We crave a blueprint for getting home—after war, after loss, after bad decisions—and The Odyssey gives one, showing how cunning, hospitality, and memory rebuild a life.

It is An ancient Greek epic in 24 books, attributed to Homer, the Odyssey follows Odysseus’s ten-year struggle to get home to Ithaca after Troy—while his wife Penelope and son Telemachus fend off predatory suitors—staging core themes of nostos (homecoming), xenia (hospitality), testing, and omens.

Homer’s epic says that the long way back—navigating monsters, politics, and one’s own ego—is the work of becoming fully human.

Composed in 24 books and 12,109 lines of dactylic hexameter, the poem is an orally rooted, non-linear narrative whose core patterns (nostos, xenia, testing) have been mapped by classicists and traced across cultures for nearly three millennia.

The Odyssey is best for curious readers who like myth with moral ambiguity, teachers seeking durable themes, and creators mining archetypes; not for those wanting a straight war yarn (that’s the Iliad), or a geography you can GPS.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Homer’s Odyssey (8th–7th c. BCE) survives as one of antiquity’s foundational epics, likely shaped for oral performance and later divided into the familiar 24 “books.”

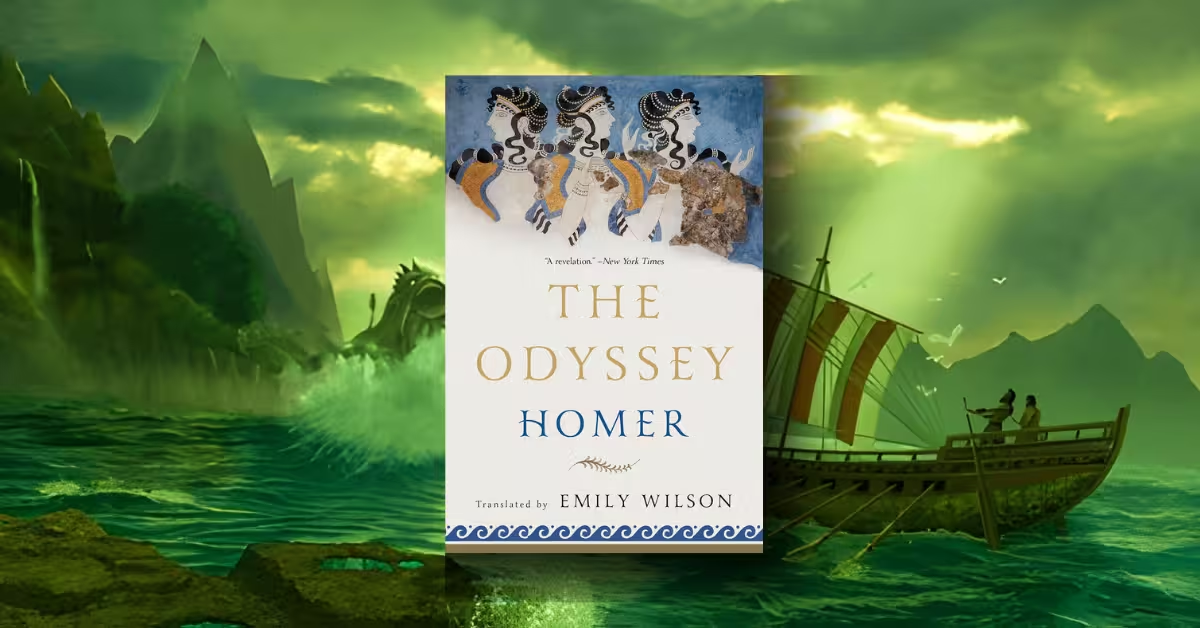

Its modern readers commonly meet the poem through acclaimed English versions by Richmond Lattimore, Robert Fagles, and, recently, Emily Wilson—the first woman to publish a complete English translation—whose introduction frames xenia (guest-friendship) and moral complexity in plain, bracing prose.

The epic opens in medias res1, with Telemachus2 in Ithaca3, then veers to Odysseus4’ wreck and rescue by Phaeacians5, and finally loops back through his own storytelling (Books 9–12) before the homecoming and reckoning.

And, because the poem speaks mainly in speeches—characters narrate, test, and answer—its “voice” feels uncannily alive in translation, a reason it continues to anchor the Western canon and today’s search engines alike.

The poem’s length and meter are empirical: 12,109 hexameter lines; its themes—homecoming (nostos), hospitality (xenia), testing, and omens—are the analytic backbone cited across scholarship and handbooks.

Finally, as BBC Culture’s global poll of critics and writers ranked it the most enduring story, the Odyssey remains a “living” classic in public imagination.

2. Background

Homeric poetry emerged from an oral performance ecology where rhapsodes improvised within formulaic patterns; writing followed later, and the epic’s “book” divisions are post-composition.

Historically, the poem reflects the early Greek world: elite gift-exchange, sea travel, and fragile institutions after the Mycenaean collapse; Britannica’s overview tracks this long arc from the “Dark Age” to Classical antiquity.

Scholars now read the voyage metaphorically more than cartographically; mapping the Cyclopes, Scylla, or Thrinacia tends to miss the poem’s psychological geography.

Context clarifies why the poem obsesses over recognition, reciprocity, and restraint.

Moreover, Emily Wilson’s introduction shows how xenia functions as diplomacy and domination at once—hospitality as a networking tool and a pretext for exploitation.

That doubleness keeps the Odyssey modern: every harbor is a test of ethics.

And yes, the numbers matter for search intent: 12,109 lines, 24 books, an action span of roughly six weeks (though Odysseus wanders ten years)—figures that recur in encyclopedias and classrooms.

3. The Odyssey Summary

Book 1 — The Boy and the Goddess

Athena sets the story in motion while the poet asks, “Tell me about a complicated man.”

On Olympus, the gods debate Odysseus’ fate, and Zeus6 agrees that Hermes7 will order Calypso8 to let him go. Athena then sails for Ithaca disguised as Mentor to spur Telemachus into action. The notes summarize this divine kickoff succinctly: she “inspires Telemachus… Then she flies away, like a bird.”

In Ithaca, Athena meets the shy prince, steels his courage, and departs—“the owl-eyed goddess / flew away like a bird, up through the smoke,” leaving him “braver, more determined.” Telemachus turns from wonder to duty and walks to face the suitors in his father’s hall.

Inside, the suitors feast and listen to Phemius9 singing of the Greeks’ bitter returns from Troy.

Penelope10, shattered by the song, begs the bard to change it: “Stop this upsetting song… I miss him all the time—that man, my husband.”

Telemachus, suddenly authoritative, defends the poet and draws a line between household and public voice: “Poets are not to blame… Go in and do your work… It is for men / to talk, especially me. I am the master.” He then issues his first command to the suitors11: “At dawn, let us assemble in the square… You have to leave my halls. Go dine elsewhere!” The moment marks his step into adult responsibility—and foreshadows a reckoning sanctioned “by Zeus.”

Their reaction is scornful; Antinous12 sneers that the gods have taught the boy to boast, and Eurymachus13 probes the identity of the mysterious guest. Telemachus holds his ground and asserts at least the right to rule “my own house.”

Thus Book 1 closes with a house still usurped but a prince beginning to act like a king.

In plain terms: the epic opens with a prayer to the Muse14, a divine plan to free Odysseus, and Athena’s first intervention in Ithaca to awaken Telemachus’ courage; at home, the suitors’ lawless banqueting collides with Penelope’s grief and the boy’s new resolve, setting up the assembly—and the long struggle to reclaim the house—at dawn.

Book 2 — A Dangerous Journey

Telemachus convenes Ithaca’s first assembly since Odysseus left, begging the elders to stop the ruin the suitors bring to his house.

The crowd first pities the boy, but Antinous flips the blame to Penelope, revealing her famous delaying ruse with the shroud: by day she wove, “and then at night… she unwove it,” until a slave exposed the trick. Eurymachus snarls that they are not afraid of “this boy” or “pointless portents,” and Telemachus, undeterred, asks simply for a ship and twenty men to seek news of his father. The hall murmurs as Mentor defends just rule and rebukes the townsmen for letting a handful of suitors devour a king’s estate.

Zeus sends an omen: two eagles “wheeled and whirred… with eyes like death,” which Halitherses15 reads as a sign Odysseus is near and doom is coming for the suitors. Eurymachus mocks the prophecy and the meeting breaks up.

Leocritus jeers that even if Odysseus returned alone, he would die trying to fight them.

So the assembly dissolves, and the suitors return to feast in Odysseus’ hall.

On the beach, Telemachus prays, and Athena (as Mentor) answers with a plan: “You will be brave and thoughtful… I will equip a good swift ship for you.” Back home, his old nurse Eurycleia quietly draws wine and barley, swearing not to tell Penelope for twelve days. Meanwhile Athena borrows Noëmon16’s ship, drags it to the water, gathers a crew, and pours sleep over the “drunken suitors,” cups falling from their hands. At her call, Telemachus slips from the house to the waiting vessel. A clean west wind, “pure Zephyr,” fills the bright sail; they pour libations to the gods and slide into the night.

Book 2 thus turns Telemachus from a silenced son into a voyager, giving him purpose and allies.

The suitors’ swagger and the public’s apathy set the stakes for the reckoning to come.

Most of all, the chapter balances mortal initiative with divine nudges: Telemachus speaks, plans, and rows, but Athena opens every door, from ship to wind. And as the omen of eagles promises, the journey he starts tonight is the beginning of the suitors’ end.

Book 3 — An Old King Remembers

Telemachus lands at Pylos17 at dawn, where crowds sacrifice “black bulls for blue Poseidon18,” and he steps into a world of ritual and hospitality.

Athena, masked as Mentor, steels him—“Do not be shy, Telemachus”—and marches him straight to old King Nestor19. The Pylians greet the strangers at the spits, seat them on fleeces, and share the feast before questions, modeling sacred guest-right. Athena promises the boy he will “work out what to do, / through your own wits and with divine assistance.”

Once they eat, Nestor listens as Telemachus asks for news of his father, and the old king remembers the bitter homeward split after Troy. He recounts Athena’s wrath at Greek sacrilege and the fates of the leaders—Agamemnon20 murdered by Aegisthus, the love of his wife Clytemnestra, Menelaus21 blown to Egypt, while Nestor reached home.

Nestor warns the boy to remember the tale of Aegisthus22 and be wary.

He urges a next step: go on to Sparta and ask Menelaus.

First, however, there is more feasting and prayer. Nestor sacrifices a heifer, the thigh-bones are burned “with double fat,” and the youths taste the entrails—piety punctuating counsel. Athena’s parting sign comes spectacularly; when the moment is secure, she reveals herself and “flew away, transformed / into an ossifrage,” leaving the Pylians awed and certain the mission is blessed. At dawn Nestor outfits Telemachus like a true guest: bath, cloak, a place of honor, then a chariot, provisions, and his youngest son Pisistratus to guide him onward. The pair drive hard across the plain, overnight at Pherae, and press on toward Sparta as Book 4 begins.

The episode shows Telemachus learning how heroes travel: ask plainly, honor the gods, eat, bathe, and accept pompe—proper “sending” to the next host.

It also defines Athena’s mentorship: courage first, then a sign that makes human courage feel divinely backed.

Thus Book 3 is a bridge—from a shy prince to a capable traveler, from Ithaca’s insult to the wider network of Greek memory and help.

Book 4 — What the Sea God Said

Telemachus and Pisistratus reach Sparta and are swept into Menelaus’ glittering double-wedding feast and flawless hospitality.

Menelaus rebukes any hesitation about welcoming strangers and orders the guests bathed, anointed, and seated at a laden table. Helen soon recognizes Telemachus; after tears rise, she slips pharmakon23, a “magical drug” into the wine that “removes all capacity for grief.” They trade Troy tales: Helen recalls Odysseus’ disguise in the city, and Menelaus praises his iron self-control inside the Wooden Horse.

At dawn, Menelaus tells how storms drove him to Egypt, where he captured Proteus, the “old sea god,” to learn the fates: Agamemnon murdered, Ajax drowned, Odysseus detained. Proteus’ news strikes home: “Calypso has him trapped upon her island… he has no fleet or crew.”

Menelaus offers lavish gifts to speed the young prince onward.

Meanwhile in Ithaca, the suitors discover the voyage, plot an ambush, and Penelope is crushed with fresh grief.

Night falls in Sparta and then “rosy-fingered Dawn” breaks; Menelaus strides out “like a god” and asks why Telemachus has crossed the sea. The boy answers plainly: the suitors “eat my house,” slaughtering sheep and cattle, and he begs for truth, not pity. Flushed with anger for Odysseus, Menelaus curses the cowards who would “steal the bed” of a better man and vows to tell what he learned from the Sea God.

The stories end in sleep; at sunrise, the prince is honored again as guest, proof that proper xenia still survives.

Back on Ithaca, the ambush is set; Athena, however, sends a consoling dream to steady Penelope.

Book 4 braids glamour and dread: human feasting and courtesy frame a god’s hard truth about Odysseus, even as a murderous welcome waits at home.

Book 5 — The Nymph and the Raft

Release begins not with mercy but with an argument among immortals.

Athena presses Zeus; Hermes descends; Calypso answers the decree with a rebuke that still stings across centuries. She says, “You cruel, jealous gods! You bear a grudge whenever any goddess takes a man to sleep with as a lover in her bed. ,” a sentence that turns obedience into indictment even as she yields.

Odysseus, meanwhile, is found weeping on the shore, desire braided to endurance. He will accept freedom at the price of new danger.

First comes craft.

He fells trees, measures planks, and rigs a square-sailed raft with a shipwright’s care.

“Even so he turned his hands to the craft,” Homer implies, before the sea asserts its old sovereignty with a punitive storm. Ino24/Leucothea erupts from foam to offer the thin, improbable technology of survival—

“Here, take my veil and tie it round your middle; when you have reached land, cast it into the sea, and turn your face away”—a ritual of un-seeing that also marks a boundary between divine loan and human debt. He hesitates, then trusts; he binds himself to the mast and to chance; he prays to the river with the old grammar of supplication—“Hear me, lord; I am at your mercy; even the wanderer has claim upon your pity”—and the water stills enough to admit him. Five movements, then: decree; dissent; workmanship; catastrophe; passage to Scheria, naked, salt-scoured, alive.

The episode insists that liberation is neither clean nor final, only a different hazard with better prospects.

The sand receives him like a grave he can sleep in.

And the fig-tree’s roots, crossed and cool, make the first architecture of safety.

Thus Book 5 converts divine politics into human labor and finally into the modest miracle of breath restored.

Book 6 — Princess at the River

Athena turns her attention to the Phaeacians of Scheria25, recalling how King Nausithous26 once moved them from Hyperia and how Alcinous27 now rules.

Disguised as Nausicaa28’s friend, Athena slips into the princess’s dream and scolds her about the heap of unwashed clothes, hinting at marriage on the horizon. She urges an early trip to the washing pools and promises to help. The goddess advises Nausicaa to ask her father for a mule-drawn wagon to carry linens to the river.

At dawn Nausicaa, shy to speak of marriage, persuasively asks her father for the cart. He agrees at once, and the household readies food, garments, and the wagon for the outing.

Nausicaa and her handmaids wash the clothes, eat, then play ball by the river.

Their cries wake the shipwrecked Odysseus, who emerges from hiding and respectfully appeals to the princess for help.

Nausicaa shows poise and compassion: she provides clothing and directs Odysseus to bathe and regain his dignity. She then gives shrewd instructions—he must follow the wagon later, enter the city apart from her to avoid gossip, and supplicate her mother, Queen Arete, for a safe return. She points him to Athena’s sacred grove near town to wait until she reaches the palace. At sunset, Odysseus prays in the sanctuary; Athena hears but stays hidden out of deference to Poseidon’s anger.

Nausicaa drives the mules home while Odysseus remains in the grove, trusting Athena’s guidance and the princess’s plan. He now has a clear path toward help in Scheria.

Thus Book 6 ends with hospitality already in motion, setting up Odysseus’s reception at the Phaeacian court in the next book.

Book 7 — A Magical Kingdom

Athena guides Odysseus through Scheria “in mist with which Athena covered him,” steering him toward Alcinous’s shining palace.

Before he enters, the goddess (as a girl) briefs him: “First greet the queen. Arete is her name.” She adds that in Phaeacia, “No woman is honored as he honors her,” so supplicating the queen is Odysseus’s safest path. If Arete’s heart is kind, “you have a chance of seeing those you love.”

Inside, the palace dazzles: “The walls were bronze all over… and along them ran a frieze of blue.” At the doors stand “silver and golden dogs… made by Hephaestus… unaging for all time,” signifying divine craft and royal security.

Odysseus follows Nausicaa’s plan and supplicates the queen: “He threw his arms around Arete’s knees.”

A hush falls until the elder Echeneus reminds them of sacred hospitality: “it is not right to leave a stranger / sitting there on the floor beside the hearth.”

Alcinous immediately acts: he “reached for Odysseus’ hand, and raised / the many-minded hero from the ashes,” seats him, and has him washed and fed. He orders “wine to be poured, so we may make libations / to Zeus,” and the steward mixes “the sweet, delicious wine… with first pour for the gods.” Then the king addresses his lords—“Listen, lords. Hear what my heart commands”—and announces they will host the stranger, sacrifice, and “plan / how we may help his journey… until / he reaches home.”

As the meal settles, Arete’s keen eye takes in the guest’s garments; the queen is “extremely clever and perceptive,” and the clothing is her own handiwork. Odysseus tactfully explains that Nausicaa rescued and dressed him, preserving the princess’s reputation.

Satisfied, Alcinous promises further aid and a proper send-off at dawn, while Odysseus—“half-starved and weak”—finds rest at last among generous hosts.

Book 8 — The Songs of a Poet

At Alcinous’s feast, “The boy took down the lyre from its peg / and took Demodocus’29 hand” to begin a day of songs, games, and revelations.

At dawn the Phaeacians gather, a ship is prepared for the guest, and the court turns to entertainment—“Many young athletes stood there,” ready to display their prowess. Alcinous sketches their culture’s ideals: “We are / not brilliant at wrestling or boxing, / but we are quick at sprinting, and with ships / we are the best. We love the feast, the lyre, / dancing and varied clothes, hot baths and bed.”

Demodocus is led out with his lyre, and the festival mood swells around the mysterious stranger.

Alcinous’s son Laodamas sizes up the newcomer and urges a try at sport: “Now my friends, we ought to ask the stranger / if he plays any sports.” Odysseus demurs—“My heart is set on sorrow, not on games”—but Euryalus snaps, “Stranger, I suppose / you must be ignorant of all athletics.”

Stung, Odysseus proves himself and rebukes the insult: “The gods do not bless everyone the same, / with equal gifts of body, mind, or speech.”

The games give way to display and dance as Alcinous calls for spectacle and for “the well-tuned lyre… for Demodocus—go quickly!”

Now the poet sings the famous scandal: “the love of fair-crowned Aphrodite / for Ares,” and how Hephaestus30 forged “chains so strong that they could never / be broken or undone,” snaring the lovers in bed. Gods crowd the doorway and “burst out laughing… at what a clever trap Hephaestus set,” while only Poseidon refuses to laugh and guarantees bail—“I promise he will pay.” Delighted, Odysseus honors the bard—“You are wonderful, Demodocus!… You tell so accurately what the Greeks / achieved”—and then makes his bold request: “sing the story / about the Wooden Horse.”

Demodocus obeys: in Troy, “Some said, ‘We ought to strike the wood with swords!’… [others] said they should leave it / to pacify the gods,” until doom enters the city. Odysseus listens as the sack unfolds and then “was melting into tears; / his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman / weeps…,” unnoticed by all but the king beside him.

Alcinous gently halts the song and turns to the guest: “Stranger, now answer all my questions clearly… What did your parents name you?”—and the stage is set for Odysseus to speak at last.

Book 9 — The Name That Wasn’t

Alcinous invites the stranger to speak, and Odysseus begins—praising the bard (“it is a splendid thing to hear a poet”) before turning to “my own sad story.”

He names himself plainly: “I am Odysseus, Laertes’ son, / known for my many clever tricks and lies,” from the “rugged” isle of Ithaca, “but good at raising children.” He adds that although Calypso and Circe31 tried to keep him, “there is no sweeter thing / than his own native land and family.” Then he turns to the troubles Zeus has sent him since Troy32.

At Ismarus33 among the Cicones, his men ignore orders and linger; “We took their wives / and shared their riches equally,” and by dusk “Six well-armed members of my crew / died from each ship.”

A storm drives them on until the land of the Lotus-Eaters34, whose fruit makes men “forget about / our destination,” so Odysseus drags the dazed scouts back to the ships.

Sailing again, they reach the Cyclopes35—“They hold no councils, have no common laws,” each ruling his own cave by whim.

Odysseus leads twelve men to a giant’s cave, waits for its owner, and soon faces Polyphemus, who scorns guest-right and devours two men; a plan forms around strong wine and a sharpened stake. When the heated point is rammed home, “So did his eyeball crackle on the spear,” and the blinded Cyclops howls for help. His neighbors hear him cry, “My friends! Noman is killing me / by tricks, not force,” and they withdraw, fooled by the name.

At dawn the survivors slip out clinging beneath rams—Odysseus “curled… up underneath / his furry belly, clinging to his fleece”—while Polyphemus feels each back and misses the men beneath. They flee to the ship, “struck their oar blades in the whitening sea,” and put distance on the water.

But hubris bites: from far offshore Odysseus jeers, “Hey, you, Cyclops! Idiot!… You had no shame at eating your own guests!” and the giant heaves a rock that nearly swamps them.

Worse, the taunt earns a curse; Polyphemus prays, “Grant that Odysseus, the city-sacker, / will never go back home… or if… fated… let him get there late and with no honor, / in pain and lacking ships… and let him find / more trouble in his own house.”

Book 10 — Wind, Hunger, and a House that Sings

From the bag of winds to Circe’s isle—and the grim command to visit the dead.

Aeolus36 welcomes Odysseus and “gave me / a bag of oxhide leather… tied the gusty winds inside it,” so one breeze can carry them home. Near Ithaca, the crew “opened up the bag, and all the winds / rushed out at once,” driving them back. Spurned a second time, Aeolus roars, “Get out!… It is not right for me to help… a man so deeply hated by the gods.”

They reach Laestrygonia’s37 deceptive harbor “all surrounded / by sheer rock cliffs… a narrow mouth,” where other ships moor inside. Cannibal giants pelt the fleet with “boulders bigger than a man could lift… They speared them there like fish. A gruesome meal!”

Only Odysseus’ ship cuts the cables and rows clear “beyond the overhanging cliffs.”

They make landfall on Aeaea, home to “the beautiful, dreadful goddess Circe, / who speaks in human languages.”

A scouting party is welcomed with food and song, but Circe “drugged them with her special potion… pricked them with her wand; they went / into the pigsties.” Hermes meets Odysseus on the path and “gave me… a herb and showed its nature; it had a black root and a white flower; the gods call it ‘moly’,” protection against her spell. Odysseus resists, forces terms, and the men are restored. They recover in plenty—“every day / for a whole year we feasted there on meat / and sweet strong wine.”

When the men beg to go, Circe agrees—but adds one more task:

“Go to the house of Hades38 and the dreadful

Persephone39, and ask the Theban prophet,

the blind Tiresias, for his advice.

Persephone has given him alone

full understanding, even now in death.

The other spirits flit around as shadows.“

As they rouse at dawn to depart, disaster: “He fell down crashing headlong from the roof… His spirit went down to Hades”—Elpenor40 is dead.

Book 11 — The Dead

Odysseus sails to the sunless edge of Ocean and performs the dark rite “where the Cimmerians41 live… [and] destructive night / blankets the world,” opening the way to the dead.

He digs a trench and pours offerings—“honey-mix, sweet wine, / and lastly, water… I took the sheep and slit their throats… Black blood flowed out. The spirits came,” and fear grips him. First arrives Elpenor, begging for burial and a marker—“burn me… heap a tomb… and plant my oar on top.” Then Tiresias appears to disclose the way home.

The prophet warns that Poseidon’s anger dogs Odysseus and that safety depends on restraint: “leave the cattle… unharmed… you may get home,” but if the crew harms Helios’ herd, “I see destruction for your ship and men.” He also foretells the inland penance with an oar “until… someone will say you carry a winnowing fan,” after which Odysseus must sacrifice to Poseidon.

Only then does Odysseus let his mother drink; he tries to embrace her—“Three times I tried… but three times her ghost / flew from my arms, like shadows or like dreams.”

A parade of heroines follows; “They thronged and clustered round the blood.”

When he resumes, the warrior-dead speak: Agamemnon recounts his murder and warns about trust at home; Achilles, unconsoled by glory, declares, “I would rather work the soil as a serf… than rule all the breathless dead.” Ajax remains implacable and “refused to speak to Odysseus.” Odysseus also sees the torments below: Tantalus “straining to reach water with his hands,” forever teased by fruit, and Sisyphus42 “straining to push the stone,” forever thwarted.

After glimpsing Heracles’ image and many others, Odysseus withdraws from the clamoring shades and returns toward his ship.

He departs Hades armed with a plan: master desire, spare Helios’ cattle, atone to the Earth-Shaker, and only then will home be possible.

Finally, he carries back his mother’s charge to “remember all these things,” for they will guide the living through the counsel of the dead.

Book 12 — Difficult Choices

Circe warns Odysseus that the next leg of his homeward voyage will force him to choose among deadly perils.

Back on Aeaea, they bury the fallen Elpenor with full rites. Circe then lays out the hazards ahead—the Sirens’43 song, the twin threats of Scylla44 and Charybdis, and the sacred cattle of the Sun—and urges speed and restraint. Forewarned, Odysseus briefs his crew, orders wax in their ears, and has himself lashed upright to the mast.

They slip past the Sirens; the crew rows on, deaf to the meadow’s lure, while Odysseus rages to be released as their voices promise total knowledge and immortal fame. Bound fast, he alone hears the danger and survives the temptation.

Then the ship enters the strait where Scylla haunts one cliff and Charybdis45 swallows the sea beneath a leafed fig tree on the other.

Despite Circe’s counsel not to fight, Scylla snatches six of the best men in a single rush, the most heart-rending sight of the voyage.

Shaken, they reach Thrinacia, the Sun God’s pastures, and—storm-bound, starving—swear not to touch the herds. While Odysseus naps, Eurylochus46 goads the men to slaughter the divine cattle, arguing a swift death beats wasting away. Portents follow; the hides crawl and the meat bellows on the spits. When the winds relent and they put to sea, Zeus strikes: the ship shatters under thunder and flame, and every sailor but Odysseus is drowned.

Alone, Odysseus is swept back through the strait, clinging to a fig tree above Charybdis, then to a shattered timber to slip past Scylla’s rock. After ten days adrift, he washes up on Calypso’s47 island, where his tale will eventually circle back to the beginning.

These “difficult choices” show how survival depends less on glory than on restraint, timing, and endurance.

Book 13 — Home, Under a Fog of Recognition

The Phaeacians ferry Odysseus home as he sleeps, lay him and his treasure on Ithaca’s shore beside the cave of the Nymphs, and sail away.

Poseidon complains to Zeus that mortals slight him and asks permission to punish the helpers who returned Odysseus. He turns the homebound Phaeacian ship to stone in full view of its people, confirming an old prophecy. King Alcinous orders them to stop conveying travelers and to sacrifice to appease the Earth-Shaker48.

Meanwhile, Odysseus wakes on his own island but cannot recognize it, because Athena has masked Ithaca in a mist. She comes to him first as a handsome young shepherd and strikes up a cautious conversation.

He answers with a swift Cretan lie; she smiles, reveals herself, and praises the cunning that matches her own.

Together they hide the gifts in the Naiads’49 cave and begin to plan how to destroy the suitors.

Athena sketches the danger in Odysseus’ house and the need for stealth. Keeping the island fog-bound, she shifts guises—from polished youth to a splendid woman—to make herself known to him and to underline their shared talent for disguise. Then she transforms Odysseus into a ragged old beggar so he can move unrecognized among his enemies. She herself departs to fetch Telemachus from Sparta. Odysseus, now altered, steels himself to approach trustworthy allies first.

The poem pivots from sea-roaming adventures to a home-front campaign of patience, deception, and reconnaissance. Recognition will be staged, with Athena coaching the master of lies.

Under this fog of recognition, homecoming begins not with embrace, but with strategy.

Book 14 — The Loyal Swineherd

Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, follows Athena’s lead to the swineherd Eumaeus’50 remote hut above Ithaca’s shore.

The yard dogs rush him, but Eumaeus drives them off and brings the stranger inside, offering rough shelter and a meal. Grieving his long-absent master, the swineherd condemns the suitors and vows steadfast loyalty to the house of Odysseus. The guest hints that Odysseus lives and will soon return.

To win trust without revealing himself, Odysseus spins a layered Cretan tale.

Odysseus claims to be a Cretan warrior, the son of a wealthy man named Castor, who fought bravely in Troy. After returning home, he says he was drawn into more adventures—sailing to Egypt, where he was tricked by a deceitful Phoenician who plotted to sell him into slavery. He describes being shipwrecked and enslaved, eventually landing in Thesprotia, where he supposedly heard that Odysseus was still alive. From there, he says he was again deceived and carried off to Ithaca, where he escaped and found refuge in Eumaeus’s hut.

Eumaeus answers that such traveling liars are common and he refuses to believe it.

Even so, the swineherd practices generous xenia, feeding his guest from his scant stores.

He slaughters a prime pig, prays that his true lord come home, and honors the gods before dividing the meat.

Night brings a test of hospitality: Odysseus tells a sly story from the Trojan War about tricking a comrade into lending him a cloak on a freezing watch, a parable meant to prompt charity without begging outright. Pleased by the tale, Eumaeus fetches a warm cloak and bedding for his guest, then takes the harsher duty for himself, sleeping outside with the pigs to guard his master’s property. Their talk fixes Eumaeus as the poem’s “noble slave,” loyal in word and deed despite poverty and danger. The beggar’s promise that Odysseus will return soon lingers as both hope and ruse.

At dawn they eat again and discuss whether the stranger should risk town to beg among the suitors. Eumaeus forbids it, warning that their violence “reaches the iron sky.”

The swineherd’s cottage becomes a safe staging ground, where patience, secrecy, and care for the household replace battlefield glory.

Book 15 — The Prince Returns

Atena hustles Telemachus out of Sparta and sets the board for homecoming and payback.

She warns him the suitors lie in ambush and orders a stealthy route home and a first stop with the “better than most slaves” swineherd. She says, “You should no longer travel so far from home… with greedy men at home,” and adds, “there is a gang of suitors… who have plans to kill you.”

She maps his return—sail day and night, land, send the crew to town, and go alone to Eumaeus. Back in Sparta, Menelaus and Helen load him with gifts and speed him off.

An omen breaks over the departure: an eagle clutching a house goose.

Helen reads it bluntly—“so will Odysseus… come back and take revenge… planting ruin for the suitors.”

On the beach, Telemachus picks up the fugitive seer Theoclymenus.

Meanwhile, in the hut, Eumaeus urges the disguised Odysseus to stay and, when pressed for his past, opens a floodgate: “These nights are magical… after many years / of agony and absence from one’s home, / a person can begin enjoying grief.”

Near Ithaca, the prince chooses caution—he sends the crew to town while he visits the herdsmen first. “You all should drag the ship towards the town, while I go visit the herdsmen… Then I will come to town.” A hawk flashes rightward, a pigeon in its talons, feathers “scattered between the ship and young Telemachus.”

Gripping the prince’s hand, Theoclymenus declares the omen: “Some god has sent this bird… No family in all of Ithaca has greater power; you are the kings forever.”

Telemachus places the prophet with trusty Piraeus—insurance if the suitors strike first.

Back in Ithaca, he slips toward Eumaeus’s pens as the plot converges. And at the palace, the suitors’ smiles still hide murder.

Book 15 closes with momentum and foreboding: the gods point the way, omens promise justice, and father, son, seer, and swineherd draw into position for the reckoning to come.

Book 16 — Father and Son

Telemachus reaches the swineherd’s yard at dawn; the dogs fall silent, and Eumaeus rushes to him weeping—“Sweet light! You have come back, Telemachus.”

Inside, they share bread, meat, and wine, and Telemachus asks who the “stranger” is. Eumaeus repeats the beggar’s tale of Cretan wanderings and offers him up as Telemachus’ suppliant. The prince vows clothing and food but adds that the suitors must not see the man; “they are much too violent.”

Telemachus dispatches Eumaeus to carry news to Penelope. Athena comes, lifts the disguise, and “transforms Odysseus, so he looks young and strong again,” revealing the father to the stunned son.

They weep together and turn at once to strategy: a secret return and a purge of the hall.

Odysseus orders the classic ruse—hide the armory and keep two sets: “Leave out two swords, two spears, and two thick shields for you and me.”

He layers on caution—“let no one know that I am in the house… not even Penelope”—and instructs his son to test the household’s loyalty. Telemachus, “glowing,” accepts but trims the plan: learn which women are faithful now; the men can be tested later. Meanwhile, town erupts: word spreads the prince is safe; the suitors convene to salvage their plot, but Amphinomus51 balks—“I for my part have no desire to kill Telemachus.” Penelope descends blazing and calls out Antinous: “You are a brute! A sneak! A criminal!”

At dusk, Athena touches Odysseus again, ragging him out before Eumaeus returns, and the three share a quiet meal. The father tells his son, “I will again be looking like a beggar… just watch, and keep your temper—truly now their day of doom is near at hand.”

Plans fixed, Telemachus heads for the palace at dawn while the “stranger” will follow with the swineherd.

“Soon, in my house the god of war is testing our fighting force and theirs,” Odysseus promises—and Book 16 closes with father and son aligned in secrecy and resolve.

Book 17 — Insults and Abuse

Telemachus leaves for town at dawn and tells Eumaeus to bring the “poor old stranger” to beg his supper.

At the palace, Eurycleia notices him first, and Penelope rushes down “like Artemis or golden Aphrodite,” crying, “You came! Telemachus! Sweet light!”

He asks her to bathe, pray, and hope that “Zeus may grant / revenge,” while Piraeus brings the seer Theoclymenus inside. Meanwhile, Eumaeus sets out with the disguised Odysseus toward town.

At the fountain, they meet the goatherd Melanthius, who heaps insults and kicks the beggar; Eumaeus prays for payback. Outside the halls, the old dog Argos recognizes his master and dies, the first silent “welcome” home.

Inside his own house, Odysseus begs. Telemachus quietly gives him food and tells him to ask from all the suitors. “They each give him scraps, except Antinous,” who soon turns violent.

Earlier that morning, the “stranger” had said what he would do: “Beggars should wander round the town and country… I will get food from charitable people.” What he gets instead is abuse: Antinous hurls a footstool at him, prompting Odysseus to curse the ringleader as the other suitors reproach such cruelty.

An omen ripples the moment—Telemachus sneezes—and Penelope, moved, sends word for the beggar to meet her, promising clothing “if he tells her the truth” about Odysseus. Odysseus wisely postpones the talk until night, keeping the ruse intact.

Thus Book 17 shifts the epic’s battlefield to etiquette and appetite, where true character shows in how one treats a hungry guest.

Melanthius and Antinous fail the test of hospitality; Eumaeus and Telemachus pass it.

Under insults and abuse, Odysseus’ patience sharpens the coming reckoning.

Book 18 — Two Beggars

Irus, a gluttonous town beggar, tries to bully the ragged Odysseus off his own threshold—“Get away, old man!… Or we must fight!”

Antinous eggs on a bout and makes the men swear not to interfere, while Odysseus “took off his rags… revealing massive thighs and mighty shoulders,” stunning the crowd. He drops Irus with a single blow—“broke his jaw… red blood gushed”—then drags him outside and warns him not to “bully visitors and beggars.” Cheering, the suitors reward the “stranger” with meat and wine.

Odysseus quietly pulls Amphinomus aside and counsels prudence: “Of all the creatures… we humans are weakest,” our fortunes shifting with Zeus. Hinting the husband will return “very soon,” he urges the decent suitor to leave before the reckoning.

Athena then inspires Penelope, bathing her in “ambrosial beauty” so that the suitors “weakened at the knees.”

She descends and rebukes Telemachus—“you allowed a guest to be insulted… You will be shamed!”—pressing him to uphold household honor.

Playing the room, Penelope recalls Odysseus’ words that when their son “has grown a beard,” she must remarry, then coolly teaches proper courtship: “They ought to bring fat sheep and cows… and give fine gifts, not eat what is not theirs.”

Eurymachus flatters her—“no other woman equals you in beauty, stature, and well-balanced mind”—and the suitors compete with presents while Odysseus, delighted, notes she “was secretly procuring / presents.”

The hall’s mood curdles when Melantho and others sneer at the “stranger,” and Eurymachus turns abusive. Odysseus endures, letting their gifts and arrogance pile up as evidence.

Eurymachus finally hurls a stool; Odysseus ducks and it smashes the wine-boy’s hand, and Telemachus—now firm—orders the revelers to leave. Amphinomus smooths things over so libations can be poured and the night can end.

Book 18 closes with two beggars, one broken and one unbroken, and with the suitors staggering home under a doom they were warned to avoid.

Book 19 — The Night of Tests

Odysseus and Telemachus begin the night by clearing the hall of weapons, laying the groundwork for the reckoning to come.

They lock the women away, carry helmets, shields, and spears to storage, and blame the removal on “soot” and drunken brawls if anyone asks. Athena stands by them with a golden lamp and makes “majestic light,” and Telemachus whispers that the rafters gleam “as if a fire were lit.” Odysseus hushes him: “Hush, no more questions… This is the way of gods from Mount Olympus,” then sends the boy to bed while he stays to “make [Penelope] cry, and let her question me.”

Penelope descends “like Artemis or golden Aphrodite,” and the house prepares for a private interview with the “stranger.” Melantho52 is rude; Penelope scolds her, reasserting a mistress’s dignity over a house gone astray.

The queen questions the beggar; he answers with a crafted Cretan tale that makes her weep for her husband.

Then Penelope orders a footbath; Eurycleia53 feels the old hunting scar and gasps, “You are Odysseus! My darling child! My master!”

He clamps a hand to her throat—“Be silent; no one must know”—and threatens death if she betrays him; she swears to be “as strong as stone or iron,” even offering to name the guilty and the good among the women. The nurse finishes washing and hides the scar with rags. Penelope speaks of the pain that keeps her wakeful “like the… nightingale… in mourning” and asks the stranger to interpret a dream of an eagle that kills her geese; the bird’s voice insists, “This is no dream; it will come true.” Odysseus, “well-known for his intelligence,” says plainly the dream “means ruin for all the suitors.”

At last Penelope announces a test: tomorrow she will set out Odysseus’ axes and offer herself to “whoever strings his bow… and shoots through all twelve axes.”

The beggar urges her “do not postpone this contest,” promising the suitors will fail before “Odysseus, the mastermind, arrives.”

Thus Book 19 closes under a conjured lamplight of truth and disguise—recognition delayed, the test chosen, and vengeance almost at the door.

Book 20 — Omens at Breakfast

Odysseus spends a tense night in his own hall as fate tightens around the suitors.

Sleepless on an oxhide, he sees the slave girls slip out to meet their lovers and wrestles down a murderous impulse, thumping his chest: “Be strong, my heart. You were / hounded by worse the day the Cyclops ate / your strong companions” . Athena appears, promising he will soon “distance [himself], Odysseus, from trouble,” and lulls him to rest . At dawn he prays for a sign, and Zeus answers with thunder from a clear sky .

Inside, an exhausted mill-slave pauses her grinding and prays that this will be “the last day that the suitors dine in style… My knees are sore,” which Odysseus takes as a blessed omen for vengeance . Preparations for a festival meal fill the house as Eurycleia organizes the servants and Telemachus arms himself for the day’s dangers .

On the road and in the court, Melanthius spits insults, while the herdsman Philoetius greets the “beggar” kindly and quietly swears loyalty; Odysseus notes who stands with him (and who will fall).

By breakfast, omens and prayers have stacked the deck against the suitors.

Telemachus seats the “beggar,” warns the room against abuse, and the swaggering Ctesippus “hurled a cow’s hoof” at Odysseus, prompting the prince’s cold rebuke and a vow that he could have answered murder with murder .

Tension breaks into eerie hilarity as Athena “makes the suitors laugh unstoppably” and their meat seems blood-spattered to prophetic eyes (an omen also shadowed by an unlucky left-hand eagle noted that day) . Banter turns sour; the men jeer at Telemachus, who endures in silence, while loyal swineherd and cowherd keep watch.

In the background, Zeus’ thunder and the slave’s aching-kneed prayer keep ringing—small voices that promise large reckonings . The hall is ready; the trap is nearly sprung.

The seer Theoclymenus finally speaks, saying he sees darkness flooding the house and “cheeks wet with tears,” that “the courtyard is full of ghosts, and down / the hall to darkness, past the doors, they go,” before he wisely departs .

Book 20 closes with father and son playing for time, the suitors laughing at their own funeral feast.

Book 21 — The Bow and the Axes

Penelope, prompted by Athena, decides the time has come to set the contest that will “begin the slaughter.”

She unlocks the storeroom “with true aim” and brings out Odysseus’ great bow and the twelve axes, then declares, “If anyone can… string it easily, and shoot through all twelve axes, I will marry him.” Eumaeus sets the gear; he and the cowherd “wept… when he saw his master’s bow,” while Antinous snaps at their loyalty. Telemachus laughs at fate, announces he will try first, and prepares the range himself.

Three times he strains for the string and three times he fails; on the fourth he stops at a sign from his father.

Leodes, the suitors’ “holy man,” also fails and warns, “This bow will take away courage, life-force, and energy from many noble young men.”

Grease, fire, and pride do not help: the suitors warm and rub the bow, yet cannot string it, and talk of postponing the trial.

Outside the gate, Odysseus tests his last allies and reveals himself—“See my scar… made by the boar’s white tusk”—winning the sworn aid of Eumaeus and Philoetius.

Back inside, Eurymachus argues it would shame them if “some random beggar… strung it easily,” but Penelope answers, “The stranger is quite tall and muscular… give him the bow.” Telemachus asserts himself—“The bow is work for men, especially me. I am the one with power in this house”—and sends his mother upstairs.

Antinous cries off for the feast day of Apollo, but Odysseus smoothly urges a try “at dawn,” planting the ruse that buys him the chance. On the prince’s orders, Eumaeus places the bow in the “competent” stranger’s hands, Eurycleia locks the women in, and Philoetius bars the courtyard gate.

Then, in utter hush, Odysseus strings the bow “easily” and sends a shaft through all the axes in a single, flawless shot.

The room gapes; the contest is over, but the reckoning has just begun.

Book 21 ends with the weapon tuned to its true owner and the hall sealed—next comes the arrow for Antinous.

Book 22 — Bloodshed

Odysseus rips off his rags, prays “Apollo, may I manage it!” and shoots Antinous through the throat as he lifts his golden cup, “thick streams of blood” soaking the feast.

The suitors leap up, shouting for shields that aren’t there, and threaten the “stranger.” Odysseus answers with the verdict: “Dogs! … you thought no man would ever come to take revenge. Now you are trapped inside the snares of death.” Eurymachus tries to bargain—blame Antinous, repay the loss—but the trap has already sprung.

Fighting erupts: the suitors, “armed only with chairs and side tables,” rush the four defenders, but arrows and spears answer them; Telemachus kills Amphinomus and runs for the storeroom. Melanthius slips to the arms room and starts handing out weapons.

Eumaeus and Philoetius intercept the traitor and “truss him up,” suspending him from a beam to stop the flow of arms.

Athena appears as Mentor, then lifts her aegis: the suitors scatter “like cattle, roused and driven by a gadfly,” while “screaming filled the hall… the whole floor ran with blood.”

In the melee, Leodes the priest grabs Odysseus’ knees—“Please, mercy! … I tried to stop the suitors”—but the king replies, “You will not escape. Suffer and die!” and cuts off his head. Phemius the bard chooses supplication instead—“I am self-taught… Wait, do not cut my throat!”—and Telemachus urges, “Stop, hold up your sword—this man is innocent,” saving both poet and herald Medon. Odysseus agrees: “Live and spread the word that doing good / is far superior to wickedness.”

Soon the suitors lie “like fish hauled up… they gasp for water,” and silence returns.

Odysseus calls for Eurycleia.

Then comes the house’s ugliest reckoning: Odysseus orders the disloyal women killed; Telemachus refuses them a “clean death” and hangs them instead, while Melanthius is mutilated.

With the hall purged, Odysseus sends the spared men outside and has Eurycleia summoned—Book 22 ends in blood and breathless stillness before the next test.

Book 23 — The Olive Tree Bed

Eurycleia wakes Penelope with glee to say the “old beggar” is Odysseus and that he has “slaughtered all the suitors who were wasting his property and threatening his son.”

Penelope refuses to be fooled—“You poor old thing! The gods have made you crazy”—and warns she will punish any slave who spreads “silly stories” in her grief. Eurycleia insists, “Odysseus is here! / He is the stranger that they all abused,” adding that Telemachus kept the plan secret so his father could take revenge. Penelope leaps up, embraces the nurse, and asks how one man could have overcome so many.

Meanwhile Odysseus sets a ruse—music and dancing “so passersby or neighbors” will think it a wedding—while Athena bathes and beautifies him “from head to toe.”

He sits opposite his wife and snaps, “Extraordinary woman!… This woman / must have an iron heart!”

Penelope tests the stranger: “Eurycleia, make the bed for him outside the room he built himself.”

Odysseus flares—“Woman! Your words have cut my heart! Who moved my bed?”—then recounts the secret of their marriage token: a bedroom built around a “full-grown” olive whose trunk he carved into a bedpost, with “gold and silver and… ivory” inlay and “ox-leather straps… dyed purple.” He ends, “Now I have told the secret trick, the token,” a detail only he, Penelope, and one slave could know. Penelope’s body “suddenly relaxed”; she runs to him, crying, “Do not be angry at me now… The gods have made us suffer,” and admits, “Now you have told the story of our bed, / the secret that no other mortal knows.”

Their embrace evokes shipwrecked survivors crawling to shore, “their skin all caked with brine.”

They trade stories through the night, and he tells of the further journey yet to come, though he keeps some adventures “edited.”

To buy time with the townsfolk, Odysseus orders the wedding-noise charade to continue at daybreak.

“Finally, at last, / with joy the husband and the wife arrived / back in the rites of their old marriage bed.”

Book 24 — Restless Spirits

Hermes “called the spirits of the suitors out of the house,” and they followed him “squeaking like bats,” down to the asphodel meadows of the dead.

In Hades, Achilles and Agamemnon trade stories; then the new‐arrived ghosts are hailed and questioned. Amphimedon tells how the suitors died in Odysseus’ hall, and Agamemnon—thinking of Clytemnestra—growls, “Not like my wife—who murdered her own husband!” He marvels that Odysseus has a faithful, intelligent spouse.

Meanwhile, Odysseus slips out to the countryside to see Laertes and—true to form—decides, “I will test my father.” The old man collapses in grief until Odysseus reveals himself with the scar and the orchard roll call: “Ten apple trees… thirteen pear trees, forty figs, and fifty grapevines.”

Athena then “made him grow taller and more muscular,” restoring Laertes’ strength.

But Rumor flies; the town gathers and mourns.

Eupeithes, father of Antinous, ignites revenge: “This scheming man… murdered all the best of Cephallenia… We have to act!” Medon and the bard swear a god helped Odysseus, and Halitherses warns, “We must not go and fight,” yet “more than half” arm for battle anyway. On Olympus, Athena asks Zeus whether to end or extend the war; he answers the plan was hers—revenge and then peace. In the field, Laertes—newly nerved by the goddess—hurls his spear and kills Eupeithes; Odysseus and Telemachus charge as Athena cries, “Ithacans! Stop this destructive war; shed no more blood.” A thunderbolt halts Odysseus; she orders peace and “made the warring sides swear solemn oaths.”

“Let them all be friends… and let them live in peace,” Zeus decrees, and Athena enforces it.

Thus the epic ends not in embrace but in an imposed truce, leaving home and peace achieved only by divine interruption.

4. The Odyssey Analysis — Characters

4.1 Character Analysis of The Odyssey

Odysseus — the many-minded hero.

Homer frames Odysseus as a shape-shifter: master rhetorician, teller of “tall tales,” and strategist whose identity flexes to fit each trial and audience; the poem’s recognition scenes showcase how different characters perceive a different Odysseus.

Penelope — prudent partner and tester.

Penelope’s caution and intelligence counterbalance Odysseus’s cunning; she delays certainty, then forces the decisive “bed test,” leveraging household knowledge to confirm identity and reclaim mutual power.

Telemachus — from boy to heir.

Tagged “thoughtful,” Telemachus matures through travels and modeled hospitality, yet truly comes of age only when reunited with his father and drawn into the plan against the suitors.

Athena & Poseidon — divine bookends.

Athena enables recognitions and strategy, while Poseidon’s wrath supplies the long arc of delay; together they externalize help and hindrance to human agency.

Eurycleia & Eumaeus — loyal household pillars.

Eurycleia, the old nurse, keeps crucial secrets and literally “keeps house,” including the scar recognition and securing the women’s quarters before the bow trial; Eumaeus models steadfast xenia and identification with the household’s good.

The Suitors (Antinous, Eurymachus) — social rot.

Their abuse of xenia and parasitic consumption invert the heroic code; the bow contest crystallizes the moral reckoning that follows.

Women’s work, men’s work — the social stage.

Homer’s world divides labor and space by gender; figures like Eurycleia and Eurynome reveal the domestic skills and bodily care that underwrite elite life, setting the stakes of Penelope’s choice.

Monsters & hosts (Circe, Calypso, Nausicaa, Polyphemus) — mirrors of identity.

Each encounter refracts Greek ideals of hospitality, craft, and self-rule; Odysseus’s own storytelling and piracy-adjacent exploits complicate heroism as much as they celebrate it.

The Odyssey builds character through social roles (guest/host, master/slave, spouse/parent) and through recognition scenes that test names, bodies, and memories—making identity itself the poem’s central adventure.

4.2. The Odyssey Themes & Symbolism

1) Homecoming (nostos) & the fragility of identity

The poem treats “recognition” as the engine of homecoming—each character knows a different Odysseus, and identity is proved by scars, memories, and private signs.

2) Cunning (mētis) vs. force

Odysseus’ power lies in rhetoric and disguise; he spins “tall tales,” improvises personae, and solves problems with words before weapons—an ethic that both saves and imperils him.

3) Xenia (hospitality) as social order

Good hosts (Eumaeus, the Phaeacians) and parasitic guests (the suitors) mark a moral map of Greece; the bow contest becomes a ritualized judgment on abuse of the feast.

4) Household, labor, and slavery

Behind elite heroism sits a world of gendered work and coerced service: women grind grain, weave, bathe guests; men herd, pour wine, fight. Eurycleia and Eumaeus personify loyal labor that holds the house together.

5) Gender, power, and delay

Penelope’s caution and tests (especially the “bed test”) show female intelligence shaping fate from the “inner rooms,” balancing Odyssean mētis with feminine prudence.

6) Storytelling as mastery

Odysseus’ self-narration—swapping origins, crafting myths—exposes the poem’s meta-theme: identity is told into being. Each recognition scene doubles as an editorial on how stories persuade.

7) Empire, raiding, and the ethics of heroism

The text blurs “hero” and “pirate”: sacking cities and stealing wealth sits uneasily beside Greek colonizing ambition; Polyphemus becomes a foil through which conquest is rationalized.

8) Divine agency vs. human choice

Athena’s guidance and other gods’ obstructions frame human craft within a world of interventions—recognition and timing often depend on the goddess’s help.

4.3 Symbols & Motifs

The scar — Bodily memory.

Eurycleia’s discovery of the leg scar authenticates the man beneath the mask; the body “remembers” when words could lie.

The olive-tree bed — Marriage rooted in the house.

Built around a living trunk, the bed fuses conjugal bond and architecture; moving it would destroy both tree and home—hence Penelope’s decisive test.

The bow and the axes — Right rule and rightful skill.

The contest ritualizes political legitimacy: only the true oikodespotēs can string the bow and realign the house’s order. (Penelope withdraws; Eurycleia locks the women; the stage is set for judgment.)

Food and feasting — Moral barometer.

Banquets reveal virtue or rot: generosity marks good hosts; gluttony, mockery, and waste mark the suitors’ social crime.

Weaving & unweaving — Time and agency.

Penelope’s craft delays remarriage and buys knowledge; “women’s work” becomes strategic timekeeping for the plot.

Sea travel — Risk, change, and rebirth.

The ocean’s flux mirrors Odysseus’ mutable self, where survival depends on adaptation and the right tale told at the right shore.

Dogs, doors, and thresholds — Liminal recognitions.

From Argos to storerooms and locked chambers, thresholds mark the shifts between disguise and disclosure, chaos and restored order.

The Odyssey binds its big ideas—homecoming, cunning, social order, and power—to household things: beds, bows, scars, food. The epic’s symbolism grounds cosmic journeys in the intimate politics of a single house.

5. Evaluation

Its strengths are legion: a propulsive, speech-driven style; set-pieces (Cyclops, Sirens, Scylla/Charybdis) that balance myth and psychological realism; and an ethics that resists sermonizing.

Some readers feel pacing whiplash (domestic suspense vs. travelogue), and the final punitive scenes, including the maids’ execution, demand tough classroom framing rather than blind celebration.

Personally, the line that never leaves me is the quiet death of Argos after he recognizes his master—proof that fidelity can outlive neglect.

Compared with Iliad’s battlefield fatalism, the Odyssey is the literature of repair.

For adaptations, two touchstones show opposite strategies: the Coen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? (a Depression-era transposition) earned roughly $71.9M worldwide across releases, indicating ongoing popular appetite for Homeric retellings; NBC’s 1997 miniseries The Odyssey won the Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Directing and was widely nominated, proving the story’s TV legs.

As for “box office vs. book,” that’s the point: the poem scales from lecture hall to living room because it’s built on repeatable patterns—hospitality tables and recognition scenes—that film loves.

The impact is contemporary, not antique.

And the cultural data backs this: BBC Culture’s poll ranked Odyssey the number-one story that shaped the world, while classroom metrics—editions, citations, and translation cycles—keep accelerating (witness the Wilson and Norton Critical boom).

6. Personal insight

Reading the poem alongside Emily Wilson’s introduction helps students parse xenia as both refuge and soft power—useful when teaching civic life, migration ethics, or even platform moderation (who gets invited in, on what terms?).

For cross-reading, Probin Islam’s site has recent essays on Greek-myth retellings (Circe) and lists recognizing the Odyssey’s outsized influence—good on-ramps for general audiences and SEO-minded educators curating further reading.

Two quick classroom moves: pair Book 9’s Cyclops scene with a seminar on “hospitality vs. security,” and end with the bed-test as a case study in evidence, consent, and trust.

7. Odyssey Quotes

“Tell me about a complicated man.”

“Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost.”

“Tell the old story for our modern times.”

“This is absurd, that mortals blame the gods!”

“They say we cause their suffering, but they themselves increase it by folly.”

“When rosy-fingered Dawn came bright and early,”

“Poor fools, they ate the Sun God’s cattle.”

“There is no way to hide a hungry belly.”

“Shame is not a friend to those in need.”

“Zeus halves our value on the day that makes us slaves.”

“Woman! Your words have cut my heart!”

“Who moved my bed?”

“Now I have told the secret trick, the token.”

“Do not be angry at me now, Odysseus!”

“In tears he stared across the fruitless sea.”

“Stop grieving, please. You need not waste your life.”

“Out on the wine-dark sea.”

“Help yourselves! Enjoy the food!”

“Eumaeus! This is Odysseus’ splendid palace.”

“I have been hit before. I know hard knocks. I am resilient.”

“You are Odysseus! My darling child! My master!”

“He wiped his tears away and hid them easily.”

“Slaves do not want to do their proper work, when masters are not watching them.”

“The gods have given you the hardest heart.”

8. Conclusion

If you want a single, durable curriculum for courage, tact, and return, read the Odyssey—it meets you where you are and walks you back home.

For myth-heads, teachers, founders, and policymakers, it’s a model of decision-making under radical uncertainty; for readers craving only battles, it may feel domestic, but that hearth is the point.

Across time, this epic keeps proving why the oldest stories are also the newest: they name our problems before we do and hand us rituals for repair.

9. FAQs

- What is The Odyssey about?

Odysseus’s 10-year journey home from Troy and the struggle to restore his household in Ithaca. - Who wrote it and when?

Traditionally Homer, composed in archaic Greece (late 8th–7th century BCE). - What does “odyssey” mean?

A long, adventurous journey—named after Odysseus and his homecoming (nostos). - Who are the main characters?

Odysseus, Penelope, Telemachus, Athena, Poseidon; key figures include Eumaeus, Eurycleia, and the suitors (Antinous, Eurymachus). - What are the core themes?

Homecoming, identity and recognition, cunning vs. force, hospitality (xenia), fate vs. free will. - Why is hospitality so important?

It’s the moral litmus test of the poem: good hosts are rewarded; abusers (the suitors) are punished. - What are the most famous episodes?

The Cyclops Polyphemus (Book 9), Circe (10), the Underworld (11), Sirens/Scylla/Charybdis (12), the bow contest and slaughter of the suitors (21–22). - How does Penelope verify Odysseus?

She orders their bed moved; Odysseus reveals it’s built around an olive tree—knowledge only he would have. - What’s the role of the gods?

Athena aids with strategy and disguise; Poseidon’s wrath prolongs the voyage—divine will frames human choices. - Why does the poem still matter?

It explores how identity is proven, how stories shape truth, and how justice and belonging are rebuilt after chaos.

Notes:

- A Latin expression that refers to a story, or the action of a play, etc. starting without any introduction ↩︎

- Odysseus’ only son; Books 1–4 (the “Telemachy”) follow his coming-of-age search for news of his father and later his role in the reckoning with the suitors. The poem’s glossary frames him precisely in that arc. The name is often parsed from Greek roots meaning “far” (tele-) and “battle” (machē), which resonates with how he begins at a distance from heroic combat and grows into it; note Homer’s toponym Telepylus glossed as “Far Gate,” which supports the “tele- = far” piece of this analysis. ↩︎

- Odysseus’ rugged home island and the poem’s endpoint; Telemachus lists neighboring islands (Dulichium, Same, Zacynthus) when tallying the suitors’ strength, which also sketches the Ionian geography of his little kingdom. Note Wilson’s remark that “Cephallenia” in the poem denotes Ithaca plus its subject towns ↩︎

- King of Ithaca, famed for intelligence and stratagem. Emily Wilson’s notes highlight the name’s connection to Greek odussomai (“be angry at,” “hate”) and the cognate odunē (“pain”), a pun the poem itself exploits when Autolycus “gives Odysseus his name.” The etymological play underscores how the hero both causes and suffers pain. ↩︎

- A sea-loving people on Scheria who escort strangers safely and lavishly; Odysseus calls them “famous for navigation” and they deliver him home asleep amid treasure. Their cultural profile as ideal hosts—and ferrymen—marks a threshold from concealment to homecoming. ↩︎

- King of gods; final arbiter whose thunder signals assent. He favors political order and, symbolically, the eagle; in Book 1 he validates Telemachus’ public stand with a two-eagle omen and later decrees Odysseus must be released from Calypso. ↩︎

- (Argeiphontes) — Messenger and mover between realms; orders Calypso to free Odysseus, equips him against Circe with moly, and later guides the suitors’ souls to Hades. His speed, trickster flair, and “golden sandals” mark him as a god of travelers. ↩︎

- A goddess on Ogygia, Calypso’s island “far out in the sea,” named in glossaries and dramatized in Odysseus’ own tale of shipwreck and seven-year detention., who detains Odysseus for years. The name transparently matches Greek kalýptō (“to cover, conceal”), and that is exactly her function in the plot—she keeps him hidden from the world until the gods intervene. ↩︎

- Phemius, introduced in Book 1 of The Odyssey, is the household bard who performs songs in Odysseus’ hall for the suitors who consume the absent king’s wealth. He is described as a “holy singer” or “loyal bard,” a man who plays the lyre and sings “of the disastrous homecoming of the Greeks from Troy,” a theme that moves Penelope to tears. ↩︎

- Odysseus’ wife, renowned for intelligence, emotional stamina, and strategic delay. The poem repeatedly highlights her “finer mind” and her famous stratagem of weaving and unweaving Laertes’ shroud to postpone remarriage; throughout Odysseus’ absence she resists “more than a hundred” suitors who eat and drink in her hall. Her ambiguity is purposeful—she tests as much as she is tested—culminating in the bed-root recognition. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, the Suitors are a group of over a hundred arrogant noblemen from Ithaca and nearby islands who occupy Odysseus’ palace during his long absence. They gorge themselves on his livestock and wine, exploiting the hospitality of his household while vying for Penelope’s hand in marriage, assuming Odysseus is dead.

They are portrayed as the poem’s main human antagonists, embodying greed, disrespect, and social decay. The two leading figures, Antinous and Eurymachus, plot to kill Telemachus and mock both the prince and the disguised Odysseus. A few, like Amphinomus, show mild decency, but all share in the crime of violating xenia, the sacred law of hospitality. ↩︎ - Antinous, in The Odyssey, is the most arrogant and violent of Penelope’s suitors—an embodiment of greed and impiety. He mocks Telemachus, plots his death, and abuses xenia (sacred hospitality). In Book 17, he hurls a stool at the disguised Odysseus—“He lifted up his stool and hurled it at Odysseus’ right shoulder”—revealing cruelty even before he knows the beggar’s identity. Odysseus later kills him first during the slaughter in Book 22: “The arrow struck him in the throat… The cup fell from his hands as blood gushed forth.” His death symbolizes poetic justice; Antinous’ arrogance (“he had no thought of death”) meets the law of retribution that governs Homer’s moral order. ↩︎

- Eurymachus, in The Odyssey, is one of the chief suitors vying for Penelope’s hand—second only to Antinous in arrogance, but more manipulative and politically shrewd. He hides cruelty under a veneer of civility, often pretending to reason while plotting violence. When Antinous is slain, Eurymachus tries to save himself through rhetoric, claiming, “He was the ringleader; now he has paid,” and offering restitution of “twenty oxen each” (Book 22). Yet Odysseus rejects his plea, exposing hypocrisy as cowardice. Eurymachus’ death—“Odysseus shot him in the chest, near the nipple, and the arrow lodged in his liver”—completes the moral logic of the epic: clever deceit without honor is still folly. He represents persuasive corruption, undone when words finally lose their power against justice. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, the Muse is one of the nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory), divine patrons of the arts and inspiration.

She appears immediately in Book 1, when the poet opens the epic with the invocation: “Tell me about a complicated man. / Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost…”. This prayer-like appeal asks the Muse to inspire the storyteller, granting truth and eloquence to the song. ↩︎ - An Ithacan elder and seer (often glossed as “the only one to know both past and future”) who repeatedly counsels prudence and publicly reads omens in favor of Odysseus. At the first full assembly, when “Zeus sends two eagles that attack the faces of the men,” Halitherses stands up and interprets the sign as a prophecy of Odysseus’ imminent return—warning the suitors and their backers to desist. ↩︎

- n The Odyssey, Noëmon is a young Ithacan ship-owner, the son of Phronius, whose name—like his father’s—suggests wisdom or mindfulness. ↩︎

- Way-stations in Telemachus’ fact-finding mission: he visits Nestor in Pylos and Menelaus in Sparta and learns Odysseus still lives. Sparta is glossed as the Doric city of Menelaus. ↩︎

- Sea power and the poem’s divine antagonist; wrecks Odysseus’ raft after his men blind Polyphemus and hounds the nostos until the hero reaches Phaeacia and Ithaca. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Nestor is the wise, elderly king of Pylos, renowned for his hospitality, experience, and storytelling. When Telemachus visits him seeking news of Odysseus, Nestor warmly welcomes him and performs the duties of a gracious host — offering food, lodging, and guidance. ↩︎

- Agamemnon, in The Odyssey, is the king of Mycenae and brother of Menelaus, known as the commander of the Greek forces at Troy. His story serves as a tragic parallel to Odysseus’s. After returning victorious from the Trojan War, Agamemnon is murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Menelaus is the king of Sparta, brother of Agamemnon, and husband of Helen — whose abduction by Paris sparked the Trojan War. When Telemachus visits him, Menelaus is shown as a wealthy and somewhat boastful but generous host, mourning those lost in the war, especially Odysseus. ↩︎

- Aegisthus is depicted in The Odyssey as a treacherous usurper and adulterer, whose story serves as both moral warning and grim parallel to Odysseus’ situation. While King Agamemnon fought at Troy, Aegisthus—his cousin and rival claimant to the throne of Mycenae—seduced Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, seized power, and murdered the returning king despite divine warnings not to do so. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, pharmakon refers to a magical drug or potion used for healing, enchantment, or forgetfulness. The term appears most clearly in Book 4, when Helen mixes a pharmakon into the wine she serves to Menelaus and Telemachus. The drug, given to her in Egypt, has the power to erase pain and sorrow, making anyone who drinks it unable to weep — even if faced with death or loss. ↩︎

- (“The White Goddess”) — Sea divinity who saves Odysseus from Poseidon’s storm with a protective veil; emblem of sudden, place-bound aid. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Scheria is the mythical island of the Phaeacians, ruled by King Alcinous and Queen Arete. It is portrayed as a distant, almost divine place — peaceful, prosperous, and known for its seafaring skill and hospitality ↩︎

- Nausithous is described in The Odyssey as the former king of the Phaeacians, and the father of Alcinous and Rhexenor. According to the text, he was a son of Poseidon and Periboea, and it was he who led the Phaeacians away from their original home in Hyperia to the island of Scheria after they were harassed by the Cyclopes. There he founded their new civilization, building walls, homes, temples, and farmland—establishing the peaceful seafaring culture that would later aid Odysseus. ↩︎

- Alcinous is the king of the Phaeacians and the son of Nausithous, ruling over the island of Scheria. He is portrayed as a wise, generous, and god-fearing ruler, famous for his hospitality and justice. When Odysseus washes ashore after his long trials, Alcinous welcomes him warmly, offers food, gifts, and safe passage home—embodying the Greek ideal of xenia (sacred hospitality) ↩︎

- The Phaeacian princess who discovers the shipwrecked Odysseus on Scheria during a laundry outing; she gives him careful instructions on supplicating her mother, Queen Arete, and later reminds him he “owes [his] life” to her aid. ↩︎

- Demodocus is the blind bard of the Phaeacians, celebrated for his divine musical gift and storytelling prowess. King Alcinous calls him to sing at the royal feast in Book 8, describing him as a man “whom the Muse adored; she gave him two gifts, good and bad: she took his sight away, but gave sweet song”. ↩︎

- Hephaestus is the god of fire and metalworking, famed as a divine craftsman and inventor. In The Odyssey, he is the lame husband of Aphrodite, who traps her and Ares in an unbreakable net after discovering their affair, showcasing both his anger and cunning craftsmanship. ↩︎

- (Witch-goddess) — Enchantress of Aeaea who turns men into animals; after Hermes’ help, she becomes Odysseus’ host and mentor, sending him to consult Tiresias. ↩︎

- Troy is the great fortified city in Asia Minor where the legendary Trojan War took place — the central conflict that precedes the events of The Odyssey. The Greeks (Achaeans) besieged and destroyed it after ten years, using Odysseus’ cunning trick of the Wooden Horse to infiltrate and sack the city, slaughtering its people and ending the war. ↩︎

- Ismarus is a city in Thrace, home of the Cicones, whom Odysseus and his men attacked after leaving Troy. They sacked the city, killed the men, and took the women and treasures, but their greed led to a counterattack by the Cicones, resulting in heavy losses for Odysseus’ crew before they escaped by sea. ↩︎

- The Lotus-Eaters are a gentle, non-hostile people living on an island where the lotus plant grows, whose fruit causes forgetfulness and apathy in those who eat it. When Odysseus’ men taste the lotus, they lose all memory of home and desire only to remain there forever, prompting Odysseus to drag them back to the ships and tie them down to prevent further loss. ↩︎

- The Cyclopes are a race of one-eyed giants who live as solitary shepherds without laws, ships, or agriculture, each ruling his own cave without community or governance. Odysseus describes them as “lawless aggressors” and “without red-cheeked ships,” emphasizing their isolation and lack of civilization. The most famous of them, Polyphemus, son of Poseidon, captures and devours Odysseus’ men before being blinded by Odysseus’ cunning “No man” trick—a moment that reveals both their savagery and Odysseus’ wit. ↩︎

- Aeolus is the guardian and god of the winds, who lives on a floating island surrounded by bronze walls and is “well loved by all the deathless gods”. Zeus made him steward of the winds, able “to stop or rouse them as he wishes”; he gives Odysseus a bag of storm winds to speed his voyage, but when Odysseus’ men foolishly open it, the unleashed gales drive them back to Aeolus—who angrily refuses to help again, saying the gods must despise Odysseus. ↩︎

- Laestrygonia is a mythical land inhabited by the Laestrygonians, a race of giant cannibals who attack and devour Odysseus’ men, destroying all his ships except one. Their city, said to have been founded by Lamos, is marked by strange geography where day and night meet closely, symbolizing its eerie, inhuman nature. ↩︎

- Hades is the god of the underworld and ruler of the dead, whose gloomy realm lies “beneath the earth where sunlight never shines.” Odysseus must travel to the house of Hades and dread Persephone to seek prophecy from the dead seer Tiresias. ↩︎

- Persephone, the queen of the underworld and wife of Hades, is described as both dread and beautiful, governing over spirits and shadows. She “has given Tiresias alone full understanding, even now in death,” and later sends forth “the daughters and wives of warriors” to Odysseus during his visit among the dead. Together, Hades and Persephone embody the mystery and inevitability of death in The Odyssey. ↩︎

- Elpenor is one of Odysseus’ youngest and least wise crewmen, who dies accidentally after falling drunkenly from Circe’s roof. His spirit is the first shade Odysseus meets in the Underworld, where Elpenor pleads for proper burial rites so his soul may find peace; Odysseus later honors this by cremating him and raising a mound with his oar on top before sailing on. ↩︎

- In Homer’s The Odyssey, the Cimmerians are described as “a people living near the land of the dead”. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Sisyphus is briefly mentioned as a tormented soul in the Underworld, condemned to eternally roll a boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down each time he nears the top — a punishment for his deceitfulness and defiance of the gods. ↩︎

- In Homer’s Odyssey, the Sirens are mythical creatures whose enchanting song lures sailors to their doom. When Odysseus encounters them, he has his crew plug their ears with wax and binds himself to the mast so he can hear their beautiful yet deadly music without being drawn to destruction. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Scylla is depicted as a terrifying six-headed sea monster who lives beside the whirlpool Charybdis. When Odysseus’ ship passes through the narrow strait between them, Scylla snatches six of his men—one for each head—and devours them alive as they cry out in agony. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, Charybdis is described as a monstrous goddess in the form of a giant whirlpool that threatens to swallow passing ships whole. She resides near Scylla, the six-headed sea monster, and together they represent twin dangers for sailors navigating the narrow strait. ↩︎

- Eurylochus, in The Odyssey, is a self-assertive and cautious member of Odysseus’s crew. He often challenges Odysseus’s leadership—such as when he refuses to enter Circe’s hall, suspecting a trap, and later persuades the men to eat the sacred cattle of the Sun God, leading to their doom. ↩︎

- Calypso is the nymph who lives on the remote island of Ogygia and detains Odysseus for several years, offering him immortality if he stays with her. She represents temptation and the conflict between desire and duty in The Odyssey. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, the title “Earth-Shaker” refers to Poseidon, the god of the sea and earthquakes. The epithet highlights his immense power to cause natural upheavals—literally shaking the earth and the sea in his wrath. ↩︎

- In The Odyssey, the Naiads are nymphs of fresh water — divine spirits who dwell in streams, springs, and fountains. They are mentioned briefly as local deities associated with the natural world, often honored by mortals and gods alike. ↩︎