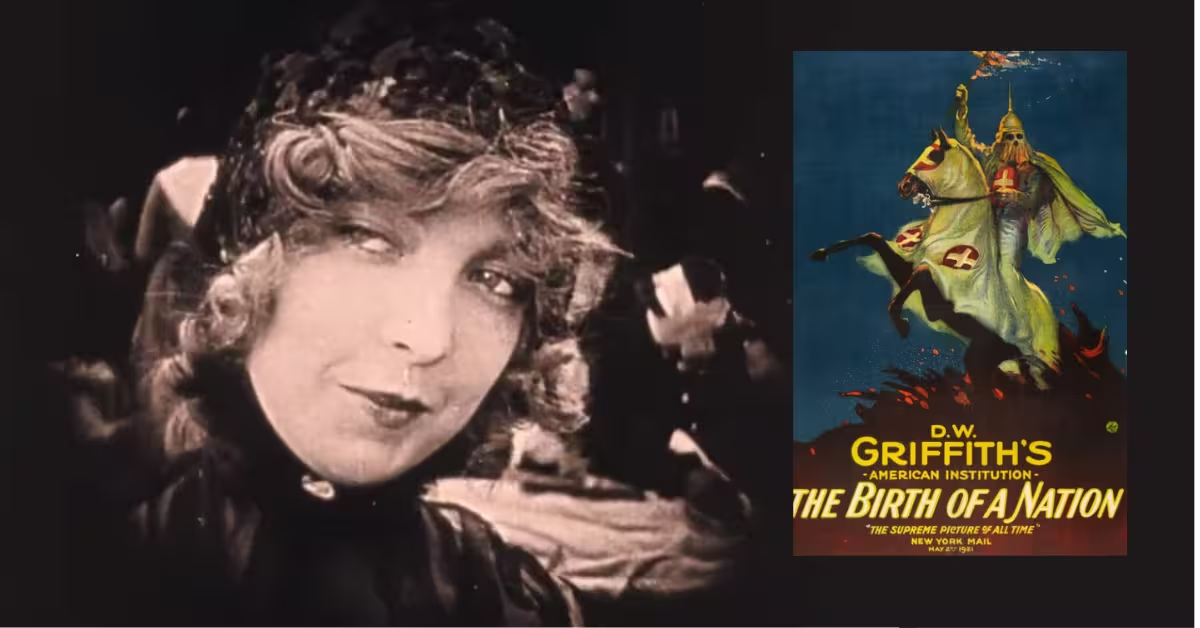

Here’s the hard truth: The Birth of a Nation (1915) is both the movie that turbocharged modern cinematic storytelling and a work of racist propaganda that helped popularize the Ku Klux Klan in the 20th century. My aim in this article is simple—explain the film in full (plot, techniques, performances, music), show where it innovated, and demonstrate how it did harm. I’ll lean on primary facts from the uploaded reference, film catalogs, and scholarship; I’ll also flag where the evidence comes from so you can verify every claim.

“The Birth of a Nation is a 1915 American silent epic… the first American-made film to have a musical score for an orchestra… and the first motion picture to be screened inside the White House.”

It is also widely called “the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history.”

Table of Contents

Background

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation is a 1915 American silent epic adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 novel/play The Clansman. Griffith co-wrote the screenplay with Frank E. Woods and produced it with Harry Aitken; it was the first non-serial American 12-reel feature, shown in two parts with an intermission.

It pioneered large-scale battle staging, close-ups, fade-outs, and arrived with an orchestral score and souvenir program; it also became the first feature screened inside the White House for President Woodrow Wilson.

The project’s source and financing were tightly linked to Dixon. Griffith paid $10,000 for dramatic rights (then ran short of cash), giving Dixon a 25% stake that ultimately made the author a fortune when the picture exploded commercially—an unusual deal at the time.

Principal photography ran July–October 1914, with location work at Big Bear Lake and extensive shooting on Griffith’s ranch in the San Fernando Valley; West Point engineers advised on the Civil War action and supplied artillery. Griffith shot roughly 150,000 feet (≈36 hours) and cut it down to 13,000 feet (just over three hours). The original budget, projected at $40,000, climbed to $100,000+ by completion.

Music was integral. Composer Joseph Carl Breil assembled a three-hour score mixing classical adaptations (including Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” for the Klan), popular tunes (“Dixie,” “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”), and original leitmotifs; the love theme, “The Perfect Song,” is often cited as the first marketed movie “theme song.” (West Coast premieres used a different compiled score by Carli Elinor; Breil’s was adopted for the New York run.)

From its January–February 1915 preview and Los Angeles opening, the film spread via roadshow engagements with aggressive publicity; by January 1916, New York alone logged 6,266 showings and an estimated 3 million attendees.

Even before release, the picture drew fierce criticism for its racist caricatures, use of blackface, and its heroic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan. The NAACP organized campaigns to block or censor it; it was banned in Ohio and in cities including Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Minneapolis. Griffith’s anger at censorship fueled his next epic, Intolerance (1916).

Financially, it became the industry’s defining blockbuster. Contemporary and later tallies suggest producer/distributor rentals of roughly $5–15 million by 1919, with total box-office business estimated between $50–$100 million in its initial runs—making it the highest-grossing film until Gone with the Wind (1939). Some trade figures were inflated and later corrected; scholars still debate exact receipts, but all agree the commercial impact was unprecedented.

The cultural impact was darker still. The film’s popularity inspired the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan within months and helped normalize white-supremacist myths in popular culture; decades later, heritage institutions preserve the film with heavy contextualization because its formal innovations and its harms are both historically significant.

Fast facts you’ll want up front

- Director: D. W. Griffith; stars: Lillian Gish, Henry B. Walthall, Mae Marsh. Running time: 12 reels (approx. 133–193 minutes). Budget: $100,000+. Box office: commonly reported in the $50–$100 million range over time (with distributor “rental” earnings much lower and contested).

- Music: Joseph Carl Breil’s compiled/original score; famous use of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” as the Klan’s leitmotif; the love theme, “The Perfect Song,” is often cited as cinema’s first marketed “theme song.”

- Premiere & run: Played 44 weeks at New York’s Liberty Theatre at $2.20 top ticket price (≈ $68 today).

- Protests & bans: Organized NAACP campaigns; bans in parts of Ohio, Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Minneapolis.

- White House: First feature screened at the White House (East Room) on Feb. 18, 1915; Wilson’s “lightning” endorsement line remains historically disputed.

- Measured harm: A Harvard/AER study finds screenings coincided with sharp spikes in lynchings and race riots, with one dataset showing lynchings rising fivefold in the month after local arrival; the roadshow reached 606 counties.

Plot

Content note: The film’s narrative depicts Black people with dehumanizing stereotypes, uses white actors in blackface, and glorifies the Ku Klux Klan. I describe what’s on screen to explain why the movie matters—ethically, politically, and historically.

Two families, two Americas.

D. W. Griffith adapts Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman into a two-part, three-hour epic that threads the Civil War and Reconstruction through the fortunes of two white families: the Northern, abolitionist-aligned Stonemans and the Southern, slaveholding Camerons.

The Stonemans are led by Congressman Austin Stoneman; the Camerons by Dr. Cameron and his son Ben (nicknamed “the Little Colonel”). Romantic crosscurrents link Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) and Ben, and also Flora Cameron (Mae Marsh) and younger Stoneman kin.

These domestic ties are Griffith’s melodramatic engine: the war tears the nation apart; love and “order,” in his telling, are restored only when white supremacy is reasserted. (On authorship, cast, and source, see AFI catalog and Britannica.

Part I: Civil War.

The first half races from antebellum tableaux to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre and the war’s human wreckage. Griffith stages battles with hundreds of extras framed to look like thousands, cutting rapidly to generate scale and momentum. (The uploaded reference stresses these craft landmarks and the historical span, including the Lincoln assassination and the film’s pioneering battle staging. )

The Camerons’ plantation life collapses; sons march to war; casualties mount. Ben Cameron earns his sobriquet “Little Colonel” leading a doomed charge. Wounded, he’s nursed in a Northern hospital where Elsie tends him—Griffith’s favorite kind of sentimental cross-section: private tenderness amid public catastrophe.

The war sequences demonstrate Griffith’s signature parallel editing and accelerated cutting to tighten emotional screws—military lines clash; families read letters; lovers wait. Shots iris in on faces, then fade out to black. These techniques weren’t invented wholesale by Griffith, but he standardized them for large-scale storytelling and taught audiences how to read them. (The uploaded reference explicitly notes the film helped pioneer closeups and fadeouts; it also highlights the scale of the battle set pieces. )

The turning point.

On the political stage, radical Republicans gain ascendancy. Griffith caricatures the Congressional program of Black citizenship and voting as chaotic “misrule,” preparing the ground for Part II’s central ideological move. The assassination of Lincoln is framed as a tragic severing of the “moderate” course—again, aligning the film with Lost Cause sentiment.

Part II: Reconstruction reimagined as a white nightmare.

Here the film becomes openly propagandistic. In Griffith’s retelling, the defeat of the Confederacy hands the South to “carpetbaggers,” “scalawags,” and newly enfranchised Black men (many portrayed by white actors in blackface). Stoneman’s protégé Silas Lynch, a mixed-race upstart in this narrative, rises to power.

The legislature—shown in a notoriously racist sequence—passes laws granting Black political rights while behaving with vulgarity. (The uploaded reference summarizes the film’s racist depiction of African Americans and heroic framing of the Ku Klux Klan. )

The Gus–Flora tragedy.

In the film’s most infamous plot line, Gus—a Black character (played by a white actor in blackface)—follows Flora Cameron through the woods. Pursued, terrified, and cornered, Flora leaps to her death from a cliff rather than be assaulted.

This sequence is edited for maximum shock and pity, with close-ups of Flora’s fear and Ben’s anguish when he finds her body. The Camerons and their neighbors lynch Gus, delivering his corpse to town in a brutal spectacle. The scene is a pillar of the film’s “cause and effect”: it justifies—in the film’s logic—the birth of a vigilante order.

“The Birth.”

Ben Cameron, mourning and enraged, founds the Ku Klux Klan, borrowing from “heroic” chivalric imagery. Griffith cuts between white-robed riders and communities in distress, setting up a series of “rescues.” The Klan storms a cabin where white refugees and loyal former enslaved people are besieged; it halts a forced marriage between Elsie and Silas Lynch; it then seizes the polls to “restore order.” These climax passages use rapid cross-cutting, tight closeups, rhythmic montage, and crowd choreography—formally dazzling, ideologically poisonous.

The finale.

After the Klan’s victories, Griffith stages a sentimental reconciliation of North and South (Stoneman–Cameron families united) under a banner of white rule. The final vision of heavenly peace—an allegorical tableau—intones that calm returns when “the right people” govern.

What the plot achieves—cinematically and politically.

For many first-time viewers, the whiplash comes from this collision: the film feels like modern cinema (its editing grammar, scale, and music) even while it preaches white supremacy. That friction is the central fact of The Birth of a Nation: the story makes its hateful claims more persuasive because the filmmaking is so forceful.

Direction & Cinematography

Griffith’s visual grammar.

Whatever else we say—and we must say a lot—the film standardized a feature-length cinematic vocabulary for American audiences: closeups, fade-outs, irises, cross-cutting, large-scale battle direction, and geographic continuity across massive scenes. The uploaded reference calls it “a landmark of film history… the first non-serial American 12-reel film… [that] helped to pioneer closeups and fadeouts… [with] a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands.”

The camera team—led by G. W. “Billy” Bitzer—was crucial to those results (see AFI catalog and Britannica credits).

Editing as persuasion.

Parallel editing amplifies melodrama (cabin siege vs. Klan charge). That momentum persuades many viewers to feel the story’s stakes—even when the stakes are fabricated. It’s not accidental: Griffith’s technique drives identification toward his chosen heroes.

Acting Performances

Lillian Gish (Elsie Stoneman) delivers gentleness and moral gravity that Griffith often relies on; Henry B. Walthall (Ben Cameron) gives a haunted, romantic lead turn; Mae Marsh (Flora) is pure pathos in the woods sequence; George Siegmann (Silas Lynch) and Walter Long (Gus) are the center of the film’s ugliest caricatures—crafted performances in the service of grotesque roles built on racist tropes. Cast and primary credits: ;

Script, Intertitles & Pacing

As a silent feature, the movie’s “dialogue” is intertitles—grand, sometimes pseudo-historical statements—paired with performance and music. The intertitles are where the film tries to launder opinion as fact, telling you Reconstruction was chaos and that vigilante “order” was noble. The pacing is deliberate in Part I (making room for battlefield spectacle and hospital sentiment) and relentless in the Part II climax, where rapid cutting makes the Klan’s ride feel inexorable.

One of the movie’s least-discussed innovations is its music. Composer Joseph Carl Breil built a roughly three-hour orchestral score combining adapted classics, rearranged popular melodies, and original cues—an ambitious practice for 1915.

The film’s West Coast première used an alternate compilation by Carli Elinor; Breil’s score was used in New York at the Liberty Theatre and in most showings beyond the West Coast. (Additional catalog confirmations: AFI and TCM list Breil as music credit.

Themes & Messages

The Lost Cause on celluloid.

The film peddles a myth: that Reconstruction was a catastrophic inversion of “proper” order and that the Klan rose nobly to save civilization. The uploaded reference states bluntly that the film portrays Black people as “unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women,” while the Ku Klux Klan is framed as a heroic force—exactly the political point of the source novel/play The Clansman.

Why that mattered beyond the screen.

According to the Library of Congress essay by Dave Kehr, the film “gave birth to the movies as an industry… and… contains perhaps the most virulently racist imagery ever to appear in a motion picture.”

As History.com notes, the movie’s depiction of the Klan as saviors helped revive the organization; the Klan used screenings and imagery as recruiting tools in the 1910s and 1920s.

Measured social harm.

Recent scholarship quantifies the damage. A 2023 American Economic Review study (Desmond Ang) exploited the movie’s five-year roadshow and found sharp spikes in lynchings and race riots in the month after the film arrived in a county.

Working papers and Harvard summaries provide further details and context. Some scholars critique aspects of the methodology, but the headline finding—that screenings coincided with increased racial violence—has survived peer review.

Reception, Protests, Box Office, and Afterlife

Audience response in 1915 split along predictable lines. Some critics marveled at the form; others condemned the content. The New York Times called it “melodramatic” and “inflammatory,” warning that it plucks at “old wounds.” The New Republic called it “aggressively vicious and defamatory” and a “spiritual assassination.”

Its commercial success was unprecedented. New York’s Liberty Theatre run—44 weeks at a top ticket price of $2.20—helped catapult the film; scholars reconstruct distributor rentals in the $5–$15 million range across the late 1910s, with total box-office receipts plausibly $50–$100 million (significant uncertainty remains due to states-rights distribution and underreporting).

But the cultural cost was catastrophic. Rigorous modern research has punctured any defense that it was “just a movie.” Desmond Ang’s widely cited study (American Economic Review) exploits the film’s staggered roadshow to show spikes in lynchings and race riots where and when the film arrived; one dataset finds lynchings rose fivefold in the month after local screening.

The film’s political endorsement aura also mattered. It became the first film screened at the White House (February 18, 1915); whether Wilson really said it was like “writing history with lightning” remains disputed, but the quote’s circulation functioned like an endorsement in popular memory.

Even the promotional ecosystem was toxic. Theaters received “advice sheets” detailing how to market the film—including, in some cases, segregated admission instructions—showing how exhibition practices entwined with Jim Crow norms.

And yet, the film industry and heritage institutions have kept it in view—not to celebrate its message, but because its formal innovations shaped cinema. The Library of Congress lists it in the National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant,” while contextual essays underscore both its craft and its racism; BFI programming and criticism often pair it with Intolerance or Within Our Gates (1920) to frame its legacy.

A few short quotations

- “The Birth of a Nation is a landmark of film history… the first non-serial American 12-reel film… first American-made film to have a musical score for an orchestra.”

- “The most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history.”

- “Breil created a three-hour-long musical score… combining adapted classics, popular melodies, and original music.”

- On NAACP protests and censorship calls surrounding the March 3, 1915 New York premiere.

- On roadshow screenings raising lynchings and race riots in counties afterward. (American Economic Association)

Comparison

- Gone with the Wind (1939) shares Lost Cause sympathies but wraps them in romantic gloss and later studio polish. Griffith’s film is rawer and more explicit in its racial ideology; both helped normalize myths about Reconstruction. (Uploaded PDF + Britannica context.) (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Intolerance (1916)—Griffith’s next epic—was partly a response to criticism. It multiplies cross-cutting into a grand thesis about persecution across ages; formally grander, ideologically evasive.

- Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920) is an explicit Black counter-narrative; it confronts lynching and Jim Crow head-on, exposing what Griffith prettifies.

- The Birth of a Nation (2016) (Nate Parker) reclaims the title to tell Nat Turner’s revolt—an intentional reversal of meaning and memory. (For accessible context, see Time on reclaiming the title.)

Audience Appeal / Suitability

Who it’s for: film students, historians, teachers with a framework for critical viewing, anyone studying media effects and racial politics.

Who should skip: casual viewers seeking “classic entertainment”; viewers (rightly) unwilling to sit through three hours of racist mythology.

“Awards”: None in the modern sense (feature film awards culture emerges later), but AFI and National Film Registry listings confirm its canonical status—precisely so we do not forget what powerful art can normalize.

Personal Insight

Watching The Birth of a Nation (1915) today feels like sitting behind the camera as power edits reality. The craft is seductive: the charging horses, the tight closeups, the way music lifts your heartbeat before you notice who the heroes are supposed to be. I caught myself admiring a montage, then felt a jolt of shame—because the montage isn’t neutral. It’s a machine that converts fear into certainty.

That’s why the film is still assigned in film schools and history seminars: not to celebrate it, but to study how aesthetics can launder ideology. The film’s two-family structure is the key. You’re asked to care about domestic happiness—love requited, children safe—and then you’re told those goods are possible only if a vigilante order rides. The emotional syllogism is simple: If you love Elsie, you must love the Klan. That’s propaganda elegance. And it’s devastating.

It also maps onto modern life more neatly than I wish. Media doesn’t just reflect the world; it tilts it. That’s not my hunch—it’s what the AER study finds when it shows lynchings and riots spiking after the movie’s local premiere. I don’t need econometrics to “feel” that truth, but I’m grateful for the receipts. We’re often told that images “merely” represent; in practice, they provoke, recruit, and ratify. People don’t leave their convictions at the theater door.

So what do we do with a film like this? Not bury it; not burn it; contextualize it. The Library of Congress preserved it to mark its aesthetic and historical significance—both the craft leap and the cultural injury. Teaching it alongside responses—Micheaux, later civil-rights cinema, and modern scholarship—makes the classroom a safer, sharper place.

I also think of the White House screening and the aura it conferred. (The uploaded reference notes that it was the first movie shown inside the White House.) The screen doesn’t just entertain; it legitimizes. Prestige spaces bless narratives. That’s true for museums, festivals, hit lists, algorithmic “Top 10s.” It’s a reminder to treat “buzz” not as wisdom, but as a social weather pattern someone set in motion.

There’s a temptation to say, “It was 1915; we know better now.” We do and we don’t. Our tools are sharper; our screens are everywhere; our edits are faster. The grammar Griffith helped standardize still works on us. That’s why this film, awful and ingenious, still matters—not as a relic on a dusty shelf, but as a manual on how stories win.

Pros and Cons

Pros

- Innovates large-scale editing, staging, and feature-length structure (battle spectacles; cross-cutting; iris and fade grammar).

- Ambitious orchestral score model for silent exhibition (Breil).

- Key performances (Gish, Walthall, Marsh) anchor the melodrama.

Cons

- Overt racist propaganda that glorifies the Klan and dehumanizes Black people.

- Documented harmful social effects around screenings (lynchings/riots).

- Historically mendacious account of Reconstruction that shaped public memory for decades.

Conclusion & Recommendation

Bottom line: The Birth of a Nation (1915) is a foundational film—artistically ambitious and technically formative—and a foundational lie. If you study film language, media power, American history, or propaganda, you should see it once, but only with critical framing and paired with counter-texts (e.g., Within Our Gates, civil-rights documentaries, primary Reconstruction sources). If you’re a casual cinephile in search of “the classics,” you can grasp its legacy through essays, clips, and scholarship without sitting through its full runtime.

Rating: 3.5/5 for historical/cinematic study value; 0/5 for ethics.

Sources & citations

- Film overview, first White House screening, innovations, racist depiction, and cast credits (uploaded PDF of Wikipedia article).

- AFI Catalog credits and production details. (AFI Catalog)

- Britannica summary (running time, credits). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Library of Congress: National Film Registry listing and essay. (The Library of Congress)

- History.com on the Klan revival and film’s influence. (HISTORY)

- AER (2023) and Harvard summaries on lynchings/riots after local screenings. (American Economic Association)

- Methodological critiques for balance. (econjwatch.org)