Last updated on May 13th, 2025 at 10:51 am

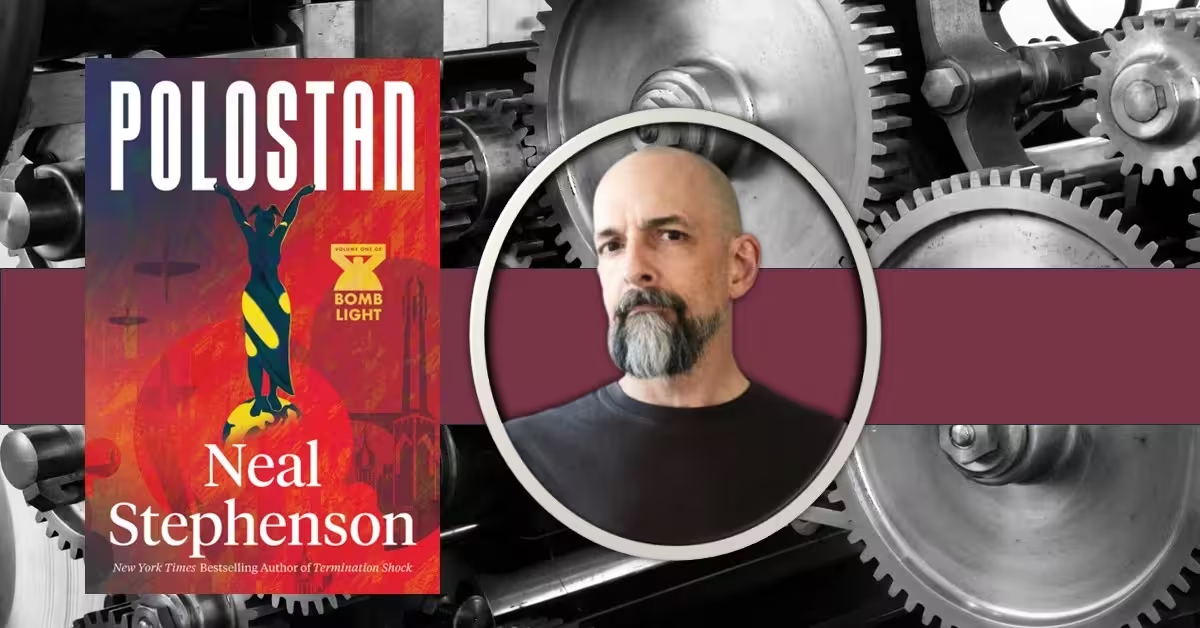

Polostan by Neal Stephenson is a sprawling, genre-bending historical novel that once again solidifies Stephenson’s place as one of the most daringly ambitious writers of our time. Known for his deeply intellectual works such as Cryptonomicon and Anathem, Stephenson returns to familiar territory—an intricate entanglement of science, ideology, and power—but through a surprisingly intimate lens in Polostan.

First published in 2024, the book is already garnering attention for its complexity and unflinching analysis of Soviet ambition, American industrialism, and human desire for meaning.

A blend of speculative fiction, political thriller, and literary satire, Polostan is set in the tumultuous 1930s across Soviet Russia and the United States. From Magnitogorsk to Chicago, the novel explores the intersections of war, ideology, propaganda, and gender dynamics, all filtered through the surreal metaphor of a sport—polo—played on shifting political landscapes. In classic Stephenson fashion, the novel is peppered with deep dives into physics, history, linguistics, and military maneuvering, but Polostan surprises readers by being more character-driven than some of his previous work.

Neal Stephenson is no stranger to dissecting power structures. With academic precision and imaginative brilliance, he crafts Polostan not just as a novel but as a thesis—on revolution, reinvention, and repression. And unlike his previous heavy tomes, this work breathes with unexpected tenderness.

At its core, Polostan by Neal Stephenson is an exploration of constructed realities—how regimes fabricate purpose, how individuals script their own myths, and how identity is both weapon and refuge. The central thesis can be distilled from a key exchange between protagonist Aurora and her father:

“To agree that Patton had only been making a fool of her was to strip herself of that dignity and purpose. She might accept the loss of a ball gown but not of that”.

The book argues that ideology, whether Communist or capitalist, cannot replace the deeper existential hunger for agency, recognition, and connection. That’s what makes Polostan more than political satire or historical commentary—it becomes a deeply human novel.

Table of Contents

Plot Summary of Polostan

Set in a turbulent 1930s world, Polostan tells the sweeping story of Aurora “Dawn” Artemyeva, a young woman with dual roots in Russia and America, whose life becomes an odyssey across continents and ideologies.

The novel opens with a prologue at the Golden Gate Bridge construction site in San Francisco, where Bob, an American engineer, meets Dawn — now calling herself Aurora — after years apart. In the depths of the Great Depression, both are seeking meaning beyond the capitalist decay they witness. Bob, working on America’s proudest infrastructure project, is nevertheless disillusioned with his country. Aurora, matured through hardship, proposes a bold idea: they should both travel to the Soviet Union, to the vast steel-making city of Magnitogorsk, where Bob’s expertise and Aurora’s fluency in Russian could serve the cause of socialism.

Accepting the call, Bob and Aurora leave behind a crumbling America and venture to Magnitogorsk, a half-built industrial giant on the Siberian frontier. There, amid brutal cold, scarcity, and ideological fervor, Aurora embeds herself among the workers, witnessing firsthand the clash between utopian dreams and harrowing realities. On Christmas Eve 1933, she climbs the icy scaffolds of Blast Furnace #4 with her Shock Brigade, a volunteer work group pushing Soviet industry forward despite overwhelming hardship and frequent deaths.

Through Aurora’s eyes, the novel immerses readers in the chaos of Soviet industrialization: the desperate improvisations of workers, the surveillance and paranoia of the secret police (OGPU), and the constant pressure to perform, survive, or be denounced as a wrecker. Yet even in the bleakness, there is camaraderie, determination, and flashes of humor — a sense that ordinary people are struggling toward something larger than themselves.

Interwoven with the main narrative are vivid flashbacks to Aurora’s childhood in Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) after the Russian Revolution. As a young girl, she navigates the communal living of a kommunalka, the propaganda of the early Soviet school system, and the emotional wounds left by her parents’ ideological divides. Her American mother, longing for the open spaces of Montana, ultimately leaves the Soviet Union, while her father, a devout communist, remains and reshapes Aurora’s identity around the ideals of the Revolution. It is in these early years that Aurora first internalizes both the promises and the contradictions of socialism.

As the story unfolds, Bob’s technical genius and Aurora’s linguistic and political skills position them within the Soviet hierarchy. However, they must constantly balance the dream of building a better future against the brutal realities of life under Stalinist rule — where suspicion, betrayal, and terror loom larger than any utopian ambition.

The final parts of the novel follow the transformation of Magnitogorsk into a grim monument to forced progress, and Aurora’s growing disillusionment. Despite her youthful hope, she sees that the machinery of Soviet power crushes not only the enemies of the Revolution but often its own most devoted children. In the end, the promised land of socialism — Polostan — turns out to be a place of ghosts, ash, and lost ideals.

Alright! Let’s continue, deepening the Plot Summary of Polostan while keeping it all under the same heading — still Wikipedia-style, natural storytelling.

I’ll pick up from where we left off, expanding through major episodes like Magnitogorsk, Chicago, North Dakota, and the final transformation into Polostan.

After arriving in Magnitogorsk, Aurora and Bob quickly realize the immense gap between Soviet propaganda and the grim, cold reality. The city, envisioned as the centerpiece of Stalin’s Five-Year Plan, is little more than a chaotic, half-finished sprawl of mud, steel, and deprivation. Workers live in tents and shacks amidst subzero temperatures, eking out survival as they labor under impossible quotas. Infrastructure is skeletal, food is scarce, and basic equipment like tools and safety gear are missing or improvised. Even so, the enthusiasm for building socialism burns brightly among some — and Aurora, committed and hardened, throws herself into the struggle.

Aurora joins a Shock Brigade, a group of volunteer workers meant to set examples of heroic productivity. In one harrowing episode, she and her comrades — including the dignified prisoner-engineer Fizmatov and the ever-watchful agitator Tishenko — must climb an ice-crusted scaffold around Blast Furnace #4 to clear a blockage. In this moment, Stephenson shows the terrifying physicality of Soviet labor: frostbite, broken tools, and casual death. When a fellow worker freezes to death clinging to his welder for warmth, the event barely causes a ripple. Progress must continue. Lives are disposable in the machinery of Stalinist modernization.

Interspersed are flashbacks to Aurora’s childhood in Petrograd, where she grew up during the civil war aftermath. There, in crowded communal apartments, she learned survival and indoctrination. Her American mother eventually fled back to Montana, disillusioned, while her communist father raised her on Leninist ideals, renaming her Aurora after the battleship that had launched the October Revolution. As a child, she participated in games like razverstka, role-playing the seizure of grain from kulaks — a chilling foreshadowing of the real purges to come.

Back in Magnitogorsk, Aurora matures quickly. Her observations of the system grow sharper: bureaucratic corruption is rampant, and ideological fervor often masks incompetence and cruelty. The workers’ supposed paradise is riddled with starvation, informants, and secret arrests. Despite her deep-seated belief in socialism’s promise, Aurora increasingly sees that idealism is weaponized against the very people it claims to uplift.

Parallel to Aurora’s Soviet experience, Bob’s story stretches across the United States, where flashbacks reveal his journey through Depression-era Chicago. There, the collapse of capitalism is just as visible — in soup lines, tent cities, and the violent suppression of labor uprisings. Working in industrial steel mills, Bob becomes disillusioned with America’s empty promises of prosperity and fairness. His growing sense of betrayal fuels his willingness to gamble everything on the Soviet experiment.

The novel’s middle sections shift between Magnitogorsk and America, highlighting the mirrored failures of both systems: capitalism mired in greed and inequality; socialism collapsing into paranoia and authoritarianism.

As time passes, Aurora’s idealism is battered but not fully extinguished. After witnessing repeated abuses and betrayals, she makes a fateful decision: to continue eastward, toward the even deeper heartlands of the Soviet dream.

Meanwhile, Bob, exhausted and morally adrift, seeks a way out. Their paths, once intertwined, begin to diverge. The steel that was supposed to forge a new world becomes, instead, a symbol of unbending ideological rigidity — cold, unforgiving, and inhuman.

In the novel’s final act, Aurora reaches Polostan, the Soviet dream city hidden deep beyond the Urals, intended to be a pure socialist utopia — free from the corruption and errors of the early industrial cities like Magnitogorsk. Yet when she arrives, it is clear that Polostan is not a paradise but a brutal experiment in social engineering. Surveillance is total. Betrayal is routine. Death comes quietly in the night. Hope is traded for survival.

In a devastating culmination, Aurora realizes that Polostan itself was a lie — a Potemkin village of ideology, built on the bodies of the forgotten. The story closes not with triumph, but with a grim understanding: that both America and the Soviet Union, for all their differing ideologies, are capable of devouring their idealists.

Aurora, alone but unbroken, becomes a wanderer between worlds — too Russian for America, too American for Russia, and too disillusioned for any ideology at all. Her journey, from the muddy rail lines of San Francisco to the frozen tundra of Polostan, becomes a story of hope corrupted, endurance tested, and humanity stripped bare, revealing the inescapable costs of building utopias on fragile human dreams.

Main Characters in Polostan

Aurora “Dawn” Artemyeva

The novel’s protagonist, Aurora — originally named Dawn — is a young woman of dual American and Russian heritage. Raised amid the ideological zeal of post-revolutionary Petrograd and later shaped by the harshness of Depression-era America, she embodies the clash of utopian dreams and brutal realities. Fluent in Russian and English, resilient yet deeply idealistic, Aurora seeks to build socialism’s promised future in Magnitogorsk and later Polostan. Over time, she evolves from a fervent believer to a quietly disillusioned survivor, a tragic figure straddling two collapsing worlds.

Bob “The Engineer”

An American steel engineer who mentors Aurora and serves as her early contact into the Soviet industrial efforts. Bob, originally filled with leftist sympathies, is drawn to the idea of building a better world through technology and rational planning. However, witnessing both American capitalism’s failures and Soviet brutality leads him into deep cynicism. His journey parallels Aurora’s, though his spirit is broken earlier, and he becomes emblematic of the technocrat caught between ideology and survival.

Comrade Fizmatov

A former university professor and expert metallurgist, Fizmatov has been sentenced to forced labor at Magnitogorsk as a political prisoner. His vast technical knowledge keeps him invaluable to Soviet authorities, but he is under constant threat of denunciation. Wise, sardonic, and philosophical, Fizmatov acts as a surrogate father figure to Aurora in Magnitogorsk, offering her hard-earned truths about survival under Stalin’s regime.

Comrade Tishenko

A young, aggressive Party agitator obsessed with rooting out sabotage and enforcing ideological purity. Tishenko embodies the paranoia and opportunism of Stalinist bureaucracy, willing to denounce friends and comrades alike to advance his career. His antagonistic relationship with Fizmatov and quiet suspicion toward Aurora represent the ever-present threat of ideological betrayal.

Shaimat

A Tatar worker and fellow member of Aurora’s Shock Brigade. Practical, humorous, and loyal, Shaimat becomes one of Aurora’s few genuine friends in Magnitogorsk. His rural background and limited education contrast sharply with the ideological sophistication around him, highlighting the diversity — and fragility — of the Soviet working class.

Veronika

Aurora’s protector during her early childhood in Petrograd, Veronika is a veteran of the Red Women’s Death Battalion. Hardened by war, she imparts crucial survival lessons to young Aurora, including the necessity of vigilance in a predatory world. Though a relatively minor character, Veronika leaves a lasting emotional imprint on Aurora’s worldview.

Maxim Alexandrovich Artemyev

Aurora’s father, a committed American communist who emigrated to the Soviet Union to help build the Revolution. Stern, idealistic, and often emotionally distant, Maxim represents the utopian dreams that so often curdle into authoritarianism. His abandonment of Aurora’s mother and rigid adherence to ideology foreshadow the disillusionments Aurora herself will face.

Aurora’s Mother (“Mama”)

An unnamed woman from Montana who initially supports her husband’s communist ideals but becomes deeply disillusioned with Soviet life. Eventually returning to America, she symbolizes the pull of personal freedom and human warmth that Soviet ideology fails to replicate. Her departure leaves a psychological wound in Aurora that never fully heals.

A Novel in Three Movements

The novel’s structure can be loosely divided into three parts:

- The Departure (1933–34) – Aurora’s transformation from “Dawn” to “Aurora,” and her decision to return to the Soviet Union to help build socialism.

- The Ascent (1934–35) – Life in Magnitogorsk: a brutal but hopeful period in which engineering meets ideology, and where human dignity is bartered daily against quotas and survival.

- The Reckoning (1936 onward) – The disillusionment that sets in as the purges begin, as her comrades disappear, and as Aurora comes to terms with the failure of both Western democracy and Soviet utopia.

Blending Fiction with History

Stephenson’s Polostan blurs the line between fiction and history with remarkable finesse. Real events—such as the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, the rise of Magnitogorsk, and the cultural purge of the late Stalinist era—are recast in the novel with granular detail and dramatic poignancy. Aurora’s interactions with historical stand-ins—reminiscent of Stalinist bureaucrats and American New Deal reformers—feel both surreal and authentic.

The world of Polostan is always on the brink of collapse. Even during moments of triumph—like when Blast Furnace #4 finally roars to life—Stephenson tempers the celebration:

“It would have been funny had she not been here”.

This line, buried in a vivid depiction of frostbitten laborers assembling industrial scaffolding, underscores the bitter irony that runs throughout the book.

Themes in Polostan

Idealism vs. Reality

At its core, Polostan is a meditation on the collision between idealism and brutal reality. Aurora begins the novel filled with hope that socialism — purified from capitalism’s inequalities — can create a new, better world. Her journey to Magnitogorsk and later Polostan, however, exposes the vast chasm between revolutionary ideals and the grinding cruelty of real-world implementation. Neal Stephenson shows how even the noblest visions are vulnerable to corruption, incompetence, and human frailty. In both America and the Soviet Union, dreams of a better society are co-opted by systems that ultimately prioritize power over people.

The Human Cost of Utopia

One of the novel’s most pervasive and haunting themes is the cost exacted by the pursuit of utopia. In Magnitogorsk, workers labor and die in appalling conditions to meet impossible quotas. In Polostan, surveillance and betrayal replace community and trust. Stephenson illustrates that every attempt to create a perfect society, whether capitalist or communist, carries an inherent willingness to sacrifice individuals for the “greater good.” Aurora’s personal losses — of friends, innocence, and faith — mirror the larger collective disillusionment that engulfs both her worlds.

Technology as Double-Edged Sword

Throughout Polostan, technology is depicted as both miraculous and monstrous. Bob, the engineer, initially believes that rational design and engineering feats like the Golden Gate Bridge and Magnitogorsk’s furnaces can uplift humanity. Yet Stephenson makes it clear that technology, without ethical grounding, becomes another tool of oppression. The very steel and concrete that symbolize progress also construct prisons — physical and ideological. Industrial might, while impressive, ultimately serves systems indifferent to the human beings trapped within them.

East vs. West: Twin Failures

Rather than framing the Cold War narrative of Soviet communism versus American capitalism as a binary struggle between good and evil, Stephenson presents them as mirrored failures. In Depression-era America, Bob witnesses violent labor crackdowns, widespread unemployment, and the callous indifference of capitalist elites. In the Soviet Union, Aurora confronts starvation, secret police terror, and betrayal. Both societies betray their founding promises, suggesting that human greed, fear, and ambition can warp any system, regardless of its theoretical virtues.

Surveillance, Betrayal, and Paranoia

In Magnitogorsk and Polostan, distrust becomes a way of life. Informants lurk everywhere. One careless word can mean arrest or death. Aurora and her companions constantly navigate an atmosphere where ideological purity is demanded but practically impossible. Tishenko’s obsession with uncovering “wreckers” exemplifies the self-consuming nature of Stalinist paranoia. Stephenson portrays surveillance not only as a political tool but as a corrosive force that dissolves human relationships, turning communities into isolated, fearful individuals.

Identity, Exile, and Belonging

Aurora’s shifting names — from Dawn to Avrora to Aurora — reflect her broader struggle with identity. Raised between two worlds, she belongs fully to neither. In America, she is too Russian; in the Soviet Union, she is too American. By the novel’s end, Aurora is effectively stateless, emotionally and ideologically. Stephenson uses her character to explore the alienation of those caught between ideologies, cultures, and histories — suggesting that true belonging may be impossible when grand systems demand loyalty at the expense of personal truth.

The Fragility of Truth and Memory

Polostan also interrogates how history is remembered and rewritten. Aurora’s early childhood memories of Petrograd are filled with shifting narratives: marriage dissolves with the removal of a ring; street performances reenact fabricated histories. Truth, in Stephenson’s novel, is malleable — shaped by whoever controls the means of communication, whether through propaganda in Petrograd’s schools or agitators’ speeches in Magnitogorsk. By the time Aurora reaches Polostan, she understands that memory itself is a battleground, and survival often requires forgetting or distorting the past.

Though set in the 1930s, Polostan by Neal Stephenson is searingly relevant in our current era of ideological extremism and collapsing institutions. The specter of authoritarianism is alive and well, as is the temptation to outsource personal agency to some larger cause.

One of the novel’s most devastating themes is the commodification of human beings in the name of progress. Whether it’s Soviet planners treating people as “units of productivity” or American bosses seeing workers as cogs, Stephenson shows that no ideology is immune to dehumanization. Aurora, watching a fellow worker freeze to death on a steel girder, thinks not of policy, but of poetry:

“Probably the closest thing to Christmas bells that would reach Aurora’s ears in 1933”.

This juxtaposition of horror and beauty is the beating heart of Polostan. Every political system it depicts is simultaneously awe-inspiring and grotesque, noble and absurd.

Stephenson also weaves in urgent feminist and queer undertones. Aurora—constantly underestimated, surveilled, and objectified—becomes a kind of ideological flâneur. She sees through the cracks in systems that were never designed for her to thrive in. Bob, navigating queer invisibility, finds momentary sanctuary in structure—but never love. Their interactions offer some of the novel’s most humanizing passages.

“There were only so many circumstances in which a thirty-year-old bachelor engineer could be seen conversing with a girl who was still young enough to attend high school”.

The subtle acknowledgement of societal judgment is what makes Polostan so layered.

10 Highlights

1. The Golden Gate Bridge Project: Stephenson brings to life the details of early 1930s San Francisco, capturing the engineering challenges and symbolism behind building a bridge as iconic as the Golden Gate.

2. Aurora’s Character Arc: Aurora’s transition from Dawn to Aurora, from a naive farm girl to a politically savvy survivor, is one of the novel’s most engaging elements. Her evolution symbolizes the personal transformations taking place during this tumultuous time.

3. The Use of Historical Figures: The novel integrates real-life figures from the era, such as Stalin and American industrialists, to give the story a historical weight, while keeping the narrative fictional.

4. Magnitogorsk’s Industrial Scene: Stephenson paints a vivid picture of Magnitogorsk, the Soviet Union’s steel heart, exploring the immense human cost and industrial achievements of Stalin’s five-year plans.

5. Tensions Between Capitalism and Communism: One of the novel’s main thematic focuses is the ideological clash between the capitalist West and the communist East, as represented by the characters’ experiences and internal conflicts.

6. The Engineering Feats: Throughout the novel, engineering and technical prowess are symbols of power, from the Golden Gate Bridge to the Soviet steel mills, illustrating how innovation and progress come at both personal and societal costs.

7. The Dynamic Between Bob and Aurora: Their evolving relationship serves as a mirror to the larger ideological shifts of the time, as they oscillate between personal desires and political realities.

8. The Plight of the Workers: Both in America and the Soviet Union, the novel does an excellent job portraying the conditions of workers—whether they are riveters in San Francisco or forced laborers in Soviet Russia.

9. Aurora’s Quest for Freedom: Aurora’s relentless pursuit of self-determination in a world that tries to pigeonhole her—be it as a Soviet agent, a worker, or a woman—is an inspiring narrative thread.

10. Bob’s Moral Quandary: The protagonist’s struggle with his role in a system that produces both great advancements and enormous suffering provides a deep reflection on personal ethics and responsibility in times of rapid change.

5 most important takeaway lessons from Polostan by Neal Stephenson:

1. The Human Cost of Progress

One of the central lessons from Polostan is the immense human cost behind large-scale industrial progress. Whether in the Soviet Union’s steel mills or the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge in the United States, the novel highlights how technological advancements and industrial growth come at the expense of the workers who drive them.

The story illustrates the physical toll on laborers, as well as the moral and emotional consequences faced by those who orchestrate and manage these projects. Progress often demands sacrifices, and the novel doesn’t shy away from showing the suffering involved.

2. The Complexity of Ideological Conflict

The novel deeply explores the conflict between capitalism and communism, showing that the lines between these ideologies are not always clear-cut.

Through the experiences of Bob and Aurora, we see that neither system is perfect, as both produce suffering and inequality. Stephenson invites readers to question the extremes of both ideologies, illustrating how people in both systems struggle to balance personal values with societal pressures.

The novel suggests that while ideologies may offer solutions, they also create new forms of oppression and control.

3. The Importance of Adaptability

Aurora’s character arc is a powerful lesson in adaptability. She begins as a naive farm girl, becomes Dawn, and finally emerges as Aurora—a strong, determined individual navigating a world of political and personal upheaval.

Her journey demonstrates that survival in turbulent times requires resilience, the ability to shed past identities, and a willingness to change.

Aurora’s ability to navigate different roles—spy, worker, and woman—underscores the importance of staying flexible in the face of overwhelming challenges.

4. Moral Ambiguity in Leadership

Bob’s internal conflict as an engineer working in both capitalist America and communist Russia reveals the moral ambiguity faced by leaders.

He is torn between his professional duty to build and create and the ethical implications of his work. Whether building bridges in San Francisco or steel mills in Magnitogorsk, Bob realizes that leadership often involves difficult decisions that have far-reaching consequences for the people involved.

The novel shows that moral clarity is rare in leadership positions, especially when those decisions affect human lives.

5. The Power of Individual Agency

Despite being caught in the gears of larger historical and ideological movements, Polostan emphasizes the importance of individual agency. Both Bob and Aurora make choices throughout the novel that shape their lives and the lives of those around them.

Aurora’s determination to forge her own path, even in the restrictive environment of the Soviet Union, highlights the power of personal will. The novel suggests that while larger forces may be at play, individual actions and decisions still hold significant weight in shaping one’s destiny.

These lessons provide a deeper understanding of how individuals navigate complex systems of power, progress, and ideology, making Polostan a thought-provoking reflection on history and human nature.

Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content: Ideology Versus Identity

Polostan by Neal Stephenson is, at its core, a collision of ideologies—an ideological Grand Slam where the bats are made of steel and the balls are soaked in blood. The novel does not merely represent the clash between capitalism and communism; it lays bare the fragility of belief systems when confronted with the needs of the individual human soul.

Stephenson supports his arguments not through polemic, but through lived experience—Aurora’s, Bob’s, even secondary characters like Comrade Fizmatov or Tishenko. Consider this reflection when Aurora watches priests, forced into penal labor, dig out turbines buried by bureaucratic incompetence:

“Miracles no longer belonged in the Soviet Union, so ice and gravity were doing their best to tear it all down”.

That single line doesn’t just criticize Soviet inefficiency—it eulogizes lost faith in human possibility. Polostan by Neal Stephenson doesn’t take sides; it dismantles every side. It suggests that belief is only as strong as the scaffold supporting it—and that scaffold is cracking.

Furthermore, Stephenson doesn’t fall into the trap of romanticizing the West as an ideological safe haven. Through Bob’s eyes, we see America as an exclusionary machine that rewards order and punishes divergence—especially sexual, racial, and gender-based.

“As much as he hated the country and the people who ran it, his engineer’s heart thrilled to see it”.

Bob loves what America builds, but not what it believes. In this, Polostan functions as a literary Möbius strip, looping back upon itself in a way that makes both communism and capitalism feel like reflections of each other.

Style and Accessibility: A War of Words and Warmth

Stylistically, Polostan by Neal Stephenson is more lyrical and emotionally charged than many of his earlier techno-heavy novels. While he still indulges in his signature deep dives into engineering (the riveting logistics of building a blast furnace, for instance, or the nuances of railcar design), the prose is leavened by Aurora’s emotive voice and internal conflict.

Her dual consciousness—Dawn and Aurora—creates a narrative rhythm that feels almost operatic. A key moment comes when she reflects:

“She knew from maps that the Ural Mountains were off to the west… This—the fact that they were east of the Urals—meant they were technically in Siberia”.

The irony here is both geopolitical and psychological. Just as she’s displaced in location, so too is she dislocated in identity. Her language, thoughts, and values are torn between continents—and Stephenson’s prose captures this fragmentation without ever losing clarity.

The book is dense, no doubt, but it’s accessible. Even when readers don’t grasp every historical nuance, they will feel the emotional and philosophical weight of Aurora’s journey. It’s Stephenson’s most personal novel to date, written with genuine heartbreak and subdued fury.

Author’s Authority: Neal Stephenson, The Cartographer of Systems

Stephenson’s authority in Polostan is undeniable. His grasp of Soviet history, engineering principles, and the emotional topography of revolution is masterful. But what elevates this work is his ability to humanize abstract systems.

Whereas Cryptonomicon reveled in cryptography and Anathem in metaphysics, Polostan finds transcendence in the tactile: steel under frostbitten fingers, the crunch of snow beneath soldiers’ boots, a shared cigarette amid propaganda.

Stephenson has clearly done his research. From the real-world Magnitogorsk project to the nuances of Soviet propaganda campaigns and industrial sabotage accusations, the detail is exhaustive—but never exhausting. Every blueprint is grounded in blood.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths: A Monument of Narrative and Ideological Ingenuity

1. Masterful World-Building

One of the most remarkable aspects of Polostan by Neal Stephenson is its immersive world-building. Stephenson doesn’t just describe settings—he reconstructs them with such fidelity that the reader feels transported to 1930s Magnitogorsk, trudging through the snow with Aurora and her comrades.

Consider the vivid atmosphere in this passage:

“The Industrial Lake… had been for months. Thick enough to host a sparse suburb of ice-fishing shacks”.

Stephenson paints the Soviet industrial dream not as propaganda, but as cold steel and blistered hands. His depiction of Soviet infrastructure projects rivals the realism of Tolstoy’s battlefields or Hugo’s Parisian sewers. It’s not just setting; it’s sociology.

2. Multifaceted Protagonist

Aurora is perhaps Stephenson’s most fully realized character to date. Her duality—Dawn/Aurora, American/Russian, child/soldier—makes her an evolving lens through which we interrogate the world.

From childlike memory:

“She must have been aware of things before… But the first time she was aware of being aware…”,

to ideological disillusionment, Aurora anchors the reader. Her resilience and intelligence elevate her beyond trope or token—she is the moral conscience of the novel.

3. Brilliant Integration of History and Fiction

Few contemporary authors can fuse real events and fiction with such dexterity. Stephenson makes no apologies for blurring truth with imagination. Real cities, real policies, and real ideological programs form the bedrock of Polostan, but they’re filtered through a speculative, almost dreamlike quality.

Take the fictional portrayal of the Storming of the Winter Palace:

“All of the good hiding places became known; the Whites couldn’t win”.

This blending of childish games with historical reenactment demonstrates the novel’s core irony—politics is play, but with devastating consequences.

4. Poetic Prose and Emotional Depth

Stephenson’s language in Polostan is leaner and more lyrical than usual. He captures emotional nuances without losing intellectual weight. Even minor characters, like Fizmatov (a penal laborer with a PhD), are rendered with tragic dignity.

“He’d already been sentenced to death. This had been commuted to ten years at Magnitogorsk.”

There’s something breathtaking about how Stephenson delivers fatalism with such plain beauty.

5. Philosophical and Political Sophistication

Stephenson doesn’t push an agenda—he invites inquiry. He critiques both communism and capitalism, but he does so with nuance. In today’s world of black-and-white narratives, Polostan by Neal Stephenson stands out for its intellectual honesty.

Weaknesses: Not for the Faint of Heart or Short of Time

1. Dense and Demanding

Despite its emotional richness, Polostan remains a challenge to read. At over 700 pages and layered with historical references, it demands time, attention, and historical knowledge. Some readers may find themselves Googling obscure Soviet organizations, or struggling to keep pace with ideological debates.

This is not accidental. Stephenson assumes his reader has the patience—and intellect—to follow him. But in doing so, he risks alienating those unfamiliar with Soviet or American industrial history.

2. Limited Emotional Payoff for Side Characters

While Aurora and Bob are fully realized, some side characters feel more allegorical than alive. Tishenko, for instance, represents bureaucratic zealotry, but lacks emotional arcs. Shaimat, the likable Tatar, provides comic relief and insight, but eventually fades from the narrative.

This might be intentional—a reflection of Stalinist erasure—but it can leave the reader yearning for closure.

3. Pacing Issues in the Final Third

As the story transitions into the Purge era, the pacing tightens and becomes more paranoid—but also more disjointed. The sense of thematic compression might leave some readers confused. Major shifts in tone—particularly the leap from Magnitogorsk’s hard realism to Bob’s final internal monologues—may feel abrupt.

Stephenson is known for sprawling conclusions (see The Baroque Cycle), and here he reins himself in. But in doing so, the final chapters feel slightly rushed compared to the patient buildup earlier.

4. Not Easily Adaptable

This may not be a “weakness” in a literary sense, but Polostan is a novel that resists adaptation. Its strength lies in interiority and structure—qualities hard to replicate on screen. As a result, it may never reach mainstream recognition despite its brilliance.

Who Should Read Polostan?

If you’re a reader who craves narrative density, intellectual inquiry, and emotional authenticity, Polostan by Neal Stephenson will reward you profoundly. Scholars of Soviet history will find Stephenson’s accuracy and critique exhilarating. Fans of The Man in the High Castle, Doctor Zhivago, or The Spy Who Came in from the Cold will find echoes and expansions here. But even readers unfamiliar with this era will find resonance in Aurora’s quiet battle for agency and Bob’s delicate pursuit of dignity.

That said, this is not light reading. It is demanding. It is cold. But it is also full of warmth, beauty, and defiance. As such, Polostan is essential reading for anyone trying to understand how individuals persist in the face of systems that would erase them.

Standout Quotes

- “What if you could work on something bigger… and build socialism while you’re at it?”

- “You let him take you. You just let a strange man grab you and take you away… Never do it again”.

- “That’s what engineers do!” Bob said, but his voice trembled with something Aurora recognized: longing.

- “In every backward department there is a wrecker” — Tishenko’s voice was not ironic, but terrifyingly sincere.

In an age where books are often reduced to data points—ratings, reviews, adaptations—Polostan by Neal Stephenson reminds us that literature can still be a form of resistance. It resists simplicity. It resists being used. And it insists that history is not just something that happens—it’s something we survive.

Conclusion

Neal Stephenson’s Polostan is not just a historical novel, a political allegory, or a character study—it’s all of these things and more. It’s a literary odyssey forged in fire and ice, where human resilience is tested against the grinding gears of ideology. It forces readers to grapple with a central question that haunts both past and present: Can you build a world that honors human dignity if you treat people like raw material?

Stephenson doesn’t offer easy answers. Instead, he immerses us in the impossible tension between structure and soul. Through the eyes of Aurora—child, translator, soldier, believer—we see systems rise and fall, but the hunger for identity, meaning, and love persists. Polostan by Neal Stephenson is about what happens when your beliefs no longer protect you. And about what remains when your nation, your father, your God, your ideology has failed.

One of the most striking takeaways comes late in the novel, when Aurora, surrounded by fire, steel, and silence, reflects:

“She looked tired, stretched out, older than she was. But the eggs and hash she ordered would help her fill out that dress if she kept at it”.

This isn’t just a portrait of physical exhaustion—it’s an emblem of survival. Of rebuilding one’s self not from ideology, but from coffee, pie, and a sliver of hope.

Neal Stephenson has written a novel that feels less like a story and more like a blueprint of consciousness. It’s a meditation on failure—of systems, of parents, of memory—but also a celebration of what endures: language, effort, music, hands, frost, and dreams.

By the end, Aurora is no longer just a character; she’s a testament. A survivor’s whisper to the future: I was here. I mattered. I built something, even if it broke me.