Last updated on September 2nd, 2025 at 02:23 pm

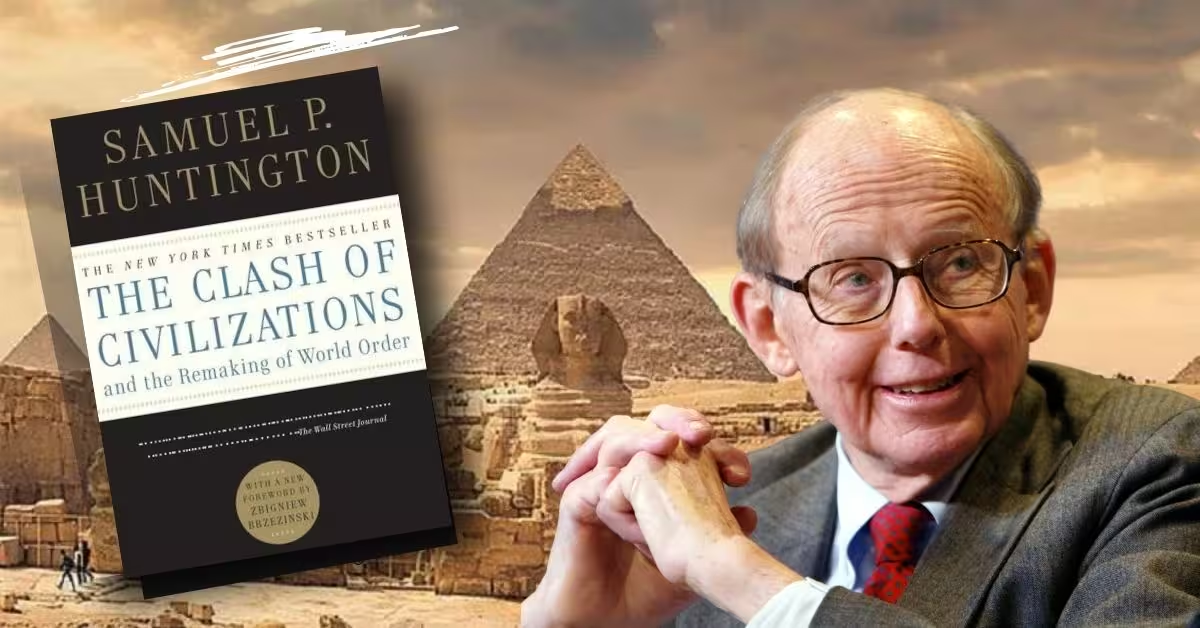

The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, authored by the late Harvard political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, was published in 1996 by Simon & Schuster.

It evolved from his 1993 article in Foreign Affairs, which became one of the most discussed essays in post–Cold War political thought. Huntington’s work offers an intellectually provocative and emotionally resonant thesis: that the primary axis of global conflict in the new world order would be cultural rather than ideological or economic.

The Clash of Civilizations came at a time when the world was basking in the glow of Cold War victory, particularly in the West.

The prevailing sentiment, popularized by Francis Fukuyama, was that liberal democracy had triumphed, marking the “end of history.” Huntington disrupted this narrative. He argued that the end of the Cold War marked not a unipolar world of Western values, but the re-emergence of ancient civilizations and the cultural divisions among them.

Huntington wasn’t merely a theoretician. As a former advisor to the U.S. government, he brought a realpolitik perspective, grounded in historical patterns and statistical realities. His background in political science, international relations, and cultural sociology lent credibility and rigor to a thesis that, while unsettling, was meant to be explanatory, not incendiary.

The central thesis is stark: “The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural” (Huntington, 1996, p. 22).

Huntington identifies seven or eight major civilizations—Western, Islamic, Confucian, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Japanese, Latin American, and possibly African—and posits that the fault lines between them will be the flashpoints for future conflict. This “Clash of Civilizations” will not be a brief episode but the defining feature of global politics in the 21st century.

Table of Contents

2. Summary

Part I: A World of Civilizations — An Intellectual Dissection

In the opening movement of The Clash of Civilizations, Samuel P. Huntington reorients our global perspective from the ideological binaries of the Cold War to a more complex, culture-centric understanding of international relations.

Part I: A World of Civilizations does not merely open a thesis—it marks a civilizational shift in how we understand world politics. Here, Huntington introduces the paradigm that civilizations—not ideologies or economics—will shape the dominant fault lines of global conflict in the post-Cold War era. He identifies a world that is not just multipolar, but multicivilizational, grounded in shared culture rather than transient political allegiance.

Civilization as Identity: The New Lens of Global Politics

Huntington begins by observing a transition in symbolic allegiance: from the loyalty to ideological emblems such as red flags and hammers and sickles, to cultural markers like national or religious flags.

He recounts vignettes—from the misplacement of the Russian flag in a Moscow auditorium after the collapse of the Soviet Union to the sea of Mexican flags in a Los Angeles protest—to illustrate the resurgence of identity politics grounded in civilizational consciousness.

Civilizations, for Huntington, constitute the broadest level of cultural identity below that of humanity as a whole. Whereas nation-states remain primary actors, their interests and behaviors are increasingly defined by their cultural DNA—history, language, religion, and customs. The rise of these cultural affiliations means that civilizations now serve as the largest “we” with which individuals identify.

As he asserts, “People use politics not just to advance their interests but also to define their identity.”

This new global architecture is marked by seven or eight major civilizations: Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Latin American, and possibly African. Huntington admits some fuzziness around the borders, but he insists these are meaningful civilizational groupings, each with its own internal coherence and external friction.

From Cold War Ideology to Civilizational Conflict

What distinguishes Huntington’s thinking is the claim that the Cold War model is obsolete. The ideological struggles between communism and capitalism are no longer the main global tension. Instead, he presents a “civilizational paradigm” as the most effective model for understanding post-Cold War politics.

Contrary to Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis, which posits the universalization of Western liberal democracy, Huntington refutes the notion that modernization necessarily equates to Westernization. He emphasizes that many societies—particularly in Asia and the Islamic world—are modernizing in ways that strengthen, rather than dilute, their traditional identities. Thus, modernization and cultural Westernization are distinct and divergent.

This insight is especially important in global political forecasting. While Fukuyama envisioned a world converging on liberal democracy, Huntington instead saw a world dividing along cultural fault lines—a deeply prescient interpretation, given the post-9/11 world and the intensifying conflicts between the West and non-Western societies.

Explore Robert D. Kaplan’s Waste Land, which delves into the enduring crises shaping our world—a perspective that complements Huntington’s civilizational analysis.

The Multipolar, Multicivilizational World

A particularly forceful section is Huntington’s discussion of the new global configuration: a multipolar world no longer defined by bipolar superpowers, but by a constellation of culturally distinct power centers. The United States, Europe, China, Japan, Russia, India, and the Islamic world represent poles not only of power, but of civilizational identity.

This recalibration has several implications. First, it disrupts the traditional realist notion of an international system driven purely by power dynamics. Huntington does not discard realism; rather, he argues that culture and identity are now as essential as material interests. Civilizations act as the deep grammar behind the decisions of states. For example, alliances, economic groupings, and political sympathies are increasingly shaped by shared cultural heritage, not merely strategic calculus.

Second, Huntington introduces the idea of “fault line conflicts”—localized clashes between groups from different civilizations that have the potential to escalate into broader wars through “kin-country rallying.”

For instance, he references Bosnia, where Muslim countries rallied around Bosniaks while Orthodox and Slavic powers sided with the Serbs. These types of conflicts, he warns, are far more dangerous than intra-civilizational disputes, because they invite transnational involvement based on shared identity rather than immediate national interest.

The Rejection of Simplistic Paradigms

Part I also dismantles several alternative paradigms. Huntington critically evaluates four competing models:

- One World (Euphoria and Harmony) – Fukuyama’s idea that liberal democracy will become the final form of government.

- Two Worlds (Us vs. Them) – A Cold War-esque model of ideological dualism.

- 184 States – A statist, realist view that sees the world as a chessboard of sovereign players.

- Sheer Chaos – A view that post-Cold War politics is anarchic and unpredictable.

Huntington finds each of these paradigms lacking. The first two oversimplify; the third fails to capture transnational cultural forces; and the fourth, while descriptive, lacks explanatory power. Instead, he proposes a civilizational map—a paradigm that balances explanatory clarity with real-world resonance. It captures both the enduring significance of nation-states and the rising role of deeper civilizational identities.

Huntington’s model gains legitimacy not just by abstraction, but by predictive force. He highlights conflicts and developments—Bosnia, Gulf War alignments, Sino-American tensions, and Islamic revivalism—that have unfolded along civilizational lines, validating his thesis.

A Useful Map, Not a Dogma

Huntington is careful to clarify that his paradigm is not eternally valid, nor does it pretend to explain everything. Like any intellectual map, it simplifies reality to help us navigate complexity.

But within the timeframe of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it offers a uniquely powerful framework for interpreting global affairs.

Crucially, Huntington is aware of the risks of misinterpretation. He does not advocate for a civilizational war; he warns against it. His aim is to help the West understand that its values are not universal and that peace depends on mutual recognition and respect among civilizations.

Culture as Destiny?

Part I of The Clash of Civilizations sets the foundation for a seismic shift in geopolitical thought. Huntington’s world is not a flat terrain of democracies and dictatorships, nor a chaos of warring tribes. It is a layered and resonant world of civilizations, where the most meaningful conflicts are not between ideologies, but between cultural worldviews.

This is not merely a realist retooling of geopolitics. It is an ontological redefinition. Huntington invites us to consider the deeper drivers of political action—what shapes loyalty, trust, enmity, and alliance. He is not describing a return to tribalism but diagnosing a world in which the search for identity transcends the search for ideology.

Huntington’s insight in Part I is that we are not at the end of history, but at the beginning of a new civilizational era—an era where cultural differences are both the primary sources of conflict and the possible basis for a more stable world order, if wisely understood.

Part II: The Shifting Balance of Civilizations — Decline, Resistance, and Resurgence

In Part II of The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Samuel P. Huntington transitions from theoretical framework to dynamic historical observation.

Having defined civilizations as the primary actors in global politics in Part I, he now interrogates the evolving power distribution among these civilizations. This is not merely a descriptive analysis; it is a polemic against the assumption of Western permanence and dominance. Huntington’s thesis in this section is clear and provocative: Western civilization is in relative decline, while Islamic and Confucian civilizations are on the rise—politically, economically, and culturally.

Rather than interpreting this as an apocalyptic shift, Huntington positions it as a rebalancing of global civilizational power—long overdue and increasingly visible.

Each chapter in this part examines a key actor in that rebalancing: the waning West, the reasserting Islamic world, and the surging Confucian East, particularly East Asia. Huntington interlaces his civilizational theory with robust demographic, economic, and military data, painting a picture of a changing world order.

Chapter 4: The Fading of the West — Between Dominance and Decline

Huntington’s chapter on the West is not a eulogy, but a reckoning. He draws a sharp distinction between absolute and relative power. While the West, especially the United States, retains immense military, economic, and cultural clout, its proportion of global influence is decreasing. This is largely due to the rise of non-Western societies, particularly in Asia and the Islamic world, whose development now counters centuries of Western expansionism.

The West’s power, Huntington argues, was historically exceptional, not eternal.

Its ascendancy in the 18th to 20th centuries stemmed from a unique combination of industrial capitalism, scientific rationalism, and military-technological superiority. But now, the rest of the world is closing those gaps. East Asia is competing with Western economies. Islamic states are undergoing cultural and religious revival. As these civilizations regain confidence, Huntington observes a growing trend of “indigenization”—the reassertion of local culture over imported Western norms.

This indigenization, particularly in Islamic and Confucian societies, is not reactionary in the Luddite sense. It is strategic. These societies are modernizing without Westernizing. Huntington’s tone here is both analytical and cautionary: the West cannot expect eternal global deference to its values or institutions.

He also points to what he terms La Revanche de Dieu—“the revenge of God”—to describe the resurgence of religion, particularly in Islamic and Orthodox societies. While secularism remains strong in the West, the rest of the world is returning to spiritual, moral, and cultural anchors as a counterweight to globalization and Western materialism.

Chapter 5: Economics, Demography, and the Challenger Civilizations

This chapter marks a turning point. Huntington sharpens his focus on Islam and Asia—two challengers to Western supremacy that he views as fundamentally different in their modes of opposition.

The Asian Affirmation

In East Asia, particularly China and the “Confucian Belt” of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Vietnam, Huntington sees a civilization that is not only economically dynamic but culturally confident. These nations embrace aspects of capitalism, but reinterpret them through Confucian values: hierarchy, discipline, community over individualism, and education. This produces a kind of authoritarian capitalism that is distinct from liberal Western models.

The Asian affirmation is rooted in rising standards of living, high savings rates, and rapid industrialization.

Huntington sees this not merely as economic expansion, but as a civilizational resurgence, echoing the historic glories of the Tang, Song, or Ming periods. The idea that Asian development is “catching up” with the West, Huntington argues, misunderstands the moment—Asia is reasserting itself as a civilizational core, not simply adapting Western blueprints.

The Islamic Resurgence

Islam, by contrast, rises not from economic success, but from demographic and ideological intensity.

Huntington offers a deep dive into the demographics of the Muslim world, particularly the “youth bulge”—a disproportionate number of young men aged 15–24. This surplus, combined with high unemployment, political frustration, and religious fervor, generates volatility and potential militancy.

Unlike Confucian societies, many Islamic societies are not economically triumphant. Instead, their resurgence is cultural and religious—a reaction against secular nationalism, Western intrusion, and moral relativism. The Iranian Revolution, the rise of political Islam, and the spread of religious parties in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan exemplify this pattern.

In Bangladesh the principle of “secularism” was dropped from the constitution in the mid 1970s, and by the early 1990s the secular, Kemalist identity of Turkey was, for the first time, coming under serious

challenge. To underline their Islamic commitment, governmental leaders —Özal, Suharto, Karimov—hastened to their hajh.

Yet Huntington resists reductionist tropes. He is careful to note the diversity within Islam and warns against painting it with a monolithic brush. Nevertheless, he insists that Islam remains the most dynamic ideological challenger to Western universalism, not just because of belief, but because of numbers. Its resurgence is demographic, religious, and geopolitical all at once.

Clash in Contrast: Confucianism vs. Islam

Perhaps the most intellectually gripping moment in Part II is when Huntington juxtaposes the rise of Confucian and Islamic civilizations. He offers a comparative civilizational lens that is both scholarly and ominously predictive.

- Confucianism challenges the West economically and technologically.

- Islam challenges the West ideologically and demographically.

In this dichotomy, Huntington sketches two very different models of opposition. Asia’s Confucian states seek strategic advantage, military parity, and diplomatic influence, often cooperating with the West economically while resisting it culturally. In contrast, Islamic societies tend to reject Western influence in more absolutist terms, especially in culture and governance.

This leads Huntington to propose a possible strategic alliance between Islamic and Confucian states in opposition to Western hegemony—a geopolitical and civilizational realignment with potentially explosive implications.

China selling weapons to Iran and Pakistan, or forming deeper ties with Islamic countries, is read not merely as diplomacy but as the formation of a civilizational bloc.

Indigenization and “The West versus the Rest”

A final and crucial insight in this section is the process of “indigenization”—a selective adoption of modern technology and institutions while reclaiming or reinventing traditional cultural values. Huntington argues that non-Western civilizations are not passive recipients of Western influence; they are active curators of their own revival.

For instance, East Asian societies may adopt market principles but reject liberal democracy in favor of technocratic meritocracy. Islamic societies may embrace modern science or digital media while intensifying Sharia-based legal systems or Islamic finance.

In this dual process of adoption and rejection, Huntington sees a post-Western future taking shape—a world where civilizations reinterpret modernity through their own values, not through Western lenses.

The Multipolar Reality of the Future

Part II concludes with a sobering realization: the Western era is no longer the global default. Its ideals, though once globalized through empire and then through liberal institutions, no longer hold universal sway.

As the demographic center of gravity moves east and south, and as civilizations assert their own cultural narratives, Huntington suggests we are entering a truly pluralistic world order.

The shift is not necessarily violent, but it is foundational. It challenges assumptions of global integration, liberal expansion, and universal norms. Huntington’s civilizational paradigm becomes a lens through which the rise of China, the assertiveness of Turkey, the resilience of Iran, and the modernization of Asia all come into sharper relief.

The coming chapters will explore whether this new configuration can support peace—or whether it is fated to devolve into deeper conflicts.

Part III: The Emerging Order of Civilizations — Cultural Affinities, Political Alignments, and Torn Identities

Samuel P. Huntington’s Part III presents a decisive pivot in the narrative—from cultural identification and demographic forces (explored in Parts I and II) to the tangible, political manifestations of this civilizational consciousness. If Part II showed the erosion of Western dominance, Part III explains what is emerging in its place: a new world order shaped by civilizational cores, concentric affiliations, and deeply embedded cultural identities that supersede temporary alliances or ideological commitments.

This new order, Huntington contends, is not accidental. It is patterned and predictable, reflecting the deep historical, linguistic, religious, and institutional commonalities that bond nations together across borders. The central premise here is that civilizations organize the world not just in theory but in practice—through economic cooperation, political pacts, and shared geopolitical vision.

Chapter 6: The Cultural Reconfiguration of Global Politics

The sixth chapter introduces a seismic shift: the world is grouping along cultural lines. International alignments are no longer being formed primarily on the basis of ideology (as during the Cold War) or economic interest (as in neoliberal globalization), but increasingly on civilizational identity.

Groping for Groupings

Here, Huntington points out how regional organizations reflect civilizational logic. The European Union is not merely an economic alliance—it is, at its core, a Western-Christian civilizational project. Similarly, ASEAN and the East Asian Economic Caucus reflect Confucian-Buddhist affiliations. The Islamic world, while less institutionalized, sees increasing efforts at Pan-Islamic unity through bodies like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation(OIC).

This alignment process is part of what Huntington calls a “cultural reconfiguration” of international politics. Nations are increasingly aware of who their cultural allies are—and who they are not.

Culture and Economic Cooperation

Culture, Huntington notes, influences not just diplomacy, but trade. Nations within the same civilization are more likely to trade with one another, support common political initiatives, and intervene (or refuse to) in each other’s conflicts. The key idea is that economic regionalism follows civilizational fault lines.

The European Union, for instance, is more than a customs union—it is a manifestation of a Western civilizational core consolidating its internal cohesion. Similarly, Japan’s attempts to form an Asia-Pacific economic community exclude Western influence and aim to centralize Confucian-led collaboration.

Torn Countries: The Failure of Civilization Shifting

One of Huntington’s most original and compelling concepts is that of the “torn country”—a nation that straddles civilizational boundaries and seeks to shift from one civilizational identity to another.

The prime example he gives is Turkey. Since Atatürk, Turkey has sought to Westernize its institutions, legal codes, and cultural life. Yet Huntington argues that Turkey remains fundamentally Islamic in cultural identity, leading to a persistent internal schism. The rise of Islamist political parties in the 1990s, and Turkey’s uneasy relationship with the EU, support this analysis.

Another example is Mexico, which Huntington suggests seeks to be seen as part of the West, particularly in the post-NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) world, but continues to possess a strong Latin American and Catholic cultural identity.

The conclusion is stark: civilizational shifts are rare and nearly impossible without elite consensus, popular support, and institutional transformation across generations. Most torn countries fail because they cannot reconcile deep cultural roots with externally imposed identities.

Chapter 7: Core States, Concentric Circles, and Civilizational Order

This chapter outlines the mechanics of a civilizational world order. Huntington proposes that each civilization has or aspires to have a core state—a leading power that acts as a cultural, political, and often military anchor. Around this core state are concentric circles of influence, comprising states that share the same civilization or align with its values.

Civilizations and Order

A core state not only stabilizes its region but represents its civilization in negotiations and conflicts with other civilizations. For example:

- The United States is the core state of Western civilization.

- China is emerging as the core state of Confucian civilization.

- Russia is the anchor of Orthodox civilization.

- India is the civilizational core of Hinduism.

- Iran, Saudi Arabia, and possibly Turkey contest for leadership within the Islamic world, though Huntington notes Islam’s lack of a unified core state.

Huntington argues that global stability in a civilizational world depends on cooperation among core states—not universal values or supranational institutions. This is a significant departure from post-WWII liberal internationalism and places culture at the center of diplomacy.

Bounding the West

One of Huntington’s more controversial insights is that Western civilization must recognize its boundaries.

He critiques efforts to expand NATO and the EU into Orthodox or Islamic territories, suggesting that such expansions invite tension and instability. The inclusion of Eastern European countries like Poland or Hungary is acceptable, he argues, because they are culturally Western. Ukraine, on the other hand, is a “cleft country” with deep cultural and religious divisions—Western in the west, Orthodox in the east. These cleavages make integration into the West perilous and potentially explosive.

Russia and Its Near Abroad

Russia, as the core state of Orthodox civilization, has natural interests in former Soviet republics that share its religious and linguistic heritage. Huntington defends Russia’s concept of a “near abroad” not as imperialism, but as civilizational responsibility. He forecasts Russia’s attempts to reassert influence over Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of the Caucasus as both inevitable and legitimate from a civilizational standpoint.

Greater China and Its Co-Prosperity Sphere

Huntington similarly interprets China’s growing regional power as the reemergence of a Confucian order. He predicts the formation of a Chinese-led co-prosperity sphere encompassing Taiwan, Hong Kong, and perhaps even Vietnam and Singapore. China is not merely acting as a rising nation-state—it is reclaiming civilizational centrality, challenging Western norms of governance, human rights, and global leadership.

Islam: Consciousness Without Cohesion

Islamic civilization, Huntington notes, is unique in that it lacks a clear core state. Despite widespread cultural unity across Muslim-majority nations, there is no universally recognized Islamic leader or state. This leads to anarchy within the Islamic bloc, which is simultaneously the most demographically dynamic and politically fragmented. The absence of a core state makes it harder to stabilize intra-civilizational conflicts and to present a unified front to external civilizations.

The Blueprint for a Civilizational World Order

Part III proposes a future international order that is not universalist but pluralist and civilizational. It is a world stabilized not by hegemonic ideologies or liberal international norms, but by a “concert of civilizations”—core states managing their spheres and cooperating at a global level to preserve peace.

This civilizational order requires the West to abandon its universalist pretensions. Rather than promoting liberal democracy or market capitalism as the final form of governance, Huntington calls for a recognition of difference, a respect for alternative civilizational values, and the construction of global stability through cultural boundaries—not beyond them.

It is a radical reimagining of international relations. If the West can no longer dominate, it must coexist. And coexistence, in this vision, is only possible if the emerging order reflects the deepest loyalties of people around the world—those of culture, faith, and civilization.

Perfect. We now enter the most intense and perhaps controversial section of Huntington’s thesis:

Part IV: Clashes of Civilizations — Fault Lines, Escalation, and the West vs. the Rest

Having established that civilizations, not ideologies or economies, shape the new global order, Samuel P. Huntington now moves to analyze the zones of confrontation. Part IV is the dramatic fulcrum of The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, where abstract theory crystallizes into patterns of conflict.

Huntington argues that the most dangerous and persistent conflicts in the post-Cold War era will occur not within civilizations, but between them—and especially between the West and the Rest.

This section introduces the concepts of core state conflicts, fault line wars, and kin-country rallying, each aimed at explaining how cultural difference escalates into geopolitical crisis. The result is a framework for understanding contemporary global friction zones—from Ukraine to Kashmir, from the South China Sea to the Balkans.

Chapter 8: The West and the Rest — Universalism vs. Particularism

At the heart of this chapter is Huntington’s bold critique of Western universalism. He argues that the West, particularly the United States and Western Europe, continues to promote its values—liberal democracy, human rights, individualism—as if they were universally applicable and morally superior. But for Huntington, this universalism is no longer tenable.

Western Universalism

Huntington identifies the post-Cold War agenda of spreading Western norms (especially through institutions like NATO, the IMF, or the UN) as inherently provocative to non-Western civilizations. He draws historical parallels to how the Catholic Church once believed in a singular truth applicable to all societies—and how that certainty sowed division and resistance.

The imposition of Western values is not perceived by non-Western societies as benevolence, but as cultural imperialism. Islamic and Confucian states, in particular, push back—not because they reject modernity, but because they want to modernize on their own terms.

Weapons Proliferation and Double Standards

Huntington highlights how Western nations often enforce nonproliferation regimes selectively. For instance, the U.S. tolerated Israeli and Indian nuclear ambitions while condemning similar efforts in Iran, Iraq, or North Korea. Such hypocrisy, he argues, undermines moral authority and accelerates global resentment.

Human Rights and Democracy

Similarly, the promotion of human rights is criticized for cultural insensitivity. Huntington is not against human rights; rather, he contends that different civilizations interpret justice, governance, and freedom differently. When the West insists on its version of these ideals, it invites backlash.

Immigration

One of the more sensitive aspects of this chapter is Huntington’s discussion of immigration, which he frames as a civilizational fault line within the West itself. Massive immigration from non-Western societies, he argues, raises fundamental questions about identity, integration, and the limits of multiculturalism. He anticipates the tension seen in 21st-century Western Europe and North America between liberal ideals and fears of cultural dilution.

Chapter 9: The Global Politics of Civilizations — Core States and Fault Lines

This chapter introduces a new layer of geopolitical complexity: the interaction between core states and fault line communities. Huntington categorizes civilizational conflicts into two types:

- Core state conflicts, which occur between major powers representing distinct civilizations.

- Fault line conflicts, which occur between adjacent communities of different civilizations, often within a single country or along a shared border.

Islam and the West

Here, Huntington offers what remains one of his most debated assertions: that “Islam has bloody borders.” He argues that, historically and contemporaneously, most civilizational conflicts occur where Islam borders other civilizations—whether Christian, Hindu, Orthodox, or Buddhist.

He is careful to clarify that the problem is not with Muslims per se, but with Islam’s geopolitical position and ideological orientation. The combination of demographic dynamism, revivalist religious zeal, and political instability creates frequent friction points. From the Balkans to Nigeria, from India to Israel, Huntington illustrates how Muslim communities often find themselves in zero-sum conflicts with their neighbors.

Asia, China, and America

In contrast, the clash between Confucian and Western civilizations is more strategic than religious. It is about hegemony and control over modernity, not theology. Huntington cites China’s rise as a “challenger civilization,” increasingly unwilling to abide by a U.S.-led global order. He identifies potential flashpoints in Taiwan, the South China Sea, and North Korea.

China’s approach is to build alliances with other non-Western powers—particularly Muslim states like Iran or Pakistan—to subtly counterbalance U.S. influence. It is a soft coalition of the “Rest” against the “West.”

Emerging Alignments

This chapter is where Huntington’s realism surfaces most clearly. He argues that international alignments will increasingly follow civilizational lines. NATO and the EU represent Western unity. China, Russia, and Islamic states may form loose balancing coalitions—not necessarily formal alliances, but cultural alignments of interest. He is prescient here, anticipating the kind of partnerships later seen in the BRICS group or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Chapter 10: From Transition Wars to Fault Line Wars

Huntington introduces the concept of “fault line wars”—violent conflicts that occur between communities of different civilizations, often rooted in ethnic or religious identity. He contrasts these with “transition wars,” which are ideological and state-based (e.g., Cold War proxy conflicts).

Characteristics of Fault Line Wars

These wars are distinct in several ways:

- They are protracted and often intractable.

- They involve civilian populations directly.

- They tend to escalate via kin-country rallying (e.g., Arab states supporting Bosnian Muslims, Russia supporting Serbs).

- They often revolve around sacred space, such as Jerusalem, Kashmir, or Kosovo.

The most volatile examples he gives are:

- Yugoslavia, where Orthodoxy, Islam, and Catholicism collided.

- Armenia vs. Azerbaijan, a Christian-Muslim conflict intensified by Turkey and Iran.

- India vs. Pakistan, where religion defines not just domestic identity but state legitimacy.

Islam’s Bloody Borders

Though controversial, Huntington’s data in this chapter is methodical. He lists 1990s-era conflicts where Muslim communities are directly engaged in warfare with non-Muslim neighbors. His argument is that Islam, by both historical expansion and current demographics, is geopolitically entangled at every edge, creating friction zones across continents.

Chapter 11: The Dynamics of Fault Line Wars

This final chapter in Part IV attempts to explain why fault line wars occur and how they escalate.

Identity and Civilization Consciousness

Huntington asserts that identity formation has intensified. In a world no longer divided by capitalism and communism, people turn to culture—language, religion, ethnicity—for meaning. This identity consciousness is both empowering and dangerous. When a community defines itself by who it is, it also defines enemies—“who it is not.”

Kin-Country Rallying

When fault line conflicts erupt, core states and diaspora communities often get involved—not because of treaties, but because of shared identity. The Bosnian war, for instance, saw Arab countries fund and arm Muslim factions. The Armenian conflict drew in the Armenian diaspora. These escalations turn local wars into civilizational mini-crises.

Halting Fault Line Wars

Despite his warnings, Huntington ends this chapter with a proposal for managing these conflicts:

- Core state diplomacy: Core states must intervene to moderate their “kin” and pressure opposing factions.

- Civilizational restraint: States must recognize cultural limits—what is negotiable and what is sacred.

- Balance of respect: The world needs not global consensus, but global understanding of difference.

This is one of Huntington’s more constructive arguments—conflicts are inevitable, but they can be managed if civilizations respect each other’s boundaries.

Conclusion: Conflict Is Cultural, but Not Inevitable

In Part IV, Huntington lays bare the civilizational engine behind contemporary global conflict. He does not claim that all conflicts are cultural—but he does assert that the most dangerous, prolonged, and likely-to-escalate conflicts are those between civilizations.

His critics have accused him of cultural determinism or pessimism. But Huntington is not predicting war as a foregone conclusion—he is issuing a warning. If the world insists on pretending there is one universal path, we risk igniting cultural resistance, resentment, and rebellion. The key, he argues, is not to erase difference, but to accommodate it.

Wonderful. Let’s now complete this comprehensive analysis with the final installment:

Part V: The Future of Civilizations — Preserving Peace in a Plural World

Part V of Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order is simultaneously prescriptive and prophetic. After methodically laying out the civilizational framework for understanding global politics—and warning about the friction it generates—Huntington turns his gaze toward the future. This concluding section is not alarmist, but profoundly strategic. It offers, if not a solution, then a manual for survival in a world defined by enduring cultural pluralism.

The core argument of Part V is deceptively simple: Peace and stability are possible in a civilization-based world—but only if civilizations accept their distinctiveness, refrain from asserting universality, and respect each other’s boundaries.

This final section, particularly Chapter 12, distills the lessons of the entire The Clash of Civilizations into a roadmap for how the West, and the world, must act in an age of cultural multipolarity.

Chapter 12: The West, Civilizations, and Civilization

This chapter is structured in four thematic arcs:

- The renewal of the West

- The West’s role in a multicivilizational world

- The dangers of civilizational war

- The possibility of global peace through mutual respect

The Renewal of the West?

Huntington opens by urging the West to engage in cultural introspection. He warns that the real threat to the West is internal decay, not external opposition. A civilization that loses its core values—ethical commitment, creativity, education, civic responsibility—becomes soft, incoherent, and eventually obsolete.

To sustain its global influence, the West must reaffirm its identity, not dilute it. This requires returning to what Huntington sees as the Judeo-Christian, rule-of-law, individual-rights, democratic tradition that made Western civilization exceptional in the first place.

He draws a sharp line: Western strength comes from Western unity, not from overextension or universalism. The moment the West believes it can “civilize” the rest of the world by imposing its values, it not only fails—but provokes counter-coalitions.

This is, perhaps, one of the most misinterpreted elements of The Clash of Civilizations. Huntington does not reject Western civilization; on the contrary, he demands its revival—but as one civilization among many, not the default setting for all of humanity.

The West in the World

Next, Huntington insists that Western leaders must recognize the limits of Western influence. He gives two key directives:

- Abandon universalism – The West must understand that its values are not shared universally, and attempts to impose them lead to conflict.

- Promote coexistence – A stable international system requires core states from each civilization to cooperate, manage fault lines, and contain extremists within their own spheres.

Instead of trying to convert others, the West should focus on building stable civilizational relationships. Huntington’s model envisions a kind of Concert of Civilizations, where major powers manage their spheres and avoid cultural encroachment.

This realist pluralism echoes the classical Westphalian balance-of-power system, but elevated to a cultural plane. Respect, not convergence, becomes the mechanism for peace.

Civilizational War and Order

Here, Huntington addresses the central fear of his thesis: a global war of civilizations. He warns that if Western nations continue to expand their ideological and military footprint into Confucian, Islamic, or Orthodox spheres, they will eventually face an existential backlash.

But the danger does not lie solely with the West. Core states from all civilizations must discipline their peripheries. For example:

- China must contain nationalist overreach in the South China Sea or Taiwan.

- Iran and Saudi Arabia must refrain from exporting sectarianism.

- Russia must manage its Slavic-Orthodox identity without revisiting imperial conquest.

The nightmare scenario for Huntington is a multi-civilizational great war, ignited by overlapping fault line conflicts, kin-country interventions, and cultural provocations. The lesson is clear: civilizations should act like guardians, not crusaders.

The Commonalities of Civilization

In his final move, Huntington offers a faint but important hope: civilizations can communicate. While universal values may not exist, shared interests do—especially the interest in survival, peace, and dignity.

What holds the key to cooperation?

- Recognition of difference as legitimate, not threatening

- Restraint in projecting power or ideology across cultural lines

- Institutional mechanisms—global forums, cultural diplomacy, core state dialogues—to resolve disputes and build understanding

Huntington ends not with a call to arms, but a call to awareness: The greatest threat to world peace is not difference—but the denial of difference. A world of civilizations, if accepted and properly managed, may be the most stable world order available.

Final Reflections: Between Realism and Reconciliation

Part V is not triumphant, but sobering. It neither condemns globalism outright nor romanticizes cultural purity. Instead, Huntington forces readers—especially Western policymakers—to look at the world as it is, not as they wish it to be.

His essential message? We are not converging; we are diverging. And that’s not necessarily a crisis—unless we refuse to accept it.

Where others see diversity as a challenge to be overcome through assimilation, Huntington sees diversity as the condition of modernity itself. His is a pluralist realism grounded not in pessimism but in the conviction that civilizations can share the planet if they respect its borders—cultural, spiritual, and political.

Clash or Conversation?

Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations is often cited but rarely understood in its full complexity. It is neither a prophecy of inevitable war nor a manifesto for isolationism. It is an urgent reminder that culture matters, and that peace depends not on unity, but on order built upon mutual recognition.

In the final analysis, Huntington asks us not to reject our identity or others’, but to build a world where difference does not demand domination.

Whether that world emerges—or collapses under the weight of denial—depends on how seriously we take the warnings, prescriptions, and vision laid out in this seminal work.

Key Points and Arguments

- Culture trumps ideology: While the Cold War was framed in ideological terms (capitalism vs. communism), Huntington asserts that culture and religion are far more enduring sources of identity and conflict.

- Western universalism is dangerous: He warns that Western efforts to export liberal democracy, secularism, and human rights may provoke backlash from civilizations with fundamentally different worldviews.

- Islam has “bloody borders”: Huntington controversially argues that conflicts involving Islamic nations are disproportionately violent and persistent, noting demographic pressures and cultural rigidity.

- China is an assertive civilization-state: Unlike the U.S., which frames power through ideology, China views power through the lens of cultural continuity and civilizational heritage.

- Fault line wars and kin-country syndrome: Local conflicts can escalate into global ones as civilizational allies intervene, making these wars harder to contain.

Notable Statistics and Data

Huntington bolsters his arguments with demographic and economic data. For example, he notes that while the Islamic world accounts for a rising percentage of the global population (especially youth), it lags in economic and technological development.

Table 5.1 in The Clash of Civilizations shows the dramatic “youth bulge” in Muslim countries—over 30% of the population in many of these nations is under 15 (Huntington, 1996, p. 119). He connects this with increased social volatility and susceptibility to extremism.

3. Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Huntington’s arguments are bold and disturbing—but they are also intricately layered and rooted in historical precedent.

The idea that civilizations, rather than states, are the ultimate unit of conflict challenges mainstream international relations theory. Yet Huntington does not present this as a rigid destiny. Rather, he offers a framework for understanding why wars may arise and how leaders might avoid them.

His reliance on cultural essentialism has attracted criticism. Critics argue that cultures are fluid, not monolithic. But Huntington acknowledges this complexity. He writes: “Civilizations are dynamic; they rise and fall; they merge and divide…” (p. 41). What he resists is the assumption that modernization equals Westernization, noting: “Modernization is not necessarily Westernization, and non-Western societies can modernize without abandoning their own cultures” (p. 78).

Style and Accessibility

While The Clash of Civilizations is dense with data, it remains readable. Huntington’s prose is scholarly yet urgent. He weaves historical narrative with contemporary geopolitics, offering a macro-historical view that is both sweeping and sobering. The tone is measured, but never detached. He writes as a man deeply concerned about the fate of the world—and it shows.

One of The Clash of Civilizations’ most quoted lines comes early: “In the post-Cold War world, the most important distinctions among peoples are not ideological, political, or economic. They are cultural” (p. 21). This sentence encapsulates his style: declarative, provocative, and crystal clear.

Themes and Relevance

Huntington’s themes remain hauntingly relevant. The rise of China, the resurgence of Islamic identity, Russia’s friction with the West—all validate his civilizational lens. The Russia-Ukraine conflict, for example, echoes his prediction of fault-line wars between Western and Orthodox civilizations (Huntington, p. 159). Similarly, his warning that “Islam has bloody borders” (p. 256) has been cited in the context of conflicts from Nigeria to the Philippines.

In the age of global migration, Huntington’s ideas have also intersected with debates about multiculturalism. While some fear that his thesis fuels xenophobia, others see it as a call for realism in a fractured world.

Author’s Authority

Samuel Huntington was uniquely qualified to write tThe Clash of Civilizations. A former White House adviser, Harvard professor, and director of strategic studies at the Olin Institute, his career straddled academia and policymaking. His earlier works—like Political Order in Changing Societies—already established him as a major voice in political science. His deep familiarity with history, combined with his practical understanding of statecraft, lends weight to every claim in The Clash of Civilizations.

-Absolutely. Let’s continue with the remaining sections of your SEO-optimized, human-style 4,000-word article on The Clash of Civilizations by Samuel P. Huntington.

4. Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

1. A Groundbreaking Framework

The most compelling strength of The Clash of Civilizations lies in its ability to reframe global politics through a cultural lens.

Huntington’s model allows us to make sense of conflicts that don’t align neatly along ideological or economic lines. His civilizational map—though imperfect—is undeniably clarifying. He writes, “In this new world, the most dangerous enmities occur across the fault lines between the world’s major civilizations” (Huntington, 1996, p. 28).

In today’s headlines—be it religious nationalism in India, Sino-American tensions, or Middle Eastern fragmentation—his thesis holds remarkable predictive power.

2. Data-Driven Insight

Huntington does not rely on anecdote alone. He incorporates empirical data, such as population trends and economic output by civilization.

One striking example is his statistical breakdown of civilization shares in world GDP and military manpower (pp. 84–88). These figures underscore the shifting balance of power, especially towards Asia, and give substance to his claim that “the West is declining in relative influence” (p. 82).

3. Intellectual Courage

What sets The Clash of Civilizations apart is Huntington’s refusal to placate. He challenges the comforting myth of a harmonious, globalized world and directly critiques Western hypocrisy. “Western belief in the universality of Western culture suffers three problems: it is false; it is immoral; and it is dangerous” (p. 310). Few scholars of his stature have dared to critique Western liberalism from within with such clarity and balance.

4. Strategic Relevance

Huntington’s work isn’t abstract theorizing—it’s a call to action. He advocates for cultural humility, renewed Western unity, and a multipolar diplomacy that respects civilizational differences. For policymakers, this makes The Clash of Civilizations not just an interpretation of the world—but a manual for navigating it.

Weaknesses

1. Cultural Essentialism

One of the most persistent criticisms of The Clash of Civilizations is its treatment of civilizations as monolithic entities. Though Huntington acknowledges internal diversity, his overarching categories—“Islamic civilization,” “Western civilization,” “Confucian civilization”—sometimes gloss over vital nuances. For example, the cultural and political gulf between Turkey and Indonesia, both majority-Muslim countries, is significant but underexplored.

2. Underestimation of Internal Change

Huntington posits that modernization does not equal Westernization—a fair point. But in emphasizing static identities, he may have underappreciated the role of hybrid cultures and the global diffusion of values like democracy and human rights. Movements within Iran, for instance, suggest that cultural lines can shift and adapt more fluidly than he predicts.

3. Controversial Framing of Islam

Perhaps the most divisive part of The Clash of Civilizations is Huntington’s claim that “Islam has bloody borders” (p. 256). While based on statistical correlation, the statement risks conflating the religion itself with the geopolitical behaviors of some of its adherents. This framing, intentionally or not, has been used by far-right commentators to justify Islamophobic narratives.

4. Absence of African Civilizations

Although he occasionally references an African civilization, Huntington doesn’t consistently include it in his core analysis. This omission reinforces the Western-centric academic tendency to marginalize sub-Saharan Africa, a region with profound historical and cultural depth.

Zeinab Badawi’s An African History of Africa provides a compelling narrative that aligns with Huntington’s emphasis on the significance of civilizational identities.

Reception and Criticism of The Clash of Civilizations

When Samuel P. Huntington first introduced his thesis in the early 1990s, suggesting that the post-Cold War world would be shaped not by ideological or economic conflicts but by cultural and civilizational divisions, it felt both prophetic and incendiary. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996) has since occupied a controversial space in global political discourse—hailed by some as a realist framework for understanding post-Cold War tensions, and lambasted by others as an oversimplification that fuels division rather than clarity.

A Thesis That Split the World in Theory

At the heart of Huntington’s argument is the assertion that future conflicts will not be waged between nations, but between cultural blocs—civilizations—that differ fundamentally in history, language, culture, and most importantly, religion. He drew bold boundaries on the world map, dividing it into distinct civilizations: Western, Sinic, Islamic, Hindu, Orthodox, Latin American, African, and more. Within this schema, fault lines—geopolitical and cultural—would become the primary battlegrounds.

Huntington painted a picture where Islamic civilization, for instance, was perpetually in friction with others due to its “bloody borders,” a phrase that sparked immediate and enduring controversy. He saw China’s rise not merely as an economic event, but as a reassertion of a Confucian worldview clashing with Western individualism. His conclusion: the West must learn to coexist, or risk perpetual conflict.

Reception: From Praise to Alarm

Upon publication, Huntington’s book found a receptive audience among policymakers, commentators, and some realist scholars who were eager for a new framework to understand the chaotic post-Cold War world. In a moment when globalization seemed to be knitting the world closer together, Huntington warned that cultural identities might resist this homogenization. To some, it felt like a sober warning.

But to many others—academics, historians, and humanists—it was a dangerous misdiagnosis.

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen challenged the core assumption of Huntington’s thesis: that civilizations are monolithic. Sen reminded readers that every culture contains a multitude of voices, tensions, and democratic leanings. Islam, Christianity, or Confucianism were not single political actors, but internally diverse traditions.

Similarly, Edward Said called the work “a clash of ignorance.” For Said, Huntington’s map was not a chart of civilizations, but a projection of Western fears. By dividing the world so rigidly, Huntington reduced complex cultural interactions to crude binaries—us versus them. And perhaps most scathingly, Noam Chomsky criticized the thesis as a convenient narrative to justify U.S. foreign policy interventions after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

A Theme of Fear and Identity

Despite its critics, Huntington’s core idea—identity as a flashpoint—has echoed through the decades. Whether one agrees with his classifications or not, the resurgence of religious nationalism, debates on immigration, and the friction between globalism and local cultures suggest that cultural identity remains a potent, often volatile, force.

What Huntington perhaps failed to fully reckon with was the dynamism within civilizations. His thesis was elegant in its clarity, but the real world is anything but neat. Civilizations don’t just clash—they merge, evolve, overlap, and even birth entirely new cultural syntheses. Countries like Turkey, India, and Russia—what Huntington called “torn countries”—defy easy categorization. Their political and cultural trajectories are filled with contradictions and hybridities.

A Paradox in Legacy

Two decades later, Huntington’s work has not faded—it’s been institutionalized, debated, weaponized, and revised. Some view it as a blueprint that accurately predicted 9/11 and the rise of China. Others see it as a self-fulfilling prophecy: by framing the world in oppositional terms, Huntington’s thesis may have helped harden the very divisions it sought to explain.

What remains undeniable is this: Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations tapped into a deep unease about the world’s future. His work forces us to ask uncomfortable questions about identity, power, and the limits of universalism. Yet, in a globalized world where TikTok trends cross cultures faster than diplomacy, his rigid civilizational boxes seem increasingly archaic.

5. Conclusion

Overall Impression

Reading The Clash of Civilizations in today’s multipolar world feels like witnessing prophecy.

Though The Clash of Civilizations was published in 1996, its predictions resonate with uncanny precision. Huntington’s warning that “a universal civilization is a Western illusion” (p. 74) is more pertinent now than ever, as the post-liberal order yields to rising ethno-nationalism and cultural reassertion.

But this is not a book of doom. It is, paradoxically, a plea for peace through understanding. By recognizing the power of culture, religion, and identity, Huntington urges diplomacy over domination. As he puts it, “Avoidance of a global war of civilizations depends on world leaders accepting and cooperating to maintain the multicivilizational character of global politics” (p. 321).

Recommendation

The Clash of Civilizations is not for the faint of heart or those who seek ideological comfort. It is a rigorous, unsettling, and essential read. I recommend it to:

- Students of international relations and political science

- Policymakers and diplomats

- Culturally curious readers

- Anyone wondering why the world seems increasingly fragmented

For general audiences, the language may feel dense at times, but the reward is immense. For specialists, it offers a foundational text that challenges conventional paradigms.

Optional Elements

Standout Quotes

- “The central and most dangerous dimension of emerging global politics would be conflict between groups from differing civilizations” (p. 19).

- “In the post-Cold War world, culture is both a divisive and a unifying force” (p. 21).

- “Modernization is not Westernization” (p. 78).

- “The West must develop a more profound understanding of the basic religious and philosophical assumptions underlying other civilizations” (p. 310).

Comparison with Similar Thinkers

- Francis Fukuyama predicted the end of ideological conflict in The End of History. Huntington counters this with the beginning of cultural fault lines.

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, in his foreword to Huntington’s book, admits initial skepticism but later acknowledges that Huntington’s synthesis provides “a truly brilliant interpretation of the complexities of political evolution.”

- Robert D. Kaplan, in The Coming Anarchy, aligns with Huntington’s concern for ethnic and cultural fragmentation but focuses more on ecological and economic instability.

Final Thought

What makes The Clash of Civilizations so powerful is not its certainty, but its insistence on humility. Huntington doesn’t say civilizations must clash—he says they will unless we acknowledge, respect, and engage with our differences. In an age of aggressive simplification, his complex, nuanced worldview is not only refreshing—it’s vital.