Platoon (1986) is the rare Vietnam War movie that still feels like a bruise you keep touching, even when you know it will hurt.

Written and directed by Oliver Stone, it arrived in cinemas on 19 December 1986 as a war drama that refuses heroics. Instead of celebrating combat, it drags you through the mud with a young volunteer, Chris Taylor, and asks what happens to a conscience when survival becomes the only religion.

I keep coming back to it because it doesn’t just show a war; it shows the slow cracking of a person.

Its reputation is not just critical folklore: it won Best Picture at the Academy Awards, and the American Film Institute later placed it at number 86 on its 100 greatest American films list. On my own site, I also count Platoon as one of the 101 must-watch films, sitting alongside other war-adjacent classics like Apocalypse Now.

What follows is a spoiler-heavy retelling, because Platoon’s ending only lands when you feel how it earns its despair.

Table of Contents

Background

Stone wrote the screenplay out of his own time as an infantryman in Vietnam, and that personal stake is why the film’s details often feel observed rather than invented.

The production leaned into realism in ways that still matter: it shot in the Philippines, ran for a grueling 54 days, and cost roughly six million dollars.

When the US Department of Defense wouldn’t supply historically accurate gear, the film used equipment from the Armed Forces of the Philippines instead, which quietly underscores how messy “authenticity” can be.

The cast also went through an immersive 30-day military-style training course led by Vietnam veteran Dale Dye, complete with forced marches and night “ambushes.” Commercially, it broke out far beyond the art-house lane, grossing about $137.9 million domestically against that modest budget.

Decades later, the Library of Congress selected it for the National Film Registry, explicitly tying the film to cultural memory rather than mere entertainment.

Platoon is set in 1967, but it was made with the hindsight of a country still arguing with itself about what Vietnam meant and who paid the bill in bodies and broken minds. It helps to remember that the film isn’t trying to “explain” Vietnam so much as recreate the moral weather inside a single unit.

Now, with that context in place, let’s walk into the jungle.

Platoon Film Plot

Chris Taylor (played by Charlie Sheen) arrives in Vietnam in 1967 with the stubborn belief that volunteering is the same thing as understanding, and the heat corrects him almost immediately.

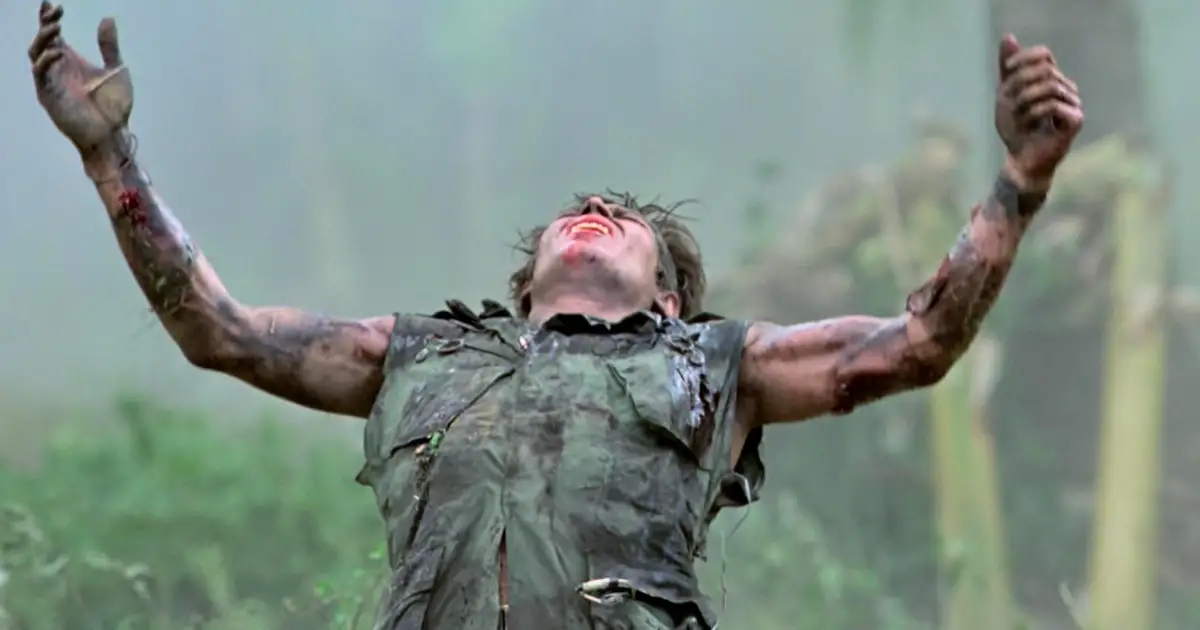

He is greeted not with glory but with logistics, exhaustion, and the cold vocabulary of a unit that calls fresh arrivals “new meat.” Taylor is folded into an infantry platoon where competence is survival and tenderness is treated like a dangerous luxury. Almost at once, he senses the platoon is split down an invisible fault line between two leaders: the brutal, mission-first Staff Sergeant Barnes (played by Tom Berenger) and the more humane Sergeant Elias (played by Willem Dafoe).

The early patrols are less “action” than attrition, with leeches, sweat, and fear doing as much damage as bullets. Taylor’s education is accelerated by small humiliations and sudden terror, the kind that arrives without warning and leaves the body buzzing long after the noise stops.

One night, on guard duty, Taylor’s fatigue becomes a weapon turned against his own side.

When the enemy finally appears in force, it is not cinematic clarity but chaos, and Taylor learns that bravery can look a lot like paralysis until somebody dies near enough to make it personal.

That personal turning point becomes the village sequence, where the platoon’s fear curdles into rage and moral boundaries start dissolving in real time.

Barnes drives the moment with suspicion and dominance, treating civilians as potential threats and punishment as a form of control. Elias pushes back, and the conflict isn’t abstract philosophy anymore because it plays out with rifles in hands and families watching. Taylor is caught in the middle, and the film is merciless about how “ordinary” people can slide into violence when the group’s appetite for blame gets louder than an individual’s conscience.

When the platoon leaves, it carries something worse than tactical uncertainty: it carries the knowledge that it crossed a line and kept walking.

After the village, Elias and Barnes stop being rivals and become opposing verdicts about what kind of men they are. On a later operation, Taylor witnesses the moment the platoon’s internal war turns lethal, as Elias is betrayed and abandoned, and his death becomes the unit’s unhealed wound.

With Elias gone, the platoon doesn’t “move on” so much as rot from the inside, and Taylor starts measuring men not by rank but by what they are willing to do when nobody is watching.

He tries to narrate his experience like a letter home, but the longer he stays, the less language helps, because language implies order and Vietnam keeps refusing to provide it. The soldiers around him talk about “fragging” Barnes as if murder could be a form of hygiene, a way to disinfect the platoon of the worst version of itself.

Taylor is pulled toward the plot not because he is inherently violent, but because the film shows how exhaustion can make even decency feel like a burden you can’t afford to carry.

Barnes senses the danger and retaliates, violently reminding Taylor that in this environment power is enforced at arm’s length and sometimes at knife’s edge.

The climax arrives as a full-scale night assault, and the movie’s earlier moral tension is swallowed by raw survival as bodies drop and the perimeter collapses.

A suicide attack tears into the battalion’s command area, the night becom

es a storm of smoke and screaming, and the platoon’s internal politics are suddenly irrelevant next to the simple fact of being overrun.

Taylor is wounded and disoriented, pinned between enemy fire and the terrible randomness of support strikes that can save you or erase you.

In the middle of that carnage, Barnes reappears like the embodiment of everything the film has been warning about, and the confrontation between him and Taylor becomes both personal and symbolic.

Taylor kills Barnes, and the act lands with no triumph at all, only the numb understanding that Vietnam has finally taught him its ugliest lesson: sometimes you survive by becoming what you hate.

The ending pulls back from the battlefield into evacuation, where Taylor is lifted out while others remain trapped in the same cycle of fear, loyalty, and damage.

His closing reflection frames the film’s thesis in human terms: the platoon fought the enemy, yes, but it also fought itself, and the “real” wound is the one you carry home.

Platoon Analysis

The more I sit with Platoon (1986), the more it feels like a film that doesn’t want applause so much as it wants an honest flinch.

Oliver Stone’s direction has a bruised, first-hand urgency, and you can feel him steering the story like someone who remembers the heat and the fear rather than someone composing “war movie” tableaux.

What lands hardest for me is how the performances create a living ecosystem of stress, boredom, cruelty, and sudden tenderness.

Charlie Sheen’s Chris Taylor works as an entry point because he looks like he still believes the world is readable, while Willem Dafoe and Tom Berenger embody a moral split that the platoon can’t keep contained.

It’s also telling that the film’s awards conversation wasn’t only about spectacle, because Dafoe and Berenger both earned Academy Award nominations for their supporting roles.

Stone’s script is sharpest when it lets contradiction stand without rushing to explain it away, and it helps that the dialogue often sounds like men speaking to stay sane rather than to sound quotable.

The soundscape is doing more emotional work than it gets credit for, especially once Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” enters and makes grief feel almost physical.

Platoon Film Themes

War in Platoon (1986) is shown as a battle inside the platoon as much as a battle against the North Vietnamese Army, with Barnes and Elias embodying two competing ways to survive.

- The platoon’s “civil war” (morality vs survival): I read the Barnes–Elias split as the film’s central argument about what war rewards. It’s not just personality conflict, because the unit is visibly divided into cliques who cope differently (“heads” versus Barnes’s hard-edged followers). The result is a war film where the closest threat is sometimes the man standing beside you.

- Moral collapse and the normalization of atrocity: The village sequence is the clearest picture of ethics degrading under pressure—interrogation, threats, murder, and the attempted sexual violence Taylor tries to stop.

- Civilians trapped in someone else’s fear: The film keeps showing how easily “suspect” becomes “target” when a platoon is desperate for control.

- Leadership as moral weather: A young, inexperienced lieutenant leaning on seasoned NCOs creates a vacuum where the harshest personality can define what is “acceptable.”

- Chaos, misfire, and the randomness of death: Even the machinery of war is unreliable, like the moment artillery is accidentally directed onto the unit, turning “support” into another hazard.

- Brotherhood and betrayal in the same breath: The film understands that camaraderie can be real, but also conditional, and sometimes weaponized—especially once Elias is eliminated and the platoon’s trust breaks apart. I see the “heads” circle as a fragile attempt to preserve softness, while Barnes’s circle offers the security of intimidation, and both are coping mechanisms rather than solutions. When Taylor starts talking about fragging Barnes, it’s not presented as justice so much as infection: violence as the only language left. The movie’s tragedy is that the platoon doesn’t just lose men; it loses a shared reality. And once that happens, “comrade” becomes a role you can revoke.

- Trauma that doesn’t end at extraction: The final image of Taylor sobbing as he’s carried away makes the point I feel in my gut every time—survival is not the same as being okay.

- Storytelling as a political act (and a contested one): Even outside the film’s world, its themes land like a dispute, shown by the Department of Defense refusing support over what it saw as an unfavorable depiction of American soldiers and war crimes, and by the later criticism about racial stereotyping.

Theme-wise, Platoon keeps circling one brutal question: what does war turn ordinary people into when no one is watching, and when everyone is watching, and when the two blur.

There’s a blunt production detail that frames this discomfort: the US Department of Defense refused to support the film because of its depiction of American war crimes, and that refusal itself tells you how incendiary the story was considered.

Stone doesn’t treat the platoon as a single unit with a single conscience, and that’s why Barnes and Elias feel like more than characters, because they’re competing definitions of survival.

The film’s social commentary also runs through class and race tensions inside the unit, not as a “lesson,” but as a pressure that war intensifies rather than erases.

When I watch it now, the message that sticks is that moral injury isn’t only about what happens to you, but also about what you do, what you allow, and what you become capable of excusing.

Comparison

If you place it beside other Vietnam War films like Apocalypse Now or The Deer Hunter, Platoon feels less mythic and more ground-level, like it’s allergic to turning trauma into poetry.

That difference is part of what sets it apart, and it’s why critics and audiences often describe it as visceral rather than operatic.

For a film this harsh, it’s striking how well it still connects with viewers who come to it for both history and human conflict.

Even beyond its story, Platoon (1986) has the kind of cultural footprint that signals it crossed over from “successful movie” into “reference point.”

Awards

At the 59th Academy Awards, the Academy’s own recap notes that Platoon won Best Picture, and also won Oscars for Directing (Oliver Stone), Film Editing, and Sound.

Its long-term recognition goes beyond trophies, too, because the Library of Congress lists Platoon (1986) as being added to the National Film Registry in 2019. That kind of selection is a signal that the film is treated as culturally significant, not just commercially successful.

Financially, the box-office record is just as blunt: Box Office Mojo lists a $6 million budget and a domestic gross over $138 million, while The Numbers reports similar scale across domestic and worldwide totals.

And yes, I’m also framing it here as one of the 101 must-watch films, because your own list on probinism.com includes “Platoon (1986)” in the lineup.

Who is this film really for today, and who might want to skip it. If you’re drawn to Vietnam War cinema, anti-war dramas, or character-driven stories where morality fractures under pressure, it’s an essential watch.

If you’re a casual viewer looking for clean heroism or easy catharsis, this one can feel punishing, because it refuses to protect you from what it’s showing. Rotten Tomatoes labels it R and lists the runtime at 2 hours, and the content earns that rating through brutal violence and disturbing scenes rather than cheap thrills.

Metacritic also presents it as an R-rated film, and that’s worth treating as a real viewer warning, not background metadata.

Reception-wise, it’s one of those rare war movies that is both widely acclaimed and still argued over in meaningful ways, with Rotten Tomatoes showing an 89% Tomatometer and Metacritic listing a 92 Metascore.

6. Personal Insight and lessons

I did not leave Platoon feeling educated about strategy, and that is exactly why it still matters.

When I rewatch it now, the most frightening part is not the firefight but the quiet permission people give themselves to stop caring.

That “permission” is what makes the movie feel like a Vietnam war film and a leadership failure story. It is also why I still keep it on my “101 Best Films You Need to See” hub page.

Platoon keeps reminding me that violence is not only something done to you, it is also something you can slowly learn to do. The film makes that lesson unbearable by showing how fast “normal” shrinks to whatever you can survive.

The war-movie cliché is that fear makes you brave.

What Platoon suggests is that fear makes you programmable.

I think about “moral injury” whenever I return to this film, because the damage here is not only terror but also the feeling that your own values have been bent past repair.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs describes moral injury as distress tied to events that violate deeply held morals or values.

In Platoon, that violation is not abstract, because it plays out in front of witnesses who cannot unsee what they saw. The movie also shows how people cope by turning away, turning numb, or turning cruel, and none of those strategies lasts.

That is why the Barnes-and-Elias split still lands like a personal argument rather than a plot device. One side offers certainty and survival, and the other side offers restraint and a fragile kind of dignity.

I hear Chris Taylor’s narration now as an adult trying to rescue the younger self who volunteered.

The film’s Vietnam is also a class story, and that angle has only sharpened as inequality has become a daily headline.

When Chris talks about who ends up in the mud, I cannot avoid thinking about how easily societies outsource risk to the people with the fewest exits.

That thought makes Platoon feel less like a period piece and more like a mirror held up to every “necessary” sacrifice we ask strangers to make.

It also helps explain why the movie keeps being taught and argued about, even by viewers who never seek out war films for fun.

Even in civilian life, the movie reads like an essay on leadership and permission. If you have ever worked under someone who rewards aggression, you already understand a small version of how moral weather changes a room.

The scariest scenes are the ones where the platoon becomes a committee that votes on cruelty.

I also keep coming back to the way sound becomes memory in this film.

The Wikipedia summary of the film’s music notes that the score is by Georges Delerue and that the movie uses Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings,” alongside period songs like “White Rabbit” and “Okie from Muskogee.”

When that cue rises, the story stops being about the jungle and becomes about the afterlife of the jungle inside a person.

There is a strange kindness in how the music slows the film down, as if it gives the viewer permission to grieve rather than just react.

It is the sound of the film asking you to mourn, not to cheer.

If you want a present-day takeaway, it is this: leadership failures do not stay at the top, and they drip down until ordinary people start acting like the worst version of the rules they have been given.

Platoon leaves me believing that rebuilding after violence is possible, but only if we tell the truth about what we did and what was done to us.

Cast:

- Charlie Sheen as Chris Taylor – the idealistic volunteer whose loss of innocence drives the emotional core of Platoon (1986)

- Tom Berenger as Staff Sergeant Barnes – the ruthless, battle-hardened leader who believes survival justifies brutality

- Willem Dafoe as Sergeant Elias – the moral conscience of the platoon, representing compassion in an inhumane war

- Keith David as King – a calm, authoritative presence offering guidance amid chaos

- Forest Whitaker as Big Harold – a deeply human portrayal of fear, vulnerability, and inner conflict

- Francesco Quinn as Rhah – one of the younger soldiers reflecting the platoon’s emotional instability

- Kevin Dillon as Bunny – an aggressive, volatile figure who thrives in the lawlessness of war

- John C. McGinley as Sergeant O’Neill – a struggling non-commissioned officer battling insecurity and pressure

- Reggie Johnson as Junior – a soldier whose psychological breakdown highlights war’s mental toll

- Mark Moses as Lieutenant Wolfe – a junior officer overwhelmed by command and moral responsibility

- Corey Glover as Francis – part of the platoon’s inner circle, reflecting racial and social dynamics

- Johnny Depp as Lerner – a brief but memorable role capturing youthful detachment and fragility

- Chris Pedersen as Crawford – a pragmatic soldier focused on survival rather than ideology

- Bob Orwig as Gardner – a supporting presence adding realism to the platoon ensemble

- Corkey Ford as Manny – one of the many faces shaped by exhaustion and constant danger

- David Neidorf as Tex – a hardened soldier representing instinct-driven survival

- Richard Edson as Sal – contributing to the platoon’s volatile emotional landscape

- Tony Todd as Warren – a powerful screen presence in a supporting role

- Dale Dye as Captain Harris – portrayed by a real Vietnam War veteran, adding authenticity and authority

Platoon Film Quotes

“I think now, looking back, we did not fight the enemy, we fought ourselves”.

That line is the film’s thesis in plain English, and it lands harder because it arrives after so much noise. It refuses the comfort of a clean villain, and it makes self-examination the final battleground. When I hear it, I think less about Vietnam as history and more about the quiet wars people carry home.

“Hell is the impossibility of reason”. That is the most accurate definition of a bad day that never ends.

“Shut up and take the pain”.

In that moment, pain becomes a policy rather than a feeling.

“There are times since, I’ve felt like a child, born of those two fathers”. That line turns the platoon into a broken family and the war into inherited damage.

It hints at moral injury before the term was popular, because it shows identity being rewritten by what you witness and what you do. It also explains why the film’s violence feels psychological as much as physical.

In that sense, the quote works like a summary of the ending, because it describes a survivor who is permanently split. I read it as the film’s quiet admission that the battlefield follows you, even when you leave the battlefield.

If a war film can make you think and flinch at the same time, it has probably told the truth.

Pros and Cons

I can praise Platoon without pretending it is painless to sit through.

For me, its biggest strength is the refusal to glamorize combat, even when the cinematography is beautiful. Another strength is how lived-in the performances feel, which keeps the movie from drifting into “message movie” territory. And the sound and music choices turn scenes into memory scars.

Its biggest weakness is that the emotional pressure can feel relentless, with little air between shocks. Some viewers will bounce off that intensity even if they respect the film.

Here is my quick breakdown.

Pros and cons are easier to read when they are blunt.

- Pros — Ground-level realism that avoids glamorizing violence

- Pros — Performances that feel lived-in rather than performed

- Pros — Music cues that lock the grief into place

- Cons — Unrelenting intensity for sensitive viewers

- Cons — Certain portrayals invite criticism and debate (worth reading alongside the film)

Conclusion

By reputable reference accounts, Platoon is also a major awards-era benchmark and continues to be treated as one of the defining Vietnam films.

It was also selected for the US National Film Registry in 2019, which is a strong signal of its ongoing cultural footprint.

If you can handle an unvarnished war film, I still recommend it as essential viewing, but I would not call it “enjoyable” so much as necessary.

Rating

4.5/5