Last updated on September 2nd, 2025 at 02:26 pm

The Book Thief, written by Australian author Markus Zusak, was originally published in 2005 by Picador in Australia and Knopf Books for Young Readers in the United States. Since then, it has sold over 17 million copies worldwide and been translated into more than 40 languages. Its haunting narrative and deeply moving prose have made it a modern classic in contemporary historical fiction.

The book falls under historical fiction, uniquely narrated by Death, a literary innovation that adds both poignancy and a chilling omnipresence to the story. Set in Nazi Germany during World War II, The Book Thief explores the power of language, literature, and compassion in the face of overwhelming destruction.

Zusak was inspired by stories his parents told him about growing up in wartime Europe. The novel’s protagonist, Liesel Meminger, a foster girl living in the fictional town of Molching, represents the everyday German citizen caught between survival and silent rebellion. Through Liesel, Zusak paints a painfully real yet tender portrait of humanity during one of history’s darkest periods.

At its core, The Book Thief is not just a novel about war or even books. It is a profoundly emotional exploration of how stories save us, even when everything else is falling apart. Its strength lies in its unconventional narration, deeply drawn characters, and the emotional resonance it leaves with the reader. Despite its dark backdrop, it’s a story filled with hope, kindness, and the indestructible nature of the human spirit. It teaches us that even in times of death, it is the words we hold on to that keep us alive.

“I am haunted by humans.” – Death, The Book Thief, p. 550.

This single quote captures the entire essence of the book—Death watches, narrates, and yet is stunned by the beauty and brutality of human life.

Table of Contents

Summary of the Book

The Beginning of a Thief: Liesel’s Early Life & First Stolen Book

The Book Thief opens with one of the most unique narrative decisions in modern literature—Death is the narrator. The voice of Death is not cold or cynical, but strangely tender and introspective, often poetic. From the beginning, Death tells us, “Here is a small fact: You are going to die.” (p. 3). It sets the tone: blunt but filled with a haunting kind of beauty.

Liesel’s First Encounter with Death

The story begins in 1939 Nazi Germany, where Liesel Meminger, a young girl, is on a train with her brother and mother. Her brother, Werner, dies en route to their new home. This loss marks the beginning of Liesel’s lifelong relationship with death—and books.

At her brother’s snowy graveside, Liesel steals her first book: The Grave Digger’s Handbook. She cannot read it yet, but the act itself is symbolic. In a world where everything is being taken from her—her family, safety, and normalcy—she takes back control by stealing a word.

“She was the book thief without the words.” (p. 29)

Liesel is taken to the Hubermann family in the fictional town of Molching, near Munich. Hans Hubermann, her foster father, is a kind and gentle man with silver eyes and the patience of a saint. He is the one who teaches Liesel to read, slowly, in the basement, using the stolen Grave Digger’s Handbook. This becomes a key motif: words as resistance and survival.

His wife, Rosa Hubermann, is foul-mouthed but not unloving. She calls everyone “Saumensch” (a derogatory term), but she cooks, cleans, and protects Liesel in her own gruff way. Their poverty is palpable, yet their humanity is rich.

“The only thing worse than a boy who hates you: a boy who loves you.” (p. 52)

[On Rudy Steiner, Liesel’s neighbor and best friend]

Rudy Steiner: The Lemon-Haired Boy

Rudy is Liesel’s classmate, soccer partner, and closest friend. A boy full of dreams and foolish bravery, Rudy idolizes Jesse Owens, the Black American Olympic runner. He even paints himself black one day and races around the local track, which is both comical and politically dangerous in Hitler’s Germany.

Rudy and Liesel become inseparable. They steal together, run together, read together, and dream of a life beyond the war. Rudy’s love for Liesel is unwavering, though she never reciprocates in words—only through her loyalty.

“He does something to me, that boy. Every time. It’s his only detriment. He steps on my heart. He makes me cry.” (p. 531)

The Library Window

Liesel’s love for books grows. She begins “borrowing” books from the mayor’s wife, Ilsa Hermann, who notices Liesel lingering outside her large private library. This relationship is fragile at first, filled with unspoken grief—both have lost someone they love. Ilsa allows Liesel to read in the library, which becomes a sanctuary for her.

Eventually, when Ilsa cancels Rosa’s laundry services due to financial hardship, Liesel responds by “stealing” books—but Ilsa never stops her. Instead, she begins leaving the window slightly open, showing her quiet approval.

Hearts, Books, and Bombs: Liesel’s Growth in Molching

As the war intensifies, The Book Thief deepens in complexity, portraying how ordinary people endure the extraordinary. Markus Zusak doesn’t glorify survival—he shows how fragile, painful, and quietly noble it can be.

One night, Hans Hubermann brings home a stranger—Max Vandenburg, a Jewish man hiding from the Nazis. Max is the son of the man who once saved Hans’ life during World War I. Keeping Max in their basement is a dangerous act of resistance that could mean death for the entire family.

Max and Liesel become unlikely soulmates, bonded by nightmares and words. Both are haunted by loss, both are dreamers, and both believe in the healing power of stories. Max writes two books for Liesel, one of which—The Word Shaker—is a poetic metaphor showing how words can both destroy and heal.

“The words were on their way, and when they arrived, Liesel would hold them in her hands like clouds, and she would wring them out like the rain.” (p. 80)

Through Max, The Book Thief introduces its central idea: words are not neutral; they are weapons, and also salvation. Hitler uses words to control; Liesel uses them to heal.

The Power of Words

Liesel continues reading aloud during air raids, helping to calm terrified neighbors. Her voice becomes a source of comfort and unity in the community. These moments of storytelling in bomb shelters stand as powerful acts of defiance against fear.

When Ilsa Hermann gifts Liesel a blank book, Liesel begins to write her own story—The Book Thief—within the world of the novel. This metafictional twist is subtle but profound. The narrator—Death—eventually picks up her handwritten book from the rubble and tells us:

The Bombing of Himmel Street

Despite the small pockets of peace, death looms large. Eventually, Molching is bombed without warning. Liesel survives only because she was in the basement writing in her notebook. Everyone else she loves—Hans, Rosa, Rudy—is killed.

The aftermath is devastating. Liesel finds Rudy’s body and kisses him for the first and last time. Her sorrow is palpable and raw. Markus Zusak doesn’t soften the blow. He lets grief have its full weight and writes:

“She kissed him long and soft, and when she pulled herself away, she touched his mouth with her fingers… He was cold and motionless.” (p. 532)

In this scene, The Book Thief forces us to confront the reality of loss—not as a grand tragedy, but as an intimate shattering of a single life at a time.

Liesel’s Resurrection

After the bombing, Death finds Liesel’s book, dropped in the rubble. She is later taken in by Ilsa Hermann. Years pass. Death tells us how Liesel lives a full life, marries, has children and grandchildren.

When Death finally comes for Liesel, he returns her book and says:

“I am haunted by humans.” (p. 550)

This last line sums up Death’s narrative arc and the novel’s moral core—that humanity, for all its cruelty, also creates unbearable beauty.

As The Book Thief reaches its final chapters, what began as a story about a girl learning to read becomes a sweeping meditation on the power of words, the weight of grief, and the quiet acts of resistance that define true courage.

The Word Shaker: Max’s Gift and the Power of Story

Max Vandenburg, hidden in the Hubermanns’ basement, creates The Word Shaker, an allegorical story for Liesel. In it, Hitler plants trees with words, controlling minds and hearts. But one girl climbs the tallest tree and speaks her truth. Eventually, her words fall like seeds, breaking the dictator’s grip.

“The best word shakers were the ones who understood the true power of words. They were the ones who could climb the highest.” (p. 445)

This short story within the novel captures Zusak’s central message: language is the most powerful tool we possess. Hitler used it to destroy; Liesel uses it to rebuild.

Rosa, Hans, and Their Quiet Heroism

Hans Hubermann’s small rebellion—offering bread to a Jewish prisoner during a parade—gets him punished and sent to war. Rosa, though gruff and tough, kisses his accordion at night while he’s away. She keeps it on the table like a sacred relic.

“She didn’t speak. She just held the accordion and cried.” (p. 427)

Their love is not loud, but it’s deeply human. These quiet gestures—hiding a Jew, offering bread, treasuring music—become radical acts of decency.

The Bombing, Revisited

When the bombs fall on Himmel Street, The Book Thief does not flinch. The death toll isn’t summarized—it’s felt. Liesel finds her family and friends in rubble. The most heart-wrenching moment comes with Rudy.

She finally gives him the kiss he always asked for, but he is cold, lifeless.

“She kissed him and whispered goodbye. She cried over the boy with the lemon hair and skin like snow.” (p. 532)

These lines haunt the reader—and haunt Death, too. The narrator confesses multiple times how he cannot forget Liesel Meminger.

When Death finds The Book Thief, the actual notebook Liesel wrote during her time in the basement, he reads it and is forever changed.

“I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.” (p. 528)

This moment serves as a meta-ending. The novel we read is essentially Liesel’s own writing, preserved and retold by Death. This literary device adds a layer of authenticity and reverence—as if we’re reading a sacred document salvaged from the ashes of war.

Liesel’s Afterlife: Love and Legacy

After the war, Liesel is taken in by Ilsa Hermann, the mayor’s wife. Time passes. Liesel grows old, has a family, and lives a quiet, full life. When she finally dies, Death returns her book and tells her:

“I am haunted by humans.” (p. 550)

This closing line is one of the most quoted lines in modern fiction. It’s more than poetic—it’s a verdict on humanity: capable of cruelty, yes, but also of immeasurable beauty.

Setting of The Book Thief

Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief is set primarily in Molching, a fictional town located near Munich, Germany, during the years 1939 to 1945—the height of Nazi rule and World War II. Though fictional, the setting is firmly grounded in historical reality and plays a crucial role in shaping the novel’s atmosphere, characters, and themes.

Himmel Street: A Place of Loss and Love

The heart of the story beats on Himmel Street, a poor neighborhood where Liesel Meminger lives with her foster parents, Hans and Rosa Hubermann. “Himmel” means “heaven” in German, an ironic name given the suffering and death that takes place there. Still, it’s on this very street that Liesel finds safety, love, and the beginning of her moral education.

“The streets were ruptured veins. Blood streamed till it was dried on the road, and the bodies were stuck there, like driftwood after the flood.” (p. 532)

— Describing Himmel Street after the bombing

This contrast—between the ordinary and the horrific—underpins much of the narrative tension in The Book Thief. The setting becomes a character itself, witnessing joy, rebellion, and unimaginable grief.

The Mayor’s Library: A Sanctuary of Words

Another key location is the mayor’s house, particularly his wife Ilsa Hermann’s private library. This becomes a symbolic refuge for Liesel. In a world defined by censorship and propaganda, the library offers intellectual freedom, curiosity, and solace.

“She was the book thief without the words.” (p. 287)

It’s in this library that Liesel reads forbidden books, learns empathy, and eventually finds her voice as a writer. The setting here contrasts with the public burning of books in Nazi Germany, reinforcing the novel’s central message: words matter.

Germany itself is a looming presence—air raid sirens, parades of Jewish prisoners, Nazi Youth meetings, and bombings shape the lives of every character. The novel’s setting reminds readers that no one was untouched by the war, and that even the seemingly powerless—like Liesel—can resist in small but meaningful ways.

“It’s hard to live in a world that turns you into a stranger to yourself.” (p. 356)

In conclusion, the setting of The Book Thief isn’t just background scenery. It’s a mirror to human nature, revealing how love, loss, rebellion, and silence are all forged in the fire of place and time.

Character Analysis – The Book Thief

Markus Zusak populates The Book Thief with unforgettable characters—many of them ordinary people surviving an extraordinary time. What makes them compelling isn’t grand heroism but their quiet resilience, contradictions, and moral clarity in the face of cruelty.

Liesel Meminger: The Word-Loving Survivor

The protagonist, Liesel, begins her journey as a frightened, illiterate girl whose brother dies and whose mother disappears under Nazi persecution. Yet she grows into a fierce, loving, and literate young woman who resists tyranny—not with weapons, but with words.

Liesel is driven by grief, curiosity, and a deep hunger for meaning. Her transformation unfolds with every book she steals or receives—from The Grave Digger’s Handbook to The Word Shaker. Her voice matures in tandem with her moral compass.

Hans Hubermann: The Accordion-Playing Father Figure

Hans, Liesel’s foster father, may be the soul of the novel. Gentle, principled, and patient, he teaches Liesel to read, comforts her during nightmares, and risks his life by hiding Max, a Jewish man, in his basement.

“His silver eyes were gentle. There was a slowness to them.” (p. 34)

Hans doesn’t make loud declarations. Instead, he acts—giving bread to prisoners, refusing to join the Nazi Party, playing the accordion during bombings. His quiet strength is a direct contrast to the era’s loud brutality.

Rosa Hubermann: The Tough Love Guardian

Rosa is a woman of few kind words and many curses, but beneath her roughness lies deep loyalty. While she often calls Liesel “Saumensch” (a German insult), she fiercely protects her family. She even embraces Max despite the danger he brings.

“She looked like a small wardrobe with a coat thrown over it.” (p. 36)

Her love is nonverbal and fierce, shown not in hugs but in perseverance, sacrifice, and the sacred respect she gives Hans’s accordion while he’s away at war.

Rudy Steiner: The Lemon-Haired Best Friend

Rudy is Liesel’s best friend, partner in crime, and the boy who constantly asks for a kiss. Funny, athletic, and rebellious, Rudy is unforgettable for painting himself black in admiration of Jesse Owens, defying Nazi ideals.

“He was the crazy one who painted himself black and defeated the world.” (p. 60)

He represents lost potential, the tragedy of youth caught in ideology. When Rudy dies in the bombing, Liesel finally kisses him—a moment of heartbreaking closure.

Max Vandenburg: The Word Warrior

Max, the Jewish man hidden by the Hubermanns, becomes Liesel’s soulmate in suffering and stories. He gifts her The Word Shaker, a book that reflects their shared battle against hatred through imagination and truth.

“When life robs you, sometimes, you have to rob it back.” (p. 445)

Max’s guilt over endangering the family and his identity crisis as a Jew in hiding are powerfully rendered. His bond with Liesel deepens the story’s theme: words can heal, unite, and give voice to the silenced.

Death: The Narrator Who Can’t Look Away

One of the novel’s most unique characters is its narrator: Death. He’s not cold or sinister—he’s weary, poetic, and even compassionate.

“I am haunted by humans.” (p. 550)

Death offers a detached yet emotional lens, witnessing the atrocities of war but also marveling at human resilience. His perspective adds a philosophical layer, forcing readers to reflect on mortality, memory, and meaning.

Character Connections:

- Hans & Rosa = Parental warmth in cold times

- Liesel & Max = Survivors connected by story

- Liesel & Rudy = Youthful rebellion and unspoken love

- Liesel & Death = A writer and her eternal reader

Each character in The Book Thief is more than their role. They’re deeply human, often flawed, always enduring.

Writing Style and Structure – The Book Thief

Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief doesn’t just tell a story—it paints, whispers, and weeps. The novel’s unique writing style and structure are a big reason it continues to captivate millions. Zusak’s techniques elevate what could’ve been a standard historical tale into something timeless, lyrical, and deeply human.

Narrative Voice: Death Speaks

Perhaps the most daring choice in The Book Thief is having Death as the narrator. But this isn’t the Death of horror films—it’s a gentle, exhausted observer, poetic and haunted.

“Here is a small fact: You are going to die.” (p. 3)

By breaking the fourth wall and addressing the reader directly, Death sets an intimate and philosophical tone. He interjects with bold-font observations, fragments of thoughts, and occasional spoilers:

“A small announcement about Rudy Steiner. He didn’t deserve to die the way he did.” (p. 241)

Instead of ruining suspense, this pre-spoiling deepens emotional impact. Knowing a character’s fate, we watch their every moment more closely, more tenderly.

Language: Poetic, Inventive, Raw

Zusak’s prose is lush with metaphor and unexpected imagery. He often uses personification and synesthesia:

“The sky was the color of Jews.” (p. 349)

Shocking, jarring phrases like this force readers to feel the injustice, rather than just observe it. Color, sound, and emotion blur together in his writing, reflecting how children like Liesel perceive the world.

Words aren’t just tools in this novel—they’re living forces. Liesel learns that they can destroy (Nazi propaganda) or heal (The Word Shaker). Zusak mirrors this power in his own writing.

Structure: Nonlinear, Fragmented, Focused

The Book Thief isn’t told in a straight line. It jumps in time, offers snippets of scenes, and frames the story through Death’s memory. Each chapter begins with a heading and a bold list that hints at what’s coming.

This structure helps readers pause, digest, and reflect. It also mimics the chaos of war—nothing is neat, and everything is uncertain.

Dialogue: Honest and Character-Driven

The dialogue in the book is raw, natural, and often humorous, even in dark moments. Rosa Hubermann’s constant swearing, Rudy’s boldness, and Hans’s calm tone are all reflected in how they speak.

“Saukerl!” (Rosa’s favorite insult)

“I’m not Hitler.” — Rudy, after painting himself black like Jesse Owens.

Zusak’s use of German phrases like “Saumensch” and “Watschen” adds authenticity and a cultural rhythm without overwhelming non-German readers.

The inclusion of fictional books like The Grave Digger’s Handbook and The Word Shaker adds depth and layers. These books mirror Liesel’s emotional journey and provide alternate storytelling methods—drawings, poems, fables.

These embedded texts remind us that The Book Thief is, at its core, a story about the power of stories.

Unusual Elements That Work

- Spoilers that heighten tension

- Bold-font interjections for emphasis

- Frequent use of lists, e.g., “5 Facts About Liesel’s Next Theft”

- Visual spacing and breathing room between thoughts

All these give the novel a visual and emotional rhythm rarely seen in historical fiction.

In Summary: Markus Zusak uses poetic language, a fragmented timeline, and a tender, philosophical narrator to create a book that reads like a memory wrapped in art. His style brings emotion to history and gives voice to the voiceless—not through grand declarations, but through whispers between the bombings.

Awesome! Let’s now explore the core ideas that give The Book Thief its emotional and intellectual power.

Themes and Symbolism – The Book Thief

Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief isn’t just a novel about war. It’s a meditation on language, humanity, death, resistance, and the enduring light of kindness in darkness. Through deeply symbolic storytelling, Zusak weaves universal truths into a historical narrative.

1. The Power of Words

Above all, The Book Thief is a novel about words—their ability to save or destroy, heal or corrupt.

Liesel begins the story illiterate, powerless. But as she learns to read, she gains agency, identity, and resistance. Words become her weapon against Nazi propaganda, fear, and grief.

“She was the book thief without the words. But trust me, the words were on their way, and when they arrived, Liesel would hold them in her hands like clouds…” (p. 80)

Even Hitler is framed as a manipulator of words, not just a tyrant. Max writes in The Word Shaker:

“The Führer decided that he would rule the world with words. ‘I will never fire a gun,’ he devised. ‘I will not have to.’” (p. 445)

This theme makes a powerful argument: language is not neutral. In the wrong hands, it can incite genocide. In the right hands, it can become a sanctuary.

2. Death as a Witness to Humanity

By making Death the narrator, Zusak asks us to see beyond stereotypes. Here, Death is compassionate, exhausted, and burdened by what he sees. He collects souls gently, observing life with melancholy reverence.

“I’m always finding humans at their best and worst. I see their ugliness and their beauty, and I wonder how the same thing can be both.” (p. 550)

Death doesn’t judge—he marvels. His presence reminds us of life’s fragility, and his voice becomes the moral lens of the novel. He isn’t scary—he’s tired of watching suffering.

3. The Meaning of Home and Family

Liesel’s journey is marked by loss and found-family. After her mother disappears and her brother dies, she’s adopted by Hans and Rosa Hubermann. Though rough around the edges, they become her true parents.

“It was strange to find the words to describe the feeling of safety.” (p. 109)

Even hiding Max in the basement deepens this idea: love is risk, sacrifice, and loyalty in action, not blood.

Rudy, too, becomes part of this chosen family. In a world that’s tearing people apart, Zusak paints a picture of family as something you build and defend with fierce devotion.

4. The Innocence and Destruction of Childhood

The book juxtaposes Liesel and Rudy’s playful mischief with the brutal realities of war. They steal books and apples, race in the streets, and dream of Jesse Owens—while bombs fall and Jews march through town.

This stark contrast highlights the tragedy of war stealing youth.

“You’re stealing books? Why?” Rudy asked.

“When life robs you, sometimes, you have to rob it back.” (p. 288)

That line defines The Book Thief’s core irony: children steal to feel whole, while nations steal lives for power.

5. Identity, Guilt, and Memory

Max represents the theme of guilt and identity. As a Jew in hiding, he feels like a burden. His gift to Liesel, The Word Shaker, is more than a story—it’s a manifesto of love, survival, and self-worth.

“I am not worth this,” Max often tells Hans. But by writing, he reclaims a sense of self.

Similarly, Liesel processes trauma by writing her own story. After the bombing, it’s her book that Death finds—her words that keep her alive in memory:

“I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.” (p. 528)

6. Acts of Resistance

The book emphasizes quiet defiance over violence. Hans gives bread to Jews. Rosa hides a Jew. Liesel steals banned books. These are all small, risky, rebellious gestures—symbols of humanity in a dehumanizing world.

“The only thing worse than a boy who hates you: a boy who loves you.” (p. 238)

Even this quote carries multiple meanings—loving, in such times, is dangerous. But they love anyway.

Symbolism in the Book

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Books | Freedom, resistance, memory, survival |

| The Accordion | Comfort, Hans’s presence, hope |

| The Word Shaker (book) | Max and Liesel’s bond; the resistance of storytelling |

| Bread | Shared humanity; acts of rebellion |

| Snow in the basement | A moment of magic amidst war, innocence preserved |

In Summary: The Book Thief teaches us that even during the darkest chapters of history, stories, kindness, and courage endure. Words can enslave or liberate. Family can be found, not inherited. And even Death can cry.

Genre-Specific Elements & Reader Recommendation

Genre: Historical Fiction with a Literary Twist

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak falls squarely within historical fiction, but it pushes the boundaries of the genre through its unconventional narrative voice (Death) and a deep literary sensibility. Unlike most WWII novels, this isn’t about soldiers or generals—it’s about the forgotten voices: a girl, her stolen books, her basement friend, and the daily humanity of ordinary Germans.

This genre-bending choice makes the novel not just a document of survival, but also a meditation on storytelling itself.

World-Building and Dialogue

While not a fantasy novel, the world-building in The Book Thief is rich and immersive. Zusak reconstructs 1940s Molching with sensory precision: the smell of smoke during bombings, the silence of an empty library, the rattle of a battered accordion.

“There were stars,” Death says. “They burned my eyes.” (p. 537)

— A line both poetic and jarring in its surreal realism.

The dialogue is crisp, character-driven, and often darkly humorous. Rosa’s swearing (“Saumensch!”) or Rudy’s bravado about kissing Liesel balance out the grief and tension with emotional authenticity.

Narrative Innovation

Few books in historical fiction take the risk of making Death the narrator. But Zusak’s gamble pays off. It allows him to:

- Shift perspectives seamlessly

- Foreshadow with eerie calm

- Reflect on mortality without being moralizing

- Break narrative conventions without losing clarity

Death’s voice is both omniscient and personal, delivering empathy with detachment. It’s literary fiction layered onto historical fiction.

Who Should Read The Book Thief?

This book is perfect for:

- Teens to Adults (recommended for 14+)

- Fans of historical fiction like All the Light We Cannot See or The Diary of Anne Frank

- Readers interested in WWII literature from a civilian lens

- Writers or literature students who want to study experimental narration and symbolism

- Anyone who loves language, philosophy, and soulful storytelling

It’s particularly powerful for educators or students who want to explore themes like power, propaganda, empathy, loss, and literacy.

Trigger Warnings (for sensitive readers):

- War violence

- Bombings

- Death of children and adults

- Holocaust references

- Racist language (used in historical context)

In Summary: The Book Thief doesn’t just follow genre rules—it redefines them. With its poetic prose, symbolic storytelling, and empathetic voice, it transcends mere historical fiction and becomes a universal story about why we read, write, and remember.

Evaluation: The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

✅ Strengths of the Book

1. Narrative Brilliance – Death as Narrator

The most compelling strength of The Book Thief is the narrative voice. By choosing Death to narrate the story, Zusak immediately separates this novel from traditional WWII fiction.

“Here is a small fact: You are going to die.” (Prologue)

From this opening line, Death becomes a poetic philosopher—part observer, part mourner, part storyteller. This creates a narrative that’s hauntingly beautiful, introspective, and deeply human.

2. Deep Emotional Resonance

The bond between Liesel and her foster father Hans, her friendship with Rudy, her care for Max—all build a tapestry of raw emotional truth. When the bombing kills everyone Liesel loves, we feel the weight of it because Zusak builds intimacy without sentimentality.

“She leaned down and looked at his lifeless face and Leisel kissed her best friend, Rudy Steiner, soft and true on his lips.” (p. 536)

That moment lands like a blow to the chest.

3. Literary Style and Language

Zusak’s prose style combines poetic fragments, metaphors, and unexpected imagery:

“The sky was the color of Jews.” (p. 349)

— This line jolts you. It’s uncomfortable, but unforgettable.

His style may polarize readers, but its uniqueness amplifies the novel’s themes.

4. Themes and Symbolism

From the accordion symbolizing hope, to books representing rebellion, The Book Thief is layered with metaphors that reward deep reading. It’s a novel that lingers long after it ends.

❌ Weaknesses of the Book

- Pacing Issues

The middle of the book occasionally sags—some readers may find the buildup too slow. Death’s frequent interruptions, while thematically rich, can sometimes disrupt narrative momentum. - Foreshadowing Fatigue

Death often spoils future events early (e.g., revealing Rudy’s death pages before it happens). For some, this adds dramatic irony; for others, it may reduce emotional tension. - Stylistic Barriers

Zusak’s lyrical language and fragmented syntax might not appeal to readers who prefer a more straightforward storytelling approach.

“A small note from your narrator: I am haunted by humans.” (p. 550)

— A sentence that’s poetic, but also self-consciously literary.

Emotional and Intellectual Impact

Reading The Book Thief feels like experiencing beauty in brokenness. The book is a masterclass in showing that:

- Words are not just tools; they’re weapons, healers, homes.

- Even in death, there’s grace and reflection.

- Amid war’s inhumanity, human connection remains our most powerful rebellion.

It pushes readers to rethink morality, silence, resistance, and the legacy of trauma—making it both a timeless and timely piece.

Comparison with Similar Works

| Title | Comparison |

|---|---|

| Night by Elie Wiesel | Both explore Holocaust trauma, but Night is memoir, stark and sparse, while The Book Thief is poetic fiction |

| All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr | Similar lyrical prose and WWII setting, but Book Thief focuses more on everyday German civilians |

| The Diary of Anne Frank | Anne and Liesel both document war with honesty, but Liesel writes fictionally while Anne’s diary is historical |

| Life is Beautiful (film) | Both balance light and dark; humor and horror; innocence and tragedy during the Holocaust |

Reception and Criticism

- Published in 2005, The Book Thief became an international bestseller, translated into over 40 languages, selling over 17 million copies globally.

- It spent over 230 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list.

- It won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, among many others.

However, critics were divided:

- Some praised the inventive narration and emotional depth.

- Others found the prose too affected or overly stylized.

Still, its impact on YA and adult audiences alike is undeniable.

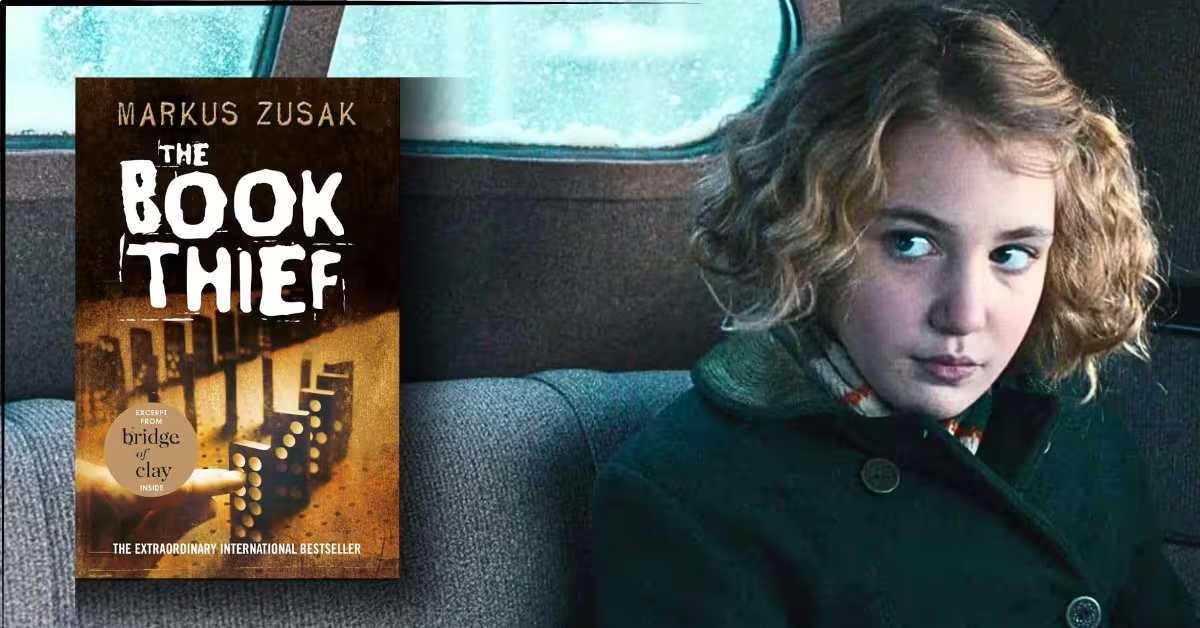

Adaptation (2013 Film)

- Directed by Brian Percival

- Starring Sophie Nélisse as Liesel, Geoffrey Rush as Hans, and Emily Watson as Rosa.

- Received mixed reviews (Metacritic: 53/100), but the performances and visuals were praised.

However, many felt the film lacked the emotional gravity and literary texture of the book. The voice of Death was toned down, and much of Zusak’s lyricism was lost in translation.

Other Notable Info

- The Book Thief is frequently included in school curricula, often for grades 9–12.

- It has been challenged in schools for profanity, violence, and disturbing imagery, but is also defended as an essential historical fiction text.

- Zusak has said the book took him over 5 years to write.

Personal Insight with Contemporary Relevance

Reading Death’s Perspective in a Time of Uncertainty

When I first read The Book Thief, it wasn’t just a novel — it was a mirror held up to the absurdity and beauty of human life. Told through Death’s eyes, it challenges us to understand mortality not as an end, but as a witness to our choices. In an era still healing from global trauma—be it war, pandemics, or injustice—Zusak’s words carry a haunting resonance:

“Even death has a heart.” (p. 242)

— A line I kept returning to, especially when the world outside my window felt fragile.

Why It Belongs in the Classroom Today

The Book Thief offers rich interdisciplinary potential in education:

- Literature: Analyze narrative technique, structure, and style. Compare with other WWII fiction or poetic prose.

- History: Explore how Nazi Germany impacted not just Jews, but everyday German families who were complicit, resistant, or indifferent.

- Civics/Ethics: Discuss moral choices—like Hans hiding Max, or Rudy’s silent defiance—and their relevance in today’s conversations on allyship and resistance.

- Creative Writing: Students learn how unconventional narration (like personified Death) can expand the scope of fiction.

In short, it’s not just a book. It’s a tool for empathy-building and critical thinking.

Lessons for a Digital Generation

In the age of social media, where attention spans are short and stories fleeting, The Book Thief teaches us to slow down. To savor language. To record life’s stories—even the painful ones.

Liesel’s hunger for books reminds us that even in darkness, reading is an act of rebellion. Even now, in places where access to literature is limited or censored, Liesel’s character inspires a quiet revolution.

The book changed how I grieve. After losing a friend, I found myself echoing Death’s words:

“I am haunted by humans.” (p. 550)

I understood that storytelling can be a vessel for grief. Like Liesel, we write, remember, and rebuild ourselves through language, memory, and shared humanity.

Global Relevance: War, Words, and Witnessing

The themes of The Book Thief—fascism, propaganda, innocence corrupted, silence vs. speech—are shockingly relevant today. Whether it’s books being banned or narratives controlled, Zusak’s work reminds us:

“Words are life.” (p. 521)

And in the hands of the wrong people, they’re also weapons.

In sum, this isn’t just a war novel. It’s a novel about who we become when we are tested. A book that urges every reader—student, teacher, thinker—to be a witness, a writer, and above all, a human who dares to feel.

Conclusion – The Book Thief

A Powerful Story That Transcends Time

The Book Thief is not just another novel set during World War II—it’s an unforgettable, poetic meditation on the power of language, the beauty of resistance, and the resilience of the human spirit. Markus Zusak’s decision to narrate the story through Death turns the book into something almost mythic. We’re not just watching Liesel’s life—we’re seeing humanity through the eyes of a cosmic observer, one that is equally awed and burdened by our choices.

“I’m always finding humans at their best and worst. I see their ugliness and their beauty, and I wonder how the same thing can be both.” (p. 491)

— This single quote captures the novel’s soul.

Why It Still Matters Today

We live in a world where words are both feared and used carelessly. From fake news to propaganda to cancel culture, the theme of word as weapon is more relevant than ever. Zusak reminds us that stories can preserve dignity when history tries to erase it. Liesel’s story becomes all our story: the need to speak when it’s dangerous, to read when it’s forbidden, and to love even when loss is inevitable.

“She was the book thief without the words.” (p. 521)

— But by the end, she finds them. And so must we.

Final Verdict

If I had to summarize The Book Thief in one phrase, it would be: tragic beauty. It’s a novel that will break your heart and then teach you how to rebuild it with books, friendship, and meaning. From the quiet nobility of Hans Hubermann to the wild devotion of Rudy Steiner, this book is a masterclass in emotional storytelling.

Highly recommended. Whether you’re a lover of historical fiction, poetic prose, or simply want to read something that will leave you changed—The Book Thief deserves a place on your shelf and in your memory.