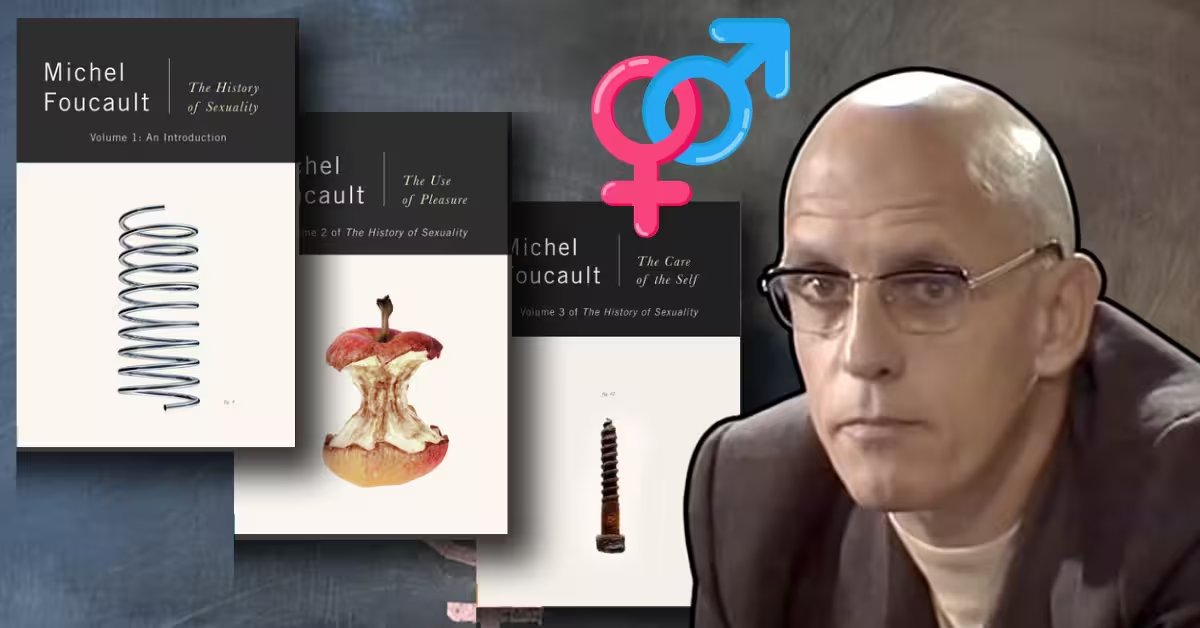

The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault is a groundbreaking and often controversial series that redefines how we think about sex, power, and the self. Far from being a purely biological instinct or a personal identity, Foucault argues that sexuality is a product of historical discourses, cultural norms, and institutional power.

Across its three core volumes, the series explores how modern societies have not repressed sexuality—as the common narrative suggests—but have instead generated an ever-growing body of knowledge and control around it. By tracing the evolution of sexual ethics from ancient Greece to modernity, Foucault reveals how sexuality has become a central site for the production of identity, moral subjectivity, and social regulation.

Bold, challenging, and deeply influential, The History of Sexuality continues to shape contemporary debates in gender studies, queer theory, philosophy, and the human sciences.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Published in 1976, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction stands as one of the most influential philosophical and historical texts of the 20th century. Authored by the French intellectual Michel Foucault—philosopher, historian, social theorist, and literary critic—this volume marked a radical departure from traditional ways of thinking about sex, power, and history. The book, originally in French as Histoire de la sexualité: La volonté de savoir, was later translated into English by Robert Hurley and published by Pantheon Books in 1978.

Categorized broadly under philosophy, cultural theory, and history, this foundational text occupies a space that bridges sociological insight and philosophical discourse. Foucault was no stranger to interrogating power structures—his previous works such as Discipline and Punish and Madness and Civilization had already cemented his status as a leading thinker of post-structuralism. However, The History of Sexuality was revolutionary in its proposition: sexuality was not a primal truth awaiting liberation, but rather a socially constructed discourse entwined deeply with mechanisms of power.

Foucault’s background—rooted in French structuralism, heavily influenced by Nietzschean genealogy and informed by extensive archival research—gives him a distinctive authority to explore themes that range from repression to biopolitics. As someone who was openly gay and wrote at the height of the AIDS crisis, Foucault’s personal and intellectual investment in the politics of sexuality imbues this text with palpable urgency.

At the heart of this first volume lies a provocative question: What if everything we believed about the repression of sexuality was a myth? Foucault confronts the “repressive hypothesis”—the widespread belief that modern Western society, especially since the Victorian era, has systematically silenced sex. He turns this assumption on its head by arguing instead that society has, in fact, talked endlessly about sex—not to repress it, but to regulate, categorize, and control it.

Foucault states, “Since the classical age, there has been a steady proliferation of discourses concerned with sex—specific discourses, different from the others, but not so much by their form as by their object” . From this assertion emerges the book’s core thesis: Sexuality has been used as a mechanism of power, intricately linked to knowledge production and social control.

Background of The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality is a seminal work that reshaped the discourse on human sexuality, challenging longstanding beliefs about repression, identity, and power. Originally planned as a six-volume series, only four volumes were published—three during Foucault’s lifetime and one posthumously. The project reflects Foucault’s deep engagement with the intersections of power, knowledge, and the body, offering a “genealogy” of how sexuality was conceptualized, regulated, and internalized throughout Western history.

The first volume, The Will to Knowledge (1976), debunks the widely accepted “repressive hypothesis”—the idea that Western society systematically suppressed sexual expression from the 17th to the 20th century. Instead, Foucault argues that sexuality became a subject of increasing discourse, categorized and scrutinized by emerging institutions such as medicine, psychiatry, and law. This volume lays the groundwork for his theory of “biopower,” a form of political power that governs populations by regulating bodies, health, and reproductive practices.

Volumes two and three—The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self (both published in 1984)—shift the analytical lens to ancient Greek and Roman societies. Here, Foucault explores how pre-Christian cultures constructed sexual ethics not through legalistic or repressive measures, but through self-mastery and moral reflection. These texts highlight how individuals shaped their identities through ethical practices, a concept Foucault terms “technologies of the self.”

The fourth volume, Confessions of the Flesh (2018), was published decades after Foucault’s death, drawn from nearly complete manuscripts held in his archive. It explores early Christian thought and its transformation of Greco-Roman ideas, emphasizing practices like confession and penitence as mechanisms of internalized control.

Throughout the series, Foucault emphasizes that sexuality is not a fixed biological or psychological reality but a social and historical construct shaped by changing discourses and power relations. He critiques the modern notion of sexual identity and instead focuses on the processes through which sexuality becomes a key site of personal and political regulation.

The History of Sexuality has profoundly influenced fields such as gender studies, queer theory, sociology, and the history of science. It offers a radical alternative to both conservative and liberationist narratives, making it one of the most provocative and enduring contributions to contemporary thought.

Summary of

Broad Overview

The History of Sexuality, Volume 1 is divided into five key sections, each meticulously unraveling the entanglement between sex, discourse, and power. These are: “We ‘Other Victorians’,” “The Repressive Hypothesis,” “Method,” “The Perverse Implantation,” and “Right of Death and Power over Life.”

The volume begins by challenging the notion that sex has been buried under moral and legal restrictions. On the contrary, Foucault suggests, sex became a focal point of discussion and analysis in various social institutions—law, medicine, psychiatry, pedagogy, and even the confessional.

The middle chapters focus on developing a “genealogy” of sexuality. Foucault traces how power has not merely censored sex but has instead incited its continuous articulation through a proliferation of discourses. “Power,” he argues, “is not something that is acquired, seized, or shared… it is exercised from innumerable points” . Thus, power is not monolithic but rather dispersed and relational.

The concluding chapters shift from sexuality per se to a broader philosophical discussion of power and biopolitics—the transition from sovereign power (which had the right to take life) to modern power (which manages life, through health, reproduction, and demographics).

Part One: We “Other Victorians”

Foucault begins by challenging what he calls the “repressive hypothesis“—the common belief that Western society, especially during the Victorian era, suppressed discussions of sexuality. Contrary to this view, Foucault argues that the 17th century onward actually saw a proliferation of discourses about sex, rather than a repression. In other words, rather than being silenced, sexuality was increasingly analyzed, documented, and categorized by institutions like the church, medicine, psychiatry, and the legal system.

Michel Foucault opens The History of Sexuality, Volume 1 with a provocative chapter titled “We ‘Other Victorians’,” immediately challenging one of the most enduring assumptions in Western cultural history: that modernity, particularly the Victorian era, was defined by sexual repression. This foundational chapter sets the stage for his broader argument that sexuality has not been silenced by society but rather produced and amplified through various forms of discourse, institutional power, and social norms.

This in-depth analysis explores the main arguments, key themes, and critical implications of this section, focusing on how Foucault dismantles the “repressive hypothesis”, rethinks the relationship between power and knowledge, and reframes sexuality as a central domain of modern subjectivity and social control.

1. The Repressive Hypothesis: A Myth of Modernity

One of the most striking features of “We ‘Other Victorians’” is Foucault’s attack on what he calls the repressive hypothesis—the belief that Western societies, especially since the 17th century, have sought to repress sexual behavior and speech. According to this narrative, sex was increasingly marginalized, silenced, and surrounded by taboo, only to be “liberated” in the 20th century through psychoanalysis, activism, and the sexual revolution.

Foucault asserts that this view is historically misleading and politically limiting. Far from being repressed, sex has been a constant object of scrutiny, regulation, and discourse—particularly through medicine, psychiatry, education, and religious confession. What appears to be silence is in fact a proliferation of language about sex. Thus, the modern world is not prudish but obsessed with categorizing, analyzing, and managing sexuality.

“The history of sexuality is not the history of repression, but of incitement to discourse.”

2. Power as Productive, Not Prohibitive

This critique of repression leads into one of Foucault’s most important theoretical contributions: a new conception of power. Traditional theories—whether Marxist, Freudian, or liberal—view power primarily as repressive. It says “no,” forbids, censors, and punishes. Foucault argues instead that modern power is productive: it creates categories, behaviors, norms, and identities.

In the context of sexuality, power does not simply ban sex—it stimulates discussion about it, creates classifications (e.g., “homosexual,” “hysteric,” “pervert”), and embeds sexuality in institutions like the family, school, and clinic. This is not to say power is benign; rather, it is diffuse, multi-layered, and deeply embedded in knowledge production. What seems like scientific understanding is also an exercise of control.

By rethinking power as relational and discursive, Foucault shifts the focus from what is forbidden to how we are shaped as subjects who speak, think, and act through the language of sexuality.

3. Confession and the Compulsion to Speak

A major focus of this chapter is the shift from acts to speech. While religious traditions—especially Catholicism—introduced confession as a religious ritual, modern institutions have adopted and secularized this compulsion to speak. In psychoanalysis, therapy, education, and even media, individuals are encouraged to reveal their deepest sexual truths, believing that in doing so they are being liberated.

Foucault argues that this is another form of disciplinary power: we are made to believe that truth lies in our sexuality, and that speaking it will set us free. But in fact, this demand for confession produces the very identity it claims to uncover. We internalize norms by narrating ourselves through them.

This reveals how sexuality became central to modern identity. Whereas earlier societies may have judged sexual acts, modern institutions judge sexual selves. The question is no longer “what have you done?” but “what kind of person are you?”

4. The Scientia Sexualis vs. Ars Erotica

In “We ‘Other Victorians’,” Foucault contrasts two historical models for understanding sex:

- Ars erotica: prevalent in ancient and non-Western societies, this “art of pleasure” emphasized experiential knowledge, sensuality, and the cultivation of eroticism.

- Scientia sexualis: dominant in the West since the 17th century, this model emphasizes truth through investigation, categorization, and confession.

Foucault critiques the scientific approach to sex for transforming desire into data. Modern sexuality is no longer lived—it is analyzed. The medicalization and pathologization of sexuality turn it into a disciplinary regime, where knowledge and control are inseparable.

By exposing this shift, Foucault challenges the assumption that modern sexual discourse is liberatory. Instead, he shows how science, therapy, and law have created a grid of intelligibility that tells us how to be sexual—and who we are because of it.

5. Sexuality as a Site of Modern Subjectivity

Ultimately, Foucault is not interested in sex per se but in how sexuality constructs modern subjectivity. He suggests that Western societies have made sex the site of truth about the self. Who we are is assumed to be defined, deep down, by our sexual desires. This belief shapes everything from identity politics to legal definitions of morality and freedom.

This is why the proliferation of sexual discourse matters: it’s not just talk—it’s power at work in the formation of modern selves. Sexuality becomes the “truth” we must discover, confess, and conform to. Thus, Foucault doesn’t just critique how we talk about sex; he shows how we’ve been made into sexual subjects through this talk.

Foucault concludes “We ‘Other Victorians’” with a powerful paradox: what we take to be our liberation from sexual repression may in fact be the deepest form of control. The more we talk about sex, the more we submit to the regimes that define, diagnose, and regulate it.

Rather than seeking to “free” sexuality, Foucault calls for a genealogical investigation—a history not of sex itself but of how we’ve come to believe in it, how it has been constructed as a problem, and how it functions as a central apparatus of modern governance.t.

Part Two: The Repressive Hypothesis

Part Two delves deeper into the “repressive hypothesis,” unpacking why this theory gained such widespread acceptance. Foucault proposes that believing we are repressed makes it feel liberating to talk about sex, which creates a paradox: the very act of discussing sexuality is framed as a form of resistance. Yet this discourse, he argues, is actually a mechanism of control.

Foucault identifies the “speaker’s benefit”—the psychological and social reward that comes from speaking about taboo subjects. This benefit gives the illusion of transgression but actually contributes to the continued regulation of sexuality. He outlines how the idea of repressed sexuality aligns with liberal and Marxist critiques of bourgeois morality, where the family becomes a central unit for reproducing both labor and sexual norms.

Foucault also critiques how the sexual sciences and psychoanalysis, notably the works of Freud, have institutionalized and normalized sexual speech. What was previously unspoken became dissected and scrutinized under the guise of liberating the subject. For Foucault, this reveals a shift from juridical models of power (laws forbidding certain acts) to disciplinary mechanisms (encouraging confessions, medical diagnosis, and surveillance).

Ultimately, this part builds on the first by arguing that modern societies are not sexually repressed but have cultivated a dense web of sexual discourse. Power now works not by silence but by inciting speech and controlling it through norms, institutions, and categories.

Part Three: Scientia Sexualis

In Part Three: Scientia Sexualis, Foucault contrasts two historical models for approaching sexuality: the ars erotica and scientia sexualis. The ars erotica, or “art of eroticism,” refers to ancient and non-Western systems (notably Chinese, Indian, and Greco-Roman traditions) that considered sex as an experience to be mastered, refined, and passed on through secrecy, practice, and experience. Knowledge in these systems was primarily experiential and esoteric.

In contrast, the scientia sexualis, which emerged in Western societies, is characterized by an institutionalized quest for truth through discourse. In this model, sexuality becomes something to be studied, confessed, examined, and ultimately “known” through methods of scientific inquiry, confession, and observation. Foucault argues that Western civilization transferred the domain of sex from mystical and bodily experience into a field of medical, moral, and psychological expertise.

A crucial element of the scientia sexualis is the confession, a tool inherited from Christian practices. Originally used in religious contexts to reveal one’s sins, confession evolved into a mechanism of self-surveillance and normalization in secular contexts. Foucault notes how sex became central to confession: it became the truth most worth uncovering, and individuals were increasingly compelled to speak the “truth” of their sexuality, whether in therapy, medicine, or education.

Importantly, confession doesn’t liberate the speaker; rather, it binds them to power. The person who confesses does not simply express themselves—they are analyzed, diagnosed, and ultimately normalized through institutional responses. This confessional dynamic helped institutionalize the modern notion of the “sexual subject”—someone who possesses a truth about themselves that must be spoken and interpreted by authority figures.

Foucault contends that what we often mistake as a movement toward sexual freedom is, in fact, a tightening of regulatory discourse. The emergence of sexual science and the medicalization of sex didn’t represent a break from repression but rather a refinement of how sexuality was monitored, produced, and governed.

This section helps transition the reader from a simplistic view of power as repression toward understanding it as productive and relational. By drawing attention to the way we seek “truth” through speaking about sex, Foucault shows how knowledge, power, and desire are intertwined in the Western construction of sexuality.

In short, Scientia Sexualis introduces a pivotal argument in Foucault’s theory of sexuality: that the West has developed a unique and powerful system of producing subjects through the demand for confessions about sex. This system disguises control as self-expression, ultimately shaping modern sexual identities under the banner of scientific truth and personal authenticity.

Part Four: The Deployment of Sexuality

In Part Four: The Deployment of Sexuality, Michel Foucault provides the structural core of his argument: that the concept of sexuality in Western society is not a natural or repressed truth but rather a strategic construct designed to serve broader power relations. He introduces the idea of the “deployment” (or dispositif) of sexuality as an assemblage of discourses, institutions, laws, and practices that aim to control and organize human behavior through the categorization of sex.

This section is divided into four chapters—Objective, Method, Domain, and Periodization—each explaining a key element in Foucault’s theoretical framework.

Objective

Foucault proposes that the study of sexuality must abandon the idea of sexuality as something innate or repressed. Instead, it should examine how sexuality was historically constructed as a domain of knowledge and experience. He identifies sexuality not as a pre-existing fact of human nature but as a historically specific product of power relations. These relations do not merely repress sexual behavior—they produce and organize it by creating norms and deviances.

Method

Foucault lays out a methodological shift. Rather than looking at sexuality through the lens of juridico-discursive power (i.e., laws that prohibit), he emphasizes a productive and relational model of power. Power is not simply top-down and repressive but diffuse, immanent in all social relations, and generative of new behaviors and identities. He urges scholars to examine power through its micro-practices, including how it shapes institutions like the family, schools, medicine, and psychiatry.

Domain

He identifies four strategic domains through which sexuality has been deployed since the 18th century:

- The Hysterization of Women’s Bodies – Women’s bodies were scrutinized, medicalized, and moralized, cast as inherently unstable and in need of regulation through science and marriage.

- The Pedagogization of Children’s Sex – Children’s sexuality became a focal point for surveillance, particularly in schools and families, framing them as sexually innocent yet dangerously curious.

- The Socialization of Procreative Behavior – Reproductive sex was positioned as a civic duty, reinforcing marriage, national growth, and demographic control.

- The Psychiatrization of Perverse Pleasure – Non-normative sexual practices were medicalized and categorized, giving rise to sexual identities like the “homosexual,” which were treated as pathologies.

These domains do not suppress sexuality but intensify and multiply the ways it is scrutinized and produced, thereby embedding it more deeply in social structures.

Periodization

Finally, Foucault challenges the idea that the 19th century marked a repressive age. Instead, he argues it was a period of intensification and proliferation of sexual discourse. The shift from religious to scientific discourse didn’t free sexuality but refined the mechanisms by which it was controlled and made visible.

In sum, The Deployment of Sexuality reframes how we understand the role of sexuality in Western society. It isn’t a hidden truth waiting to be uncovered but a regulatory mechanism of modern power, deeply tied to institutions and knowledge systems.

Part Five: Right of Death and Power over Life

In Part Five: Right of Death and Power over Life, Michel Foucault traces a pivotal transformation in how modern societies conceptualize and exercise power. Traditionally, power—especially sovereign power—was defined by its “right to take life or let live.” That is, monarchs or states could assert their dominance through acts of violence, including executions, wars, and punishments. This sovereign model of power was overt, centralized, and fundamentally rooted in death.

However, Foucault argues that this form of power has largely been replaced in modern societies by a biopolitical form of power, which he calls the “power to make live and let die.” Rather than focusing on death and coercion, modern power focuses on administering, optimizing, and regulating life—particularly through the management of bodies and populations. This shift signals a fundamental realignment in the relationship between power and the subject.

Foucault identifies two poles of this new form of power:

- Anatomo-politics of the human body – This refers to the discipline and surveillance of individual bodies, optimizing their capabilities and integrating them into productive systems (e.g., schools, the military, the workplace, hospitals). The body is subjected to detailed control, rendering it more efficient and useful.

- Bio-politics of the population – At the macro level, power focuses on the population as a biological entity. Birth rates, health care, life expectancy, hygiene, and disease control become central to governance. Policies and institutions emerge to manage life at the level of the collective.

These two poles work together to form what Foucault terms “biopower.” Unlike the older sovereign power, biopower is productive, not repressive: it generates norms and health standards, monitors populations, and steers behaviors in subtle and diffuse ways. This power is present in scientific discourse, public policy, medical institutions, and even sexuality itself.

Sex becomes central to biopower because it sits at the intersection of individual bodies and population management. Sexual behavior impacts reproduction, health, disease transmission, and moral order. Thus, the regulation of sexuality becomes a privileged domain for the exercise of biopower. Through norms, discourses, and surveillance, sexuality is both individualized and collectivized, governed at once by intimate scrutiny and state policy.

Foucault suggests that modernity is not marked by the repression of sexuality, but by its strategic deployment as an object of management and control. This is a core argument across the book: modern societies incite and organize discourse around sex, not to silence it, but to make it legible, controllable, and “productive” in terms of power.

He closes by noting that this emergence of biopower laid the groundwork for some of the most catastrophic events of the 20th century, such as racism, eugenics, and genocidal policies. When life itself becomes a political object, decisions about who deserves to live—or die—can be justified in terms of population health, racial purity, or national strength.

Structural Approach

The structure of the book is both thematic and argumentative. Each chapter builds logically on the last, constructing a cumulative critique of conventional wisdom regarding sex. Foucault uses a circular yet ascending method—each section revisits core questions while elevating the complexity and scale of the analysis.

This narrative approach can feel recursive but is deliberate: it mimics the way discourse itself circulates and multiplies within systems of power. By the end, readers find themselves not only rethinking sexuality but questioning the very foundations of knowledge and authority.

Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, Volume 1 is an intellectual jolt that reframes how we think about sex, truth, and power. Its most piercing argument is its refutation of the “repressive hypothesis”—the comforting belief that modernity has silenced sex and that we must now liberate it through discourse. Foucault turns this narrative on its head: “The question I would like to pose is not, Why are we repressed? but rather, Why do we say, with so much passion and so much resentment… that we are repressed?”.

This inversion is not merely rhetorical. Foucault meticulously supports his claim with historical evidence, showing how institutions—from the Church to psychiatry—have in fact fostered and incited discourse about sex. The confessional, for example, did not silence sex but rather insisted on ever more precise descriptions of sexual desire. “Everything had to be told. A twofold evolution tended to make the flesh into the root of all evil… from the act itself to the stirrings—so difficult to perceive and formulate—of desire”.

By linking power not to prohibition but to the production of knowledge, Foucault sets the groundwork for a new theory of governance: biopower. His analysis of the transition from sovereign to bio-political regimes—where power “fostered life or disallowed it to the point of death”—is one of the most cited frameworks in contemporary political theory.

Style and Accessibility

Foucault’s style is anything but casual. It is dense, spiraling, and often recursive. He builds arguments layer by layer, using repetition as a rhetorical strategy. While this might challenge readers unfamiliar with post-structuralist vocabulary, the payoff is intellectual clarity—paradoxically earned through conceptual complexity.

Nevertheless, the book is not inaccessible. Foucault often anticipates the reader’s confusion and repositions his key terms—like discourse, power, and sexuality—in different contexts to clarify their implications. He balances theoretical abstraction with vivid historical examples: the Catholic confessional, the psychiatrist’s couch, the regulation of children’s bodies in schools. This is not a purely philosophical treatise; it is a political and cultural history as well.

Themes and Relevance

Thematically, the book is a powerhouse. Beyond sex, it interrogates how we organize society, how we understand ourselves, and how power flows through the capillaries of everyday life. Foucault’s insights are chillingly prescient in the digital age. His idea that power operates not by forbidding but by inducing expression has become disturbingly relevant in an era of data surveillance and algorithmic profiling.

Moreover, Foucault’s concept of perverse implantation—the idea that labeling and categorizing sexual “deviants” (e.g., the hysterical woman, the masturbating child, the homosexual) created whole new subjects of power—resonates with current debates around gender identity and the medicalization of the body. “The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species,” he writes, signifying the moment sexual behavior was transformed into sexual identity.

Author’s Authority

Michel Foucault’s credibility as a theorist is beyond question. With rigorous training in philosophy and a career dedicated to archival and genealogical research, he brings an unmatched depth to his analysis. But what makes Foucault even more compelling is his positionality: as a gay man writing in the 1970s, he was both an observer of, and participant in, the politics of sexuality.

His method—a genealogical critique inspired by Nietzsche—rejects universal truths in favor of historical specificity. This gives his work both an academic and existential urgency. He does not just write about sexuality; he demonstrates how our very understanding of sexuality has been conditioned by centuries of power-knowledge formations.

4. Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

1. Groundbreaking Theoretical Innovation

One of the book’s most compelling strengths is its complete reframing of the sex-power relationship. Foucault discards the binary of repression versus liberation and instead offers a novel conceptual lens: power as productive rather than purely prohibitive. He writes, “Power is everywhere; not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere”. This inversion shifts the debate from moral to epistemological grounds, challenging liberal humanist ideals and offering a radical new way to understand society.

2. Interdisciplinary Relevance

Few texts transcend academic boundaries the way The History of Sexuality does. Whether you’re a student of sociology, philosophy, gender studies, literature, or political science, Foucault’s insights resonate deeply. His concept of bio-power, for instance—the governance of bodies and populations through subtle regulatory means—has influenced analyses of everything from healthcare to prison reform, from educational policy to algorithmic control.

3. Historical Depth

Foucault’s genealogical method is another strength. Rather than constructing a linear narrative, he traces transformations, discontinuities, and shifts in discourse.

The historical sections are rich in archival detail and theoretical nuance. His analysis of confession—particularly how the Christian ritual of penance laid the groundwork for modern forms of sexual surveillance—is eye-opening. “The obligation to admit to violations of the laws of sex… was decreed as an ideal at least, for every good Christian”.

4. Critique of Normativity

Perhaps the most humanizing aspect of the book is its relentless challenge to norms. Foucault dismantles the notion of a natural, universal sexuality. Instead, he shows how our very desires have been shaped, molded, and disciplined by discourse. This is not just academic theory; it’s deeply personal. For queer individuals, feminists, and anyone who’s been marginalized for their sexual identity, Foucault provides not only a critique but a liberation from the tyranny of “normal.”

5. Methodological Rigor

Foucault’s writing, while poetic at times, is never careless. Every claim is embedded in a broader intellectual architecture. He juxtaposes disciplines, defies categories, and interrogates the assumptions we take for granted. His refusal to offer easy answers may frustrate some, but it is a hallmark of his intellectual honesty.

Weaknesses

1. Accessibility and Style

Foucault’s prose is notoriously dense. His circular arguments and frequent use of abstract terminology can be alienating to readers unfamiliar with continental philosophy. Terms like “episteme,” “bio-power,” and “discursive formation” require careful unpacking, and the lack of concrete definitions can make the book feel elusive at times.

While these stylistic choices serve his theoretical ends, they pose a barrier to accessibility. As one reader aptly put it, “You don’t read Foucault, you wrestle with him.”

2. Lack of Empirical Data

Another frequent criticism is Foucault’s selective use of historical sources. Though he draws on medical treatises, legal documents, and religious texts, his method often avoids quantifiable data. For instance, while he critiques the idea of Victorian sexual repression, he doesn’t offer comprehensive statistics on censorship laws, psychiatric institutionalization, or public moral campaigns.

This opens the text to charges of anecdotal generalization. Some historians argue that Foucault cherry-picks examples that support his thesis while ignoring counter-evidence.

3. Limited Scope on Gender and Race

Although Foucault revolutionized thinking about sexuality, his treatment of gender is surprisingly limited. Feminist scholars have noted that while he deconstructs how men’s sexuality is shaped, he does not adequately address how women’s bodies have been historically and differentially regulated.

Similarly, issues of race and colonialism are largely absent from this volume, despite their profound entanglement with sexuality. For a theory that aims to uncover how power operates across social hierarchies, this is a notable omission.

4. Ambiguity Around Agency

Finally, there is the issue of agency. While Foucault brilliantly outlines how power operates through discourse, he often leaves readers wondering: What then? If all our desires are socially constructed, where is the room for resistance or authenticity?

His refusal to provide clear normative judgments—what is good, what is oppressive, what is liberatory—can feel unsettling. For those seeking practical or emancipatory solutions, Foucault’s work is more diagnostic than prescriptive.

5. Conclusion

Overall Impressions

Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, Volume 1 is not just a book—it’s an intellectual event. It dismantles comfortable narratives and forces us to confront the deeply embedded structures that govern our most intimate behaviors. His central argument—that sexuality has not been silenced, but rather has become the object of an endless and strategic discourse—compels us to rethink not only how we talk about sex, but also why we do so, and who benefits from these conversations.

Rather than treating sexuality as a biological given or moral battleground, Foucault reveals it as a social construct, shaped by complex networks of power, knowledge, and institutional control. In doing so, he liberates us—not by proposing a new dogma, but by making us suspicious of all dogmas, including those that masquerade as freedom.

As he writes with quiet provocation: “The central issue, then, is not to determine whether one says yes or no to sex… but to account for the fact that it is spoken about, to discover who does the speaking, the positions and viewpoints from which they speak”.

This insight alone justifies the book’s enduring influence. It’s not just a treatise on sex—it’s a meditation on modernity itself.

Strengths and Weaknesses Recap

Foucault’s strength lies in his theoretical originality, historical acumen, and ruthless interrogation of Western thought. He offers no comfort, no moral conclusion—but his refusal to simplify is what makes his work so valuable.

The primary weaknesses—accessibility, empirical gaps, and limited engagement with gender and race—should not be dismissed, but they also don’t diminish the book’s core contributions. Instead, they invite further scholarship and critique, making Foucault not a final authority, but a launching point for ongoing inquiry.

Who Should Read This Book?

This is not a book for the casual reader. It’s for those who seek to challenge their assumptions—academics, students, theorists, and intellectually curious readers willing to wrestle with complex ideas.

If you are involved in sociology, queer studies, critical theory, political philosophy, or feminist thought, this book is essential. But even beyond the academy, anyone who wishes to understand how power operates—not just from above but within—will find The History of Sexuality a revelatory text.

This book isn’t a map to sexual freedom. It’s a flashlight, exposing the mechanisms behind the maps we’ve already drawn.

Standout Quotes

- “Sexuality must not be thought of as a kind of natural given… but as a historical construct: an effect of power.”

- “Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power.”

- “The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species.”

Final Thought

Reading The History of Sexuality is like looking into a mirror that reflects not just your body, but your beliefs, your history, and your assumptions. It’s unsettling. It’s challenging. And it is absolutely necessary.