The Diary of a Young Girl is a diary spans from June 14, 1942, to August 1, 1944, written by Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl hiding in Nazi-occupied Netherlands. It is not just a book—it is a voice preserved against silence, a testimony to a life lived in shadow, and a piercing reflection on the horror and hope coexisting during humanity’s darkest hour.

Originally penned in Dutch and titled Het Achterhuis (“The Secret Annex”), the diary was first published in 1947 by Contact Publishing in Amsterdam, later reaching global audiences with its English edition in 1952 under the title Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl.

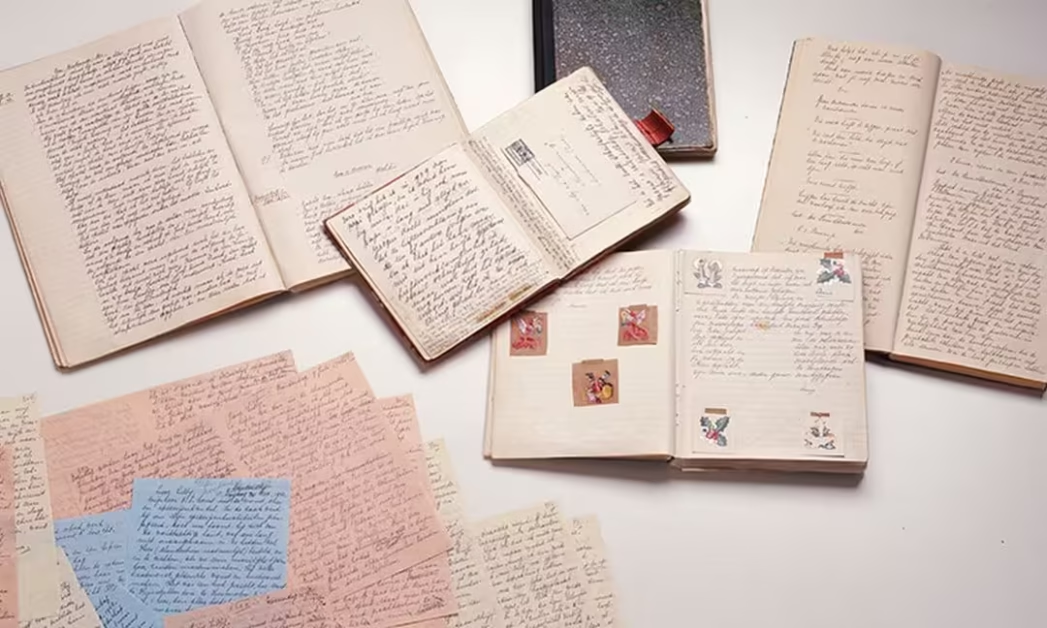

Otto Frank, Anne’s father and the sole survivor of the family, compiled and edited the manuscript from Anne’s original diary and revised notes into a unified text—what came to be known as the “C” version. Anne’s wish, penned in her own words after hearing a radio call for ordinary people to document wartime experiences, was unmistakable: “I want to go on living even after my death!”.

Table of Contents

Background of The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

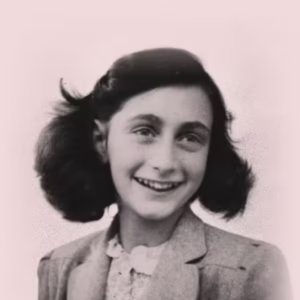

When Anne Frank received a small checkered diary for her 13th birthday on June 12, 1942, it seemed like nothing more than a thoughtful present. She had picked it out herself a day earlier at a local bookstore in Amsterdam, unaware that it would become a window into one of the darkest chapters in human history. The Diary of a Young Girl is more than a simple journal; it is a hauntingly honest document that humanizes the statistics of the Holocaust, giving voice to a young girl whose only crime was her identity.

The background of Anne Frank’s diary is tightly interwoven with the rise of Adolf Hitler, the spread of Nazism, and the brutal realities of World War II.

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, Anne was part of a liberal Jewish family. As Hitler rose to power in 1933 and antisemitic laws proliferated, the Frank family fled to Amsterdam, hoping the Netherlands would offer them refuge. But their hope was short-lived.

In May 1940, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, and with their arrival came an onslaught of anti-Jewish measures: Jewish businesses were shuttered, civil rights revoked, and families like the Franks found themselves systematically isolated.

By 1941, Anne and her older sister Margot were forced to attend an all-Jewish school. The walls of oppression were closing in, and by July 1942, when Margot received a call-up notice for a German labor camp, the Frank family knew they could not wait any longer.

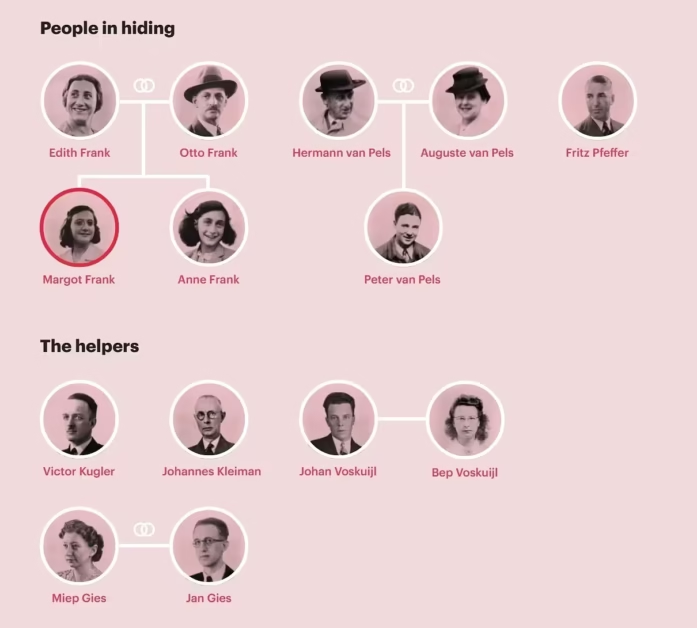

On July 6, 1942, the Franks went into hiding. Their sanctuary was a sealed-off annex behind Otto Frank’s business premises—what Anne would later call the “Secret Annex.” The entrance was ingeniously concealed behind a moveable bookcase. In this confined, claustrophobic space, the family lived alongside four other Jews: the van Pels family (referred to as the Van Daans in the diary) and Fritz Pfeffer (called Albert Dussel by Anne). The tension, the fear, and the sheer monotony of life in hiding shaped Anne’s emotional and intellectual development in extraordinary ways.

Anne’s diary, affectionately addressed to an imaginary confidante she named “Kitty,” began as a form of adolescent expression but soon evolved into a deeply reflective and articulate narrative.

It documents not only the external constraints imposed by the Holocaust but the interior life of a teenager navigating family tensions, romantic feelings, intellectual curiosity, and dreams of becoming a writer.

The diary is filled with vivid snapshots of annex life: the whispering footsteps, the arguments over food rations, and the lingering fear of discovery. Yet, amid these entries, Anne’s voice remains surprisingly hopeful. She famously wrote, “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.” This line, written in the heart of Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, has echoed through history as a symbol of resilience.

But The Diary of a Young Girl is not just a testimony of courage; it’s also a coming-of-age story. Anne candidly wrote about her evolving body, her conflicted relationship with her mother, her admiration for her father, and her complicated friendship-turned-romance with Peter van Pels. Her observations were raw, sometimes harsh, and always honest. She hoped that one day her writings would be more than a private monologue—they would be read by others, perhaps even published.

That hope was tragically fulfilled. On August 4, 1944, the annex was raided by the Gestapo, tipped off either by betrayal or an incidental investigation. Anne, along with the others in hiding, was arrested and eventually deported. She died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in early 1945, just weeks before the camp was liberated. Only Otto Frank, Anne’s father, survived.

After the war, Otto returned to Amsterdam and was given Anne’s preserved writings by Miep Gies, one of the helpers who had risked her life to bring food and news to the annex.

Moved by Anne’s words and determined to fulfill her wish of becoming a writer, Otto compiled her diary into a publishable manuscript. The original red-and-white diary became known as version A; Anne’s revised version, rewritten with an eye toward publication, became version B. Otto’s final edited compilation, version C, was first published in Dutch in 1947 under the title Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex). The English translation, The Diary of a Young Girl, was released in 1952 and rapidly gained worldwide acclaim.

Over the decades, Anne Frank’s diary has been translated into more than 70 languages and adapted for stage and screen.

It has become a cornerstone of Holocaust education and a profound work of Jewish literature. The diary doesn’t simply recount events—it captures a human soul under pressure, one that never lost its dignity or its voice, even in the face of annihilation.

Synopsis: The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl is not just a record of adolescence—it is one of the most intimate and poignant testimonies to emerge from the horrors of the Holocaust. Written between June 1942 and August 1944, this diary offers not only a haunting chronicle of life in hiding but also a rich internal dialogue from a girl in the process of becoming a writer, a thinker, and, painfully, an adult under the most harrowing circumstances imaginable.

A Childhood Interrupted

The diary begins on Anne’s thirteenth birthday, June 12, 1942, when she receives the now-famous red-and-white checkered notebook. “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone,” she writes to her imaginary confidante, Kitty. These early entries are filled with the typical concerns of a teenage girl: school, boys, and friendships, reflecting Anne’s relatively carefree life before the Nazi occupation changed everything.

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, Anne moved to Amsterdam with her family in 1933 to escape Nazi persecution. However, the German invasion of the Netherlands in 1940 soon placed Jews in peril again.

Anne’s diary abruptly shifts from observations about adolescent life to an account of impending terror when her sister Margot receives a call-up notice from the SS in July 1942. “A call-up: everyone knows what that means,” Anne writes with dread, “Visions of concentration camps and lonely cells raced through my head”.

Into Hiding: The Secret Annex

The Frank family quickly went into hiding in the now-infamous Secret Annex, a concealed part of her father’s office building.

The secrecy and danger surrounding their escape is made harrowingly clear: “We were wrapped in so many layers of clothes it looked as if we were going off to spend the night in a refrigerator,” Anne recalled, a necessity since Jews could not be seen carrying luggage.

Once hidden, Anne begins to document life in confinement with unsettling detail. The Annex eventually shelters eight people: the Frank family, the van Pels (van Daan in the diary), and later, Fritz Pfeffer (called Albert Dussel by Anne). Space is tight, privacy is virtually nonexistent, and tensions often erupt into verbal battles.

Anne’s observations of their behavior are astute and unsparing. She often clashed with the adults, particularly her mother: “I feel myself drifting further away from Mother and Margot. I worked hard today and they praised me, only to start picking on me again five minutes later”.

The Banality and Terror of Hidden Life

Anne’s writing captures the surreal blend of boredom and fear that dominates life in hiding. The group had to remain silent during the day to avoid being heard by workers in the building. “It’s the silence that makes me so nervous during the evenings and nights,” Anne writes. “We’ve forbidden Margot to cough at night, even though she has a bad cold”.

Despite this, Anne tries to maintain a semblance of normalcy. She continues her education with great diligence, reflecting an intellectual hunger beyond her years. “I’m crazy about reading and books. I adore the history of the arts, especially when it concerns writers, poets and painters,” she shares. The diary is filled with aspirations: Anne dreams of becoming a writer or journalist, “I want to go on living even after my death!” she exclaims, with remarkable prescience.

The constraints of confinement also heighten her psychological introspection.

Anne identifies a duality within herself—the cheerful, witty girl everyone sees and the contemplative, sensitive soul she often hides. “ I’m afraid that people who know me as I usually am will discover I have another side, a better and finer side. I’m afraid they’ll mock me, think I’m ridiculous and sentimental and not take me seriously….the quiet Anne reacts in just the opposite way,” she confesses in one of the diary’s most powerful passages.

Love and Longing in the Annex

As the months drag on in the Secret Annex, Anne Frank undergoes a profound emotional transformation. Her diary becomes not just a refuge, but a mirror—reflecting her deepest anxieties, intellectual cravings, and blossoming self-awareness. Central to this phase is her evolving relationship with Peter van Daan (real name: Peter van Pels), the son of the other family in hiding.

In early entries, Anne dismisses Peter as shy, awkward, and dull. “He’s a hypersensitive and lazy boy who lies around on his bed all day,” she wrote dismissively.

But over time, their shared isolation draws them together. The loneliness they both feel becomes the soil in which affection unexpectedly begins to grow. In her entry on April 1, 1944, she reveals: “I think about Peter often, and I’d like to get to know him better”.

Eventually, Anne begins visiting Peter in his attic room, and the two share private, heartfelt conversations.

There is a moment of adolescent intimacy when they kiss for the first time—an act that awakens in Anne both a new sense of maturity and a rush of confusion. “When I had to go, he put his arm around me and kissed me on the cheek. I could hardly believe it was true,” she confides to Kitty. But this romance, while tender, is also complex. Anne is acutely aware that their relationship may be a product of shared circumstances rather than real compatibility.

In one especially perceptive reflection, she notes: “He’s adorable, but so lacking in strength. If only I could help him become stronger, braver, more independent”.

Tension, Frustration, and Resilience

Daily life in the Annex is full of petty grievances and magnified emotions. The claustrophobia of the hideout, coupled with constant fear of discovery, often leads to tensions between its inhabitants.

Anne frequently describes conflicts with Mrs. van Daan, whom she sees as vain, meddling, and dramatic. Her sarcasm is often unfiltered: “She’s got the worst nature of anyone I’ve ever met,” Anne notes, “selfish and egotistical”.

Anne’s relationship with her mother remains especially strained. She feels deeply misunderstood and unfairly criticized. “I have to do everything by myself! Mother and Margot always help each other, but I’m left to do the dirty work,” she laments. The disconnection runs deep, and at one point Anne even writes, “I love her because she’s my mother, but I don’t like her one bit”. Only with her father does she feel truly safe and understood, referring to Otto Frank as “the one I cling to”.

Despite the unrelenting boredom and growing tensions, Anne’s mental resilience remains extraordinary.

She never allows the cramped physical space to limit her intellectual or emotional growth. She dives into self-study, reading works of philosophy, literature, and history, showing remarkable curiosity for a girl her age. “I must uphold my ideals,” she writes defiantly, “for perhaps the day will come when I shall be able to realize them”.

War on the Doorstep

As the diary progresses into 1944, the outside world draws closer to the Annex, and the fear intensifies.

Bombings become more frequent, and Anne writes of trembling in bed as sirens wail. News from the radio and the Dutch resistance leaks in through their helpers, and Anne becomes increasingly attuned to the political landscape. The landings in Normandy, the Allied advances—each glimmer of hope is met with desperate optimism in the Annex.

Yet, she remains brutally honest about the horror still reigning outside. The diary details their horror at stories of death camps, starvation, and betrayals. Anne’s growing understanding of her Jewish identity and its implications reaches painful clarity. “Who has inflicted this on us? Who has set us apart from all the rest?” she writes. “We’re Jews, and we always shall be, and because we’re Jews, we’ll always be chased”.

There is a sobering passage where Anne wonders whether it’s still possible to believe in human goodness. Despite all the terror and betrayal, she asserts: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. This line has since become one of the most quoted, and most debated, in Holocaust literature—spoken not from a position of naivety, but from a fierce refusal to surrender her humanity.

The End of the Diary

The diary ends on August 1, 1944. In her final entry, Anne reflects not on fear or politics, but on the duality of her own nature—her outer frivolous self and her inner, more serious soul. “I get cross, then sad, and finally end up turning my heart inside out, the bad part on the outside and the good part on the inside,” she writes. “And I keep trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be if … if only there were no other people in the world”.

Just three days later, the Secret Annex was raided by the Gestapo.

The diary ends in mid-thought—not with closure, but with interruption. Anne, her family, and the others in hiding were betrayed and arrested. They were sent to Westerbork, then to Auschwitz. Anne and her sister Margot eventually died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen in early 1945, just weeks before the camp was liberated. Otto Frank was the only survivor among the eight.

Discovery, Deportation, and Silence

On August 4, 1944, Anne Frank’s worst fears came true. The Secret Annex was betrayed—most likely anonymously—and raided by the Gestapo. All eight inhabitants were arrested and eventually deported to Westerbork transit camp. From there, they were sent to Auschwitz. The last pages of Anne’s diary—so full of introspection, growth, and literary promise—stop abruptly, frozen in time, like the life they documented.

Anne, along with her sister Margot, was later transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where both girls perished of typhus in early March 1945, just weeks before the camp’s liberation by British forces. She was fifteen. Her mother, Edith, died in Auschwitz. Only her father, Otto Frank, survived. Upon returning to Amsterdam, Miep Gies—one of the heroic office workers who had risked everything to shelter the families—gave Otto Anne’s preserved diary pages, which she had found scattered on the Annex floor after the arrest.

Otto Frank, shattered and alone, later wrote: “It took me a very long time before I could read it. And I must say, I was very much surprised by the deep thoughts Anne had, the seriousness, especially for such a young girl.”

The Diary Becomes a Voice for Millions

Anne had written not just for herself, but with a vision for publication.

Inspired by a 1944 radio broadcast in which a Dutch official in exile called for people to keep wartime records for post-war reconstruction, Anne began editing her entries—making revisions, eliminating trivialities, and sharpening her reflections. “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you,” she wrote in her first entry to Kitty, “as I have never been able to confide in anyone”. Her hope was not in vain.

The diary was first published in 1947, under the title Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex), and later translated into dozens of languages.

In 1952, it was published in English as The Diary of a Young Girl, and it rapidly gained global acclaim—not merely as a Holocaust document, but as a work of profound literary, philosophical, and emotional power.

What makes Anne’s diary extraordinary is not only its historical value, but the clarity with which she thinks and writes. She is self-critical, warm, intelligent, and often startlingly insightful about politics, identity, and the psychology of confinement. Even when the terror of the Nazi regime presses most closely upon her, Anne refuses to let her moral clarity be clouded.

She captures her existential dilemma with poignant precision: “I see the world being slowly turned into a wilderness. I hear the ever-approaching thunder, which will destroy us too. I can feel the suffering of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right”.

A Human Voice Amid Inhumanity

There is a remarkable sense of honesty in Anne’s writing that transcends her years. She does not romanticize her situation, nor does she shy away from critiquing those around her.

Her ability to blend observation with empathy is rare, especially under such psychological and physical strain. She was aware of her personal transformation: “I’ve grown closer to Father, who loves me. With Mother it’s just the opposite”, she writes, capturing a tension that haunts her entries but also serves as evidence of her deepening self-awareness.

Anne struggled not only with fear and frustration, but with her own identity. She yearned to be taken seriously—not just as a daughter or child, but as a writer.

And she worked at it relentlessly. “I want to write, but more than that, I want to bring out all kinds of things that lie buried deep in my heart,” she wrote. It’s this desire—this moral and intellectual hunger—that makes her diary such a universal text. It is not a mere chronicle of persecution, but the spiritual autobiography of a girl trying to stay human in a world that had lost its humanity.

Anne’s words remain astonishing not only for their courage, but for their clarity. Her insight into the structural, systematic evil around her was profound. And yet she never relinquished her belief in personal accountability, or in the possibility of a better world. She once confessed, “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world”.

Legacy and Relevance

Anne Frank’s diary is often categorized as a “coming-of-age story,” but such a label, while not inaccurate, is insufficient. It is a document of conscience, a testament of resistance—not in the form of arms, but through unyielding observation, honesty, and faith in truth.

It is also an enduring reminder of what happens when hatred, bureaucracy, and silence converge. Her legacy—perpetuated by schools, memorials, stage plays, and films—is a solemn plea for remembrance and vigilance. The diary teaches not just about the past but demands something of the present: moral clarity, empathy, and resistance against injustice in all its forms.

Anne Frank did not live to become a journalist or writer as she dreamed, but her diary has moved millions, crossed boundaries of religion and nation, and remains one of the most widely read and taught books of the twentieth century. Through the voice of a teenage girl, the horrors of a global atrocity became deeply personal—and thus unforgettable.

As readers, we are left with her voice, suspended in time, still asking questions that matter. “I don’t think of all the misery,” she wrote, “but of the beauty that still remains”.

And that, perhaps, is Anne Frank’s final triumph: she preserved not only her innocence but her hope—and, in doing so, gave it to the world.

Setting

Anne Frank’s diary begins on Sunday, June 14, 1942, during World War II. At this time, 13-year-old Anne and her family live in Amsterdam, where she attends the Montessori School.

As the Nazis march into the Netherlands, they force Jews to wear identifying badges displaying the Star of David. Shortly thereafter, the Jews begin receiving ‘call-up notices’ and are sent to concentration camps. When Margot, Anne’s sister, is told to report to SS Headquarters, her father realizes that the family must hide and arranges for them to stay at the ‘Secret Annexe’ of the warehouse on Prinsengracht Street.

The three-storey building faces a canal that is constantly patrolled by the Nazis. The first floor is a warehouse, the second floor consists of offices, and the third floor serves as a storeroom. The storeroom contains several attic rooms not visible from the street.

A sliding bookcase at the bottom of the staircase separates the offices from the confined area, where the Franks hide with the Van Daan family and the dentist Mr Dussel. It is in this setting that Anne’s story unfolds.

Themes And Characters

Mr and Mrs Frank and their teenage daughters Anne and Margot, Mr and Mrs Van Daan and their teenage son Peter, and Mr Dussel all share the cramped space of the attic refuge. Other important characters are the Dutch people—Elli, Miep, Mr Kraler, and Mr Koophuis—who risk their own lives to hide the Jews and bring them food.

In her diary, Anne reveals herself as an active, playful tomboy, who at first feels that nothing she does is right. By its conclusion, she has developed maturity and confidence. Uprooted from her home and friends, Anne experiences a nightmarish ordeal, constantly facing the threat of the concentration camps and death.

In this tense situation, Anne is constantly surrounded by the same adults, with whom she has frequent conflicts.

She favours her father’s company over that of her mother. ‘Mother doesn’t understand me,’ she protests as her mother tries to communicate with her. Annoyed at being frequently compared with her sister Margot, Anne fights to overcome sibling rivalry. Her relationship with Mrs Van Daan fluctuates between friendly and antagonistic. An incessant talker, Anne is always at odds with Mr Dussel, her roommate, who longs for quiet.

Despite the endless personality clashes, magnified by the group’s claustrophobic quarters, Anne manages to adjust to her plight.

Very much aware of the outside world, Anne listens to radio reports of the war’s progress. She fears for her best friend Lies, who has been taken to a concentration camp, and for herself and her companions as the sounds of air raids and gunfire penetrate their shelter. In an effort to overcome her fears, Anne confides in her diary, which she names ‘Kitty’ and treats as a personal friend.

Anne shows strength and courage in her writing, retaining her faith in human beings: ‘In spite of everything, I still believe in the goodness of man.’

Anne’s optimism contrasts with Peter Van Daan’s initial pessimism. Rather quiet and bewildered by the sudden upheaval in his life, he spends much of the time locked in his own room. Anne gradually develops a romantic interest in Peter and convinces him not to succumb to pessimism but to hope for a better future. Limited to going from room to room, they talk, share ideas, and support each other.

Mrs Van Daan seems to be an ordinary, doting mother at the diary’s beginning, but as the situation becomes more tense she grows panicky and neurotic.

Moody and constantly complaining, she also boasts about her youth, her numerous boyfriends, and her active social life, much to the embarrassment of her son Peter. As events unfold, she begins to nag her husband and disturb the other people in hiding, fighting with Mrs Frank over trivial matters such as whose dishes to use. Mr Van Daan, on the other hand, remains reticent and tries to cover for his wife’s shortcomings. But after desperation drives him to steal potatoes from the others, the roles are reversed, and Mrs Van Daan tries to protect her husband.

Anne portrays her own family in more sympathetic terms. Her mother is a quiet woman who attempts unsuccessfully to communicate with Anne. Mrs Frank is puzzled because Anne lacks the natural affection and respect for her that Margot demonstrates. Kind and intelligent, Margot’s reserved nature and obedience contrast sharply with her sister’s rebelliousness.

Anne’s father leads the group, making the decisions, enforcing the rules, and providing encouragement.

Despite the selflessness and courage of some, such as the Dutch people who feed and shelter the Jews, an underlying theme of Anne’s account is man’s inhumanity to man. Simply because of her religious beliefs, Anne is confined and lives in constant fear of death. Eventually, she does die, along with over six million other Jews during World War II.

The theme of imprisonment is also important. Confined to a small area for more than two years, the eight people are trapped by a hateful society. They must follow specific rules so as not to be detected by the workmen in the warehouse below: during the day, they must walk in stockinged feet and cannot flush the toilet.

They can never leave the building and every unexpected phone call or suspicious noise from below causes fear and apprehension. That Anne continues to grow mentally and emotionally under these conditions suggests the ability of the human spirit to transcend physical imprisonment.

Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl is a coming-of-age story, tracing Anne’s emotional growth as she exchanges childlike behaviour and attitudes for a more adult outlook on life. A popular theme in literature, other examples of coming-of-age stories are J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Other themes include loneliness, romantic and filial love, and optimism and hope.

Anne’s words are often remarkably hopeful despite the ever-present threat of death. Perhaps the most quoted line—“I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are really good at heart”—captures the diary’s central paradox: optimism in the midst of oppression. This statement has been both lauded for its courage and critiqued as tragically naive, particularly considering Anne’s eventual death from typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in early 1945.

Symbolism abounds in the text. The Annex becomes a symbol of both imprisonment and safety. Kitty, the fictional friend to whom Anne addressed her diary entries, represents Anne’s yearning for emotional connection and an outlet for her self-expression. Kitty, though a figment of Anne’s imagination, became her most intimate confidante: “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone”.

Another recurring symbol is the moveable bookcase that conceals the Annex—a physical manifestation of the thin veil between survival and discovery, hope and despair.

Literary Technique

Anne records her personal actions and feelings in warm, simple conversational language. Her images are vivid; her writing is sincere. She addresses Kitty, the diary, as a human being as she uncovers her true self.

Anne describes the characters’ daily trials and tribulations in such detail that the reader gets to know them all intimately. These details, combined with Anne’s unaffected style, make for all the more realistic a story, and account for the diary’s universal appeal.

Anne Frank’s diary is, in a sense, an example of dramatic irony because, unlike the narrator, the reader knows how the story will end. This knowledge on the part of the reader lends a sharp poignancy to the optimism of Anne’s last entry.

Historical And Social Context

The primary social issue addressed in Anne Frank’s diary is the persecution of the Jews. Anti-Semitism can be traced back to biblical times and has taken various forms throughout modern history.

In the Middle Ages, Jews were forced to wear ‘Star of David’ badges to distinguish them from the rest of society. Designed to humiliate, the badge was referred to as the ‘Badge of Shame’. When the Nazis occupied the Netherlands, they required Jews to wear the same badge.

The Nazis also forced Jews to turn in their bicycles; they could shop only during restricted hours and could buy goods only from ‘Jewish shops’.

Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl is an invaluable source of evidence as to the impact of the Holocaust on ordinary people’s lives.

Anne shares her knowledge and feelings about the suffering the war has brought and tells of families separated and taken away in cattle trucks to a place of no escape. She realizes that the terrible conditions under which she lives in hiding are nonetheless better than those endured by Jews on the outside.

Genre-Specific Elements

Though not fiction, The Diary of a Young Girl carries literary qualities often found in well-crafted novels: tension, character development, plot arcs, and emotional catharsis. Anne’s ability to sketch the people around her with vivid honesty—sometimes harsh, sometimes tender—renders the diary a masterclass in character portrayal.

The diary’s dialogic elements, though not presented as actual conversations, are infused with emotional realism. Her observations about her family, such as “Mother and I are so different. We clash on everything,” show the raw tension and emotional complexities of familial relationships under extreme stress.

The genre of the diary allows readers intimate access to Anne’s private world—making this book ideal for readers of autobiography, Jewish literature, World War II history, and adolescent psychology. It is recommended particularly for high school and college students, educators, and anyone seeking a personal lens into Holocaust history.

Evaluation

Strengths: The Voice that Echoes Across Time

The greatest strength of The Diary of a Young Girl lies in its unmistakable authenticity. Anne Frank’s voice is at once intimate and universal. Her writing, though penned between the ages of 13 and 15, exhibits a precocious insight rarely found in adult memoirs. She muses on war, womanhood, love, and mortality with clarity and nuance. One of the most compelling passages reads: “I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death!”. This line alone crystallizes Anne’s desire to transcend her temporal confinement and reach out to posterity.

Her prose ranges from light-hearted—”Paper is more patient than people”—to philosophical reflections on identity and justice, allowing readers to witness a young girl’s transformation under siege. The diary is, in essence, both a survival narrative and a coming-of-age story—a duality that makes it unforgettable.

Weaknesses: Gaps and Editorial Silence

No honest review would be complete without acknowledging the diary’s limitations.

One notable weakness is the missing sections due to the confiscation and partial destruction of Anne’s notebooks after her arrest. There is also editorial intervention. Otto Frank admitted to omitting parts that discussed Anne’s sexuality and her critical views of her mother, citing concerns over public reception and respect for family privacy.

While understandable, these edits initially diluted some of Anne’s emotional truth. Thankfully, later unabridged versions, including the 1995 definitive edition, restored much of this content.

Impact

Emotionally, the impact of The Diary of a Young Girl is seismic. It breaks through statistics and turns six million into one face, one voice, one girl who once dreamed of being a writer. Anne’s life—and death—represents the countless untold stories lost in the Holocaust. The diary allows readers to mourn not only for what was but also for what could have been.

Intellectually, the diary serves as a primary historical document. It is cited in over 1,000 scholarly works and has appeared in school curricula in more than 60 countries. As of 2019, it had been translated into over 70 languages and sold more than 35 million copies worldwide. The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, which receives over 1.2 million visitors annually, stands as a living monument to the diary’s enduring legacy.

Comparison with Similar Works

Compared to other Holocaust memoirs such as Elie Wiesel’s Night or Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Anne’s diary is distinct in its gentleness and optimism. While Wiesel and Levi expose the horrors inside concentration camps, Anne reveals the psychological tension of life in hiding—less violent in description, yet equally haunting. Her story ends before the climax of terror, but that absence makes the tragedy even more jarring.

Reception and Criticism

While Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl is celebrated worldwide as a powerful testament to hope and resilience during the Holocaust, it has also faced criticism and bans over the years. Critics have objected to the diary’s candid discussions of Anne’s emerging sexuality and her sometimes unflattering portrayals of people around her, including her mother and others sharing the Secret Annex. These passages were initially omitted in early editions but were later restored in more complete versions.

In the 2010s, schools in Culpeper County, Virginia, and Northville, Michigan, temporarily banned the diary or shifted to using older, censored editions due to complaints about these explicit references. Some parents and educators called the passages “sexually explicit” or “pornographic” for middle-school students. A Texas teacher was fired in 2023 for assigning an illustrated adaptation of the diary, with school officials calling it “inappropriate” for middle schoolers.

Moreover, some political groups have criticized the diary for its perceived support of Jewish identity and for allegedly promoting Zionism. For instance, Hezbollah called for a ban on The Diary of a Young Girl in Lebanese schools in 2009, arguing it was biased towards Jews and Israel.

Despite these criticisms, historians and scholars have consistently defended the diary’s authenticity and educational value. Forensic studies have verified that the handwriting matches Anne’s, and experts have authenticated the materials used in the diary’s creation. The diary remains a cornerstone of Holocaust education and a moving account of a young girl’s voice amid the horrors of war.

The diary was met with critical acclaim from its inception. Jan Romein, a Dutch historian, wrote in 1946: “This apparently inconsequential diary by a child… embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence of Nuremberg put together”. Eleanor Roosevelt, who penned the introduction to the English edition, called it “one of the wisest and most moving commentaries on war and its impact on human beings.”

Yet the diary has not been without controversy. Some critics, including Holocaust scholar Dara Horn, have argued that its sanitized portrayal omits the full horror of Nazi brutality and allows readers to rest in the false comfort of Anne’s idealism. Others criticize its use in educational settings as too mild a representation of the Holocaust. Still, this criticism often underscores the very reason for its universal appeal—it introduces the unimaginable through the imaginable: the eyes of a child.

Adaptations: From Page to Stage and Screen

Anne’s story has been adapted multiple times, most notably in the Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Diary of Anne Frank (1955) and its subsequent 1959 film adaptation. These adaptations, while bringing her story to wider audiences, also faced scrutiny for downplaying Jewish identity and sanitizing uncomfortable truths. More recent productions, including the 2014 stage play Anne and Ari Folman’s 2021 animated film Where Is Anne Frank, have attempted to restore this depth, placing Anne’s legacy in the context of modern refugee crises and broader human rights issues.

Valuable Information for Readers

For readers today, The Diary of a Young Girl is more than historical testimony—it is a deeply relatable, emotionally immersive, and morally instructive work. It is a recommended read not only for history buffs or literary enthusiasts but for anyone seeking to understand human dignity under duress. Its keywords—Holocaust diary, Anne Frank, Nazi occupation, adolescent voice, and Jewish literature—are not just some terms, but vital searchlights that lead to historical truth.

Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading The Diary of a Young Girl today—decades removed from World War II, yet surrounded by new conflicts, refugee crises, and rising intolerance—feels less like revisiting the past and more like decoding the present. In Anne Frank’s world of whispers and fear, we recognize our modern anxieties: censorship, surveillance, racial hatred, and the desperate search for sanctuary.

What strikes me most is Anne’s resilience—not born of physical strength or power, but of intellect and imagination. Amid the grinding monotony of hiding, Anne writes, “I can shake off everything if I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn”. These words resonate not just as teenage musings, but as a powerful psychological strategy—writing as therapy, self-expression as rebellion. In today’s classrooms, where mental health is a rising concern, this diary is more than literature; it’s a lifeline.

In many ways, Anne Frank exemplifies the ultimate growth mindset. Her diary documents a transformation from naive girl to contemplative thinker. Early entries brim with superficial frustrations—“I can’t stand being cooped up for so long”—but by 1944, she is reflecting on gender roles, mortality, and identity: “Women should be respected as well! Generally speaking, men are held in great esteem in all parts of the world, so why shouldn’t women have their share?”. These reflections make Anne startlingly modern—relevant to both gender equality and educational discourse on critical thinking.

The educational relevance of The Diary of a Young Girl also lies in its power to foster empathy. When students read statistics like “six million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust,” many struggle to comprehend the magnitude. But when they read about a single girl sneaking a peek out a curtained window or blushing over a boy named Peter, they understand. Anne makes the abstract personal.

Moreover, her voice dismantles the common misconception that victims of history are silent. She wasn’t. She spoke in the language of letters, in ink-stained truths. And it is precisely because she wrote from inside the storm, rather than after it, that her words ring with such poignant urgency. As Holocaust education faces new challenges—denial, distortion, and diminishing first-person testimony—books like The Diary of a Young Girl become invaluable pedagogical tools.

In the digital age, where misinformation spreads like wildfire, educators must teach critical reading and ethical reasoning. Anne’s diary, filled with both factual recounting and emotional introspection, provides the perfect balance for such instruction. It asks students not just to memorize dates but to ask questions: What would I have done? Could I stay silent? What does freedom mean?

And perhaps most urgently, Anne’s diary teaches the cost of indifference. As Elie Wiesel famously warned, “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.” Anne sensed this too, writing: “What is done cannot be undone, but one can prevent it happening again.” Her diary is not only a memoir of survival—it is a call to conscience.

In that sense, assigning The Diary of a Young Girl isn’t simply a curricular decision—it’s a moral one. It introduces students to not only the horrors of genocide, but the miracle of hope. It confronts the darkest recesses of human history while illuminating the irrepressible light of a 15-year-old girl who refused to be silenced.

The Diary of Anne Frank Quotes

- “Paper has more patience than people.” — Anne’s realization that writing offers her more solace than human interaction .

- “I can shake off everything as I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn.” — Anne on the power of writing to heal and renew.

- “I don’t think of all the misery, but of the beauty that still remains.” — A famous line reflecting her resilience.

- “Despite everything, I believe that people are really good at heart.” — Anne’s optimism about humanity.

- “Think of all the beauty still left around you and be happy.” — Another reminder of her hopeful outlook.

- “No one has ever become poor by giving.” — Anne’s reflection on generosity.

- “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” — Her call to action.

- “I don’t want to have lived in vain like most people. I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met.” — Her sense of purpose.

- “I must uphold my ideals, for perhaps the time will come when I shall be able to carry them out.” — Her determination.

- “People can tell you to keep your mouth shut, but that doesn’t stop you from having your own opinion.” — Anne’s assertion of individuality.

- “As long as this exists, this sunshine and this cloudless sky, and as long as I can enjoy it, how can I be sad?” — Her appreciation of small joys.

- “Who would ever think that so much went on in the soul of a young girl?” — Her acknowledgment of her depth.

- “I know what I want, I have a goal, an opinion, I have a religion and love.” — Her self-awareness and conviction.

- “I’ve found that there is always some beauty left—in nature, sunshine, freedom, in yourself; these can all help you.” — Anne’s way of finding hope.

- “Where there’s hope, there’s life. It fills us with fresh courage and makes us strong again.” — Her belief in hope.

- “The weak fall, but the strong will remain and never go under!” — Her sense of resilience.

- “A person who has courage and faith will never die in misery!” — Anne’s belief in strength through adversity.

- “I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness, I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too.” — A darker reflection on the world’s condition.

- “I long to ride a bike, dance, whistle, look at the world, feel young and know that I’m free.” — Anne’s longing for normalcy.

- “Our lives are fashioned by our choices. First we make our choices. Then our choices make us.” — Her insight into personal responsibility.

Conclusion

As we close the pages of The Diary of a Young Girl, we are not left with closure, but with a haunting echo. Anne Frank’s voice—so full of promise, curiosity, and introspection—does not reach a natural ending. It halts. Abruptly. Tragically. Her final entry, dated August 1, 1944, reads simply, “I keep trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be… if only there were no other people in the world”. Three days later, the Gestapo arrived. And yet, in every word she left behind, Anne remains vibrantly alive.

Summary and Overall Impression

The Diary of a Young Girl is more than a historical document or a teenager’s journal—it is a rare artifact of lived experience that continues to educate, inspire, and challenge readers across generations. Its key themes—fear and hope, confinement and freedom, identity and self-expression—are not bound by time or geography. It is no exaggeration to call this work a cornerstone of 20th-century literature, a universal mirror reflecting both the cruelty and courage within us all.

Audience Recommendation

This diary is indispensable for students of history, literature, psychology, and human rights. It is ideal for young adults beginning to grapple with moral complexity, yet profound enough to challenge scholars and educators. It is essential reading during Holocaust Remembrance Day, in high school literature courses, and in any curriculum aiming to teach empathy, resilience, and the ethics of memory.

Final Reflections: Why This Book Still Matters

In an era where algorithmic noise often drowns out authentic voices, Anne Frank’s diary persists because it is irrefutably human. It was not written to be read by millions; it was written because a 13-year-old girl needed someone to talk to. That makes it one of the most honest books ever written. And perhaps that’s why, despite wars, denials, and digital distractions, it continues to speak to us.

To read Anne Frank is not to pity her—it is to witness her. To honor her legacy is not merely to remember her death, but to amplify her life. And to teach her diary is not to freeze history in amber—it is to kindle the conscience of future generations.

“How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” — Anne Frank

Let us take her at her word.