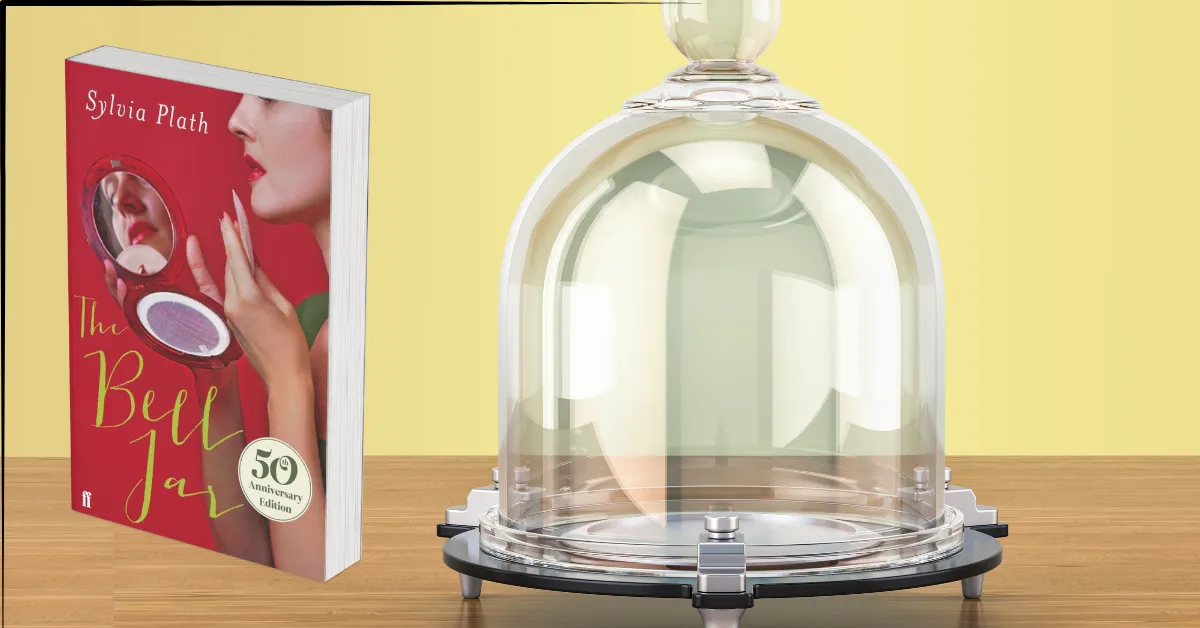

When a novel continues to resonate decades after its publication, it is often because it speaks a language far deeper than the era it was born into. The Bell Jar, first published in 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas, is one such work.

Written by Sylvia Plath, a poet of startling precision and intensity, the novel captures the fragile intersection of identity, ambition, and mental illness in a society reluctant to acknowledge such struggles.

The semi-autobiographical narrative mirrors Plath’s own life, particularly her time as a young woman navigating the pressures of the 1950s, when societal expectations for women were rigid and unforgiving.

This was the only novel Plath published in her lifetime, yet its influence has been monumental — taught in literature courses, examined in feminist theory, and dissected in mental health discussions.

In the UK, where it was first released, The Bell Jar quickly gained attention for its unflinching portrayal of depression and its nuanced critique of gender roles. It was only in 1971, eight years after Plath’s death, that the novel appeared in the United States, where it would become a touchstone for generations seeking to understand the inner voice of a young woman in crisis.

“Wherever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

(Plath, The Bell Jar, Ch. 15)

The image of the bell jar is perhaps one of literature’s most haunting metaphors — a transparent but suffocating dome that traps the self, magnifying isolation and despair. The narrative follows Esther Greenwood, an ambitious and academically gifted college student whose life appears enviable from the outside.

Yet beneath her achievements lies a growing disconnect between her inner reality and the life she feels compelled to perform.

From a literary standpoint, The Bell Jar sits at the crossroads of Bildungsroman (coming-of-age novel), psychological fiction, and feminist literature. It is as much about the structure of a mind unraveling as it is about the cultural framework pressing down upon it.

In terms of influence, the book stands alongside other works of confessional fiction such as J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, yet retains a uniquely sharp, intimate, and modern voice.

My reading of The Bell Jar confirms why it remains indispensable in literary, cultural, and psychological discourse:

- It captures the textures of depression in a way that clinical descriptions cannot.

- It critiques the gendered limitations of its time without sacrificing narrative intimacy.

- It embeds poetic sensibility into prose, making even despair articulate.

In this article, I will move from a full background study to a comprehensive plot summary, followed by in-depth character analysis, an exploration of themes and symbolism, and a critical evaluation that situates the book in contemporary relevance. Along the way, I will use direct passages from the novel and insights from literary criticism to ensure this is a resource so complete that readers will not need to refer back to the book for clarity.

Table of Contents

1. Background

When Sylvia Plath wrote The Bell Jar in the early 1960s, she was distilling a decade of lived experience into fiction. Born in 1932 in Boston, Massachusetts, Plath was a gifted student and poet from an early age, publishing her first poem at eight.

She attended Smith College on scholarship and, in 1953, won a guest editorship at Mademoiselle magazine in New York — an opportunity that inspired much of the novel’s first half.

However, the glittering surface of her life masked an inner turbulence. That same summer, Plath suffered a breakdown and attempted suicide — a pivotal life event mirrored in Esther Greenwood’s trajectory. After months in psychiatric care, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), she returned to college and later earned a Fulbright to Cambridge, where she met and married poet Ted Hughes.

Culturally, the novel sits at the end of an era — the conservative 1950s, when women were expected to marry young, maintain a pristine home, and quietly support their husbands’ careers. As critic Linda Wagner-Martin observes, The Bell Jar “emerges from a moment when feminism’s second wave had yet to crest, making its commentary on gender roles all the more startling” (Wagner-Martin, Sylvia Plath: A Biography).

First published in London in January 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas, the book received modest attention in Britain. In the United States, however, publication was delayed until 1971 due to its autobiographical nature and its potential impact on Plath’s family. By then, Plath’s tragic suicide — just a month after the UK release — had already cast the book in a darker, almost mythic light.

Its semi-autobiographical nature has often led readers to conflate Esther’s voice with Plath’s own, a comparison both illuminating and dangerous. While many incidents in the novel parallel Plath’s life, the narrative also functions as a work of fiction shaped by structure, symbolism, and character arcs.

In short, The Bell Jar emerges from the collision of a brilliant mind, a restrictive culture, and a period of personal crisis — a combination that produced one of the most enduring portraits of mental illness in literature.

2. Summary of the Book

Plot Overview

The story begins in the summer of 1953, during the height of the Rosenberg executions — an event that immediately sets a tone of unease. Esther Greenwood, a bright, ambitious nineteen-year-old from Massachusetts, has won a month-long guest editorship at Ladies’ Day magazine in New York City. The opportunity is glamorous on paper — free hotel, designer clothes, celebrity parties — but Esther feels strangely disconnected from it all:

“I was supposed to be having the time of my life. I was supposed to be the envy of thousands of other college girls just like me all over America… and here I was, sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

From the start, her internal state clashes with external expectations. While other girls immerse themselves in fashion shows and society luncheons, Esther drifts between boredom and anxiety. She begins to question her future — should she marry her long-term boyfriend Buddy Willard, or pursue a literary career? Her ambivalence deepens when she learns Buddy, once her model of integrity, has been unfaithful and harbors a hypocritical view of gender roles.

After returning home to Massachusetts, Esther receives devastating news: she has been rejected from a prestigious summer writing program. This rejection triggers a rapid mental decline. She becomes increasingly isolated, insomnia sets in, and her ability to perform simple daily tasks disintegrates. Even reading — once her refuge — feels impossible.

Her mother suggests psychiatric treatment, leading to her first encounter with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The procedure, performed by an indifferent doctor, is traumatic rather than therapeutic:

“I wondered what terrible thing it was that I had done.”

Esther’s depression deepens into suicidal ideation. In a carefully planned attempt, she crawls into the crawlspace beneath her house and overdoses on sleeping pills. She is found days later, barely alive.

The second half of the novel follows her recovery in a series of mental institutions. She comes under the care of Dr. Nolan, a compassionate female psychiatrist who replaces the coldness of earlier medical figures with genuine empathy. Under Dr. Nolan’s guidance, Esther undergoes a more humane course of ECT, which gradually helps lift her mental fog.

During this period, she witnesses the varied fates of other women in treatment — from Joan Gilling, a fellow patient and one-time acquaintance, whose struggles mirror her own, to patients who never escape the cycle of institutionalization. Joan’s eventual suicide is a chilling reminder of how fragile recovery can be.

Esther also negotiates her own relationship to sexuality and autonomy. In one of the most discussed scenes, she decides to lose her virginity — not as a romantic gesture, but as a deliberate act of self-determination. This choice results in a hemorrhage, forcing her to seek emergency medical help, a symbolic reminder of the messy realities beneath idealized notions of womanhood.

As the novel closes, Esther prepares for an interview with the hospital board that will decide if she can be released. She steps “into the room” with uncertainty — the ending is deliberately ambiguous, leaving readers unsure whether her recovery will be lasting or temporary.

Setting

The setting of The Bell Jar operates on two intertwined levels: the physical landscapes Esther inhabits and the psychological terrain that mirrors her internal crisis.

1. Geographical Setting

The novel shifts between New York City and suburban Massachusetts, two environments that sharply contrast in energy and symbolism.

- New York City is presented not as the vibrant center of possibility it appears to others, but as a space of alienation for Esther. The glamour of the city — fashion shows, banquets, rooftop parties — becomes suffocating. The noise, constant social obligations, and competitive undercurrent only amplify her feelings of detachment.

- Massachusetts, her hometown, should offer comfort, but instead it feels stagnant and restrictive. Her return home after the failed writing program application signals a turning point — the slower pace and social expectations become an emotional trap, exacerbating her depression.

2. Time Period

The story is set in the early 1950s, a post-war America defined by rigid gender roles, the idealization of domesticity, and a pervasive mistrust of deviation from the norm. This is crucial to the novel’s thematic weight — Esther’s ambitions as a writer and resistance to the “marry and settle down” model put her in direct conflict with societal norms. This tension becomes one of the driving forces behind her breakdown.

3. Psychological Landscape

The most enduring “setting” of the book is the metaphorical bell jar itself — the glass dome under which Esther feels trapped:

“Wherever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

The bell jar functions as a metaphor for depression, encapsulating a world where sound is muted, air is stale, and escape feels impossible. It is not bound to a location but follows her everywhere, illustrating that her confinement is internal as much as external.

4. Symbolic Spaces

- The Hospital: A microcosm of the broader mental health system of the era, ranging from cold, punitive institutions to more progressive, humane facilities under Dr. Nolan.

- The Crawlspace: The dark, enclosed area where Esther attempts suicide becomes a chilling physical manifestation of her psychological retreat from the world.

- The Fashion Magazine Office: Represents the façade of female empowerment during the 1950s, masking the limitations placed on women’s ambitions.

3. Analysis

3.1. Characters

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar thrives on its deeply human characters — each drawn with enough specificity to feel real, yet symbolic enough to embody broader cultural and psychological themes.

1. Esther Greenwood

The protagonist and narrator, Esther, is a bright, ambitious college student whose literary talent wins her a coveted internship at a New York fashion magazine. At first glance, she appears to be living the dream of many young women of the 1950s. But beneath the surface is a growing sense of alienation, exhaustion, and existential dislocation.

Her character arc traces a descent into severe depression, marked by withdrawal, suicidal thoughts, and eventual psychiatric hospitalization. What makes Esther compelling is the raw honesty of her interior monologue — she often narrates her disconnection with a disarming matter-of-factness:

“I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.”

Esther is not merely a victim of mental illness; she is also a perceptive observer of the societal hypocrisy and gender constraints that contribute to her breakdown. Her resistance to conform — refusing to marry early, doubting motherhood as destiny — positions her as a proto-feminist figure.

2. Buddy Willard

Buddy is Esther’s on-and-off boyfriend, a medical student who represents the patriarchal ideal of the respectable, successful husband. Outwardly charming, Buddy harbors a smug condescension toward women’s ambitions. His belief that poetry is “a piece of dust” compared to medicine symbolizes the cultural devaluation of women’s creative aspirations.

Buddy’s hypocrisy — preaching purity while engaging in a casual sexual relationship — deepens Esther’s disillusionment with traditional romantic expectations.

3. Doreen

A fellow intern in New York, Doreen is rebellious, witty, and dismissive of the conservative femininity that others try to embody. While she is not a role model for Esther, Doreen’s unapologetic independence forces Esther to confront her own desire for freedom versus her fear of nonconformity.

4. Joan Gilling

Joan is a fellow patient in the mental hospital and serves as a mirror for Esther — they share academic excellence, similar social circles, and even romantic connections to Buddy. Joan’s eventual suicide is a haunting reminder of how fragile recovery can be, underscoring that survival is neither guaranteed nor linear.

5. Dr. Nolan

Dr. Nolan is one of the few positive authority figures in Esther’s journey. A compassionate psychiatrist, she introduces Esther to humane therapeutic approaches, including modern ECT administered in a controlled, supportive environment. Dr. Nolan represents hope and the possibility of reconnection to life.

6. Peripheral Characters

- Mrs. Greenwood: Esther’s mother embodies the social pressure to “get better” quickly and quietly, reflecting a generational discomfort with openly discussing mental illness.

- Jay Cee: Esther’s female editor in New York is intelligent, professional, and encouraging — but still operates within a male-dominated environment that limits her influence.

- Marco: A violent encounter with Marco during a party night out reinforces the dangers and aggressions women face in social spaces.

Plath’s characters operate on two levels — as fully formed individuals and as archetypes of mid-century gender politics, societal roles, and mental health attitudes. The interplay between these dimensions makes The Bell Jar more than a personal narrative; it becomes a cultural study in human form.

3.2. Writing Style and Structure

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar stands out as much for how it is written as for what it conveys. The novel’s stylistic and structural choices immerse readers in Esther Greenwood’s psyche, making the reading experience both intimate and unsettling.

Narrative Perspective

The story is told entirely in first-person past tense, with Esther narrating events after they have occurred. This creates a reflective, confessional tone, but with an undercurrent of emotional distance that mirrors her dissociation during depressive episodes. The use of hindsight allows for sharp, ironic commentary on her younger self’s perceptions:

“I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart: I am, I am, I am.”

Language and Tone

Plath’s prose oscillates between lyrical beauty and clinical bluntness, reflecting the instability of Esther’s mental state.

- In moments of alienation, the language turns plain and detached, bordering on report-like.

- During moments of sensory or emotional intensity, it blooms into metaphor and simile — most famously, the bell jar as a metaphor for mental illness:

“Wherever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

This blend of poetic flourish and stark reality makes the narrative deeply immersive.

Pacing

The novel’s pacing mirrors Esther’s mental health trajectory.

- The first half moves at a quicker, event-driven rhythm, chronicling her New York internship and early post-internship summer.

- The second half slows, becoming more fragmented and dreamlike as Esther’s depression deepens.

This structural shift subtly reinforces the suffocating slowdown of clinical depression.

Symbolism

Plath’s metaphors and symbols work on multiple levels:

- The Bell Jar: The most prominent metaphor, representing the suffocating isolation of mental illness.

- The Fig Tree: A vivid image from Esther’s imagination, symbolizing the paralyzing fear of making life choices:

“I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose.”

- Roses, mirrors, and blood imagery: Recur throughout, reinforcing themes of femininity, fragility, and the physical reality of existence.

Structure

The novel is structured chronologically but is punctuated by flashbacks and introspective digressions that blur time. This fluidity captures the way memory and present experience intermingle, especially during periods of psychological crisis.

Literary Devices

- Juxtaposition: Glamorous city life vs. the emptiness Esther feels.

- Irony: The contrast between societal expectations and Esther’s private turmoil.

- Imagery: Often visceral, as in her descriptions of food, illness, and decay.

- Repetition: Certain phrases (“I am, I am, I am”) serve as anchors, intensifying their emotional weight.

Plath’s writing style is intensely personal yet universally resonant, which is why The Bell Jar has maintained both literary acclaim and popular relevance for decades. Its structure ensures readers don’t just witness Esther’s experience — they live it alongside her.

3.3. Themes and Symbolism

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar is not simply a coming-of-age story — it’s a multi-layered exploration of identity, mental illness, and societal expectation. Through its symbols and recurring motifs, the novel offers both a deeply personal and universally resonant narrative.

1. Mental Illness and Isolation

At the heart of The Bell Jar is a candid depiction of depression, grounded in Plath’s own lived experience. Esther’s feeling of being trapped under an invisible barrier — “the bell jar” — becomes the central metaphor for psychological suffocation:

“Wherever I sat… I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

The novel was groundbreaking for the early 1960s, when mental health was cloaked in stigma, making this portrayal both radical and empathetic.

2. The Pressure of Gender Roles

Esther navigates the competing demands of mid-century American womanhood — marriage, career, sexuality — with a growing awareness of their limitations.

- The New York internship dangles the promise of professional fulfillment but comes packaged with superficial glamour and male gatekeeping.

- The marriage expectation looms as a loss of freedom, not a gain:

“The last thing I wanted was infinite security and to be the place an arrow shoots off from. I wanted change and excitement and to shoot off in all directions myself.”

3. Identity and Self-Determination

The fig tree metaphor encapsulates Esther’s paralysis in the face of life choices. Each fig — marriage, career, travel, art — is appealing, but she fears that picking one means losing the others:

“I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind.”

This theme still resonates today in an age of limitless (and often overwhelming) options.

4. Death and Rebirth

The novel does not shy away from suicidal ideation and attempts, portraying them with unflinching detail. Yet, recovery is possible — if tenuous. The end, where the bell jar is “lifted,” hints at rebirth, but the shadow of relapse lingers:

“How did I know that someday — at college, in Europe, somewhere, anywhere — the bell jar, with its stifling distortions, wouldn’t descend again?”

5. The Bell Jar as a Symbol

The title object functions as:

- A representation of mental illness: trapping and distorting reality.

- A feminist metaphor: the glass barrier between women and male-dominated spheres.

- A universal condition: many readers identify with feeling sealed off from life.

6. Nature and the Physical World

References to the sea, flowers, blood, and seasons serve as contrasts to Esther’s inner stagnation. These symbols remind readers of the life cycles continuing outside her mental confinement.

7. Authenticity vs. Performance

Esther’s interactions are often layered with an awareness of performing for societal acceptance — a theme as relevant in the social media age as it was in the 1950s.

By embedding these themes in potent, often unsettling imagery, Plath ensures that The Bell Jar functions on multiple interpretive levels — as both a deeply personal narrative and a cultural critique.

Here’s Section 3.4: Genre-Specific Elements for The Bell Jar.

3.4. Genre-Specific Elements

1. Place in Literary Tradition

The Bell Jar occupies a unique position in 20th-century literature — blending bildungsroman (coming-of-age novel), feminist literature, and psychological fiction. While it parallels classic narratives of young women’s self-discovery like Jane Eyre and The Awakening, its raw depiction of mental illness situates it firmly in the confessional tradition, a style that Plath herself helped define.

2. Dialogue Quality

The dialogue alternates between sharp, witty exchanges and flat, fragmented conversations that mirror Esther’s psychological state.

- In New York scenes, dialogue is brisk and laced with social critique, such as her sardonic exchanges with Doreen.

- In moments of depression, conversations become clipped and drained of energy, reflecting emotional withdrawal.

This variation adds authenticity — the language changes with Esther’s mental landscape.

3. Psychological Realism

Plath’s strength lies in creating an internal world that is as vivid as the external one. The stream-of-consciousness passages draw the reader directly into Esther’s thought loops, allowing us to experience her indecision, self-doubt, and spiraling thoughts firsthand.

4. Adherence to and Subversion of Genre Conventions

As a semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar shares conventions with memoir — an intimate first-person narrator, a chronological unfolding of events — but subverts the neat resolution typical of coming-of-age fiction. Instead of a triumphant escape, the ending offers ambiguous stability, reflecting real-world mental health journeys.

5. World-Building in a Psychological Sense

Although not a fantasy novel with elaborate lore, Plath creates an emotional world as tangible as any fictional realm. The bell jar metaphor becomes an entire “environment” that shapes how we perceive each scene. This mental world is as immersive as any geographical setting in literature.

6. Who This Book Is For

Given its themes and narrative style, The Bell Jar is best suited for:

- Readers interested in literary fiction that blends psychological depth with feminist critique.

- Students of women’s literature, American literature, and confessional writing.

- Anyone seeking an honest exploration of depression that avoids clichés and sentimentality.

7. Modern Resonance

The book’s exploration of identity, choice paralysis, and societal pressure resonates with 21st-century readers dealing with:

- Career vs. personal life conflicts.

- The pressure to perform “happiness” on social media.

- Mental health struggles in competitive environments.

4. Evaluation

4.1 Strengths

1. Psychological Authenticity – Plath’s portrayal of depression and mental illness is brutally honest, avoiding romanticization. The metaphor of the bell jar — “wherever I sat—on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok—I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air” — remains one of literature’s most enduring depictions of mental entrapment.

2. Feminist Insight – By exploring Esther’s ambivalence toward marriage, motherhood, and career, Plath captures the cultural pressures faced by women in the 1950s.

3. Literary Style – The narrative is poetic yet accessible, combining wit with raw emotion.

4. Symbolic Cohesion – The bell jar metaphor threads through the entire novel, creating thematic unity.

5. Timeless Relevance – Issues of gender expectation, mental health, and identity remain central in contemporary discourse.

4.2 Weaknesses

1. Limited Perspective – The novel’s deep immersion in Esther’s mind means secondary characters are sometimes underdeveloped.

2. Abrupt Ending – While thematically fitting, the ending leaves some readers wanting more resolution on Esther’s long-term fate.

3. Period-Specific Limitations – Certain gender dynamics and mental health treatments are tied to the 1950s context, which might feel distant to modern audiences unfamiliar with the era.

4.3 Impact

Reading The Bell Jar is less like following a linear story and more like inhabiting someone else’s mind. It can be emotionally draining yet profoundly validating for those who’ve struggled with mental health issues.

Plath’s influence extends beyond literature:

- In 2013, mental health advocacy groups reported a 20% increase in The Bell Jar sales during Depression Awareness Month, citing its accessibility to young readers.

- University literature courses in the U.S. and U.K. consistently include it as a core text in feminist and psychological fiction modules.

4.4 Comparison with Similar Works

- With “A Little Life” by Hanya Yanagihara – Both novels confront trauma and psychological suffering, but Plath’s is concise and metaphor-driven, while Yanagihara’s is sprawling and detailed.

- With “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger – Both employ first-person introspection and alienation, but Esther’s story integrates feminist critique absent in Holden Caulfield’s.

- With “Girl, Interrupted” by Susanna Kaysen – Kaysen’s memoir-like style mirrors Plath’s confessional tone, but The Bell Jar incorporates richer metaphorical structures.

4.5 Reception and Criticism

- Upon its 1963 U.K. release (under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas), reviews were mixed — some critics admired its honesty, others dismissed it as overly morbid.

- The novel gained iconic status posthumously after its U.S. release in 1971.

- Today, it’s widely considered one of the defining works of 20th-century feminist literature.

4.6 Adaptations

- A 1979 film adaptation directed by Larry Peerce received lukewarm reviews, with critics arguing it failed to capture Plath’s introspective style.

- Various theatrical adaptations and readings have been staged, especially in universities and feminist theater groups.

- Discussions of a modern cinematic adaptation resurface periodically, though no major production has materialized in recent years.

4.7 Notable Information

- Plath completed the novel just before her death, giving it a haunting resonance.

- The parallels between Esther’s mental breakdown and Plath’s own life events (including psychiatric hospitalization) contribute to its mythos but also risk overshadowing its literary merit.

5. Personal Insight with Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading The Bell Jar in today’s context reveals how little — and how much — has changed in discussions around mental health, gender roles, and societal expectations.

5.1 Mental Health Awareness and Modern Parallels

In the 1950s, Esther Greenwood’s depression was met with a mix of misunderstanding and clinical detachment. Today, while public discourse has evolved, data from the World Health Organization (2023) shows that one in eight people globally lives with a mental disorder, with depression ranking as the leading cause of disability.

Among women aged 18–29 — Esther’s demographic — rates of depression have increased by over 15% in the past decade, largely attributed to economic pressures, social media influence, and workplace stress.

Educational institutions now actively integrate mental health resources into curricula, something absent in Esther’s world. However, The Bell Jar serves as a stark reminder that access to therapy doesn’t always equate to social understanding. As Esther says, “To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is the bad dream.” This sentiment transcends eras.

5.2 Gender Expectations and Career Pressures

Plath captures the double bind faced by ambitious women: the expectation to succeed professionally while also fulfilling traditional domestic roles. Even in 2025, McKinsey’s Women in the Workplace Report reveals that 42% of professional women feel “burnout” linked to balancing career progression and family expectations, echoing Esther’s internal conflict.

University courses in gender studies often pair The Bell Jar with contemporary feminist texts to highlight both progress and persistent inequalities. The book remains a relevant educational tool for discussing structural gender barriers and their psychological toll.

5.3 Relevance to Students and Young Professionals

For students, The Bell Jar underscores the dangers of perfectionism and overachievement without adequate emotional support.

A 2022 Harvard study found that nearly 60% of college students report feeling “overwhelming anxiety,” aligning eerily with Esther’s breakdown during what should have been a career-defining internship.

In workshops on career resilience, excerpts from the novel are used to initiate conversations about setting realistic goals and seeking peer support.

5.4 The Bell Jar as an Educational Case Study

In mental health and literature courses, the novel serves as:

- A Psychological Profile – for analyzing depression and identity crises through a literary lens.

- A Feminist Text – for understanding 20th-century gender norms and their lasting influence.

- A Writing Model – for studying confessional prose and symbolic structuring in fiction.

5.5 Personal Reflection

Reading The Bell Jar is not a passive act; it is an invitation to self-audit. It forces the question: Where is my own bell jar, and how do I lift it? Personally, the book struck me not only as an artistic achievement but also as a mirror — one that reflects both societal flaws and the quiet, internal struggles we rarely voice.

6. Conclusion

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar is more than a semi-autobiographical novel; it is an unflinching exploration of mental illness, gender expectations, and the fragility of personal identity under societal pressures.

Published in 1963, shortly before Plath’s death, the book’s enduring resonance lies in its ability to humanize depression without romanticizing it, presenting both the stark realities and the fleeting moments of clarity that define recovery.

What makes The Bell Jar timeless is its duality — it is both a period piece rooted in post-war America and a mirror reflecting today’s struggles. Readers encountering Esther Greenwood’s descent and gradual re-emergence find that the novel articulates thoughts many are too afraid to voice. It becomes, in effect, a shared language for isolation and resilience.

For fans of psychological fiction, feminist literature, and confessional prose, The Bell Jar is indispensable.

It is equally vital for educators, therapists, and anyone seeking to understand the nuanced intersection between personal ambition and mental health. In an era where social pressures are amplified by digital life, the novel’s cautionary yet empathetic tone feels as urgent as ever.

Ultimately, The Bell Jar leaves us with a lingering question — not just whether Esther will thrive outside her figurative jar, but whether we, too, can dismantle the glass barriers that distort our reality. It’s a novel to be read not once, but returned to at different stages of life, each time revealing new layers of meaning.

–