What makes a corporate raider and a Hollywood Boulevard sex worker the beating heart of a modern fairy tale? Pretty Woman 1990 answers with disarming clarity: chemistry, wit, and a makeover—not of clothes, but of conscience.

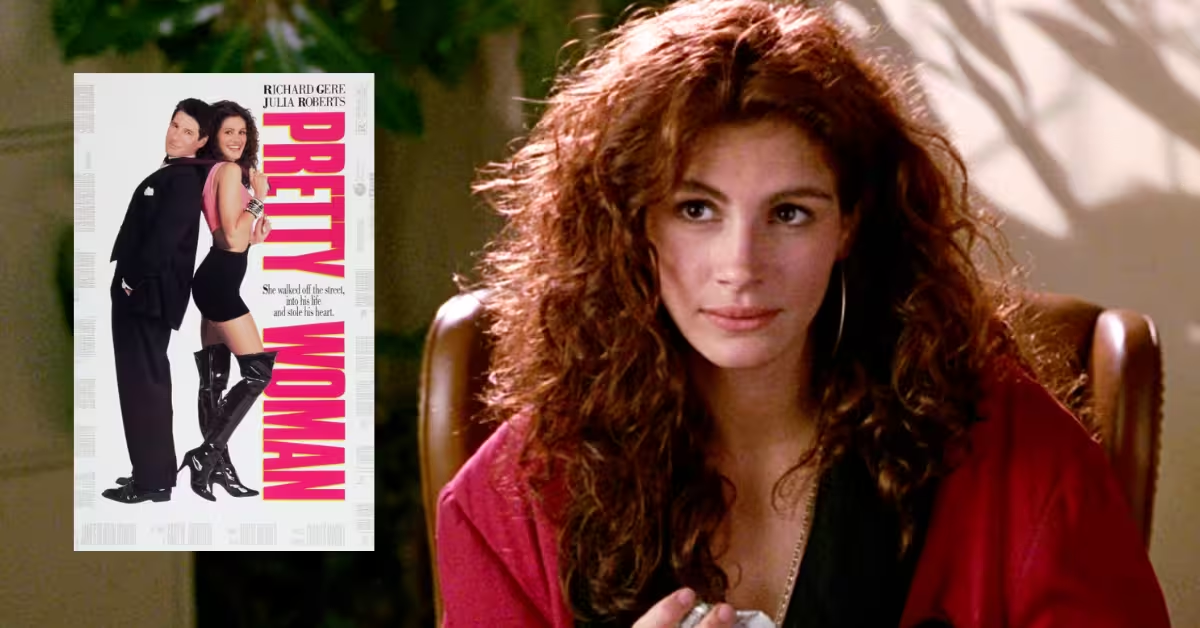

Directed by Garry Marshall and released on March 23, 1990, this romantic comedy stars Julia Roberts and Richard Gere in a story that dances between fantasy and class critique, set against the gleam of Beverly Hills. It became a phenomenon, grossing $463.4 million worldwide on a modest $14 million budget and propelling Roberts to globe-straddling stardom.

My overall impression? Pretty Woman 1990 is a glossy contradiction I find strangely irresistible: an R-rated Cinderella that knows it’s a fantasy and still convinces me to care. It remains one of the most discussed romantic comedies precisely because its fairy-tale ending coexists with darker, once-grittier DNA from an early draft titled 3000.

Beyond the Fairytale: The Complex Legacy of Pretty Woman

On the surface, Pretty Woman (1990) is one of cinema’s most beloved modern fairytales. The story of a vivacious Hollywood prostitute, Vivian Ward (Julia Roberts), who is hired by a ruthless but charming businessman, Edward Lewis (Richard Gere), for a week, only for them to fall in love, has enchanted audiences for decades. It’s a film celebrated for its unforgettable romantic quotes and jaw-dropping, timeless outfits that cemented Julia Roberts as a global superstar and fashion icon.

However, beneath this glossy romance lies a far more complex and controversial story. To truly understand “Pretty Woman” is to look beyond the romance and confront the dark secrets and mind-blowing details of its creation. The film we know today is a drastic departure from its original concept. Initially titled “3,000” (the amount Vivian was paid for the week), the script was a gritty, cautionary tale about class and addiction in Los Angeles.

This darker vision included a surprising and heartbreaking alternate ending that stands in stark contrast to the iconic fire escape finale. The shocking truth behind the original fairytale ending is that there wasn’t one; Edward was meant to shove a screaming Vivian out of his car and throw the money at her before driving away, leaving her in a dirty alley to fend for herself.

This initial script was so bleak that it was the astonishing reason Julia Roberts almost rejected her iconic role. It was only after the project was sold to Disney and director Garry Marshall came on board to transform it into a romantic comedy that she agreed to stay. These magical and unseen behind-the-scenes moments, including improvised scenes like Richard Gere snapping the necklace box on Roberts’ fingers, are what infused the film with its signature charm.

Despite its commercial success, the film has faced a powerful feminist critique that can’t be ignored. Critics and scholars continue to debate whether the film glamorizes sex work and presents a problematic narrative where a woman’s rescue and validation come from a wealthy man.

These discussions reveal that the legacy of “Pretty Woman” is not just about romance, but also about the complex and often controversial ways women’s stories are told. These ten facts—from its dark origins and alternate ending to the critical debates it still inspires—will forever change how you see the film, guaranteeing that a rewatch will be a completely new experience.

Full Plot Summary of Pretty Woman (1990)

Pretty Woman 1990 begins not with a meet-cute in a bookstore but with a stalled Lotus Esprit and a man who can buy and break companies yet cannot work a stick shift.

Opening Encounter

The story of Pretty Woman (1990) begins in the shimmering yet shadowy world of Los Angeles. Edward Lewis (Richard Gere) is a powerful and wealthy corporate raider visiting from New York. After leaving a glamorous business party in the Hollywood Hills, he borrows his lawyer Philip Stuckey’s Lotus Esprit sports car.

The problem? Edward cannot drive a manual transmission. Lost and struggling in the neon-lit streets, he drifts into Hollywood Boulevard — an area known for its red-light district (a section of a city with a high concentration of sex-oriented businesses, such as sex shops, adult theaters, and strip clubs, and where prostitution may be legal or illegal). It is there that he encounters Vivian Ward (Julia Roberts), a spirited streetwalker trying to earn her night’s living.

Vivian, sharp and practical, offers to help Edward drive the car to his luxury destination — the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. Though their first interaction is strictly transactional, an immediate spark of curiosity and tension flows between them.

Edward impulsively invites her up to his penthouse for the night. What begins as a business arrangement slowly turns into an unexpected connection. Despite some initial awkwardness, they sleep together, and Edward finds her company oddly refreshing, unlike the scripted and calculating conversations he is used to in his corporate life.

The Deal: A Week-Long Arrangement

The following morning, Edward realizes he must attend a series of important social and business events as he attempts to acquire Morse Industries, a struggling shipbuilding company run by elderly owner James Morse (Ralph Bellamy) and his grandson David.

For these appearances, he needs a presentable companion. Rather than dealing with the complexities of formal relationships, Edward proposes a simple deal: Vivian will stay with him for an entire week, accompanying him to dinners, meetings, and social events. In exchange, he will pay her $3,000.

Vivian agrees to the arrangement, though not without negotiating her worth. Edward also gives her money to buy suitable clothes. This moment begins the film’s most famous transformation arc — not just in terms of wardrobe, but in how Vivian learns to navigate a world of wealth and high society.

The Rodeo Drive Incident

Vivian ventures out to Rodeo Drive, the most exclusive shopping street in Beverly Hills, in search of a proper wardrobe. Dressed in her working attire, she is instantly judged by shop assistants, who dismiss her with disdain and refuse to serve her. Humiliated and furious, Vivian leaves the store in tears.

Back at the hotel, the kind-hearted manager Barney Thompson (Héctor Elizondo) notices her distress. Rather than scolding her, he treats her with dignity and respect, arranging for a friendly saleswoman to assist her. He even personally coaches her on dining etiquette so she can confidently accompany Edward to an important dinner. With his help, Vivian steps into a world that had previously ridiculed her, emerging transformed in a sophisticated cocktail dress. When Edward sees her that evening, he is taken aback by her elegance.

This transformation — though external in appearance — symbolizes the deeper respect and humanity Vivian deserves but has long been denied by society.

Dinner with the Morses

Edward takes Vivian to dinner with James Morse and his grandson David. The meal is awkward from the start, as the Morses express their displeasure with Edward’s ruthless plan: he intends to dismantle their family-owned company and sell its assets for profit. Vivian watches this exchange quietly but attentively. She begins to see Edward’s world not merely as an abstract game of deals and numbers but as one where real people’s lives and legacies are at stake.

Later, Edward confides in Vivian about his complicated relationship with his late father and how his business choices are shaped by unresolved resentment. For the first time, Vivian glimpses vulnerability beneath his polished exterior.

Polo Match and Betrayal

Edward takes Vivian to a polo match — an event designed to network with wealthy business contacts. Vivian mingles with David Morse, chatting innocently, but this arouses suspicion from Philip Stuckey (Jason Alexander), Edward’s cutthroat lawyer. Believing Vivian to be a corporate spy, Philip presses Edward for an explanation. Edward, in a moment of thoughtless pride, reveals the truth about Vivian’s background as a prostitute.

This careless disclosure humiliates Vivian and exposes her to cruelty. Philip later corners her alone and crudely propositions her, assuming her services are negotiable. Devastated and enraged, Vivian confronts Edward, furious that he betrayed her trust. Though Edward apologizes, admitting he acted out of jealousy when he saw her talking to David, the damage is done. This incident marks a turning point: Vivian begins to question not only Edward’s integrity but also whether this arrangement has deeper meaning or is destined to remain a financial transaction.

The Opera: Breaking the Rules of Intimacy

Seeking to mend their fractured connection, Edward surprises Vivian by taking her on a private jet to San Francisco to see La Traviata, an opera about a courtesan who falls in love with a wealthy man. The choice is deliberate — a mirror of their own situation.

Vivian is deeply moved by the performance, overwhelmed with emotion. That night, she breaks her personal rule: no kissing on the lips. For her, kissing is too intimate, reserved for real love, not business. By kissing Edward, she signals that their relationship has shifted beyond contract. Later, as Edward sleeps, Vivian whispers that she loves him, though he never hears it.

As their week draws to a close, Edward proposes a future arrangement: he will set Vivian up in a luxurious condominium, provide her with an allowance, and visit her occasionally. On the surface, this seems generous. But Vivian rejects the offer, realizing that it reduces her to a kept woman, not a partner.

She confides her childhood fantasy: being rescued by a knight on a white horse. The symbolism is clear — she desires love, respect, and equality, not transactional comfort. Though Edward is hurt by her refusal, her words challenge him to reconsider the way he conducts both his personal and professional life.

The Breaking Point

Edward meets with James Morse again, and instead of dismantling the company as planned, he chooses to work with him to preserve it. This moral shift infuriates Philip, whose financial interests are jeopardized by Edward’s newfound conscience.

Enraged, Philip storms to the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. Finding Vivian alone, he lashes out, blaming her for Edward’s softened resolve. In a shocking scene, he strikes her and attempts to assault her. Edward arrives just in time, pulls Philip away, punches him, and fires him on the spot.

The brutality of the encounter shatters the glossy façade of their arrangement and reminds Vivian of the dangers she faces simply by existing in vulnerable spaces. Yet it also demonstrates Edward’s transformation — he is no longer the detached corporate raider, but a man willing to stand up for someone he cares about.

Parting Ways

Afterward, Edward asks Vivian to stay with him one more night, not as an escort but because he wants her to. Vivian, however, declines. She recognizes that her future cannot depend on being someone’s accessory. Instead, she decides to leave Los Angeles, pursue a high school diploma, and move to San Francisco to begin a new life.

Before departing, she gives money to her roommate Kit De Luca (Laura San Giacomo), encouraging her to seek a different path. Inspired, Kit enrolls in beauty school, signaling the possibility of a fresh start for both women.

As Vivian waits at her apartment for the bus, ready to leave, Edward realizes what he truly wants. In a grand romantic gesture, he has his chauffeur drive him to her building. Standing tall through the sunroof of a white limousine, clutching a bouquet of flowers, Edward climbs the fire escape to reach her window — embodying the very knight on a white horse Vivian once dreamed of.

When he asks, “What happens after the knight rescues the princess?” Vivian replies, “She rescues him right back.” The two embrace and kiss passionately. The film closes on this reciprocal promise of love: not one-sided salvation, but mutual transformation.

What begins as a cynical business arrangement blossoms into an exploration of vulnerability, dignity, and respect. Beneath its glamour, Pretty Woman crafts a modern fairy tale where both protagonists rescue each other, not from poverty or loneliness, but from their own emotional limitations.

Commercially, Pretty Woman 1990 became a juggernaut: highest estimated domestic ticket sales for a rom-com (42,176,400 tickets) and $463.4M worldwide; at release it ranked among the top five global grossers of all time and held Disney’s highest-grossing R-rated record until 2024.

That’s not just box office trivia; it’s evidence that audiences recognized themselves in a fantasy and decided that, sometimes, fantasy tells the emotional truth better than realism.

Analysis

1. Direction and Cinematography

Garry Marshall directs Pretty Woman 1990 like a consciously modern fairy tale: the camera keeps Beverly Hills glossy, the hotel lobby ceremonious, the clothing boutiques theatrical, and the opera sequence reverent.

Charles Minsky’s cinematography prefers clean, flattering lighting and medium shots that preserve performance beats—especially in the Rodeo Drive humiliation/return-in-triumph passages, the polo-field suspicion, and the closing fire-escape tableau. The result is a look that reinforces the film’s wish-fulfillment arc without denying its class tensions. Even the famous improvised necklace-box snap—Roberts’ surprised laugh is real—feels emblematic of Marshall’s approach: cultivate spontaneity inside a careful frame so the fantasy feels alive.

What also stands out is Marshall’s tonal pivot away from the original, darker script 3000 toward an unabashed romance. That pivot—reportedly encouraged at the studio level—repositions the camera’s empathy squarely on the pair’s mutual humanization rather than the bleak economics of sex work in late-80s Los Angeles.

You still sense the shadow of that earlier script in key beats (the assault by Stuckey, the condo “arrangement” offer), but Marshall’s eye keeps returning to intimacy and kindness, often literalized by Barney’s quiet coaching and the opera’s emotional overture.

2. Acting Performances

If Pretty Woman 1990 became a cultural mainstay, it’s because its leads play transformation with delicacy. Julia Roberts doesn’t just sparkle; she calibrates Vivian’s rules, pride, and curiosity so that each setback and kindness lands with human weight.

Critics at the time predicted the role would make her a major star, and the film’s award record confirms it (including a Golden Globe win and Oscar/BAFTA nominations). Richard Gere underplays Edward—watchful, slightly withdrawn, gradually letting decency displace detachment—which is precisely why the late-film moral turn reads as earned rather than perfunctory.

Contemporary critics split on tone, but many singled out the performances and chemistry as the glue that holds the fantasy together.

Among the supporting cast, Héctor Elizondo’s Barney is a master-class in gracious authority; Laura San Giacomo’s Kit, both brittle and loyal, steals scenes without puncturing the film’s buoyancy; and Jason Alexander makes Stuckey’s entitlement viscerally unpleasant, which sharpens the film’s critique of power. (Alexander, notably, was just then becoming TV-famous as George Costanza.)

3. Script and Dialogue

J. F. Lawton’s screenplay—refashioned from 3000—is built on oppositions (money vs. meaning, transaction vs. tenderness) and resolves them through choices, not speeches. The best lines (“Big mistake. Big. Huge.”; “She rescues him right back.”) endure because they distill character agency and the movie’s thesis in a few syllables. The dialogue toggles between crisp banter and small, humane disclosures (Edward’s father, Vivian’s rules), helping Pretty Woman 1990 feel personable rather than merely posh.

Pacing-wise, the script plants clear tent-poles—polo, opera, Stuckey’s confrontation, the parting, the fire-escape reunion—so the week tracks like a classic five-beat romance. The rewriting history (from grim cautionary tale to romantic comedy) is visible in the seams, yet the final cut speaks in one voice.

4. Music and Sound Design

James Newton Howard’s score keeps Pretty Woman 1990 buoyant—warm strings, gentle motifs that never smother dialogue. The soundtrack became a phenomenon in its own right (triple-platinum RIAA), anchored by Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman,” Roxette’s “It Must Have Been Love” (a U.S. #1 in June 1990), and Go West’s “King of Wishful Thinking.”

That pop scaffolding frames Vivian’s metamorphosis with radio-friendly uplift. In sonic counterpoint, the La traviata sequence elevates the story’s emotional register and mirrors Vivian’s own breach of the no-kissing rule—a rare case where a needle-drop (opera, here) refracts character psychology rather than simply decorating it. (Fun bit: the hotel-lobby piano piece is Gere improvising.)

5. Themes and Messages

At its core, Pretty Woman 1990 argues for the dignity of choice. Vivian is never reduced to a makeover mannequin; she sets rules, takes the deal on her terms, rejects the condo, and chooses a different future.

Edward’s arc is about the cost of abstraction: business plans affect people; the film’s shipyard family makes that visible. Their transformations meet in the final image: rescue as reciprocity. That is why Pretty Woman 1990 still resonates across generations—it’s a romance about two adults renegotiating what power means, using kindness as leverage.

The film also invites (and has always received) debate: is this a “yuppie fantasy” that smooths over structural realities of sex work? Or a Pygmalion-style fable that uses glamour to stage moral growth?

The critical record shows both positions—mixed critic scores but an A from CinemaScore audiences—which is another way of saying the movie delivers emotional truth for many while provoking skepticism in others. Pretty Woman 1990 survives because it makes room for both readings.

Comparison

Lineage. The film openly echoes Pygmalion/My Fair Lady—manners lessons, couture, a social debut—yet flips the agency: Vivian isn’t “sculpted” into acceptance so much as she chooses a version of herself already present, now recognized. The script’s documented shift from the gritty 3000 to a fairy-tale form (pushed during development) places Pretty Woman 1990 near other late-80s/early-90s studio romances that balance cynicism with warmth.

Within Marshall’s work. Compared to Marshall’s Overboard (1987), which some critics found undergirded by “covetousness and underlying misogyny,” Pretty Woman 1990 feels softer, less farcical, more invested in consent and mutuality—even if not everyone buys the alchemy. That contemporary contrast appears in reviews that both ding and defend the film in the same breath.

Against contemporaries. Stack it beside Wall Street-era narratives and you see why Pretty Woman 1990 struck gold: where other films punish acquisitive men, this one offers redemption via attention to another person.

That emotional availability is what separates it from colder corporate dramas and why audiences embraced it so strongly. (Box-office dominance across multiple weeks and markets confirms that mass appeal.)

Audience Appeal / Reception & Awards

Critical split, audience embrace. Aggregators now show mixed critic scores—65% on Rotten Tomatoes, 51/100 on Metacritic—alongside an A CinemaScore from opening-night audiences.

That’s the classic crowd-pleaser pattern: some critics balked at the “hooker with a heart of gold” trope or the film’s glossy treatment of sex work; others (Ebert, Maslin) highlighted an unusually romantic tenor and the star-making force of Roberts’ performance. Pretty Woman 1990 is the rare studio romance that critics still argue about—and people still rewatch.

Awards snapshot

- Academy Awards: Best Actress nomination — Julia Roberts.

- Golden Globes: Best Actress (Comedy/Musical) — Julia Roberts (WIN); the film and Richard Gere also nominated.

- BAFTA: Nominations for Best Film, Best Actress (Roberts), Best Original Screenplay, Best Costume Design.

- AFI: #21 on 100 Years…100 Passions.

Who will love it today?

- Fans of character-driven romance who want the comfort of transformation arcs.

- Viewers who enjoy fashion, makeover, and opera-as-emotion sequences.

- Casual audiences and date-night viewers (the CinemaScore “A” says as much).

Box-office context.: Budget $14M; worldwide gross $463.4M. It logged 42,176,400 estimated U.S. tickets (Box Office Mojo’s top romantic comedy by tickets sold), became Disney’s top grosser at the time, and—until 2024—remained Disney’s highest-grossing R-rated release.

Few rom-coms have combined critical debate with such commercial thunder. That scale explains the long half-life of Pretty Woman 1990 in pop culture.

Personal Insight

When I revisit Pretty Woman 1990, I don’t watch it as a manual for love; I watch it as a parable about attention. The plot is pure fantasy, yes, but the behaviors are not. Vivian pays attention to how people treat service workers, to the cracks in Edward’s armor, to the difference between investment and extraction. Edward, once he finally looks rather than just sees, discovers that power without regard is a hollow exercise. The film’s gift is to make that recognition feel pleasurable rather than punitive.

I’ve also grown more sensitive to how Pretty Woman 1990 navigates class performance. Clothing matters here, not because silk absolves anyone, but because context changes how we are read. The Rodeo Drive scenes remain cathartic because they make a very simple point with operatic flourish: respect is not a luxury. It should never require a platinum card or a hotel manager’s blessing. Yet the movie also suggests that a little institutional kindness can open doors (Barney’s role is quiet heroism).

Consent and negotiation are surprisingly central. Vivian’s rules—especially the ban on kissing, the one boundary that finally melts—give the romance its shape. The week-long contract is the film’s way of saying: adults can negotiate, and those negotiations can evolve. That’s a healthier model for romance than many grittier dramas manage.

Finally, I think about redemption. Pretty Woman 1990 doesn’t redeem Edward because he can spend; it redeems him when he decides not to consume—when he saves a company rather than dismantling it, when he listens to Jim Morse as a person, not as expendable inventory.

That pivot may be fairy-tale neat, but the moral is practical: choose the version of yourself that leaves more whole things behind. If you strip away the silk and the skyline, that lesson remains sturdy.

Quotations

- “Big mistake. Big. Huge.” (Rodeo Drive return)

- “She rescues him right back.” (final fire-escape)

- “I want the fairy tale.”

- “I say who, I say when, I say how.”

- “Welcome to Hollywood! What’s your dream?”

- “I’m not a prostitute. I’m a safety girl.”

Pros and Cons

Pros

- Radiant lead chemistry (Roberts/Gere) that anchors the fantasy.

- A soundtrack/score that lifts emotion without syrup (RIAA triple-platinum; “It Must Have Been Love” hitting #1).

- Set-pieces that still sing: Rodeo Drive, opera, fire escape.

- Barney Thompson as exemplar of humane gatekeeping.

- A clean five-beat arc; excellent comedic timing (e.g., necklace-box snap).

Cons

- Gloss risks minimizing structural realities of sex work (a frequent critical charge).

- The “hooker with a heart of gold” trope can feel dated to some viewers.

- Some critics read the film as status-symbol obsessed despite its “love over money” stance.

Conclusion

Pretty Woman 1990 endures because it is shameless about two unfashionable ideas: people can change, and kindness counts.

You can interrogate its fantasy while still being moved by its attention to dignity and choice. Add the star-making radiance of Julia Roberts, Richard Gere’s understated turn, and a soundtrack that refuses to age, and you have a romance that keeps teaching by delighting.

Recommendation: a must-watch for romance fans and a rewarding rewatch for skeptics—the craft and performances are that sturdy. (And yes, the red dress is still unforgettable.)

Rating

4.5 / 5 — A modern fairy tale that earns its heartbeat.