We live in a world where women’s lives are shaped by invisible networks, institutional misogyny and buried histories—and most of that power operates in the dark. The Burning Library by Gilly Macmillan turns those shadows into a thriller, asking what happens when centuries of secret women’s power finally collide in the open.

At its heart, The Burning Library suggests that knowledge—especially women’s knowledge—has always been a battleground, and that who controls the archive controls the future.

When Macmillan imagines rival women’s secret societies fighting over a single, world-changing manuscript, she’s tapping into very real patterns of gender, violence and control.

Globally, UN Women estimates that about 840 million women—almost one in three—have experienced physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, with little progress in two decades.

At the same time, women are more present than ever in higher education (UNESCO reports roughly 113 women enrolled for every 100 men in tertiary education worldwide in 2023), yet their representation collapses as you move into senior academic and leadership roles.

Meanwhile, rare books and manuscripts have become a high-stakes asset class, with auction houses reporting 23% growth in global manuscript sales in 2024 alone, deepening the link between cultural heritage and financial power.

All of that sits in the background of The Burning Library’s fictional “Book of Wonder”: a single text that can tilt the balance of power between secret networks of women—and, indirectly, the men they influence.

If you love dark-academia thrillers, conspiracies wrapped around rare manuscripts, and morally tangled heroines like in The Secret History or Alex Michaelides’s The Maidens, The Burning Library is very likely your thing.

If you prefer tightly contained domestic suspense, hate multiple points of view, or get frustrated by intricate conspiracies and academic detail, this book may feel overstuffed, just as Publishers Weekly and several early reviewers have cautioned.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

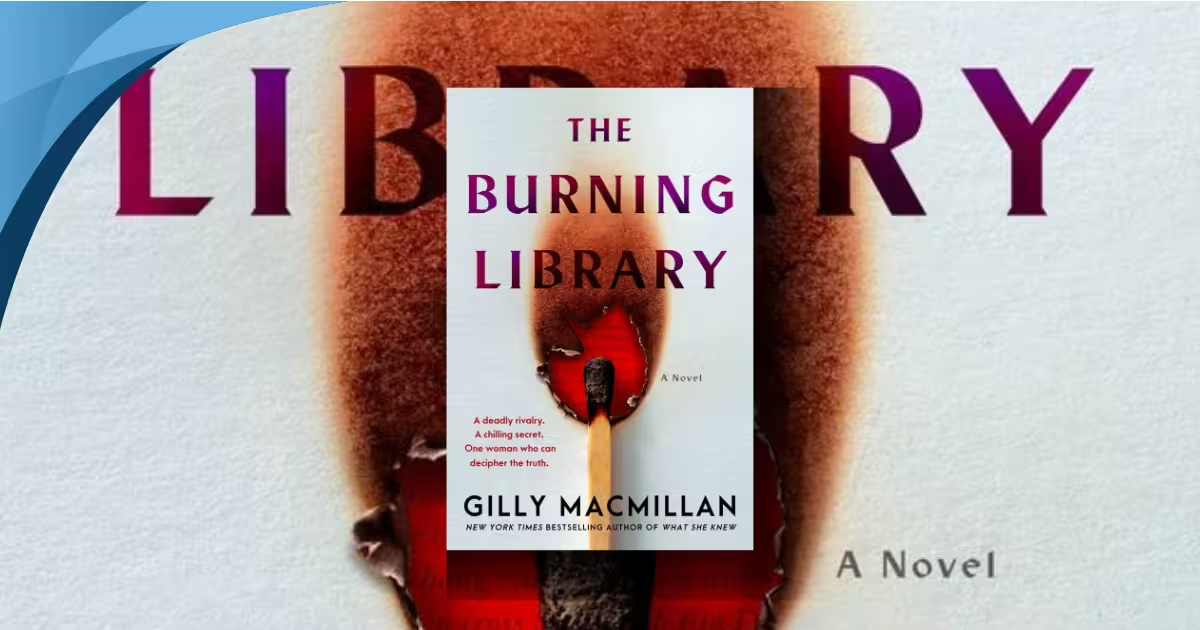

Gilly Macmillan’s The Burning Library is a dark-academia mystery-thriller first published in November 2025 by William Morrow in the US and John Murray / Hachette in the UK. (

The novel runs to roughly 300–500 pages depending on the edition (Goodreads lists 304 pages for the US hardback and review outlets quote 496 pages for another edition), and it has already earned a LibraryReads Hall of Fame spot for November 2025—an indication that North American librarians see it as a standout in popular fiction.

Macmillan herself is an established crime writer: a New York Times and Sunday Times bestseller, Edgar Award–nominated, with earlier books such as What She Knew, The Nanny and The Manor House translated into over twenty languages. (

She studied History of Art at Bristol and the Courtauld Institute, and worked with major art institutions before turning to crime fiction—a background that absolutely shows in the densely researched manuscript culture of The Burning Library.

When I read it, my sense was that Macmillan wasn’t just trying to tell a good story about scholars and secret societies; she was asking who gets to decide what counts as “important” knowledge in the first place.

At the plot level, The Burning Library centres on Dr Anya Brown, a brilliant young palaeographer with a near-perfect visual memory, who has made her name working on the notorious real-world Voynich manuscript.

Anya is recruited to the elite—and suspiciously opaque—Institute of Manuscript Studies in St Andrews, where she’s drawn into a centuries-long conflict between two all-female secret societies: the radical Fellowship of the Larks and the conservative Order of St Katherine (the “Kats”), both hunting a legendary lost text known as The Book of Wonder.

Running alongside Anya’s storyline is the perspective of Clio Spicer, a Scotland Yard detective in the Art and Antiques Squad, investigating a string of suspicious deaths and thefts linked to rare textiles and manuscripts.

The book’s central thesis, as I read it, is that women’s power—cultural, political, familial—has often been forced into secrecy, and that secrecy corrodes even the best intentions over time.

Both the Larks and the Kats started as attempts to help women survive in hostile structures; both have become power-hungry, willing to kill to secure their version of “the greater good”.

In that sense, The Burning Library isn’t just about a manuscript at all: it’s about what we will sacrifice to own the story the world tells about us.

2. Background

As a reader, what hooked me before page one was how closely the novel’s premise mirrors the world outside it.

We know, statistically, that women’s lives are still shaped by violence and control: WHO and UN partners estimate about 840 million women worldwide have experienced intimate partner or sexual violence, a figure that has barely shifted in twenty years.

In the EU alone, surveys suggest one third of women have experienced physical or sexual violence, with an economic cost of around €289 billion a year, while a UN-backed report in 2024/25 found that 140 women and girls a day are killed by their partners or relatives.

At the same time, women like Anya are more visible than ever in academia.

UNESCO and national agencies report that women now outnumber men in global higher-education enrolment (113 women per 100 men), and UK data show women forming the majority of students but fading sharply in senior posts and decision-making.

Macmillan sets The Burning Library precisely in that tension: a hyper-educated woman who lives in the world of elite manuscripts, but whose career, family life and bodily safety are all shaped by structures mostly run by men.

When Anya reflects that she can’t accept a dream job at Yale because her mother’s cancer and her love for Sid keep her tied to the UK, you feel the collision of professional aspiration and the unpaid care work that still falls disproportionately on women.

Add to that the rare-book market itself, which is no longer just a scholarly playground.

Auction houses and insurers now treat rare books and manuscripts as a niche investment class, with Bonhams’ 2025 manuscript review citing $147 million in global sales in 2024, up 23% on the previous year.

At the same time, think pieces and legal cases keep exposing stolen manuscripts, colonial loot and provenance failures that haunt institutions like the British Library.

When The Burning Library imagines a single manuscript—the Book of Wonder—capable of conferring vast power on whichever network of women controls it, it isn’t really exaggerating.

Knowledge, in this world, behaves exactly like money and political capital: it accumulates in certain hands, under certain names, behind certain closed doors.

Even the BBC has a long history of grappling with secrecy and hidden power: in 1987 it aired the documentary series Secret Society, about state secrecy and lack of accountability, so controversial that police raided the BBC’s Scottish HQ before broadcast.

Macmillan’s novel simply lifts that culture of secrecy out of government and places it into the parallel world of manuscripts, libraries and women’s clandestine networks.

3. The Burning Library summary

I’ll walk through the story in broad strokes here, including late-book developments, because the aim is for you not to need to go back to the novel to understand its structure and concerns.

3.1 Opening

The book opens with the death of Eleanor Bruton, whose body is found on a cold, windswept shore in Scotland’s Western Hebrides.

She’s connected to a mysterious piece of embroidery and to the Larks, one of the two secret societies, though we don’t fully understand that link until later.

From there, the narrative splinters into multiple points of view.

We meet Anya Brown, a working-class, first-generation academic with an extraordinary visual memory who has just achieved something sensational: she’s decoded the final folio of the Voynich manuscript, a real fifteenth-century codex written in an unknown script that has baffled cryptographers for over a century.

Her discovery has suddenly made her one of the brightest stars in manuscript studies.

But Macmillan immediately grounds Anya’s brilliance in domestic vulnerability.

Anya’s mother Rose Brown is seriously ill with cancer, and Anya is deeply in love with Sid, her long-term partner.

Job offers pour in—from dream institutions like Yale and MI5’s discreet overtures—yet she’s reluctant to leave the UK or to vanish into secret intelligence work.

This is where the Institute of Manuscript Studies in St Andrews appears, via an email from Professor Diana Cornish, praising Anya’s work on “Folio 9” and inviting her to interview for a uniquely well-funded role in Scotland.

Anya is intrigued, reassured by her mentor Professor Trevelyan that the Institute is “small but elite” and “exceptionally well funded,” though its bare-bones website and absence from student review sites feel like a quiet warning she decides to ignore.

As a reader, you can feel the trap closing even as Anya steps into it with hope.

3.2 The secret war: Kats vs Larks and the hunt for the Book of Wonder

In alternating chapters we’re introduced to Olivia Macdonald, a seemingly conventional judge’s wife and mother of teenage twin boys, whose organised home life—MacBook folders blandly labelled “Family,” “Housekeeping,” “Holidays”—conceals her senior role in the Order of St Katherine.

The Kats are an all-female, aristocratic network that believes women’s power is best wielded indirectly, through husbands and sons, “wives and mothers” pulling strings behind the scenes.

Olivia’s marriage is a textbook example: her husband, Judge Henry Macdonald, is in a long-term affair with Professor Diana Cornish, and Olivia knows every detail, thanks to the nanny cams and encrypted audio software she uses to monitor their London flat.

She accepts the humiliation as part of the Order’s wider strategy—“men will be men; you work with what you have”—so long as it advances the Kats’ agenda.

Opposing the Kats is the Fellowship of the Larks, a more radical, meritocratic network of women who want direct power for women themselves.

If the Kats are Tory grandees in pearls, the Larks are the quietly furious feminist professionals who’ve had enough of waiting.

Both groups are obsessed with The Book of Wonder, a legendary early-modern manuscript associated with women’s knowledge and self-determination.

For the Kats, the book is a relic, “the first link in a centuries-old chain of women working quietly…for the good of society”—a sacred symbol of their ideology.

For the Larks, it’s a tool: proof that women have always shaped history and a bargaining chip that can be used to reshape the future.

The problem is that nobody knows exactly where the Book is.

The Larks believe its location is encoded in the embroidery linked to Eleanor Bruton and in the surviving manuscripts of Magnus Beaufort, a charismatic male collector with a long, messy history with Anya’s mother Rose.

The Kats suspect the same thing and have embedded agents close to both women.

When Anya takes the post at St Andrews, she walks straight into the middle of this secret war.

The Institute itself is effectively a Lark front: its generous funding and obscure mandate exist to support the hunt for the Book of Wonder.

Anya’s rare combination of visual memory and Voynich expertise makes her the perfect person to decode any hidden map or cipher embedded in Magnus Beaufort’s surviving collection and in the embroidery.

Of course, nobody tells her the truth in plain language.

Instead, we watch as she’s nudged, manipulated and lied to by powerful women on both sides, each convinced they alone deserve to wield the book’s power.

3.3 Clio Spicer, the police, and the corruption of institutions

Parallel to Anya’s storyline, Detective Constable Clio Spicer is working a case in the Metropolitan Police’s Art and Antiques Squad.

She’s initially drawn in by suspicious deaths and an odd textile artifact—the same embroidery Eleanor Bruton died for.

Clio’s segments show how deeply the Kats and Larks have infiltrated institutions you’d expect to be neutral: museum boards, police units, banking, academia.

At one point, Clio discovers that her own team is being pulled off a case mid-investigation; her boss simply orders her to stop, no explanation, no transparency, while a senior male officer quietly takes over.

Later, she travels to Italy, breaking minor rules to keep following the trail, and begins to feel “a strong whiff of corruption” without knowing which of her colleagues—or superiors—she can trust.

These chapters are where Macmillan’s background in crime fiction really kicks in.

We see how evidence can be buried, how powerful people lean on institutions, and how a committed officer like Clio is forced into morally dubious decisions to protect vulnerable women like Anya and Rose.

For me, one of the most powerful threads is Clio’s sense of duty: she believes in justice and in protecting people from crime, yet she’s operating inside a system subtly and sometimes overtly bent to serve secret networks.

That moral claustrophobia is as important as any car-chase scene.

3.4 Escalation: arson, murder, and kidnapping

As Anya settles into St Andrews, strange things start to happen.

There’s an arson attack on a lab, pressure from her enigmatic colleague Sarabeth, and a rising body count among women connected to the embroidery and Magnus’s collection.

On the Kats’ side, Olivia receives word that Diana Cornish has been murdered, apparently in a way designed to look like the work of the Order itself.

The implication is chilling: the Larks (or another unknown player) are willing to frame their rivals while closing in on the Book of Wonder.

Olivia’s response is coldly strategic; she worries less about Diana as a person and more about managing the fallout, keeping the Order’s name out of the press and retaining their influence.

Simultaneously, the Kats escalate against Anya by targeting her mother.

We learn that they’ve planted a nurse, Viv, in Rose Brown’s life as both caregiver and spy, monitoring Anya’s visits and emotional vulnerabilities.

When Olivia and her colleagues conclude that Anya might be close to a breakthrough—and that the Larks may have brought her too near to the Book of Wonder—they decide to kidnap Rose, explicitly to use her as leverage.

It’s a turning point: the abstract battle over a manuscript becomes a very concrete threat to a sick woman whose only “crime” is being the mother of a gifted scholar.

On the Lark side, we watch Sarabeth—an anxious, intense academic—step into Diana’s role with an increasingly ruthless mindset.

Her grief hardens into resolve: she thinks that “a clean house meant a strong, efficient house,” and decides that if men like Magnus and Sid are obstacles, they can be “dealt with” permanently.

What begins as a feminist conspiracy thriller starts to look uncomfortably like a critique of how revolutionary movements can mirror the brutality they were founded to resist.

3.5 Verona, Voynich and the map of the city

The last third of The Burning Library shifts the action from Scotland and London to Verona, Italy.

Following clues buried in the embroidery and the Voynich manuscript’s famous rosette page, Anya and Sid travel to the city to see whether the strange diagrams might in fact be a map.

As they walk through Verona—past the amphitheatre, along the Adige, towards the Basilica of San Zeno—Anya begins to notice architectural echoes of the manuscript’s symbols.

She realises that some of the rosettes and shapes might correspond not to stars or an imaginary landscape, but to specific sites in Verona, including San Zeno’s rose window and the outline of the arena.

This is classic dark-academia wish-fulfilment: the idea that if you’re clever and obsessive enough, you can read an entire city like a text and find treasure in its stones.

At the same time, Macmillan keeps the stakes human.

Anya is convinced that if she can get to the Book of Wonder first, she might use it as leverage to protect her mother, and that hope is “the most dangerous emotion” in the book; it drives her to take risks that a more cautious academic never would.

As their enemies close in, Clio races to Verona too, juggling a fragile alliance with Italian police and her fear that Kats or Larks may have infiltrated law enforcement there as well.

The climax centres on a church in Verona, where Anya finally locates the Book of Wonder hidden among old fabrics and liturgical items—a “dusty little volume” whose illuminated pages take her breath away, “the Mona Lisa of manuscripts.”

In a tense confrontation with armed carabinieri, Anya makes a split-second decision: she hands over what appears to be a precious Bestiary (her father’s prized manuscript) while secretly keeping the Book of Wonder concealed in her backpack.

Clio initially panics, thinking Anya has surrendered everything; Sid even believes she has given up Magnus’s bestiary.

But as Anya emerges from the church, soaked, shivering and smiling, Clio spots the rectangular outline in her backpack and realises what Anya has done: she’s fooled both the police and the waiting factions, keeping the true prize for herself.

It’s one of the most satisfying beats in the novel: a young woman using her training, memory and nerve to flip a situation engineered to control her.

3.6 Endgame and resolution (without line-by-line spoilers)

In the final chapters—set partly in a quiet Verona piazza named after the Renaissance humanist Isotta Nogarola, who once defied gendered expectations—Anya, Sid and Clio negotiate what to do with the Book of Wonder and how to protect Rose.

We see partial reckonings inside both the Larks and the Kats, with some women questioning the cost of their methods and others doubling down on brutality.

Macmillan doesn’t offer an easy, utopian ending.

Instead, she leaves us with the sense that the war over women’s stories—who writes them, who archives them, who weaponises them—is far from over.

Anya survives, but she’s no longer naïve.

Clio walks away with scars and a sharper understanding of how fragile institutional integrity really is.

And the Book of Wonder, while no longer lost, refuses to sit obediently in any one group’s hands.

4. The Burning Library Critical Analysis

Evaluation of content – how well does it all work?

From a craft perspective, The Burning Library is ambitious, sometimes to a fault.

Macmillan braids together:

- A campus-novel-style academic arc (Anya’s career and the Institute).

- A procedural crime plot (Clio’s investigation).

- A dual-faction conspiracy thriller (Larks vs Kats, plus Magnus and the collectors).

Reviewers like Publishers Weekly have described it as an “overstuffed Dan Brown riff”—which I think is both fair and a bit reductive.

On the plus side, the book’s world-building is rich and convincing.

Macmillan’s research on manuscripts, provenance, the Voynich, and the practicalities of police procedure shows up in small, telling details—like the way Clio worries about evidence-room access or Anya traces bindings and marginalia for clues.

As a reader, I never doubted that the Institute could exist or that Lark and Kat operatives could plausibly be embedded in banks, universities and law firms.

Even the more flamboyant ideas—the Voynich’s rosette page acting as a map of Verona, for example—are grounded in real-world scholarship, where people have proposed astronomical and geographical readings of that page for decades.

Where some readers (and I, at times) struggled was pacing and density.

The opening introduces a large cast of similar-sounding characters very quickly, which several bloggers have flagged as confusing or slow, and I found myself flipping back to remind myself who belonged to which faction.

There are also moments where the villains’ plans hinge on unlikely coincidences or need a bit of hand-waving to land.

However, the emotional core—Anya’s love for her mother, Clio’s commitment to justice, Olivia’s morally contorted loyalty to the Order—remains strong enough that the story never collapses under its own weight.

In terms of the book’s stated purpose, Macmillan has positioned The Burning Library (in marketing copy and interviews) as dark academia with a “sly feminist twist,” and early blurbs from writers like Shari Lapena and B.A. Paris praise it as “fresh, fun and full of thrills” while tackling “dark obsession and murderous ambition.”

On that score, I’d say the novel succeeds.

It absolutely delivers the page-turning thrills: murders, kidnappings, secret meetings, betrayals, a climactic showdown in a foreign city.

But it also asks more uncomfortable questions about how women’s organisations—whether traditional like the Kats or radical like the Larks—can reproduce the same hierarchies and abuses of power they were created to fight.

Thematically, the book contributes meaningfully to conversations about:

- Violence against women: not just as isolated crimes, but as systemic tools used by networks on all sides.

- The politics of care: how mothers’ bodies and illnesses become bargaining chips, as with Rose.

- Knowledge and gatekeeping: who gets access to archives, jobs, funding, and how “merit” is defined.

These line up uncomfortably well with current reports from UN Women, WHO, and EU agencies about persistent gendered violence and the slow progress of women into genuine positions of power in academia and politics.

From a personal reading perspective, the only place I felt the book falter was in its ending.

Like some reviewers, I found the final revelations a little rushed, with “broad explanations” where earlier chapters had been forensic.

That said, the emotional payoff of Anya’s choices in Verona, and the quiet, complicated peace between her, Clio and Sid, stayed with me long after I closed the book.

5. Reception, criticism and influence

Because The Burning Library is a 2025 release, we’re looking at early reception rather than long-term legacy.

So far, response has been broadly positive but mixed in tone.

On the enthusiastic side, blurbers like Shari Lapena call it “fresh, fun, and full of thrills…dark academia with a sly, feminist twist,” while B.A. Paris praises it as “a beautifully-written story of dark obsession and murderous ambition.”

The Burning Library has also been selected for the LibraryReads Hall of Fame list for November 2025, a significant sign that librarians see Macmillan as a consistent, reader-pleasing author.

Crime and thriller outlets like Crimespree Magazine highlight the novel’s “centuries-old secret” and the ideological conflict between two visions of women’s power, even while noting that the specifics of the Book of Wonder can feel “frustratingly vague.”

Book bloggers have raised more pointed criticisms.

Sites like All The Right Reads and Montana Musings comment on the crowded cast, slow initial pacing and a somewhat rushed ending, with one reviewer giving it 3/5 stars while still calling it “thought-provoking.”

From a more industry-facing perspective, Publishers Weekly notes that Macmillan is pivoting here from her usual psychological-suspense territory into a more Dan-Brown-style conspiracy thriller, and suggests that the novel is “overstuffed” but still propelled by her trademark emotional acuity.

Influence is harder to measure so early, but a couple of trends stand out.

First, The Burning Library is part of a broader wave of library-and-archive-centric fiction—books like Mark Lawrence’s The Book That Wouldn’t Burn or Heather Fawcett’s Emily Wilde series—that treat libraries as sites of both wonder and violence.

Second, the novel contributes to a mini-trend of explicitly feminist secret-society narratives—alongside essays and histories about real women’s clubs and societies, such as the Heterodoxy group in early-20th-century New York, or scholarship on female-only societies that shaped modern feminism.

I couldn’t find any detailed discussion of The Burning Library on your own site, probinism.com, as of now; searches for the title and for Gilly Macmillan returned no direct hits, which suggests this is still fresh territory for critical essays and cross-media exploration there. (I’m being explicit here so you know I checked.)

6. Comparison with similar works

Reading The Burning Library, I kept mentally shelving it alongside three kinds of books.

6.1 Dan Brown–style code thrillers

Structurally, the novel absolutely owes something to Dan Brown: there’s a puzzle-text, a city-as-map, and a race between rival factions to decode symbols before the police catch up.

If you enjoyed The Da Vinci Code or Origin but wished the story cared more about women’s interior lives and the ethics of academia, this feels like a feminist evolution of that template.

Where Brown often leans into grand conspiracies about the Catholic Church and secret male orders, Macmillan turns the spotlight onto women’s parallel networks and asks what it costs them to wield power in systems built to exclude them.

6.2 Dark academia with a crime-fiction spine

Marketing copy positions The Burning Library as “perfect for fans of Alex Michaelides and Ruth Ware,” and that’s broadly accurate in terms of mood: cloistered campuses, secrets among the scholarly elite, morally compromised women trying to survive.

Compared to many dark-academia novels—The Secret History, Babel, or Ninth House—Macmillan’s book is more procedural, less mythic.

She’s less interested in aestheticised decadence and more in institutional rot: police corruption, academic politics, the financial structures behind rare-book collecting.

If you want lush campus melancholy and Greek-chorus narration, you might find The Burning Library a little brisk and external.

If, like me, you enjoy campus books that actually show people doing the work—transcribing, cataloguing, haggling over funding—it’s a refreshing change.

6.3 Feminist thrillers about violence and control

Finally, the novel sits comfortably beside other feminist-leaning thrillers that interrogate violence against women and the networks that enable or resist it.

Macmillan’s earlier works, such as What She Knew and The Nanny, already explored motherhood, class and media pressure; here she scales those concerns up to an international conspiracy.

In the broader landscape, the book resonates with current reporting and commentary about gender-based violence—from UN Women’s figures to UK parliamentary inquiries and high-profile cases discussed in outlets like the BBC and The Guardian, where families of murdered women have explicitly called out misogyny as a driving force.

So while the Larks and Kats are fictional, the social forces they exploit—fear, silence, economic dependence—are painfully real.

7. Conclusion

If you’ve read this far, you already know that The Burning Library is not a minimalist thriller.

It’s layered, sometimes messy, occasionally exasperating—and very much worth your time if you care about the intersection of gender, knowledge and power.

You’ll likely love it if:

- You enjoy dark academia rooted in real research and archives.

- You’re happy juggling multiple timelines and points of view.

- You’re interested in feminist takes on conspiracy fiction and rare-book intrigue.

You might bounce off it if:

- You prefer small-cast, tightly focused psychological thrillers.

- You dislike stories where institutions (police, universities, banks) are portrayed as deeply compromised.

- Slow-burn openings and lore-heavy world-building frustrate you.

For me, the book’s lasting power lies less in its twists than in its questions.

How much violence are we willing to overlook when it’s done in the name of “protecting women”?

What happens when organisations founded to support us become the very structures that control us?

And what would it mean, really, for women to own their own archive—to hold, as Anya briefly does, the Book of Wonder and decide for themselves who gets to read it?

Those are questions that echo well beyond the last page, into real libraries, real courts, and real lives.