The Help by Kathryn Stockett is a landmark piece of historical fiction first published by Penguin Books on February 10, 2009. The novel vividly reimagines the lives of African American maids in the segregated American South during the early 1960s.

It quickly earned widespread acclaim, winning the Goodreads Choice Award for Best Fiction in 2009 and remaining on The New York Times Best Seller list for over 100 weeks.

Rooted in the genre of historical fiction, The Help delicately walks the tightrope between painful truth and heartfelt storytelling. Stockett, a white woman from Jackson, Mississippi, drew heavily on her childhood experiences—particularly her relationship with an African American domestic worker named Demetrie.

Notably, it took her five years to complete the manuscript and she faced 60 rejections before the novel found a publisher.

More than just a novel, The Help is a bold, honest, and complex conversation starter that reveals the painful realities of race, class, and gender in the Jim Crow South. Its emotional gravity, memorable characters, and dual-layered narrative structure turn it into a deeply resonant piece of literature.

Through carefully woven narratives, it forces us to reflect on power, silence, and courage—especially the courage required to speak uncomfortable truths in a hostile world.

Table of Contents

Plot Summary of The Help

Setting the Stage: 1960s Jackson, Mississippi

In the deeply segregated South of the 1960s, The Help takes us into the lives of Black maids working in white households in Jackson, Mississippi—a place where racism seeps through everyday conversations, household dynamics, and even bathroom placement.

The story begins with Aibileen Clark, an experienced and loving Black maid who’s currently working for Elizabeth Leefolt, caring for a little girl named Mae Mobley.

Aibileen has raised seventeen white children in her life, but Mae Mobley holds a special place in her heart—perhaps because she lost her own son, Treelore, not long before. His tragic death at a lumber mill, where he was crushed while working under unsafe conditions, planted a bitter seed in Aibileen. Despite the ache in her soul, she returns to caregiving because it’s the only work available.

Aibileen’s voice opens the novel, rich in dialect and raw emotion, showing the reader a hidden world of heartbreak, survival, and quiet strength.

Meanwhile, we meet Minny Jackson, Aibileen’s best friend and a firecracker of a woman. Minny’s talent for cooking is unmatched, but her sharp tongue often lands her in trouble with white employers. She’s recently been fired (again) after working for Miss Walter—mother of the infamous Hilly Holbrook—because Miss Hilly accused her of stealing.

In retaliation, Minny bakes a “Terrible Awful” pie that becomes one of the most wickedly clever moments in the entire story (though the details are a secret… for now).

Enter Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan, an awkward, idealistic white woman from a wealthy family who’s returned home after finishing college.

Skeeter’s ambitions stretch beyond finding a husband, unlike her childhood friends Hilly and Elizabeth. She dreams of becoming a writer. Haunted by the mysterious disappearance of her beloved maid Constantine—the Black woman who raised her—Skeeter slowly starts to question the deeply rooted racial injustices all around her.

Crossing the Line: A Dangerous Collaboration Begins

When Skeeter is offered a chance to write something original by a New York editor, Elaine Stein, she decides to take a dangerous leap: to tell the untold stories of Black maids working for white families in the South. But doing so isn’t just risky—it could destroy the lives of the women who dare to speak out.

At first, no one wants to talk. The danger is real. In Mississippi, just being caught talking to a white woman about such things could lead to job loss, arrest—or worse.

But slowly, Skeeter earns Aibileen’s trust, especially as they work together on a weekly cleaning column Skeeter’s ghostwriting for the local paper. Their bond begins to grow, rooted in respect and the quiet realization that change might only happen if someone is brave enough to speak up.

Minny, ever skeptical of white folks, is harder to convince. But after being fired and mistreated too many times, and needing to provide for her children despite an abusive husband, she agrees to contribute her voice.

Together, these three women begin a secret writing project: collecting true stories from the help—stories of neglect, kindness, racism, humor, and heartbreak. Some are horrifying; others are deeply moving. Together, they paint a complex, deeply human picture of life on both sides of the racial divide.

The Cost of Truth

As the manuscript grows, so does the danger. Skeeter becomes increasingly alienated from her social circle—especially Hilly Holbrook, the reigning queen bee of Jackson’s white society. Hilly, obsessed with maintaining racial “standards,” pushes for laws like the Home Help Sanitation Initiative, which would require every white home to have a separate bathroom for Black employees.

Her reasoning? “They carry different diseases.”

Aibileen and Skeeter are disgusted, and Skeeter even jokes, “Maybe we should build you a bathroom outside, Hilly”—a moment that costs her dearly. Hilly threatens to ruin Skeeter socially and professionally, and begins to spread rumors.

But the threat of being discovered isn’t just social embarrassment for Skeeter—it’s potentially life-altering for Aibileen and Minny. Yet the more they write, the more powerful the stories become.

Then something major happens: Yule May, Hilly’s maid, is arrested for stealing a ring to help pay for her sons’ education after Hilly denies her a loan. Her unjust arrest and brutal treatment becomes a turning point. More maids decide to come forward. Now they have enough stories to turn their secret writings into a full-blown book.

Publishing the Truth: A Risky Act of Rebellion

With stories from twelve maids now collected, Skeeter finishes the manuscript and sends it anonymously to the New York publisher. The book is titled Help—a direct nod to the voices that often go unheard. The identities of the maids and families are disguised, but in a small town like Jackson, people begin to recognize themselves.

The release of the book causes a quiet uproar. Though the town isn’t mentioned by name, everyone knows—it’s them.

Reactions are swift, though mostly whispered. White women begin suspecting their own maids of contributing to the scandalous tell-all. Some fire their help. Some lash out in passive-aggressive ways. Skeeter, meanwhile, becomes a pariah among her former friends. She’s removed from her role as editor of the Junior League newsletter. Her relationship with Hilly disintegrates entirely, turning bitter and aggressive.

Minny, perhaps the boldest voice in the book, included her infamous “Terrible Awful” story: the time she baked a chocolate pie with a very special, disgusting ingredient for Hilly as revenge for firing her unfairly. Though names aren’t named, Hilly knows. She threatens to sue the publisher but is ultimately too afraid—because any public denial would only expose her further.

Ironically, Minny’s revenge turns out to be their best protection. The fear of being associated with “that story” silences Hilly and keeps her from launching a full public campaign to expose the contributors.

Minny’s home life also begins to change. Her abusive husband Leroy, who suspects something’s going on, becomes even more violent. When the book is published, and the pressure at home grows unbearable, Minny does something radical: she leaves him. It’s a bold, terrifying move for a Black woman with children and no financial safety net—but it marks the beginning of her personal liberation.

Skeeter’s Awakening

For Skeeter, the publication marks the start of a new life. She receives a job offer from Harper & Row in New York. The dream she once dared to believe in is suddenly real. But it comes with a price: she must leave Jackson behind—her family, her home, and the people who raised her.

Her mother, Charlotte Phelan, who initially pushed her toward marriage rather than a career, finally shows unexpected support. Having fought her own quiet battles (including a cancer diagnosis), she encourages Skeeter to go, telling her: “Sometimes courage skips a generation. Thank you for bringing it back to our family.”

Skeeter’s romance with Stuart Whitworth, a politician’s son, had already begun to fall apart—he couldn’t handle her independence, let alone her controversial book. When he finds out the truth, he ends things for good. Heartbroken but resolute, Skeeter walks away from the life expected of her and toward the one she chooses.

Before she leaves for New York, she makes sure Aibileen is financially compensated for all her help with the book and arranges a hopeful goodbye. Skeeter knows that her book wouldn’t have happened without Aibileen’s bravery. Their parting is emotional but empowering—two women from different worlds, forever bonded by truth.

Aibileen’s Turn: A New Chapter Begins

The book’s publication leads to real consequences for Aibileen. Hilly, desperate for revenge, manipulates Elizabeth Leefolt into firing her. It’s heartbreaking—especially for Mae Mobley, who loves Aibileen more than anyone else in her life.

But Aibileen, though devastated, refuses to let Hilly win. She walks out of the Leefolt house with her dignity intact and something she never imagined having: the opportunity to become a writer herself. Encouraged by Skeeter and fueled by the journalistic fire that Treelore, her late son, once had, Aibileen decides to begin a new path—a future not built on cleaning other people’s messes, but on telling her own stories.

Ripples of Change: Quiet Acts of Revolution

The brilliance of The Help lies in its refusal to offer a neat, feel-good ending. Not everything is fixed. Racism hasn’t disappeared. Injustice remains woven into the very fabric of Jackson society. But small, meaningful changes begin to take root.

- Minny finds the strength to build a new life, free from abuse.

- Skeeter escapes the confines of her narrow world and begins using her voice nationally.

- Aibileen, once quiet and obedient, steps into a new role as a storyteller, finally honoring her son’s memory.

In a world where maids are expected to be invisible, these women become visible—courageously, boldly, and unapologetically. They may not be marching in the streets, but they are, in their own way, revolutionaries.

At the heart of The Help lies the transformation of its three central characters—Aibileen, Minny, and Skeeter—each of whom must confront personal fears, social norms, and deep grief to find their voices and agency.

Aibileen Clark: From Grief to Power

Aibileen’s journey is the most quietly powerful. When we meet her, she is a grieving mother simply trying to survive. Treelore’s death has hollowed her out. Working for the Leefolts is a form of numb repetition, but Mae Mobley’s innocent love reignites something human in her.

Over time, her friendship with Skeeter, and her decision to speak out, becomes an act of self-healing.

By the end, Aibileen is no longer afraid. She doesn’t beg for her job back. Instead, she embraces an uncertain future with hope. For a Black woman in 1960s Mississippi, walking away from the only kind of employment society allows her is nothing short of revolutionary. She becomes her own woman—not defined by grief, servitude, or silence.

Minny Jackson: From Fear to Freedom

Minny, known for her sass and sharp tongue, hides a painful secret: domestic violence at the hands of her husband, Leroy. Her humor and defiance are coping mechanisms, shields against a life that’s often brutal. But helping write the book—and specifically including the Terrible Awful story about Hilly—gives her back control. Her story, once a source of shame, becomes a source of power.

When Minny finally leaves Leroy, it’s not just a subplot—it’s a symbolic moment of liberation. She realizes she deserves better. That she doesn’t have to keep enduring pain for the sake of survival. That maybe, just maybe, a different life is possible.

Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan: From Compliance to Courage

Skeeter begins as someone torn between two worlds: the comfort of white privilege and the discomfort of her conscience. Her desire to write isn’t simply ambition—it’s a need to understand herself, her past, and the mysterious disappearance of Constantine, the maid who raised her.

What starts as curiosity becomes a moral awakening. Skeeter loses everything: her friendships, her reputation, even her relationship. But she gains something more important—integrity. She becomes an ally, not a savior, using her voice to amplify others rather than speak over them. Her final act of leaving for New York is a physical manifestation of the emotional journey she’s been on—walking away from what’s expected of her to pursue what’s right.

The Greater Message: What The Help Really Teaches Us

The Help is more than a novel about race—it’s a novel about voice. Who gets to speak? Who gets heard? Who gets silenced?

Stockett doesn’t pretend that one book could dismantle centuries of injustice. What she does show, with warmth and grit, is how everyday bravery—telling your truth, supporting a friend, quitting a job that disrespects your worth—can chip away at massive systems of oppression.

Some of the most powerful messages are tucked in the smallest moments:

- Aibileen whispering “You is kind. You is smart. You is important” to Mae Mobley, giving the little girl affirmation she won’t get from her own mother.

- Skeeter handing Aibileen money not out of pity, but as payment for real labor, finally recognizing her intellectual contribution.

- Minny realizing that her identity is more than just being someone’s wife or someone’s maid—it’s being a woman who matters.

The Aftermath

By the novel’s end, nothing is perfectly resolved. Hilly still wields power. Racism still defines Jackson. And many of the maids continue working in the shadows. But change has begun—not outside, but inside the characters.

Aibileen walks away from Elizabeth Leefolt’s house not as a fired maid, but as a woman with her head held high and her heart open to the future. Minny, though still burdened with challenges, starts dreaming again. Skeeter, once unsure of who she is, now walks into her new life with conviction.

These are not fairy-tale endings. They are realistic victories—small, personal revolutions that matter just as much as public protests. The courage to speak, to write, to walk away—these are the acts of defiance that move history forward, one voice at a time.

Even though The Help is a work of historical fiction set in the 1960s, its themes echo painfully into the present. The struggle for racial justice, the silencing of domestic workers, the dynamics of privilege and voice—these are not relics of the past. They’re very much alive today.

But the novel doesn’t leave us in despair. Instead, it offers a call to action: Listen. Speak up when it matters. Amplify those who are silenced. Choose discomfort over complicity.

And perhaps most importantly—remember the stories that history tries to erase.

Setting

The novel’s setting—Jackson, Mississippi during the early 1960s—is not just a backdrop; it is an ever-present character in the narrative. The city is deeply segregated, teeming with racist laws, unwritten social codes, and tensions threatening to explode. Locations like the Leefolt home, Celia Foote’s plantation-style mansion, and the colored neighborhood of Gessum Avenue serve to contrast the wealth disparity and entrenched racial barriers.

The setting’s historical weight enhances the urgency of the characters’ actions. Every whispered story, every trip on the segregated bus, every cautious meeting between Skeeter and the maids becomes a small act of rebellion against the racially charged landscape of the American South.

Analysis

a. Characters

Aibileen Clark

Aibileen is the emotional backbone of The Help. At 53, she has raised 17 white children but lost her only son, Treelore. Her love for Mae Mobley is deep and unconditional, offering the child warmth and affirmation absent from her own mother. When Aibileen tells her, “You is kind. You is smart. You is important” (Chapter 7), it is more than a tender moment—it’s a revolutionary act of emotional justice in a home of neglect.

She begins the novel cautious, even defeated—“A bitter seed was planted inside of me. And I just didn’t feel so accepting anymore” (Chapter 1)—but ends it empowered, even liberated, after finding her voice in Skeeter’s book project. Aibileen’s quiet dignity, inner growth, and eventual moral triumph illustrate how ordinary people can become catalysts for extraordinary change.

Minny Jackson

Minny’s firecracker temper is as legendary as her caramel cakes. She’s described by Aibileen as the best cook in Hinds County, yet her honesty often costs her employment. Her dynamic with her abusive husband, Leroy, adds a layer of domestic vulnerability beneath her sass. Minny’s defiance of Hilly Holbrook, specifically through the infamous “Terrible Awful” pie, reveals how humor can be weaponized against injustice.

Minny’s character deepens significantly in her relationship with Celia Foote. Through this unlikely friendship, she experiences trust and kindness from a white woman, forcing her to reevaluate long-held beliefs. When Celia defends her from her husband’s abuse, it’s a moment of shared sisterhood that pierces the racial divide.

Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan

Skeeter is the awkward, idealistic young white woman who challenges the racist status quo. Unlike her peers, she begins to question the ethics of how “the help” are treated, especially after discovering the mysterious departure of her childhood maid, Constantine. Her journey from naive college graduate to subversive author reflects the novel’s deeper themes of awakening and courage.

Skeeter’s pivotal moment comes when she refuses to bow to Hilly’s threats and chooses to publish the maids’ stories:

“What if – what if you don’t like what I write? What if it’s too much?”

“Then it’s too much,” Aibileen answers. “But it’s the truth” (Chapter 17).

Her narrative represents the uncomfortable but necessary role white allies can play in dismantling systemic racism.

Hilly Holbrook

Hilly is the embodiment of Southern racism masked in pearls and propriety. As president of the Junior League and the architect of the “Home Help Sanitation Initiative,” she symbolizes how institutionalized bigotry hides behind policy. Her vendetta against Minny and social manipulation reveals how power can be weaponized to uphold injustice.

Her character is terrifying precisely because it is so familiar—she’s not overtly violent, but her brand of racism is suffocatingly polite and brutally effective.

b. Writing Style and Structure

Kathryn Stockett’s use of multiple first-person narrators—Aibileen, Minny, and Skeeter—allows for a rich, layered view of life in 1960s Mississippi. Each voice is distinct and emotionally resonant: Aibileen’s narrative is poetic and spiritual, Minny’s is raw and biting, while Skeeter’s is thoughtful and observational.

The book’s use of dialect, particularly in Aibileen and Minny’s chapters, was a bold stylistic choice. While it adds authenticity, it has also sparked controversy for perpetuating stereotypes. Still, Stockett’s intent seems rooted in empathy, not caricature.

The pacing balances character introspection with narrative tension. Scenes like the bridge club gatherings, where casual racism drips from teacups, are crafted with subtle irony. The climactic publication of the maids’ stories and the ensuing fallout inject urgency into the final act.

Stockett also masterfully employs symbolism—such as the “bathroom” debate, which becomes a stand-in for systemic dehumanization.

c. Themes and Symbolism

Racism and Inequality

The dominant theme in The Help is racism—not in abstract terms, but in the deeply personal, everyday humiliations Black maids suffer at the hands of their white employers. From separate bathrooms to being accused of theft, the novel captures how normalized and insidious Jim Crow racism was in the South.

The character of Yule May, who is arrested for stealing a ring to fund her sons’ tuition, exemplifies the impossible moral choices faced by Black mothers.

Silence and Voice

Another central theme is the power of speaking up. For most of the novel, Aibileen and Minny live in fear—fear of losing their jobs, their freedom, or even their lives. Yet, through Skeeter’s project, they reclaim their agency. As Aibileen notes, “We are not just maids. We are people. We have stories too” (Chapter 29).

Motherhood

Motherhood is explored in complex and sometimes painful ways. Aibileen is more of a mother to Mae Mobley than Elizabeth Leefolt ever is. Minny, despite her tough exterior, fiercely protects her children. Skeeter, in contrast, struggles with her mother’s expectations and yearns for the nurturing Constantine once provided.

The “Terrible Awful” Pie

Minny’s revenge against Hilly—baking a chocolate pie with her own feces—is more than a comic moment. It is a grotesque but poetic act of resistance, symbolizing the rage and humiliation maids are forced to swallow daily.

d. Genre-Specific Elements

As a historical fiction novel, The Help is firmly anchored in its time and place. Stockett’s detailed evocation of 1960s Jackson—the clothes, the cooking, the hair salons, and the societal norms—adds texture and believability to the narrative. Dialogue is crisp and era-appropriate, while the world-building is precise without feeling pedantic.

The story doesn’t rely on fantasy or mystery conventions, but it adheres to the Southern Gothic tradition with its oppressive atmosphere, hypocritical characters, and themes of moral decay beneath polished exteriors.

Ideal Audience

The Help is a must-read for fans of character-driven stories, historical fiction, and social justice literature. It’s especially valuable for readers seeking narratives about allyship, racial healing, and women’s resilience across racial lines.

Evaluation

Strengths

1. Authentic Emotional Resonance

One of The Help’s greatest strengths is its emotional honesty. From Aibileen’s grief over her son—“It just wasn’t enough time living in this world” (Chapter 1)—to Skeeter’s growing moral discomfort with her social circle, the emotional arcs feel deeply human. The book does not rush its character development, allowing readers to truly sit with their fears, choices, and consequences.

2. Multiple Perspectives

Stockett’s decision to alternate chapters between Aibileen, Minny, and Skeeter adds multidimensionality. It offers a nuanced look at the lives of both the oppressed and the well-intentioned oppressor. The differing perspectives also highlight how racial injustice is experienced and rationalized across social lines.

3. Brave Narrative Framing

Writing a book centered on Black domestic workers through the lens of a white woman was undeniably risky. However, by focusing on the collaboration between Skeeter and the maids, the novel turns the act of storytelling itself into an act of rebellion. “We the help, we not the children. We grown women,” Aibileen says bluntly in one chapter—asserting agency where society has erased it.

Weaknesses

1. White Savior Critique

A common critique of The Help is its “white savior” undertone—Skeeter, a privileged white woman, becomes the catalyst for change in the lives of Black maids. While the story is collaborative, Skeeter often takes the lead in a way that unintentionally overshadows the voices she seeks to uplift. This raises the question: would the maids’ stories have mattered without white validation?

2. Dialect and Stereotyping

Stockett’s use of phonetic African American Vernacular English (AAVE) for Aibileen and Minny has drawn criticism. While intended to capture authenticity, some argue it reinforces caricature rather than character.

The lawsuit from Ablene Cooper, who claimed Aibileen was based on her without consent, amplified these concerns—though the case was dismissed due to the statute of limitations.

3. Sanitization of Brutality

The novel often skirts the harsher realities of racial violence in the Jim Crow South. There are threats, arrests, and emotional trauma—but no lynchings, rapes, or extreme brutality, which were also very real. Critics argue this softens the impact for white readers and prioritizes comfort over confrontation.

Impact and Reception

Sales and Cultural Influence

Despite (or perhaps because of) its controversies, The Help became a massive commercial success. As of 2011, over 7 million copies had been sold across formats, and it was translated into 35 languages. It stayed on The New York Times Best Seller list for over 100 weeks—a rare achievement for a debut novel.

The book opened important conversations about race, gender, and Southern history, especially for white readers who had never interrogated the realities of Black domestic labor.

Critical Reception

Critics were largely positive. The New York Times described it as “a button-pushing, soon to be wildly popular novel” that had “affection and intimacy buried beneath even the most impersonal household connections”. USA Today called it a “summer sleeper hit,” and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution called it “heartbreaking… a stunning début from a gifted talent”.

Still, many Black critics and scholars pointed out the oversimplification of systemic racism and the lack of authentic Black female voices in its creation.

Comparison with Similar Works

Compared to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye or Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, The Help is gentler and more commercial in tone. It shares thematic DNA with Barbara Neely’s Blanche on the Lam or Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes, blending social critique with Southern storytelling.

Yet, unlike those works authored by Black women, The Help can feel filtered through a white lens—even though it tries to spotlight Black voices.

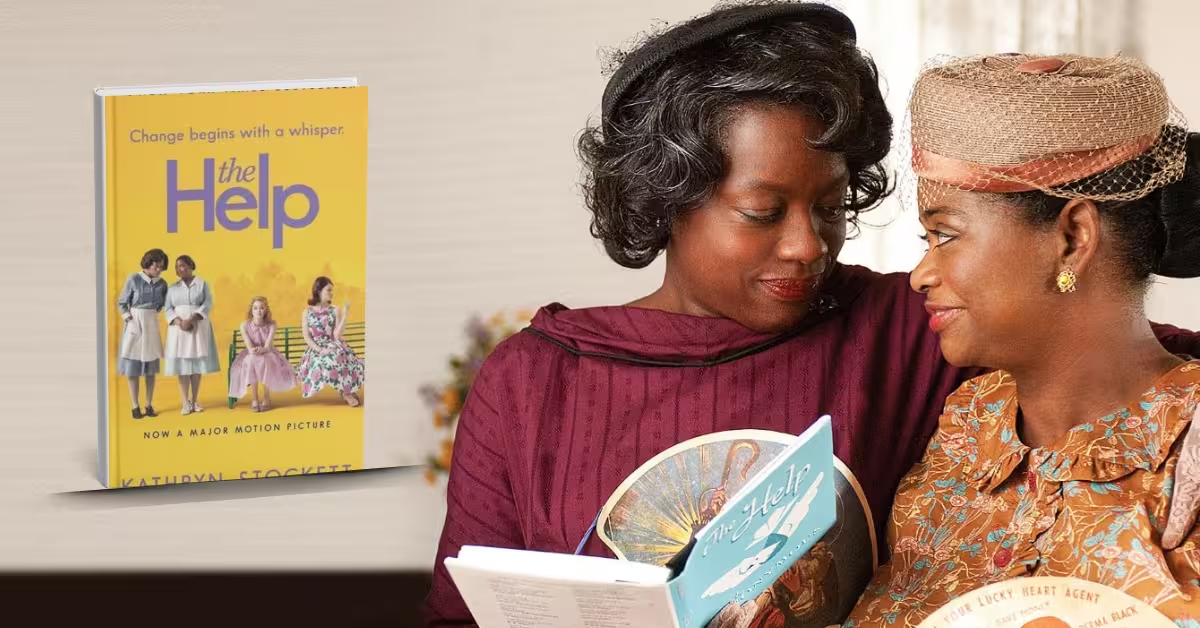

Adaptation (2011 Film)

The 2011 film adaptation, directed by Tate Taylor (Stockett’s childhood friend), featured Viola Davis as Aibileen and Octavia Spencer as Minny. Spencer won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, and the film was nominated for Best Picture.

While commercially successful, the movie amplified the novel’s “feel-good” tone. Viola Davis later expressed regret for participating, stating:

“I just felt that at the end of the day that it wasn’t the voices of the maids that were heard.”

(Source: The New York Times, 2018 interview)

The film’s glamour and emotional payoff drew in mainstream audiences but arguably sanitized the harshness of the reality it sought to portray.

Notable and Valuable Information

- Awards: Goodreads Choice Award (2009), Indies Choice Book Award, Townsend Prize for Fiction, among others.

- Author’s Journey: Stockett received 60 rejections over three years before publishing the book, which is now one of the best-selling novels of the 21st century.

- Cultural Debate: The lawsuit by Ablene Cooper sparked broader discourse on appropriation vs. inspiration, pushing publishers to reflect on authorial ethics in telling marginalized stories.

Personal Insight with Contemporary Educational Relevance

Reading The Help felt like listening to a grandmother’s whispered truths—painful, brave, and rooted in resilience. It didn’t feel like fiction. It felt like a window into a real, raw, and silenced world. And perhaps that’s what makes it so powerful: it dares to speak about the unspeakable with grace, wit, and heartbreaking honesty.

What struck me most was how Kathryn Stockett managed to illuminate the daily microaggressions Black maids faced—without relying on dramatic spectacle. Aibileen’s life isn’t one of rebellion, but one of endurance. The simple act of teaching Mae Mobley that she is loved—“You is kind. You is smart. You is important” (Chapter 7)—becomes an act of resistance. It made me reflect on the quiet heroes in our lives: the caretakers, janitors, bus drivers, and cleaning staff who often go unseen, unheard.

As an educator and learner in today’s increasingly global classroom, The Help reminds me why representation and voice matter. When we teach history without emotion, or literature without context, we lose the humanity behind the facts. The Help brings that humanity back into the room. It gives voice to the voiceless. It stirs the soul.

In contemporary education, we often speak of “equity” and “inclusion,” but what do those words really mean without action? This book can serve as a conversation starter in classrooms for students to explore power dynamics, the legacy of systemic racism, and the importance of telling one’s own story. It opens the door to examining:

- How language reinforces social hierarchies

- Why empathy in storytelling matters

- How courage can be collective, not just individual

In fact, I used passages from the novel in a student-led seminar on social justice literature. Many students were shocked—not at the cruelty, but at how “normal” the cruelty seemed to characters like Hilly. That realization triggered one of our most meaningful classroom discussions all semester.

The line that stayed with me is when Skeeter asks Aibileen: “Do you ever wish you could… change things?” And Aibileen replies with stillness, pain, and maybe sarcasm: “Oh no, ma’am, everthing’s fine” (Chapter 1). That moment—it’s a whole thesis on what it means to be unheard. It made me rethink how I listen to people around me, especially those whose voices aren’t in the spotlight.

The Help isn’t just a book—it’s an opportunity. An opportunity to hear. To reflect. To understand the weight of silence and the power of speech.

Conclusion

The Help by Kathryn Stockett is more than just a historical fiction novel—it is a powerful lens into the intersections of race, class, and womanhood in America’s Deep South. Set in 1960s Mississippi, yet emotionally resonant even today, it captures a slice of American history that is too often sugarcoated or silenced.

By giving voice to the maids who endured generations of quiet servitude, it urges us to remember that history is not only made by those in power, but also by those who dare to tell their truth.

Despite its imperfections—especially the critique that it centers a white protagonist in a story about Black suffering—The Help still manages to evoke deep empathy and critical thought. Its characters are unforgettable, particularly Aibileen, whose spiritual grace lingers long after the last page. The line, “We are not just the help. We are people,” (Chapter 29) becomes not only a declaration of dignity, but a challenge to the reader.

This book is a must-read for those interested in civil rights literature, women’s history, or simply stories that stir the soul. It’s also a valuable resource for classrooms, reading circles, and community discussions that seek to unpack the layers of privilege, silence, and resistance.

Final Reflection

In a world where the voices of the marginalized are still often ignored, The Help reminds us why listening—and amplifying—is one of the most powerful acts we can commit to. And though it may have sparked controversy, it also sparked necessary conversation. That alone makes it significant.

“All I’m saying is, kindness don’t have no boundaries.” —Kathryn Stockett, The Help (Chapter 34)

So whether you’re a student, an educator, a reader of historical fiction, or someone simply searching for a meaningful story, The Help will challenge your heart, sharpen your conscience, and stay with you long after you close its final chapter.