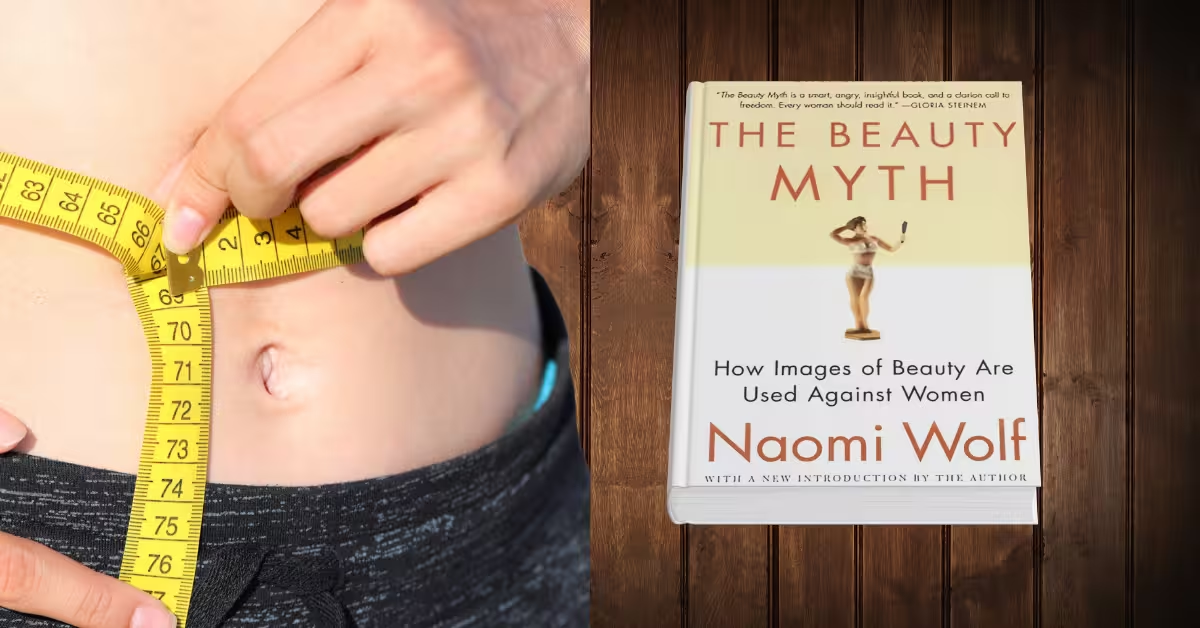

In 1990, Naomi Wolf published a provocative, culture-shifting work that would become a cornerstone of contemporary feminist literature: The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. Originally published in the United States, the book is updated that revisited the myth through the lens of a new millennium.

Wolf, a Rhodes Scholar and Yale graduate, emerged in the 1990s as a new voice in feminist discourse. She was young, assertive, articulate, and deeply engaged with the media’s evolving portrayal of women.

With The Beauty Myth, she didn’t just critique the media’s objectification of women—she reframed beauty itself as an economic, political, and cultural tool used to suppress women’s autonomy.

The book was a lightning rod, generating both acclaim and fury, embraced as a third-wave feminist manifesto by some, and sharply critiqued for statistical inaccuracies and generalizations by others.

As Wolf asserts, “The more legal and material hindrances women have broken through, the more strictly and heavily and cruelly images of female beauty have come to weigh upon us” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction).

At its core, the book argues that just as women began to achieve greater freedom, autonomy, and visibility in public life, a new invisible barrier emerged in the form of idealized beauty. Unlike the oppressive laws and mores of the past, the beauty myth operates through self-regulation, advertising, internalized guilt, and omnipresent media narratives.

This is not merely a book about fashion or magazines—it is an indictment of systems. It tackles how images of beauty function across five institutions: work, culture, religion, sex, and hunger. These realms become battlegrounds where the myth maintains its stranglehold on women’s psyches and bodies, turning physical appearance into a moral and professional currency.

Wolf’s central thesis is both personal and systemic: the “beauty myth” is a political weapon used to undermine women’s growing social power by obsessing them with physical appearance.

She writes, “More women have more money and power and scope and legal recognition than we have ever had before; but in terms of how we feel about ourselves physically, we may actually be worse off than our unliberated grandmothers” (The Beauty Myth, p. 10).

In effect, Wolf argues that beauty has become the new ideology—one no less powerful than religion, motherhood, or the feminine mystique of previous generations.

Table of Contents

Background

To appreciate The Beauty Myth, it’s essential to place it within its historical and feminist context. The book was published in 1990, just after a period Wolf calls “The Evil Eighties”—an era dominated by Reaganism, cultural conservatism, and antifeminist backlash.

As Wolf recalls, “Women were being told they couldn’t ‘have it all.’” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction).

This backlash was well-documented in Susan Faludi’s Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, a companion volume to Wolf’s analysis. Feminism was being publicly discredited, rebranded as extreme, angry, unfashionable. Beauty ideals, however, were not discredited. Instead, they were intensified—mutated by new media saturation, advertising capitalism, and cosmetic technologies.

Wolf drew inspiration from foundational feminist texts such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, both of which highlighted the psychological and social costs of femininity.

But unlike her predecessors, Wolf was writing from within the media machine itself—at a time when beauty, thinness, and youth were aggressively marketed commodities and identity markers.

She wasn’t alone in noticing the shift. As she notes, “We were just coming out of what I have called ‘The Evil Eighties’… Reagan had just had his long run of power, the Equal Rights Amendment had run out of steam, women’s activists were in retreat” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction).

This context is crucial because The Beauty Myth is not a standalone argument. It is a response to a reaction—a cultural reaction to feminism’s gains. And it offers a framework for understanding why beauty standards became more rigid at the exact moment that women seemed to be breaking free.

Extended Summary of The Beauty Myth

Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth is a masterfully structured feminist critique that unfolds across seven thematic chapters—each examining how the “myth” of beauty infiltrates different dimensions of modern life.

Wolf organizes her arguments not chronologically, but thematically, focusing on how beauty functions as an ideology in Work, Culture, Religion, Sex, Hunger, and Violence, before offering a vision for change in Beyond the Beauty Myth.

Wolf’s overarching claim is that the “beauty myth” is not about aesthetics or health, but about power and control. She contends that just as women have gained material freedoms, a new psychological prison has been constructed around appearance. This beauty myth, she writes, “is not about women at all. It is about men’s institutions and institutional power” (The Beauty Myth, p. 12).

The Beauty Myth (Opening Chapter)

Wolf opens the book by directly confronting the core fiction of the beauty myth: that beauty is universal, timeless, and rooted in biology. She dismantles this assumption by arguing that “beauty” is a currency system, not a truth:

“Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard. Like any economy, it is determined by politics.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 12)

This system, she argues, thrives on competition between women, making them divided and distracted, vulnerable to external approval, and internally driven to self-monitor their appearance. The myth pressures women to embody impossible standards—“a face without pores, asymmetry, or flaws” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction)—thus keeping them psychologically weakened.

Work

Wolf introduces the chapter with a staggering insight: as women entered the workforce in greater numbers, the beauty myth became institutionalized to suppress their upward mobility. She calls it a “third shift”—after paid work and unpaid domestic labor, women now carry the burden of a beauty labor that is expected but never compensated.

“As women demanded access to power, the power structure used the beauty myth materially to undermine women’s advancement.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 27)

Professional women are judged by their looks more than men, and appearance has become a “qualification” for hiring and promotion. Courts have even upheld employment discrimination based on appearance. Wolf likens this to a modern caste system.

This beauty myth translates into real consequences. In the 1980s, when women surged into law, medicine, and business, the diet and cosmetic surgery industries simultaneously exploded. Women, she says, were forced to “buy” their place at the table with their bodies.

Culture

In this chapter, Wolf dissects the media’s role in sustaining beauty standards. She highlights how magazines, advertisements, television, and pornography construct a homogenized image of womanhood. Crucially, she writes:

“The beauty myth is always actually prescribing behavior and not appearance.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 13)

In other words, “beauty” is a cover for obedience. The cultural industries portray women in ways that discourage agency and reward conformity. Even pop culture that pretends to be “liberated” often reproduces the same aesthetic expectations.

Wolf calls this manipulation “beauty pornography,” wherein women are shown as sexually objectified, powerless, and eternally youthful. Women who fail to meet the standard are excluded or punished.

“Beauty pornography… undermines women’s new and vulnerable sense of sexual self-worth.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 34)

She also critiques the way fashion and entertainment reward thin, white, young bodies while marginalizing older women and women of color.

Religion

Perhaps one of Wolf’s most original contributions is in this chapter, where she argues that the beauty myth has become a new religious ideology. In the vacuum left by declining religious orthodoxy, beauty rituals—such as diets, skincare routines, and cosmetic procedures—have taken on moral weight.

“The beauty myth is a new religion, and it functions through rituals, taboos, and punishment.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 86)

The parallels are eerie: fasting becomes dieting, self-flagellation becomes cosmetic surgery, and confession becomes the mirror. Beauty becomes a form of secular salvation, one that promises transcendence through physical perfection but delivers only guilt and perpetual inadequacy.

Wolf also draws attention to how women internalize these standards. They come to see their own bodies as enemies, perpetuating cycles of shame, punishment, and sacrifice.

Sex

In the chapter on sex, Wolf powerfully critiques how the beauty myth undermines female sexuality. She explores the ways pornography, advertising, and even medicine condition women to believe that their sexual desirability is based on physical perfection—not connection, experience, or desire.

“Beauty ideology tells women what is sexy. It is not a response to their real sexual appetites.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 131)

As a result, women often perform sexuality rather than experience it. The myth trains them to seek male approval, repress their own desires, and even endure pain or surgery to become more “sexually desirable.” Female sexuality is narrowed to a single script: youthful, submissive, flawless.

In one particularly searing passage, Wolf highlights how many women lose their sexual agency trying to meet unrealistic ideals shaped by pornography and male fantasy.

She also emphasizes how sexual freedom is often revoked once women “fail” to conform to beauty expectations—such as aging, weight gain, or motherhood.

Hunger

Perhaps the most haunting chapter of the book, “Hunger” explores the epidemic of eating disorders as a political consequence of the beauty myth. Wolf views anorexia, bulimia, and compulsive dieting not merely as individual pathologies, but as collective reactions to a culture that demands thinness as a moral virtue.

“Anorexia is not a personal illness. It is a political one.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 179)

She presents disturbing statistics: At the time of publication, the National Institutes of Health found that 1 to 2% of American women were anorexic—up to 3 million individuals. The death rate for anorexia was 12 times higher than all other causes for girls aged 15 to 24 (The Beauty Myth, Introduction).

Wolf calls this the “cultural conspiracy of thinness,” one in which women are taught that to control their appetite is to control their worth. This control becomes addictive—something she personally witnessed among peers and readers.

This section is perhaps the most devastating in its depiction of how beauty ideals literally starve female potential. A woman preoccupied with food, weight, and body image has little energy left to resist injustice, succeed professionally, or love herself.

Violence

Wolf dedicates this chapter to exploring how beauty standards are enforced not only psychologically, but also physically. From domestic abuse to plastic surgery complications, she argues that women’s bodies are disciplined and punished for failing to meet societal ideals.

“The beauty myth is the ideology that compels women to harm themselves for approval.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 218)

She recounts how women suffer silently through dangerous procedures—silicone implants, chemical peels, starvation diets—while the industries profiting from these harms go unregulated. The violence is often invisible, normalized, and reframed as “empowerment.”

Wolf also touches on sexual harassment, noting how appearance is used as both a cause and excuse for violence against women. If a woman is considered attractive, she is blamed for inviting harassment; if she is not, she is dismissed.

Beyond the Beauty Myth

In the final chapter, Wolf shifts from analysis to advocacy. She urges women to reclaim their bodies, their definitions of beauty, and their right to autonomy.

“It is not ballots or lobbyists or placards that women will need first; it is a new way to see.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 276)

She suggests that women need a collective awakening—one where they deconstruct the ideals they’ve internalized, reject oppressive beauty practices, and forge their own definitions of self-worth. She is not against beauty per se, but against the way it is used to punish, exclude, and commodify.

Her closing lines echo like a manifesto:

“You have the power to take that freedom further still. I hope that you use this book in a whole new way—one that no one but you has thought of yet.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction)

Summary Highlights of The Beauty Myth

Here’s a distilled breakdown of the key themes and lessons from the entire book:

| Chapter | Key Takeaways |

|---|---|

| The Beauty Myth | Beauty is a political ideology, not a biological truth. |

| Work | Beauty standards are used to discriminate in the workplace. |

| Culture | Media perpetuates unattainable beauty ideals that regulate behavior. |

| Religion | Beauty rituals have replaced religious rituals, moralizing appearance. |

| Sex | Women are sexualized through a male gaze, not their own desires. |

| Hunger | Eating disorders are culturally produced forms of control. |

| Violence | Cosmetic and sexual violence enforce beauty norms. |

| Beyond the Myth | Liberation comes through consciousness, critique, and solidarity. |

Critical Analysis of The Beauty Myth

Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth is not just a book—it is a cultural intervention. It entered the public discourse at a time when feminism was being delegitimized, and the backlash against women’s progress was subtly mutating. This section will critically evaluate Wolf’s content, argumentative logic, writing style, authority, and the enduring relevance of her ideas in today’s world.

Evaluation of Content and Evidence

Wolf’s central argument—that beauty standards are a political weapon used to suppress women’s autonomy—is powerful, urgent, and deeply resonant. Her thematic structure lends clarity and momentum to her analysis, each chapter revealing how deeply embedded beauty norms are across societal institutions.

“The ideology of beauty is the last one remaining of the old feminine ideologies that still has the power to control those women whom second wave feminism would have otherwise made relatively uncontrollable.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 16)

This is a bold thesis, and Wolf supports it through a fusion of personal testimony, media critique, historical context, and feminist theory. Her interdisciplinary approach is one of the book’s strengths. She references anthropology, sociology, advertising theory, mythology, economics, and history to support her claims. For example, she draws on evolutionary theory only to dismantle its misuse:

“Beauty is not universal or changeless… Nor is it a function of evolution… Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 12)

However, one of the book’s most contentious elements is its use of statistics, some of which have been widely criticized as inaccurate or exaggerated. Most infamously, Wolf claimed that 150,000 American women die annually from anorexia, a figure disputed by scholars like Christina Hoff Sommers, who noted that the actual number was closer to 100–500 per year.

Similarly, a 2004 study found that “on average, an anorexia statistic in any edition of The Beauty Myth should be divided by eight to get near the real statistic”. These discrepancies, while not discrediting the book’s core arguments, do suggest a tendency toward rhetorical inflation rather than strict empirical rigor.

Yet, Wolf’s central thesis—that beauty is used systemically to distract and disempower women—is not dependent on these statistics alone. The real weight of her argument lies in her observational acuity and ability to connect disparate social trends under a coherent ideological critique.

Logical Structure and Argumentation

Wolf’s book follows a structured, thematic progression, which adds clarity and allows each dimension of the beauty myth to build upon the last. She moves from workplace discrimination to religious symbolism, from hunger to violence, showing how beauty operates not in isolation but as a comprehensive system of control.

Her most compelling conceptual tool is the “Iron Maiden” metaphor:

“The original Iron Maiden was a medieval instrument of torture… The unlucky victim was slowly enclosed inside her… Contemporary culture directs attention to imagery of the Iron Maiden, while censoring real women’s faces and bodies.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 18)

This metaphor is deeply effective: it fuses history, violence, and ideology into one image. Women are not just imprisoned by beauty standards—they are mutilated by them.

That said, critics have noted that Wolf’s arguments sometimes rely too heavily on anecdotal and generalized evidence. While her insights are illuminating, she occasionally makes sweeping claims without concrete sourcing. For instance, assertions about “most women” or “millions of girls” can feel unsubstantiated. This rhetorical style may emotionally engage readers but reduces academic defensibility.

Nonetheless, her argument is logically internally consistent. She lays out a problem, illustrates it across different spheres, connects it to institutional power, and ends with a call to collective resistance. It’s a complete ideological map.

Style and Accessibility

Wolf’s writing style is both passionate and poetic, often blurring the line between polemic and prose. This is not a dry academic text—it is personal, literary, and designed to provoke. Her epigraph, a quote from Virginia Woolf—“It is far more difficult to murder a phantom than a reality”—sets the tone for a book that is as much about consciousness as it is about data.

“Women’s identity must be premised upon our ‘beauty’ so that we will remain vulnerable to outside approval, carrying the vital sensitive organ of self-esteem exposed to the air.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 20)

Wolf’s metaphors—currency, hallucination, religion, the Iron Maiden—are deliberately emotive. They make abstract systems tangible, and for many readers, unforgettable.

Still, her style occasionally drifts into hyperbole or moral absolutism. She paints the beauty myth as an all-encompassing force, which can make the reader feel overwhelmed or skeptical. Critics like Camille Paglia have accused Wolf of lacking nuance, arguing that her analysis disregards individual agency and oversimplifies complex cultural phenomena.

Yet, the accessibility of her style has ensured the book’s enduring popularity. This is a book for both scholars and everyday readers. It’s a feminist primer disguised as a manifesto—and that’s exactly why it worked.

Relevance to Current Issues

Despite being published in 1990, The Beauty Myth remains painfully relevant in 2025. The beauty industry is now a trillion-dollar global machine. Cosmetic surgery, once taboo, is normalized—even celebrated. Influencer culture has replaced fashion magazines but serves the same purpose: to create unattainable ideals. Social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok amplify appearance-based validation.

Wolf predicted this trajectory. In her 2002 update, she observed the increasing sexualization of young girls, the rise of plastic surgery, and the growing normalization of eating disorders. She wrote:

“Even pop culture has responded to women’s concerns… But while The Beauty Myth has definitely empowered many girls and women… there are many ways in which that one step forward has been tempered by various steps back.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction, 2002)

From the Kardashians to GLP-1 weight-loss drugs, the beauty myth has evolved—but not disappeared. As feminist scholar Susan Bordo argued, power doesn’t vanish. It mutates. And Naomi Wolf’s theory remains one of the most prescient roadmaps for understanding that transformation.

Author’s Authority and Expertise

Naomi Wolf’s credentials are impressive. She graduated from Yale, was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, and became one of the youngest feminist public intellectuals in the early 1990s. Her lived experience, combined with her academic training, adds a layer of authenticity to her analysis.

She is also transparent about the personal nature of her project:

“I had the good luck to write a book that connected my own experience to that of women everywhere.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction)

However, her later career has been marred by controversy. She has been criticized for factual inaccuracies, particularly in later works such as Outrages. Some of her public statements have led commentators to question her commitment to evidence-based analysis.

Nonetheless, when it comes to The Beauty Myth, her voice was both timely and necessary. The fact that the book continues to be read, quoted, and taught—decades later—is a testament to her impact. While she may not always meet the standards of peer-reviewed academic rigor, her work resonates where it matters: with real readers, in real life.

🔍 Overall Critical Impression

Despite its flaws in sourcing and its occasional reliance on sweeping rhetoric, The Beauty Myth is an indispensable feminist text. Its contribution is not that it reveals a new oppression, but that it names one that millions of women have felt but never understood. Wolf gave language to a silent pain—a constant background hum of shame, comparison, and inadequacy.

If The Feminine Mystique explained why women felt unfulfilled in the 1950s, The Beauty Myth explained why women felt exhausted and self-critical in the 1990s—and still do today.

Strengths and Weaknesses of The Beauty Myth

In any seminal feminist work, especially one that ignites intense cultural debate and widespread public engagement, a balanced critical evaluation must consider both what the book achieves and where it falls short. The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf is no exception. While the book remains a landmark in feminist literature and media criticism, it is also a text that has drawn fair and harsh critiques for its methodology, tone, and theoretical claims.

✅ Strengths of The Beauty Myth

1. 🔹 Groundbreaking Conceptual Framework

Wolf’s central insight—that beauty is an ideological weapon used to undermine female empowerment—is nothing short of revolutionary. Her framework connects dots that had previously been treated in isolation: advertising, fashion, eating disorders, workplace discrimination, cosmetic surgery, and religious guilt.

“The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men’s institutions and institutional power.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 12)

This conceptual unification of disparate trends into a coherent feminist theory gives the book intellectual heft and enduring relevance. The idea that beauty operates as a modern ideology—as powerful as any religion, law, or myth—is a major theoretical contribution to feminist literature.

2. 🔹 Interdisciplinary Approach

Wolf weaves together literature, history, psychology, sociology, and political theory with a journalist’s attention to detail. She references everything from Virginia Woolf to Charles Darwin, and even advertising studies, giving her narrative a wide-ranging perspective.

This makes The Beauty Myth both intellectually stimulating and broadly accessible—an ideal gateway for readers new to feminist critique but hungry for intellectual depth.

3. 🔹 Cultural Impact and Empowerment

One of the greatest accomplishments of The Beauty Myth lies not in academia but in its popular impact. Wolf’s book was a catalyst for many women re-evaluating their relationship with their bodies, media, and beauty standards.

She writes, with gratitude:

“This book helped me get over my eating disorder,” many women told her. “I’ve stopped hating my crow’s feet.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction)

That’s no small feat. The book gave women language to name their pain, and in doing so, created a path to healing and self-acceptance.

4. 🔹 Timelessness and Prescience

Even though the book was published in 1990, many of its predictions have come true. Today’s rise of Instagram filters, digital body modifications, influencer culture, and cosmetic injectables echo Wolf’s warnings about the escalation and normalization of the beauty myth.

Her identification of beauty pluralism as a false promise—one that masks deeper inequalities—was prophetic:

“So has beauty-myth pluralism taken the day? Not by a long shot.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction, 2002)

5. 🔹 Accessible, Emotional, and Motivational Writing Style

Wolf’s style is neither academic nor dry. It is rhetorically charged, often lyrical, and emotionally resonant. She uses powerful metaphors—like the “Iron Maiden” and “beauty as currency”—to drive home her points in ways that stay with readers long after the book is closed.

This is a book meant to mobilize, not merely inform. It’s a call to arms, a mirror, and a cultural map.

❌ Weaknesses of The Beauty Myth

1. Factual Inaccuracies and Questionable Statistics

This is perhaps the most widely cited criticism of Wolf’s work. Her assertion that 150,000 women die each year from anorexia in the U.S. has been thoroughly debunked.

“Schoemaker calculated that there are about 525 annual deaths from anorexia—286 times less than Wolf’s statistic.” (Wikipedia, citing Eat Disord., 2004)

This has led critics like Christina Hoff Sommers and Camille Paglia to argue that the book undermines itself by failing to adhere to factual rigor. It also risks reinforcing stereotypes of feminism as exaggerative or unscientific.

That said, the emotional truth of the argument—that women’s health is imperiled by beauty standards—remains intact. But the statistical overreach weakens its authority in policy or scholarly contexts.

2. Overgeneralization

Wolf often writes in sweeping terms, making claims about “all women,” “millions of girls,” or “society as a whole” without specifying geography, class, or race.

While she does acknowledge race and cultural difference—especially in the 2002 update—the original text is heavily skewed toward Western, white, middle-class women. Issues specific to Black, Latina, Asian, Indigenous, or trans women are not sufficiently explored.

3. Limited Male Analysis

Although Wolf hints at the emerging male beauty myth, the book gives it only cursory attention. In a time when men are increasingly subject to body image pressures—from six-pack abs to hair restoration—the book feels a bit gender-binary and heteronormative.

She writes:

“As I predicted… a male beauty myth has established itself… hitting suburban dads with a brand-new anxiety.” (The Beauty Myth, Introduction, 2002)

But this acknowledgment comes too late, and too briefly.

4. Lack of Intersectional Depth

Wolf doesn’t fully engage with intersectional feminism—the idea that race, class, sexuality, disability, and other axes of identity intersect with gender to shape oppression. While she nods to this briefly, the book lacks critical depth in these areas.

For example, the beauty myth for a white, affluent woman will differ radically from that experienced by a disabled, queer, Black woman in a working-class context. These distinctions are barely acknowledged, leaving parts of the book feeling outdated in today’s intersectionally aware feminist landscape.

5. Heavy Rhetoric and Polemicism

Wolf’s passionate tone is a strength—but also a risk. Her language can feel alarmist or ideologically rigid, particularly to readers who value nuance and pluralism.

Critics like Camille Paglia have lambasted Wolf’s prose as “overheated and humorless,” arguing that she pathologizes natural human desires like grooming or sexual attraction.

Indeed, not all beauty practices are coercive. For some women, fashion, makeup, and adornment are empowering. Wolf’s argument doesn’t always allow space for agency, play, or ambivalence in relation to beauty.

🔍 Balanced Verdict

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Revolutionary thesis on beauty as ideology | Reliance on debunked statistics |

| Interdisciplinary and poetic style | Lack of intersectional and racial nuance |

| Cultural and emotional resonance | Generalizes across gender/class/race |

| Long-lasting influence and prescience | Can be rhetorically overbearing |

| Accessible to general readers | Limited male and queer perspectives |

Despite its flaws, The Beauty Myth succeeds as a foundational feminist analysis that has aged surprisingly well. It may not be flawless—but it is necessary.

Reception, Criticism, and Influence of The Beauty Myth

Since its release in 1990, Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth has sparked praise, backlash, academic critique, and popular reflection. As both a cultural artifact and intellectual provocation, the book carved out a significant space in feminist literature and beyond. Its reception offers crucial insight into how societies grapple with feminist theories that strike at the heart of appearance, autonomy, and capitalism.

Immediate Reception: A Publishing Sensation

Upon release, The Beauty Myth received wide attention from both feminist communities and mainstream media. It was lauded by Gloria Steinem, embraced by college campuses, and praised for giving “voice to a generation.” The New York Times called it “provocative,” while The Guardian noted it “brilliantly exposed the tyranny of beauty culture.”

Wolf quickly became a media figure. Her visibility as an articulate, attractive, and young feminist public intellectual was, ironically, part of what made the book popular—though she herself warned against the very media mechanisms that celebrated her. In interviews, she often emphasized the paradox: “My looks helped me get noticed while my book critiqued the system that made those looks central.”

She was part of the so-called “Third Wave“ of feminism, alongside writers like Rebecca Walker and bell hooks, who brought new voice and vitality to feminist conversation in the early ’90s.

Academic and Feminist Criticism

While the book was celebrated in popular media, many academics and feminist scholars were more critical. The most frequent criticisms include:

1. Statistical Inaccuracy and Rhetorical Overreach

As noted earlier, Wolf’s claim that 150,000 women die each year of anorexia was widely debunked. Scholars like Christina Hoff Sommers, in her book Who Stole Feminism?, argued that such misrepresentations harmed the credibility of feminism:

“Wolf’s claim about anorexia deaths is not just false—it’s egregiously, irresponsibly false. It weakens the cause it tries to serve.” – Christina Hoff Sommers

The academic journal Eating Disorders published studies correcting her figures, noting that even generous estimates place anorexia-related deaths in the hundreds, not hundreds of thousands.

2. Overgeneralization and Lack of Empirical Foundation

Critics such as Camille Paglia and Katie Roiphe argued that Wolf imposed a monolithic feminist lens on what they believed to be diverse female experiences. Paglia, always a contrarian, wrote in Vamps & Tramps:

“Wolf’s The Beauty Myth is a fatwa against pleasure… a doctrinaire diatribe that reduces women to helpless victims of male patriarchy.”

Roiphe added that Wolf infantilized women by portraying them as passive sufferers, ignoring their agency in choosing beauty practices.

Enduring Feminist Influence

Despite academic critiques, The Beauty Myth remains a cornerstone of feminist consciousness. It is still taught in women’s studies courses, frequently cited in cultural critiques, and referenced in works on media representation, body image, and beauty capitalism.

Writers like Roxane Gay, Lindy West, Jessica Valenti, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie have continued Wolf’s legacy by interrogating how media images shape gendered expectations. While many of them bring a more intersectional lens, the intellectual lineage is clear.

For instance, Roxane Gay’s Hunger reflects Wolf’s influence when Gay writes:

“This hunger—this need to be small, desirable, quiet—was created by a culture that feared my largeness.”

Furthermore, feminist podcasts, TikTok activists, and Gen Z influencers frequently return to the core ideas in The Beauty Myth—especially when critiquing beauty filters, fatphobia, Botox culture, and Instagram aesthetic pressures.

Cultural Influence Beyond Feminism

The impact of The Beauty Myth reached well beyond feminist circles. It influenced:

- Advertising criticism (e.g., Dove’s “Real Beauty” campaign)

- Body positivity movements

- Critical theory in gender studies

- Documentaries like Miss Representation and Killing Us Softly

- Beauty journalism and self-help literature

In 2016, the BBC listed The Beauty Myth as one of the “100 most influential books by women.” It is often cited in the same breath as The Feminine Mystique, The Second Sex, and Gender Trouble—a testament to its lasting cultural weight.

International Reception

The book was translated into more than 14 languages, receiving global attention. In countries like India, Japan, South Africa, and Brazil—where Westernized beauty standards were spreading through advertising—readers found new tools to critique emerging forms of aesthetic colonization.

However, cultural critics from the Global South pointed out that Wolf’s analysis was deeply Western-centric. Issues like skin-lightening, colonial hangovers, traditional adornment, and caste-based beauty standards were only peripherally acknowledged. While the beauty myth exists globally, its expressions vary—and Wolf’s book sometimes assumes a universalism that doesn’t hold up.

Naomi Wolf’s Later Career and Controversy

Wolf continued publishing feminist books—Fire With Fire, Misconceptions, Promiscuities—and became a prominent commentator on political and gender issues. However, her reputation took a downturn after a 2019 BBC interview where she was publicly corrected for a fundamental misreading of legal terminology in her book Outrages.

More recently, she faced criticism for controversial stances on COVID-19, vaccine misinformation, and her alignment with right-wing conspiracy narratives. These developments have prompted some to re-evaluate her credibility, but most scholars still separate her early feminist contributions—especially The Beauty Myth—from her later political trajectory.

Summary: Cultural Footprint of The Beauty Myth

| Aspect | Impact |

|---|---|

| Feminist Reception | Praised by Gloria Steinem; taught widely in academia |

| Main Criticisms | Statistical inaccuracy, overgeneralization, limited intersectionality |

| Cultural Impact | Helped launch the beauty politics movement; inspired body positivity activism |

| International Reach | Global readership, though sometimes critiqued as Western-centric |

| Legacy | Canonical feminist text, still cited, taught, and debated in 2025 |

Quotations from The Beauty Myth

Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth is rich with rhetorical firepower, sharp metaphors, and striking observations that have become cultural shorthand in feminist and body image discourse. Below is a curated list of the most powerful, memorable, and SEO-rich quotations from the book—suitable for citation, academic reference, social media, or SEO-optimized blogs on feminist theory and the politics of beauty.

Foundational Quotes: Defining the Beauty Myth

“The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men’s institutions and institutional power.”

“Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard.”

“The more legal and material hindrances women have broken through, the more strictly and heavily and cruelly images of female beauty have come to weigh upon us.”

“The beauty myth is always actually prescribing behavior and not appearance.”

“An ideology that makes women feel they must adhere to unrealistic beauty standards in order to be accepted or successful is not about beauty. It is about obedience.”

On Work and Power

“As women have advanced in the workforce, the beauty myth has become stronger—because it is needed to counterbalance women’s real power.”

“No woman wins under the myth. Each woman must contemplate the use of time, energy, and money necessary to maintain the illusion.”

“The workplace may hire a woman, but will penalize her for not appearing sexually appealing while accusing her of being manipulative if she does.”

On Media and Culture

“Beauty pornography is not about sex, it is about power. It is designed to make women feel inferior and men feel dominant.”

“Images of female beauty are political. They are used to keep women down, not lift them up.”

“Advertising doesn’t sell beauty—it sells anxiety. And the products offer only the illusion of relief.”

On Religion and the Morality of Appearance

“The beauty myth has replaced traditional religion for many women. Rituals of dieting, grooming, and self-punishment have taken on spiritual urgency.”

(The Beauty Myth, p. 86)“In a secular society, the ideology of beauty functions as a religion—a sacred standard by which women are judged and judge themselves.”

(The Beauty Myth, Religion chapter)“Virtue and vice have become visible in flesh, rather than in action.”

(The Beauty Myth, Religion chapter)

On Sex and Desire

“The myth tells women how to be sexually desirable to men, but not how to be sexually fulfilled themselves.”

(The Beauty Myth, Sex chapter)“Pornography and advertising often look alike. Both erase female agency, and both script desire from the outside.”

(The Beauty Myth, p. 131)“When a woman looks in the mirror, she sees not herself but an aesthetic ideal she must continually fail to achieve.”

(The Beauty Myth, p. 120)

On Hunger and Eating Disorders

“Dieting is the most potent political sedative in women’s history. A quietly mad population is a tractable one.”

“Anorexia is a political disease. Women literally starve themselves to meet a political standard of beauty.”

“A culture fixated on female thinness is not an obsession about female beauty but an obsession about female obedience.”

On Violence and Cosmetic Harm

“The most extreme expressions of the beauty myth—plastic surgery, eating disorders, cosmetic poisoning—are rarely seen as violence because they’re internalized.”

“When beauty becomes a weapon, women harm themselves to be loved.”

On Liberation and Consciousness

“It is not ballots or lobbyists or placards that women will need first; it is a new way to see.”

“The real liberation begins when we stop defining ourselves by how we look and start defining ourselves by what we do.”

“The struggle for women’s freedom is not about escaping biology. It is about escaping ideology.”

| Topic | Quote |

|---|---|

| Definition | “Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard.” |

| Work | “No woman wins under the myth.” |

| Culture | “Advertising sells anxiety.” |

| Religion | “Virtue and vice have become visible in flesh.” |

| Sex | “The myth tells women how to be desirable, not fulfilled.” |

| Hunger | “Dieting is the most potent political sedative.” |

| Liberation | “It is a new way to see.” |

Comparison with Similar Works

In the broader ecosystem of feminist literature, The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf holds a distinct but interconnected place. It shares thematic DNA with iconic feminist works such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Susan Faludi’s Backlash, bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman, and Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex—yet its focus, tone, and audience differ in critical ways.

This section compares The Beauty Myth with these major feminist works to contextualize its unique contributions and ideological overlaps.

1. Naomi Wolf vs. Betty Friedan (The Feminine Mystique)

Similarities

- Both texts are generational manifestos that shook the public consciousness and redefined gender discussions.

- Friedan’s “problem that has no name” (the existential emptiness of suburban housewives) parallels Wolf’s “beauty myth” (a silent obsession with appearance and self-surveillance).

- Each book identifies invisible psychological burdens as byproducts of women’s material progress. Friedan writes about postwar domestic ennui; Wolf writes about aesthetic anxiety in the era of workplace participation.

Friedan: “Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds… she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’”

Wolf: “The more legal and material hindrances women have broken through, the more strictly… images of female beauty have come to weigh upon us.” (The Beauty Myth, p. 10)

Differences

- Friedan’s work is deeply rooted in the 1950s-60s suburban context and targets mainly white, middle-class housewives.

- Wolf’s book, while still class-limited, addresses 1990s professional women—and the backlash they face under new aesthetic demands.

- Friedan focused on domestic oppression; Wolf on aesthetic oppression. The domestic “ideal” housewife of Friedan’s day morphed into the hyper-sexualized, hyper-productive, eternally youthful woman that Wolf describes.

2. Naomi Wolf vs. Susan Faludi (Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women)

Similarities

- Both books were published in 1991, marking a crucial moment in third-wave feminism.

- Each addresses how media, pop psychology, and institutions conspire to contain women’s liberation.

- They describe different aspects of the same social regression: Faludi explores the political/media backlash; Wolf analyzes beauty as a covert enforcement tool.

Faludi: “The backlash is not a conspiracy… but a cultural phenomenon, a reaction.”

Wolf: “The beauty myth is not about women… It is about institutional power.”

Differences

- Faludi is more data-driven, with journalistic investigation into government policies, news coverage, and economic trends.

- Wolf’s tone is more poetic, metaphorical, and subjective. She doesn’t just report on facts—she diagnoses cultural consciousness.

Together, these two books act as a double lens: Faludi shows you the system’s gears; Wolf shows you its psychological effects.

3. Naomi Wolf vs. Simone de Beauvoir (The Second Sex)

Similarities

- Both theorize womanhood as a social construction, not a biological destiny.

- Beauvoir’s assertion—“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”—resonates with Wolf’s claim that beauty is a cultural fiction designed to maintain control.

- Both explore the symbolic and lived oppression of female bodies, although Wolf focuses more narrowly on beauty and media.

Beauvoir: “To be feminine is to show oneself as weak, futile, docile.”

Wolf: “A woman’s appearance is not just her appearance. It is a statement of her acceptability, her worth, her right to occupy space.”

Differences

- The Second Sex is a philosophical treatise, grounded in existentialism and ontology.

- The Beauty Myth is more pop-feminist—less abstract, more digestible, targeted toward a broader audience.

- Beauvoir writes as a theorist; Wolf writes as an activist.

4. Naomi Wolf vs. bell hooks (Ain’t I a Woman and Feminism Is for Everybody)

Similarities

- Both are critical of how feminism has excluded marginalized voices—though hooks engages this issue more directly.

- Both critique how white patriarchy uses different tools—whether it’s beauty or colonial violence—to suppress autonomy.

hooks: “Feminism is the struggle to end sexist oppression.”

Wolf: “The beauty myth tells women what they should look like so they’ll be easy to control.”

Differences

- hooks is more intersectional. She integrates race, class, and colonial history into her feminist lens.

- Wolf’s original edition is less inclusive, focusing on largely white, cisgender, heterosexual women.

- bell hooks emphasizes community and love as tools for liberation; Wolf emphasizes consciousness and critique.

5. Naomi Wolf vs. Joan Jacobs Brumberg (The Body Project) and Susan Bordo (Unbearable Weight)

Scholarly Comparisons

- Brumberg’s The Body Project examines girls’ diaries from the 1800s to the 1990s to show how the female body has become central to identity.

- Bordo’s Unbearable Weight (1993) is often considered a more rigorous academic version of The Beauty Myth, analyzing body image, dieting, and control through post-structural feminist theory.

Bordo: “The female body is the site of cultural inscription.”

Wolf: “Dieting is a political sedative. A quietly mad population is a tractable one.”

While Bordo is more grounded in Foucault and theory, Wolf’s influence lies in accessibility and cultural impact.

Summary Comparison Table

| Author | Work | Focus | Tone/Method | Unique Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naomi Wolf | The Beauty Myth | Beauty as ideological control | Poetic, political | Introduced beauty critique to mass feminism |

| Betty Friedan | The Feminine Mystique | Domesticity and unfulfillment | Sociological, anecdotal | Sparked second-wave feminism |

| Susan Faludi | Backlash | Media backlash against feminism | Investigative, journalistic | Showed systemic rollback of women’s rights |

| Simone de Beauvoir | The Second Sex | Existential feminism | Philosophical | Laid groundwork for feminist theory |

| bell hooks | Ain’t I a Woman | Intersectionality, race and gender | Political, personal | Centered Black women in feminist analysis |

| Susan Bordo | Unbearable Weight | Body image and power | Academic, theoretical | Foucaultian feminist body theory |

While The Beauty Myth may not be as theoretically rich as The Second Sex or as intersectional as Ain’t I a Woman, it fills a critical gap in feminist thought by naming and politicizing beauty. It opened the door for deeper analysis of how aesthetics, capitalism, and patriarchy intersect to oppress women. In doing so, Naomi Wolf created a gateway for countless readers to enter feminist discourse—and challenged an entire generation to question the mirror.

About the Author: Naomi Wolf

Naomi Wolf is an American author, journalist, and feminist theorist best known for her groundbreaking 1990 book The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. Born in San Francisco in 1962, Wolf grew up in a progressive, intellectual environment—her mother was an anthropologist and her father a poet. She studied at Yale University, graduating with honors in English Literature, and later became a Rhodes Scholar at New College, Oxford.

Her intellectual and literary career was launched into public consciousness with The Beauty Myth, which became an international bestseller and was named one of The New York Times’ Notable Books of the Year. The book helped define the early 1990s wave of feminist thought and inspired a new generation of women to critically examine the role of appearance, media, and cultural conditioning.

Wolf followed up with other influential titles including:

- Fire with Fire (1993), which called for a reclaiming of power feminism;

- Misconceptions (2001), an exploration of pregnancy and motherhood;

- The End of America (2007), a political analysis warning of democratic erosion;

- and Outrages (2019), her controversial book on censorship and sexuality in Victorian Britain.

Over the years, Naomi Wolf has written for major outlets including The Guardian, The New Republic, The Huffington Post, and The New York Times. Her career has straddled multiple genres: political critique, personal narrative, historical revisionism, and media analysis.

Contributions to Feminism and Public Discourse

Wolf’s early work positioned her as a key figure in Third-Wave Feminism, a movement known for expanding feminist theory beyond legal rights to issues of sexuality, body politics, race, and representation. Her notion of beauty as a modern ideology—akin to religious or legal systems of control—reframed how women understood personal grooming, dieting, and self-image.

She wrote, in the introduction to The Beauty Myth:

“A cultural fixation on female thinness is not an obsession about female beauty but an obsession about female obedience.”

Though not without controversy, her early feminist work has left a lasting legacy in academia, women’s studies programs, and popular feminist media.

Controversies and Later Years

In more recent years, Wolf’s reputation has been marked by controversy. Her 2019 book Outrages was publicly discredited during a BBC interview when a fundamental historical error was pointed out live on air. This led to widespread media coverage and the publisher delaying its U.S. release.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Wolf drew further criticism for spreading vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories via social media, leading platforms like Twitter (now X) to temporarily suspend her account. These positions distanced her from many feminist and academic communities, raising debates about the line between dissent and misinformation.

Despite these later developments, her earlier contributions—particularly The Beauty Myth—continue to be studied, cited, and defended as formative feminist work.

🔍 Legacy

Love her or critique her, Naomi Wolf remains one of the most influential and provocative voices in American feminist writing. Her work in the 1990s helped millions of women question inherited norms about their bodies and public roles, and brought the conversation about beauty politics to the center of popular feminist dialogue.

Today, The Beauty Myth is considered a modern feminist classic, and Wolf’s early voice still echoes in debates about the body, gender, power, and media.

Conclusion: Final Reflections on The Beauty Myth

After nearly 35 years since its first publication, Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth remains an urgent and provocative work. It is not merely a feminist critique of cultural beauty standards—it is a searing political manifesto, a mirror held up to society, and for many, an introduction to feminist consciousness itself.

Revisiting the Thesis

At its core, Wolf’s central claim—that beauty standards are a political tool to regulate women—has only grown in relevance. The 1990s beauty myths she critiqued have morphed, not disappeared. Today’s version may wear the mask of “self-care” or “empowerment,” but it continues to extract time, labor, money, and emotional energy from women, keeping them distracted, anxious, and commodified.

“The beauty myth tells a story: It claims to be about individuality and aesthetic pleasure, but it is really about social control.”

(The Beauty Myth, p. 10)

Her thesis resonates in a world obsessed with Instagram filters, AI-enhanced body images, and ‘glow-up’ culture. Whether it’s the explosion of Botox clinics or the commodification of the “hot girl walk,” the beauty myth has adapted to every era—just as Wolf warned.

Who Should Read The Beauty Myth?

This book is for:

- Women of all ages confronting appearance-based anxiety.

- Students of feminist theory, media studies, or cultural criticism.

- Activists pushing back against the commodification of bodies.

- Anyone tired of the exhausting, endless pursuit of the “ideal woman.”

But readers should supplement it with:

- Feminism Is for Everybody by bell hooks (for intersectionality)

- Unbearable Weight by Susan Bordo (for academic depth)

- Hood Feminism by Mikki Kendall (for race and class awareness)

Together, these texts offer a holistic understanding of how gender, power, and beauty intersect.

Final Thoughts: The Beauty Myth Today

In 2025, the beauty myth is more digitized, more profitable, and more global than ever before. But it’s also more visible. Thanks to thinkers like Naomi Wolf, millions now question the systems that once felt natural. We no longer assume beauty is a matter of taste or biology. We ask: Whose standard? Who profits? At what cost?

“There is no liberation without seeing what enslaves you.”

(The Beauty Myth, Conclusion)

Wolf’s lasting contribution is not a perfect dataset or a peer-reviewed theory. It is her gift of vision—a lens through which to understand the pain and performance of womanhood in a culture built on appearances. And once you’ve seen through the beauty myth, it becomes harder to play along.