Last updated on May 14th, 2025 at 09:33 pm

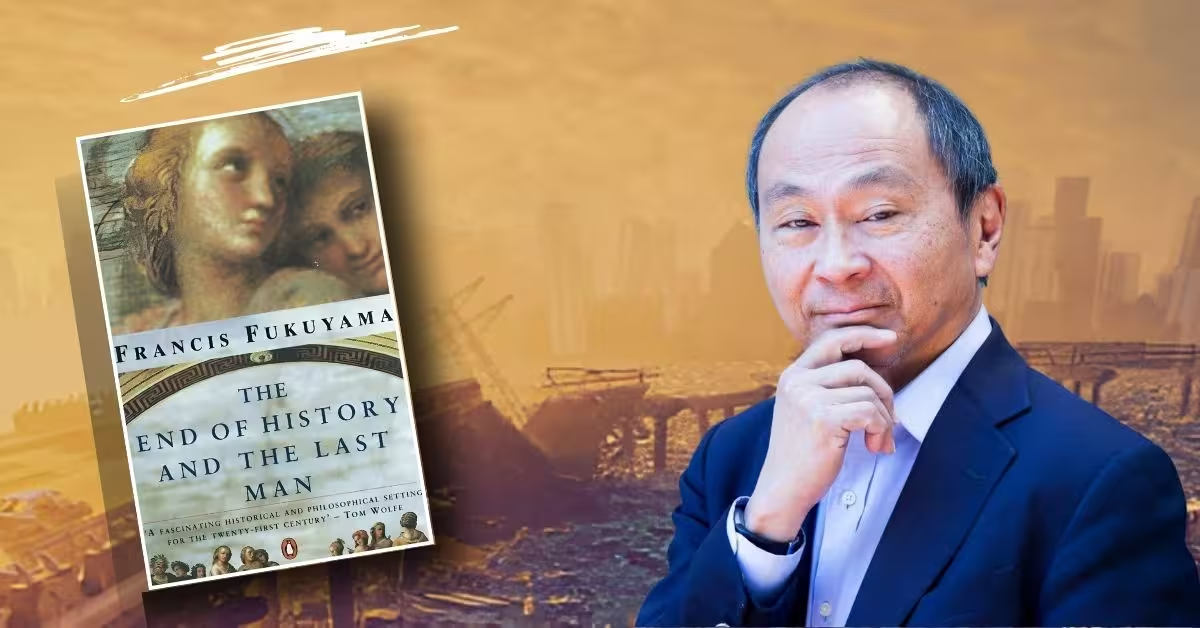

The End of History and the Last Man by Francis Fukuyama, first published in 1992 by Penguin Books, is a philosophical-political work that continues to ignite debate decades after its release. Emerging from the ashes of Cold War ideological combat, this book is a bold, intricate thesis on the trajectory of political evolution, predicting the potential culmination of humanity’s ideological journey in liberal democracy.

Fukuyama, a political scientist with a Ph.D. from Harvard and a former policy analyst at the U.S. State Department, brought both theoretical insight and policy experience to his work.

By 1992, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Soviet Union had dissolved, and the world was reeling with optimism, confusion, and a desperate search for meaning. Amidst this, Fukuyama extended the ideas of Hegel and Kojève to argue that we may be witnessing not the end of events—but the end of History (capital ‘H’): the ideological evolution of humanity had reached its apex.

As he writes in the introduction:

“Liberal democracy may constitute the ‘end point of mankind’s ideological evolution’ and the ‘final form of human government,’ and as such constituted the ‘end of history’”.

At its core, The End of History and the Last Man proposes that liberal democracy, supported by free-market capitalism and informed by universal principles of individual dignity and recognition, represents the final form of governance. It may not be perfect, but it is the most ideologically complete. Fukuyama contends:

“The ideal of liberal democracy could not be improved on”.

He does not mean history in the journalistic sense of events unfolding daily, but rather in the Hegelian-Marxist sense—a teleological progression toward an ideal society.

In the sections that follow, we’ll walk through a comprehensive, human-centered, and critically engaged reading of this text—unpacking not only its philosophical depths but its implications for today’s fractured, post-truth political landscape.

Table of Contents

1. Background: Fukuyama’s Bold Thesis in a Post-Cold War World

Published in 1992, The End of History and the Last Man was Francis Fukuyama’s attempt to make sense of a rapidly transforming world order after the Cold War. The Berlin Wall had fallen. The Soviet Union had dissolved. Authoritarian regimes were collapsing like dominos. Amid this geopolitical earthquake, Fukuyama argued that what we were witnessing was not just another shift in international power—but a full stop in the evolutionary trajectory of political ideologies.

Drawing from the philosophical lineage of G.W.F. Hegel, who saw history as a dialectical progression of ideas, and Alexandre Kojève, who interpreted Hegel to mean that history culminates in a rational state, Fukuyama’s claim was bold: liberal democracy is the final form of human government. History—understood as an ideological struggle between competing visions of governance—had essentially ended.

Fukuyama didn’t argue that events would cease to occur or that conflict would vanish, but that the ideological debate about how human societies should be structured was largely over. He built on his 1989 essay, The End of History?, published in The National Interest, which laid the intellectual groundwork for the book.

While the idea resonated with the optimism of the early 1990s—when the world seemed to be heading toward open markets, multiparty elections, and individual rights—it was never a declaration of utopia. Instead, it was a philosophical assertion about the direction of political evolution.

2. Summary

Francis Fukuyama organizes The End of History and the Last Man into five thematic parts that together make a comprehensive case for liberal democracy as the ideological terminus of human evolution.

It is a grand narrative blending philosophy, political science, history, and psychology. The structure is both argumentative and developmental—each part builds on the last, moving from the historical crisis of belief, to a defense of rational historical progression, and finally, to a psychological and philosophical examination of the human condition in the liberal age.

Part I: An Old Question Asked Anew

Pivotal Argument: The Legitimacy of a Universal History Must Be Reconsidered in the Wake of Liberalism’s Global Success

In the first part of The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama returns to a profound and largely abandoned philosophical question: Can there be a coherent, directional history of mankind?

After the devastation of two world wars, the atrocities of fascism and communism, and the nuclear anxiety of the Cold War, most intellectuals had grown skeptical of any notion of progress. To suggest that history might have a telos—an endpoint—seemed not only naïve but dangerously arrogant. And yet, Fukuyama argues, something unprecedented had occurred by the late 20th century: the ideological consensus around liberal democracy.

The term “history” here is not to be confused with the simple unfolding of events. Fukuyama distinguishes between “history” as journalism and “History” (capital H) as the philosophical evolution of human political and social systems. Drawing on Hegel, he writes:

“And yet what I suggested had come to an end was not the occurrence of events, even large and grave events, but History: that is, history understood as a single, coherent, evolutionary process, when taking into account the experience of all peoples in all times. This understanding of History was most closely associated with the great German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel.”

Historical Pessimism vs. Liberal Triumph

Fukuyama opens with a diagnosis of 20th-century pessimism. Following the horrors of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, intellectuals like Emile Fackenheim and H.A.L. Fisher argued that historical progress had been irrevocably shattered. How could one believe in providence, improvement, or moral advancement after the Holocaust? This pessimism became so culturally dominant that even the ideological superiority of communism seemed more plausible than the dream of a peaceful liberal order.

Yet Fukuyama juxtaposes this with the collapse of authoritarian regimes, from Franco’s Spain to the Eastern Bloc. By the 1990s, liberal democracy wasn’t just dominant in the West—it was expanding globally.

He observes:

“Authoritarian dictatorships… have been collapsing. And while they have not given way in all cases to stable liberal democracies, liberal democracy remains the only coherent political aspiration that spans different regions and cultures around the globe”.

Thus, Fukuyama sees in this global shift not merely coincidence or contingency, but something teleological—suggesting direction, movement toward a final form.

Rehabilitation of “History” as a Philosophical Narrative

The most radical move in Part I is Fukuyama’s revival of Hegelian dialectics in an age when postmodernism and realpolitik had dismissed all such grand narratives. Hegel believed that history unfolded as a rational process—the unfolding of freedom through successive forms of recognition. Marx adapted this idea toward communism, imagining a classless utopia at the end of labor’s exploitation.

Fukuyama, however, parts with Marx and returns to Hegel via Alexandre Kojève, a Russian-French philosopher who claimed that Napoleon’s defeat of Prussian monarchy at Jena in 1806 signified the end of History—not in the sense of stopping time, but in the resolution of humanity’s ideological striving. Kojève believed that liberal democracy, particularly in its French Revolutionary form, satisfied mankind’s deep yearning for equality and dignity.

Fukuyama agrees—with caution. He does not say that we are in utopia but that we have reached the highest known ideological resolution to the human political condition. He admits that problems remain—inequality, social alienation, cultural decline—but they are not philosophical flaws in liberal democracy. Rather, they are implementation gaps or the result of material circumstance.

“These problems were ones of incomplete implementation… rather than of flaws in the principles themselves”, Fukuyama writes.

The Dual Mechanisms Driving History

Fukuyama lays the groundwork for the two pillars he will expand in later parts:

- Modern natural science (the technological-economic engine)

- The struggle for recognition (thymos, the psychological-moral engine)

He suggests that it is no longer tenable to claim history is directionless. Technological and military superiority have incentivized states to modernize. Economically, free-market capitalism has lifted billions. Politically, democracy has expanded its borders.

But more subtly—and perhaps more importantly—humans are increasingly seeking to be recognized as free and equal. The material engine alone cannot explain liberal democracy. There must be a moral-emotional mechanism, and that is where thymos comes in.

The Crisis of Legitimacy in Strong States

One of the most illuminating arguments in this section is Fukuyama’s reinterpretation of why authoritarian regimes collapse. Not simply because of economic failure or rebellion, but because of a crisis of legitimacy among the elite.

“A lack of legitimacy among the population as a whole does not spell a crisis… unless it begins to infect the elites… particularly those that hold the monopoly of coercive power”.

This analysis presciently explains the suddenness with which the Soviet bloc unraveled. Communist regimes did not fall because they were defeated militarily or economically (many were still viable), but because even their own elites stopped believing in their ideological legitimacy. The internal coherence of the system dissolved.

This pivot from brute force to belief as the root of regime stability is a powerful conceptual shift. It implies that liberal democracy’s dominance isn’t just material—it’s ideational. People not only want it—they believe in it.

Tension Between Realism and Idealism

Interestingly, Fukuyama positions his theory against realism in international relations. Where Kissinger and other realists believed the Cold War would persist indefinitely because human nature was static and power-hungry, Fukuyama argues the opposite: that the moral imagination of human beings evolves, and that the yearning for recognition is slowly converging toward liberal democratic forms.

He directly critiques realists like Huntington and Kirkpatrick, who believed authoritarianism was natural to some regions. Fukuyama instead sees a slow, global convergence—driven by economic modernization, but fulfilled by political and moral institutions.

Conclusion of Part I: Why We Must Revisit the Question of History

Part I ends with an invitation—not a conclusion. Fukuyama does not demand that the reader accept that history is over. Instead, he invites a renewed philosophical inquiry:

“While drawing on the ideas of philosophers like Kant and Hegel… I hope that the arguments presented here will stand on their own”.

This humility is one of the book’s subtle strengths. Fukuyama isn’t declaring victory, he is proposing a framework—one in which liberal democracy is not just dominant but ultimately justified by both rational and moral standards.

Part I, then, is the opening salvo in a larger debate. It raises the stakes. If Fukuyama is right, then all of today’s challenges—tribalism, inequality, nationalism, algorithmic echo chambers—are not signs that liberalism has failed. Rather, they are crises of liberalism’s soul—growing pains of a still-emerging global consciousness centered on freedom and recognition.

Part II: The Old Age of Mankind

Pivotal Argument: Modern Natural Science Drives Historical Progress—But Only Halfway to Liberal Democracy

In Part II of The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama attempts his first major demonstration of why history—understood as a philosophical, directional movement—can be said to have reached a culmination point. He does this by identifying modern natural science as a historical mechanism: a universal force that propels all societies toward certain structural similarities. While this economic and technological modernization explains much of human convergence, Fukuyama admits that it alone cannot deliver political liberty. The yearning for liberal democracy, he argues, must come from something deeper.

1. Modern Science as the Engine of Uniformity

Fukuyama begins Part II with a remarkable claim: modern natural science has become the most powerful homogenizing force in history. It demands from societies certain adaptations—technological, economic, institutional—that ultimately narrow the paths of political development.

He writes:

“Technology confers decisive military advantages… [and] makes possible the limitless accumulation of wealth… [which] guarantees an increasing homogenization of all human societies, regardless of their historical origins or cultural inheritances”.

In this formulation, modern science is not neutral. It carries within it a logic: efficiency, rationalization, centralization, and innovation. Any society that hopes to defend itself or prosper economically must modernize—or perish. The laws of physics and the structure of technology are universal; therefore, societies must bend to them or fall behind.

This leads to several observable convergences across disparate societies:

- The centralization of the state

- The urbanization of populations

- The standardization of education

- The functionalization of roles (tribe → bureaucrat, elder → civil servant)

- The rise of the consumer economy

Thus, whether in Taiwan or Turkey, Chile or China, the basic shape of society under the pressures of modernization starts to look similar.

2. The Economic Interpretation of History—And Its Limits

In drawing out this logic, Fukuyama is engaging with the Marxist tradition, particularly the materialist view that economic structure determines social and political outcomes. However, while Marx saw capitalism as a transitional phase toward socialism, Fukuyama argues the opposite: capitalism, driven by modern science, is not a stepping stone to socialism, but the destination.

This is a powerful reversal. He states:

“Unlike its Marxist variant… [this interpretation] leads to capitalism rather than socialism as its final result”.

The logic of science leads to capitalism because only capitalism effectively mobilizes innovation, investment, and individual initiative on a global scale. Planned economies can simulate industrialization up to a point (as in Stalin’s Russia or Mao’s China), but they stall when confronted with the information demands of post-industrial complexity.

However, Fukuyama is not content with this economic interpretation. He sees a major flaw: while modernization may make societies look alike, it does not necessarily make them free. He writes:

“There is no economically necessary reason why advanced industrialization should produce political liberty”.

In fact, he points out, there are many historical cases where economic modernization coexists with political authoritarianism:

- Meiji Japan: rapid industrial growth under a centralized imperial rule

- Bismarckian Germany: modern military and welfare systems without democracy

- Modern Singapore and China: high-tech economies with limited civil liberties

So while modern natural science may be sufficient for capitalist economic development, it is insufficient to explain the universal appeal of liberal democracy.

This is where Fukuyama’s conceptual architecture begins to take shape. Science and capitalism explain why modern societies converge materially—but not why they converge politically.

3. Capitalism: Engine or Illusion?

Fukuyama walks a tightrope here. He is not a cheerleader for capitalism in the neoliberal sense. Rather, he sees capitalism as a kind of historical inevitability, forced upon societies by the logic of science and competition.

But this comes with a major cost. If modernization happens regardless of democracy, then liberty is not guaranteed. Technocrats may rule effectively. Authoritarian systems may outperform democracies in certain metrics. The market does not inherently produce freedom; it produces efficiency.

This insight foreshadows Fukuyama’s later concern with the “last man”—the person who has everything except purpose. It also anticipates modern concerns about algorithmic capitalism, surveillance economies, and illiberal technocracies.

In many ways, this section of the book has aged brilliantly. It explains how regimes like China can thrive economically while repressing political freedoms. It also explains the convergence of consumerist aesthetics between authoritarian and democratic states.

Modernity, it turns out, is not just democratic—it is also deeply ambivalent.

4. The Uniformity of Needs and the Erosion of Tradition

Another powerful insight in Part II is Fukuyama’s description of how modernization erodes traditional sources of authority.

He writes:

“They must unify nationally on the basis of a centralized state… replace traditional forms of social organization like tribe, sect, and family with economically rational ones”.

This shift leads to a uniform set of challenges and desires: education, jobs, mobility, security, healthcare. As these needs become universalized, so do expectations. This, in turn, puts pressure on governments—regardless of ideology—to respond with systems that recognize individual dignity.

The irony here is that liberal institutions, which arise to safeguard individual autonomy, may emerge not from ideology, but from functionality. As populations become literate, connected, and upwardly mobile, they demand more responsive governance—not simply more goods.

But Fukuyama reminds us: the mere existence of economic wants doesn’t create liberalism. For that, we need thymos—a longing not just for things, but for moral recognition.

Thus, we arrive at the limits of Part II’s framework. Modern natural science brings about material convergence—but it cannot account for the political soul of liberal democracy.

“Man is not simply an economic animal… economic interpretations of history are incomplete and unsatisfying”.

This final sentence is a turning point. It sets the stage for Part III, where Fukuyama introduces the struggle for recognition as the missing piece.

5. Liberal Democracy as the Moral Superstructure

Although Part II is framed as an economic and technological argument, its underlying purpose is to clear space for the moral-political question: Why democracy? If material incentives alone cannot explain it, then we must look elsewhere.

And so, Part II ends with a crucial insight:

“Desire and reason are together sufficient to explain the process of industrialization… but they cannot explain the striving for liberal democracy”.

Thus, Fukuyama gestures toward the need for a non-materialist theory of history—one rooted in thymos, dignity, and recognition.

In other words, if Part II describes how societies modernize, Part III will describe why humans seek freedom.

Conclusion of Part II: Half the Story, and No Further

Part II of The End of History and the Last Man is not a complete argument—it is half the scaffolding. Fukuyama brilliantly articulates how the logic of science and technology shapes the modern world. He shows that history is not random; it bends toward complexity, information, and economic rationalization.

But he also shows that this logic does not bend toward justice on its own. Nor does it deliver freedom. In fact, it can thrive in regimes that suppress the very spirit of democracy.

To explain why people choose democracy—to understand the soul of liberty—we must go beyond modern science. That journey begins in Part III: The Struggle for Recognition.

Part III: The Struggle for Recognition

Pivotal Argument: The Desire for Recognition—Not Just Reason or Appetite—Is the True Driver of History

In Part III of The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama steps away from the material explanations of history and enters the domain of the soul. Here, he proposes that neither economic necessity nor scientific rationality can explain why human beings fight for liberty. Instead, he introduces a neglected but vital force in political theory: thymos, the part of the human psyche that craves recognition, dignity, and honor.

This move is not just philosophical—it is profoundly political. In our current age of identity politics, cultural conflict, and ideological polarization, Fukuyama’s revival of thymos feels not only prescient but prophetic. If Parts I and II showed us how we got here, Part III shows us why we keep fighting, even when all material needs are met.

1. What Is Thymos? And Why Did We Forget It?

Drawing on Plato’s Republic, Fukuyama distinguishes the human soul into three parts:

- Desire (epithumia) – for material goods, comfort, pleasure.

- Reason (logistikon) – for order, knowledge, survival.

- Thymos (thymoeides) – the spirited part that seeks recognition of one’s worth.

While modern political theory, particularly Hobbesian and utilitarian models, focus almost entirely on the first two—desire and reason—Fukuyama insists that the third, thymos, is what propels revolutions, resistance, and democracy.

“Man differs fundamentally from the animals… because he wants to be recognized as a human being, that is, as a being with a certain worth or dignity”.

This desire for recognition, or megalothymia (the desire to be seen as superior), has driven the greatest political transformations in history—from the Peloponnesian War to the American civil rights movement.

Fukuyama laments that the Western liberal tradition—by reducing politics to a contract between selfish individuals—has neglected the spiritual dimension of human motivation.

2. Master and Slave: The Dialectic of Recognition

Fukuyama’s most important intellectual debt in this section is to Hegel, specifically his famous master–slave dialectic. In this dynamic, two self-conscious beings confront one another and each demands recognition of their superiority. A struggle ensues. The one who fears death submits—becoming the slave—while the other, willing to risk his life, becomes the master.

But the twist is devastating: the master receives no meaningful recognition because it comes from someone he does not respect (a slave). The slave, meanwhile, becomes self-aware through labor, gaining inner freedom and consciousness.

Fukuyama explains:

“The slave must work, and in working transforms not only the world but his own inner nature”.

This struggle, repeated across generations and societies, propels humanity toward increasingly complex forms of mutual recognition—culminating, potentially, in liberal democracy, where each person is recognized equally as an autonomous, dignified being.

3. Isothymia and Megalothymia: Equality vs. Superiority

Fukuyama introduces two critical terms to deepen the analysis:

- Isothymia: the desire to be recognized as equal to others.

- Megalothymia: the desire to be recognized as superior to others.

Liberal democracy appeals to isothymia. It guarantees equal rights, legal protection, and civil dignity to all. It tells each citizen: you matter just as much as anyone else.

But human beings are not satisfied with equality alone. Many still crave greatness, distinction, victory. This megalothymia drives individuals to seek unequal recognition—which liberal democracies are structurally designed to resist.

“Democracy satisfies the isothymotic part of the soul… but cannot satisfy the megalothymotic part”.

This is where the paradox emerges. Liberal democracy is stable because it pacifies the population through equality—but it is always at risk from those who find such peace intolerable. The great man, the tyrant, the revolutionary, or the fanatic may arise when megalothymia is unfulfilled.

In this sense, democracy must constantly manage the tension between equality and excellence, between the masses and the exceptional individual.

4. Historical Struggles and the Demand for Dignity

Fukuyama gives a sweeping reinterpretation of major political events—from the French Revolution to the Cold War—as expressions of thymotic conflict. The struggle for universal suffrage, civil rights, and decolonization were not merely materialist revolts—they were demands to be recognized as full human beings.

“What is common to all of these movements… is a desire for the recognition of dignity, of status, of identity”.

What the slaves of history have always wanted was not just bread, but honor. This, he argues, is what makes the liberal democratic promise so powerful: it not only feeds people but affirms them.

Importantly, this understanding reorients how we view modern political movements. Even terrorism, nationalism, and ideological extremism—however deplorable—are often thymotic expressions. They emerge from communities or individuals who feel disrespected, humiliated, or ignored by the dominant global order.

5. Liberal Democracy: The Institutionalization of Mutual Recognition

So what does liberal democracy do that other systems cannot?

- It creates legal equality, allowing isothymia to flourish.

- It provides meritocratic avenues for distinction, channeling megalothymia into safe outlets (politics, entrepreneurship, academia).

- It institutionalizes recognition through rights, rather than force.

In theory, this satisfies both types of thymos. But the system is fragile. When megalothymia is thwarted—when people feel unseen or oppressed—they may reject democratic norms.

This is why, Fukuyama argues, liberal democracies must cultivate civic virtue, patriotism, and shared meaning. Otherwise, the very success of the system—its peace, its sameness—can become its undoing.

“Liberalism’s weakness is that it recognizes men only as equal… not in their desire to be better”.

6. From Identity to Ideology: The Rise of Recognition Politics

Though writing in 1992, Fukuyama anticipated what we now call identity politics. From ethnic nationalism to LGBTQ+ rights to resurgent religious fundamentalism, our era is defined not by class struggle but by recognition struggles.

These movements are not just asking for resources—they are asking for validation, respect, and public acknowledgment of their dignity.

And, as Fukuyama warns, this can turn dangerous. When recognition is denied, rage ensues. But when recognition is offered too freely, without standards, it may dilute meaning—leading to status inflation and resentment.

He thus lays the foundation for what would become his later thesis in Identity (2018), where he argues that the key political question of our age is no longer who gets what, but who gets seen.

Conclusion of Part III: Recognition as the Soul of Politics

In many ways, Part III is the true fulcrum of the book. It redefines political struggle not as a clash over material scarcity, but as a spiritual contest over dignity. By returning to thymos, Fukuyama restores the soul to political theory.

This is the missing piece. Modern natural science can bring us wealth and weapons. Economic rationality can organize production. But only recognition can give us meaning. Only thymos explains why revolutions happen, why freedom matters, and why we’re never satisfied—even in the most comfortable society.

In this light, liberal democracy is not just a system of government. It is a moral achievement, a structure that acknowledges the dignity of all without collapsing into tyranny. But it is also precarious. Because the soul, unlike the stomach, is never fully satisfied.

Part IV: Leaping Over Rhodes

Pivotal Argument: Liberal Democracy Must Contend with Irrational Forms of Thymos—Including Nationalism, Religion, and the Human Need for Community and Meaning

The title “Leaping Over Rhodes” alludes to the ancient tale in which a boastful athlete claims he once performed a great jump in Rhodes, and is challenged to “leap here,” on the spot. The point, as Fukuyama adapts it, is philosophical: can liberal democracy “leap here” in the real world, not just in theory? Can it prove itself sufficient to satisfy the irrational, symbolic, emotional, and often dangerous demands of thymos?

The theme of this section is not about constructing liberalism—but about whether liberalism can withstand the continuing weight of irrational human desires.

“The institutions of liberal democracy… rest on liberal principles, but frequently depend on irrational forms of thymos as well”.

1. The Inadequacy of Rationalism Alone

Fukuyama begins by acknowledging a serious flaw in liberal theory: it assumes that human beings are primarily rational creatures motivated by self-interest. This echoes Hobbes, Locke, and utilitarian traditions, where individuals form governments to protect life, liberty, and property.

However, this rational model underestimates the irrational energies that define much of human behavior.

People risk their lives not just for survival or rights, but for:

- Honor

- Belonging

- Transcendence

- Meaning

Fukuyama points to nationalism, religious devotion, and military glory as manifestations of megalothymia—the desire to be recognized as better, distinct, or sacred. These are not modern anomalies but ancient constants.

“People are not simply economic animals… They have a sense of dignity and self-worth that demands recognition”.

This insight is critical. Rational governance may build roads and protect rights, but only identity-based narratives build nations.

2. Nationalism: The Irrational Cement of Community

One of Fukuyama’s most striking claims is that liberal democracies often owe their survival to nationalist or irrational cultural forces, not just rational design.

He examines the American and French revolutions, and even the German unification, as cases where irrational collective identity, pride, and myth-making played essential roles.

“Modern liberal democracies… depend on premodern traditions and irrational national sentiments to provide cohesion”.

Nationalism, then, becomes a double-edged sword:

- It provides solidarity, sacrifice, and stability—essential for a democracy to function.

- But it also excludes, oppresses, and intensifies violence when it morphs into ethnonationalism or chauvinism.

Fukuyama does not dismiss nationalism, but he sees it as necessary but dangerous. Liberal democracies need a shared story—but that story must be crafted carefully, to include the marginalized without sacrificing unity.

His analysis was prophetic. In our time, the resurgence of identity-based populism, far-right nationalism, and authoritarian nostalgia reflects the enduring power of irrational recognition—even in rational, rights-based systems.

3. Religion: Moral Foundation or Obstacle?

Fukuyama also tackles religion—a force often viewed as antithetical to liberal reason. Yet he asserts that religion is indispensable to the moral order of democratic societies.

“Religions are important not because their specific doctrines are true… but because they provide a grounding for the idea of human dignity”.

This is a critical argument. While secular liberalism claims to be value-neutral, Fukuyama argues that it borrows its moral architecture—human dignity, equality, the inviolability of the person—from Judeo-Christian traditions.

Stripped of these foundations, liberalism may struggle to justify itself.

Nietzsche foresaw this in his proclamation of the “death of God.” Without religious foundations, liberalism would eventually collapse into relativism, nihilism, and moral confusion.

Fukuyama doesn’t go that far, but he shares the concern: if liberalism offers only freedom from, and not a purpose for, it risks being culturally hollow.

Yet religion is also dangerous. When fused with politics, it can justify repression, theocracy, and holy war. Therefore, Fukuyama calls for a balance: secular institutions undergirded by a residual religious morality that fosters dignity, empathy, and restraint.

4. Labor and Work: Recognition in the Economic Realm

One of the more novel contributions in Part IV is Fukuyama’s discussion of work as a site of thymotic recognition.

He draws heavily on Hegel’s insight that slaves, through labor, transform both the world and themselves. In modern capitalism, work has become more than a way to survive—it’s a means of recognition.

“People work not only for money, but for the sense of self-worth that comes from being useful and recognized by others”.

This is especially relevant today. In an age of automation, digitalization, and gig economies, millions feel displaced, invisible, and disrespected—not because they are poor, but because they are deprived of meaningful roles.

Fukuyama implicitly warns that liberal societies must dignify labor, not just pay for it. Recognition, not remuneration, may be the more fundamental political demand.

This insight anticipated today’s debates about universal basic income, the dignity of work, and the rise of “bullshit jobs.”

5. Can Liberal Democracies “Leap Over Rhodes”?

The question that frames this section is whether liberal democracies can sustain themselves without the irrational sources of thymotic energy that traditional societies relied upon.

Fukuyama is ambivalent.

On one hand, he admits:

“Liberal democracy… depends on forms of recognition that are not entirely rational”.

But on the other hand, he suggests that liberal societies must find ways to channel megalothymia safely, lest it return through violence, authoritarianism, or fanaticism.

This is the central challenge of modern democracy:

- How do we cultivate patriotism without jingoism?

- How do we honor cultural traditions without exclusion?

- How do we respect religion without theocracy?

- How do we dignify excellence without undermining equality?

Fukuyama offers no easy answers—but his recognition of the problem is profound. Liberal democracy, to survive, must not just manage rights and markets—it must nourish the human spirit.

Conclusion of Part IV: Democracy’s Deepest Struggle is Spiritual, Not Structural

Part IV of The End of History and the Last Man is where Fukuyama stops theorizing and begins wrestling with liberal democracy’s soul. He understands that the greatest threat to democracy may not be authoritarianism or poverty, but meaninglessness.

Rights without ritual, freedom without identity, equality without excellence—these may leave people safe, but unsatisfied.

“The last man had no desire to be recognized as greater than others… without such desire, no excellence or achievement was possible”.

The liberal order, if it is to endure, must become more than a marketplace of interests. It must become a moral and symbolic home, capable of satisfying not just reason and desire, but the yearning for recognition.

Fukuyama’s warning is clear: if democracies fail to honor thymos—if they cannot “leap over Rhodes”—they may not collapse from invasion or revolution, but from within, through spiritual erosion.

Part V: The Last Man

Pivotal Argument: Liberal Democracy May Triumph Politically, But Spiritually It Risks Producing a “Last Man”—A Spiritually Empty, Complacent Citizen Without Aspiration or Greatness

In the final part of The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama delivers both his most triumphant and his most cautionary message. The triumph lies in the claim that liberal democracy has, for now, defeated its ideological rivals. The caution—arguably the most memorable aspect of the book—lies in the haunting specter of “the Last Man.” Drawing from Friedrich Nietzsche, Fukuyama imagines the kind of person who emerges in a world where all major battles are over, where dignity is legally guaranteed, and where struggle has vanished from political life.

This section is not about history in the traditional sense—but about human potential, meaning, and what happens after ideological victory. It brings the book full circle: if liberal democracy is the end of history, what kind of human being is left in its wake?

1. The Triumph of Isothymia

Fukuyama begins by affirming his core thesis: liberal democracy is the political system that best satisfies the universal human desire for recognition—particularly isothymia, the desire to be seen as equal to others.

He revisits Hegel’s idea that all of history is driven by the struggle for recognition. And with democracy, he argues, this struggle has—at least theoretically—found closure. The slave has become the citizen. The serf now votes. Women, minorities, and oppressed groups are increasingly seen, heard, and honored.

“The liberal democratic state values the individual as an individual and not as a member of a class, religion, or nationality”.

This achievement is not trivial. It marks the culmination of thousands of years of inequality, violence, and hierarchy. In Fukuyama’s terms, it means History has ended—not in the sense that events no longer happen, but that no better system of recognition has yet been found.

But herein lies the problem: what happens to the human soul when the struggle ends?

2. Enter the “Last Man”

Nietzsche’s Last Man—a concept Fukuyama borrows and develops—is not a villain, but something worse: a hollow victor. He is the product of a society that has removed the need for suffering, ambition, and sacrifice.

“The last man has no desire to be recognized as greater than others… He is content with the creature comforts of modern life”.

This figure is:

- Comfortable but uninspired

- Safe but mediocre

- Free but apathetic

- Equal but unfulfilled

Fukuyama uses this archetype to critique the cultural and spiritual effects of liberalism’s success. The Last Man is what happens when material needs are met, war is unnecessary, and identity has been granted—not earned.

This isn’t mere elitism. Fukuyama fears that the very virtues that make liberal democracy stable—tolerance, pacification, equality—may also extinguish greatness.

“The struggle for recognition was the motor of history… but now that it has been satisfied, that motor may no longer be running”.

It’s a bold, chilling image: a civilization that won the game, only to forget why it played.

3. The Death of Heroism and the Threat of Nihilism

Fukuyama now draws more deeply from Nietzsche. Without struggle or hierarchy, the Last Man loses contact with the heroic values that once gave life grandeur—courage, sacrifice, artistic sublimity, spiritual passion.

Without anything to risk, life becomes risk-averse. Without hardship, we forget how to endure. Without meaning, pleasure becomes the substitute.

This creates a vacuum—a kind of soft nihilism, where people are not angry or rebellious, but numb, bored, indifferent.

“The liberal democratic citizen is not so much immoral as amoral… He does not believe in anything strongly enough to risk his life for it”.

Fukuyama fears that this spiritual flattening can provoke dangerous backlashes. People, desperate for struggle or meaning, may turn to destructive megalothymia—fascism, terrorism, religious extremism—not for gain, but for the feeling of significance.

This dynamic helps explain the 21st-century rise of ideological radicalism, identity extremism, and even political nihilism. It’s not about economics. It’s about dignity, recognition, and meaningful suffering.

4. Liberalism’s Contradiction: Peace Without Purpose

Fukuyama doesn’t abandon his belief in liberal democracy. But he ends with an honest appraisal of its contradictions. It gives us peace—but maybe too much of it. It protects our rights—but flattens our sense of identity. It promotes equality—but often at the cost of striving for greatness.

This is the fundamental paradox:

“A world state… might satisfy all of the needs of desire and reason. But it might be a very boring place”.

In such a world, the risk is not revolution—but stagnation, a kind of evolutionary pause where the human spirit remains unchallenged and unexercised.

To prevent this, liberal societies must cultivate sources of meaning:

- Civic virtue: Participation in the public good

- Cultural excellence: Art, science, intellectual life

- Moral struggle: Pursuing justice, not just comfort

- Spiritual life: Whether religious or philosophical

Fukuyama implies that liberalism must build a culture—not just a structure. It must remind citizens that they are free to become excellent, not merely free to consume.

5. What Comes After the End of History?

Fukuyama ends on a note of uncertainty, even ambiguity. He doesn’t claim utopia is guaranteed. He suggests that liberal democracy is the best system so far—but whether it can keep the human spirit alive is still an open question.

“Perhaps this very prospect of centuries of boredom… will serve to get history started once again”.

That sentence captures the final irony. History may end not in triumph, but in torpor. And boredom—not tyranny—may be the force that resurrects it.

In other words, if liberal democracy cannot inspire, it may ultimately fail—not because it was wrong, but because it did not feel right.

Conclusion of Part V: Between Triumph and Tragedy

Part V is the book’s most literary and philosophical segment. It completes Fukuyama’s arc by wrestling with the soul of modernity. Yes, we have defeated fascism and communism. Yes, we have extended dignity to more people than ever. But what kind of people are we becoming?

Are we noble citizens—or distracted consumers? Are we morally serious—or emotionally anesthetized? Can a system that promises peace and equality also sustain greatness and meaning?

Fukuyama leaves us with the profound suggestion that liberal democracy is a necessary condition for human flourishing—but not a sufficient one. The structures may endure. But the content—the meaning—must come from us.

And so, the book ends not with answers, but with a question: Now that we are free, what will we become?

3. Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

At the core of The End of History and the Last Man is the provocative claim that liberal democracy is the final ideological form of government. Fukuyama’s argument is intellectually elegant yet controversial. He is not claiming perfection—only finality, an “end point” in the sense that “all the really big questions had been settled”.

But does the evidence match the assertion?

Fukuyama supports his thesis in two dimensions: economic modernization (through the logic of science) and psychological evolution (through the logic of thymos). The economic argument is empirically observable. Liberal democracies are consistently wealthier, more technologically advanced, and more stable over time than their authoritarian counterparts. Moreover, as Fukuyama observes, “no state that values its independence can ignore the need for defensive modernization”. In a Darwinian world of states, those who don’t modernize die.

But the real power of Fukuyama’s thesis lies not in data points but in philosophical reasoning. The struggle for recognition is profound—it feels deeply intuitive. People don’t just want to eat; they want to be seen. To matter. To be remembered. This echoes Plato’s thymos, Rousseau’s amour-propre, Hegel’s struggle for recognition, and even Freud’s ego.

This is where Fukuyama shines: he synthesizes 2,500 years of political thought into a coherent narrative, anchoring the modern democratic project not merely in economics or law but in the human soul.

“Desire and reason are together sufficient to explain industrialization… but they cannot explain the striving for liberal democracy, which ultimately arises out of thymos”.

However, some critics argue that this universalist reading underestimates cultural specificity. Not all societies prioritize the same version of recognition. Fukuyama anticipates this, admitting that:

“The success of liberal politics… frequently rests on irrational forms of recognition that liberalism was supposed to overcome”.

This reflexivity—his acknowledgment of contradiction within his own system—is one of the book’s understated strengths.

Style and Accessibility

Fukuyama’s prose is scholarly but lucid. He assumes an educated reader familiar with thinkers like Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche, yet he also takes time to explain them. His tone is patient, explanatory, and never condescending. Sentences are elegantly constructed, often leading the reader from historical anecdote to philosophical reflection seamlessly.

Take, for instance, this passage:

“People believe that they have a certain worth, and when other people treat them as though they are worth less… they experience the emotion of anger”.

In one line, he connects politics to psychology, bridging the abstract and the intimate.

That said, at over 400 pages, the book can be demanding. Readers unfamiliar with continental philosophy might struggle through sections on Hegelian dialectics or Kojève’s lectures. But this difficulty is justified—it’s a work of ideas, not a beach read.

Themes and Relevance

The book’s primary theme—recognition—has only grown more relevant.

In the 1990s, Fukuyama was focused on communism’s collapse and the liberal democratic wave sweeping Eastern Europe and Latin America. But his theory presciently explains 21st-century phenomena: populism, identity politics, nationalism, culture wars, social media outrage—all are thymotic. They stem from groups who feel unseen, disrespected, degraded.

“The desire to be recognized… leads logically to imperialism and world empire”.

One might say today’s “culture wars” are fought on this very terrain—not over material interests but moral and social esteem.

Moreover, Fukuyama’s warning about the last man rings with chilling clarity in an age of algorithmic escapism, political apathy, and spiritual fatigue. In the comfort of rights and consumption, are we losing the will to strive?

“Is not the man who is completely satisfied… something less than a full human being?”.

His critique, channeling Nietzsche, anticipates the existential void in societies where all needs are met except the need for greatness.

Author’s Authority

Francis Fukuyama’s credentials are unimpeachable. A Harvard-trained political scientist with deep knowledge of philosophy and real-world policymaking, he is both an academic and a practitioner. His argument is not some abstract ivory tower speculation—it’s grounded in decades of global observation and interdisciplinary study.

Still, one can question whether his view leans too heavily on Western liberalism as a universal good. While he addresses critiques of ethnocentrism, his optimism for the liberal order may underplay its internal contradictions—growing inequality, political polarization, and the commodification of the public sphere.

4. Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

1. Intellectual Boldness and Scope

Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man is nothing short of audacious. In a time of global uncertainty—just after the Cold War’s conclusion—he proposed a grand narrative not only of political science but of human nature itself. He didn’t shy away from asking the hardest question in political philosophy: Have we reached the final form of human government?

“The longing that had driven the historical process—the struggle for recognition—has now been satisfied”.

This claim has philosophical lineage (Hegel, Kojeve, Marx), but Fukuyama brings it alive with post-Cold War realism. His scope is vast: from Aristotle to nuclear warheads, from thymos to nationalism. It’s a book that isn’t afraid to think on a planetary, civilizational scale.

2. Revival of Hegel and Thymos

A particularly striking strength is the way Fukuyama reintroduces Hegelian dialectics and thymos into modern discourse. Most political scientists rely heavily on empirical models, materialist analysis, or institutional logic. But Fukuyama dares to suggest that what truly drives humanity is not just economics or rational interests, but the desire to be recognized with dignity.

“Work was also undertaken for the sake of recognition… sustained not so much by material incentives, as by the recognition provided”.

This emphasis on human motivation adds depth to what could have been a dry geopolitical thesis. It’s what allows the book to still feel alive in 2025.

3. Prescient Insight into Identity and Recognition

Fukuyama saw identity politics coming decades before the term dominated headlines. His insight that “recognition” is the engine of history explains why movements today—whether progressive or reactionary—are not merely economic or legal, but symbolic and moral.

When he writes:

“The desire for unequal recognition… constitutes the basis of a livable life”,

he is capturing something essential: that the human desire to matter, to count, to be heard, transcends mere utility. And when denied, it erupts—often irrationally.

4. Balanced Optimism with Caution

Despite the title, Fukuyama is not triumphalist. He anticipates critiques—especially Nietzsche’s charge that liberalism produces a society of hollowed-out individuals who value comfort over virtue.

“Content with his happiness… the last man ceased to be human”.

This dual vision—the peace and progress of democracy versus the spiritual exhaustion it may cause—keeps the book from dogma. It reads not as propaganda, but as philosophical inquiry.

Weaknesses

1. Western-Centric Universality

Perhaps the most frequently raised criticism is that Fukuyama’s universalist framework is too deeply rooted in Western liberal ideals. He contends that liberal democracy fulfills the human desire for recognition—but that assumes a universal definition of recognition.

In non-Western societies, recognition may be more closely tied to family, tribe, faith, or tradition than to rights and individualism. Fukuyama partially acknowledges this:

“Religion, nationalism… have traditionally been interpreted as obstacles to liberalism”.

Yet he tends to see them as stages to be passed through, rather than alternative endpoints.

2. Underestimation of Liberalism’s Contradictions

Fukuyama acknowledges liberalism’s contradictions—inequality, apathy, consumerism—but perhaps underestimates their force. As he writes:

“These problems are not obviously insoluble… nor so serious that they would necessarily lead to the collapse of society”.

But 30 years on, polarization, algorithmic tribalism, environmental crisis, and post-truth politics seem to suggest liberal democracy is under existential pressure not merely from outside, but from within.

3. Weakness of Predictive Authority

Fukuyama is clear: he is not predicting the future but offering a philosophical interpretation. Still, the book has been misunderstood as declaring the final victory of democracy. Critics pointed out the rise of China, Putin’s Russia, Islamic fundamentalism, and right-wing populism as counterexamples.

To his credit, Fukuyama never says history is over in the newspaper sense. He notes:

“There would be no further progress… because all of the really big questions had been settled”.

But the line between normative aspiration and empirical prediction is blurry, and this has led to much misinterpretation—and backlash.

4. Ambiguity Around the “Last Man”

Fukuyama borrows Nietzsche’s image of the “last man”—a complacent, soft, comfort-loving citizen—but the implications are ambiguous. Is the last man tragic? Inevitable? Or even desirable in a stable society? Fukuyama raises the question powerfully:

“Does not the satisfaction of certain human beings depend on recognition that is inherently unequal?”.

Yet he doesn’t fully resolve it. The final chapters leave us in existential ambiguity—which might be intentional, but can also feel unsatisfying.

Reception: Between Applause and Alarm

The book became a global sensation. Fukuyama went from relative obscurity to intellectual celebrity. To some, his work was a triumphant validation of Western liberal values. To others, it was naïve, hubristic, or even dangerous.

One of the early endorsements of Fukuyama’s view came from proponents of democratic peace theory, which posits that established democracies rarely, if ever, wage war on each other. Fukuyama’s optimism was grounded in this line of thinking, supported by data showing a sharp decline in war and violent conflict in the post-Cold War era—especially among nations that transitioned from military rule to democracy.

But the applause was met swiftly by intellectual pushback:

Jacques Derrida’s Postmodern Riposte

In Specters of Marx, Derrida lashed out at Fukuyama’s thesis, seeing it as an ideologically selective narrative designed to bury Marxism. He accused Fukuyama of being a “neo-evangelist” for Western liberal democracy, ignoring widespread suffering, inequality, and exclusion that persisted even under capitalism. Derrida argued that claiming history had ended was not just premature—it was a dangerous obfuscation of ongoing global crises. He famously wrote:

“Never have violence, inequality, exclusion, famine… affected as many human beings in the history of the earth… no degree of progress allows one to ignore that.”

Samuel Huntington’s Civilizational Rebuttal

If Fukuyama imagined a world converging on liberal democracy, Huntington saw a world fragmenting along civilizational lines. His Clash of Civilizations (1996) explicitly responded to Fukuyama, arguing that post-Cold War conflicts would not be ideological but cultural—particularly between the West and Islamic or Sinic civilizations. Where Fukuyama saw consensus, Huntington foresaw chaos.

Benjamin Barber’s “Jihad vs. McWorld”

Another response came from political theorist Benjamin Barber, who warned of a different duality: the homogenizing force of global capitalism (McWorld) versus the fragmenting forces of identity politics and tribalism (Jihad). Fukuyama, he implied, underestimated both.

Islam, Authoritarianism, and the Fragility of Fukuyama’s Framework

Fukuyama’s assertion that radical Islam lacked ideological appeal outside its heartlands was soon tested—and strained—by global events. After 9/11, commentators resurrected The End of History to critique what they saw as the West’s illusion of permanent peace. Fareed Zakaria called it “the end of the end of history.” George Will quipped that history had “returned from vacation.”

Fukuyama defended his position. In a 2001 Wall Street Journal article, he clarified that the “end” of history didn’t mean an end to conflict or tragedy, but that no viable ideological competitor to liberal democracy remained.

Still, critics argued he had underestimated:

- The resilience of Islamic political thought, which includes values like adl (justice), shura (consultation), and maslaha (public welfare)—offering governance alternatives not rooted in liberal individualism.

- The legacies of colonialism and foreign intervention in destabilizing Muslim-majority countries.

- The viability of alternative models—with countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Qatar defying the assumption that only Western models could yield stability.

The Rise of China and Russia: The Return of Alternative Models

In the 2000s and beyond, two geopolitical realities began to chip away at the pillars supporting Fukuyama’s “end of history” thesis: the rise of China as an economic powerhouse under a one-party authoritarian regime, and the increasingly autocratic turn in Russia under Vladimir Putin.

While Fukuyama acknowledged that countries like Russia were only nominally democratic—what political scientists call “anocracies,” regimes that combine democratic and autocratic elements—he maintained that their embrace of the rituals of democracy (elections, constitutions, parliaments) was a backhanded confirmation of liberal democracy’s enduring legitimacy. In other words, even authoritarian leaders pretend to be democrats.

But this explanation began to feel increasingly strained as these states not only gained international clout, but also began projecting alternative governance models with growing confidence. China, in particular, represented a troubling anomaly for Fukuyama’s thesis: a successful, globally integrated capitalist economy coexisting with rigid political authoritarianism. If liberal democracy was supposed to be the endpoint of political evolution, then China’s model looked alarmingly like a detour with momentum.

Political theorist Azar Gat, in his 2007 Foreign Affairs article “The Return of Authoritarian Great Powers”, made this challenge explicit. He argued that the success of Russia and China showed that authoritarian capitalism could be not just viable, but globally influential. Gat’s conclusion was sobering: the future might not belong to liberal democracy after all.

The Post-9/11 World and the Specter of Radical Islam

The attacks of September 11, 2001, marked a seismic rupture in the global imagination—and in the confidence of Fukuyama’s thesis. The notion that ideological conflicts had been resolved seemed, overnight, dangerously outdated.

Fukuyama did address radical Islam in his book. He viewed it not as a viable alternative to liberal democracy, but as a fundamentally local and non-universal ideology. It lacked, in his view, the broad emotional or intellectual appeal that communism or fascism once wielded. He argued that Islamic states—like Iran or Saudi Arabia—were ultimately unstable and would either democratize (like Turkey, in his example) or collapse.

But this analysis failed to capture the deep cultural and political force of Islamic ideologies across the globe, especially in the wake of Western military interventions, economic grievances, and the perceived hypocrisy of democratic regimes. Critics pointed to the enduring influence of Islamic governance concepts—like shura (consultation), maslaha (public interest), and adl (justice)—as signs of a deeply rooted, coherent alternative political philosophy. Nations like Indonesia, Qatar, and the UAE, while not liberal democracies, maintained political stability and strong economies by blending Islamic values with modern statecraft.

The Internal Rot: Political Decay in the Heart of Democracy

In later writings, Fukuyama turned his attention inward—to the cracks forming within liberal democracies themselves. In a series of essays, especially after 2014, he acknowledged what he had not foreseen in the euphoric 1990s: that democracies could backslide. That institutions could decay from within.

He pointed to crony capitalism, political gridlock, and the erosion of public trust as signs of “political decay”—a term he used to describe the breakdown of institutions that once ensured accountability, efficiency, and inclusion. This decay wasn’t just happening in fragile or emerging democracies; it was happening in the United States itself, where rising polarization, populism, and inequality had taken root.

Fukuyama’s own reflections became more tempered. In a 2014 Wall Street Journal column commemorating the 25th anniversary of his original essay, he wrote:

“The most serious threat to the end-of-history hypothesis isn’t that there is a higher, better model… It is that democracies themselves may fail to deliver on their promises of security, prosperity, and opportunity.”

This was a clear shift. It was no longer about defending liberal democracy against external ideological rivals. The rot, he now believed, was endogenous—born from within.

The 2016 Turning Point: Brexit, Trump, and the Rise of the “Post-Fact” World

Two events in 2016 delivered what many saw as fatal blows to Fukuyama’s vision: the Brexit referendum, and the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. These moments were not just about political change—they were signals of an epistemic rupture, what Fukuyama would later call the rise of a “post-fact world.”

In such a world, emotional manipulation, conspiracy theories, and tribal identity took precedence over rational debate, empirical evidence, and institutional trust. Populism surged. Nationalism reawakened. Liberal values—like tolerance, pluralism, and multilateral cooperation—were suddenly on the defensive.

Fukuyama confessed: “Twenty-five years ago, I didn’t have a theory for how democracies could go backward. I do now.”

The implications were clear: the end of history might not have been a destination, but a mirage. Liberal democracy, far from being the culmination of history, might instead be another contingent phase—a form vulnerable to its own success, and to the complacency that success breeds.

Beyond Politics: The Soul of History

Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man is more than a political science thesis about liberal democracy—it’s a meditation on human nature, drawing deeply from the well of philosophy, psychology, and existentialism. This is where many surface-level readings of his book fall short. To understand Fukuyama’s argument in full, one must look past the geopolitical maps and into the inner landscape of the human condition.

At the heart of this landscape is thymos—a Greek term revived by Plato, and later explored by Hegel. Thymos refers to the part of the soul that craves recognition—not simply material satisfaction, but a deep, spiritual affirmation of dignity, status, and worth. Fukuyama believes that this drive, more than economic calculation or survival instinct, is the true motor of history.

So even if liberal democracy satisfies our material needs—food, shelter, safety—it may leave a more essential part of us hungry for meaning. And herein lies the danger.

The Last Man: Nietzsche’s Warning, Fukuyama’s Worry

The second half of the book, often overlooked but vitally important, introduces the concept of “The Last Man”—a term borrowed from Friedrich Nietzsche. The Last Man is not a tyrant, nor a revolutionary. He is, in fact, content. Comfortable. Apolitical. He seeks pleasure, avoids risk, and shuns higher ideals in favor of personal peace and routine.

To Fukuyama, the Last Man is the spiritual byproduct of a world that has eliminated the need for struggle. If liberal democracy triumphs, and if no great ideological battles remain, human beings may atrophy spiritually. They may stop striving for excellence or sacrifice. In Nietzsche’s words, they may become “the most despicable man” because they lack aspiration.

Fukuyama warns us that even if history ends in a material sense, it may not satisfy the deeper demands of thymos. The risk is stagnation—where people, no longer driven by ambition or moral conviction, succumb to boredom, nihilism, or petty tribalism.

And in this psychological vacuum, anti-liberal forces—nationalism, religious extremism, even autocratic populism—can re-emerge, offering the recognition and identity that liberal societies, in their quest for universal equality, sometimes neglect.

The Fragility of Peace and the Return of Struggle

So, paradoxically, the “end” of history contains the seeds of its own undoing. In a society where people have nothing left to fight for, they may invent new battles. Fukuyama believed this was the underlying driver of modern political instability—not ideological disagreement, but the unfulfilled desire for recognition.

We see this today in the rise of populist movements, identity politics, and ideological revanchism. People no longer seek just wealth or safety. They seek respect—for their culture, their nation, their beliefs. This yearning can turn constructive, demanding inclusion and reform. But it can also curdle into exclusion, resentment, or violence.

Fukuyama’s great insight is that liberal democracy can win ideologically and still lose spiritually. It can defeat all external enemies and still fall to internal discontent. The real challenge of history, then, is not merely the establishment of peace, but the preservation of purpose.

Legacy and Reappraisal

More than three decades after its publication, The End of History and the Last Man has not faded—it has mutated. It began as a symbol of post-Cold War triumph. Then it became a punchline in the chaos after 9/11. Later, it became a warning, as democratic institutions began to buckle under pressure from within and without.

Yet Fukuyama’s thesis endures—not because it was final, but because it was open-ended in its very claim of closure. As he clarified time and again, the “end of history” was never about the end of events. It was about the consensus on values. And even that consensus, we now know, is fragile and reversible.

His later writings—on political order, identity, and decay—have shown his continued engagement with the very questions that history keeps asking. He never claimed to have written a eulogy for politics. Instead, he wrote a provocation, and perhaps a philosophical dare: What if we’ve won the argument—but not the heart?

Final Thoughts: The Last Man in All of Us

Reading The End of History and the Last Man today is like encountering a prophecy that has partially come true—but not in the way the prophet expected. Fukuyama captured something real: the appeal, and in many ways the supremacy, of liberal democratic norms. But he also misunderstood the restlessness of the human spirit.

We are not only economic creatures. We are not only rational. We are mythmakers, identity-seekers, and meaning-makers. And as long as we continue to demand recognition—either through justice or rebellion, participation or purity—history will never fully end.

Maybe, just maybe, that’s a good thing.

5. Conclusion

Final Impressions

Reading The End of History and the Last Man today is a sobering, paradoxical, and surprisingly emotional experience. Despite its abstract style, the book isn’t cold—it aches with a question that is as psychological as it is political: Have we finally found the form of government that recognizes us not just as voters, but as full human beings?

Fukuyama’s central claim—that liberal democracy might be the final stage in humanity’s ideological evolution—is not presented with smug certainty. Rather, it is offered tentatively, reflectively, even anxiously, as if Fukuyama himself fears what peace without purpose might mean.

“If contemporary constitutional government… avoids the emergence of tyranny… it would indeed have a special claim to stability and longevity”.

In this, Fukuyama is not celebrating an end, but grappling with what follows: not utopia, but the quiet crisis of the “last man”—a person with rights, equality, peace… and possibly nothing left to strive for.

Who Should Read This Book?

This is not just a book for political scientists. It’s for:

- Philosophers and thinkers pondering the direction of civilization

- Policy makers and diplomats navigating global ideologies

- Social critics and cultural commentators exploring the roots of modern identity crises

- And most importantly, readers who feel a quiet unease with modern life’s comfort and sameness

If you’ve ever asked: Is this all there is?—this book is for you.

It’s a book for anyone disturbed by how easily outrage substitutes for action, how the hunger for validation becomes tribal warfare, and how a society built on freedom may unknowingly breed spiritual listlessness.

As Fukuyama warns:

“The last man had no desire to be recognized as greater than others… without such desire, no excellence or achievement was possible”.

Summary of Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths:

- Visionary synthesis of history, politics, and philosophy

- Revives Hegelian recognition in modern terms

- Prescient diagnosis of identity and cultural politics

- Accessible yet intellectually rich

Weaknesses:

- Western-centric assumptions about universality

- Underplayed contradictions of liberal capitalism

- Ambiguous stance on Nietzschean critique

- Risk of being misunderstood as triumphalist

And yet, perhaps its greatest strength lies in its ability to evolve in meaning. In the 1990s, it was seen as a liberal celebration. In the 2000s, it seemed premature. But in the 2020s and 2030s, it reads like a warning: that the final enemy of democracy may not be communism or fascism, but boredom, numbness, and forgetting why we fought for it in the first place.

Standout Quotes

- “Man does not only desire things, but desires the desire of others.”

- “What drives the whole historical process… is the desire for recognition.”

- “Liberal democracy… provides a gravely defective form of recognition.”

- “The last man ceased to be human.”

Comparison With Similar Works

- Like Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, it balances admiration and warning.

- Like Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, it questions modern man’s contentment.

- Like Marx’s Communist Manifesto, it proposes a directionality of history—but to a different end.