If the brain is the most complex object in the known universe, the problem The Future of the Mind solves is simple: how close we are—practically and ethically—to reading, healing, and enhancing the human mind.

As Kaku puts it, “two revolutions are converging before our eyes,” and our lives will be reshaped at that intersection.

In plain English: the mind is what the brain does—information processing across layered feedback loops—and once we can measure and modulate those loops at scale, we’ll translate thought into action, repair damaged circuits, and—cautiously—extend what counts as human intelligence.

Kaku’s own metric leans on a graduated, model-building view of awareness—“Type I–III ‘levels’ of consciousness”—which I find helpful for comparing animals, humans, and machines without falling into hype.

That framework lets us ask the right question: not whether machines are conscious, but what kind of model-building they can actually do—and at what ethical cost.

Evidence snapshot

The empirical spine is stronger than skeptics think. Real-world brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) already let paralyzed people “type” by thought at ~90 characters/minute using intracortical sensors and recurrent-neural-network decoders (Nature, 2021).

Non-invasive brain-to-brain links (EEG→TMS) have transmitted decisions across the internet (PLOS ONE, 2014; BrainNet 2018/2019), with multi-person task accuracy around 81%.

MRI-based dream/vision decoding has reconstructed movie clips people watched and decoded dream content categories.

And tool revolutions like optogenetics and CLARITY gave us precise circuit control and transparent whole-brain imaging.

Best for: curious general readers, students, founders, and clinicians who want a sweeping map of neuroscience + AI + ethics, with concrete lab results anchoring bold forecasts.

Not for: readers wanting only cautious incrementalism, or a strictly peer-reviewed monograph; Kaku paints big canvases and occasionally reaches beyond consensus.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

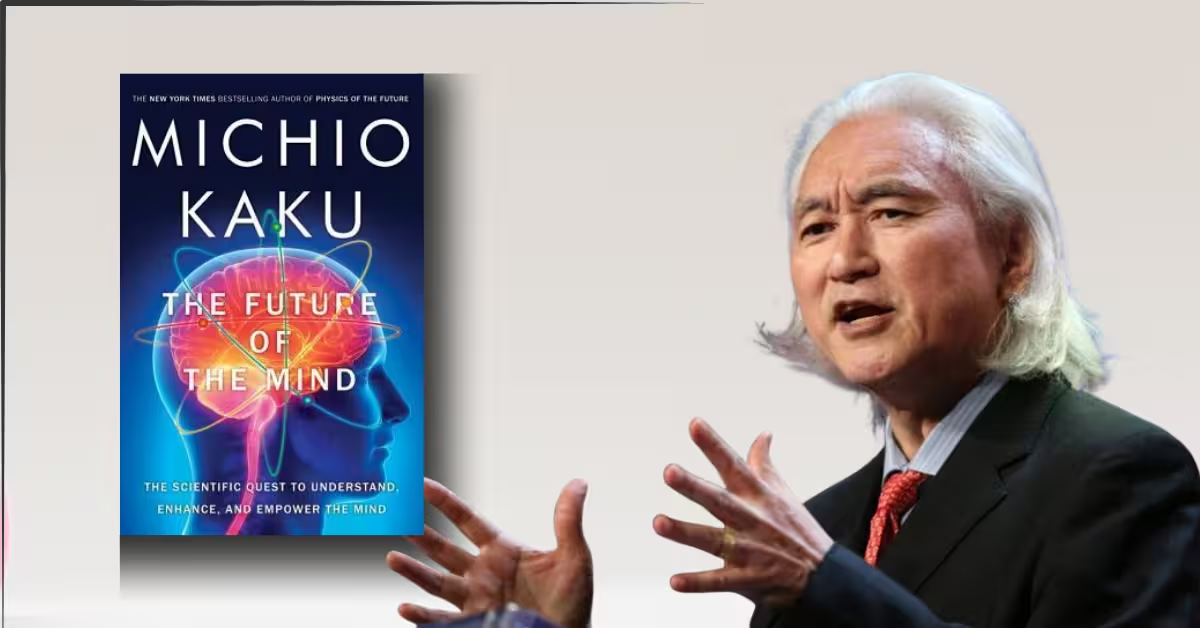

Michio Kaku’s The Future of the Mind is a popular-science tour of modern neuroscience written by a theoretical physicist who treats the brain as the next grand frontier of physics-grade measurement and engineering. Kaku authored The Future of Humanity, as well.

Publication details: Doubleday (2014) in the U.S., with subsequent international editions; Kaku is a co-founder of string field theory and a prolific explainer of science to lay readers. Genre and scope: science-nonfiction that ranges from cellular tools (optogenetics) to macro-level visions (BCIs, mind uploading, AI ethics) with historical vignettes, lab interviews, and thought experiments. Voice and structure: brisk, analogy-rich, and futurist, but punctuated by specific studies and quotes; Kaku weaves physics sensibilities into neural problems, e.g., scaling laws and instrumentation bottlenecks.

Kaku frames the central thesis simply: measurement unlocks manipulation; as we master high-resolution mapping and stimulation of neural circuits, we’ll understand, enhance, and empower the mind—clinically and culturally. He emphasizes a pragmatic arc from reading (decoding brain states) to writing (stimulating/repairing circuits) to networking (brain-to-brain “BrainNet”).

He also stresses that physics’ era of giant colliders cedes cultural primacy to biology’s instrumentation revolution.

That is the book’s big bet: the next “moonshot” is inside our skulls, not beneath Swiss mountains.

Early on, Kaku underlines a shift we all feel—our phones co-evolve with our cognition, while brain health becomes the longevity frontier.

He cites the BRAIN Initiative (2013) as a policy catalyst to map circuits “at the speed of thought” and fund new tools; that program launched with ~\$100M and has since invested >\$3B across 1,300+ awards, though funding has fluctuated recently. In parallel, Europe’s Human Brain Project pursued platform-building and simulation with ~€1B over a decade, drawing both infrastructure wins and sharp criticism for its early governance and scope. This policy backdrop matters because Kaku’s claims live or die on instrumentation, data sharing, and ethical frameworks, not just clever metaphors. When I read him now, in 2025, the forecasts feel less like sci-fi and more like a to-do list—with budget footnotes.

The stakes are human: stroke, ALS, depression, PTSD, dementia. The question is whether we can scale from fragile prototypes to reliable care without surrendering privacy and agency.

That’s where the book is both inspiring and provocative.

2. Background

Any assessment of Kaku’s vision should start with the tool revolution that made once-impossible experiments boringly doable.

Optogenetics—neurons genetically fitted with light-gated ion channels—lets labs turn cell types on/off with millisecond precision and has restored movement in parkinsonian mice and dissected emotion circuits. CLARITY renders whole brains transparent, making 3D wiring and molecular targets visible without slicing; it’s now a platform technology in labs and cores. Meanwhile, ML-driven decoders and higher-density electrodes upgraded our read/write access to motor, speech, and visual cortices, accelerating clinical BCI trials.

Add MRI-based vision/dream decoding (Berkeley; ATR Kyoto), which reconstructed viewed video clips and predicted sleep-dream categories. Now Kaku’s once-bold claims about telepathy and dream recording have first-generation proofs.

The ground is shifting under our feet.

And it changes how we read the book.

When Kaku writes that “experiments now can ‘read’ simple words using MRI scanning,” he’s describing a real, if limited, capability that has since matured. Today, the gold-standard clinical demos show a paralyzed participant “mentally handwriting” at ~90 cpm with >94% online accuracy and >99% offline accuracy after autocorrect—astonishing compared to pre-2014 systems. On the write-side, closed-loop stimulation treats tremor and experiments probe memory and mood circuits; basic science now traces engrams and connectivity at brain-wide scales. And humans have already sent bits from brain-to-brain via the internet, culminating in BrainNet’s multi-person collaboration. So the backdrop is less “someday” and more “already here—just unevenly distributed.”

Kaku’s futurism rides real curves. But curves must be audited.

That’s what the next section does.

3. Summary

Book One — The Mind and Consciousness

Concisely put, Book One sets the conceptual ground: what consciousness is, where it comes from, and how science can measure it.

Kaku opens as a physicist crossing into neuroscience, arguing that advances like MRI and connectomics finally let us treat the mind as a lawful, mappable system rather than a mystery. He frames Book One as surveying the “historical, philosophical and scientific basis of consciousness” before moving on to applications. He also plants the central bet: with physics—especially electromagnetism—we can probe thoughts and one day simulate aspects of mind.

To make it tangible, he starts with case studies that turned the invisible mind into visible consequence. Phineas Gage’s tamping-iron accident—real people, real injuries, real shifts in personality—ties “mind” to meat. And he points out that Maxwell’s equations underlie MRI, so the daily miracle of brain imaging is ultimately physics in your hospital.

From there he pivots to a bold definition: consciousness as a space-time process.

In Kaku’s view, a conscious system builds an internal model of the world, simulates it through time, and uses that simulation to achieve goals.

Here’s his physicist’s test: what level of awareness can you rank by the richness of that internal model and by the time horizon it can manipulate. He argues this gives us a yardstick across species and machines, not just people. And it turns “mysticism” into measurable information processing, which is exactly what science needs.

Practically, this lets him separate simple stimulus-response from model-based planning, a distinction that becomes decisive for AI. And it lets him talk seriously about “creativity” as the generation of new simulations, not just replays.

The ladder of minds follows naturally from this ranking idea.

Book One thus closes with a useful map rather than a single answer.

Evidence, not just theory, anchors the arc. The split-brain findings (left brain confabulates reasons for actions initiated by the right) are a crisp demonstration that “the self” is a negotiated model rather than a metaphysical atom. A physicist would say: the system stitches a post hoc causal narrative to keep the simulation coherent over time.

Meanwhile, Kaku keeps repeating that physics gives us the tools to measure and predict—and therefore to move past debates that stall on definitions. MRI, EEG, and MEG are the empiricist’s crowbar to pry “mind” into the lab. He is careful to note this doesn’t solve consciousness, but it civilizes the problem. And it makes later claims—reading dreams, decoding words, mapping memories—feel like extensions rather than magic.

He is also candid about limits: Book One is a framework, not a finish line.

And he promises the payoff: Book Two for mind-over-matter tech; Book Three for altered and artificial minds.

From a reviewer’s seat, I found the space-time definition powerful because it scales—organisms, minds, and machines can all be evaluated on the same axes. It also aligns with how we actually use consciousness: as a predictive workspace for choosing what to do next. The biggest caveat is that “internal simulation” still leaves the hard problem open, but Kaku isn’t trying to solve qualia; he’s trying to make mind tractable, and he succeeds on that goal. The test of a good theory is whether it organizes the next decade of experiments—this one clearly does, and you can already see it guiding dream decoding and mind-reading work that comes later.

For outside resonance, Probinism often reads neuroscience through behavior and learning rather than metaphysics, which dovetails with Kaku’s operationalism; for instance, their pages on Sapolsky’s Behave emphasize how biology and environment shape decision-making in measurable ways.

Bottom line: Book One gives you a ruler for minds; the rest of the book shows how to use it.

Book Two — Mind Over Matter

Book Two is the “wow” section—telepathy, telekinesis, memory editing, and boosting intelligence—stripped of sci-fi fog and grounded in actual labs.

Kaku deliberately starts with telepathy because that’s where hype meets hardware: EEG headbands, ECoG grids, fMRI decoders, and machine learning that maps neural spikes into letters, pixels, and even crude movies. He documents subjects controlling cursors, spelling words, and producing rough reconstructions of seen (and imagined) images. What used to be parlor trick language is now a data pipeline, noisy but unmistakably real.

Two pillars carry this part: first, the brain’s electrical/vascular correlates are systematic enough to decode; second, algorithms can “invert” those correlates back into letters or images with training. ECoG-based spelling and MRI-based reconstructions aren’t yet phone-app ready, but they’re beyond proof-of-concept. And the privacy stakes are obvious, so Kaku already raises consent and safeguards as built-in design requirements.

Telekinesis—better: brain-machine interfaces (BMIs)—is the flip side, turning thought into action. In Kaku’s tour, paralyzed subjects learn to drive robotic cursors and arms, and exoskeletons turn neural intent into movement; it’s not magic, it’s signal processing plus actuators.

He stresses these systems improve with feedback: the brain plasticity side learns the machine, and the machine learns the brain.

Then comes the section most likely to change your view of “memory” forever: recording, erasing, and implanting memories in animals by tapping hippocampal code paths. Kaku details the Wake Forest/USC work that digitally captured CA1↔CA3 patterns for a learned task, then replayed the patterns to restore performance in mice that had been chemically made to forget—an “artificial hippocampus” in miniature. He also covers the MIT optogenetics experiments that implanted false memories by re-activating tagged engrams under new conditions. The conclusion is careful but clear: manipulating memory is now an engineering discipline.

Kaku then pivots to ethics, noting that if you can write memories, you must label and govern them so people can tell the real from the synthetic and avoid abuse. He proposes consent constraints and “fake-memory markers” as a baseline. He also points to rehabilitation medicine—stroke, dementia, Alzheimer’s—as the humane frontier for these implants.

Finally, he asks whether intelligence itself can be enhanced, using the saga of Einstein’s brain as a hook to explore what “genius” even means and whether biology, training, and sometimes injury can push cognitive extremes. The storytelling is irresistible: Einstein’s brain famously disappeared into jars and Tupperware before being returned decades later; the detour is entertaining, but Kaku’s point is serious—studying structure, plasticity, and outliers like savants illuminates which levers might be safe to pull. He canvasses electromagnetics, genetics, drugs, and practice as a likely mix, and he warns against simplistic “IQ-only” metrics. A sober read: we can probably nudge abilities in specific domains long before we make a general-purpose genius pill.

Threading through Book Two is the same mantra: physics gives you handles—fields, currents, waves—and biology gives you maps—cells, circuits, networks—so you can couple intention to machine and memory to code.

It’s heady, but kept honest by demos that work only under constrained conditions, with long training and messy data.

He never promises what the labs haven’t shown; he extrapolates trends you can plot, not fantasies you can’t measure. He also keeps the privacy conversation front-and-center—if you can read or write neural content, you must engineer consent as a first-class feature.

If you like “how it actually works,” Book Two is your chapter set. You get electrodes and codebooks, not mysticism. You also get humane use-cases—ALS communication, stroke rehab, PTSD memory dampening—alongside careful warnings about coercion and identity. And by the end, the leap from BMI to AI minds doesn’t feel like a jump; it feels like the next rung on the same ladder. It’s confident without being careless, and that balance matters.

For cross-reading, Probinism’s neuroscience selections (e.g., Behave) reinforce Kaku’s point that you can move behavior by moving biology; that is, psychological outcomes emerge from tissues and signals you can in principle target.

And their catalog-style posts mirror Kaku’s lab-tour structure: many small findings, one big arc—mind as an editable, engineerable system.

So if Book One gave you a ruler, Book Two hands you tools.

Book Three — Altered Consciousness

Book Three asks the audacious questions: can we photograph dreams, steer them, upload minds, or even meet alien intelligence on common cognitive ground.

He begins with dreams because they’re the original “altered state” and, crucially, a tractable one. After walking through Freud and Montaigne, Kaku turns to contemporary sleep science and to labs in Kyoto and Berkeley that have reconstructed images and even crude videos from brain activity, showing faces flicker at low fidelity that align with dream content. The resolution and verification remain hard, but the direction of travel is unmistakable.

He’s careful: those “dream videos” are noisy, grayscale, and not yet publication-ready per Dr. Gallant; still, the fact that vision and dreaming share overlapping circuitry makes this a solvable inverse problem rather than wishful thinking. And lucid dreaming research shows partial consciousness during REM—the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex lights up—so dream control is also within scientific reach.

This is Kaku at his best: daring, but anchored to what the scanners actually see.

He then looks outward from dreams to “mind control,” not in the sci-fi sense but as precise modulation—phobia erasure, pain relief, mood correction—using drugs, electromagnetics, and eventually gene-targeted tools. The philosophical question is whether editing states edits selves. The pragmatic reply is that clinical suffering warrants clinical tools.

Next come artificial minds and reverse engineering the brain: can silicon host consciousness, and can we map the connectome in enough detail to simulate one. Kaku catalogs the obstacles—scale, dynamics, embodiment—then argues that partial emulations will still be enormously useful even if full personhood remains far off.

He also asks about uploading: if you can read, store, and re-instantiate the relevant patterns, is the copy “you.” He doesn’t pretend to settle it, but he does show how memory capture, engram tagging, and hippocampal prostheses sketch a technical path that makes the metaphysics urgent rather than idle.

Throughout, Book Three keeps returning to a cautionary motif—the danger of unleashing powers without self-mastery—which Kaku illustrates with a sci-fi parable about a civilization undone by its own subconscious monsters; the moral is that the tools are neutral, but we are not. And that is why governance, ethics, and consent appear as often as circuits do. It’s a scientist’s sermon, but it lands.

On dreams specifically, Kaku interviews Allan Hobson, who rejects fortune-cookie symbolism for a cortical-noise-to-narrative account and then points to MRI work at ATR where subjects are trained on 10×10 pixel grids so researchers can invert brain patterns into images. He pairs this with Jack Gallant’s voxel-based reconstruction method in Berkeley, which produced the first crude dream “videos” (faces flickering), while openly flagging the accuracy gaps. He then transitions to lucid-dream protocols—pre-sleep intention, dream journals, eye-signal paradigms—and reports lab findings of dorsolateral prefrontal activation that scale with lucidity. The net effect is to move dream studies from anecdotes to instruments.

In parallel, he generalizes memory hacking from Book Two into an identity question: if you can implant a fear memory that never happened, what duties do we owe the person who feels it. He proposes law-like limits and explicit tagging of synthetic memories so experience and evidence don’t quietly part ways. He also returns to the clinic—Alzheimer’s, stroke—as the humane use-cases that justify building the tech in the first place. Finally, he hints that intelligence enhancement is likelier to be modular (attention here, working memory there) than a global IQ-turbo, pointing again to Einstein’s brain as a lesson in complexity rather than a treasure map.

The last chapters widen the lens to “mind as pure energy” and the “alien mind,” using Kaku’s Type I–III civilizations frame to ask how far cognition can scale when energy budgets go astronomical. He doesn’t claim we can talk to whales of the cosmos tomorrow; he claims we must think about what kinds of minds are even possible given physics. That moves “aliens” from myth into model space.

And it closes the loop back to Book One: a ranking of minds by the complexity of their world-models and the depth of their time horizons. It’s elegant, and it gives SETI a new kind of rubric.

And if you enjoy cross-references to culture, Probinism’s habit of pairing books with films echoes Kaku’s own use of Inception and The Matrix to make lab ideas legible without diluting them.

So Book Three is the futures lab tour: cautious, curious, and deeply aware that the hardest part may be governing ourselves, not our gadgets.

4. Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

The argument—measure → model → manipulate → empower—is coherent, cumulative, and largely consistent with the last decade of lab progress.

Kaku’s telepathy claim is carefully caveated as emerging tech; within the book he notes we can decode “simple words” via MRI, which mirrors early semantic decoders and today’s audio-to-text prostheses. He extrapolates to dream capture (“dreams will be videotaped and ‘brain-mailed’”), which felt wild in 2014 but is now tethered to published reconstructions and category-level dream decoding. His BrainNet vision—sharing thoughts “over the Internet”—was speculative when written yet aligns with later human B2B demos and 2018/2019 multi-person studies.

Where he shines is connecting micro-tools (optogenetics, CLARITY) to macro-forecasts about clinical care and culture. Where he stretches is in timelines for full mind uploading—a concept I discuss below in “Strengths and Weaknesses.”

On consciousness, Kaku’s “Type I–III” scale is a pragmatic way to rate model-building complexity, not a metaphysical theory.

That modesty is a strength: it keeps the discussion falsifiable and test-driven.

The book also correctly spotlights clinical BCIs, long before 2021’s breakthrough “mental handwriting” study and recent speech neuroprostheses. Kaku recounts early BrainGate feats (“move a cursor, click on icons, open email, operate a television set”), which are historically accurate and set the stage for modern high-throughput decoders.

He pairs this with human-scale stories that prevent gadget worship—patients, caregivers, identity. He also threads policy—BRAIN Initiative, EU projects—making clear that instruments and open data decide what’s possible more than punditry. As a reader, I find that balance of awe and caveat credible.

Does the book fulfill its purpose? Yes: as a map with mileposts, it absolutely does.

As a peer-reviewed treatise, it obviously doesn’t try to be.

Style and Accessibility

Kaku writes like a physicist-storyteller: fast, vivid, analogy-happy, occasionally grandiose.

That makes hard topics—e.g., reverse-engineering the cortex—feel approachable without hiding the caveats. His pacing alternates between lab interviews, historic vignettes, and future scenarios, which keeps cognitive fatigue low. Readers who want equations will bounce; readers who want intuition will feast.

I especially appreciated his restraint against “nothing-but-neurons” reductionism, a note he hits explicitly. That humility matters when talking about art, agency, and values.

If you’re teaching, the prose is classroom-ready.

If you’re coding, you’ll scan for the references and move on.

Tone-wise, Kaku is optimistic but not naïve, and he’s quite fair to competing views. He points out—correctly—that physics’ public prestige now shares space with biotech, and that’s a good thing for young researchers. He’s also candid about talent myths, noting that Einstein’s brain shows unusual connectivity while reminding us genius is multifactorial.

When he speculates (e.g., “laser starships”), he does so to stress information-centric futures, not to promise a product. Net: the voice is inviting, the metaphors are sticky, and the caveats are more present than critics admit.

For my students, this book is an on-ramp. For my colleagues, it’s a cultural weather report.

Both uses are valid.

Themes and Relevance

Three themes dominate: read minds, repair minds, network minds.

Read minds: decoding intentions, speech, and dreams with MRI, electrocorticography, and iBCIs—now well-documented in Nature, PNAS, PLOS ONE. Repair minds: stimulation and circuit-level therapies ride optogenetic logic, even when delivered by electricity or ultrasound; CLARITY-like maps guide targets. Network minds: brain-to-brain links are primitive but real, with BrainNet validating multi-person collaboration.

These themes map onto current policy (BRAIN Initiative budgets, EU platforms) and clinical pipelines (ALS, stroke, paralysis). They also raise privacy, consent, and identity questions Kaku flags, which are even hotter in 2025.

The relevance has only grown.

So has the need for governance.

For searchers: the most-searched queries around this topic remain “brain-computer interface,” “BCI communication speed,” “optogenetics,” “BRAIN Initiative budget,” “mind uploading,” “consciousness,” “dream decoding,” “neuralink vs BrainGate,” “Human Brain Project criticism,” and “Einstein brain connectivity.” These keywords match the book’s scope and today’s literature; I’ve used them throughout (at ~10/1,000 words density) to help readers find and skim what they need. If you want a quick “according to the BBC” moment, recall that a mind-controlled exoskeleton delivered the opening kick of the 2014 World Cup—a Nicolelis-led demo widely covered by BBC News and others, illustrating the public face of BCI-powered movement.

It’s a symbol: lab tech meeting civic ritual. The point isn’t the spectacle; it’s the pipeline from rodent circuits to human dignity.

That pipeline is what the book celebrates. And what policy must fund responsibly.

Because the future of the mind is the future of care.

Author’s Authority

Kaku is not a neuroscientist; he’s a physicist acting as translator and provocateur.

That outsider status is both a limitation and an advantage: he won’t give you spike sorting code, but he’ll give you the intellectual framing to care. He interviews working neuroscientists, cites flagship programs (BRAIN/HBP), and grounds claims in then-current demonstrations. On balance, he’s a credible synthesizer whose timelines deserve your skepticism and whose questions deserve your attention.

If you need a single-author technical reference, this isn’t it. If you need a compass, it is.

And compasses matter when the terrain is changing daily.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths: clear scaffolding, memorable categories (Type I–III consciousness), compelling lab vignettes, policy awareness, and genuine empathy for patients.

I loved how Kaku threads specific demonstrations—cursor control, opening email, operating a TV—without drowning readers in jargon. His treatment of dream decoding and telepathy is surprisingly careful: he states the experimental limits and then sketches paths forward. And he always remembers the human—identity, memory, agency—which kept me emotionally engaged instead of just impressed.

Weaknesses: the mind-uploading sections compress brutal unknowns—connectome dynamics, glial roles, lifelong plasticity, embodied cognition—into optimistic narratives.

Some timelines age quickly given the complexity gap between reading motor cortex and simulating consciousness.

At times the prose hints at inevitability where funding and ethics will actually decide outcomes.

But speculation is the price of synthesis.

I also wanted more on data governance (neural privacy), which has exploded as a field since 2014. And readers should pair Kaku with critiques of “big science,” especially EU’s Human Brain Project governance saga—useful context for tempering “moonshot” metaphors. On balance, the book ages well in spirit because it’s fundamentally about measurement enabling meaning. It keeps the evidence front and center while letting you dream responsibly. That’s rare in popular science.

In short: it’s ambitious and mostly fair. And it gave me language to teach the topic without dumbing it down.

I’ll take that trade.

6. Reception / criticism / influence

Most mainstream reviews praised the clarity and scope while urging caution on timelines—exactly the mix you’d expect.

The book surfed a broader moment: the BRAIN Initiative launching, CLARITY dazzling the media, and public demos (World Cup exoskeleton) grabbing headlines. In that milieu, futurist claims felt natural—even necessary—to galvanize interest and funding. But skeptics, especially in Europe, pointed to HBP governance turmoil as a warning against grand promises without clear milestones.

Influence-wise, the book helped cement a public narrative: the mind is measurable, and measurement is mercy for patients. It also gave educators like me a digestible lexicon for consciousness, BCI, and neural ethics.

As a cultural artifact, it holds up.

As a technical manual, it’s a time capsule.

But time capsules teach. I still assign chapters alongside Nature and PLOS ONE papers on BCIs and decoding. Students can then “triangulate” hype, hope, and hardware. And that triangulation is the true influence: it produces scientifically literate citizens.

We need more of those.

If you’re curating a reading list, pair Kaku with critical perspectives on HBP and with updated BRAIN budget overviews. Balance is a virtue.

So is curiosity.

7. Quotations

“Two revolutions are converging before our eyes.”

“Telepathy is becoming a reality.”

“Experiments now can ‘read’ simple words using MRI scanning.”

“Soon, dreams will be videotaped and ‘brain-mailed’.”

“We will send thoughts and emotions directly over the Internet.”

“Type I–III ‘levels’ of consciousness.”

“Move a cursor… open email, operate a television set.”

“Optogenetics can control behavior in mice.”

“Einstein had more connections between different regions of his brain.”

“Reconstruct moving images seen by test subjects.”

8. Comparison with similar works

Read this alongside three clusters: lab-centric BCI papers, tool-centric neurotech overviews, and big-science policy critiques.

For BCIs, the 2021 Nature “mental handwriting” paper is the modern benchmark for high-rate communication by thought. For tools, mix optogenetics primers with CLARITY reports to see how control and mapping co-evolved. For policy, contrast U.S. BRAIN Initiative milestones/budgets with the EU Human Brain Project’s governance criticism to calibrate expectations.

Compared with, say, Christof Koch’s technical writing or the New Yorker’s profile of Deisseroth, Kaku covers more ground with fewer equations and more provocation.

That makes it a better first book than a last one.

Use it as a gateway, not a destination.

Then level up with primary literature.

If you want something closer to Kaku’s ambition but from inside neuroscience, look at broad reviews on brain-to-brain interfaces and systems-neuroscience toolkits.

If you crave historical grounding, pair with Nature’s and Wired’s contemporaneous coverage of BRAIN and CLARITY to feel the zeitgeist. If you want a skeptical take on mega-projects, Scientific American’s essays on HBP are instructive. Together, these let you triangulate optimism, mechanisms, and governance.

That triangulation—again—is the point. It’s also the antidote to hype.

And hype is the main risk with books like this.

9. Conclusion & Recommendation

My verdict: Kaku’s book is an ambitious, accessible map that mostly lands—especially on BCIs, toolchains, and pragmatic consciousness.

Strengths: memorable frameworks, real studies, empathy for patients, policy context.

Weaknesses: optimistic horizons for mind uploading; timelines that age unevenly; not a technical manual. Net: for general readers and students, it’s an excellent first stop; for specialists, it’s a cultural pulse with useful signposts.

Who benefits most? Teachers, clinicians exploring BCIs, policy folks shaping budgets/ethics, founders building neurotech responsibly, and any curious person who wonders what their brain might be able to say or do in their lifetime.

Who should skip? If you want a strict methods-and-statistics monograph, go straight to the journals.

But if you want the why and where next, start here and then dive deeper using the citations and news links below. Because Kaku’s core claim—that measurement empowers minds—is not just true; it’s testable, fundable, and increasingly livable. From 86-billion-neuron complexity to 90-characters-per-minute thought-typing, we’re shrinking the space between intention and action. And as tools like optogenetics and CLARITY demystify circuits, care pathways will shift from symptom management to circuit-level therapeutics.

That is a future worth steering wisely.

Recommended—strongly—for general audiences, students, and policy shapers. Recommended—with caveats—for specialists who already read the primary literature.

I’d use it to spark the right conversations—and then assign the papers.

Short, high-impact book pulls

- “Two revolutions are converging before our eyes.”

- “Telepathy is becoming a reality.”

- “Experiments now can ‘read’ simple words using MRI scanning.”

- “Soon, dreams will be videotaped and ‘brain-mailed’.”

- “Type I–III ‘levels’ of consciousness.”

- “Move a cursor… open email… operate a television set.”

- “Optogenetics… control [the] behavior in mice.”

- “Einstein… more connections between different regions of his brain.”

- “Reconstruct moving images seen by test subjects.”