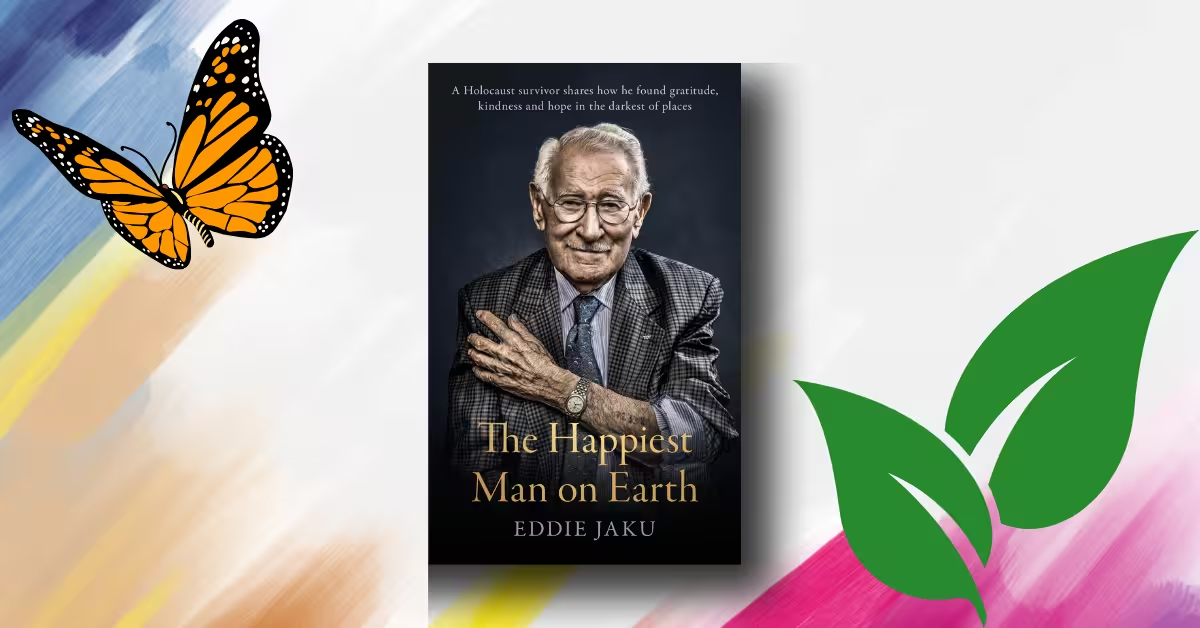

We say we want happiness, but most of us spend our days rushing, scrolling, and stewing. Eddie Jaku—who survived Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and a death march—argues in his The Happiest Man on Earth that the antidote is simple, difficult, and urgent: choose to live with kindness, gratitude, and purpose, even when the world collapses.

Happiness is a disciplined choice—nurtured by friendship, love, decency, and small daily acts—because, as Eddie reminds us, “life can be beautiful if you make it beautiful” (and yes, he insists you can) .

The 7-minute “Double Happiness” ritual.

- Text or tell one person, “Something you did recently mattered to me because ___.”

- Write one line in a pocket note: “Today I’m lucky because ___.”

- Do one tiny kindness you won’t tell anyone about.

(Eddie’s rule of thumb: without friendship and gratitude, the soul starves; “One good friend can be your entire world.”) .

Evidence snapshot

- Gratitude boosts well-being. Randomized trials show people who kept gratitude lists reported better mood and health versus controls (Emmons & McCullough).

- Relationships extend life. Meta-analysis of 148 studies (308,000+ participants) found strong social ties are linked to a 50% higher survival rate, an effect on par with major health risks.

- Growth after trauma is real (and complex). The post-traumatic growth literature documents positive changes in meaning, strength, and relationships following major adversity.

- Historical grounding. Author is a verified Auschwitz and Buchenwald survivor; institutional sources document camp facts and victim numbers.

Best for: Readers who want a short, humane blueprint for living better; students and families discussing the Holocaust; anyone in grief or rebuilding after a hard season; leaders looking to anchor a team culture in respect and responsibility.

Not for: Readers seeking a dense academic history; folks allergic to plain talk, aphorisms, or memoir-driven advice.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

This in-depth The Happiest Man on Earth summary distills Eddie Jaku’s most practical lessons, curated quotes, historical context, and research-backed tools—so you don’t have to flip back to the book. It blends Auschwitz survivor wisdom, resilience and post-traumatic growth, gratitude practice, and anti-hate education into a single, practical, searchable guide.

A compact Holocaust memoir and ethical handbook. Jaku survived Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and a death march; after liberation he built a family in Australia and volunteered for decades at the Sydney Jewish Museum, telling his story to fight hate and indifference. ;

Jaku states it without hedging: “I now consider myself the happiest man on Earth… life can be beautiful if you make it beautiful… happiness is something we can choose. It is up to you.”

2. Background

Eddie grew up in Leipzig in a patriotic, hardworking family (“Germans first… then Jewish”). After the Nazis rose to power, he was expelled from school for being Jewish; under a forged identity he trained as a precision engineer—skills that later helped him survive. ;

On Kristallnacht (9 Nov 1938), he was beaten, his family home destroyed, and he was sent to Buchenwald. The memoir recalls camp sadism and absurdities—like “games” where prisoners were released and immediately shot in the back—yet also the lifesaving intervention of an acquaintance who vouched for his toolmaking skills.

Later he endured Auschwitz, where “the average survival time… was seven months,” and the only thing that kept him from “going to the wire” (suicide by electrified fence) was friendship—especially with Kurt.

After liberation, Eddie rebuilt in Belgium and then Australia; he married Flore, had children, and chose a life devoted to kindness, education, and hope.

3. Summary

The Happiest Man on Earth is thematic, not strictly chronological. Every short chapter states a principle in plain language, then puts flesh on it with a scene you will not forget. Below, I integrate the lessons, signature lines, and the lived moments behind them, so you can carry the book’s spine in your head.

3.1 “There are many things more precious than money.”

In Leipzig, Eddie’s father—a Remington-trained master mechanic—modeled generosity and dignity: extra challah loaves were baked to share with the needy; guests were always welcome; character outweighed wealth. That early lesson would become Eddie’s compass when everything else was stripped away.

3.2 “Weakness can be turned into hatred.”

He watches neighbors he once trusted become looters and tormentors. The shock is not merely political; it is moral disorientation. The chapter squares with what we now know about how fear and humiliation are weaponized to justify cruelty—an urgent reminder in any polarized era.

3.3 “Tomorrow will come if you survive today. One step at a time.”

Eddie’s survival algorithm is stark: survive the next minute, then the next, because tomorrow exists only if you make it there. It’s not positive thinking; it’s micro-persistence under conditions designed to erase hope. (Chapter title, contents)

3.4 “You can find kindness everywhere, even from strangers.”

On the run through France, poor villagers share breakfast, bread, and shelter at personal risk. Gestures the size of a crust of bread become sacraments—a practical theology of everyday courage.

3.5 “Hug your mother.”

After arrests and escapes, family reunions are brief and perilous. The imperative is literal and ethical: hold the living close. (Chapter title)

3.6 “One good friend is my whole world.”

Auschwitz is “a living nightmare,” but Eddie and Kurt form a compact: share food, protect each other, keep each other from the fence. The Happiest Man on Earth’s most insistent claim comes here: “The greatest thing you will ever do is be loved by another person.” ;

This dovetails with strong epidemiology: relationships predict survival across age and health statuses.

3.7 “Education is a lifesaver.”

His engineering skill (toolmaking, optics) repeatedly keeps him alive. In a world of shortages, competence is currency. (Chapter head)

3.8 “If you lose your morals, you lose yourself.”

He observes how the SS prized obedience over conscience. It’s a warning: efficiency without ethics becomes a machine that eats people.

3.9 “The human body is the best machine ever made.”

Under starvation and cold, the body still repairs, endures, adapts. That reverence for embodiment grounds Eddie’s later counsel: sleep, eat simply, walk, and don’t poison your days with hatred.

3.10 “Where there is life, there is hope.”

Even on the death march, Eddie nurses tiny embers of hope—risking escape, literally under trains and over borders. After the war, hope becomes visible in a tandem bicycle with two small motors he rigs to ride with Flore—an engineer’s love letter to ordinary joy.

3.11 “There are always miracles in the world, even when it seems dark.”

Call them coincidences if you like; for Eddie, a smuggled tool or a stranger’s hand becomes grace with dirty fingernails.

3.12 “Love is the best medicine.”

Marriage and fatherhood transfigure survival into life: “Love saved me. My family saved me.”

3.13 “We are all part of a larger society…”

Happiness is social: work as contribution; memory as duty; decency as infrastructure. (Chapter head)

3.14 “Shared sorrow is half sorrow; shared pleasure is double pleasure.”

This is The Happiest Man on Earth’s community equation—the more you share, the more bearable life becomes. (Chapter head)

3.15 “What I share is not my pain… What I share is my hope.”

He refuses to center hatred; his revenge is tea and a biscuit with the woman he loves: “**We are still here; Hitler is down there… the only revenge I am interested in—**to be the happiest man on Earth.”

Threaded through the narrative

- Historical ballast. The Happiest Man on Earth presumes (and external sources confirm) the scale of the Holocaust: ~1.1 million murdered at Auschwitz, most of them Jews; six million Jews overall.

- Aphorisms with teeth. Lines like “Happiness does not fall from the sky; it is in your hands” are not greeting-card fluff; they were forged under electrified wire.

4. Critical Analysis

Does the content hold up?

As a witness memoir, its primary evidence is Eddie’s lived experience, bolstered by checkable history (Buchenwald, Auschwitz, death marches) and public records (volunteering at the Sydney Jewish Museum; awards; obituaries).

When The Happiest Man on Earth makes empirical-sounding claims, they’re measured: e.g., Eddie writes the “average survival time in Auschwitz was seven months,” a line that fits with the camp’s deliberate starvation and “extermination”.

Style & accessibility

The prose is clean, conversational, unpretentious—short chapters titled as rules you can remember. He writes to you as “my friend,” and the moral logic lands because it never lectures; it shows, then he names the lesson. (See the prologue’s direct address.)

Themes & contemporary relevance

- Dignity over despair: Survival is framed not as heroism but micro-choices: share a potato, hide a bar of soap for a friend (and therefore both of you live).

- Friendship and meaning: The social-ties literature now robustly supports Eddie’s insistence that companionship is medicine.

- Gratitude as practice: What might sound naive reads as discipline (see “Counting Blessings vs. Burdens”).

- Civic warning: The slide from humiliation to hatred and from rules to ritualized cruelty will always be relevant.

Author’s authority

A century of life, seven years in camps, decades of public testimony and education; recognized by the ABIA (Biography Book of the Year, 2021) and honored for service in Australia.

5. Strengths & Weaknesses

Strengths

- Memorable, portable lessons. Chapter titles double as mantras you can teach to a 10-year-old and still believe at 70.

- Emotion without sentimentality. The horrors are plain but presented to humanize, not to shock.

- Actionable ethics. You can implement his blueprint in seven minutes a day.

Weaknesses (or limits to note)

- Aphorism density. If you prefer footnoted argument over lived principle, the tone may feel too simple.

- Survivor’s lens. It’s one man’s story; use it to open discussion, not to homogenize all survivor experiences.

- Quantification. When Eddie mentions “average survival time,” treat it as contextual, not as a statistic you’d use in a methods class. (For historical numbers, lean on institutions like USHMM and Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial.)

6. Reception, Criticism, Influence

- Awards & sales: Won ABIA Biography Book of the Year (2021); described as a bestseller on publication.

- Public response: Obituaries and tributes consistently call him a “beacon of hope” who taught tolerance and kindness.

- Talks: Eddie’s TED Talk (“A Holocaust survivor’s blueprint for happiness”) crystallizes the book’s rules into a thirteen-minute testimony often used in classrooms.

- Stage adaptation: The memoir was adapted for the stage in 2023–2024.

7. Quotations

- “I now consider myself the happiest man on Earth.”

- “Life can be beautiful if you make it beautiful.”

- “Happiness does not fall from the sky; it is in your hands.”

- “The greatest thing you will ever do is be loved by another person.”

- “One good friend can be your entire world.”

- “Where there is life, there is hope.” (chapter head)

- “Love is the best medicine.” (chapter head)

- “Shared sorrow is half sorrow; shared pleasure is double pleasure.” (chapter head)

- “There are many things more precious than money.” (chapter head)

- “What I share is… my hope.” (chapter head)

8. Comparison with Similar Works

- Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning. Philosophical psychology from an Austrian psychiatrist who survived camps; stresses meaning as the human driver. Jaku’s focus is kindness, friendship, and choice in everyday acts.

- Elie Wiesel, Night. A spare, devastating account of faith and loss; Jaku offers a more explicitly hope-forward manual.

- Primo Levi, If This Is a Man. Analytic moral clarity, attention to systemic dehumanization; Jaku leans into micro-decencies and practical optimism.

- Edith Eger, The Choice. A clinical psychologist’s memoir about choosing freedom after trauma; close cousin to Jaku’s “happiness is in your hands” ethic.

9. Conclusion & Recommendation

Overall impression. This memoir is short in pages, long in aftertaste. It isn’t written to impress professors; it’s written to change your Tuesday. Eddie’s wisdom is less “self-help” than “self-and-others help.” It asks you to practice what you say you believe.

Who should read it?

- General readers and students: for an accessible entry into Holocaust testimony.

- Leaders/teams: to reset norms around respect and contribution.

- Anyone hurting: for a realistic, non-trivial hope from someone who earned the right to speak of it.

Why now? Because the currents Eddie warned about—humiliation stoking hatred, obedience without conscience—never stay dormant. And because, even now, “happiness is the only thing… that doubles each time you share it.”

Brief Historical Anchors

- Auschwitz-Birkenau victim estimates (~1.1 million total, ~1 million Jews).

- Holocaust total Jewish victims (~6 million).

- Eddie’s death and tributes (Guardian, ABC)

- ABIA award (Biography Book of the Year, 2021).