I still think The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is the rare thriller that doesn’t just entertain you—it interrogates you.

If you’ve ever wondered how a democracy can be shaken by fear, propaganda, and a single well-placed lie, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) has an answer that’s as elegant as it is cruel. Directed by John Frankenheimer, written by George Axelrod, and adapted from Richard Condon’s 1959 novel, it’s a Cold War political thriller that plays like a nightmare with perfect grammar.

It was released on October 24, 1962, right in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which gives the film an extra pulse of dread you can almost feel in your teeth. The story’s core idea—mind control as a political weapon—still lands because it isn’t really about gadgets or hypnosis so much as it’s about vulnerability.

I’m also writing about The Manchurian Candidate (1962) here because it belongs in that rare company of films that feel essential rather than merely “classic.”

My overall impression is simple: this is a film that turns paranoia into art without romanticising it.

Background

The Manchurian Candidate (1962) arrived when Cold War anxiety wasn’t an atmosphere—it was a daily weather system.

John Frankenheimer directed and produced The Manchurian Candidate (1962), with George Axelrod adapting Richard Condon’s novel into a screenplay that moves like a blade.

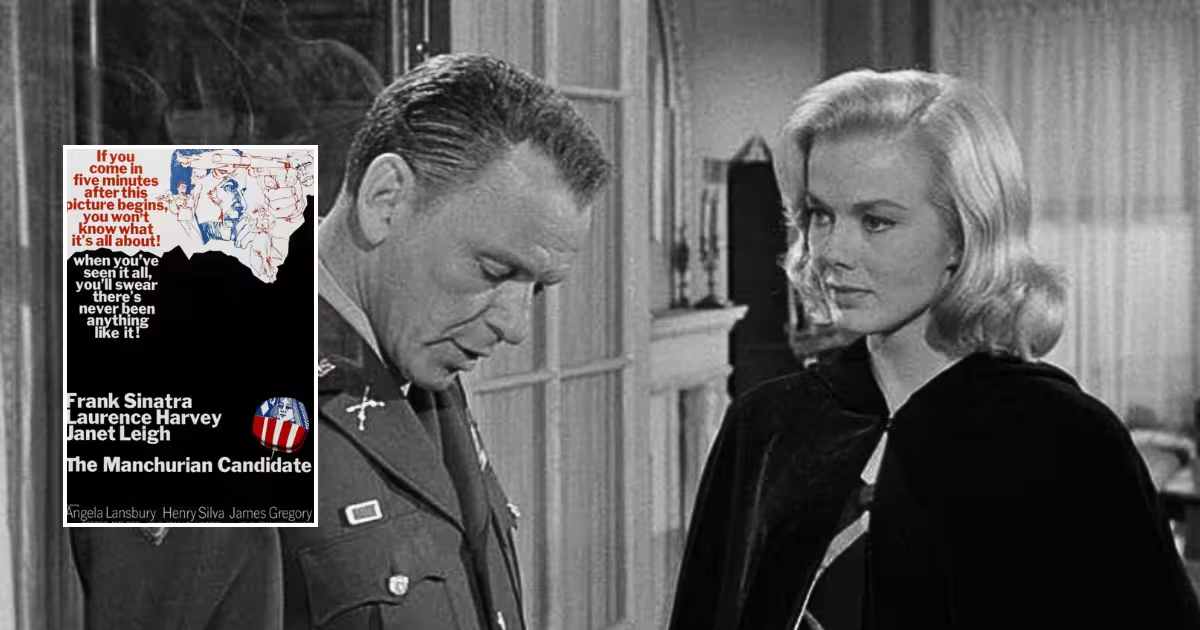

The film is shot in stark black-and-white and runs 126 minutes, which sounds tidy on paper but feels emotionally longer in the best way. The cast is stacked: Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey, Janet Leigh, and an unforgettable Angela Lansbury.

What makes The Manchurian Candidate (1962) sting is that it borrows the texture of real fear: the era’s fixation on “brainwashing” and the suspicion that enemies could rewrite the self. That anxiety didn’t stay in fiction—later, the CIA itself acknowledged that historians have argued a “Manchurian Candidate”–style goal was associated with MK-ULTRA and related projects.

The film’s political satire also leans into the logic of McCarthyism, where accusation becomes a career and hysteria becomes policy.

In other words, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) isn’t just “about communists”—it’s about how quickly a society can be trained to accept cruelty if you wrap it in patriotism.

Behind the scenes, the movie has its own strange aura of obsession and precision: it was filmed in places like New York City, including landmark locations that make the conspiracy feel uncomfortably domestic.

It’s also packed with production lore—like the fact that nearly half of the film’s $2.2 million budget reportedly went to Sinatra’s salary, which is both a star-system detail and a reminder of how power concentrates. For me, these details matter because they underline the film’s central irony: even a story about manipulation is still shaped by money and influence.

The film’s famous “out-of-focus” choice in a key deprogramming moment is another example—what could be a mistake becomes a subjective weapon, making us inhabit distortion rather than merely observe it.

Critically, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) became more than a hit thriller: it earned major awards attention, including Oscar nominations (notably for Lansbury) and other honours. And in 1994, it was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry, a formal way of saying: this film is part of the cultural record, whether we’re comfortable with it or not.

With that context in mind, here’s the full spoiler-filled plot of The Manchurian Candidate (1962).

The Manchurian Candidate Plot

During the Korean War, an American platoon disappears into enemy hands and returns looking whole, which is the first lie the film asks you to swallow.

Captain Bennett Marco comes back with a Medal-of-Honor narrative already written in his mouth, and Sergeant Raymond Shaw comes back wearing heroism like a borrowed coat.

The men speak about Shaw in identical, glowing phrases, as if their memories have been stamped from the same metal. Marco accepts the story at first because soldiers are trained to accept stories that keep the unit from falling apart.

But the praise feels too smooth, and Shaw himself feels like a locked room.

Shaw is, in truth, prickly and cold, and his fellow soldiers don’t seem to like him at all when they aren’t reciting the official version of him. The film quietly lets you notice this contradiction before it explains it, which makes the revelation feel like something you discovered rather than something you were told.

When Shaw returns to his powerful political household, his mother Eleanor Iselin treats his hero status like currency that can be spent at the right moment.

His stepfather, Senator John Iselin, rides a wave of loud accusations and shaky facts, and it is immediately clear that this family’s love language is leverage.

Marco, now in Army Intelligence, begins having a recurring nightmare that feels less like fantasy and more like a replay. In the dream, the platoon is gathered as an audience while communist officials demonstrate their mastery over the human mind. Shaw, calm and blank, kills on command as if violence has become a simple administrative task.

Marco wakes up not relieved but contaminated, like he has carried something back across the border that no shower can remove.

The nightmare follows Marco into daylight, and the film makes this bleed between sleep and waking feel like a moral problem rather than a supernatural one.

He tries to ignore it, because ignoring it is easier than believing it, but the images keep returning with the stubbornness of trauma. The more he fights the dream, the more the dream starts to feel like evidence.

Eventually he learns that another soldier, Allen Melvin, is haunted by the same vision, and their shared details make the impossible suddenly procedural.

The story then starts behaving like a conspiracy not because someone says “conspiracy,” but because patterns appear where there should be randomness. Marco notices how the men respond when asked about Shaw, and he can’t shake the sense that he’s listening to a recording rather than a memory.

He tests assumptions, follows hunches, and keeps running into the same wall: the war years are missing, and the missingness has shape. Meanwhile Shaw, desperate to wound his mother in the only way he can, takes a job at a newspaper run by Holborn Gaines, a fierce critic of Iselin’s political theatre.

That choice should be an act of independence, but in this film independence is often just another string you don’t yet see.

Not long after, Shaw is quietly nudged into proving that he can still be used. He is triggered through a banal ritual—card play, small talk, a social setting—and the film’s genius is how it makes activation feel like an ordinary slip in routine.

When Shaw is “on,” he becomes a mechanism, and when he is “off,” he becomes a man again, but the man has no memory of what the mechanism did. Shaw murders Gaines with a horrifying efficiency that is almost polite, and then returns to himself as if waking from a nap, his face blank with the tragedy of not knowing what he has become.

A North Korean agent named Chunjin arrives at Shaw’s apartment under the mask of service, offering himself as help while actually functioning as a handler and gatekeeper.

Shaw, unsuspecting, hires him as valet and cook, as if evil always comes dressed as convenience. When Marco later visits, he recognises Chunjin from the captivity period that his mind cannot quite access, and recognition turns him feral.

He attacks Chunjin and tries to force answers out of him, but the scene only proves how helpless brute force is against a system built on secrecy.

Marco is arrested, and this is where the film introduces Eugenie “Rosie” Cheyney in a way that feels simultaneously romantic and suspicious. She meets him on a train, speaks with odd intimacy, and then appears again to bail him out, as if the universe has assigned him a companion.

Their connection blooms fast, which in another film would be sentimental, but here speed feels like another form of programming. Still, Marco clings to Rosie because paranoia is lonely, and love—even imperfect love—can be a temporary shelter.

As Marco pushes the Army to investigate, he and Melvin begin identifying faces and symbols that surfaced in their nightmares, and those matches make the case impossible to dismiss.

The film turns memory into a dossier: photographs become corroboration, and shared trauma becomes a map. Marco’s superiors, once sceptical, begin to take him seriously not because they believe in mind control, but because they believe in patterns. And once institutions start believing in patterns, they start believing in plots.

Shaw, meanwhile, stumbles into something that looks like genuine tenderness: he reconnects with Jocelyn Jordan, the daughter of Senator Thomas Jordan, a political opponent of the Iselins.

Their romance has a softness the rest of the film denies itself, as if to show that a person can still reach for love even while being used as a weapon. Eleanor, however, sees Jocelyn less as a woman and more as a strategic doorway to her father’s influence.

She tries to bend Senator Jordan toward supporting Iselin’s vice-presidential ambitions, but Jordan refuses, and refusal in this story is treated like a crime.

Eleanor’s rage is not merely political; it’s possessive, the rage of someone who sees other human beings as her instruments and cannot tolerate a broken tool. She sends Shaw to kill Senator Jordan, and the act is framed not as a personal vendetta but as a move on a chessboard.

The tragedy intensifies when Jocelyn unexpectedly witnesses the murder, and Shaw kills her too, not out of hatred, but out of the cold necessity of completing the assignment. When Shaw returns to himself and learns what happened, his grief is devastating precisely because it is sincere and also useless.

At this point, Marco begins to understand the mechanics of Shaw’s conditioning with the clarity of someone staring at a loaded gun. The trigger is bound to a specific card—an image that turns a human being into a command-response device—and the simplicity of it is almost insulting.

Marco forces a confrontation, using a deck as a tool, pushing Shaw toward awareness, attempting to deprogram him not with kindness but with urgency.

The scene feels like a moral wrestling match: can you save someone by hurting them, and if you can, what does “save” even mean afterward?

Shaw begins to awaken to the outline of his own captivity, and the film’s cruelty is that awakening does not bring peace—it brings horror. He learns that his heroic memory is a planted story, a medal pinned to a fabrication, and that his “bravery” has been used to disguise his enslavement.

Marco, now fully committed, tries to discover the next assignment before it happens, because in conspiracies timing is everything and “too late” is the default outcome.

As Marco races the clock, Eleanor calmly prepares the final act, treating assassination as an elegant solution to a political bottleneck.

The plan is audacious in the way only political nightmares are audacious: during the party convention, Shaw will assassinate the presidential nominee, allowing Iselin, positioned as the vice-presidential nominee, to rise by default.

In the chaos, emergency powers will be demanded, and democratic norms will be replaced by authoritarian control wearing a legal mask. What chills me is how the film doesn’t frame this as far-fetched; it frames it as depressingly plausible, because it relies less on magic and more on opportunism.

In this world, the coup is not a sudden military takeover—it’s a procedural exploit.

On the convention night, Shaw moves like a shadow through the massive civic theatre of Madison Square Garden, disguised in a costume that lets him pass as harmless.

He climbs into a sniper position high above the floor, a literal elevation that mirrors the plot’s cold detachment from ordinary life. Marco and his allies rush to stop him, but the film keeps the tension tight by making “stop him” feel like trying to stop an idea after it has already been spoken.

The convention, all banners and cheers, becomes a ritual space where patriotism and manipulation blur.

Then the film delivers its final twist with a grim kind of dignity. Shaw, confronted with the full truth of what has been done to him and what he is about to do, aims away from the intended victim.

Instead, he turns the rifle toward the people who made him, toward Eleanor and Iselin, the domestic architects of his nightmare. The act is not triumphant; it’s tragic, because it is the only agency left to him, and it arrives dressed as murder.

Marco bursts into the booth too late to offer rescue, which feels like the film’s thesis about institutions and timing. Shaw, wearing the Medal of Honor that now feels like an emblem of stolen identity, speaks as if he is finally fully present in his own body. He has stopped the plot, but he cannot stop the fact that he was the plot’s instrument.

And so he completes the last act of control by removing himself from the board entirely, leaving Marco to carry not only survival but guilt.

Afterward, the film doesn’t give you a clean exhale. Marco, with Rosie, mourns Shaw’s death, and the mourning is complicated because it contains anger, pity, and helplessness in equal measure. The conspiracy has been disrupted, but the damage is not reversible, and the characters do not get their innocence back as a reward.

What lingers is the sense that manipulation thrives not only in foreign enemies but in familiar rooms, and that political language can become a hypnotist’s swing. The Manchurian Candidate (1962) ends as it began: with the feeling that the most terrifying battlefield is the mind.

Cast:

- Frank Sinatra as Major Bennett Marco – the troubled Korean War veteran whose recurring nightmares lead him to uncover the chilling brainwashing conspiracy.

- Laurence Harvey as Raymond Shaw – the seemingly heroic soldier turned unwitting assassin, manipulated through psychological programming.

- Angela Lansbury as Eleanor Shaw Iselin – the cold, power-hungry mother and mastermind whose ambition fuels the sinister political plot.

- Janet Leigh as Eugenie Rose Cheyney – Marco’s love interest and compassionate ally in his fight to expose the truth.

- James Gregory as Senator John Yerkes Iselin – Eleanor’s equally ambitious husband and politician whose rise is essential to the conspiracy.

- Henry Silva as Chunjin – a communist agent whose presence deepens Marco’s suspicions and reveals the extent of the plot.

- Leslie Parrish as Jocelyn Jordan – the daughter of a liberal senator whose tragic involvement underscores Shaw’s loss of agency.

- John McGiver as Senator Thomas Jordan – a political opponent whose stance challenges the Iselin agenda, and more.

The Manchurian Candidate Analysis

The moment I finished revisiting The Manchurian Candidate (1962), I realised the real aftershock is not the twist but how calmly the film makes panic feel normal.

Direction and cinematography: John Frankenheimer shoots The Manchurian Candidate (1962) like a nightmare you cannot shake off, with scenes that glide from ordinary spaces into psychological traps.

The famous decision to keep Marco slightly out of focus in the deprogramming scene was Frankenheimer choosing feeling over neatness, and it lands because it mimics distortion rather than “style.”

When the film pivots between public spectacle and private dread, the camera behaves like a witness who knows more than it should.

Acting performances: Frank Sinatra gives Bennett Marco a tight, jittery intelligence that makes his obsession feel like duty rather than melodrama, while Laurence Harvey plays Raymond Shaw as a man whose emotions have been filed down into weapon parts.

Angela Lansbury is the thunderclap, and even Britannica calls out how noteworthy her work is, including the fact that it earned an Academy Award nomination for supporting actress.

Script and dialogue: George Axelrod’s writing gives The Manchurian Candidate (1962) its razor edge, because the satire never breaks the suspense and the suspense never forgets the joke.

Music and sound design: David Amram’s score supports the film’s unsettled mood without trying to “tell” you what to feel, which is exactly why the tension creeps up rather than announces itself.

Themes and messages: At heart, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is about control, not only political control but the terrifying possibility that your own mind could become occupied territory.

The plot deliberately mixes Cold War nightmares with domestic ambition, turning a mother into a handler and a decorated soldier into “the mechanism.” Scholars cited in the film’s critical discussion argue that its deepest worry is “embattled human autonomy,” which still feels like the most honest way to describe the film’s ache.

The detail that it was released on October 24, 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis, makes the movie feel less like entertainment and more like a cultural symptom.

Even the political theatre inside the story—grandstanding, fear-mongering, manufactured enemies—lands as an argument that paranoia is not just a mood but a tool.

Comparison: If you love political thrillers, you can draw a straight emotional line from The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to later conspiracy-driven spy stories, where the scariest enemy is often inside the system rather than outside it. What sets The Manchurian Candidate (1962) apart is its willingness to be funny and horrifying in the same breath, like it knows propaganda can smirk while it lies.

Audience appeal / reception: The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is ideal for cinephiles, Cold War history nerds, and anyone who enjoys political thrillers that refuse to play safe, and it still scores 97% on Rotten Tomatoes (67 reviews, average 8.8/10) and 94/100 on Metacritic (20 critics).

What I keep thinking about, though, is how The Manchurian Candidate (1962) makes manipulation feel intimate rather than abstract.

Personal Insight and Lessons

Today we talk about influence as if it is always obvious, like a bad advertisement you can skip, but the film insists influence works best when it pretends to be love, duty, or patriotism.

That is why Mrs Iselin is so chilling, because she does not merely push ideology, she rewires family, turning closeness into a delivery system for commands. And that is why Marco’s panic is moving, because he is fighting a battle he cannot fully explain without sounding insane.

In 2025, the “brainwashing” idea can sound melodramatic until you notice how easily people can be nudged into certainty, especially when fear is the currency of the day. The film’s nightmare logic still mirrors how modern misinformation works, because repetition and emotional triggers can create a reality that feels more solid than facts.

I also cannot ignore the timing, because releasing The Manchurian Candidate (1962) during the Cuban missile crisis makes it feel like a message in a bottle thrown into a storm.

So the lesson I take is not “everyone is programmable,” but “systems will always try,” because it is cheaper to steer people than to persuade them.

The film hurts because it shows how a person can be praised as a hero in public while being hollowed out in private, and the distance between those two selves is where authoritarian fantasies thrive.

On a more personal note, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) makes me think about how often we confuse intensity for truth and loyalty for clarity. It pushes me to ask a boring but necessary question: “Who benefits from the version of the story I am about to repeat.”

If nothing else, The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is a reminder that freedom of will is not a slogan, it is a practice you have to defend every day.

Awards and honours

The Manchurian Candidate (1962) was nominated for the Academy Awards for Supporting Actress (Angela Lansbury) and Film Editing (Ferris Webster).

Lansbury also won the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress, and the film later entered the United States National Film Registry in 1994. It is also ranked #17 on AFI’s 100 Years…100 Thrills list, which feels exactly right for a movie that tightens its grip the longer you sit with it.

And yes, I’m saying this plainly for probinism.com readers: The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is already on your own “101 Best Films You Need To See” list, sitting at #39, which makes it one of your 101 must-watch films by definition.

The Manchurian Candidate Quotes

- “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.”

— Repeated by brainwashed soldiers (e.g., Major Bennett Marco and Corporal Melvin) about Raymond Shaw, ironically highlighting his unlikability while revealing the depth of Communist brainwashing that implants false heroism and memories. - “Why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitaire?”

— The trigger phrase used by handlers (including Mrs. Iselin and others) to activate Raymond’s brainwashed state, leading him to reveal the Queen of Diamonds card and become obedient for programming or assassination orders. - “His brain has not only been washed, as they say… it’s been dry-cleaned.”

— Dr. Yen Lo (during the brainwashing demonstration to Soviet/Chinese officials), boasting about the thoroughness of the conditioning that turns Raymond into a perfect, guilt-free assassin with no memory of his actions. - “It’s a terrible thing to hate your mother. But I didn’t always hate her. When I was a child, I only kind of disliked her.”

— Raymond Shaw (to Marco), underscoring his deep-seated resentment toward his manipulative mother, Eleanor Iselin, who is revealed as his American handler orchestrating the Communist plot. - “Made to commit acts too unspeakable to be cited here by an enemy who had captured his mind and his soul. He freed himself at last and in the end, heroically and unhesitatingly gave his life to save his country. Raymond Shaw… Hell. Hell.”

— Major Bennett Marco (reading his prepared Medal of Honor citation for Raymond, then breaking down), reflecting the tragic irony as Raymond ultimately turns against his programming to assassinate his mother and stepfather instead of the intended target, committing suicide in the process. - “Intelligence officer. Stupidity officer is more like it. Pentagon wants to open a Stupidity Division, they know who they can get to lead it.”

— Major Bennett Marco (self-deprecatingly about Senator Iselin), satirizing the McCarthy-like demagogue whose accusations are exploited by his wife in the conspiracy. - “There are two kinds of people in this world: Those that enter a room and turn the television set on, and those that enter a room and turn the television set off.”

— Raymond Shaw, capturing his aloof, cynical personality amid the political satire. - “Political murder in this country has never been anything more than a means to an end… unless it was the fruit of a diseased brain. Assassination has always been the tool of the zealot, never the successful politician.”

— Said by a political operative early in the film. This line sets up the film’s central twist: the conspirators are not zealots, but cold, calculating politicians (and their fo

Pros and cons

I think The Manchurian Candidate (1962) is one of the sharpest political thriller films ever made, because it uses suspense to sneak philosophy into your ribs. It is also still emotionally readable, because the central tragedy is human before it is ideological.

Pros: • Stunning visuals • Gripping performances • Biting satire that never kills the tension

Cons: • Slow pacing in parts • Some plot mechanics feel deliberately dreamlike rather than “realistic.” My recommendation is simple: a must-watch for thriller enthusiasts, and honestly essential viewing for anyone trying to understand how fear can be engineered into politics.

Conclusion

The Manchurian Candidate (1962) lands as a cold, unnerving warning about how power can hijack both politics and the human mind. By the end, Raymond Shaw—engineered into an assassination tool—briefly reclaims agency in the only way left to him: he turns his weapon against the true architects of his control, disrupting the conspiracy but at a devastating personal cost.

The film closes with a bitter aftertaste: even when one plot is stopped, the systems that enable manipulation—fear, propaganda, ambition, and blind loyalty—remain dangerously intact.

Recommendation

If you’re drawn to tense political thrillers with psychological edge, this is essential viewing—especially because its final act doesn’t offer comfort, only consequence. Watch it for its sharp satire, escalating paranoia, and the way it exposes how “patriotism” can be weaponized.

Recommended pairing: follow it with a short read on Cold War-era red-scare politics and media demagoguery to fully appreciate how the film’s ending isn’t just tragedy—it’s a diagnosis.