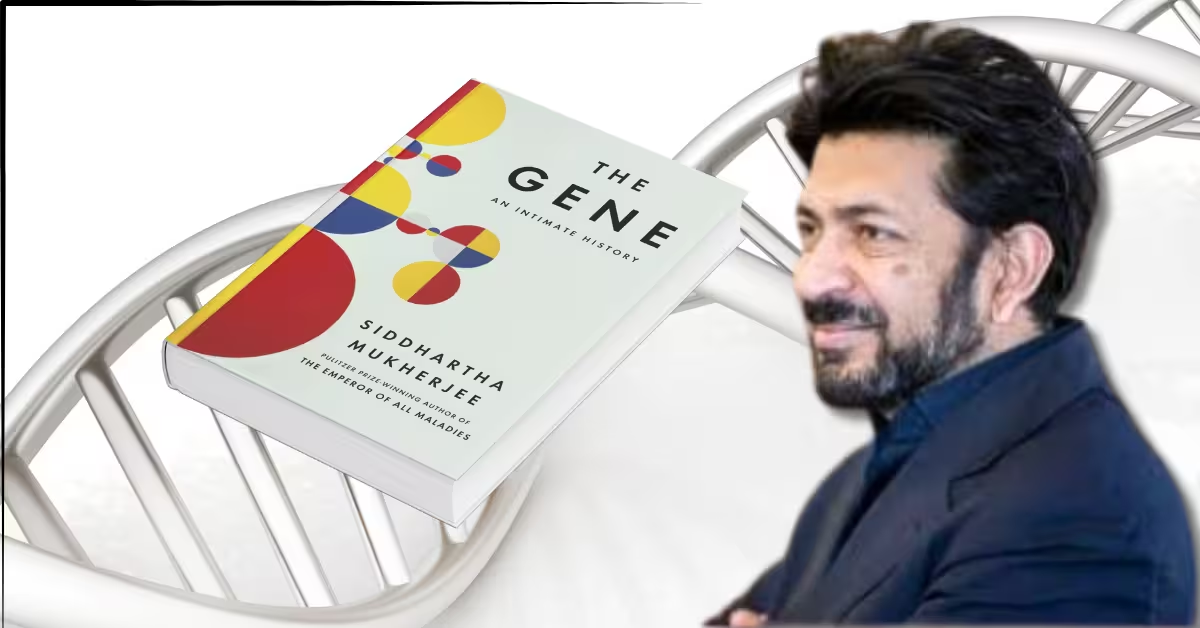

The Gene: An Intimate History is more than a sweeping account of genetics; it’s a deeply personal journey into the biological essence of human identity. Written by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Siddhartha Mukherjee — a physician, researcher, and author of the acclaimed The Emperor of All Maladies — this monumental work blends medical history, family memoir, and cutting-edge science to explore how genes shape everything from behavior and disease to fate and identity.

Mukherjee’s dual role as both scientist and storyteller gives him a unique vantage point. He not only traces the scientific breakthroughs in molecular biology but also reflects on his own family’s struggle with mental illness. This dual perspective turns the study of the gene into what he calls “an intimate history” — of science, of family, and of the self.

At its core, The Gene presents a powerful and cautionary thesis: while our genes are the blueprints of our being, they are not our destiny.

Mukherjee’s argument is layered. On one hand, he emphasizes the profound influence of heredity on identity, disease, and behavior; on the other, he warns against deterministic thinking, which historically paved the way to eugenics, genetic discrimination, and ethically fraught attempts to ‘perfect’ humanity. It is one of the 100 best non-fictions books ever written.

He writes, “This book is the story of the birth, growth, and future of one of the most powerful and dangerous ideas in science: the gene” (Mukherjee, p. 26).

Table of Contents

Background

Before understanding Mukherjee’s narrative, it’s essential to appreciate the intellectual and historical terrain he covers. The Gene follows a tradition of scientific storytelling that includes works by Richard Dawkins (The Selfish Gene) and James Watson (The Double Helix), but it is perhaps more ambitious in scope and personal in tone.

Mukherjee traces the idea of heredity from Aristotle to Mendel, from Darwin to the Human Genome Project, and into the ethical quandaries of CRISPR gene editing. In doing so, he does not shy away from uncomfortable truths — including how scientific ideas have been co-opted by fascist ideologies, particularly during the Nazi regime.

But what distinguishes The Gene is its grounding in personal history. Mukherjee’s family has long grappled with mental illness. This inherited legacy haunts the book’s emotional landscape and raises pressing questions about the genetic roots of psychological disorders.

“I had not just a theoretical investment in genetics,” Mukherjee admits, “but a personal one. The weight of heredity was not an abstraction for me” (Mukherjee, p. 19).

Summary

Prologue: Families

In The Gene: An Intimate History, Siddhartha Mukherjee opens the narrative with a deeply personal lens, tracing the shadows of heredity within his own family. This prologue does not merely serve as a memoiristic flourish—it lays the thematic groundwork for what will become an epic chronicle of human identity through the prism of genetic inheritance.

Mukherjee recounts a poignant visit in 2012 to his cousin Moni, institutionalized for schizophrenia. “Since 2004, when he was forty, Moni has been confined to an institution for the mentally ill…with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. He is kept densely medicated—awash in a sea of assorted antipsychotics and sedatives…”. This episode becomes a harrowing metaphor for the burdens and ambiguities of genetic fate.

The story also bears the emotional weight of the author’s father—who refuses to accept Moni’s diagnosis. His denial is deeply rooted in fear: a tacit recognition that madness—“like toxic waste”—may run through their family’s genetic fabric. In Mukherjee’s words: “Madness, it turns out, has been among the Mukherjees for at least two generations”.

This family history launches the book’s central tension: How much of who we are is predestined by the gene? Mukherjee situates his father’s resistance as a psychological response to heredity’s cruel impartiality—where love and character cannot always outmaneuver DNA’s blueprint. The inheritance of illness here is not abstract—it is heartbreakingly intimate.

Mukherjee deploys vivid prose to humanize what could easily descend into cold clinicality. The prologue’s two key emotional fulcrums—Moni’s silent institutionalization and the author’s father grappling with guilt and grief—exemplify the text’s hybrid nature: part science, part story. This tension is crystallized in lines like, “some kernel of the illness may be buried, like toxic waste, in himself,” which elevates the gene from a biological unit to an existential force.

The author sets out to confront a paradox: Genes are deterministic, yet identity is irreducible. This inquiry begins not in a lab but in a home touched by suffering. As he writes: “The gene is one of the most powerful—and dangerous—ideas in science,” and this is not a dispassionate statement. It is a warning born of generational trauma.

Mukherjee hints that his exploration will not settle for mechanistic reductionism. He opens the book with two poetic epigraphs—one from The Odyssey: “The blood of your parents is not lost in you,” and another from Philip Larkin: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.” These contradictory perspectives—ancestral pride and parental betrayal—frame the dual legacy of genetics as both inheritance and affliction.

This prologue immediately connects readers to the book’s humanist ambition: to bridge the scientific with the soulful. Mukherjee will go on to describe Watson and Crick, recombinant DNA, and the Human Genome Project—but always with a sense that behind each gene is a person, and behind each mutation, a life altered.

The prologue achieves more than narrative engagement—it signals the methodological stance of the book: genetics, while technical, must never lose its intimacy with history, society, and psychology. The Gene is not just a record of science—it is a confrontation with destiny.

Part One: The Missing Science of Heredity (1865–1935)

In the inaugural chapter of his chronicle, Siddhartha Mukherjee reconstructs a critical blind spot in the history of science: the “missing science” of heredity. Between 1865 and 1935, genetics as we now understand it was an unformed shadow of biology—its fundamental laws overlooked or misunderstood by scientists for nearly a century.

The Rediscovery of Mendel

Mukherjee begins with Gregor Mendel, the Moravian monk who, in the cloisters of his monastery garden, performed what would later be considered the first controlled genetic experiments on pea plants.

As Mukherjee writes, “Mendel’s pea plants… revealed that inheritance followed precise mathematical patterns—ratios that could be counted, tabulated, and predicted”. Yet, in a scientific world dominated by the more chaotic notions of blending inheritance, Mendel’s laws were ignored, and his work was forgotten.

It wasn’t until 1900, long after Mendel’s death, that his papers were rediscovered independently by three European botanists: Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak. This rediscovery ignited the flame of modern genetics. The central insight—that traits are inherited as discrete units, now called genes—was as revolutionary as Darwin’s theory of evolution, though it had existed in parallel, unrecognized.

Genetics vs. Evolution

Mukherjee carefully traces the tension between Darwinian evolution, which emphasized slow, continuous variation, and Mendelian genetics, which emphasized discrete, binary outcomes (tall vs. short, yellow vs. green). “Darwin’s theory had no mechanism for the unit of heredity,” Mukherjee notes, “and Mendel had no framework for evolution.” The two ideas were mathematically and conceptually incompatible—until the synthesis decades later.

This rift also signaled a deeper issue in early biology: no shared vocabulary, no guiding conceptual framework. Without the word “gene” or knowledge of DNA, scientists were groping in the dark. As Mukherjee puts it, “the gene was an idea in exile.”

Eugenics: A Dark Detour

Perhaps the most chilling chapter of this period is Mukherjee’s examination of eugenics, which he characterizes as genetics without knowledge and compassion.

Lacking a rigorous understanding of heredity, early 20th-century social scientists and physicians in the U.S., Britain, and Nazi Germany weaponized the idea of genetic purity. “In America, sterilization programs targeted the ‘feeble-minded,’ epileptics, and the poor,” he writes. By the 1930s, over 60,000 Americans had been sterilized by state-sanctioned eugenics programs.

Mukherjee devotes considerable attention to Carrie Buck, whose coerced sterilization in Virginia led to the infamous Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. chillingly wrote, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough,” legitimizing forced sterilization in the name of public health. It was a catastrophic misuse of nascent genetic science, and a warning that genetics without ethics is tyranny.

The Chromosome Theory and the Birth of Cytogenetics

In contrast to the pseudoscientific chaos of eugenics, real progress was made in the emerging field of cytogenetics—the study of chromosomes. Pioneers such as Thomas Hunt Morgan used the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) to show that genes reside on chromosomes, which follow precise, observable patterns during reproduction. Morgan’s lab would become the crucible of modern genetic mapping.

The fruit fly, Mukherjee writes, became a sort of “aerial paper doll for genetic dissection.” By 1915, Morgan and his team had mapped the first linear genetic map of a chromosome—evidence that traits were not only linked to genes but that genes were physical entities that could be tracked and manipulated.

This represented a crucial shift: from abstract statistical models to molecular physicality. From this point forward, the gene was no longer just a mathematical ghost—it had a body, a place, and eventually, a chemical structure.

The Concept of the Gene

By the 1930s, the idea of a gene as a unit of heredity had crystalized, even if its molecular nature remained mysterious. As Mukherjee explains: “The gene had become something between an abstract idea and a physical object—like a particle in quantum mechanics.” It could be inferred through its effects but remained invisible to the naked eye.

Yet despite these advances, crucial questions remained unanswered: What are genes made of? How do they replicate? What mechanisms turn genes on or off? These puzzles would not begin to unravel until the biochemical revolution of the 1940s and 50s.

Part Two: In the Sum of the Parts, There Are Only the Parts (1930–1970)

This part of The Gene explores a pivotal transformation in biology—when genetics transitioned from an abstract conceptual model to a molecular science.

The title itself, taken from Wallace Stevens’s poetic line—“In the sum of the parts, there are only the parts”—acts as both a challenge and a metaphor: can we truly understand the whole of human identity by understanding its parts, namely, the gene?

From Particles to Molecules

Mukherjee shows how scientists, still uncertain of the exact chemical composition of the gene, began interrogating the biological material itself. Was the gene made of proteins, as most biologists assumed due to their complexity, or of nucleic acids, which seemed too simple?

The debate culminated in the famous Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment (1944). Using Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria, Oswald Avery and his colleagues demonstrated that DNA, not protein, was the hereditary material. “This was biology’s equivalent of splitting the atom,” Mukherjee writes—confirming that the gene had a chemical basis and launching the modern era of molecular genetics.

This breakthrough laid the groundwork for one of the most revolutionary scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

The Double Helix: DNA’s Structure Revealed

Mukherjee’s narrative then turns to the now-mythologized discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick, aided by Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray crystallography. In one of the most iconic moments in science, Watson saw Franklin’s Photograph 51, an image of DNA’s helical structure, and within hours, he and Crick sketched the now-familiar double helix on a scrap of paper at a pub in Cambridge.

DNA, Mukherjee writes, was not just a “passive thread of heredity”—it was a code, a language composed of four chemical letters (A, T, C, G), capable of storing and replicating information. “The double helix was not just a structure—it was a logic,” he notes. This logic governed the replication of life.

In 1961, Marshall Nirenberg and Heinrich Matthaei deciphered the first “word” in the genetic code—demonstrating how DNA translates into proteins via RNA. This moment marked the birth of the central dogma of molecular biology: DNA ➝ RNA ➝ Protein. This flow of genetic information became the unifying theory of life itself.

Genes, Brains, and Behavior

As the molecular code unraveled, so too did a surge in ambitions. Could genes explain everything about an organism, including the mind?

Mukherjee explores the work of Seymour Benzer, who attempted to map the genetic origins of behavior using fruit flies. Benzer discovered that certain flies with mutated genes would sleep differently, showing that even “something as elusive as a biological clock could have a genetic basis”.

However, Mukherjee is careful to temper genetic determinism. He emphasizes that while genes may establish predispositions, they do not lock identity into a prison. “Genes are like the script of a play,” he writes, “but it is the performance—context, environment, interaction—that gives it meaning.” This is a major thematic tension throughout the book: what is written vs. how it is read.

The Rise of Genetic Engineering

With DNA’s structure and code deciphered, scientists sought to manipulate genes themselves. Mukherjee details the breakthrough of restriction enzymes in the 1970s—molecular “scissors” that could cut DNA at specific sites.

This gave rise to recombinant DNA technology, where genes could be spliced and combined across species. For the first time in history, it became possible to create genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The implications were staggering: drugs like insulin could be mass-produced, and traits could theoretically be inserted into future generations.

But the science provoked fear. At the Asilomar Conference of 1975, scientists and ethicists debated the implications of this new power. Could we create biological monsters? Could this become a new eugenics?

Mukherjee captures the uncertainty: “The gene was no longer a lens for looking into the body—it had become a lever for altering it.”

Reductionism and Its Limits

Part Two also critiques biological reductionism—the belief that genes alone define human traits. Mukherjee acknowledges the temptation to believe in a genetic essentialism: that violence, genius, sexuality, even faith can be traced back to DNA.

But this belief, he warns, is seductive and dangerous. “In the sum of the parts,” he quotes again, “there are only the parts.” Understanding genes is essential, yes—but reducing humanity to genes is a fallacy. Genes do not operate in isolation; they respond to networks, environments, and histories. To look only at the parts is to miss the miracle of the whole.

Key Takeaway:

This section reveals the triumph and the tension of molecular genetics: the gene is no longer a theoretical unit—it is a chemical, a code, a tool. Yet with this knowledge comes a seductive illusion—that all of life is decipherable, editable, controllable. Mukherjee resists that reduction, reminding us that science, like the genome, must be read in context.

Part Three: The Dreams of Geneticists (1970–2001)

This section of The Gene is both a celebration and an examination of ambition—the era where the theoretical power of genetics began to meet technological capability. Titled “The Dreams of Geneticists,” it surveys a historical moment when scientists began to believe they could not only understand the gene but master it—map it, edit it, and use it to cure disease.

Mukherjee calls it “a time of biological euphoria,” but just beneath the optimism lies his persistent ethical refrain: what happens when scientific dreams outpace wisdom?

The Rise of Biotechnology

The part opens in the 1970s with the emergence of genetic engineering—a phrase that once belonged in science fiction. The invention of recombinant DNA technology enabled scientists to combine genetic material from different organisms. As Mukherjee writes, “The gene had become portable. It could be copied, snipped, pasted, and carried into new genomes.”

Key to this transformation was the collaboration between Herbert Boyer and Bob Swanson, which led to the creation of Genentech, the first true biotech company. Their initial success was synthetic insulin, genetically engineered in bacteria—ushering in an era of molecular medicine.

Mukherjee notes that this shift also marked a shift in science’s social contract. “The gene had moved from monasteries to markets,” he writes, hinting that biological inquiry was no longer solely a philosophical pursuit—it was now a commercial venture.

The Human Genome Project: Mapping the Self

The ultimate dream of 20th-century genetics, Mukherjee suggests, was to map the entire human genome. The Human Genome Project (HGP), launched in 1990 and concluded in 2001, aimed to catalogue all ~20,000–23,000 human genes. It was, as Mukherjee writes, “biology’s moonshot.”

This was not merely an act of discovery—it was an act of self-discovery. Francis Collins, director of the HGP, called it a “book of life,” and Mukherjee underscores the metaphor: “We had written the first draft of our own instruction manual.”

The project revealed several unexpected truths:

- The human genome contained far fewer genes than expected—around 21,000, not hundreds of thousands.

- Genes were shared across species: humans share 60% of genes with fruit flies and 98.7% with chimpanzees.

- Much of the genome was non-coding DNA, dismissed at the time as “junk DNA”—a term later challenged.

Mukherjee treats this moment with intellectual humility: “The genome had been mapped, but not understood.” Knowing the letters in a book doesn’t mean you can comprehend the story.

Genes and Disease: The Search for Causality

With the HGP in full swing, attention turned to disease-linked genes. Researchers began identifying single-gene disorders—like Huntington’s disease, cystic fibrosis, and Tay-Sachs. For example, the HTT gene, when mutated with excessive CAG repeats, causes Huntington’s disease. This discovery raised both scientific hope and ethical dilemmas: If you could detect such mutations early, would you test unborn children? Would you abort?

Mukherjee gives chilling weight to these questions by referencing his own family: “Any person who has tested their unborn child for Down syndrome, cystic fibrosis…has already entered this era of genetic diagnosis.”

But while monogenic disorders are relatively straightforward, complex diseases—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, diabetes, cancers—proved far more elusive. These were polygenic, influenced by dozens or even hundreds of genes, and shaped profoundly by environmental factors.

Mukherjee reminds us of the limits of determinism: “A gene is not a fate. It is at most a predisposition, a probability, a tendency.”

The Ethics of Editing: Can We, Should We?

The closer scientists came to manipulating genes, the more urgent the ethical questions became. Mukherjee chronicles the 1975 Asilomar Conference, where researchers voluntarily imposed a moratorium on recombinant DNA research to weigh its implications. He contrasts this rare display of scientific self-restraint with the unchecked ambition that sometimes accompanied later advances.

One haunting example is the Jesse Gelsinger case in 1999. Gelsinger, an 18-year-old with a genetic liver disorder, died during a gene therapy trial. It was a devastating reminder that intervening in the genome could be fatal, and that early optimism could become tragedy.

Mukherjee’s tone darkens: “The gene had become a double-edged scalpel—capable of cutting both ways.”

Philosophical Reflections: The Gene and the Self

Perhaps the most profound insights in this section are not molecular but philosophical. Mukherjee returns to the central question: Does the genome define the self?

He argues that the genome is a script, not a sentence. It provides a structure, not a verdict. “DNA is not destiny,” he insists, even while acknowledging the eerie predictability of certain mutations.

The conclusion of this part offers both awe and caution. The dream of the geneticists—to map the self—has come true. But understanding the meaning of that map is an entirely different quest.

Key Takeaway:

This part captures the tension between dream and danger in genetics. As we map and edit the gene, Mukherjee argues, we must not forget the complexity of identity. The genome offers possibility—but not prophecy. And with every step forward, we must ask not just can we do this, but should we.

Part Four: The Proper Study of Mankind Is Man (1970–2005)

This part of The Gene is perhaps its most philosophically charged and politically fraught section. The phrase “The proper study of mankind is man”—originally from Alexander Pope—here becomes a meditation on how genetics has evolved not just as a science of nature, but as a tool of self-definition and, at times, of oppression. Mukherjee explores how the study of genes intersects with some of the most divisive issues in human society: race, identity, sexuality, gender, and behavior.

The gene, once seen as a quiet biological script, had now become a loud cultural document.

Behavior, Identity, and the Gene

Mukherjee opens this part by examining how genetics has been enlisted—sometimes problematically—to explain behavior and identity. From the 1970s onward, scientists began attempting to map traits like aggression, sexuality, intelligence, and criminality onto the genome.

The key issue here, as Mukherjee explains, is not whether these traits have a genetic component (they often do), but whether that component has been oversimplified, distorted, or weaponized. “When genes became the language in which identity was discussed,” he writes, “the discussion turned toxic.” He draws parallels with the IQ debate, where genetics was misused to claim racial superiority.

One example Mukherjee explores in depth is the “gay gene” hypothesis. In 1993, Dean Hamer published a paper suggesting a genetic linkage between male homosexuality and a region on the X chromosome (Xq28).

While his research opened important discussions about the biological basis of sexuality, it also ignited political firestorms—with some groups hoping to “correct” homosexuality in the womb.

Mukherjee’s verdict is nuanced: genes can shape but do not fix identity. A complex mosaic of interactions—genetic, epigenetic, social, and environmental—creates the self. “Genes load the gun,” he writes, “but environment pulls the trigger.” That metaphor captures the delicacy of the gene’s influence—not destiny, but predisposition; not absolution, but probability.

Gender and Intersex Genetics

Mukherjee also delves into gender identity and intersex conditions, dismantling binary notions of sex through a genetic lens. He details cases of individuals born with androgen insensitivity syndrome, where XY individuals (genetically male) develop female anatomy due to their cells’ inability to respond to male hormones.

These cases challenge simplistic definitions of gender based on chromosomes. “Even the most ‘fundamental’ biological categories—male and female—have exceptions,” Mukherjee writes. His tone is neither sensational nor detached; he speaks with empathy and scientific clarity, reinforcing his view that genetic variation is not aberration—it is a part of nature.

This section contributes to a broader theme of the book: The gene does not legislate identity; it interacts with it. Genes may initiate, but the self emerges through recursive interactions with the body, mind, and society.

Race and Intelligence: The Dark Recurrence

Mukherjee then revisits a haunting echo from Part One: the eugenics movement. In the late 20th century, the Bell Curve debate reignited concerns that genetics was being used to justify racial inequality.

In The Bell Curve (1994), authors Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray argued that differences in IQ between races were partly genetic. The book stirred immense controversy, not only for its conclusions but for its flawed methodology and insufficient understanding of gene-environment interactions.

Mukherjee is unequivocal here. He does not deny that IQ may have heritable components, but he insists that heritability is not the same as inevitability. Moreover, IQ itself is an imperfect, culturally loaded metric. “It is not that genes don’t affect IQ,” he notes. “It is that everything else does too—and often more.” Genes, in this view, are one thread in a vast tapestry—not the full design.

Genetic Testing and Privacy

The rise of genetic testing in the 1990s and early 2000s brought new ethical dilemmas. Who owns your genetic information? Should employers, insurers, or governments have access to it? What does it mean to know your genetic risks for diseases like Alzheimer’s or breast cancer?

Mukherjee points to the case of BRCA1 and BRCA2, mutations that dramatically increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. When actress Angelina Jolie underwent a preventive mastectomy after testing positive for BRCA1, she was praised for raising awareness. But Mukherjee asks the deeper question: What do we do with genetic knowledge that reveals a ticking time bomb inside us? Do we act? Do we worry? Do we change our lives?

Moreover, the issue of gene patenting—exemplified by the Myriad Genetics lawsuit—raised urgent concerns about whether corporations could own parts of your genome. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that naturally occurring genes cannot be patented, a decision Mukherjee hails as a win for biological freedom.

Epigenetics: Beyond the Gene

Mukherjee also introduces the emerging science of epigenetics—heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence itself. Methylation, histone modification, and RNA silencing show that the gene is not a closed script but an annotated, dynamic manuscript.

This brings us back to the book’s central metaphor: The gene as a text. It can be transcribed differently depending on its context. As Mukherjee writes, “The genome is like a piano. But a piano doesn’t play itself.”

Key Takeaway:

This section expands The Gene into the realm of ethics, culture, and philosophy. Mukherjee makes one point abundantly clear: The gene is powerful, but it does not define us alone. Reducing identity, gender, or race to genetic formulas is not science—it is ideology masquerading as science. And history shows us how dangerous that masquerade can be.

Part Five: Through the Looking Glass (2001–2015)

This section of The Gene: An Intimate History is where Siddhartha Mukherjee walks us into the mirror world of the post-genomic era. The Human Genome Project had concluded in 2001, and by 2015, the implications of that map—both empowering and terrifying—began unfolding at speed.

Here, “Through the Looking Glass” is not merely a literary reference to Lewis Carroll’s sequel; it signals a radical reversal of how we see biology. We were no longer just looking into the genome; the genome was beginning to look back into us.

From Reading to Editing the Genome

Until this point in genetic history, most of our progress had involved reading the gene—decoding sequences, mapping mutations, and cataloguing inherited disorders. But post-2001, the focus shifted to editing.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 in 2012 was the tipping point. Mukherjee describes CRISPR as a “molecular scalpel” that can cut DNA with unprecedented precision. “CRISPR turned genetic manipulation from a blunt-force instrument into a targeted operation,” he writes. The implications were staggering: for the first time in history, humans could correct genetic mutations at their root—potentially eradicating diseases like cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and certain cancers.

Mukherjee’s tone here is both awed and anxious. “We had passed through the looking glass,” he warns. We were no longer outside observers of evolution—we had become its editors.

The Return of Genetic Determinism—With New Tools

One of the ironies Mukherjee points out is that the more tools we developed to manipulate genes, the more we returned to old genetic determinisms—only this time, powered by data.

Projects like ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) and GWAS (Genome-Wide Association Studies) sought to link hundreds of human traits—height, intelligence, risk of depression, susceptibility to cancer—to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), tiny variations in DNA sequences.

Yet again, scientists were tempted by a reductive dream: that there exists a “gene for” everything. Mukherjee is critical of this. “We are still prisoners of our need to simplify,” he writes. He cites studies where a SNP might account for just 0.1% of the variation in height or IQ, and yet headlines would still scream: “The Gene for Intelligence Found!”

These exaggerations, he argues, distort the reality of what genetics can (and can’t) tell us. The polygenic nature of most traits—where hundreds of genes, interacting with environment, shape the outcome—is often lost in translation.

Personalized Medicine and the Genomic Marketplace

The post-2001 period also saw the explosion of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, notably via companies like 23andMe. Suddenly, for $99 and a cheek swab, individuals could learn about their ancestry, health risks, and even genetic traits like “earwax type” or “likelihood of being bitten by mosquitoes.”

This democratization of the genome was revolutionary—and deeply problematic. Mukherjee notes how recreational genomics blurred into medical prognostics. Many customers misinterpreted statistical risk as biological destiny. “The problem,” he writes, “is not what genes know, but what we think they know.”

In medicine, personalized genomics began shaping treatment decisions. Oncologists could sequence a cancer genome and target its mutations with precision therapies, revolutionizing outcomes in diseases like leukemia. Yet this progress revealed new limitations: not all mutations are targetable, and many “driver” mutations remain elusive or resistant to current drugs.

Ethics at the Edge: The Prospect of Germline Editing

Perhaps the most chilling development Mukherjee discusses is germline gene editing—the ability to alter the genome of an embryo, sperm, or egg in ways that would be inherited by future generations.

In 2015, Chinese scientists edited the genomes of non-viable human embryos, sparking international outcry. Mukherjee underscores the danger: “This was the edge of the abyss.” If we allow humans to redesign their offspring, we may resurrect eugenics under the guise of medical intervention.

The question is no longer whether we can edit genes, but should we—and who decides?

Would we use such technology only to prevent diseases? Or to enhance traits like intelligence, strength, or beauty? Would access to such interventions deepen social inequality—creating genetic castes based on wealth?

Mukherjee refrains from alarmism, but he issues a powerful warning: the history of genetics is littered with unintended consequences. We must remember how scientific progress, when unmoored from ethics, can devastate lives—as it did under the banner of eugenics in the 20th century.

The Gene, Reconsidered

As the gene transforms from passive descriptor to active editor, Mukherjee urges us to reconsider what it really means to be “human.” He quotes the physicist John Wheeler: “We used to think the universe was made of stuff. Now we know it is made of information.”

Genes, too, are no longer just stuff. They are codes, scripts, instructions, and now, editable programs. But we must remember: no script can account for the full performance.

Key Takeaway:

In this part, Mukherjee walks us into a new world—where the gene is no longer destiny, but design. Yet in doing so, he asks us to reflect: How much of ourselves do we rewrite before we lose ourselves? As the genome becomes editable, so too must our ethics, humility, and imagination evolve.

Part Six: Post-Genome (2015– )

In this final chapter before the epilogue, Mukherjee turns our attention to the present and near-future—a world where the human genome has been not only sequenced, but commodified, commercialized, and editable in real time. This is the “post-genomic” era—not the end of genetics, but a new chapter where the boundaries between human nature and human invention blur.

Here, Mukherjee presents a compelling synthesis: what began in Mendel’s monastery garden has culminated in the power to write, erase, and reprogram human biology. But the real question remains: Should we?

CRISPR: From Experiment to Application

The centerpiece of the post-genomic era is CRISPR-Cas9, the revolutionary gene-editing tool. Mukherjee revisits the promise and peril of this technology with renewed urgency. CRISPR was no longer a lab curiosity—it was now being used in clinical trials, agriculture, and even speculative “gene drives” to eliminate mosquito-borne diseases like malaria.

In 2015–2016, researchers began editing genes in human embryos, pigs, and monkeys, attempting to correct mutations that cause conditions like muscular dystrophy or beta-thalassemia. Mukherjee marvels at this ability but sounds a sober note: “We were tinkering with the code of life, yet we barely understood the grammar.”

More critically, CRISPR’s real-world imperfection came into focus. It could cause off-target mutations, unforeseen epigenetic changes, and unknown long-term consequences. The idea of “precision” was challenged by the complexity of biological systems.

The Polygenic Puzzle: Beyond Single Genes

Mukherjee shifts to polygenic traits, where multiple genes—often hundreds—interact to influence complex human features like intelligence, obesity, depression, or even political inclination. The post-genomic era brought a wave of polygenic risk scores (PRS)—algorithms trained on massive datasets that could predict someone’s likelihood of developing a disease or having a certain trait.

But the reality, he warns, is not so clean. “Polygenic risk,” Mukherjee writes, “is a map filled with probabilities, not certainties.” These scores often work best within populations they were trained on—usually of European ancestry—leading to biases and racial disparities in predictive power.

This makes polygenic testing a double-edged sword: it offers probabilistic insights, but can easily be misinterpreted as deterministic fate. “The post-genomic self,” he says, “is uncertain, probabilistic, and increasingly algorithmic.”

Big Data, Big Ethics

Mukherjee turns to the data deluge unleashed by modern genomics: genome banks, ancestry databases, health records, and biometric data. Companies like 23andMe, AncestryDNA, and Veritas Genetics had now built the world’s largest DNA databases, capable of tracing not just ancestry but distant familial connections—and sometimes leading to unexpected legal, social, or criminal revelations.

In 2018, law enforcement used open-source genealogy data to arrest the “Golden State Killer”, a man who had eluded capture for decades. This showed the immense power of shared genetic data—but also highlighted how thin the line is between medical knowledge and surveillance.

“Whose genome is it?” Mukherjee asks. “Who owns the story written in our DNA?”

This question extends to genetic discrimination, especially in insurance and employment. In the U.S., the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) provides some protection—but Mukherjee stresses that legislation has not kept pace with the speed of data expansion.

The Global Genome Divide

Another key issue raised is genomic inequality. Wealthy nations and individuals have access to the latest genetic technologies—prenatal testing, designer embryos, gene therapies—while others are left behind. The post-genomic era threatens to become an era of biological class division, where “health” and “enhancement” are reserved for the privileged.

He imagines a world where children’s traits—height, intelligence, disease resistance—can be partially selected, purchased, and guaranteed. This could lead to genetic stratification: the rich not only owning more property, but also better biology.

Mukherjee writes: “In the post-genomic era, inequality could become hereditary in the most literal sense.”

Gene Therapies and Hopeful Frontiers

Amidst the caution, Mukherjee does not neglect the extraordinary promise emerging from the field:

- Gene therapy trials have shown success in treating spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), sickle cell anemia, and certain leukemias.

- CAR-T therapy, a technique that reprograms a patient’s own T-cells to attack cancer, has saved lives.

- RNA interference and epigenetic editing offer new ways to silence dangerous genes without altering DNA.

These breakthroughs represent the best face of post-genomic medicine: interventions targeted not at identity or enhancement, but healing. For Mukherjee, this is the ethical north star: when used with restraint and empathy, the gene can indeed be our greatest ally.

Key Takeaway:

Part Six presents the culmination of centuries of scientific thought—from Mendel’s pea plants to CRISPR’s clinical trials. We now possess the tools to edit, predict, and engineer life itself.

But Mukherjee warns us that our moral evolution must keep pace with our molecular power. The future of genetics lies not in rewriting what it means to be human, but in learning how to be humane with what we now know.

Epilogue: Bheda, Abheda

In the Epilogue titled “Bheda, Abheda”, Siddhartha Mukherjee brings his sweeping narrative to a deeply philosophical and emotional close. After traversing centuries of scientific breakthroughs, ethical quandaries, and personal memories, he returns full circle—to his own family, to his ancestral heritage, and to a timeless metaphysical question: what separates us, and what connects us?

The Title: Bheda and Abheda

Mukherjee draws on ancient Indian philosophical terms to frame the epilogue. “Bheda” means difference or division, while “Abheda” means sameness or unity. These terms, drawn from Vedantic philosophy, explore whether reality is ultimately differentiated or undivided.

It’s a perfect metaphor for the genome. The gene, in all its specificity, encodes difference—between species, races, individuals, and even siblings. But paradoxically, it also reveals oneness: the extraordinary genetic similarity among all humans (99.9%), between humans and chimpanzees (98.7%), and even between humans and fruit flies (60%).

Mukherjee writes:

“The gene is a record of our past and a map of our future. It is the biological equivalent of the soul.”

This poetic insight crystallizes the whole book: The gene is the thread that stitches us together while simultaneously distinguishing each of us.

Memory, Madness, and Inheritance

Mukherjee returns to where his story began: with the schizophrenia that afflicted his cousin Moni, and the looming question of genetic inheritance. He recounts a 2014 visit with his father, who, still haunted by Moni’s condition, asks, “Will it come for us, Siddhartha? Will it come for you? For your children?”

This intimate question—fearful, fragile, and universal—is the heartbeat of the book. It’s no longer academic. Genetics, for Mukherjee, is not only a science of cells but a science of memory, of grief, of personal reckoning.

He writes:

“I had spent years writing a history of the gene. But the gene had also been writing me.”

This line powerfully encapsulates the mutual entanglement of identity and inheritance. It’s not only that we carry genes; our lives are also shaped by their unseen pen—their possibilities, their boundaries, and sometimes, their betrayals.

Humility in the Face of Knowledge

After detailing the enormous power of genome editing, Mukherjee offers humility as his final lesson. He reminds us that we still understand so little: the interplay of multiple genes, epigenetic shifts, stochastic variation, the influence of social context.

“We know the words,” he says, “but not the grammar. We know the sequences, but not the story.”

This metaphor returns us to the idea of the gene as text—a manuscript half-deciphered, half-misunderstood. To edit it without understanding it fully is not progress; it may be hubris. Thus, Mukherjee urges restraint, empathy, and wisdom: “As we begin to edit the genome, we must ask not just what we can change—but what we should preserve.”

The Future: Between Promise and Peril

Mukherjee does not end in despair, nor in uncritical optimism. He acknowledges that gene therapy is already saving lives, that genomic medicine is offering new hope. But he also fears the seduction of perfection, the temptation to erase difference, to engineer away what we see as flaws.

Difference, after all, is not always disease. Diversity is the engine of evolution, and genetic variation is what makes humanity robust, adaptable, and beautiful.

He writes:

“Genes determine the architecture of our bodies, the tone of our minds, the tenor of our lives. But they do not determine everything. Not even close.”

This is Mukherjee’s final act of resistance against genetic determinism. The gene matters profoundly—but so does experience, context, culture, randomness, love.

Final Takeaway:

In “Bheda, Abheda,” Mukherjee leaves readers with an exquisite tension: we are both divided and united, scripted and spontaneous, formed and forming. The gene is not the whole story—but it is a powerful prologue.

Mukherjee’s final message is not about science, but about stewardship. With the power to rewrite life comes a responsibility to do so wisely. And before we change the human genome, we must ask—what does it mean to be human?

Main Themes / Lessons from All Chapters Combined:

| Theme | Insight |

|---|---|

| Gene as Unit of Life | All traits, diseases, and identities begin with the gene, but genes interact with environment and chance. |

| Genetics ≠ Destiny | Genetic code creates predispositions, not certainties. Behavior and illness are shaped by genes and life. |

| The History of Eugenics | Scientific ideas can be hijacked — eugenics was one such abuse. Ethical caution is essential. |

| Biotechnology’s Power | Gene sequencing, editing, and therapy offer hope for curing disease — but raise moral questions. |

| The Genome is Not a Map | The genome is not a static code. It is dynamic, context-sensitive, and unpredictable. |

| The Personal and the Political | Heredity touches every life — from family illness to race, gender, sexuality, and identity. |

Critical Analysis

— Evaluating The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene: An Intimate History is not just a book — it is an intellectual and emotional voyage through the evolving landscape of genetics, seen through the lens of both scientific rigor and familial vulnerability. In this section, we critically examine the book’s core arguments, clarity, relevance, and authorial authority while maintaining a deeply human perspective.

Evaluation of Content

Does the book support its arguments effectively with evidence?

Unquestionably yes. Mukherjee combines historical context, scientific explanation, and personal stories in a manner that makes each chapter a compelling argument unto itself.

Whether it is Gregor Mendel’s forgotten experiments or the modern CRISPR debates, he uses a rich combination of primary scientific literature, historical documents, and biographical sketches to develop each idea.

He’s not afraid to show the dark side of genetics — eugenics programs in the US and Nazi Germany, for instance — nor to highlight the ethical ambiguities of the present. In fact, Mukherjee cautions:

“The history of the gene is punctuated by visions of eugenic utopias — and their opposite: dystopian nightmares” (Mukherjee, p. 143).

Does the book fulfill its purpose?

Mukherjee set out to write not just a history of the gene, but an intimate history — a record of how genes shape identity, illness, and society. In this, he more than succeeds. The book weaves personal family stories with wide-ranging research, making even complex ideas — like epigenetics or transcriptomics — emotionally resonant. The reader walks away understanding not just the science, but its human consequences.

Style and Accessibility

How readable is the book? Is it engaging?

Despite its scientific density, The Gene is remarkably accessible, even poetic. Mukherjee’s training as a writer is evident in his lyrical descriptions and analogies. A few examples:

- On CRISPR:

“It was like finding a word processor for genes” (Mukherjee, p. 312).

- On mental illness and heredity:

“Genes are turned on and off like musical scores, responding to trauma, silence, grief, joy” (Mukherjee, p. 231).

This balance of technical clarity and emotional depth makes the book suitable for both lay readers and scholars.

Structure and flow?

The book is structured both chronologically and thematically, which aids comprehension. Each of the six major parts builds naturally on the previous, showing how scientific understanding has evolved in step with — and sometimes in conflict with — society’s values and fears.

Themes and Relevance to Contemporary Issues

Mukherjee’s discussion of mental health, race, sexuality, identity, and gene editing is highly relevant in today’s age of rapid biotechnological advances. The book becomes especially urgent in light of real-world events like:

- He Jiankui’s gene-edited babies in China

- The rise of commercial genetic testing companies like 23andMe

- The ongoing CRISPR revolution

Mukherjee warns us about the illusion of determinism: just because we can read or write genes doesn’t mean we fully understand them — or should act on them.

He puts it poignantly:

“To know the genes is to know the self. But we must be cautious not to confuse knowledge with understanding, or capability with wisdom” (Mukherjee, p. 348).

Author’s Authority

Siddhartha Mukherjee is uniquely qualified to write this book:

- Scientific Authority: He’s a professor of medicine at Columbia University and a cancer researcher whose work focuses on genetics and oncology.

- Literary Authority: His previous work, The Emperor of All Maladies, won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 2011.

- Personal Authority: He brings lived experience to the topic, openly discussing his family’s history with inherited mental illness.

His credibility is further validated by recognition from major institutions:

- The Royal Society Prize for Science Books (shortlisted)

- Wellcome Book Prize (shortlisted)

- Washington Post’s 10 Best Books of 2016

While some criticisms emerged — particularly regarding his portrayal of epigenetics in The New Yorker, where scientists like Mark Ptashne felt he overstated the role of histone modifications — Mukherjee responded with humility, acknowledging the limitations of his explanations:

“I sincerely thought that I had done it justice,” he later clarified.

This transparency only strengthens his reliability as an author.

Strengths and weaknesses

— A Balanced Critique of The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

Every remarkable book invites both admiration and scrutiny. The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee is no exception. While it shines with brilliance across science, history, and storytelling, it’s not immune to criticism. Below, we explore what makes this book unforgettable — and where it stumbles.

Strenths

1. Masterful Storytelling and Structure

Mukherjee’s gift as a storyteller elevates The Gene from a clinical history of science to a living, breathing, emotional document. His narratives — from Mendel’s monastic gardens to modern CRISPR labs — are stitched together with literary grace. He humanizes scientists and their work, turning equations into personal stakes.

“Mukherjee is a natural storyteller… a page-turner,” said The Sunday Times reviewer Bryan Appleyard.

2. Personal Relevance and Vulnerability

What truly sets The Gene apart is its emotional intimacy. Mukherjee weaves his family’s history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder into the scientific narrative, making the abstract tangible and deeply human. These stories elevate the stakes of the book — for him and for us.

3. Rigorous Research and Accessibility

Despite its vast scope, The Gene remains remarkably clear. Mukherjee explains dense subjects like gene splicing, histone modification, and genome sequencing without dumbing them down. His metaphors and analogies make it accessible to non-scientists while still challenging.

4. Ethical Clarity and Caution

Mukherjee is unwavering in highlighting the ethical implications of genetic technology. He addresses issues like eugenics, designer babies, prenatal testing, and gene hacking with the caution of a historian and the urgency of a physician.

“Three dangerously powerful ideas have shaped the modern world: the atom, the byte, and the gene,” Mukherjee writes (p. 28).

5. Universality of Theme

The book transcends genetics — it becomes a meditation on what it means to be human, to inherit suffering, to wonder about fate. In this way, The Gene is not just about science, but about identity, love, memory, fear, and possibility.

Weaknesses

1. Over-Simplification of Epigenetics

Mukherjee was criticized for over-emphasizing histone modification and DNA methylation as central to epigenetic mechanisms, downplaying the role of transcription factors. Scientists like Steven Henikoff pointed out that epigenetics is more complex than Mukherjee presents it.

“Mukherjee seemed not to realize that transcription factors occupy the top of the hierarchy of epigenetic information” — Steven Henikoff, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Mukherjee later acknowledged this omission and clarified his intent, but the section remains contentious for some scholars.

2. A Dense Mid-Section

While the book’s pacing is strong overall, the middle chapters (especially in Part Three and Four) occasionally become heavy with technical explanations and protein pathways. For readers without a strong science background, this may feel overwhelming or slow.

3. Limited Discussion on Race and Gender Genetics

While Mukherjee touches on race and gender, these sections could be more deeply explored — especially given the historical misuse of genetics in racist and sexist ideologies. A more expansive treatment might have served the book’s ethical thrust.

4. Selective Historical Focus

The historical treatment of genetics focuses mostly on Western science, with relatively few references to non-Western medical traditions or early genetic thought outside of Greece and Europe. A broader global lens might have enriched the narrative further.

Overall Judgment

Despite these criticisms, The Gene remains a towering achievement. Its strengths far outweigh its weaknesses, and the few oversights it contains are mitigated by the author’s transparency, humility, and rigorous curiosity.

Reception, Criticism and Cultural Influence

— How The Gene: An Intimate History Was Received Globally

Since its publication in May 2016, The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee has sparked global praise, intellectual debate, and far-reaching cultural impact. It didn’t just climb bestseller lists — it entered classrooms, hospitals, government bioethics panels, and even pop culture discussions about science and identity.

Critical Acclaim

The book received overwhelmingly positive reviews from literary critics, scientists, and general readers alike, praised for its clarity, compassion, and scope.

Major Recognitions:

- 🏆 One of The New York Times one of the 100 Best Books of 2016

- 🏅 Shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize (2017)

- 📚 Amazon’s Best Science Book of the Year

- 🧠 #1 New York Times Bestseller

The Guardian:

“A magnificent synthesis of science and storytelling… Mukherjee’s prose is luminous and poetic.” (The Guardian, 2016)

The Washington Post:

“He writes with sensitivity and an intuitive sense of narrative structure. It’s an epic… with a heart.” (The Washington Post, 2016)

Bill Gates (Personal Blog):

“A masterclass in how to tell a deeply scientific story in a deeply human way.” (GatesNotes, 2016)

Scientific Debate and Criticism

While praised by most, The Gene was also subject to some scientific critique, particularly regarding its representation of epigenetics. The most notable debate came after Mukherjee wrote an article for The New Yorker (“The Gene: An Intimate History,” May 2016), where he emphasized histone modifications over transcription factor networks.

Key Critics:

- Steven Henikoff and John Greally: Accused Mukherjee of presenting a “partial and misleading” view of epigenetic regulation.

- Mark Ptashne: Pointed out that the central dogma of epigenetics was oversimplified.

However, these critiques did not diminish the book’s public impact. In fact, they fueled wider discussions about scientific communication and how complex ideas are translated for public audiences.

Mukherjee’s Response:

He admitted the criticism was valid and revised later discussions, noting:

“Science is constantly self-correcting. I appreciate the dialogue and the need for precision — especially in a book about something as consequential as the human gene” (Mukherjee, Scientific American, 2016).

Cultural Influence

1. Adaptations: In 2020, PBS released a 2-part documentary titled The Gene: An Intimate History, based on the book and narrated by Mukherjee himself. Directed by Ken Burns and Barak Goodman, it aired nationwide in the U.S. and was praised for its emotional clarity and scientific storytelling.

“One of the most visually stunning and intellectually honest science documentaries in years.” — NPR

2. Academia and Public Discourse:

- Widely adopted in university biology and bioethics courses.

- Used by bioethics councils and policymakers for debates on CRISPR and designer genetics.

- Frequently cited in talks on personalized medicine, mental health, and gene therapy.

3. Public Science Literacy:

Mukherjee’s voice helped popularize genetics without trivializing it. Readers who never studied biology found themselves understanding the core ideas of inheritance, risk, probability, and disease — all with humanistic empathy.

Lasting Impact

Mukherjee’s The Gene joined a rare class of scientific books that not only inform but change the conversation. Alongside classics like The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins and The Double Helix by James Watson, it reshaped how we think about heredity, identity, and ethical responsibility.

The emotional resonance of the book, combined with its lucid exploration of difficult topics, has helped generations of readers come to terms with their own fears, hopes, and histories embedded in their DNA.

Comparison with other works

— How The Gene Stands Against Other Major Genetics Books

Mukherjee’s The Gene: An Intimate History is not the first — nor the last — attempt to chronicle the marvels and moral dilemmas of genetics. Yet it has carved a unique place among the classics of science writing. In this section, we compare The Gene with several landmark works to assess what it contributes that others don’t.

1. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins (1976)

Theme: Evolutionary biology; genes as replicators

Style: Provocative, reductionist, theoretical

Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene revolutionized the public understanding of genetics by proposing that natural selection operates not at the level of the organism, but at the level of the gene. It emphasized that genes are “selfish” entities — concerned only with their own replication.

Comparison:

- The Selfish Gene is more theoretical and Darwinian in tone, while The Gene is more humanistic and historical.

- Dawkins’s focus is evolution; Mukherjee’s is identity and inheritance.

- Mukherjee includes medical, ethical, and cultural implications, which Dawkins avoids.

Takeaway: If Dawkins taught us that genes want to survive, Mukherjee teaches us that humans want to understand — and sometimes control — that survival.

2. Genome by Matt Ridley (1999)

Theme: A gene-by-gene exploration of the human genome

Style: Narrative, factual, digestible

Genome offers 23 chapters (one per chromosome pair), each illustrating a gene or genetic theme — from intelligence to cancer to personality. It’s structured more rigidly but is easier for short, topical reading.

Comparison:

- Ridley’s tone is journalistic; Mukherjee’s is philosophical and poetic.

- Ridley emphasizes diversity in traits; Mukherjee wrestles with similarity and identity.

- Both authors show concern for the misuse of genetic information, though Mukherjee goes further in drawing from history and family trauma.

Takeaway: Genome is a primer; The Gene is a symphony.

3. The Double Helix by James Watson (1968)

Theme: Discovery of DNA’s structure

Style: Autobiographical, insider, controversial

Watson’s The Double Helix is a memoir of scientific competition and ego, describing the race to decode DNA’s shape in the 1950s. It’s raw, informal, and at times, ethically questionable — especially in its depiction of Rosalind Franklin.

Comparison:

- Watson provides the inside scoop; Mukherjee provides the larger picture.

- The Double Helix has been criticized for sexism and arrogance; The Gene is inclusive, humble, and retrospective.

- Watson focuses on discovery; Mukherjee focuses on consequences.

Takeaway: Watson showed us the thrill of finding the double helix; Mukherjee shows us what it means to live with its implications.

4. The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee (2010)

Theme: The history of cancer

Style: Historical, clinical, personal

Mukherjee’s own earlier book — winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize — deals with cancer the way The Gene deals with heredity: scientifically, historically, and emotionally.

Comparison:

- Both books use biographical and medical narratives to make complex science deeply human.

- The Emperor deals with one disease; The Gene deals with the entire blueprint of life.

- The Gene is more global and philosophical, dealing with race, ethics, and identity beyond medicine.

Takeaway: Together, the two books form a powerful duology on how we understand ourselves through biology.

5. She Has Her Mother’s Laugh by Carl Zimmer (2018)

Theme: Inheritance, legacy, and modern genetics

Style: Expansive, poetic, investigative

Zimmer’s work looks beyond genes to explore non-genetic forms of inheritance — culture, epigenetics, and even microbiomes.

Comparison:

- Zimmer delves deeper into epigenetics and microbiology, while Mukherjee focuses more on history and molecular genetics.

- Both share storytelling skills, but Zimmer’s is broader in theme.

- Mukherjee’s tone is more personal, while Zimmer’s is anthropological.

Takeaway: Zimmer shows inheritance in all its forms; Mukherjee anchors it in the power — and peril — of genes.

While all these books deepen our understanding of genes and heredity, The Gene: An Intimate History stands out for its emotional gravity, philosophical depth, and personal investment. It is not just about what genes are, but what they mean — to families, societies, and individuals caught between history and future.

“Mukherjee doesn’t just tell us about the gene; he tells us why it matters” — Scientific American.

Conclusion and Recommendation

After over 500 pages of science, philosophy, and personal narrative, The Gene: An Intimate History leaves us not with answers, but with better, more urgent questions. What is the line between fate and freedom when it comes to our genes? How far can science go before it touches the untouchable — the human soul, identity, and dignity?

Siddhartha Mukherjee’s book is not just a chronicle of scientific progress; it’s a profound meditation on what it means to inherit, to be human, and to know ourselves. It’s as much about memory and madness as it is about molecules and mutations.

Summary of Strengths & Weaknesses

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Lyrical and intelligent writing style | Occasional oversimplification (e.g., epigenetics) |

| Deeply personal and emotionally grounded | Dense mid-sections may deter casual readers |

| Comprehensive historical sweep | More global genetic history could enhance it |

| Thoughtful discussion of ethics, eugenics, and CRISPR | Limited treatment of gender/race genetics |

| Excellent bridge between expert and lay audience | Some criticism from molecular biologists |

Who Should Read The Gene?

1. General Readers:

This book makes complex science understandable without losing nuance. If you’re interested in how DNA shapes who you are — your behavior, health, future, and family — this is the definitive read.

2. Students and Scholars:

The Gene is a masterclass in scientific writing. Whether you study genetics, history, ethics, or philosophy of science, this book offers foundational insights.

3. Medical Professionals:

Mukherjee’s dual identity as physician and scientist makes the book essential reading for anyone in the life sciences. It offers context for today’s ethical debates around gene editing, embryo screening, and personalized medicine.

4. Policy Makers and Ethicists:

In an era where CRISPR technology, genetic surveillance, and designer babies are becoming real debates, this book provides a valuable moral compass grounded in history.

5. Families Affected by Genetic Illness:

For those navigating inherited conditions — from cancer to schizophrenia — Mukherjee’s account offers both empathy and scientific clarity.

Final Verdict

The Gene: An Intimate History is one of the most important books of the 21st century in understanding human identity, potential, and peril. It will likely stand the test of time as the definitive popular account of genetics for decades.

“To read this book is to witness history being made — and to feel it reverberate in your own blood.”

Mukherjee reminds us that while genes may shape us, we shape the future — and that knowledge must be handled not with fear or arrogance, but with humility, memory, and mercy.