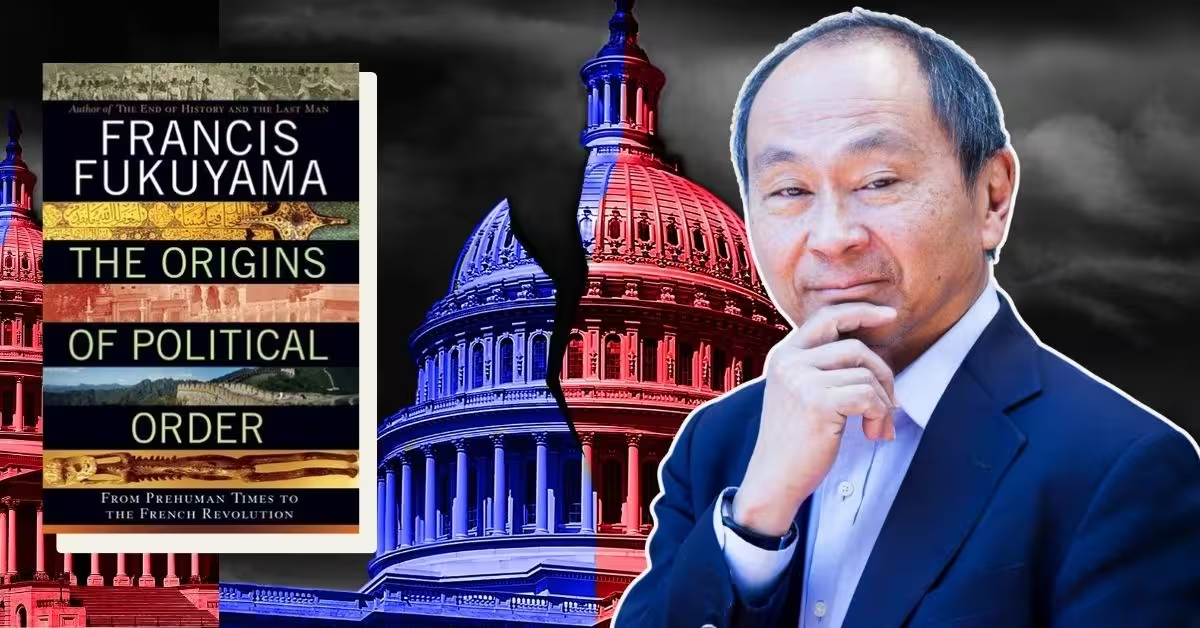

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (2011) is the first volume in a sweeping political history by American political scientist and economist Francis Fukuyama. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, this work builds a comprehensive framework for understanding how modern states, legal institutions, and political accountability emerged out of kinship-based tribalism.

Fukuyama, a senior fellow at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute and author of The End of History and the Last Man, commands attention not merely as a scholar but as a public intellectual. His academic training at Harvard under Samuel Huntington — to whom this volume is partly dedicated — and his work in global policy arenas position him as an authority who straddles both theory and application.

At the heart of Fukuyama’s work lies a deceptively simple question: How do societies transition from kin-based tribal orders to modern political states governed by law and accountable institutions? He argues that the origins of political order lie not in ideology or charisma but in the slow, contingent, and often painful emergence of three core institutional pillars: the state, the rule of law, and accountability.

Fukuyama notes with poignant clarity that “there is a virtue in looking across time and space in a comparative fashion. Some of the broader patterns of political development are simply not visible to those who focus too narrowly on specific subjects”.

Table of Contents

Background of The Origins of Political Order

Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (2011) is a monumental work in comparative political development. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the book ambitiously retraces the emergence of political institutions, examining the formative forces behind modern states, rule of law, and political accountability. Spanning regions as diverse as China, India, the Islamic world, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe, Fukuyama investigates why some nations have succeeded in building stable political orders while others have remained mired in conflict, corruption, or institutional stagnation.

This book is the first in a two-volume series, with the second volume titled Political Order and Political Decay (2014), which carries the analysis forward from the French Revolution to the 21st century. The unifying objective of the project is what Fukuyama metaphorically describes as the challenge of “getting to Denmark”—creating a society that is stable, democratic, prosperous, and governed by the rule of law.

According to Fukuyama, three key institutional pillars are essential to political development:

- The State – a centralized source of power capable of enforcing laws;

- Rule of Law – a system in which laws constrain political power;

- Accountable Government – rulers who are answerable to the governed.

He emphasizes that these pillars do not always evolve simultaneously or even in a linear fashion. For instance, China developed a strong state early on but lacked rule of law and accountability. Conversely, India maintained strong religious-based legal institutions but was slow to centralize state authority.

Fukuyama roots his analysis in both historical events and evolutionary anthropology, rejecting Enlightenment-era conceptions by Hobbes and Locke that postulate a rational “social contract” as the origin of the state. Instead, he argues that political order evolves from tribal organization rooted in kinship, driven forward by war, religion, and institutional competition.

What sets The Origins of Political Order apart is its scope. Fukuyama draws from multiple disciplines—political science, sociology, history, biology, and anthropology—to chart a long arc from the world of chimpanzee dominance hierarchies to the constitutional revolutions of Europe. The book is not only an ambitious scholarly enterprise but also a timely exploration of why modern state-building has repeatedly failed in post-conflict regions like Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Liberia.

2. SUMMARY

A Sweeping Arc from Primate to Parliament

This is not a history book in the traditional sense — it is an interdisciplinary inquiry. Fukuyama draws from evolutionary biology, anthropology, archaeology, sociology, theology, and political science to trace the arc of institutional development from tribal Melanesia to Confucian China, from Roman jurisprudence to European feudal assemblies.

Part: I- Before the State

Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order embarks on an ambitious intellectual quest: to trace the formation of political institutions from prehuman times to the eve of the French Revolution. In Part I: Before the State, Fukuyama challenges traditional political theory by pushing the origins of governance back beyond civilization, even before agriculture and written history.

He confronts thinkers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau with a kind of anthropological realism—grounded in biology, evolutionary psychology, and historical ethnography—that refuses to reduce politics to abstract axioms or social contracts. Instead, Fukuyama argues that political order is the product of evolution—cultural, institutional, and biological—not philosophical fiat.

The core assertion in Part I is that before the emergence of the modern state, human beings were organized through kinship—and that this early social form fundamentally shaped the development of political institutions. “The origins of political order,” Fukuyama writes, “lie in the human ability to form and sustain groups larger than the family”. Crucially, he argues that political institutions did not emerge in a vacuum but evolved from mechanisms embedded in human biology, such as reciprocal altruism and dominance hierarchies observed in primates.

Chapter 1: The Necessity of Politics

Fukuyama begins with a sobering claim: that politics is inescapable because it is embedded in our nature. Human beings are both social and competitive animals, “capable of cooperation on a large scale but also prone to violence and hierarchy”. The first chapter makes a clear case that the desire to transcend politics, so common in modern utopian ideologies, is naive. Political order, he writes, “is necessary because violence is always a possibility, and authority must be established to suppress it”.

Politics is not an artificial solution to human discontent, but a natural consequence of our biological and social evolution. Even our closest primate relatives engage in a form of “proto-politics”—dominance battles among male chimpanzees, for example, are resolved through strategic coalitions. “Politics among chimpanzees,” Fukuyama notes, “involves power, alliance formation, and betrayal—not unlike politics among humans”. This suggests that politics preceded the state by millennia and must be studied as a phenomenon shaped by natural selection.

Here, Fukuyama effectively dismantles reductionist theories of development, asserting that no single “turtle” lies at the base of human progress. Instead, political development is multi-dimensional, evolving along separate tracks of state-building, rule of law, and accountability—tracks that do not always converge.

Chapter 2: The State of Nature

In this chapter, Fukuyama critically engages with the Western philosophical tradition of the “state of nature,” especially the theories of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. While Hobbes imagined a brutish pre-political world marked by “the war of every man against every man,” Rousseau envisioned a more peaceful and innocent state, corrupted by civilization. Fukuyama challenges both by grounding his narrative in evolutionary science rather than abstract theorizing.

According to Hobbes, men submit to a Leviathan—a powerful state—in order to escape chaos. As Hobbes famously wrote, in the state of nature, life is “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short”. Locke, by contrast, sees the state as a protector of life, liberty, and property—but maintains that natural man is essentially rational and cooperative. Rousseau radically departs from this by insisting that “man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” suggesting that political society itself is a source of inequality and corruption.

Fukuyama’s response is cutting: “The fallacy of all liberal social contract theories,” he writes, “is the presupposition of a pre-social state of nature”. There never was such a state, he argues, because humans are social by biology. Evolutionary biology, he points out, demonstrates that human beings are born into groups, and political behavior evolves from kinship and reciprocity long before any contractual deliberation occurs.

Moreover, he uses primatology to illustrate that even apes form hierarchies and coalitions. This radically reframes our understanding of political order as an evolutionary adaptation, not a rational construct.

Chapter 3: The Tyranny of Cousins

In this powerfully titled chapter, Fukuyama explores the world of tribal societies—systems of governance based almost entirely on kinship ties, which he dubs the “tyranny of cousins.” In these systems, your rights, obligations, and status are determined by your familial position. Political relationships are personal, not institutional.

Fukuyama argues that tribalism is not a default state, but rather an adaptation that arose after the era of small family bands. Tribal societies flourished under specific ecological and technological conditions—particularly in post-agricultural contexts, where increased productivity required new forms of social organization. “Tribes were created at a particular historical juncture and are maintained on the basis of certain religious beliefs”.

This form of social organization could be both empowering and limiting. It provided social insurance and mutual aid, but it also constrained individuals through inherited obligations and a strong aversion to change or outsiders. The anthropological literature Fukuyama cites—especially on segmentary lineage systems—emphasizes that tribal societies often lack a central authority and instead operate through negotiated consensus and reciprocal sanctions.

Indeed, he cites how blood feuds in tribal societies operate much like deterrents in international relations: “Fear of incurring a blood-feud is… the most important legal sanction within a tribe and the main guarantee of an individual’s life and property”.

Chapter 4: Tribal Societies—Property, Justice, War

In this chapter, Fukuyama makes a vital pivot: he links kinship-based society to the development of private property, justice systems, and warfare. He contests Marxist and Rousseauian claims that property is a post-political invention. On the contrary, he writes, “the experience of communism strongly reinforced the contemporary emphasis on the importance of private property”.

In tribal societies, property is communal but not anarchic. Kin groups strictly regulate access and usage based on customary laws and ancestral ties. “Property rights in tribal societies are extremely well specified, even if that specification is not formal or legal”. He criticizes colonial administrators who imposed Western property norms on African societies without understanding the embeddedness of those rights in kinship and cosmology.

Tribal justice, as Fukuyama illustrates, lacks centralized enforcement. Instead, it resembles a decentralized form of diplomacy. Quoting Evans-Pritchard on the Nuer, he notes that “when a man feels that he has suffered an injury… he at once challenges the man who has wronged him to a duel and the challenge must be accepted”. This structure mimics the deterrent logic of Cold War geopolitics more than a modern legal system.

War, too, is fundamentally social. Tribal societies are organized for warfare not just to defend territory but to assert dominance. The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins famously described the tribal segmentary lineage as “an organization of predatory expansion”. Fukuyama argues that warfare catalyzed the rise of larger, more centralized organizations—the precursors to the state.

Chapter 5 — The Coming of the Leviathan

The final chapter of Part I, The Coming of the Leviathan, marks a profound transition—from kin-based tribalism to bureaucratized statehood. This chapter is the theoretical and historical apex of Fukuyama’s early argument: that the evolution of political order involved a radical break from tribalism, and this rupture did not happen evenly across societies. Instead, it was catalyzed by warfare, religion, and the consolidation of power under centralized, impersonal institutions.

To understand the Leviathan—a term borrowed from Hobbes—Fukuyama invites us to examine how states emerge from the ashes of tribal societies, through the imposition of authority that transcends familial bonds. “The essence of statehood,” he argues, “is the ability to exercise a monopoly of legitimate force over a defined territory”. But unlike Hobbes, who thought the Leviathan arose from a social contract, Fukuyama insists that states do not emerge through reasoned agreement, but rather through coercion, conquest, and necessity.

Kinship and Its Disruption

Central to Fukuyama’s argument is the idea that the first states broke the chains of kinship. In tribal societies, as seen in the previous chapters, kinship was the organizing principle of life. Your clan was your law, your government, and your social safety net. But this system had limits—it could not scale. Fukuyama writes: “States are organized on the basis of territory and not kinship; their most important feature is their impersonal administration”.

Thus, for the state to emerge, the tribal order had to be shattered. This happened most dramatically in ancient China, which Fukuyama identifies as the first modern state in history. He explains that during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770–221 B.C.), Chinese rulers dismantled lineage-based aristocratic power structures and replaced them with bureaucratic meritocracies, using legal systems, census data, and iron discipline.

This process was violent and far from democratic. The Chinese philosopher Han Fei, whose Legalist philosophy underpinned the Qin Dynasty, advocated for strict laws and harsh punishments to curb the excesses of familial favoritism. Fukuyama captures the radical nature of this shift: “The legalist solution was to break the power of entrenched aristocratic lineages by replacing them with officials selected on the basis of loyalty to the ruler”.

This historical example is critical to Fukuyama’s broader thesis—that political order did not emerge out of liberal intentions, but from authoritarian discipline. In fact, early state formation was more often driven by survival and efficiency than any notion of liberty.

Warfare as Catalyst

The second major theme of Chapter 5 is the instrumental role of warfare in forging states. Tribes, as we saw earlier, were often adept at small-scale conflict, but lacked the organization for prolonged or coordinated war. In contrast, states required standing armies, taxation, record-keeping, and central command—and warfare provided the crucible to develop them.

Fukuyama writes: “Warfare is the great consolidator of state authority… it forces societies to create institutions capable of mobilizing men and resources on a large scale”. The transformation is as functional as it is brutal. To survive, communities had to build centralized administrations—levying taxes, organizing logistics, suppressing local insurgents.

This phenomenon is observable across civilizations. In Mesopotamia, city-states like Ur and Lagash built walls and standing armies; in ancient Egypt, dynastic rulers established tax-collecting bureaucracies to fund pyramid-building and warfare. The need for military survival compelled a shift from personal rule to impersonal governance.

But again, Fukuyama departs from many modern liberal theorists here. He asserts that the state was not born to protect individual rights, but rather to win wars. Rights came much later.

The Role of Religion

A third essential factor in the transition to statehood, according to Fukuyama, is religion. Belief systems helped legitimize the authority of early rulers and sustain cohesion in diverse, non-kin populations. In the absence of shared bloodlines, shared gods became a unifying force.

“In tribal societies, religion and law are not separate spheres,” he observes, “but parts of a single social system”. As states formed, religious elites often buttressed secular power, whether through divine kingship in Egypt or the Mandate of Heaven in China. Fukuyama stresses that religion was not simply about belief—it was about social order.

This is a striking argument, and one with contemporary relevance. He implies that no state can rely purely on force; legitimacy is indispensable. And in premodern contexts, religion was often the only available ideology to provide this legitimacy. Even the most autocratic regimes needed divine sanction.

Why Some Societies Never Formed States

One of the more intellectually generous aspects of Fukuyama’s analysis is that he does not assume state formation was inevitable or uniform. In fact, he devotes a portion of Chapter 5 to exploring why some societies failed to make the leap.

He points to sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Pacific Islands as regions where kin-based tribalism persisted far longer, sometimes into modernity. Why? According to Fukuyama, “the absence of strong incentives to create a centralized authority—such as external threats or economic surpluses—left these societies in a state of arrested development”.

Ecological and geographic factors mattered. Societies that could support dense populations through agriculture (like in the Nile or Yellow River valleys) were more likely to centralize. Meanwhile, in regions of low population density and high mobility, the cost of creating a state often outweighed its benefits.

This helps explain the diversity of political outcomes across history. State-building is not an automatic endpoint of human society. It is a response to particular historical and environmental pressures, not an abstract ideal to be universally attained.

A Human Reader’s Reflection: Breaking Kinship, Building Order

Fukuyama’s portrayal of early state formation is both humbling and unsettling. It undermines romantic notions of an idyllic tribal past, as well as idealistic beliefs in the state as a guardian of liberty. Instead, the early Leviathan emerges as a necessary evil—a structure imposed upon kinship society not for justice, but for survival.

And yet, this transformation made everything else possible. The impersonal institutions of the state enabled commerce, infrastructure, literacy, taxation, and ultimately the rule of law—the next great evolution in political order, which Fukuyama explores in later parts.

By the end of Part I, we come to understand that political order is not a gift, but an achievement. It arises out of painful ruptures, forged in war, sustained by faith, and maintained by impersonal discipline. This view is a far cry from the Enlightenment idealism of Locke or Rousseau, and far more rooted in the raw, empirical reality of human history.

Part II: State Building in The Origins of Political Order

Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order is, at its heart, an archaeological excavation of the DNA of modern governance.

In Part II: State Building, the author journeys through the political histories of China, India, the Muslim world, and early Christian Europe, excavating the essential architecture of centralized authority. Fukuyama’s aim is not merely descriptive; it is philosophical, comparative, and ultimately normative. As he notes, “Modern institutions cannot simply be transferred to other societies without reference to existing rules and the political forces supporting them”. Nowhere is this insight more profound than in the section dedicated to the origins of the state, where Fukuyama dissects the complex, often fragile process of transitioning from tribalism to centralized rule.

The Chinese Model: Bureaucracy Before the West

The story begins, quite unexpectedly for many Western readers, not in Athens or Rome but in China. This is a deliberate and powerful choice. Fukuyama eschews the traditional Western-centric narrative and establishes China as the first society to develop a modern state in the Weberian sense—a centralized bureaucracy governed impersonally through merit rather than kinship.

In Chapter 6: Chinese Tribalism, Fukuyama explains that, much like other early human societies, China began with segmentary tribal lineages. The move toward centralized authority began with warfare and conquest, particularly under the Qin Dynasty. The Qin’s “legalist” political philosophy subordinated aristocratic and familial privilege to state authority, creating what Fukuyama calls the first true modern state—a government that maintained order across vast territory through a uniform bureaucratic apparatus.

“The Chinese developed a modern state in the Weberian sense more than two millennia ago,” Fukuyama writes, “without this being accompanied by either rule of law or democracy”. He points to the Han Dynasty’s consolidation of this model in Chapter 8: The Great Han System, where a massive and relatively meritocratic civil service emerged, powered by Confucian ideology. This shift was profound: impersonal administration replaced the patrimonialism that plagued other early states, laying the groundwork for centuries of relative internal stability.

What is emotionally compelling here is Fukuyama’s recognition of China’s paradox: the Chinese state was highly effective, yet it never truly embraced the political accountability or rule of law that would later define the liberal Western order. “A modern state without rule of law or accountability,” he cautions, “is capable of enormous despotism”. This caution haunts the remainder of Part II.

Chapter 9: Political Decay and the Fragility of Centralization

But China’s triumph was not eternal. Fukuyama devotes Chapter 9: Political Decay and the Return of Patrimonial Government to describing the process of regression, where centralized authority gives way to rent-seeking, nepotism, and what Max Weber called “patrimonialism.” Even in so-called “modern” states, personal connections and tribal loyalty resurface like deep tectonic faults.

“Political order is never permanently achieved,” Fukuyama reminds us. “Like biological systems, political institutions are prone to decay”. Here, he prefigures the modern development conundrum: it is not enough to build institutions; one must guard them vigilantly against erosion.

The Indian Detour: Religion as Obstruction

If China was a paragon of early state building, India was a powerful counter-example—what Fukuyama terms “The Indian Detour.” This detour was not a failure, but rather a divergence. While India transitioned from tribal to state-level societies around the same time as China, the rise of Brahmanic religion stifled the centralization of power.

In Chapter 10: The Indian Detour, Fukuyama narrates how religious doctrine—especially the codification of caste (varna and jati)—undermined the formation of an impersonal state. The Brahmans, in collusion with warrior castes, created a hierarchy that limited the king’s ability to tax, conscript, or govern freely. In stark contrast to China, where law and meritocracy supplanted kinship, India entrenched social stratification in metaphysical terms.

“In India, society was stronger than the state,” Fukuyama writes. “Political authority remained fragmented and constrained by caste and religious doctrine”. This difference cannot be overstated. Where China achieved vertical integration through bureaucracy, India remained horizontally segmented through caste. Political development was stunted by religious legitimacy that prioritized ritual over administrative capacity.

This is where Fukuyama’s political order theory shines with nuance. He does not merely lament India’s failure to build a centralized state; rather, he explores how political development is shaped—sometimes fatally—by ideological legitimacy. India’s intellectual tradition offered a powerful ethical framework, but one ill-suited to the needs of statecraft.

A Comparative Philosophy of State Building

Fukuyama’s treatment of these cases—China’s success, India’s detour—lays the groundwork for a more complex theory of political development, where state building, rule of law, and accountability are treated as distinct but interdependent variables. These three pillars do not necessarily evolve together. The Chinese state succeeded at governance but failed at liberty. The Indian society developed law and ethical sophistication but never consolidated coercive power.

The philosophical insight here is profound. Fukuyama moves beyond modernization theory—which assumes that political and economic development proceed hand-in-hand—and instead advocates for a more contingent, evolutionary model. Political institutions, like species, adapt (or fail) based on historical accidents, environmental constraints, and cultural inheritance.

“Human institutions are subject to deliberate design and choice… they are invested with intrinsic value… which makes them hard to change”. Thus, no linear path leads from tribalism to democracy. And no one-size-fits-all model of state building will ever work.

The Muslim World and Military Slavery

Francis Fukuyama’s chapter 13 “Slavery and the Muslim Exit from Tribalism” reveals one of the most original, emotionally charged, and intellectually provocative aspects of The Origins of Political Order.

The Muslim world’s confrontation with deeply entrenched tribal structures posed a significant obstacle to state formation. Fukuyama argues that the Islamic solution was not religious reform but institutional innovation—specifically, military slavery, a controversial but historically potent method of consolidating centralized political order.

“Military slavery was invented in the Arab Abbasid dynasty because the Abbasid rulers found they could not rely on tribally organized forces to hold on to their empire”.

This military-slavery system originated in the Abbasid Empire but found its most sophisticated expression in the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. The Mamluks, Turkic and Circassian slave soldiers, were deliberately cut off from tribal ties. Chosen for their strength and loyalty, they were indoctrinated into a military fraternity that ensured their allegiance lay solely with the sultan.

What makes this political order particularly striking is its one-generation rule: Mamluks could not pass their status onto their children. “The theory behind this was straightforward: a Muslim could not be a slave, and all of the Mamluks’ children were born Muslims”. Thus, the cycle of meritocratic recruitment persisted—at least temporarily.

However, as Fukuyama notes with human melancholy and political realism, even this radical system was not immune to decay. Over time, wealth, family ties, and patronage reasserted themselves. “The Mamluk system degenerated from a centralized state to something resembling a rent-seeking coalition of warlord factions”. This reflects one of Fukuyama’s central themes: political decay is endemic, even in apparently well-designed institutions.

The Ottomans: Controlling the Sword

The Ottoman Empire, which eventually defeated the Mamluks in 1517, presents the most successful model of Muslim state building. Like their Mamluk predecessors, the Ottomans also employed military slavery, but they innovated upon it in crucial ways.

Through the devshirme system, discussed in chapter 14 and 15, the Ottomans collected Christian boys from the Balkans, converted them to Islam, and trained them to serve in elite military units like the Janissaries. This system created a military caste that was simultaneously loyal to the sultan and divorced from tribal or familial allegiances:

“Unlike the Chinese bureaucracy, it was open only to foreigners… they developed a high degree of internal solidarity and could act as a cohesive group”.

The Ottomans maintained a clearer separation between military and civilian authority, avoiding the internal factionalism that had paralyzed the Mamluks. For nearly three centuries, the Ottoman state balanced centralized authority with internal administrative coherence. But, as Fukuyama so astutely observes, patrimonialism eventually returned even here, as the Janissaries grew into a hereditary and corrupt elite.

Their end came brutally: “In 1826, Sultan Mahmud II had the entire corps of Janissaries… killed by setting fire to their barracks”. Fukuyama uses this to illustrate how even the most durable state-building innovations can be undone by the inherent human impulse toward status inheritance and tribalism.

Western Europe: Christianity and the Birth of Rule of Law

While the Muslim world was pioneering state formation through military institutions, Western Europe was experiencing an entirely different revolution: the legal transformation of society through the Catholic Church. In Chapter 16: The Catholic Church Declares Independence, Fukuyama traces how Christianity, once a persecuted sect, evolved into an autonomous legal and institutional force that laid the groundwork for rule of law.

This began with the collapse of the Roman Empire and the separation of religious and political authority. The Church, in the absence of a strong state, “found itself a large property owner, running manors and overseeing the economic production of serfs throughout Europe”. In doing so, it had to evolve its own managerial bureaucracy, which would later serve as a model for emerging secular states.

The Church’s rejection of kinship-based inheritance—through celibacy rules, monastic life, and prohibitions on clerical marriage—further broke down tribal social organization, what Fukuyama evocatively calls the “tyranny of cousins”.

“European society was… individualistic at a very early point, in the sense that individuals and not their families or kin groups could make important decisions about marriage, property, and other personal issues”.

This early social individualism preceded state-building, a reversal of the sequence observed in China or the Islamic world. It fostered an environment in which the rule of law—not military coercion—became the primary mechanism of political order.

A Theory of Divergence

In bringing together these comparative examples, Fukuyama proposes a deeply human and politically astute theory: political development is not linear, but conditional. China built the first modern state but lacked rule of law. The Islamic world overcame tribalism through institutional ingenuity, yet succumbed to decay without external religious or legal constraints. Europe, in contrast, fragmented politically but developed strong legal institutions and social individualism—ironically through the power of the Catholic Church.

“It was not Christianity per se, but the specific institutional form that Western Christianity took, that determined its impact on later political development”.

This insight resonates deeply today as states grapple with balancing centralized power, legal order, and accountability. Political order is not simply a matter of having a strong state, but of having the right combination of state, law, and institutions rooted in human experience.

Fragmentation and Feudalism: The Western Puzzle

By the time we reach Chapter 17: The Reinvention of the State, Fukuyama’s tone shifts from comparative detachment to an almost elegiac fascination with the paradox of Western Europe’s political fragmentation. Unlike China’s centralized empire or the Ottomans’ disciplined military rule, Western Europe devolved into feudalism—a patchwork of lords, vassals, and monarchs with wildly uneven authority.

“Europe never returned to the high levels of political organization attained under the Roman Empire. Instead, it developed political institutions based on feudalism and manorialism”.

What may seem at first a political regression is, for Fukuyama, a historical precondition for the development of liberty. Feudalism, in all its chaos and decentralization, planted the seeds of pluralism—the idea that no one actor, not even the king, could fully dominate the political sphere. This unique check on power was less the product of conscious design and more the outcome of institutional deadlock.

In contrast to China’s “bad emperor problem”—where a centralized state, lacking accountability, becomes a tool of tyranny—Western Europe developed a balance of weakness. Kings were weak, but so too were barons, bishops, and burghers. Authority was always contested, always negotiated. Fukuyama notes:

“The weakness of European kings turned out to be a blessing in disguise. It forced them to negotiate with other social actors, creating early forms of representative government”.

Toward a Theory of Political Development

By the close of Part II, Fukuyama has laid out the groundwork for his theory of political development, rich in comparative depth and human complexity. His central thesis is this:

“Political order rests on three pillars: a strong and capable state, the rule of law, and mechanisms of accountability. These evolve through different sequences in different civilizations” .

China achieved statehood early but never developed constraints on centralized authority. The Muslim world innovated with military structures but fell victim to institutional decay. India had moral order without political capacity. Western Europe, through feudal entropy, accidentally cultivated freedom through fragmentation.

What makes this account feel so emotionally honest is Fukuyama’s refusal to prescribe a universal path. Political order is not a formula, but a living, breathing process, dependent on history, culture, and often tragedy. Fukuyama does not romanticize the West, nor denigrate non-Western trajectories. Rather, he asks a difficult, vital question:

“How can we create political institutions that are strong enough to govern effectively, yet constrained enough to protect individual rights?” .

This question, more than any other, animates the modern struggle for good governance. It is as relevant in today’s fragile democracies as it was in the feudal courts of England or the rice paddies of Qin China. The Origins of Political Order is, therefore, not just a book about history—it is a meditation on the human condition in politics.

“Order is not natural to human beings. It has to be created, and its maintenance is a perpetual struggle” .

In our own time, as democracies falter and autocracies rise, Fukuyama’s work is both a warning and a guide: state building is a fragile, noble endeavor, shaped by our deepest fears and highest hopes.

Part III: The Rule of Law

In Chapters 19 through 21, Fukuyama tracks the gradual emergence of accountable government—the third pillar of political development, alongside the state and rule of law. It’s not a story of revolution but of painful evolution.

The central mechanism here is the bargain: kings needed money—especially to wage war—and their subjects controlled it. In order to raise taxes, monarchs had to summon councils, diets, and parliaments. These forums became venues not just for negotiation but for institutional innovation.

“The state had to enter into a political bargain with elites, leading to the development of parliamentary institutions in England and elsewhere” .

Fukuyama’s most poignant example comes in England, where the Magna Carta (1215) represents not just a legal milestone but a constitutional rupture: “What began as an assertion of aristocratic privilege would, over the centuries, evolve into a broad concept of citizen rights and limited government” .

This process was deeply historical, layered with contradiction and compromise. In France, the crown suppressed noble power and built a centralized bureaucracy—stronger in the short term, but less pluralistic. In Germany and Italy, decentralization fragmented state capacity altogether. But in England, a tenuous balance was struck. Fukuyama traces this not to exceptionalism, but to contingent institutional interactions:

“The evolution of political institutions in Western Europe… was not driven by ideas or ideology, but by coalitional politics and bargains between kings and their subjects” .

Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order takes its deepest philosophical plunge in Part III, titled “The Rule of Law”, where he unpacks one of the most critical—and yet misunderstood—pillars of political modernity.

With intellectual breadth and surgical precision, Fukuyama does not merely recite the evolution of legal institutions; he explores the metaphysical and sociopolitical anatomy of what we term “rule of law.” Through the course of four chapters—17 to 21—he reconstructs the conditions that allowed this idea to transcend mere legality and evolve into a bedrock of modern governance.

In Fukuyama’s framework, the rule of law is not synonymous with laws or legislation. Rather, it is a body of abstract, normative rules—often rooted in religion or custom—that exist independent of and superior to the will of any ruler or government. He defines it as “a social consensus within a society that its laws are just and that they preexist and should constrain the behavior of whoever happens to be the ruler at a given time”.

This premise forms the intellectual keystone of Part III, and what follows is an exploration of how such a normative order became entrenched in European political development, particularly in contrast with India, the Islamic world, and China.

Chapter 17: The Origins of the Rule of Law

Fukuyama initiates the discussion by tracing the European exceptionalism in legal development. While other societies developed centralized political authority through military conquest or dynastic legitimacy, early European polities legitimized themselves through their capacity to dispense impartial justice. In England, for instance, the transition from customary law to royal law not only increased the prestige of the monarchy but also bolstered the legitimacy of the state. “It was the king’s ability to administer equal justice…that increased his prestige and authority”.

The English Common Law, built on a foundation of royal authority but administered through an evolving network of judges and common precedent, becomes Fukuyama’s exemplar of legal-political fusion.

Yet, he is not blind to the ideological underpinning of this shift. He draws heavily on Friedrich Hayek’s distinction between law and legislation, noting that the rule of law exists only where “the preexisting body of law is sovereign over legislation”. Thus, in this schema, law is not a tool of the state; it is a constraint on state power, and the state’s legitimacy stems from its deference to this constraint.

Fukuyama underscores this by referencing William Blackstone’s assertion that “no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to [natural law],” elevating the law above the legislature and affirming its transcendental nature.

Chapter 18: The Church Becomes a State

This chapter is arguably the intellectual epicenter of Part III. Fukuyama delves into the institutionalization of the Catholic Church as a quasi-state actor, particularly during and after the Investiture Conflict of the 11th and 12th centuries. In Europe, religious and secular authorities clashed not because they were always separate, but precisely because they were too intertwined.

Through the Gregorian Reform, the Church sought to emancipate itself from lay control, asserting its moral and institutional independence. This, ironically, laid the groundwork for secular rule of law. Fukuyama writes, “Religiously based laws constrained rulers only if religious authority was constituted independently of political authority”. In contrast, in societies like India and the Sunni Islamic world, where political and religious authorities remained fused or fragmented, rule of law did not develop institutionally.

The Catholic Church created a system of canon law, a bureaucratic hierarchy, and even a professional clerical class, all of which mirrored the secular state. It introduced principles like the officium vs. beneficium—distinguishing public office from private gain—a concept Max Weber later saw as foundational to modern bureaucracy. Hence, Fukuyama argues, “the Catholic Church was the first institution in Western history to be governed by a legal system that it had itself created, independent of secular rulers”.

This evolution endowed the Church with an authority above kings, capable of excommunication or moral censure, reinforcing a trans-political legitimacy that even monarchs feared to cross. It was precisely this supra-political legitimacy that became the seedbed of rule of law in Europe.

Chapter 19: The State Becomes a Church

In a philosophical reversal, Chapter 19 examines theocratic fusion in non-European civilizations. Fukuyama focuses especially on China, where religious institutions never matured into autonomous centers of authority. Ancestor worship and Confucianism were co-opted into state ideology, depriving China of any genuine source of “law above the emperor.” He writes, “religious authority never coalesced into a single, centralized bureaucratic institution outside the state”.

In the Islamic world, a similar problem occurred in reverse. While Islam provided a rich corpus of religious jurisprudence (sharia), the fragmentation of authority—between ulama, caliphs, and local rulers—prevented the institutionalization of a rule of law that could constrain sovereigns. Fukuyama’s verdict is precise: “Where religious institutions were either too weak or too captured by political authorities, the rule of law could not emerge.”

Thus, while in Europe the Church served as a counterbalance to royal power, elsewhere the absence of an institutionalized moral authority led to states that were, in effect, above the law.

Chapter 20: Oriental Despotism

Fukuyama turns next to a historical caricature—the idea of “Oriental Despotism”—and attempts to give it scholarly nuance. He focuses primarily on imperial China and its vast centralized bureaucracy, which was capable of impressive state control but lacked checks on arbitrary power. The state’s legalism was instrumental and administrative—not moral or normative.

Drawing from Confucian doctrine and administrative records, Fukuyama underscores that Chinese emperors were not bound by law in any true sense, even if their Confucian obligations urged them to rule justly. Hence, despite its bureaucratic efficiency, China’s imperial state failed to develop a legally pluralistic tradition like Europe’s.

What’s illuminating here is Fukuyama’s critique of modernity’s blind admiration for centralized efficiency. He argues that such systems often mask profound normative weakness: “What the Chinese lacked was not law per se, but law that could stand above the state and bind it.”

Chapter 21: Stationary Bandits

Concluding Part III, Fukuyama introduces Mancur Olson’s “stationary bandit” theory, wherein rulers settle down from looting to “governing” because long-term taxation is more profitable than short-term plunder. The bandit becomes a king, but his rule is still essentially predatory.

Fukuyama critiques Olson, noting that the rulers of agrarian societies often failed to extract taxes even at optimal rates. The absence of institutionalized accountability prevented even the self-interested logic of the “stationary bandit” from holding. In China, for example, “rulers simply did not exert themselves to correct [tax arrearage] problems,” pointing to deep political inertia rather than rational maximization.

Fukuyama’s subtle point is that the rule of law is not a byproduct of rational incentives alone. It requires institutional contestation, normative belief, and moral foundations—features conspicuously absent in societies where authority remained unchallenged and unaccountable.

To complete our exploration of Part III—“The Rule of Law”—in Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order, we must now address the intellectual ramifications of his comparative method and the broader implications for political development. This second half of our summary continues to build upon Fukuyama’s thesis: that the rule of law is not merely legal machinery, but a moral architecture that can legitimize authority, constrain power, and foster trust between rulers and the ruled.

Where Part III begins by defining the concept, it ends by evaluating its historical fragility and modern relevance. Fukuyama’s emphasis on the unique trajectory of Western Europe is not a Eurocentric boast, but a diagnostic tool for understanding why constitutionalism flourished in some regions and failed in others.

Why Europe, and Not Elsewhere?

Fukuyama’s argument ultimately pivots on the tripartite balance between the state, the rule of law, and accountability. He posits that only Europe succeeded in developing all three in mutually reinforcing ways—and this was due in large part to its historical fragmentation and ideological contestation.

In Europe, the Catholic Church served as a countervailing power to monarchs. It had its own courts, its own legal code (canon law), and its own bureaucracy. Most critically, it claimed universal moral authority, thereby constraining temporal rulers with spiritual legitimacy. This moral authority was not merely religious but deeply institutionalized. As Fukuyama notes:

“It was this independence of religious authority from political power that enabled the development of a law superior to political authority”.

In Islamic civilization, while sharia offered a theoretically perfect legal system, it lacked the bureaucratic autonomy and institutional independence that canon law acquired in Europe. Moreover, the ulama were fragmented, geographically dispersed, and often co-opted by local rulers. They did not possess an independent church-like structure capable of consistently restraining sovereigns.

In India, the Brahmanical tradition did create an elite class of legal-religious experts, but their authority remained divorced from state power. Kings ruled, and Brahmins advised or interpreted cosmic order—but rarely did the two realms overlap in a way that created systemic legal checks on governance. This resulted in a state that was “low capacity, low centralization, and low accountability,” as Fukuyama puts it.

And in China, the absence of an independent religious institution meant the emperor reigned supreme, unbound by any spiritual or moral authority above his own. “There was no Chinese equivalent of the Pope who could excommunicate an emperor,” Fukuyama observes. Legalism became instrumental rather than normative—a tool of governance, not a constraint upon it.

Hence, the rule of law, in the Fukuyaman sense, flourished only where religious authority was institutionally strong and organizationally autonomous, not fused or fragmented. In this respect, the Catholic Church was a singular phenomenon, creating the preconditions for legal modernity.

Legal Rationality vs. Political Rationality

What distinguishes Fukuyama’s narrative is his refusal to accept instrumental rationality—the kind associated with modern bureaucracies—as the only measure of legal development. He critiques the notion that legal systems are simply tools of statecraft or economic efficiency. Instead, he insists on a moral and normative criterion: laws must bind even the rulers, and they must be seen by society as just.

This is what separates the rule of law from rule by law. In the latter, laws exist to consolidate power. In the former, laws serve to limit it. Fukuyama thus aligns with theorists like Hayek, Blackstone, and even early Locke, all of whom viewed law as a transcendent authority.

Consider his citation of Blackstone once again:

“The principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature”.

This quote is no accident—it illustrates the natural law tradition underpinning early European legal thought, one which insisted that even kings were moral subjects to something beyond themselves. Fukuyama’s broader implication is chillingly relevant: where this moral architecture erodes, tyranny emerges beneath the veneer of legality.

The Bureaucratic Legacy of the Church

Another powerful insight from Part III is that the Catholic Church was, in many ways, the first modern bureaucracy. Long before state ministries formed, the Church had already established clerical education, record keeping, hierarchical appointment systems, and juridical oversight. This allowed it to project power and legitimacy beyond borders—and to offer a template for secular governments to emulate.

Fukuyama writes:

“The canon law of the Catholic Church was arguably the first modern legal system in Europe… This legal code set a precedent for legal rationality long before civil law was codified by monarchs or parliaments”.

This insight overturns popular assumptions that bureaucracy is a secular invention. In fact, the Church’s legal infrastructure outpaced the state’s, and when states eventually formed in Europe, they built on the Church’s innovations. This is why, in the West, law and governance matured in tandem—not in contradiction.

The Fragility of the Rule of Law

Despite his analytic clarity, Fukuyama is not triumphalist. He warns that the rule of law is historically fragile and easily subverted. Its survival depends on more than procedural systems; it requires social consensus, normative commitment, and institutional autonomy. In modern terms, this is a sobering reminder that even democracies are vulnerable to legal erosion if laws lose moral legitimacy or become politicized.

Moreover, the sequential development of institutions matters. Fukuyama cautions that premature democratization without prior establishment of the rule of law can lead to corruption and breakdown. This sequence—state → law → accountability—is not optional, he argues. In regions where this order is reversed, as in postcolonial states that democratized before building legal capacity, institutions often remain hollow.

He concludes:

“The sequence of political development matters. Institutions build upon one another, and missing foundations cannot easily be compensated for later”.

This insight frames the rule of law not just as a historical artifact, but as an ongoing project—one that remains precarious even in the 21st century.

In sum, Part III of The Origins of Political Order offers more than a historical narrative—it delivers a moral-political diagnosis. Fukuyama’s theory of the rule of law is rich, comparative, and deeply normative. It emphasizes that true legitimacy arises not from elections alone, nor from military strength, but from a shared belief in justice administered through independent institutions.

By dissecting the historical anomalies that gave rise to the rule of law in Europe—and by contrasting them with other civilizations—Fukuyama reminds us that political legitimacy cannot be manufactured overnight. It must be cultivated through institutions, disciplined by moral constraints, and legitimized by collective belief.

This is why the rule of law remains a cornerstone keyword in political development. It is not merely a matter of governance—it is the soul of constitutionalism, the foundation of trust, and the boundary between order and tyranny.

And perhaps most crucially, as Fukuyama subtly intimates, the rule of law is not guaranteed by history. It is preserved only by those who cherish its fragile architecture and defend its institutional integrity.

Part IV: Accountable Government

One of the most striking realizations when traversing the landscape of Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order is that political accountability—far from being the natural endpoint of political development—is a rare, fragile, and hard-won achievement.

In Part IV, aptly titled Accountable Government, Fukuyama takes the reader into a dense thicket of history where kings, nobles, bureaucrats, and peasants contend over the moral and institutional boundaries of state power. This is not a tale of linear progress or inevitable democratization, but a stark and often ironic meditation on how governance systems can fail precisely because they are trapped by their own past.

The keyword accountable government pulses throughout this section like a quiet moral drumbeat. Fukuyama defines it succinctly as a condition where “the rulers believe that they are responsible to the people they govern and put the people’s interests above their own”. But the devil is in the mechanisms. Accountability may emerge through moral traditions, such as Confucian paternalism, or through formal institutions—laws, parliaments, elections. The Western assumption that procedural democracy is the only legitimate path is challenged with clarity and emotional intelligence in this part of the book.

Chapter 22: The Rise of Political Accountability

Fukuyama begins the chapter with an intellectual warning shot: beware the seductive myth of “Whig history“—the retrospective illusion that liberal democracy was destiny. In reality, political development cannot be understood without comparisons across cultures and failures. “The lateness of European state-building,” he argues, “was the source of subsequent liberty”. This paradox—where weak kings ultimately laid the groundwork for democratic structures—is foundational to Fukuyama’s theory of accountable government.

There are, Fukuyama asserts, two types of accountability:

- Moral accountability, especially visible in Confucian traditions, where a king is educated from childhood to see himself as a steward of the people.

- Procedural accountability, which emerges from legal and constitutional limits on power, such as elections, rule of law, or legislative oversight.

In the West, especially in England, the early form of accountability was not democratic in the modern sense. Rather, it was a conservative defense of traditional law. “The most important law was the Common Law,” Fukuyama writes, “which was at that point heavily shaped by unelected judges”. Accountability in this period meant submitting the king to the moral and procedural limits of inherited institutions, not opening power to the masses.

What makes this chapter so emotionally and intellectually engaging is Fukuyama’s insistence that we understand accountability not just as a matter of electoral process, but of historical struggle. England, for instance, achieved a strange hybrid early on—parliaments that were oligarchic but still potent enough to challenge the Crown. This tension produced what he calls political solidarity—the essential social glue that holds rulers and ruled in a mutually binding contract.

One of the book’s most profound and chilling insights emerges here: authoritarian regimes can mimic accountability without embodying it.

Fukuyama offers the stark contrast between Hashemite Jordan and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq to illustrate the difference. Jordan’s monarchy, while not constrained by elections or a powerful legislature, still behaves with caution and care toward its constituents. Saddam’s regime, on the other hand, “served primarily the interests of the small clique of Saddam’s friends and relatives”. In this comparison, accountability becomes a question not just of systems, but of ethics and conscience—an insight few political theorists dare to underline.

This chapter is not merely historical exposition. It is, in many ways, a critique of our current assumptions. Fukuyama challenges liberal triumphalism and technological determinism. Democracy does not spring forth simply because a society becomes richer or more educated. Instead, accountable government must be cultivated—like an old and delicate tree whose roots must dig through centuries of soil hardened by privilege, hierarchy, and tradition.

Indeed, Fukuyama’s nuanced treatment of China stands as an example of how accountability can emerge without democratic forms. In Confucian cultures, kings were not held accountable by ballots, but by moral norms and the expectation of benevolence. While Western analysts might see such systems as inferior, Fukuyama insists on their validity in certain historical and cultural contexts.

What makes this analysis emotionally compelling is the recognition that accountability—like love or trust—is often invisible until betrayed. It is not a system so much as a felt presence, a quiet restraint that whispers “you are not above the rest.” Fukuyama reminds us that when this whisper vanishes, power begins to rot, regardless of the outer shell of law or election.

In short..

- Accountable government is not synonymous with democracy; it is broader, encompassing both moral and procedural dimensions.

- The English model of accountability arose not from popular demand but from legal tradition and elite bargaining.

- Fukuyama critiques “Whig history” as naive and misleading. Political accountability emerged not through inevitability, but contingency and struggle.

- Confucian traditions illustrate a non-Western model of moral accountability—power restrained not by law, but by ethical expectation.

- The early modern state often feared accountability, viewing it as a challenge to its legitimacy, not a prerequisite for it.

Chapter 23: Rente Seekers – The Anatomy of French Decline

If Chapter 22 presented the moral imperative of accountability in state governance, Chapter 23 throws us into a harrowing case study of what happens when that imperative is ignored. In “Rente Seekers,” Francis Fukuyama takes the reader into the slow decay of French monarchical institutions, exposing how the pathology of rent-seeking behavior—where elites use the state to extract wealth rather than serve the public—crippled France’s ability to evolve a truly accountable political system. The keyword accountable government once again frames this tragedy of missed opportunity.

This chapter is a raw dissection of institutional rot. Fukuyama shows how France, unlike England, failed to check its absolutist monarchy, not because of cultural backwardness but because of deliberate institutional choices. By the late 17th century, France had built an elaborate bureaucratic state—but not one that was genuinely public-oriented. Instead, it became a state of patrimonial privileges, where officeholders treated public posts as private property. “Virtually every office in the French bureaucracy, judiciary, and army could be bought and sold,” Fukuyama writes. “They passed from father to son like a house or estate”.

The Poison of Venality

The term venality of office may sound archaic, but its implications are horrifyingly modern. It was not simply that public servants were corrupt. It was that corruption was legalized, institutionalized, and valorized. A nobleman would pay a large sum to buy a judgeship or a treasury post—not to serve justice, but to guarantee lifelong income and immunity from scrutiny. The state itself became a marketplace of privilege. Fukuyama does not mince words: “The French state was a machine for the enrichment of its elites.”

This structure did not evolve by accident. French kings, perpetually in debt from wars and court extravagance, found in venal office sales a convenient cash flow mechanism. By doing so, they effectively sold off the legitimacy of the state for short-term financial relief. The system of accountability was inverted: rather than the ruler being accountable to the people, it was the people who were accountable to a parasitic elite.

Fukuyama reminds us that this isn’t just a story of poor governance. It’s a psychological tale of institutional betrayal. Citizens, increasingly aware of the entrenched inequality, grew alienated. “France had strong central institutions,” he explains, “but they were used to protect and serve the interests of the few”. In this environment, even reforms—when attempted—were seen with suspicion. Any move toward meritocracy threatened the entrenched beneficiaries of venality, and so reformers were often outmaneuvered or crushed.

England vs. France: A Study in Contrasts

Fukuyama masterfully juxtaposes this decay with England’s relatively more accountable trajectory. While England had its own share of corruption and elite capture, the balance of power between monarchy and parliament prevented the full-scale sale of government. “In England, the gentry had gained control of Parliament,” he writes, “and this allowed for the taxation and mobilization of resources without turning to the sale of offices”. England’s fiscal system, though imperfect, was more transparent, more flexible, and ultimately more legitimate.

This comparison is not merely academic. Fukuyama shows how fiscal capacity and political accountability are deeply intertwined. A state that cannot raise revenue efficiently without resorting to rent-seeking cannot develop modern administrative competence. And without fiscal legitimacy, even the most well-intentioned reforms collapse under the weight of elite resistance.

France’s story becomes a cautionary tale of how centralized power without accountability leads not to order, but to stagnation. Fukuyama notes that despite the Enlightenment bubbling within its intellectual class, France remained institutionally feudal. The paradox is chilling: the birthplace of liberté, égalité, fraternité was also the breeding ground of some of Europe’s most exclusionary governance structures.

The Psychological Dimension: Why It All Felt So Hopeless

Reading this chapter feels like watching a slow-motion train wreck. Fukuyama doesn’t just describe the system—he exposes its emotional toll. There’s a palpable sense of frustration that permeates the narrative, as if the French state was too intelligent to fail but too cynical to change. Beneath the cold bureaucratic description lies a tragic human truth: when citizens see no pathway for justice, revolution becomes inevitable.

Quoting Tocqueville, Fukuyama writes: “The French Revolution occurred not because the ancient régime was particularly repressive, but because it had tried—and failed—to reform.” This is a staggering insight. It suggests that half-hearted attempts at change, when done within a fundamentally unjust system, can actually accelerate its collapse. The people no longer tolerate injustice once they’ve tasted hope.

This isn’t merely history. Fukuyama warns that modern states can fall into the same trap. Systems of public office and governance, if designed for private benefit, will drain legitimacy, foster resentment, and eventually implode—whether in Bourbon France or contemporary kleptocracies.

Reflections on Accountable Government

Chapter 23 reinforces a central theme of Part IV: accountable government must be institutionalized. It cannot be outsourced to benevolent rulers or charismatic leaders. And most importantly, it must not be for sale.

- In France, the absence of a parliamentary counterbalance allowed monarchs to financialize the state.

- Venality hollowed out public institutions, transforming them into mechanisms for private gain.

- Efforts to reform the system were blocked by those who had already bought their place in it.

- This erosion of trust made popular uprising—i.e., the French Revolution—not only likely, but necessary.

In short..

- Venality of office in France created a deeply entrenched rent-seeking elite that undermined administrative efficiency and public legitimacy.

- Accountable government requires fiscal transparency and public trust—not just institutional control.

- England’s parliamentary taxation system allowed it to avoid the temptations of wholesale office sales.

- Attempts at reform in France failed because the political structure lacked both flexibility and legitimacy.

- The chapter warns of a broader truth: reform without accountability leads to instability, not renewal.

Chapter 25: Political Development and Political Decay

If the previous chapters of Part IV showed us how accountable government emerges—or fails to—in various civilizations, then Chapter 25 steps back to ask the ultimate question: Why do political systems decay, even after reaching success? In Fukuyama’s view, history is not a simple march forward. It is more like a spiral: sometimes progressing, often regressing, always susceptible to the erosion of institutional vitality. The idea of political decay isn’t new, but Fukuyama revitalizes it with fresh urgency, emotional intelligence, and global insight.

He begins with a provocative assertion: “Institutions are not static. They can grow stronger, but they can also weaken and decay over time”. This insight strikes at the heart of modern anxieties about democracy. We often assume that once a political system becomes stable, it will remain so. But Fukuyama warns: Accountable government is not a destination. It is a condition that must be continuously cultivated.

What Causes Political Decay?

Fukuyama identifies three major forces that cause political institutions to decay over time:

- Repatrimonialization – This occurs when state institutions that were once impersonal and rule-bound revert to personalistic, family-based control. It is a return to patrimonialism—where public office becomes a private fiefdom. This process, Fukuyama argues, is disturbingly common. “All bureaucracies are subject to capture by interest groups,” he writes. “The more stable the state, the more likely it is to be repatrimonialized”.

- Institutional Rigidity – Institutions that were once adaptive become too rigid to reform. This happens particularly in systems where powerful actors have embedded interests in the status quo. Fukuyama cites examples from the French monarchy, the Ottoman sultanate, and even modern America to show how vested elites often block necessary reforms. “Successful political development creates its own enemies,” he observes grimly.

- Cognitive Lock-in – Perhaps the most subtle, yet deeply human, form of decay. Societies become mentally locked into certain ideologies or institutional assumptions that blind them to changing realities. This form of decay is especially dangerous in high-performing societies, where past success breeds hubris.

The Eternal Struggle for Accountable Government

One of the most emotionally resonant themes in this chapter is the idea that accountable government is always under siege. It is not a natural condition but a historical anomaly. Fukuyama draws on the example of India, where colonial institutions created a legal-rational framework, but post-colonial repatrimonialization quickly undermined it. Civil service appointments, once merit-based, became tools of political patronage.

Meanwhile, in modern democracies, he sees alarming signs of decay: polarization, media manipulation, interest-group capture. “Even well-designed institutions can decay if the people inside them cease to believe in their legitimacy,” he cautions.

There’s something deeply human in this warning. Political institutions, like marriages or friendships, are not maintained by structure alone. They are maintained by belief—a shared emotional and moral investment that binds people to something larger than themselves.

Is There Hope?

Yes, but it is conditional. Fukuyama does not end on a note of despair. Instead, he calls for vigilance. Political development must be seen as a constant negotiation between order and adaptability. States must balance three pillars:

- The State – capacity for centralized governance and enforcement.

- Rule of Law – binding constraints on power, applicable to all.

- Accountable Government – formal or moral mechanisms by which rulers are answerable to the ruled.

Each of these pillars must evolve, sometimes at different speeds. Too much state, and you get autocracy. Too much law, and you get paralysis. Too much accountability without capacity, and you get populist dysfunction.

Fukuyama leaves us with a kind of philosophical roadmap—not of answers, but of questions we must never stop asking. Is our government still responsive? Are our institutions resilient? Have our elites grown detached from the public good?

This part of Fukuyama’s magnum opus is a profound meditation on the fragility and beauty of political accountability. Whether in medieval England, revolutionary France, Ottoman Turkey, or imperial Russia, the lesson is the same: power must be restrained not only by law but by conscience. Institutions alone are not enough. It is the human spirit—civic virtue, public morality, and historical awareness—that keeps accountable government alive.

Part V: Toward a Theory of Political Development

In Part V of The Origins of Political Order, titled Toward a Theory of Political Development, Francis Fukuyama culminates his intellectual journey through millennia of political evolution by tackling two fundamental themes: the mechanisms of political development and the roots of political decay. This is not merely a theoretical endeavor. It is, in essence, Fukuyama’s attempt to reclaim the analytical richness of 19th-century historical sociology while challenging both the triumphalist tones of classical modernization theory and the deterministic bent of Marxist historiography.

We begin, as Fukuyama does, with the biological roots of politics—and we end with a reappraisal of how modern complexity reframes the conditions for durable political order.

Chapter 29: Political Development and Political Decay

The Biological Foundations of Politics

Fukuyama roots his theory in a deep anthropological understanding of political life. Political institutions, he asserts, do not simply emerge from abstract social contracts or rational deliberation. Rather, they grow out of natural tendencies toward kin selection, reciprocal altruism, norm-following, and the quest for intersubjective recognition (the capacity to acknowledge and appreciate the subjectivity of another individual). These tendencies—anchored in evolutionary psychology—form the “natural building blocks” of political behavior.

He writes, “Inclusive fitness, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism are default modes of sociability. All human beings gravitate toward the favoring of kin and friends with whom they have exchanged favors unless strongly incentivized to do otherwise”. This principle undergirds the persistence of patrimonialism and clientelism in both ancient and modern states.

In other words, political development requires overcoming these default tendencies. But this is not a linear or inevitable process. It is hard-won, always vulnerable to decay, and often contingent on specific historical or even violent circumstances.

Defining Political Institutions

Fukuyama relies on a classical Weberian definition of political institutions as “stable, valued, recurring patterns of behavior.” He is also informed by Douglass North’s concept of institutions as “humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction”. Yet he critiques North for failing to distinguish adequately between formal and informal institutions, and for not offering sufficient criteria to measure the degree of institutionalization—such as autonomy, complexity, and adaptability.

In this context, political development is the process by which societies construct effective institutions that serve three essential functions: the creation of a modern state, the maintenance of the rule of law, and the establishment of accountability. These three pillars are not necessarily co-evolutionary.

Political Decay: The Twin Mechanisms

Where institutions fail to adapt, they decay. Fukuyama identifies two principal mechanisms of political decay:

- Inertia and Maladaptation: Institutions are created to solve specific challenges in particular historical contexts. Once those challenges fade or evolve, the institutions often fail to follow suit. “The disjunction in rates of change between institutions and the external environment… accounts for political decay or deinstitutionalization”.

- Repatrimonialization: Even advanced bureaucracies can regress into clientelist and nepotistic structures. The “default manner of human interaction,” Fukuyama reminds us, is the exchange of favors among kin and friends. This form of political decay is insidious precisely because it mimics natural human sociability. “There is constant pressure to repatrimonialize the system,” he writes.

This perspective gives new meaning to modern political dysfunction. From congressional gridlock in the U.S. to state capture in post-colonial regimes, Fukuyama’s diagnosis suggests that these are not anomalies but rather expected regressions in the long struggle for political institutionalization.

Violence as a Catalyst

It is in this chapter that Fukuyama makes one of his most provocative claims: that violence often becomes a necessary, if tragic, catalyst for institutional reform. “Sometimes violence is the only way to displace entrenched stakeholders who are blocking institutional change”. The decimation of aristocracies in China through warfare, or the emancipation of U.S. slaves through civil war, are cases in point.

One cannot help but read this with a cold shiver of historical recognition. In a world committed to peaceful reform, the enduring truth is that entrenched elites rarely cede power voluntarily.

Chapter 30: Political Development, Then and Now

In Chapter 30, Fukuyama turns his lens on modernity. He begins with a critique of classical modernization theory—the belief that economic, political, and social progress come bundled as part of a unified process. That theory, he notes, was shaped by thinkers like Marx, Weber, and Durkheim, who believed that capitalist markets, individualism, urbanization, and democracy would advance hand in hand.

“Modernization was of one piece,” Fukuyama summarizes, “it included development of a capitalist market economy… emergence of strong, centralized, bureaucratic states… and the transition from communal to individualistic social relationships”.

But history, he argues, has confounded these assumptions. The Chinese state, for example, developed a modern bureaucracy over two thousand years ago—long before it had anything resembling rule of law or democracy. Conversely, India had deep traditions of law and accountability, but a weak state apparatus.

This is the crux of Fukuyama’s theory: the pillars of political development do not evolve in lockstep.

The Huntingtonian Legacy

Fukuyama pays intellectual homage to his mentor, Samuel Huntington, whose Political Order in Changing Societies had warned that premature democratization could destabilize fragile political systems. “Democracy, in particular, was not always conducive to political stability,” Fukuyama echoes.

This insight reemerges in Fukuyama’s own work through the lens of the “authoritarian transition,” in which countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and Indonesia prioritized state-building and economic growth under autocratic regimes before liberalizing politically.

Fukuyama does not necessarily advocate authoritarianism. Rather, he insists that sequencing matters. Without first building an effective state, democratization can unleash instability rather than usher in liberty.

The Interplay of Developmental Dimensions

The chapter then dives into the intricate interactions among economic, social, and political development:

- Economic Growth and the Rule of Law: Property rights and contract enforcement foster growth, but these need not be universally applied. “Stable property rights exist only for certain elites… and this is sufficient to produce growth for at least certain periods of time”.

- Democracy and Economic Growth: The correlation, Fukuyama suggests, is complex. While democratic systems may consolidate at higher levels of income, authoritarian regimes have often overseen impressive economic booms.

- Civil Society and Democracy: Social mobilization is a double-edged sword. It can strengthen democracy—or, as in Bolivia and Ecuador, destabilize it when political institutions are too weak to accommodate newly empowered groups.

- Ideas and Legitimacy: Perhaps most profoundly, Fukuyama reminds us that legitimacy is shaped by ideas, not merely institutions. The collapse of communism, for instance, was as much a crisis of belief as of bureaucracy.

From Theory to Praxis: Why Political Development Still Matters

Fukuyama closes Part V with an uncomfortable truth: political development is not a one-way street. States can and do regress. And ironically, the very institutions that once guaranteed political stability can become obstacles to reform. In his words, “Political systems are much more subject to decay than we realize”.

This insight is deeply relevant for mature democracies like the United States. Fukuyama’s diagnosis of repatrimonialization—that is, the re-infiltration of nepotism, rent-seeking, and clientelism into what were once meritocratic institutions—feels unnervingly prescient. When he writes that “political decay occurs when institutions fail to adjust to new social realities”, one hears echoes of present-day debates about gerrymandering, dark money in politics, and administrative gridlock.

Fukuyama’s caution is that democracy and constitutionalism alone are insufficient. Without a robust and adaptable bureaucracy—what he calls a “modern state”—governance decays. And once decayed, restoring institutional integrity becomes exponentially harder.

The Myth of Institutional Transferability

One of the most intellectually provocative claims in Chapter 30 is Fukuyama’s challenge to the assumption that political institutions can be easily transplanted across cultures and geographies. The belief that liberal democracy can be exported—via aid, occupation, or NGOs—is, in his view, a dangerous delusion.

“Institutions that arise spontaneously out of local conditions,” he asserts, “tend to be far more effective and legitimate than those imported wholesale”. This is not a call for cultural relativism but rather for contextual humility.