When a storm knocks out the lights, a teacher alone in a remote cabin discovers a knife-clutching girl in her toolshed—and a past that won’t stay buried. The problem The Intruder solves? It gives readers a fast, emotionally resonant way to think about how trauma, trust, and moral lines blur under pressure—without graphic content or gratuitous violence (the author flags content warnings and keeps things “as family-friendly” as possible).

The Intruder shows how one “infinity promise” can hold a broken life together—until a stranger, a storm, and a terrible secret force that promise to its limit.

McFadden anchors the thriller in concrete, vivid beats: the unforgettable window scare—“There’s a pale face staring at me from outside my window.” ; the shed scene where the “lump” under a blanket lowers to reveal “a girl… holding a knife.” She also sets expectations in an Author’s Note, pointing readers to official content warnings on her site.

Publication details confirm the 2025 release across hardcover/audiobook, with Poisoned Pen Press and Sourcebooks listing formats, dates, and pages.

The Intruder is best for fans of psychological thrillers who crave propulsive twists, morally sticky choices, and a cabin-in-the-woods pressure cooker. Not for readers seeking cozy mystery vibes, graphic gore, or slow, literary introspection; the book is engineered for velocity, tension, and gut-punch reveals.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

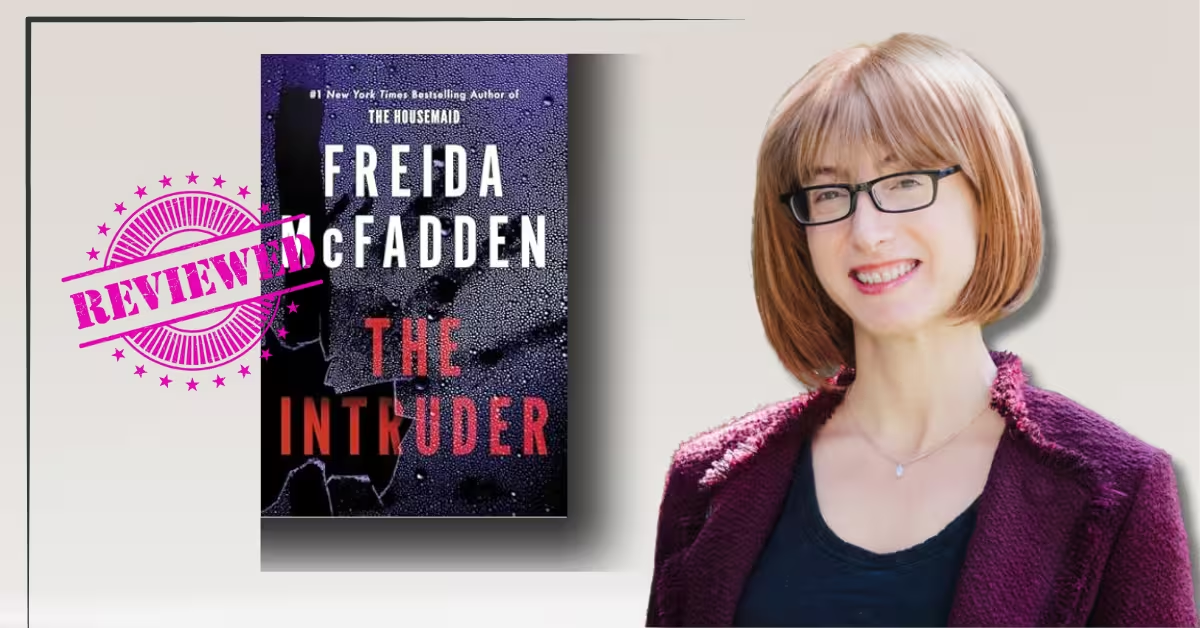

The Intruder by Freida McFadden (Poisoned Pen Press / Sourcebooks; October 7, 2025; audiobook by Dreamscape Media) blends storm-thriller urgency with domestic-psychological stakes, released in hardcover, ebook, and audio editions (narrated by Joe Hempel, Patricia Santomasso, and Tina Wolstencroft). Freida McFadden authors her latest The Tenant.

The novel opens with a teacher named Casey confronting a failing roof and a looming hurricane—“at least a fifty percent chance that… the roof… will collapse and kill me”—a line that doubles as the story’s thesis: random collapse can arrive at any time.

Soon after, the iconic image appears: a face at the window, as Casey sets cedar-scented candles, tapes her panes with duct tape, and tries to feel safe in isolation: “There’s a pale face staring at me from outside my window.”

2. Background

McFadden is a practicing physician specializing in brain injury and an international bestseller whose thrillers frequently top the charts; her official pages and recent retailer listings place The Intruder squarely in her mature psychological-thriller phase (and yes, it skyrocketed on Amazon/Audible at launch).

The author’s own site and the front-matter note emphasize accessibility: no graphic on-page gore or sex scenes; content warnings exist for readers’ mental-health safety and for parents monitoring teen readers.

3. The Intruder Summary

Casey, a former middle-school teacher living off the grid in a creaky cabin at the edge of the woods, is hunkering down for a violent storm when something—or someone—appears to be moving outside.

First, she thinks she sees a face at her bedroom window; she screams, and when she looks again, the face is gone. The moment is presented in stark, literal terms: “There’s a pale face staring at me from outside my window” (and then, “the face is gone”).

Trying to steady her nerves, Casey scans the yard and fixes on her toolshed. A light is shining inside—a physical impossibility, because there’s no power to the shed. “There’s a light shining outside. It’s coming from my shed,” she observes, realizing “somebody is inside. And they have a flashlight.”

With the landlines already failing in the storm, she can’t call her only nearby neighbor, Lee Traynor, and she can’t call the police either. She decides to check the shed herself, slipping her compact Glock 43X into her coat pocket—a gun her father taught her to use, because “a girl’s got to know how to shoot.”

The storm hurls the shed door off its hinges as Casey approaches. Inside, she finds a small lump under a blanket.

When she coaxes it to move, huge blue eyes and red hair appear: it’s a girl, pale, rail-thin, clutching a switchblade. “I’m not going to hurt you,” Casey says, lowering her guard because whoever’s in her shed is tiny, maybe twelve.

The girl gives her name as Eleanor “Nell” Kettering, though at first she’s evasive. It quickly becomes clear she’s a runaway in bad shape—undernourished, bruised, with circular scars that look like cigarette burns. Casey, who bears her own old burns and the trauma of an abusive mother, recognizes what she’s seeing. The storm forces Casey to bring Nell inside.

As the night worsens, Nell’s fear and volatility sharpen: she’s not just hiding in a shed; she’s arrived at Casey’s on purpose, and she’s brought a gun.

During the long, frightening night, two plot threads tighten. First, the storm knocks down a giant, precarious tree near Casey’s cabin. It’s been threatening to fall on the house, but in the chaos, the tree instead crashes onto the toolshed, flattening it—a vivid, near-miss that, in Casey’s words, shows a “universe in which [Nell] is lying dead beneath that giant tree.” Nell whispers to Casey, “You saved my life,” a fragile trust born of catastrophe.

Second, as the power fails and the wind howls, the girl’s story spills out in jagged pieces. She believes Casey’s neighbor Lee Traynor is her father, a man who “abandoned” her mother Jolene Kettering before Nell was born.

Nell has found Lee’s name and (forwarded) address and traveled across state lines to confront him. When day breaks, she forces Casey at gunpoint to take her to Lee’s cabin through the storm. There, she confronts him with the Glock raised: “You abandoned me and my mother. You left us. And now you’re going to pay.”

Lee is blindsided. He knows Jolene, yes—but he insists, shakily, that he never dated her. “I’m not your dad. I can’t be. It’s not possible,” he tells Nell, terrified but trying to stay rational as she aims the gun. He asks her name; she spits back “Eleanor Kettering… everyone calls me Nell.” The scene swells with dread before a different truth arrives: Lee’s brother—his hero—was involved with Jolene, and died twelve years earlier in a car crash. That timeline makes it plausible that Nell is Lee’s niece, not his daughter. Nell buckles as the truth dawns.

But the most dangerous revelation is still ahead. Shaking and sobbing, Nell blurts out what happened before she ran: her mother Jolene and Jolene’s boyfriend Jax had a vicious fight. Jax carries a switchblade and, in the chaos, Nell believes he stabbed her mother. Nell tried to help, got covered in blood, then fled in panic when Jax started accusing her (“They’re going to send you to jail!”). Casey calms her and promises—“I infinity promise, Nell”—to go to the police herself and make sure Nell is safe with family.

What Casey does instead is the book’s core moral swerve.

With phone lines down, Casey drives to Jolene’s basement apartment under cover of the storm, lets herself in with a key, and finds Jolene—alive, bleeding, clammy, drifting in and out of consciousness on the kitchen floor. Jolene has dark eyes and a beauty mark by her mouth, matching the eerie sketches in Nell’s notebook that Casey had mistaken for disturbing drawings of herself. Jolene sneers at questions, refuses to talk about her daughter, calls Nell “a bad apple. Bad to the core.”

The contempt curdles something in Casey that’s been smoldering since childhood.

Casey is not a paramedic; she pretends to be one. She takes a pack of cigarettes from Jolene’s purse and proposes a “game”: every time Jolene lies, Casey lights another cigarette—and must put the last one out. The implication is immediate and horrifying. When Jolene lies about the bruises and burns on Nell’s arms—“She probably did it to herself”—Casey presses the lit cigarette into Jolene’s skin. Jolene howls. On the next lie, Casey warns the burn will go on Jolene’s face.

Jolene finally whispers the truth: “I burned Nell a couple of times… she deserved it… these rotten kids—you have to teach them a lesson.” Casey wishes she’d said anything else. She doesn’t stop.

The narrative is careful here—McFadden doesn’t give a step-by-step blow-by-blow of Jolene’s final breaths. Instead, we watch Casey cross a line she’s crossed before. “Maybe I set my mother on fire,” she thinks later, a confession of vigilante violence, “and gave Jolene the same pain she dished out.”

When the power comes back and the news airs an update, Lee appears at Casey’s door with a taut face: the report says Jolene Kettering was killed “today”—not last night. Instantly, both of them understand what that timing implies. Casey didn’t go to the police. She went to Jolene—and finished the job.

Here’s the twist within the twist: Lee covers for Casey. Calmly, pointedly, he says that Casey was with him and Nell all afternoon. “How could you be in two places at the same time?” he asks, making it clear that if the police ever question it, he and Nell will say Casey never left.

Then he adds, in a quiet judgment that doubles as absolution, that anyone who could do what Jolene did to a little girl “doesn’t deserve to be alive.”

In the epilogue, six months later, the new family configuration has settled in: Lee is Nell’s legal guardian, and Nell has gained weight, begun to flourish, and is being homeschooled by Casey until she’s ready for a return to school.

Police never arrest Casey or Nell; Jax gets picked up—his shirt still had Jolene’s blood—and his rap sheet helps the case along, whether or not he “finished the job.” The novel ends in a low, throbbing key: Casey sits at Lee’s table teaching Nell poker, sharing toast, keeping promises.

The danger has subsided, but the moral ledger is permanently altered.

Key beats

- Storm night, isolated cabin: Casey sees a face at the window and then a light in the toolshed where no light should be. Phones are down; she arms herself and investigates.

- The intruder is a child: Casey discovers Nell, about twelve, filthy, starving, and armed with a switchblade; Casey brings her inside.

- Tree fall near-miss: The huge tree crashes onto the shed, narrowly avoiding the cabin and saving Nell’s life; a fragile bond forms.

- Confrontation at Lee’s: Nell believes Lee is her father and points Casey’s gun at him. He denies paternity and reveals Nell is likely his niece—his brother’s daughter; the brother died twelve years ago.

- Nell’s confession: She saw boyfriend Jax stab Jolene during a fight; she fled covered in blood while Jax pinned it on her. Casey “infinity promises” she’ll go to the police.

- Casey’s vigilantism: Instead of the police, Casey goes to Jolene’s apartment, finds her alive, and exacts brutal, cigarette-burn “justice,” forcing Jolene to admit abusing Nell.

- The timing reveal: News says Jolene died “today”. Lee alibis Casey, telling her “you couldn’t have gone,” and vows to back her if asked.

- Aftermath: Nell thrives with Lee; Jax is arrested; Casey and Lee—both damaged in different ways—create a protective world around the girl.

How the ending works

Literally, the ending hangs on timing and complicity. The storm night sets the fuse, but Jolene’s death certificate clock puts the fatal event on Day 2, not the frantic night Nell fled. That’s why Lee’s late-day doorstep conversation with Casey is so charged. His line—“We both agree… you couldn’t have gone”—isn’t a contradiction; it’s an alibi he is willing to share.

He knows what she did. He chooses to protect her because he’s seen what Jolene did to Nell (and, by implication, what was done to Casey once upon a time).

Thematically, McFadden frames vigilante justice as a corrosive echo of trauma. Casey’s past (she once “set [her] mother on fire”) mirrors the present; Jolene’s cruelty is punished with the exact tool she used on a child’s body—cigarettes.

The book’s title thus refers to the obvious stranger in the shed but also to something darker: the intruder is the rage that enters a life and never leaves, moving from one generation to the next unless someone intervenes. Casey intervenes—terribly, decisively.

And yet, the novel refuses to end on pure bleakness. The epilogue doesn’t offer naïve redemption; it offers stability. Nell has added fifteen pounds; she’s safe enough to learn poker and complain about homework. Casey and Lee are not saints, but together they create the safety net Nell never had.

4. The Intruder Analysis

4.1. The Intruder Characters

Casey (the “now” narrator) is brittle, funny, and resourceful—a self-isolated teacher whose routines (candles lined up, duct-taped windows, guns tucked in drawers) reveal both competence and wound. She loves “sleeping alone… making little sheet angels” and keeps others at arm’s length.

Eleanor (the “before” narrator, Ella) arrives trembling under a blanket with a switchblade, “about the size of a nine- or ten-year-old” but with eyes that signal a harder, older story. When the storm rips the toolshed open, Casey notices the teen is “covered in blood,” not obviously injured—a chilling, curiosity-hooking contradiction.

The father figure—first seen in memory—bequeaths Casey an “infinity promise,” a moral linchpin the story keeps testing: a promise “you can never break… On penalty of death from dysentery.” The absurdist punchline disarms as it deepens trust.

Relationships pivot on who gets believed: Casey wants to shelter, but her intruder’s drawings—page after page of a woman tortured—threaten the fragile bond: “The woman in these drawings is me.” And as Casey realizes, she left her gun “at the bottom of my dresser drawer. In the bedroom. Where Eleanor is sleeping.”

Eleanor’s “before” chapters render hunger, school discipline, and shaky adult systems with a withering, funny teen voice (“principal’s-office hell”), making her motives feel painfully real long before the twist lands.

Together, their dynamic asks a hard question: when survival becomes an ethic, how far will you go—and who gets hurt when you do?

4.2. The Intruder Themes and Symbolism

Isolation vs. intrusion. The cabin is both a refuge and a trap. Candles, taped glass, and the dead phone lines create a ritual of safety that fails the moment an outside gaze appears.

Promises & authority. The “infinity promise” motif becomes a counter-religion, a code that trumps institutions. Casey extends it to Eleanor—“I won’t tell anyone… if you don’t give me permission”—and instantly gains a sliver of trust.

Justice vs. revenge. Memories with her father muddy the waters: “When someone deserves bad things… it’s sometimes up to you to dispense justice.” The line haunts every choice Casey makes.

Storm as psyche. The hurricane mirrors panic spikes—faces at windows, lights flaring in the shed (“There’s a light shining… from my shed”), and a world where even movement outside reads as threat.

Storytelling as control. Eleanor’s bedtime story weaponizes narrative itself: Cassie’s limbs feed a fire; promises are “lies”; keeping secrets equals safety. It’s a miniature of the book’s core power struggle.

5. Evaluation

1) Strengths / positive reading experience

The Intruder is pure propulsion. Short cliffhanger chapters, alternating timelines, and concrete, cinematic set-pieces (the window scare; the flashlight widening the shed’s darkness; the blood-streaked hoodie) make this a one-sitting read. The prose lands fast and clean, often slyly funny even when it’s grim—e.g., duct-tape “fix anything” optimism, or an “axe-wielding giant” fantasy that collapses into a real flashlight in the shed. ;

2) Weaknesses / what may not work for you

Some readers may want more atmospheric lingering or deeper subplots beyond the central promise-and-power engine; if you go in seeking Sharp Objects-level literary density, you’ll find a more streamlined, commercial ride. External reviews also flag its momentum-first design as the feature, not the bug.

3) Impact (emotional & intellectual)

I finished with my shoulders tight, my empathy tugged both ways. The “infinity promise” isn’t cute—it’s a survival hack, and watching it bend (and maybe break) under pressure creates real moral static.

4) Comparison with similar works

If you loved isolated-setting dread like The Cabin at the End of the World or intergenerational trauma angles akin to Sharp Objects, this sits in that crosswind while staying squarely McFadden—fast, twisty, and talk-about-it-at-work tomorrow.

6. Personal Insight

Trauma-informed classrooms routinely wrestle with the novel’s central dilemma: how to build trust with students who’ve been failed by adults. Casey’s “infinity promise” is a narrative version of predictable care—a known practice in education that emphasizes consistent follow-through and student agency. The book’s Author’s Note, which points to content warnings on the writer’s website, aligns with current best practices around reader- (and student-) centered consent.

For context on how McFadden’s wider cultural moment intersects with audiences hungry for twisty, high-concept stories, see recent coverage of her movie news (The Housemaid) and journalism on her dual career (physician/author) and 17M+ sales footprint; together they explain why The Intruder was pre-positioned to trend.

Educators can also pair The Intruder with data-rich discussion on child welfare outcomes and the importance of stable, trustworthy adult relationships—where the “infinity promise” functions as a narrative case study in why predictability saves lives (external policy links for current stats will vary by region; consider your local child services dashboards and national education reports).

7. The Intruder Quotes

“There’s a pale face staring at me from outside my window.”

“It’s a girl. And she’s holding a knife.”

“An infinity promise… is a promise that you can never break… On penalty of death from dysentery.”

“The woman in these drawings is me.”

“When someone deserves bad things… it’s sometimes up to you to dispense justice.”

8. Conclusion

The Intruder is a lean, white-knuckle psychological thriller that uses a storm and a promise to pry open questions about trust, justice, and how we carry childhood forward into adulthood. The effect is immediate and memorable: images you can’t unsee, a promise you can’t easily forgive, and a final turn that reframes who’s protecting whom.

Recommended for readers who love Freida McFadden’s brand of twisty, emotionally legible suspense; fans of cabin-set thrillers; and book clubs eager to debate “what would you do?” scenarios. If you prefer slow-burn literary mood pieces or procedural puzzles with granular forensics, this isn’t that book—but as a page-turning, conversation-starting thriller, it’s one of McFadden’s most teachable and discussable novels to date.