If you’ve ever felt that “girls’ culture” is dismissed as trivial, Swifterature solves that problem by showing, with gusto and rigor, how Taylor Swift’s lyrics unlock the doors of English literature—and how English literature unlocks Swift.

Elly McCausland argues that Taylor Swift is not just pop phenomenon but a first-rate literary interlocutor—her songwriting actively converses with Shakespeare, Brontë, Chaucer, Fitzgerald and more, while teaching us to read stories, genres, and fame itself as shape-shifting narratives.

McCausland documents Swift’s own three-part songwriting taxonomy (quill, fountain pen, glitter gel pen) from Swift’s Nashville accolades; she connects Swift’s intertextual lyrics to The Great Gatsby, Jane Eyre, Romeo and Juliet, and Twilight; and she closes with Chaucer’s “House of Fame” to theorize celebrity narrative—“there is no man of great authority.”

Swifterature is best for readers who love Taylor Swift or literature—or both—and want an accessible crash course in genre, intertextuality, and feminist cultural criticism; not for readers seeking a simple listicle of literary references or an uncritical celeb biography.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

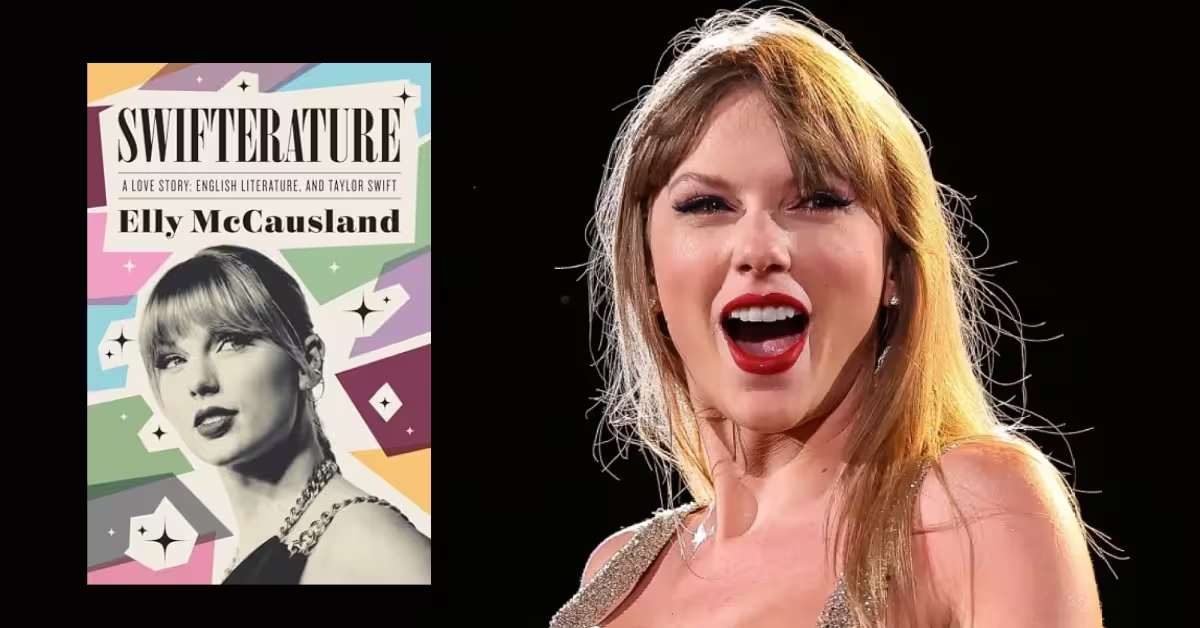

McCausland’s Swifterature: A Love Story: English Literature and Taylor Swift (Pegasus Books; hardcover ISBN 9781639369898; announced publication 4 November 2025) is structured in thirteen essays—of course—each taking a Swift lyric as a doorway into the literary canon and back again.

It sits at the crossroads of pop culture and the classroom: McCausland designed the viral Ghent University course English Literature (Taylor’s Version) in 2023, and the book distills both the backlash and the breakthroughs that followed.

According to Ghent’s Infinitum, the course made international headlines (The Guardian, CNN, Der Spiegel, the BBC); McCausland recounts the whirlwind of interviews and the hate mail that came with it—“It’s an auditorium, not a kindergarten.”

The purpose of the book is plain and provocative: to demonstrate that Swift’s lyrics are a vivid laboratory for literary analysis—and that the canon, in turn, illuminates Swift—while also critiquing the gendered snobbery that trivializes “girlish” tastes.

2. Background

McCausland frames Swift as a consciously literary songwriter who sorts her lyrics into “quill,” “fountain pen,” and “glitter gel pen”—a playful but revealing scaffolding that maps onto literary history from Emily Dickinson to confessional poetry. In Swift’s formulation, a “quill” song can sound like “a letter written by Emily Dickinson’s great-grandmother,” while “fountain pen” confessions feel “too brutally honest to ever send.”

Moreover, Swift has spent her career reinvention by genre—country to pop (Red, 1989), “goth-punk” on Reputation, then indie folk textures on folklore and evermore—mirroring literary form-shifts that keep narrative fresh. McCausland’s argument: Swift “flips the script” before the industry can replace her, a strategy she links to Romantic anxieties about originality and posterity.

3. Swifterature Summary

Elly McCausland argues that Taylor Swift is a consciously literary songwriter whose lyrics talk back to—and reanimate—the English canon. Swift reads, borrows, adapts, reframes and sometimes mischievously rewrites older stories (from Romeo and Juliet to Jane Eyre), while her career itself functions as a living lesson in genre, narrative, fame, and authorship.

McCausland’s classroom and this book model how “girls’ culture” can be a rigorous pathway into big, old books—without gatekeeping.

Across interlinked essays, McCausland moves from Swift’s own taxonomy of writing (“quill,” “fountain pen,” “glitter gel pen”) to case studies of intertext (Swift × Gatsby, Brontë, Shakespeare), then to theory (adaptation, authorship, and fame via Chaucer), and finally to classroom praxis and feminist media literacy.

Swift’s three-part taxonomy is sourced to Swift’s 2023 Nashville Songwriting Awards speech, where Swift explains that “quill” songs feel like a letter “written by Emily Dickinson’s great grandmother,” while “fountain pen” lyrics are “confessions… too brutally honest to ever send.”

By treating pop as literature and literature as pop-adjacent, Swifterature collapses a false divide. In practice, that yields better reading (you suddenly feel Chaucer), better listening (you hear Gatsby in “happiness”), and sharper cultural critique (how fame makes “truths” collide and mutate).

Highlights

- 2006 → the seed of the project. McCausland frames the book as the outcome of a “free association” mind-map around Swift’s lyrics running in her head “since 2006,” with the aim of making historical English literature widely accessible “with a little help” from Swift.

- Summer 2023 → course goes viral, controversy ensues. The Ghent University master’s course English Literature (Taylor’s Version) hit the media in 2023 and drew backlash, including a Belgian columnist’s complaint that students shouldn’t need Swift to reach Plath—an example McCausland uses to expose gendered cultural snobbery.

- 2023 Nashville Songwriting Awards → Swift’s writing taxonomy. Swift publicly divided her songs into “quill,” “fountain pen,” and “glitter gel pen,” giving McCausland a sturdy scaffold for reading Swift alongside the canon. (“Quill” might be sparked by Brontë and sound like “a letter… by Emily Dickinson’s great grandmother.”)

- Genre as self-reinvention strategy. Swift flips her story before the industry can replace her, shifting from country to Red/1989 pop, to “goth-punk” on Reputation, to indie textures on folklore/evermore.

- Intertext, not trivia. “Happiness” quotes The Great Gatsby; “invisible string” lifts the Jane Eyre red thread; “Love Story” converses with Romeo and Juliet; “Is It Over Now?” borrows the teen-gothic mood of Twilight.

- Adaptation as “beneficial mutation.” Drawing on Hutcheon/Bortolotti, McCausland reframes adaptations as mutations that help stories survive new environments—“every adaptation is an act of sanctioned infidelity”—locating Swift’s lyrical retellings within that evolutionary lens.

- Chaucer’s House of Fame → how narratives fly. In a buzzing palace where true and false stories merge in the doorway and “a man of great authority” never arrives, McCausland finds a medieval analogue for Swift’s palace of fame: “the guy on the screen becomes the guy on the Chiefs; the revenge story becomes the love story.”

- Against the “solitary genius” myth. The book dismantles the Romantic lightning-bolt cliché: creativity is collaborative labor—Swift literally shows drafts and voice notes; in 2023 she told Nashville she lives for the rare cloud of inspiration but then you “shape it like clay. Prune it like a garden.”

- Feminist through-line. From “mad woman” to “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?”, McCausland tracks how Swift leans into the “unlikable woman” and “too much” tropes to expose patriarchal expectations—and how caging metaphors (birdcage, vault, “from the vault”) annotate that pressure.

- Publication context. The edition is Pegasus Books, November 2025 (copyright), signaling a post-Eras, post-TTPD reflection that braids classroom practice, media debates, and Swift’s evolving oeuvre.

Detailed summary

Swift as narrator-of-narratives.

McCausland opens by showing that Swift’s protagonists “read” their lives as if already written—“I can read you like a magazine”—and that many Swift narrators anticipate an ending before the story begins (“don’t read the last page”). The point isn’t simply literary name-dropping; it’s that Swift’s speakers are literary thinkers who pattern the present by reference to shared story-templates.

The three pens: a working poetics.

The 2023 Nashville speech matters because it reveals Swift’s own craft categories. “Quill” songs are antiquated in diction and often lean on the canon (“Gatsby,” Jane Eyre, Romeo and Juliet). “Fountain pen” songs feel like sealed confessions—McCausland links this to the 1950s–60s confessional poets like Plath. “Glitter gel pen” (cheeky, maximalist pop) is both a vibe and an index of how a “girls’ culture” aesthetic can carry smart formal play.

Genre as survival tactic—and as literary form.

From Nashville country to 1989 synthpop to the indie hush of folklore/evermore, Swift “flip[s] the script” before gatekeepers flip it for her. McCausland underlines that we judge Swift by both what she tells and how she tells it, noting that critics have “warned [her] against departing from her original country stories,” even suggesting a man’s covers bestowed credibility—a textbook case of gendered genre-policing.

Intertextual Swift: case studies.

The book’s middle essays trace a network of intertexts:

- “Happiness” refracts The Great Gatsby’s ache of post-love separation;

- “Invisible string” borrows Brontë’s red thread of destiny;

- “Love Story” rewrites Shakespeare’s lovers toward a fairytale closure;

- “Is It Over Now?” borrows a Twilight mood to narrate dramatic attempts to be seen.

McCausland pushes beyond lists: every allusion is a lesson in how forms travel—how fairy tale and romance, for instance, haunt modern love songs.

Adaptation theory (why retellings matter).

Rather than score adaptations by “fidelity,” McCausland, following Linda Hutcheon and Gary Bortolotti, invites us to think biologically: stories survive by mutating.

That clears critical space for Swift’s miniature adaptations—“mad woman” as a Jane Eyre-era gothic for a generation fluent in the language of gaslighting; “tolerate it” as Rebecca-adjacent; “White Horse” splicing fairy tale with romance while remaining skeptical of chivalry.

The phrase she foregrounds—“every adaptation is an act of sanctioned infidelity”—is the book’s cheekiest and most clarifying maxim.

Chaucer’s House of Fame as master key.

Near the close, McCausland tours Chaucer’s pandemonium: a palace where all spoken things arrive; a twig-cage of “whispered, gossiped, murmured stories”; true and false tales jam in the door, merge, fly out together; a figure who “seemed… a man of great authority”—and then, nothing. Is that the joke?

That “there is no man of great authority”? From here she flips to Swift’s “palace of fame,” where truths re-order: “the guy on the screen becomes the guy on the Chiefs; the revenge story becomes the love story.” It’s the smartest frame in the book for understanding celebrity narrative churn.

Romanticism: lightning vs. labor, myth vs. method.

McCausland devotes an invigorating chapter to destroying the “solitary genius” myth. She shows how Romantics actually worked—late nights, collaboration (Dorothy Wordsworth feeding William’s lines), anxious labor.

Then she sets Swift beside them: Swift routinely publishes process (voice notes, demos), and in 2023 she told Nashville that the “magical cloud” is rare—you then “shape it like clay. Prune it like a garden.” It’s a quietly radical craft talk for a woman artist often asked, even in 2023, whether she really writes her songs.

Fame, posterity, and the anxiety of originality.

Romantics “were obsessed with fame” as afterlife, not chart position, and feared they’d be valued only posthumously. McCausland hears Swift thinking similarly about longevity and replacement—Time’s “moving target” mindset appears here as theory: speak now, or your words go “down in flames.”

It is, she suggests, where Swift is most Romantic—not the bolt of inspiration, but the worry about whether the words will last.

Feminism, “madness,” and the unlikable woman.

McCausland threads a careful feminist critique: Swift theatrically embraces “madness” and “unlikability” to expose how women’s feelings are delegitimized.

The book inventories Swift’s “cage” imagery—videos, props, “from the vault”—as a running metaphor for patriarchal constraints, while situating songs like “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” in a longer tradition of policing female ambition and affect as “too much.”

Pedagogy in public.

Because Swifterature grew from a course that the media both celebrated and dismissed, the book argues for pop-first pathways into the canon—pair The Wanderer’s grief with “Bigger Than the Whole Sky,” or explore ecocriticism via “ivy,” “willow,” “Out of the Woods”—so students can feel how metaphors travel across centuries. It’s a manifesto for teaching literary theory with curiosity and cultural humility.

Coda: the story leaves the author.

Late in the book, McCausland reflects that Swift (like Shakespeare, Brontë, and Barrie before her) releases stories that others will carry elsewhere: “Now and then I re-read the manuscript. But the story isn’t mine anymore.” That recognition powers Swifterature’s generosity: great stories live “a million little afterlives among new readers and generations.”

Swift’s songwriting is a laboratory where canon, fandom, and feminism meet. Her self-described “quill/fountain pen/glitter gel pen” modes are not a cute gimmick; they are a practical poetics that map onto centuries of literary form. Her discography demonstrates how genre is a narrative technology—how changing the “type of story” lets an artist survive a market that expects women to expire.

Her lyrics are not a scavenger hunt of references but active adaptations; in Hutcheon’s sense, they’re “beneficial mutations” that let stories fit new habitats. As Chaucer’s eagle shows him a hive of contradictory tales, so Swift’s palace of fame swarms with remixes, rerecordings, and reframings, where the true and the false stick together and fly out as one.

Against the Romantic myth of solitary lightning, McCausland reinstates creative labor, collaboration, and revision; Swift herself says the rare idea must be shaped “like clay… [and] pruned… like a garden.”

Across the book, McCausland also keeps the politics in view—how “girls’ culture” is mocked, how women’s ambition gets mislabeled madness, how caging imagery marks the limits placed on female expression. In the classroom, she turns these insights into methods that make old texts newly legible.

The closing recognition—that stories are never “ours” for long—explains why Swifterature isn’t trying to own Swift so much as to invite readers into the long conversation her songs already joined.

The upshot

Read Swifterature as a handbook for reading anything, not just Swift. It teaches you to 1) spot the story-templates shaping your own expectations; 2) see adaptation as vitality, not theft; 3) distrust any single “authority” in the hive of fame; 4) value revision, labor, and collaboration as the real engine of art; and 5) recognize how gendered expectations shadow every critical judgment of pop made by women, especially when that pop dares to speak in the language of literature.

If you only remember one image, keep Chaucer’s cage of stories in mind—and then picture Swift’s vaults, birdcages, and rerecordings, all of them proving McCausland’s point that our culture is built from stories that don’t stop moving.

4. Swifterature Analysis

McCausland’s contentions are supported by close readings and by Swift’s own meta-commentary. For example, happiness quotes The Great Gatsby; “invisible string” borrows Jane Eyre’s red thread; “Love Story” converses with Romeo and Juliet; and “Is It Over Now?” winks at Twilight’s teen-gothic. These intertexts aren’t trivia—they model how stories migrate across media and time.

She also examines Swift’s self-reflexive storytelling: in “Clara Bow,” Swift narrates her own celebrity through earlier starlets; in “Blank Space” and “Wildest Dreams,” the protagonist reads romance as if it were already authored, “don’t read the last page.” This awareness, McCausland argues, is Swift’s signature—an author who writes while studying the archive of stories she knows we know.

Crucially, Swifterature puts Swift’s “feminine extravaganza” into cultural and economic context.

Time named Swift 2023 Person of the Year, highlighting a three-part “summer of feminine extravaganza” (Swift’s Eras Tour, Beyoncé’s Renaissance, and Greta Gerwig’s Barbie), and the Eras Tour grossed an estimated $2.2–2.6 billion globally by late 2024–2025, selling over 10–11 million tickets and prompting economists to estimate nearly $7 billion in North American impact across 2023–2024.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

McCausland’s most compelling strength is how she uses Swift to reintroduce the canon without gatekeeping. Turning a Belgian columnist’s sneer—“It’s an auditorium, not a kindergarten”—into a pink-T-shirt slogan for her first class, she reframes “girlishness” as an analytic resource, not a liability; it’s both pedagogically savvy and disarmingly joyful.

As a reader, I found her chapters on grief and girlhood especially resonant. When she glosses “cardigan”—“when you are young, people assume you know nothing,” yet you may “know everything”—she captures Swift’s bittersweet defense of female adolescence as a legitimate archive of knowledge.

That said, the book occasionally promises a wider geopolitical reach than it delivers. In places where Swift’s global circulation intersects with class, race, or labor (tour logistics, ticketing inequities), I wanted a deeper dive; McCausland flags the “limits to that feminism,” but some chapters breeze past the political thorniness.

6. Reception

Reception-wise, Swifterature grew out of a course that drew BBC/CNN attention and sexist backlash in equal measure—proof, if we needed it, that the canon war is alive and well.

Ghent University’s own write-up lists the international coverage; McCausland’s foreword captures the deluge of interviews (Sweden, China, Dubai, Germany, Belgium, UK) and the trolling that followed (“go back to Brexit land”).

Influence may extend beyond literature departments. With Swift’s Eras Tour setting industry records—$2.2B+ gross and more than 10 million tickets sold—and with Time’s Person of the Year piece framing a “feminine extravaganza,” Swifterature captures a wave that is reshaping how universities and the media talk about fandom, femininity, and cultural capital. (AP News)

7. Swifterature‘s most illuminating moves

First, McCausland’s Chaucer move is genius. In a vivid retelling of The House of Fame, she shows how stories “whispered, gossiped, murmured” fly in and out of a cage, merge, mutate, and claim competing truths—then she turns to Swift’s own palace of fame, where “the guy on the screen becomes the guy on the Chiefs; the revenge story becomes the love story.” The kicker: “there is no man of great authority.” It’s a medieval mirror for a modern media storm.

Second, she punctures the Romantic “lightning bolt” myth by quoting Swift’s 2023 Nashville remarks: inspiration is rare; real art is shaped “like clay,” “pruned… like a garden.” That proverb alone belongs on a studio wall.

Third, she reads Swift’s “cardigan” as an ambivalent coming-of-age text—part Peter Pan, part feminist manifesto—while tying it to the sexist dismissal of her own course; the juxtaposition lands.

Fourth, she demonstrates that Swift’s “fountain pen” mode overlaps with the confessional tradition (Plath, et al.), which helps explain why fans experience Swift’s lyrics as intimate letters.

Fifth, she shows how Swift’s career-long reinventions (“harder to hit a moving target”) answer a market that “actively” seeks to replace female artists—placing Swift within a feminist critique of industry churn and the gendered cost of originality.

8. Conclusion

I recommend Swifterature wholeheartedly to general readers, teachers, and students: it’s a smart, generous primer on how to read art across centuries—through pop, and back again. If you’re a Swiftie, it will deepen your listening; if you’re literature-curious but canon-shy, it offers a gentle bridge; if you’re a skeptic of pop scholarship, it’s the best argument for why the canon should meet the stadium.

Recommendation

Read Swifterature if you’re a Swiftie wanting to level-up your listening, a student who suspects the canon can be fun, a teacher craving active-learning ideas, or a critic itching for a better debate than “high vs. low.” If you want just a gossip-adjacent list of references or a pious hymn to celebrity, this book will frustrate you—in the best way—by making you think.