Last updated on September 2nd, 2025 at 02:22 pm

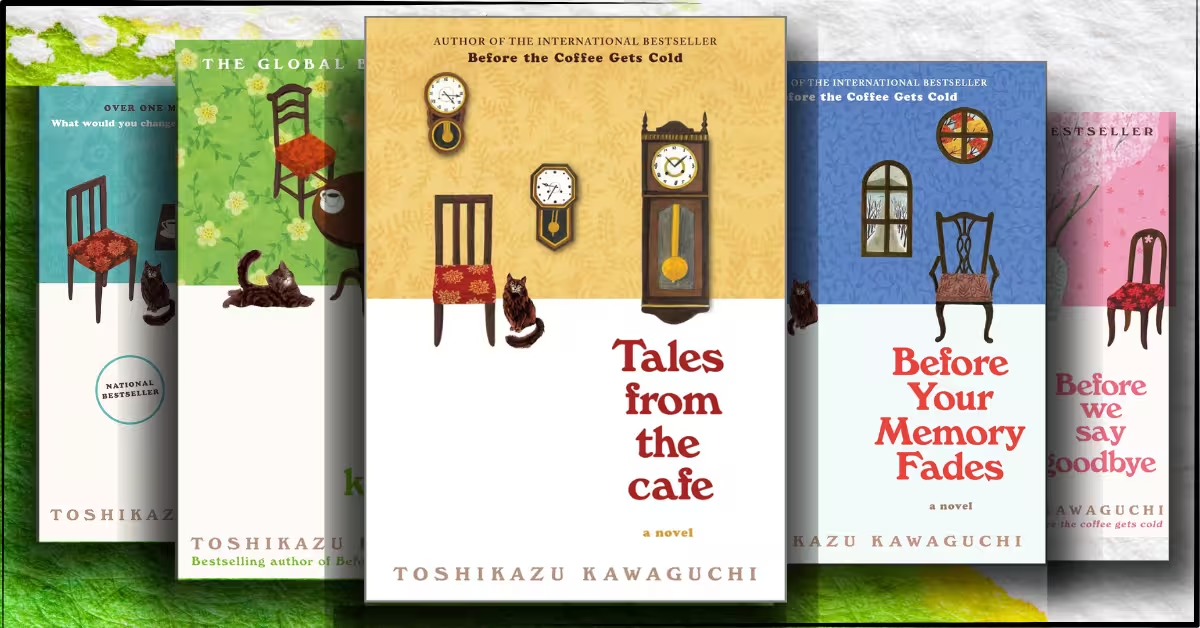

Tales from the Cafe is the second instalment in Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s internationally acclaimed time-travel series, following the bestselling Before the Coffee Gets Cold. Originally published in Japanese as 続・コーヒーが冷めないうちに, it was translated into English by Geoffrey Trousselot and released in 2020 by Picador.

Kawaguchi, born in Osaka in 1971, is a playwright and producer who gained early recognition for his theatrical works, including the stage version of Before the Coffee Gets Cold, which won the Suginami Drama Festival grand prize. His seamless transition from stage to page reflects a deep understanding of character, dialogue, and emotional timing — skills that resonate profoundly in this novel.

At its heart, Tales from the Cafe is a work of contemporary Japanese fiction tinged with magical realism. It sits comfortably in the niche of “emotional fantasy” — stories grounded in the mundane yet infused with an element of the impossible. Here, the impossible takes the form of a basement café in Tokyo named Funiculi Funicula, where patrons can travel back in time under a strict set of rules.

This isn’t a story about changing fate; rather, it’s about confronting it. The book explores the Japanese cultural ethos of mono no aware — the bittersweet awareness of impermanence — while weaving in universal questions about love, loss, regret, and closure. It belongs to a growing subgenre of reflective, character-driven time travel narratives that eschew paradoxes in favour of emotional resolution.

My overall impression of Tales from the Café is that it offers a rare literary alchemy: it is both gentle and profound, deceptively simple in plot yet rich in emotional texture. Kawaguchi’s strength lies in creating vignettes that work individually as short stories yet interconnect seamlessly into a unified narrative.

Unlike many time travel tales that centre on altering outcomes, this book finds power in acceptance. The limitation that “no matter what you do, the present won’t change” transforms the premise from a science-fiction puzzle into a philosophical mirror.

It is this reframing — where the journey matters more than the destination — that makes Tales from the Café a standout in modern Japanese literature.

Table of Contents

1. Background

The world of Tales from the Café unfolds in a small, dimly lit basement coffee shop called Funiculi Funicula, tucked away in a quiet side street near Jimbocho Station, Tokyo. On the surface, it’s an unremarkable place — low ceilings, antique clocks that never tell the same time, a faint sepia glow from shaded lamps, and the comforting aroma of freshly brewed coffee. But it has become the centre of a peculiar urban legend: here, under the right conditions, you can travel back in time.

The idea of this magical yet strictly rule-bound café originates from Kawaguchi’s own stage play. The success of Before the Coffee Gets Cold turned that concept into an international phenomenon, and Tales from the Café builds upon it by introducing new stories, each framed within the same mystical boundaries:

- You can only meet people who have visited the café.

- No matter what you do, the present will not change.

- Only one special seat allows time travel — and it’s usually occupied.

- You cannot leave your seat while in the past.

- You must return before the coffee gets cold — or remain a ghost, forever stuck in the café.

These rules aren’t just plot devices; they’re moral constraints. They ensure that time travel is not an escapist fantasy but an emotional test. By imposing inevitability, Kawaguchi forces characters (and readers) to face the deeper question: If you cannot change the outcome, is the journey still worth it?

Culturally, this narrative fits into Japan’s tradition of “quiet magic realism,” where supernatural elements slip almost unnoticed into everyday life. Unlike Western time travel tales that lean heavily on paradoxes or alternate timelines, this story treats the past as a space for reconciliation rather than revision.

Tales from the Café was published in Japan at a time when reflective, healing fiction (iyashikei shōsetsu) was gaining traction — novels meant to soothe, not just entertain. Globally, it arrived in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic had magnified themes of loss, connection, and the fragility of life, giving its message an added layer of relevance.

2. Summary of the Book

Plot Overview

Tales from the Café is composed of four interlinked stories, each set in the same magical Tokyo coffee shop — Funiculi Funicula — where patrons can travel back in time under unbreakable rules. Every story examines a different facet of human regret, love, and closure, framed by the impossibility of altering the present.

Story I – Best Friend

Gohtaro Chiba, a stocky former rugby player, has raised his daughter Haruka alone for twenty-two years. She believes her mother died of an illness, but the truth is that Haruka is not his biological daughter — she is the child of Gohtaro’s best friend, Shuichi Kamiya, and Shuichi’s wife, Yoko.

Two decades earlier, Gohtaro’s life collapsed when he was forced into bankruptcy after co-signing a failed business loan. Homeless and destitute, he encountered Shuichi outside Funiculi Funicula. Shuichi, instead of turning away, invited him inside, heard his story, and offered him a job at his diner. This act of kindness rekindled Gohtaro’s hope. But tragedy struck a year later when a car accident killed both Shuichi and Yoko, leaving their infant daughter orphaned. Determined to repay his friend’s kindness, Gohtaro raised Haruka as his own.

Now, with Haruka engaged to a man named Satoshi Obi, Gohtaro struggles with the lie he’s kept. She will soon discover the truth when she registers her marriage. Gohtaro comes to Funiculi Funicula with a plan: travel back in time to meet Shuichi and record a wedding message from her real father.

The journey is surreal. When Shuichi returns from the café toilet, he immediately recognises something extraordinary has happened. His natural perceptiveness allows him to guess that Gohtaro has come from the future. The reunion is emotional — Shuichi is overjoyed to see that Gohtaro has survived the hardships of the past decades. However, as they record the message, Shuichi sees through Gohtaro’s pretence: the future version of himself will not be at Haruka’s wedding, because he will be dead.

Rather than dwell on that truth, Shuichi pours his love into the message, speaking of Haruka’s birth under blooming sakura, his joy in holding her, and his wish for her lifelong happiness. The coffee cools, and Gohtaro returns to the present with the recording — a bridge between past love and present truth.

Story II – Mother and Son

The second tale centres on Kotake, a nurse whose husband Fusagi suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. Fusagi had visited the café in Before the Coffee Gets Cold, intending to go back in time to give Kotake a letter explaining his diagnosis, but lost his nerve. In this sequel, the focus shifts to another mother-son pair: Yukari and Kazuya.

Yukari is terminally ill and estranged from her grown son Kazuya due to years of miscommunication and resentment. She wishes to go back in time to a day when he was still a boy, full of innocent warmth, before life’s disappointments drove a wedge between them. She chooses to see him not to change anything — she knows she can’t — but to feel once more the love that had not yet been buried under years of hurt.

In the café’s sepia-lit stillness, Yukari revisits a day from Kazuya’s childhood. She watches him chatter excitedly about soccer, sees his bright eyes light up when she praises him, and feels the pure bond they once shared. She does not try to fix the rift; she simply lets herself feel the joy and stores it like a final keepsake. The return to the present is bittersweet — nothing has changed, but her heart is lighter.

Story III – Lovers

This story follows Reiko, a woman who lost her boyfriend Takashi in a boating accident. Years later, she still carries unresolved feelings and a box of his belongings she has never been able to sort through. The rule that “the present will not change” has kept her from visiting the past, fearing that reliving their moments might reopen wounds rather than heal them.

When she finally sits in the time-travel seat, she chooses a quiet afternoon when they were still together. Takashi greets her with the easy charm she remembers, unaware of the tragedy that awaits him.

They talk about small things — books, the café’s coffee, future plans that Reiko knows will never come true. She fights the urge to warn him, to scream for him not to go on that trip. Instead, she savours the moment, letting his laughter and voice etch themselves into her memory anew.

In returning, Reiko feels the ache of loss but also a sense of completion. The visit hasn’t erased her grief, but it has transformed it into gratitude.

Story IV – Married Couple

The final tale centres on Nagare Tokita, the café owner, and his cousin Kazu, the stoic waitress who alone can pour the coffee for time travel. The emotional arc unfolds around Yaeko Hirai, a spirited woman who runs a bar nearby. Hirai had been engaged years earlier but broke it off abruptly, sending her fiancé into a spiral that ended in his early death.

When his younger brother comes to tell her of his passing, Hirai realises she has been carrying guilt for decades. The café offers her a chance to see her fiancé one last time. In the past, she finds him happy, healthy, and still in love with her. They talk lightly, avoiding the break-up altogether, but beneath her calm exterior Hirai is saying goodbye. When she returns, she closes her bar early and walks through the cherry blossoms, feeling the quiet peace of release.

Interconnected Threads

While each story is self-contained, the characters’ lives overlap through the café’s daily rhythms. Kazu, with her unreadable expression and unerring ability to keep emotional distance, acts as a guardian of the café’s rules and an observer of human frailty.

Nagare maintains the café’s steady hum, offering both practical help and silent understanding. Even the ghostly woman in the white dress — forever stuck because she let her coffee go cold — serves as a reminder that the past is a gift to be handled with care.

Setting

The setting of Tales from the Café is almost a character itself. Funiculi Funicula’s basement location, antique clocks, earthen plaster walls, and subdued lighting create a timeless bubble. The absence of windows and the unchanging décor give the café an eternal, dreamlike quality, where the outside world’s noise is muted.

The space is designed not for distraction, but for contemplation — a sanctuary where moments are suspended between sips of coffee and the ticking of mismatched clocks.

3. Analysis

3.1 Characters

Kawaguchi’s storytelling strength lies in crafting characters who, despite being bound by fantastical circumstances, feel deeply human. Each figure in Tales from the Café carries emotional weight — whether they are the focus of a story or a supporting presence.

Gohtaro Chiba

Gohtaro is the moral centre of the opening story, “Best Friend.” A former rugby player whose life crumbled due to financial ruin, he embodies resilience shaped by gratitude. His decision to raise Haruka as his own — while withholding her true parentage — is born of loyalty to his late friend Shuichi. His journey back to the past is less about himself and more about preserving Haruka’s emotional security. The depth of his character comes from the tension between his steadfast love and the moral discomfort of his decades-long lie. His stocky build, straightforward speech, and occasional awkwardness make him relatable, a “quiet hero” whose biggest victories are personal, not public.

Shuichi Kamiya

Shuichi is both a character and a memory. In the past, he is perceptive, sharp-witted, and emotionally intelligent — qualities that earned him the nickname “Shuichi the Seer” on the rugby field. His immediate recognition that Gohtaro has come from the future underscores his intuitive nature. What makes Shuichi compelling is his ability to face the unspoken truth — that he will not live to see his daughter’s wedding — without bitterness, instead using his brief reunion to give her a gift of love in words.

Kazu Tokita

The enigmatic waitress is the only one who can pour the coffee that enables time travel. She maintains an impassive exterior, never overly moved by customers’ emotional stories, yet her subtle acts — such as giving a child a free drink or gently managing Miki’s enthusiasm — reveal a compassionate core. Kazu’s role is both gatekeeper and silent witness; she enforces the rules but never interferes in customers’ choices, embodying the book’s theme that closure must be self-earned.

Nagare Tokita

The café’s owner, Nagare, provides a steady presence. His towering frame and calm authority contrast with the fragile, fleeting emotions his patrons experience. Though seemingly detached, he has a quietly protective streak, evident when he prevents Gohtaro from standing up and inadvertently ending his time in the past. His relationship with Miki and Kazu offers a grounding domesticity to the otherwise ethereal setting.

Miki Tokita

Nagare’s young daughter is a bright, curious counterpoint to the café’s subdued tone. Her playful use of “moi” to refer to herself and her uninhibited questions — such as bluntly asking customers why they want to return to the past — bring a dose of innocence and levity. Miki represents the unfiltered perspective that contrasts with the guarded emotional landscapes of the adult characters.

Supporting Figures (Reiko, Yaeko Hirai, Yukari, Kazuya)

Each of these supporting characters brings a unique emotional challenge to the café. Reiko’s lingering grief over Takashi, Hirai’s long-held guilt over her broken engagement, and Yukari’s yearning to reconnect with her son all illustrate different shades of human regret. They are written with enough specificity to feel real but with enough universality for readers to recognise themselves in their struggles.

Alright — here’s 3.2 Writing Style and Structure for Tales from the Café.

3.2 Writing Style and Structure

Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s writing in Tales from the Café is deceptively simple — a style that mirrors the quiet atmosphere of Funiculi Funicula itself. The prose is stripped of ornamentation yet manages to evoke vivid sensory impressions: the aroma of siphon-brewed coffee, the muted glow of shaded lamps, the soft creak of antique furniture. This minimalism is deliberate; it allows emotional beats to land without distraction, much like a stage set that frames rather than competes with the actors.

Narrative Techniques

- Episodic Structure:

The novel is divided into four self-contained yet interconnected stories, each with its own protagonist and emotional arc. This structure mirrors the flow of customers through the café — each with a unique reason for wanting to revisit the past — while maintaining a cohesive thematic through-line. - Rule-Bound Magical Realism:

The strict rules of time travel serve as both narrative constraints and thematic anchors. By repeating these rules for each new character, Kawaguchi reinforces the inevitability of events and shifts the reader’s focus from “what will change?” to “what will be learned?” - Stage Play Origins:

The dialogue-heavy interactions and limited setting reflect the story’s theatrical roots. Conversations carry the narrative forward, and subtle physical cues — a pause, a glance, a sip of coffee — often convey more than exposition could.

Use of Literary Devices

- Symbolism of Coffee:

The coffee’s temperature acts as a literal countdown, an embodiment of impermanence. The moment it goes cold, the chance to be in the past is gone — a tangible representation of fleeting opportunities in life. - Repetition and Echoes:

Phrases and motifs recur across stories — such as the sound of the cowbell over the door (clang-dong), the description of the café’s clocks, or the caution to “drink the coffee before it gets cold.” This creates a meditative rhythm, reinforcing the interconnectedness of experiences. - Contrast Between Tone and Content:

The prose maintains a calm, almost matter-of-fact tone even when dealing with heartbreak or death. This tonal restraint heightens emotional impact, much like a quiet confession can be more powerful than a shouted declaration.

Pacing

Kawaguchi balances the stillness of the café with the urgency of time travel. The pacing slows during character introspection, then tightens as the coffee cools — creating a natural tension that keeps readers anchored in the moment. Because each story covers only the span of a single café visit (with flashbacks woven in), the narrative never overstays its welcome.

Alright — here’s 3.3 Themes and Symbolism for Tales from the Café.

3.3 Themes and Symbolism

Kawaguchi’s Tales from the Café is more than a sequence of time-travel stories — it’s a meditation on life’s unchangeable truths and the emotional choices people make when faced with them. The novel’s magic lies not in altering the past but in reframing it, offering comfort without illusion.

1. Acceptance Over Alteration

The central rule — nothing you do in the past will change the present — flips the usual time-travel narrative on its head. Here, returning to the past isn’t about rewriting fate but reconciling with it. Each character must choose to value the emotional experience itself rather than the possibility of a different outcome.

Example: Gohtaro’s trip to see Shuichi doesn’t erase Haruka’s orphanhood, but it gives her a recorded memory of her father’s love.

2. The Weight of Regret

Every patron in Funiculi Funicula carries some form of regret — an unsaid goodbye, an unresolved conflict, an unshared truth. Kawaguchi presents regret as a universal human burden, but one that can be transformed through acknowledgment.

Symbolically, the act of sitting in the chair and drinking the coffee becomes a ritual of facing what haunts you, knowing you can’t undo it.

3. The Impermanence of Life (Mono no Aware)

The fleeting nature of warm coffee mirrors the impermanence of human connections. The Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware — the bittersweet appreciation of transience — is embedded in every cup. Cherry blossoms, scattered throughout the novel’s imagery, reinforce this sense that beauty and loss are intertwined.

4. Love Beyond Time

Whether romantic, familial, or platonic, love in Tales from the Café transcends death and years. Shuichi’s wedding message to Haruka, Yukari’s quiet joy in seeing her young son, and Reiko’s bittersweet visit with Takashi all underscore the theme that love’s value lies in presence, not permanence.

5. The Café as a Liminal Space

Funiculi Funicula is more than a setting — it’s a threshold between past and present, life and memory. Its windowless, timeless design suggests a place outside ordinary reality, where rules are rigid but emotional possibilities are infinite. The ghost in the white dress serves as a living (or lingering) reminder of what happens when one clings too long to the past.

6. The Role of Witness

Kazu’s detached yet constant presence embodies another subtle theme: closure often requires someone simply to witness your story. She doesn’t judge, advise, or intervene — her role is to facilitate, then step back, allowing each person to own their experience.

3.4 Genre-Specific Elements

Magical Realism with Japanese Sensibility

Tales from the Café firmly sits within the realm of magical realism, but unlike its Latin American counterparts — which often use the supernatural to critique political or social realities — Kawaguchi’s magic is intimate, domesticated, and emotionally focused. The time travel is bounded by specific, even inconvenient rules, keeping the fantasy grounded in everyday logic. This reflects a Japanese literary tendency to weave the supernatural seamlessly into ordinary life, inviting readers to accept the impossible as quietly plausible.

World-Building Through Repetition

The “world” of Funiculi Funicula is small — a single room, a handful of recurring characters, and a set of rules. Yet through repetition, the café becomes richly textured. Every clang of the cowbell at the door, every mismatched clock, every reminder to “drink the coffee before it gets cold” reinforces the reader’s familiarity, turning the café into a place that feels almost visitable.

Dialogue-Driven Intimacy

Because the setting is so confined, dialogue becomes the main vehicle for storytelling. Conversations are carefully paced, often mirroring the measured pouring of coffee. Pauses, half-finished sentences, and understated remarks leave space for the reader’s emotions to fill in. This restraint is a hallmark of Japanese drama and lends the book its quiet power.

Emotional Pacing vs. Action Pacing

In many genres, time travel is paired with urgency and high-stakes action. Here, urgency comes not from averting disaster but from savouring the finite — the cup cooling, the moment slipping away. The pacing slows to let emotions deepen, then compresses as the coffee approaches coldness, creating a rhythm that mirrors the characters’ internal states.

Who This Book Is For

- Fans of Gentle, Reflective Fiction: Readers who appreciated works like The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide or Strange Weather in Tokyo by Hiromi Kawakami will find a similar understated poignancy here.

- Magical Realism Enthusiasts: Especially those who prefer emotionally grounded magic rather than elaborate speculative systems.

- Readers Seeking Comfort in Literature: Its themes of reconciliation, acceptance, and love make it an iyashikei (healing) novel, offering emotional balm in difficult times.

- Book Club Picks: The novel’s universal themes and discussion-friendly structure make it ideal for group reading.

Alright — here’s 4. Evaluation for Tales from the Café.

4. Evaluation

Strengths

- Emotional Precision – Kawaguchi captures complex feelings — regret, gratitude, love, and loss — with simple language that cuts straight to the heart. The lack of melodrama makes the emotional beats feel earned rather than manufactured.

- Unique Premise with Grounded Rules – The five unbreakable rules of time travel give the novel structure and thematic weight. Instead of chasing paradoxes, the book uses constraints to deepen character arcs.

- Atmosphere as Character – Funiculi Funicula is so vividly evoked that it becomes as memorable as any protagonist. Its dim lighting, mismatched clocks, and steady rituals create an immersive, almost meditative reading space.

- Interconnected Stories – While each tale can stand alone, recurring characters and the shared setting give the novel a sense of cohesion and community.

- Cultural Resonance – The blend of magical realism and mono no aware (awareness of impermanence) gives the book a distinctly Japanese literary flavour, while still feeling universal.

Weaknesses

- Predictable Emotional Arcs – Once the reader understands the rules and rhythm, the outcomes of later stories can feel somewhat anticipated.

- Limited Setting Scope – The confined location, while atmospheric, may feel restrictive to readers craving variety in setting or action.

- Sparse Character Backstories – Side characters sometimes lack depth beyond their immediate emotional conflict, which could leave some readers wanting more.

- Translation Simplicity – The English translation is clear but occasionally flattens the subtle lyricism that might be present in the original Japanese.

Impact

The emotional resonance of Tales from the Café lies in its timing as much as its storytelling. Published in English in 2020, it reached readers during a period of global uncertainty, when many were reflecting on lost opportunities and unchangeable pasts.

Its message — that we can’t alter history but can change our relationship to it — found a receptive, even grateful audience. Many readers have described it as a “healing” book, one that invites quiet introspection rather than adrenaline-fuelled escapism.

Comparison with Similar Works

- Before the Coffee Gets Cold (Kawaguchi) – The first book introduces the rules and core characters, while Tales from the Café expands the emotional range, offering more varied relationships (friends, parents, lovers, spouses) rather than focusing mostly on romantic or familial ties.

- The Midnight Library (Matt Haig) – Both explore alternate life possibilities, but Kawaguchi’s work is more grounded in acceptance rather than imagining fully changed realities.

- Hiromi Kawakami’s Fiction – Similar understated emotional tone and emphasis on everyday magic in quiet Japanese settings.

Reception and Criticism

Critics have generally praised Kawaguchi for crafting a “gentle, uplifting” narrative that avoids sentimentality despite its emotional premise. Some have noted the theatrical origins of the prose, observing that the book reads almost like a stage play in novel form — a strength for those who enjoy dialogue-driven storytelling, but potentially too static for action-oriented readers.

Adaptation

While Before the Coffee Gets Cold was adapted into a Japanese film, Tales from the Café has yet to receive a direct screen adaptation as of 2025. However, its episodic structure and strong visual setting make it a natural candidate for a limited series format, perhaps even one that could integrate stories from both books.

5. Personal Insight with Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading Tales from the Café feels like sitting in on a quiet philosophy seminar disguised as a short story collection. Its lessons resonate not only on a personal level but also in broader educational and societal contexts.

The book’s most powerful takeaway is that closure is not about erasing mistakes or altering outcomes, but about reframing them.

In psychology, this mirrors the concept of acceptance-based coping — a strategy linked to better mental health outcomes, particularly in situations beyond one’s control. A 2019 study published in Journal of Happiness Studies found that people who practiced acceptance reported 23% higher life satisfaction compared to those who dwelled on “what if” scenarios.

Learning Through Limits

The five strict café rules are a narrative reminder that limitations can spark deeper creativity. In educational psychology, constraint-based learning is known to enhance problem-solving skills because it forces individuals to operate within boundaries. The characters’ emotional journeys are richer precisely because they can’t change reality — they must instead mine meaning from the experience itself.

For students of literature and culture, Tales from the Café is an accessible gateway to understanding mono no aware, a central aesthetic in Japanese art and writing. Recognising impermanence and finding beauty in it isn’t just a literary device; it’s a cultural worldview that informs everything from haiku poetry to modern anime. Incorporating such texts into comparative literature curricula fosters cross-cultural empathy and interpretive skills.

Relevance to Post-Pandemic Reflection

Released internationally in 2020, the novel’s meditations on loss and reconnection found special resonance during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many were grieving missed milestones — graduations, weddings, final goodbyes.

UNESCO reported that 1.6 billion learners worldwide were affected by school closures in 2020. In such times, literature like Tales from the Café provides a safe emotional space to process the reality that some chapters in life will remain unwritten.

Practical Educational Applications

- Creative Writing Courses – Students can use the café’s rule-bound world as a model for building their own “closed-system” settings, encouraging plot and character development through constraints.

- Counselling and Therapy Training – Passages can be used in narrative therapy sessions to help clients explore their own “unfinished conversations” without the pressure of resolution.

- Ethics and Philosophy Classes – The novel offers fertile ground for debates about determinism, free will, and the ethics of truth-telling in relationships.

6. Conclusion

Tales from the Café is not a story about rewriting the past — it is a gentle, resonant reminder that the value of our memories lies in experiencing them fully, not in changing their outcome. Kawaguchi’s quiet, dialogue-driven style makes the book feel like a shared secret between writer and reader, a whispered truth over a warm cup of coffee.

The novel’s strength is in its restraint: by imposing unchangeable rules on time travel, Kawaguchi shifts the narrative from what if to what now. Each vignette reminds us that while the past is fixed, the meaning we take from it is not.

Recommendation

This book is especially suited for:

- Readers who enjoy character-driven magical realism over action-heavy time travel.

- Those drawn to reflective, healing literature (iyashikei shōsetsu) that offers emotional comfort without oversimplifying life’s complexities.

- Book clubs and discussion groups, given its layered themes of regret, acceptance, and the ethics of truth-telling.

- Students of Japanese literature and culture, as an accessible entry into mono no aware and understated storytelling.

Why It’s Worth Reading

In an era obsessed with productivity, speed, and “fixing” mistakes, Tales from the Café offers something rare — permission to pause, revisit, and simply be with the moments that have shaped us. It suggests that the heart’s timeline is not bound by linear time: a conversation from twenty years ago can still echo, a goodbye can still be said, a love can still be felt.

And maybe, in its quiet way, that’s all the change we ever truly need.