If you have ever been told you are “too emotional,” “too intense,” or simply “too much,” Simply More: A Book for Anyone Who Has Been Told They’re Too Much by Cynthia Erivo is the rare book that refuses to shrink you, and instead shows you how to grow into your full size.

In Simply More, Cynthia Erivo turns her own story—running literal marathons, surviving family estrangement, navigating racism, homophobia and the pressure of global fame—into a guide for anyone who has learned to tone themselves down just to feel safe.

At heart, the best idea in the book can be put very simply: the sides of you that have been called “too much” are often the exact gifts you’re here to use, and the work of adulthood is learning how to honor them with boundaries, courage and care.

Erivo keeps returning to one line in her opening letter: we’re “called to keep expanding and growing and evolving,” a gentle insistence that becoming “simply more” of yourself is not arrogance but responsibility.

What makes that claim more than feel-good rhetoric is how closely it tracks with research on self-silencing and marginalisation: studies show that women who chronically suppress their needs to stay “acceptable” report significantly higher depression and anxiety scores, and LGBTQ+ people who hide their identity at work face higher stress and burnout, according to Ashti Emran, Naved Iqbal and Imtiyaz Ahmad Dar.

As a reading experience, Simply More is best for readers who like personal, story-driven wisdom and don’t mind a spiritual, reflective tone, and probably not for those who want a highly structured, step-by-step workbook with checklists and productivity hacks.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

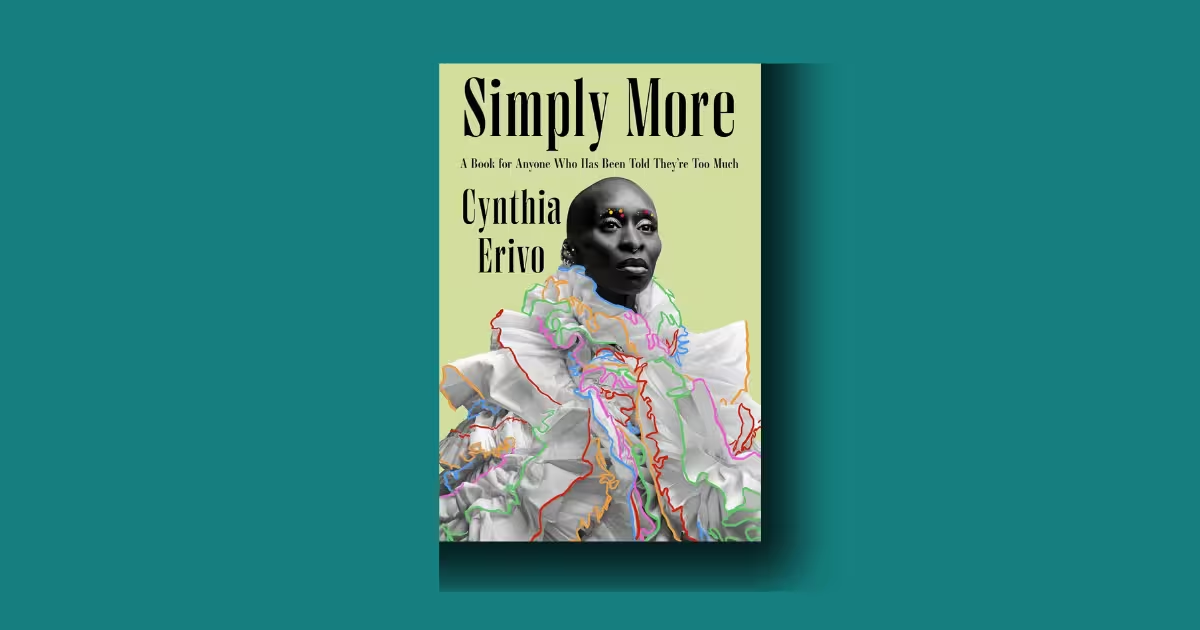

Simply More: A Book for Anyone Who Has Been Told They’re Too Much is Cynthia Erivo’s 208-page blend of memoir and life-lessons, published by Flatiron Books (US) on 18 November 2025 and by Macmillan in the UK on 20 November 2025, after an earlier announcement had tentatively listed 2026.

The book describes itself as a series of “powerful, personal vignettes” in which Erivo reflects on how she has grown as an actor and human and how we are all “capable of so much more than we think,” a description echoed almost verbatim across Macmillan, Pan Macmillan and bookseller catalogues.

Formally, Simply More sits between celebrity memoir, spiritual reflection and motivational manual: it is organised like a marathon, with three main parts—“Run the First Ten Miles with Your Head,” “Run the Second Ten Miles with Your Legs,” and “Let Your Heart Carry You the Rest of the Way”—each containing short chapters with titles that sound like advice to a friend (“You Can Run Marathons,” “Take the Nudge,” “Make a Pact,” “Do Not Let Rage Define You”).

Cynthia Erivo is, by now, a household name: a Grammy, Emmy and Tony winning performer, twice Oscar-nominated, who broke out in The Color Purple on Broadway and went on to star in Harriet, Genius: Aretha and, most prominently in recent years, as Elphaba in the two-part Wicked film adaptation.

She has also fronted BBC Proms concerts and major film soundtracks, and in 2025 released a personal studio album, I Forgive You, focusing on vulnerability and authenticity—another sign that this book is part of a wider project of her living “out loud” as an artist.

According to both her own “About the Author” page and recent interviews, Erivo writes as a Black British, queer, Nigerian-heritage woman who knows from the inside what it means to be scrutinised for being “too intense,” “too political” or “too queer,” and she explicitly frames Simply More as a book for anyone who has experienced that same policing.

That framing matters because the book’s central thesis is not neutral self-help; it argues that in a world where marginalised people are routinely told to be smaller, choosing to be “simply more” is both a survival skill and a quiet act of resistance.

Erivo’s stated purpose is to show, by example, how you move from self-doubt and over-performance for others into a steadier, embodied confidence that lets you run the marathons that matter to you—onstage, onscreen or in your own ordinary life.

2. Background

We are living in a time when vast numbers of people say they cannot be fully themselves at work or in their families, and the language of being “too much” has become strangely common.

In one analysis of performance reviews by the language-analysis firm Textio, 75% of women’s evaluations contained personality-based feedback (too abrasive, too emotional, not collaborative enough) compared with only 2% of men’s, and other research finds that high-performing women are far likelier than men to be told to adjust their tone or attitude instead of their skills.

Meanwhile, UK data suggest that around 39% of LGBTQ+ employees are not “out” at work and feel pressure to downplay parts of themselves, and self-silencing research going back to Dana Crowley Jack in the 1990s has linked chronic suppression of authentic feelings—especially in women—to higher rates of depression, anxiety and relationship distress.

Against that cultural backdrop, a book that unapologetically centres a Black, queer woman refusing to shrink herself for church, family or Hollywood feels less like a celebrity side project and more like a field guide for people who are tired of apologising for existing at full volume.

The timing is also symbolic: Simply More arrives in the same season as Wicked: For Good and follows Erivo’s GLAAD-honoured work for queer visibility, so the book reads like both a personal testimony and a companion piece to her public role as one of the most visible queer Black women in mainstream musical cinema.

3. Simply More Summary

The structure of Simply More is deceptively simple: Erivo uses the marathon as a long metaphor for a life fully lived, arguing that you run the first miles with your head (clarity, self-knowledge, courage to start), the next with your legs (daily discipline, craft, boundaries) and the last stretch with your heart (love, faith, community, meaning).

Each of the three parts contains short chapters that zoom in on one lesson or scene—learning to run 5Ks in New York, being scolded for asking questions in English class, watching her father walk away at sixteen in a Tube station, recording Wicked while in a harness for twelve hours, standing in the centre of a Jesus Christ Superstar controversy, or building an intentional, protective friendship with Ariana Grande on set—and every time, she circles back to the question, “How big a life are you willing to live?”.

Rather than a linear timeline, the book moves thematically: childhood passions, early teachers, the awkwardness of being “too curious,” the pain of being abandoned, the way ambition can become a hamster wheel, the tenderness of queer love and chosen family, the politics of being a Black woman playing Jesus and a green-skinned witch, and the quiet spiritual practice of saying “thank you” as a daily prayer.

The result is that you don’t just learn what happened to Cynthia Erivo; you watch her build a working philosophy of being “simply more” out of those events, and you are repeatedly invited to apply the same questions to your own life—what did you love as a child, who truly sees you, where are you still shrinking.

By the time you close the book, the marathon metaphor has become a map: where you are now is just one mile marker, and you are allowed to run at your own pace, in your own body, towards a finish line you choose.

Part One – Run the First Ten Miles with Your Head

Part One opens with running, not singing, which feels like a deliberate surprise from someone best known for the sheer power of her voice.

In “You Can Run Marathons,” she begins with a confession of love: “I love to run,” she writes, describing the feel of air on her skin, her heart pounding, sweat sliding down her ribs, and the way she once signed up for a 5K for charity even though a panicked inner voice insisted she would fail.

Erivo describes how, by slowly building up distance—sometimes only making it to the door, then the front step, then the street—she discovered that five minutes of effort still counts as running, and that “a little bit is enough” if you keep returning to it, which she explicitly links to any long-term creative or personal goal.

She writes in a later reflection that she has run “two official full marathons and four or five half marathons,” plus fifteen to twenty-five miles a week in training, and uses this to argue that consistency, not heroics, is what actually changes your sense of who you are and what you can carry.

From there, Part One moves into childhood.

In “What Did You Love as a Child?” she claims, “The seeds of who we truly are often are found in the memories of what we loved as a child,” and she recalls singing “Silent Night” as a five-year-old shepherd in a school nativity play, feeling “sparkly on the inside” as the audience clapped.

She remembers herself as a relentlessly curious kid—bossy, bubbly, humming while she ate, asking too many questions—until a beloved English teacher once sent her out of class for challenging her, a moment when she says she first understood what rage felt like because being told to be quiet felt like being told not to exist.

Later chapters in this section introduce Erivo’s mother and the women teachers who recognised her talent, gave her solos in classical works like Carmina Burana, and pushed her to see herself as a musician even when she flirted with a more “respectable” dream of becoming a spinal surgeon to fit in with high-achieving classmates.

Part One closes by showing that the first miles of any big life are mostly internal work: noticing what lights you up, refusing to swallow your questions forever, and daring to believe the people who say, “I see you,” instead of those who insist you are too much.

Part Two – Run the Second Ten Miles with Your Legs

If Part One is about self-knowledge, Part Two is about doing the work even when it’s gruelling, confusing or unfair.

These chapters follow Erivo through acting school, early roles, the grind of auditions, and the slow, often painful process of understanding how racism, classism and other people’s limited imagination shape the stories we are allowed to inhabit.

She writes about teachers and directors who pushed her, about the heartbreak of “no”s that turned out to be “yes”es in disguise, and about learning not to give people extra reasons to refuse her (“Do Not Give Them a Reason to Say ‘No’”) by being disciplined about her craft and preparation in an industry that already questions Black women’s competence.

There is a long thread about airports and anxiety: after The Color Purple closed, Erivo found herself flying constantly for concerts and gigs and, suddenly, began to dread every trip, sweating in security lines and spiralling about whether she would arrive on time, until therapy helped her realise that every flight was literally taking her further from London and the life she thought she was supposed to have.

In therapy at twenty-nine, she links that airport dread back to the moment her father abandoned her at sixteen on the Underground, a scene we see in more detail in an excerpt published in People: after a disagreement about a transit pass, he walked away and never came back, and she spent years trying to succeed hard enough to win him back before finally accepting that he “was never meant to be a dad.”

Part Two also covers the long road to Wicked: learning the music a decade before she ever auditioned, singing “Defying Gravity” for herself long before the world knew her as Elphaba, and later discovering that even record-breaking box office and global adoration do not insulate anyone from exhaustion, body pain or the quiet question, “How big a life are you really willing to live, and at what cost?”.

Part Three – Let Your Heart Carry You the Rest of the Way

The final section is where Simply More becomes most explicitly spiritual and political.

Erivo reflects on how the last miles of any marathon are run not by logic or willpower alone but by meaning: why you run at all, who you are running for, and what you believe about yourself and the world.

She writes about faith in a broad sense—raised Roman Catholic but no longer fully at home in institutional religion, she says the “most important part” of her faith is to be loving and kind and notes that she says “thank you” so often that “those two words on their own are a complete prayer.”

There is a powerful chapter on playing Jesus in Jesus Christ Superstar and the backlash she received from some Christians who called a Black, queer woman in that role “blasphemous,” which she interprets as revealing more about their belief that women are “lesser beings” than about God; it’s here that she writes, “Being more, even a little more than other people are comfortable with, is seldom easy.”

Another chapter, “Make a Pact,” details how she and Ariana Grande deliberately built a caring, equal partnership on the Wicked set—advocating for one another, asking for breaks together, sharing hard days over calls or visits—and how that mutual commitment “to live through the ongoing back-and-forth of life with each other” allowed them to defy the stereotype of competitive, catty women and instead “made each other family.”

By the end, Erivo circles back to the reader with a kind of benediction: she insists that “each of us has our own gifts to give” and that when we allow ourselves to be “simply more than what others expect,” we not only set ourselves free but also “shed our light on the path of those behind us.”

4. Simply More Analysis

From an analytical angle, the book’s biggest strength is its coherence: Erivo’s marathon metaphor is not a gimmick but a genuinely useful frame that threads through running, acting, queerness, family estrangement and faith without feeling forced.

Her core claim—that learning to be “simply more” of yourself is both inner work and daily discipline—is consistently supported by stories that show her failing, raging, doubting and choosing again, rather than by abstract advice alone, and those stories are grounded in recognisable psychological patterns like trauma responses, self-silencing and perfectionism that researchers have been documenting for decades.

There is also a clear alignment between what she preaches and how she lives publicly: interviews with Harper’s Bazaar and other outlets about her estrangement from her father, her decision to come out as queer in 2022, and her insistence on using her platform for LGBTQ+ visibility all echo the same philosophy you find in the book, which increases its credibility.

In terms of structure, the short, essay-like chapters and the constant return to reflective questions make the book easy to dip in and out of, but when you read it straight through, there is a clear narrative arc: from a little girl who hums while she eats and asks too many questions, to a teenager abandoned in a Tube station, to a woman who can stand in front of millions in green paint and still insist on listening to her own body first.

I think the book largely fulfils its stated purpose as “part-memoir, part inspirational manual for better living,” but it does so more through resonance and example than through checklists or exercises: you finish feeling seen and stirred rather than equipped with a ten-step plan, which is either a feature or a frustration depending on what you came for.

In that sense, Simply More sits closer to Glennon Doyle’s Untamed or Viola Davis’s Finding Me than to a cognitive-behavioural self-help manual: its power is in identification, in the sense that someone has finally articulated the inner life of those who get called “too much,” not in offering a rigid program.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

Personally, I found the early chapters on running and childhood almost disarming in their intimacy: there is something humble about a global star taking the time to describe the feel of sweat down her ribcage, or the sparkly, carbonated feeling of singing “Silent Night” as a five-year-old.

The repeated emphasis on body wisdom—listening to your breath on a run, paying attention to injuries, recognising when “limits” are actually what allows you to do more—felt refreshingly grounded in a self-help landscape that often glorifies overwork, and it quietly mirrors sports-psychology findings that sustainable performance hinges on rest as much as effort.

I was also deeply moved by the sections where she connects big cinematic moments (flying as Elphaba, leading a massive live choir, playing Jesus) to very ordinary fears—of being too loud, too queer, too demanding—and then uses those scenes to model how to feel rage without being consumed by it, a nuance psychologists also highlight as critical for mental health.

On the weaker side, there are places where the thematic, vignette-driven structure makes the timeline hazy, and if you are the kind of reader who wants to know exactly “what happened when,” you may find yourself wishing for a more traditional chronological spine.

There are also moments when the prose slides into the familiar language of inspiration—“everything is possible,” “the bigger the dream, the bigger the steps”—which, while sincere, can feel slightly generic compared with the vivid specificity of her best scenes; I sometimes caught myself wanting just one more concrete story where another line of motivational copy appeared instead.

Finally, because this is a book written by and about a globally successful performer, some readers in more precarious circumstances may feel a quiet distance: Erivo is honest about therapy, managers, publicists and film sets, but less able to speak to constraints like poverty, disability, or caring responsibilities, and she never pretends otherwise, which is honest but still leaves certain readers to translate her lessons into their own context.

6. Reception, Criticism and Early Influence

So far, the public reception of Simply More has been strongly positive, especially among fans who already know Erivo from Wicked and Harriet and who were eager for a more intimate look at her life.

According to booksellers like Barnes & Noble and Macmillan’s own listing, the book debuted as an “instant New York Times bestseller,” and UK retailers such as Waterstones and Browns emphasize its blend of “part memoir, part inspirational manual” and highlight reader reviews describing it as “inspiring, poignant and beautiful.”

Media outlets have mostly focused on two aspects: the raw honesty about her father’s abandonment and the way she writes about queerness and chosen family, with People running an exclusive excerpt about the Tube-station scene and Page Six summarising her admissions about “blackout rage” toward a manager and the emotional cost of being unapologetically herself.

Criticism so far has been limited and mostly mild; based on available reviews, some readers note that the short chapters and reflective tone can feel repetitive, and a few see the book as part of a broader wave of celebrity self-help, but I have not found credible sources alleging factual inaccuracy or harmful advice.

Given that the book is still very new, it is too early to measure long-term influence in hard numbers, but there are already signs of cultural impact: interviews about Simply More frequently appear alongside coverage of Wicked: For Good and Erivo’s album I Forgive You, and she explicitly frames all three projects as facets of one message—live authentically, even when that makes people uncomfortable.

I cannot yet point to academic citations or policy changes traceable to this book, but I can say that, based on early coverage and reader responses, it has quickly become a reference point for conversations about being “too much” as a Black queer woman in mainstream entertainment, in the same way that works like Untamed or Finding Me have shaped discourse about white and Black womanhood respectively.

7. Comparison with Similar Works

If you’ve read Michelle Obama’s Becoming, Viola Davis’s Finding Me or Glennon Doyle’s Untamed, you’ll feel some familiar notes in Simply More: all of these books trace a journey from external expectations to self-definition, and all contain a mix of family stories, career turning points and spiritual reflection.

What distinguishes Simply More is, first, its marathon frame, which gives it a physically grounded, process-focused texture; second, its explicit centring of being “too much” as a gendered and racialised accusation; and third, the very specific world it inhabits—West End stages, Broadway, Hollywood sets, BBC Proms nights and Oscar campaigns—with all the glitter and scrutiny those spaces entail.

Unlike more conventional celebrity memoirs that dwell heavily on behind-the-scenes gossip, Erivo’s anecdotes about Wicked and Jesus Christ Superstar are always in service of a lesson about boundaries, collaboration or courage: even her story about chafing harnesses in flying scenes becomes a meditation on listening to your body and respecting limits as “true power.”

Compared with more doctrinal self-help, the book also stands out for its openness about therapy and trauma: there is no suggestion that you can simply mantra your way out of abandonment wounds, only that understanding the roots of your anxiety can give you “a little bit more space,” a view that aligns closely with contemporary trauma-informed therapy.

From the perspective of your own site, probinism.com, which often pairs cultural critique with ethical and political reflection, Simply More would sit comfortably next to books and films that explore power, vulnerability and moral courage; at the time of writing I could not find a dedicated article on Erivo or this book there, but the book’s themes of resistance, faith and identity would clearly resonate with your existing interests.

8. Conclusion and Recommendation

Taken as a whole, Simply More: A Book for Anyone Who Has Been Told They’re Too Much is a warm, reflective and often piercing invitation to stop negotiating yourself down to fit other people’s comfort zones.

It won’t suit readers who need highly structured, research-heavy self-help, but for those who respond to story, metaphor and the sense of being personally addressed by someone who has walked through estrangement, fame and queer visibility, it offers an unusually embodied and realistic picture of what “being your full self” actually costs and gives back.

I would especially recommend Simply More to people who recognise themselves in the word “too”—too loud, too emotional, too ambitious, too queer, too Black for the spaces they inhabit—as well as to fans of Wicked who want to understand the woman inside the green paint and to anyone curious about how faith, art and activism can coexist without platitudes.

If you’re more interested in industry gossip, strict theology or tactical career advice, you may bounce off its gentle, meditative tone, but if you’re looking for a book that feels like a long run and a long talk with a fiercely honest friend, you’re squarely in its target audience.

In the end, what stayed with me most was Erivo’s quiet insistence that “you can run marathons”—not just on roads or stages, but in the private work of forgiving, grieving, coming out, setting boundaries and daring to believe that your “too much” might be exactly the right amount for the life you are meant to live.

If you have ever been told you’re too much, Simply More doesn’t just argue with that verdict; it quietly hands you back your own permission slip to be exactly, gloriously, simply more of who you already are.