduces the concept of “rocking the boat”—the idea that sometimes, shaking up the status quo is necessary to promote creative thinking and spur innovation.

However, he acknowledges that there are risks involved in challenging group norms. In order to successfully rock the boat, individuals must navigate the delicate balance of being disruptive without alienating others. Grant argues that it is essential to find the right time and manner to introduce alternative perspectives, ensuring that the dissent doesn’t come across as overly combative or destructive but instead as constructive and thought-provoking.

An important concept in this chapter is “psychological safety.” Grant emphasizes that in order for dissent to be effective, individuals must feel safe to voice their opinions without fear of retaliation or rejection.

Psychological safety is the belief that one will not be humiliated or penalized for offering an unpopular or critical idea. Grant presents research showing that teams with high levels of psychological safety are more innovative and perform better because they are able to engage in open, honest dialogue without the fear of being shut down.

In these environments, members are encouraged to share dissenting views, ask difficult questions, and propose radical ideas, knowing that their input will be valued rather than dismissed.

The chapter also touches on the importance of leaders in managing group dynamics. Grant asserts that leaders play a critical role in shaping organizational culture and influencing how dissent is handled.

Great leaders foster environments where employees feel empowered to speak up and challenge prevailing ideas, while also ensuring that differing opinions are not suppressed for the sake of harmony. One strategy Grant highlights is the role of the devil’s advocate, where leaders intentionally appoint someone to challenge ideas, identify weaknesses, and provide alternative viewpoints. This process can help ensure that decisions are thoroughly vetted and that new ideas are given fair consideration.

However, Grant also acknowledges that not all forms of dissent are productive. Some individuals may engage in “destructive dissent,” where their opposition to the group’s decisions or direction is driven by personal agendas, a desire for attention, or a reluctance to compromise. This kind of behavior can disrupt collaboration and damage group cohesion. Grant argues that it’s important to distinguish between constructive dissent, which seeks to improve the group’s outcomes, and destructive dissent, which undermines trust and cooperation.

Through a series of examples and case studies, Grant illustrates how organizations can manage the tension between dissent and group cohesion. He discusses companies like Google and Pixar, which have cultivated cultures of open communication and constructive dissent.

At these companies, employees are encouraged to share their opinions freely, but in ways that are respectful and focused on problem-solving rather than personal conflict. By fostering an environment where creative ideas can be debated and refined, these companies have been able to maintain their competitive edge and push the boundaries of innovation.

Grant also discusses the importance of cultural diversity in fostering originality. He argues that teams with diverse backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences are more likely to generate creative solutions because they are less prone to groupthink and more open to new ideas. While diverse teams can be more challenging to manage due to the potential for conflicting viewpoints, they are also more likely to produce innovative solutions that break from tradition.

The chapter concludes by offering practical advice for individuals who want to rock the boat in a way that encourages positive change.

Grant emphasizes the importance of timing and tact when introducing original ideas. He suggests that instead of immediately challenging authority or proposing drastic changes, individuals should start by building credibility, gathering evidence, and framing their ideas in a way that aligns with the group’s values and goals. Once they have established trust and rapport, they can more effectively present their ideas and inspire others to consider alternative perspectives.

In summary, Chapter Seven of Originals stresses the importance of managing group dynamics in a way that encourages dissent and diversity of thought while maintaining cohesion.

Grant highlights that organizations must actively work to prevent groupthink by creating environments where psychological safety is fostered, dissenting opinions are welcomed, and leaders model openness to new ideas. The key to balancing rocking the boat and keeping it steady is cultivating a culture where challenging the status quo is seen as a pathway to progress, not as a threat to harmony.

Chapter Eight: Rocking the Boat and Keeping It Steady

In the final chapter of Originals, titled “Rocking the Boat and Keeping It Steady,” Adam Grant explores the delicate balance between innovation and stability in organizations, teams, and cultures.

He discusses how individuals and leaders can manage the tension between shaking things up to introduce new ideas and maintaining the stability required for sustained success. The chapter focuses on how to foster an environment that embraces originality while also managing the emotions that accompany change, including anxiety, apathy, ambivalence, and anger.

Grant begins by acknowledging that when people challenge the status quo, they often face emotional and social resistance.

The fear of uncertainty, loss of control, and disruption of familiar systems can generate strong emotional reactions, such as anxiety or anger, from both those who are advocating for change and those who are resistant to it. These emotions can create significant barriers to introducing new ideas, particularly in established organizations with deeply ingrained practices and norms. However, Grant emphasizes that these emotional responses should not be seen as obstacles but as signals that indicate the need for careful management of the change process.

A key theme in this chapter is the psychology of change. Grant explores how people tend to react to change and new ideas based on their emotional attachment to the existing system.

Anxiety is one of the most common emotional responses to innovation because people fear the unknown and worry about the consequences of disrupting their routines or systems. Grant suggests that effective leaders must acknowledge these feelings and address them in a way that reassures individuals and reduces resistance. This can be done by clearly explaining the reasons for change, showing empathy for those who are apprehensive, and providing support during the transition.

At the same time, Grant discusses how apathy and ambivalence can also be significant challenges when introducing original ideas. Many people are not actively resistant to change, but they may be indifferent or disengaged because they do not see how the proposed changes will benefit them or improve their situation. To combat this, Grant suggests that innovators must be able to communicate the value and relevance of their ideas in a way that connects with the needs and motivations of others.

By demonstrating how new ideas can solve existing problems or lead to improvements, innovators can spark interest and enthusiasm.

Grant also explores anger as a natural reaction to change, particularly when people feel that their established power or status is being threatened. He notes that anger can sometimes be productive if it leads to constructive conversations and problem-solving. However, when anger is not managed effectively, it can lead to conflict and division within groups. Leaders, therefore, need to be skilled in navigating the emotional landscape of change and be able to address the concerns and frustrations that arise in a way that prevents destructive conflict and encourages collaboration.

The chapter moves on to discuss the role of leadership in managing the balance between rocking the boat and keeping it steady. Grant emphasizes that great leaders are not only innovators themselves but also cultivators of innovation in others.

They create environments where people feel safe to propose new ideas and challenge existing norms, while also ensuring that these ideas are tested and refined in a way that minimizes risk. Leaders can achieve this by fostering a culture of psychological safety, where employees feel free to speak up, share their ideas, and contribute to the change process without fear of ridicule or retaliation. This safety is essential for innovation, as it allows people to take the risks necessary to explore new possibilities without the emotional toll of fearing failure or rejection.

Grant also highlights the importance of managing group dynamics during periods of change. He advises that innovators should seek to build coalitions and gain support from a wide range of stakeholders.

By involving others in the process and giving them a sense of ownership over the change, innovators can reduce resistance and create a sense of shared purpose. This collaborative approach helps to maintain stability while still allowing for the introduction of new ideas.

Throughout the chapter, Grant uses examples from a wide range of fields, including business, politics, and social movements, to illustrate how successful innovators have managed to navigate the emotional challenges of change. One of the examples he discusses is the story of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose leadership of the Civil Rights Movement was marked by his ability to manage the tensions between challenging deeply entrenched systems of racial segregation and maintaining a sense of unity and purpose within his movement. King faced tremendous resistance, including violence and personal attacks, but he was able to channel these emotions into a constructive force that fueled the success of the movement.

Grant notes that King’s success came not only from his vision but from his ability to manage the emotional landscape of change and guide others through the inevitable turmoil that accompanies innovation.

The chapter concludes by emphasizing that innovation and stability are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the most successful organizations and movements are those that can balance the two.

Innovators who can challenge the status quo while maintaining the integrity and stability of the organization or movement will be better positioned to achieve lasting change. Grant argues that innovation is not just about disrupting systems but about finding ways to introduce new ideas in a way that preserves the values and strengths of the existing structure.

By carefully managing the emotional dynamics of change and fostering a culture of psychological safety and collaboration, leaders can create environments where originality thrives without destabilizing the foundation of the organization.

In summary, Chapter Eight of Originals explores the emotional and psychological aspects of innovation and change.

Grant emphasizes the importance of managing anxiety, apathy, ambivalence, and anger in the process of introducing new ideas. He argues that effective leaders must balance the need for innovation with the need for stability, creating environments where dissent is encouraged, and change can be implemented in a way that minimizes emotional resistance.

By fostering psychological safety, managing group dynamics, and building coalitions, innovators can introduce new ideas while maintaining the cohesion and stability needed for long-term success.

Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content:

Grant does an exceptional job of backing his arguments with a robust blend of research, case studies, and real-life examples.

The book’s evidence-based approach adds credibility to his claims about originality being within reach for anyone who takes a proactive approach to developing creative ideas. One of the standout elements is his explanation of how to foster originality, including steps like questioning defaults, creating the right environment for innovation, and embracing strategic procrastination.

However, at times, some of the examples feel a bit too idealized, such as the success stories of companies like Warby Parker and others that Grant uses to illustrate his points. While these examples are inspiring, they may overlook the broader challenges that come with being a non-conformist in industries resistant to change.

Style and Accessibility:

Grant’s writing is highly accessible, using anecdotes and clear language that make complex psychological theories understandable to a broad audience. He doesn’t shy away from sharing personal experiences, which helps to humanize the book and make it relatable. The flow of the book is well-structured, moving from theory to practical application without overwhelming the reader.

Themes and Relevance:

The book’s central themes of creativity, risk-taking, and strategic thinking are incredibly relevant in today’s rapidly evolving world. In a time when innovation is prized, Grant’s work offers timely insights into how individuals can embrace their own originality and overcome the constraints that often stifle creativity.

Author’s Authority:

As a professor at the prestigious Wharton School and a well-respected expert in organizational behavior, Grant’s authority on the subject is undeniable. His academic rigor, coupled with his practical experience, gives readers confidence in the reliability of his conclusions.

He also regularly collaborates with other leaders in psychology and business, further establishing his credibility.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

1. Comprehensive and Well-Researched: One of the key strengths of Originals is its robust foundation in research. Adam Grant, an expert in organizational psychology, provides extensive evidence to support his thesis, drawing from a wide range of studies and real-world examples.

The book is rich in both qualitative and quantitative data, making it a compelling read for those interested in the psychology behind creativity and non-conformity.

2. Actionable Advice: Grant’s writing is not just theoretical; it’s highly practical. He provides clear, actionable strategies for fostering originality, whether you are an entrepreneur, a manager, or an individual looking to make a difference.

Concepts like “strategic procrastination,” “questioning defaults,” and “building coalitions” are not only thought-provoking but also tangible steps readers can adopt in their own lives. These insights are presented in a manner that readers can easily relate to and implement.

3. Engaging Anecdotes and Real-World Examples: Throughout the book, Grant highlights stories of famous non-conformists, such as Steve Jobs, Martin Luther King Jr., and even lesser-known examples like the founders of Warby Parker.

These stories are not just inspiring, but also serve to illustrate how originality often involves resilience in the face of adversity. The use of real-world examples makes the theoretical concepts in the book accessible and relatable to readers from various fields.

4. Easy-to-Read Style: Grant has a knack for making complex psychological concepts digestible. His writing style is clear and engaging, making it suitable for a wide audience. Whether you’re a business leader, a student, or just someone interested in creativity, you will find the material easy to follow.

Grant also uses humor and personal anecdotes to break down complex ideas, further enhancing the readability of the book.

Weaknesses

1. Idealization of Success Stories: While the book offers powerful insights, some critics argue that it sometimes idealizes the success of non-conformists, especially entrepreneurs.

The book frequently focuses on examples like Warby Parker and other startup successes, which might not fully represent the struggles and setbacks that many entrepreneurs face.

This focus on successful case studies can potentially mislead readers into thinking that embracing originality will always lead to triumph, when in reality, many non-conformists face significant failures and challenges along the way.

2. Repetitive Concepts: Some readers have pointed out that certain themes and concepts in Originals are repeated throughout the chapters.

For example, Grant repeatedly emphasizes the importance of procrastination and the dangers of first-mover disadvantage. While these concepts are important, their frequent reiteration can occasionally make the book feel somewhat repetitive, especially for readers familiar with the basics of creativity and innovation.

3. Lack of Diverse Perspectives: Another critique is that the book could benefit from a wider range of perspectives, especially from individuals outside the American or entrepreneurial context.

While Grant’s examples are compelling, the emphasis on Western entrepreneurs and leaders may limit the book’s broader applicability, especially for readers in non-Western cultures or those in different industries. A more global perspective could have enriched the narrative and made it even more relevant to a diverse audience.

4. Oversimplification of Risk-Taking: Grant argues that originality doesn’t always require extreme risk-taking and advocates for a balanced approach to entrepreneurship. However, some critics feel that this downplays the role of calculated risk and boldness in achieving success.

While the book suggests ways to mitigate risk, it might not adequately address situations where bold risk-taking is necessary to succeed in highly competitive or fast-moving industries.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence

Reception

Originals has been widely praised by both critics and readers. The book has garnered attention from prestigious media outlets such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and BBC, who have all recognized Grant’s unique insights into the psychology of creativity and innovation.

Many praised the book for being timely, considering the rapidly evolving world of work and business. The way it challenges the status quo and redefines what it means to be “original” resonated deeply with entrepreneurs, educators, and professionals across various sectors.

Grant’s ability to combine rigorous academic research with engaging storytelling has made the book popular not only among scholars but also with general readers. Originals is often recommended by business leaders and thought influencers like Sheryl Sandberg, who contributed a foreword to the book, further solidifying its place as a key text on innovation and leadership.

Critical Reception: While Originals has been praised for its thought-provoking content, it has faced some criticism as well. As mentioned earlier, some readers find that the book presents a somewhat idealized view of originality.

Critics have also suggested that the focus on American entrepreneurs and leaders may not be applicable to readers from different cultural or business contexts. Additionally, some have noted that the book is not as groundbreaking as Grant’s previous work, Give and Take, which introduced a fresh perspective on networking and collaboration.

Despite these criticisms, Originals is still regarded as an insightful and impactful work that challenges conventional thinking and encourages readers to embrace their own creative potential.

Influence

The influence of Originals extends beyond the pages of the book. It has sparked discussions about creativity in the workplace, education systems, and leadership practices.

Many businesses and organizations have adopted Grant’s principles to foster a culture of originality, promoting environments where employees feel empowered to voice their ideas and challenge the status quo.

Educational institutions have also embraced the book’s themes, incorporating them into courses on entrepreneurship and leadership. Originals has become a standard reference in innovation and business strategy, with its insights being applied not just in startups but also in large corporations, government agencies, and even nonprofit organizations.

Grant’s emphasis on the importance of originality in every aspect of life has influenced individuals on a personal level, encouraging many to question their own default behaviors and step outside their comfort zones. The book’s impact is evident in the growing number of people and organizations that have actively worked to create more innovative and supportive environments for non-conformity.

Quotations

Throughout Originals, Adam Grant provides numerous thought-provoking quotes that capture the essence of his message. Here are a few key passages:

- “The hallmark of originality is rejecting the default and exploring whether a better option exists.”

- “Creative destruction is the risky business of going against the grain, but it’s also the key to making things better.”

- “What separates the originals from the copycats isn’t talent; it’s the willingness to take risks, make mistakes, and embrace failure.”

- “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”

These powerful quotes encapsulate the core themes of the book, encouraging readers to rethink what it means to be original and how to channel creativity into meaningful, lasting change.

Comparison with Similar Works

In comparison to other works in the field of creativity and innovation, Originals stands out for its focus on the psychology of non-conformity.

While books like The Lean Startup by Eric Ries and Zero to One by Peter Thiel focus more on practical strategies for building businesses, Originals offers a psychological framework for understanding and fostering creativity. It is more about how to think and what attitudes are necessary to embrace originality, whereas other books often focus on the what and how of executing ideas.

Grant’s work also stands apart from Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, which examines success through the lens of cultural and environmental factors. Whereas Outliers emphasizes how success is often determined by external factors, Originals emphasizes personal agency and the power of questioning defaults in order to drive change.

Conclusion

Summary of Impressions:

In Originals, Adam Grant provides readers with a comprehensive and thought-provoking examination of creativity, originality, and non-conformity. The book combines academic rigor with accessible storytelling, offering practical advice for anyone eager to challenge the status quo and make a difference in their personal or professional lives.

Recommendation:

For those interested in fostering creativity, challenging established norms, and cultivating originality, Originals is an essential read. It is suitable for a wide range of readers, from entrepreneurs to educators to professionals in any field.

Whether you’re looking to spark innovation in your workplace, raise creative children, or simply find the courage to be more original in your own life, this book provides both the inspiration and the tools you need to begin your journey.