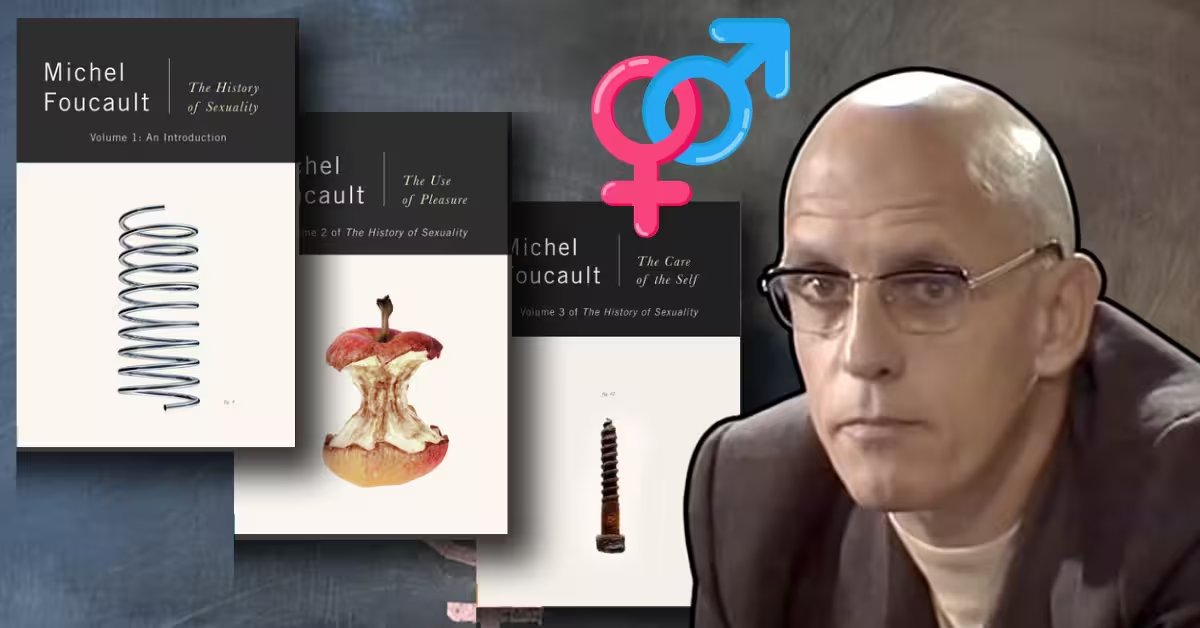

The History of Sexuality, Volume 3: The Care of the Self

Published in 1984, The History of Sexuality, Volume 3: The Care of the Self marks the final installment in Michel Foucault’s revolutionary series on sexuality, power, and subjectivity. Known in French as Le Souci de Soi, this work was released a few months before Foucault’s death, offering a reflective and poignant closing to a body of work that had redefined contemporary philosophy, history, and gender studies. Translated into English by Robert Hurley, and published by Pantheon Books, this volume is at once intimate and academic, bridging the personal and the political.

Michel Foucault was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. A French philosopher, historian, and theorist, his work interrogated institutions, discourses, and systems of knowledge that govern everyday life. By the time The Care of the Self was published, Foucault had already challenged conventional understandings of madness, punishment, and sexual repression.

In this volume, he shifts from institutions and discourses of control to focus on the ethics of the self—specifically, how individuals in antiquity practiced and internalized self-discipline in relation to sexuality. The book draws heavily on ancient Greek and Roman texts and reflects Foucault’s broader interest in how subjectivity is formed not only by power but also through practices of freedom.

Purpose and Central Thesis

At its core, The Care of the Self explores how sexuality in Greco-Roman antiquity was not seen primarily through a lens of law, sin, or repression, but as an arena for ethical self-formation. Foucault argues that sexuality was governed by an ethos of self-care, where individuals took responsibility for shaping their conduct in accordance with ideals of wisdom, moderation, and freedom.

Rather than being about prohibition, ancient sexual ethics were about balance, beauty, and control, performed through daily practices, relationships, and self-examination. As Foucault writes, “Concern for the self became increasingly important in the practice of liberty” .

Part I: Summary

The book is structured into three key chapters: “Dreaming of One’s Pleasures,” “The Cultivation of the Self,” and “Self and Others.”, “The Body”, “The Wife”, and “The Boys”. Each chapter deepens the investigation of how the ancient subject formed an ethical relationship to sex—not by obeying divine law, but by cultivating a lifestyle aligned with reason and virtue.

Foucault begins by tracing how, during the classical period, sexuality was integrated into a broader ethical practice of self-care (epimeleia heautou). Unlike the modern West’s emphasis on confession, truth-telling, and repression, Greco-Roman cultures focused on how to master desires and sustain self-control (enkrateia) through a regimen of behaviors.

He explores a variety of ancient authors—Plato, Xenophon, Galen, Epictetus, and Plutarch—uncovering how sex was part of a personal ethics rather than a moral absolute. In ancient medical texts, for instance, sexual activity is seen in relation to health, strength, and diet, not guilt or purity. Foucault notes:

“It is not a matter of forbidding sexual acts but of ensuring that they are properly regulated as part of the individual’s general conduct.”

The second chapter, “The Cultivation of the Self,” is the book’s heart. Foucault explains how elite men engaged in practices aimed at shaping the soul—writing, reading, dialogue, physical training, and sexual moderation. These were not rules imposed externally but chosen disciplines, forming what he called “technologies of the self.” Through these practices, the self becomes an object of transformation and care.

In the final chapter, “Self and Others,” Foucault turns his attention to interpersonal relationships—particularly friendship and mentorship—and how these social bonds acted as mirrors and frameworks for ethical development. In this dynamic, sexuality was not repressed, but channeled into meaningful ethical relationships.

Throughout, Foucault emphasizes that this ancient ethic of sexuality was not universal. It was gendered, classed, and primarily applicable to free, elite men. Nonetheless, it offered a radically different framework for thinking about sex—not as a sin to confess, but as an opportunity to exercise freedom.

The concept of “the care of the self” is essential to understanding Foucault’s later philosophy. By introducing practices of self-care, ancient Greeks integrated sexuality into broader ethical living. The history of sexuality here departs from the modern narrative of repression and sin. Instead, Foucault illuminates how ethics, sex, and freedom were intertwined through daily regimens, social bonds, and philosophical reflection.

We begin to see that sexuality was not merely a private matter, but a civic and personal duty—a space where the individual exercised autonomy and virtue. The care of the self became a social art, one tied to the pursuit of truth, balance, and health. These insights continue to shape how contemporary thinkers understand the history of sexuality, showing that even ancient cultures had sophisticated frameworks for sexual ethics, deeply entwined with freedom and self-mastery.

Introduction: Ethics and the Care of the Self

In the Introduction of The Care of the Self, Michel Foucault continues the shift he began in Volume 2—from a study of sexuality under modern disciplinary power to an exploration of ancient ethical practices. His primary concern is how individuals in antiquity shaped their moral selves through the “care of the self” (epimeleia heautou). He questions how sexual behavior was conceptualized not in terms of prohibition, but as a dimension of self-governance and ethical subjectivation.

Foucault outlines his methodological approach, emphasizing a shift from juridico-discursive models of power (laws, prohibitions, and repression) to techniques of self-formation. The central question is no longer, “What is forbidden?” but “How should one live?” This leads him to explore how ancient individuals used philosophy and lifestyle disciplines to align their desires, pleasures, and actions with broader values of health, beauty, and virtue.

He explains that Greco-Roman ethics did not rely on a universal moral law but rather on aesthetics of existence—crafting one’s life as a work of art. Here, sexual conduct is not an object of repression but a component of ethical refinement, where moderation, control, and wisdom were central. These ethics of pleasure required ongoing self-surveillance, training, and dialogue, especially within elite male culture.

Importantly, Foucault distinguishes “morality as a code of rules” from “morality as a practice of the self.” This sets the foundation for his historical and philosophical inquiry throughout the volume, emphasizing that sexuality must be understood within its cultural context—not merely as behavior, but as a structured domain of self-care, identity, and philosophical living.

Part One: Dreaming of One’s Pleasures

“Dreaming of One’s Pleasures” opens Michel Foucault’s deep dive into how Greco-Roman societies, particularly in the Hellenistic period, framed sexual conduct as a matter of philosophical and ethical self-regulation. Rather than viewing sexual pleasure as inherently sinful or shameful—as later Christian traditions would—this ancient worldview treated pleasure as something to be governed thoughtfully, not repressed.

Foucault’s central argument in this chapter is that ancient thinkers approached sexuality with a distinct attitude, where the primary concern was not morality in terms of rules, but ethics as an ongoing practice of freedom and care for the self.

Main Points and Arguments

1. Shift from Prohibition to Self-Stylization

Foucault emphasizes that ancient ethics did not operate through rigid prohibition but through the principle of moderation. Philosophical texts from the period encouraged individuals—primarily elite men—to examine their pleasures critically and place them within a balanced life structure. This formed part of what Foucault calls an aesthetics of existence, where one shaped life as a work of art, including sexual behavior.

Sex was not repressed; it was evaluated in terms of timing, frequency, and social context. A man who indulged too frequently in pleasure risked undermining his reason and social authority. Therefore, ethical sexual conduct was based on internal reflection and alignment with nature and reason.

2. Role of Philosophical Literature

Foucault analyzes how Greco-Roman philosophical texts—especially those from the Epicurean, Stoic, and Platonic traditions—approached dreams and desires. Dreaming about pleasure became a site of ethical concern because it indicated the state of one’s soul and discipline. If one dreamed too freely or too wildly, it was seen as a sign of ethical laxity.

This introspective attention to dreams shows how inner life and personal discipline were central to ancient ethical systems. Monitoring one’s dreams was akin to monitoring thoughts and actions—a way to keep desire in check even in unconscious life.

3. Freedom as Ethical Practice

Foucault reframes the notion of freedom in ancient ethics. Unlike modern liberal views, which equate freedom with individual rights and lack of restriction, ancient freedom was the capacity for self-mastery. A truly free man was not he who acted without constraint, but he who was not enslaved by desire. Thus, freedom and ethics were intimately linked through techniques of self-discipline.

4. Sexuality as a Site of Self-Knowledge

“Dreaming of One’s Pleasures” positions sexuality as a mirror of the self, not just a set of actions to be judged. How one felt, fantasized, or dreamed about sex was revealing of their moral condition. Ancient subjectivity was formed not through public confession (as in Christian ethics) but through private reflection, intellectual discourse, and daily discipline.

In “Dreaming of One’s Pleasures,” Foucault outlines a key transformation in the history of sexuality: the shift from viewing sex as something sinful to seeing it as an opportunity for ethical refinement. For ancient philosophers, sexual pleasure was neither to be indulged recklessly nor rejected entirely—it was to be curated within a well-ordered life. This approach emphasizes the role of self-care, introspection, and philosophical freedom, making sexuality an essential part of one’s ethical formation.

Part Two: The Cultivation of the Self

In Part Two: The Cultivation of the Self, Michel Foucault shifts the focus to the philosophical and practical techniques by which ancient individuals developed their ethical selves, particularly in relation to sexual conduct. He explores how Greco-Roman cultures viewed ethical living not simply as obedience to external laws but as a continuous, disciplined process of personal transformation.

This cultivation required ongoing attention, training, and care—what Foucault refers to as “askesis,” a set of spiritual or philosophical exercises designed to shape one’s thoughts, desires, and actions. Among the elite, this included reading philosophy, writing self-reflections, engaging in dialogue, and practicing bodily discipline. The goal was to bring the self into alignment with nature, reason, and societal harmony.

Sexuality played a central role in this process. Rather than being viewed as a sinful temptation to be suppressed, sexual pleasure was seen as a natural force to be mastered, integrated into a broader project of ethical self-governance. Excessive indulgence, or a failure to regulate desire, was considered a threat to the soul’s balance and to one’s social obligations as a rational citizen.

Foucault emphasizes that this ethical cultivation was deeply gendered and classed. The practices of the self were primarily directed at free, educated men, who were believed to possess the capacity and duty to transform themselves into virtuous subjects. Women, children, and slaves were largely excluded from this ethical discourse, as they were considered incapable of self-governance.

One of the key themes in this section is the individualization of ethics. Unlike religious morality based on divine commandments, ancient ethics emphasized personal choice, reflective practice, and philosophical inquiry. This autonomy of the subject did not imply freedom in the modern liberal sense, but rather a commitment to rational self-discipline within a clearly defined moral and social order.

Part Three: Self and Others

In Part Three: Self and Others, Foucault examines how ethical subjectivity was formed in relational contexts. Ethics, he argues, was not just about solitary introspection but involved a network of interpersonal and social relationships, especially among men. Friendship, mentorship, and even pedagogical relationships were essential to the care of the self.

Foucault explores the role of teachers, philosophers, and older mentors in shaping the ethical lives of younger men. These relationships often included both educational and erotic dimensions. The mentor guided the younger man not just intellectually but morally and emotionally, helping him learn how to regulate desire and cultivate virtue.

These practices emphasized reciprocity, responsibility, and guidance. Ethics was about more than controlling one’s passions—it was about how those passions were shaped and refined in interaction with others. The ideal relationship was one in which both parties pursued truth and self-mastery, avoiding domination or shame.

Foucault also addresses the gendered asymmetry of ethical relations. While relations between men were sites of ethical development, relations with women were often seen as problematic, requiring stricter discipline and distance. Women were not equal partners in ethical cultivation; instead, their sexuality was something to be governed as part of a man’s self-regulation.

The broader theme here is that ethical formation required a social milieu—one where behavior could be mirrored, corrected, and improved. These dynamics resonate with modern ideas of accountability and mentorship but are rooted in ancient practices of virtue ethics and the stylization of existence.

Part Four: The Wife

In Part Four: The Wife, Michel Foucault explores how the role of the wife was conceptualized within Greco-Roman sexual ethics and how this reflected broader dynamics of gender, power, and self-mastery. The wife was central to the ethical life of the male citizen, not because of her autonomy, but as a reflection of her husband’s ethical standing.

Foucault highlights that ancient ethics did not emphasize reciprocal rights or equality within marriage. Instead, they focused on the husband’s responsibility to govern the household in a way that maintained order, stability, and virtue. This included the disciplining of his wife’s sexuality, which was seen as a direct extension of his own moral authority. Her behavior was not evaluated on its own terms but as a sign of the husband’s capacity for control and self-restraint.

A key concern was chastity and fidelity, not only for its moral implications but because it reflected on the husband’s character. Foucault underscores how texts from the period portrayed the ideal wife as modest, silent, and confined—her virtue defined by obedience and invisibility. The husband’s ethical task was to cultivate these virtues through rational governance, not coercion.

Sexual relations within marriage were also ethically coded. A man was expected to engage with his wife sexually but with moderation and self-control. Excess, even within marriage, was seen as morally degrading. Thus, the wife became a mirror for the husband’s ethical success or failure in regulating both his and her conduct.

Foucault uses this analysis to reinforce his broader argument that sexual ethics in antiquity were deeply tied to power relations, but expressed through codes of conduct, not law. The wife was not a subject of ethics but an object of the husband’s ethical formation.

Part Five: The Body

In Part Five: The Body, Foucault turns his attention to the philosophical and medical discourse on the body as a site of ethical practice in Greco-Roman culture. The body was not seen as a sinful vessel to be condemned, as in later Christian thought, but as a domain to be disciplined, trained, and balanced.

Health, strength, and harmony were the ideals. The body’s functions—including its sexual desires—had to be managed through regimes of diet, exercise, and sexual moderation. Foucault shows that bodily care was part of the larger ethical project of forming the self. The body was a tool for virtue, requiring attention but not indulgence.

Ancient medicine provided a framework for understanding how desires could disturb the balance of the body and soul. Sexual activity, for instance, could deplete vital energies or stir passions that interfered with rational thought. Therefore, bodily practices were both ethical and medical: they sustained physical integrity and moral clarity.

This perspective challenges the modern dichotomy between body and soul. For the ancients, the body was not a base entity opposed to reason, but a partner in ethical living. Foucault emphasizes that caring for the body was a form of self-respect and a necessary condition for the care of the self.

Part Six: Boys

In Part Six: Boys, Foucault examines the ethics surrounding pederastic relationships in Greek antiquity—sexual and educational bonds between adult men and adolescent boys. These relationships were ethically complex, seen as both a source of personal development and a potential danger to virtue.

Foucault stresses that ethical concern centered on power, status, and self-control, not the nature of the sexual act. The older man (erastes) was expected to exercise restraint and educational intent, guiding the younger boy (eromenos) toward virtue, not merely pursuing him for pleasure. The risk lay in becoming overly passionate or losing one’s self-mastery, which would damage one’s reputation and ethical standing.

For the boy, the ethical challenge was to maintain modesty and avoid shame, even as he was pursued. Submitting too easily or showing enjoyment risked moral and social degradation. These roles were not symmetrical; the older man held the power, but his ethical challenge was greater—he had to lead by example and model virtuous conduct.

Foucault shows how these practices were framed as ethical education, not merely sexual behavior. They were embedded in systems of mentorship, rhetoric, and social honor. Unlike modern views of sexuality grounded in identity, the ancients focused on actions, relationships, and their ethical implications.

This section reinforces Foucault’s broader point: sexual conduct in antiquity was governed by a matrix of aesthetic, ethical, and political concerns, not religious guilt or universal prohibitions. The focus was on how one acted, with whom, and with what degree of self-control and intent.

Part II: Critical Analysis

Evaluation of Content

Foucault’s final volume in the History of Sexuality series marks a notable evolution in his intellectual journey. Where the first volume focused on institutions and discourses—psychiatry, the church, the law—Volume 3 places the individual at the center of ethical life. This is a powerful and subtle shift. It’s not that Foucault abandons the idea of power, but he relocates it within the self, asking how individuals in ancient societies fashioned their own moral codes without the pressures of religious or legal condemnation.

His use of classical texts is both precise and expansive. Drawing from sources such as Epictetus, Plutarch, and Galen, Foucault reconstructs a nuanced picture of how sex was problematized—not as transgression but as excess or imbalance. He writes:

“Pleasure was not condemned, but it had to be contained, scrutinized, and aligned with the health of the body and the harmony of the soul” (p. 50).

This evidential strategy reveals a crucial insight: ancient sexual ethics were built not on prohibition but on self-discipline. This is a major contribution to both the history of philosophy and the history of sexuality, presenting a model of morality rooted in personal reflection rather than institutional control.

Foucault’s arguments are supported through a careful interpretive methodology. He doesn’t merely cite ancient texts—he enters into dialogue with them. This engagement avoids anachronism and shows how ancient concerns about the self, moderation, and social roles formed a coherent ethical system.

Style and Accessibility

The writing in The Care of the Self is dense but lyrical. Foucault’s language, even in translation, retains a contemplative rhythm. The prose can be demanding, as he moves between historical analysis, philosophical commentary, and textual interpretation. But this is also its brilliance. Foucault respects the intelligence of his readers. He invites them into a shared exploration of freedom, power, and selfhood.

Still, for those unfamiliar with ancient philosophy or the previous volumes, this book may be less accessible. It helps to have a foundational understanding of Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Greco-Roman medical ethics. Yet, this challenge is not a flaw; it reflects Foucault’s ambition—to speak with seriousness about what it means to live ethically.

For those deeply interested in the philosophy of sexuality, Foucault’s work is not only essential but foundational. It’s not a guidebook, but a philosophical meditation on the forms that freedom can take, especially when one turns inward to care for oneself.

Themes and Relevance

Among the book’s dominant themes is self-mastery—not in a Nietzschean sense of domination, but in a Socratic mode of measured, ethical living. This resonates powerfully today. In an age saturated with performative identity and social surveillance, the idea of shaping the self through discipline, not confession, offers a radical alternative.

Foucault is also ahead of his time in emphasizing ethics without universalism. The ethics of the self he describes are not prescriptive for all; they are historically situated and contingent, shaped by class, gender, and cultural norms. As he notes:

“The subject of pleasure had to be a subject of discipline, not repression—a subject who masters himself and guides others through example” (p. 112).

This allows his work to speak across boundaries. Whether in feminist theory, queer studies, or modern psychology, his critique remains relevant. By shifting the discourse from law to lifestyle, sin to care, repression to reflection, Foucault opens new ethical and intellectual pathways.

Author’s Authority

Foucault’s credibility as a scholar of ancient texts may be questioned by classical purists, as he is not trained as a classicist. However, his philosophical and genealogical method justifies his approach. He reads ancient sources not to reconstruct them perfectly, but to trace how their ideas intersect with contemporary concerns.

His interpretations are radical, yes—but they are grounded in textual engagement, historical sensitivity, and intellectual integrity. Foucault does not misuse history; he repurposes it to reveal what is at stake in the present. And in doing so, he affirms his position not just as a theorist, but as a philosopher of enduring value.

Part III: Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

1. A Transformative Rethinking of Ethics and Sexuality

One of the most compelling strengths of The Care of the Self is its radical reconfiguration of sexual ethics as a practice of freedom rather than a regime of repression. Instead of focusing on rules or prohibitions, Foucault draws attention to the subtle ways in which ancient individuals shaped themselves through ethical practices. As he writes:

“The relation to the self, to the pleasures, to one’s partner, and to the truth, was formed within a network of practices in which the subject constituted himself as an ethical subject” (p. 29).

This powerful shift reorients how we view sexuality. It’s not a site of guilt or confession, but a platform for self-formation. That alone situates this volume as one of the most intellectually liberating contributions to the history of sexuality.

2. Bridging Philosophy, History, and Literature

Foucault’s erudition allows him to bridge disparate domains: the philosophy of Seneca and Epictetus, the medicine of Galen, and the rhetorical ethics of Plutarch all come together under his deft analytical gaze. He doesn’t just analyze—they are brought into conversation, revealing how these thinkers approached sexuality as part of a broader ethical system. His interpretive capacity is a true intellectual feat.

3. A Blueprint for Non-Oppressive Ethics

In our contemporary world—where identities are often shaped by surveillance, algorithms, and moral policing—Foucault’s ancient blueprint offers an alternative. The “care of the self” emphasizes autonomy, introspection, and the ability to resist external domination without withdrawing from ethical responsibility. It’s a rare philosophical offering: ethical without being moralistic, individual without being selfish.

4. Precision of Language and Conceptual Innovation

Foucault’s coinage of phrases like technologies of the self, aesthetics of existence, and problematization has left a profound impact on modern thought. His discussion of how subjects are formed—not just oppressed—continues to influence disciplines as diverse as sociology, gender studies, political theory, and psychotherapy.

Weaknesses

1. Limited Scope of Subjectivity

One of the most frequent critiques of The Care of the Self is its narrow focus on elite, male subjects. While Foucault acknowledges this, noting that his study is limited to the “free adult male,” it nevertheless risks reinforcing the idea that only such individuals had access to ethics or self-care. The voices of women, slaves, and non-citizens are mostly absent from this narrative.

While this may reflect the limitations of his sources, it also raises ethical questions about inclusion. The history of sexuality deserves a broader spectrum of voices, especially those marginalized by ancient and modern structures alike.

2. Accessibility and Density

Foucault’s style, though brilliant, is not always accessible. His long, winding sentences and frequent philosophical allusions can make it challenging for general readers to penetrate the text. While this is not an inherent flaw, it does create a barrier. The Care of the Self is intellectually demanding—one must read slowly, reflect deeply, and often reread entire sections to absorb the nuance.

3. Historical Interpretation vs. Philosophical Application

Some critics, particularly historians of antiquity, have questioned whether Foucault’s interpretations of Greco-Roman texts occasionally sacrifice historical fidelity for philosophical insight. His readings are thematic and conceptual, often glossing over historical context in favor of contemporary resonance. While this makes the book deeply relevant, it does open it to charges of anachronism.

That said, Foucault was not aiming to write a textbook on Greek sexuality. His goal was genealogical—to trace how concepts like “the care of the self” emerged and could be mobilized differently than in our modern framework. In that regard, even his speculative interpretations feel intellectually valid and philosophically rich.

Part IV: Conclusion and Recommendation

Overall Impressions

Reading The Care of the Self is not simply an intellectual exercise—it is an invitation into a different mode of existence. One cannot help but emerge from its pages with a deeper understanding of not only ancient sexual ethics but also of how we, today, might reimagine freedom, care, and subjectivity. What struck me most in this work was Foucault’s profound ability to see beyond the institutional gaze. He moved away from discussing how we are watched or controlled by others, and turned his focus inward, asking:

“What if freedom was not the absence of power but a relationship to the self carefully nurtured through ethical practice?” (p. 34).

In a world obsessed with rights, exposure, and authenticity, Foucault offers an ethic that is introspective, disciplined, and beautifully pragmatic. His turn to antiquity is not escapism—it is a search for alternatives, blueprints from the past that challenge the idea that we must either obey external law or descend into moral relativism. The ancient world, as Foucault shows us, had a third option: the art of living.

What Foucault accomplishes in The Care of the Self is monumental. He not only reshapes how we view sexuality in antiquity; he reshapes how we think of ethics as a lived practice, rooted in self-attention, relational responsibility, and embodied knowledge. This book is both a history and a mirror.

Who Should Read This Book?

This is not a book for everyone, and I say that with honesty and care. The History of Sexuality: The Care of the Self is best suited for:

- Philosophy students and scholars, particularly those interested in ethics, classical philosophy, or post-structuralism.

- Gender and sexuality theorists who seek to understand the genealogical roots of contemporary sexual discourse.

- Sociologists and political theorists invested in exploring how subjectivity is shaped by power and practice.

- Psychotherapists, ethicists, and educators who believe in the transformative role of self-discipline, reflection, and ethical development.

- And finally, any curious, patient reader willing to engage in a demanding but deeply rewarding encounter with one of the great minds of our time.

However, casual readers unfamiliar with philosophical terminology or classical texts may struggle without support. I would recommend pairing this text with guided commentary or secondary resources, such as David Halperin’s One Hundred Years of Homosexuality or Pierre Hadot’s Philosophy as a Way of Life.

Final Word

In a time when sexual ethics are often discussed in terms of legality or identity, Michel Foucault’s The Care of the Self reminds us that there is another way to understand ourselves—not through rules, repression, or revelation, but through care. Sexuality, in this vision, becomes an art. The subject is not coerced into truth but cultivates it through daily acts, through friendships, through moderation and reflection.

“To care for oneself is not simply to know oneself, but to constitute oneself as an ethical subject of one’s own conduct” (p. 45).

This final volume in the History of Sexuality is not just a study of the past. It is a call to rethink what it means to live well, to love wisely, and to be free—not from the world, but within it. Foucault does not prescribe a path. He offers a map, drawn from the ancients, for us to walk with awareness, with dignity, and, above all, with care.

Comparison Table: Foucault’s History of Sexuality Volumes 1–3

| Aspect | Volume 1: The Will to Knowledge | Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure | Volume 3: The Care of the Self |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period Focus | Modern Western society (17th–20th c.) | Classical Greece (5th–4th c. BCE) | Late Greco-Roman Empire (1st–2nd c. CE) |

| Central Question | How is sexuality shaped by power and discourse? | How did the Greeks problematize sexual pleasure? | How did individuals become ethical subjects of sexuality? |

| Main Concept of Power | Repressive vs. productive power; bio-power | Ethical self-mastery, not institutional control | Self-care as ethical formation; relational power |

| Key Mechanism | Confession, discourse, surveillance | Moderation (sōphrosynē), self-control (enkrateia) | Askesis, techniques of the self, care of the body |

| View of Sexuality | Not repressed but produced and managed | Integrated into ethical self-regulation | A domain for personal and relational ethical cultivation |

| Moral Framework | Discursive regulation and normalization | Aesthetic ethics: conduct aligns with virtue | Philosophical ethics: shaping the self through practices |

| Role of the Self | The self is constructed through discourse and normativity | The self is governed through reason and self-restraint | The self is cultivated as an ethical and aesthetic project |

| Role of Institutions | Church, psychiatry, state, education | Family, medicine, philosophy | Philosophy, pedagogy, household governance |

| Gender & Sexual Roles | Sex is categorized and classified (e.g. “homosexual”) | Male-centered ethics, women excluded from discourse | Gendered ethics; male governance over women and boys |

| Ethical Substance | Desire as a truth to confess | Pleasure as something to regulate | The self as a subject of ongoing cultivation |

| Mode of Subjection | External law, religious norms, confession | Rational conduct, philosophical ideals | Self-governance, internalization of philosophical practice |

| Goal (Telos) | Normalized, classified sexual subject | Harmonious life, personal virtue | Autonomy, freedom, ethical beauty of life |

| Signature Theme | The “repressive hypothesis” is false—power incites sexuality | Pleasure becomes ethical through moderation | The care of the self is the key to ethical living |

| Philosophical Influence | Structuralism, psychoanalysis, Marxism | Greek ethics: Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates | Stoicism, Roman thought, Seneca, Epictetus |

Reception and Criticism of The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality has become a landmark work in critical theory, influencing diverse academic fields such as gender studies, sociology, philosophy, and cultural history. However, its reception has been as complex and multifaceted as its themes. This analysis covers the scholarly and critical reception of the series, key debates it ignited, and its enduring impact on contemporary thought.

Scholarly Reception

Upon its release, The History of Sexuality sparked vigorous debate. Volume I (The Will to Knowledge) challenged the dominant “repressive hypothesis,” which argued that Western societies had suppressed sexuality since the 17th century. Instead, Foucault claimed that sexuality had become more openly discussed—through science, medicine, and confession—and was deeply intertwined with power structures.

This central thesis received both acclaim and criticism. Alan Soble praised Foucault for revolutionizing the study of sex by highlighting the social construction of desire and sexuality. He noted that the work inspired the development of queer theory and genealogical methods in philosophy and history.

Similarly, the philosopher Judith Butler cited Foucault’s work as foundational to her theory of gender performativity in Gender Trouble, though she later critiqued his romanticization of pre-modern sexual “innocence.”

Criticism and Controversy

Several scholars took issue with Foucault’s methodology and conclusions. Classicist Patricia O’Brien criticized the later volumes—focused on Greco-Roman ethics—for lacking the rigorous methodology seen in Discipline and Punish. Likewise, Peter Gay noted that while Foucault’s inversion of conventional ideas was provocative, it lacked empirical grounding and relied heavily on anecdote.

Sir Roger Scruton, a conservative philosopher, rejected the idea that sexual morality is culturally relative. He argued that all societies inevitably “problematize” sex, and thus Foucault’s claim of cultural specificity was flawed. Similarly, José Guilherme Merquior acknowledged Foucault’s originality but argued that his analysis of Greek homosexuality was inferior to Kenneth Dover’s.

Camille Paglia in her Sex, Art, And American Culture, Chapter 20, went even further, branding The History of Sexuality a “disaster,” accusing Foucault of indulging in speculative and unfounded theorizing. David Halperin, by contrast, saw the book as transformative, marking a turning point in the study of sexual morality akin to Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals.

Feminist and Queer Theory Responses

The feminist response was divided. Germaine Greer supported Foucault’s claim that what is often seen as liberation was actually a deeper form of regulation. However, other feminists, like Page duBois, were more critical, asserting that Foucault’s analysis reinforced male-centric philosophical traditions and failed to adequately examine women’s sexual subjectivity.

Queer theorists, meanwhile, found in Foucault a liberatory potential. Dennis Altman used Foucault’s ideas to argue that the modern homosexual identity is a social invention—a product of historical discourse rather than innate essence.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Despite the criticism, The History of Sexuality remains deeply influential. It introduced the concept of “biopower”—the regulation of life by political and medical institutions—which has become central to disciplines like bioethics, sociology, and public health. The idea that sexuality is not simply natural but shaped by power, discourse, and historical processes revolutionized how scholars approach identity and the body.

The posthumous publication of Volume IV: Confessions of the Flesh in 2018 reignited interest in Foucault’s unfinished project, delving into Christian notions of confession and desire. Although Foucault had opposed posthumous publication, his estate released the book to ensure scholarly access.

Conclusion

The History of Sexuality has had a polarizing but undeniably powerful impact. It redefined sexuality not as a biological constant but as a cultural and political construct. Critics have debated its historical accuracy, theoretical rigor, and philosophical implications, but few deny its significance in shaping modern understandings of power, identity, and human desire.

Whether viewed as flawed or foundational, Foucault’s exploration of sexuality remains a cornerstone of critical thought—and a source of ongoing debate across disciplines.